The Wehrmacht in Alsace was starved of forces due to the shift of resources to the Ardennes in November and December 1944. As a result, Heeresgruppen G and Oberrhein both had to make do with badly depleted infantry divisions and a minimum of Panzer formations. These units were reinforced by a motley selection of improvised units including various march battalions, police, and Volksturm units.

Germany’s precarious manpower situation in 1944 led to the creation of Volksgrenadier divisions as an alternative to conventional infantry divisions. The new organization was intended to offer maximum firepower with minimum personnel and equipment. They were intended primarily for defensive missions on elongated fronts, and were not optimized for offensive missions due to inadequate mobile resources and a stripped-down organizational structure. Of the 173 infantry divisions nominally in the Wehrmacht order of battle in January 1945, 51 were Volksgrenadier divisions. In the case of Alsace, AOK 1 was composed primarily of Volksgrenadier divisions with six of the seven infantry divisions in this configuration. The opposite was the case with AOK 19, with only one of its eight infantry divisions in this form.

The Festung Kommandant Oberrhein was responsible for constructing the Vogesenstellung fortification line in the High Vosges, starting in September 1944. This surplus Panther tank turret was being emplaced in the defense line in the Saales Pass but was overrun by the Seventh Army in late November before it was completed. (NARA)

Another type of defense work being installed in the Vogesenstellung near Saales was the Krab Panzernest. Several can be seen here ready for installation in their transport configuration. These prefabricated machine-gun pillboxes consisted of an armored cupola that was towed into position upside down; the draw-bar for towing the assembly is attached to the machine-gun embrasure. After a suitable trench was dug, the pillbox would be rotated into the upright position, and dropped into place. This particular type of fortification was widely used by the Wehrmacht in France, Germany, Italy, and the Eastern Front as a means to quickly establish a fortified defense when there was neither the time nor resources to create concrete pillboxes. The Vosges defenses had 50 of these delivered for installation. (NARA)

Casualties in 1944 had far outstripped the ability of the Wehrmacht to make up for losses with trained personnel. The Wehrmacht typically allowed infantry divisions to be burned out in combat, and when they had lost the majority of their infantrymen, the division would be hastily rebuilt with raw recruits and then sent back into the line without proper tactical training. The principal manpower resource in late 1944 was the large number of surplus Luftwaffe ground crews and Kriegsmarine personnel since so many aircraft and warships were derelict due to a lack of fuel. Although the morale and capabilities of these young troops were often quite good, they were usually sent into battle with only the most rudimentary sort of infantry training. An additional source of cannon fodder came from men who were combed out of industry after having been given exemptions earlier in the war; they were usually older and less fit than the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine transfers.

A typical example in Alsace was the 256. Volksgrenadier-Division in the Bitche sector. The original 256. Infanterie-Division was annihilated in the July 1944 Red Army offensive. As was often the case, a small cadre of headquarters, support troops, and artillerymen survived the division’s destruction, leaving a “shadow division” which could serve as a kernel from which to grow a new division. It was reformed in Saxony in September 1944 by combining the Eastern Front survivors with elements of the newly created but incomplete 568. Volksgrenadier-Division. The majority of the new recruits in the division came from industrial, economic, and administrative posts in Germany who had previously been exempted from service, and the divisional commander complained that they were too old and lacked the endurance needed for infantry combat. The rest came mainly from Kriegsmarine personnel who were “young, healthy and strong men of high morale … who later constituted the backbone of the infantry regiments particularly because of their untapped physical and emotional resources.” With virtually no individual training or unit tactical training, the division was rushed to the Netherlands at the end of September and committed to the fighting along the Scheldt estuary against British and Canadian troops at the beginning of October. The divisional commander noted that only one of the three regimental commanders had command experience; the battalion commanders were eager for action but young and inexperienced. After a month of fighting, the division was pulled out and sent to the Hagenau sector in Alsace against US forces, where it was again bled white. By the time of Operation Nordwind at the beginning of 1945, the rifle companies were down to only 40 percent of their strength, and in the opinion of their divisional commander, only fit for defense. As was typically the case, the other elements of the division were in somewhat better strength with the engineers at about 70 percent strength and the artillery at about 90 percent strength. Its Panzerjäger (tank destroyer) battalion had only three assault guns instead of the authorized 14 and only eight towed 75mm antitank guns. The signals units were weakened by the need to divert divisional troops to the rifle units to make up for combat casualties, and the radio units were only marginally capable of conducting their tasks in combat due to a lack of training. The divisional commander concluded that the unit was “decisively impaired” and needed at least two weeks out of the line for rebuilding; instead, it was assigned an offensive mission in harsh winter conditions. The only reinforcements received were a “march battalion” of about 250 poorly trained replacements. There was a general shortage of winter clothing and waterproof boots, and heavy infantry weapons were in short supply, especially mortars and heavy machine guns.

Panzer support in Alsace was weak, since so many units had been shipped to the Ardennes sector. The only mechanized unit earmarked for the initial Nordwind attack was 17. SS-Panzergrenadier-Division “Götz von Berlichingen,” a formation that had been in continual combat with the US Army since Normandy, and which had been burnt out and rebuilt on several occasions. The neighboring army commanders felt that its main problem was poor leadership, and it had lost several divisional commanders and numerous junior commanders during the autumn. The field army staff labeled the current commander as incompetent. Its main armored element, SS-Panzer-Abteilung 17 Bataillon was equipped mostly with assault guns instead of tanks, with 45 StuG III assault guns, three PzKpfw III command tanks, six Flakpanzer 38(t) vehicles, and four Flakpanzer IV Wirbelwinds on hand, of which 84 percent were operational. The SS-Panzerjäger-Abteilung 17 Bataillon was similarly equipped with 31 StuG III assault guns, two Jagdpanzer IVs, one Marder III and eight towed 75mm PaK 40 anti-tank guns; only 67 percent of the vehicles were operational with many of the old StuG III assault guns being worn out or damaged in combat. Their strength was later increased by 57 assault guns that arrived after Christmas, but the reinforcements had been sitting out in the open for months and only a few could be rendered serviceable before the attack. The division’s two Panzergrenadier regiments were burned out and at less than half strength in the middle of December, but some additional troops were received in the last week before the offensive, mainly of “an inferior type” of German (ethnic Germans from eastern Europe). Senior officers at AOK 1 were so unimpressed by the poor performance of the 17. SS-Panzergrenadier-Division in the autumn fighting that they wanted to strip it of its assault guns to re-equip the 21. Panzer-Division, but Berlin refused.

The two other mechanized formations earmarked for Nordwind were the 21. Panzer-Division and the 25. Panzergrenadier-Division, both of which were placed in army reserve and not committed during the initial fighting. The 21. Panzer-Division had been badly beaten up in the autumn fighting, but was rebuilt in late December. Panzer-Regiment 22 was re-equipped and had a full tank strength of 38 Panthers and 34 PzKpfw IV tanks, but only four of its authorized 21 Jagdpanzer IV tank destroyers. It was particularly weak in armored infantry half-tracks having no light SdKfz 250s and only 29 of the 57 authorized SdKfz 251 troop-carrying half-tracks. It had to make do with civilian trucks. Manpower strength in the Panzergrenadier regiments was fair: Panzergrenadier-Regiment 125 was at 70 percent strength and Panzergrenadier-Regiment 192 was at 56 percent strength. The 25. Panzergrenadier-Division was not fully pulled out of the line until Christmas Eve and its rebuilding was less extensive. Panzer-Abteilung 5 had only six Panthers, five Jagdpanzer IV tank destroyers, and 3 Möbelwagen Flakpanzers; which was only 23 percent of its authorized strength. Its Panzerjäger-Abteilung 25 was in only marginally better shape with 14 StuG III assault guns, at 33 percent of authorized strength. Its two Panzergrenadier regiments were in better shape so far as infantry halftracks were concerned with 131 SdKfz 251s on hand, or 82 percent of authorized strength; manpower in the two regiments had been reduced to barely a quarter of their full strength early in the month and both regiments were hastily filled to partial strength by early January.

Artillerie-Stab 485 was the artillery arm of Wehrkreis V, responsible for Alsace. It raised a number of fortress artillery battalions for Festung Kommandant Oberrhein using captured heavy artillery like this 203mm Haubitze 503/5(r), the Soviet B-4 203mm Howitzer M.1931. This particular howitzer was deployed near Sarrebourg for the defense of the Low Vosges under an elaborate camouflage cover which has mostly been stripped away in this view after the battery was overrun by the Seventh Army in late November 1944. (NARA)

Since so much of the Panzer strength was being held in reserve, the attacking infantry had to depend on supporting assault guns, with about 80 in AOK 1. The schwere-Panzerjäger-Abteilung 653 (Heavy Tank Destroyer Battalion 653) was equipped with the monstrous Jagdtiger, which proved virtually useless because of its poor mechanical reliability. At the beginning of Nordwind, only two vehicles were at the front due to numerous breakdowns during transit. A few more arrived during the fighting and were attached to the 17. SS-Panzergrenadier-Division. Two flame-thrower tank companies, Panzer-Flamm-Kompanien 352 and 353, were attached to Heeresgruppe G due to the presence of so many Maginot Line bunkers in this sector. There was also a single Jagdpanzer 38(t) tank destroyer battalion under Heeresgruppe G, Panzerjäger-Abteilung 741, committed during Operation Nordwind. Besides these separate Panzer units, a very modest number of assault guns were organic to the infantry divisions.

Due to the significant number of Maginot Line fortifications in the battle-zone, AOK 1 was allotted two companies of flame-thrower tanks, equipped with the new Flammpanzer 38(t), a version of the better-known Jagdpanzer 38(t) Hetzer assault gun. This one from Flammpanzer Kompanie.353 was captured while supporting the attacks of the 17. SS-Panzergrenadier-Division near Gros-Réderching against the American 44th Division. (NARA)

The AOK 1 had an attached Volks Artillery Gruppe with a pair of Volks Artillerie Korps and two artillery rocket brigades. While the presence of two artillery corps may seem impressive, in reality these so-called “corps” were in fact reinforced regiments consisting of five medium and heavy artillery batteries and a single heavy anti-tank battery with 88mm guns. The Volks-Werfer brigades had been created in mid-December 1944 and each consisted of two regiments with a total of 18 batteries and 108 210mm multi-barrel Nebelwerfer rocket launchers. The army-level artillery support was divided between the two main attacks. The Luftwaffe’s 9. Flak-Division was in the area and was ordered by Berlin to cooperate, but it was barely able to provide anti-aircraft cover for the massing of forces and it had only a limited capability to provide some additional artillery support during the offensive itself.

The new Panzergrenadier divisions were supposed to be allotted a company of 14 assault guns for organic armored support. One of the more common types in Alsace was the Jagdpanzer 38(t), popularly called the Hetzer, which was a low-cost expedient in place of the older and more durable StuG III. This particular example in Oberhoffen on February 13, 1945 is being examined by a GI from F/142nd Infantry, 36th Division and was probably from Kampfgruppe Luttichau, which fought in the Gambsheim bridgehead. (NARA)

Beyond the principal tactical units, the Wehrmacht in Alsace also had to make do with a remarkably motley assortment of rear-area units that were often rushed into defensive positions to plug gaps. Due to the proximity to the Westwall there were a variety of fortress infantry and fortress artillery units that could be cannibalized for platoons and companies. Besides combat units under tactical command, the Wehrmacht also had rear-area organizations within Germany to manage the recruitment and training of new units such as the Ersatzheer. Wehrkreis V, headquartered in Stuttgart, managed the creation of replacement units with the administrative Division 405 in Alsace. Besides these training units, there were rear area field commands to manage local security including military police, and the Landes Schützen units which were regional defense units made up of 45–60-year-old men. Feldkommandant 987 was responsible for the district behind AOK 1, and besides security it was also responsible for organizing rear-area non-combatant troops into “alarm units” which, in theory, could be called up in the event of emergency. In addition to the field commands, major cities had their own Wehrmacht Kommandant with defensive responsibilities in time of emergency. In practice, these rear area commands had little defensive value as their modest security forces and military police were pilfered by the tactical commands before the arrival of Allied units, leaving them with only a minimum of military police, unarmed administrative personnel, local construction troops, and fixed flak batteries.

The local defense forces were supposed to be supplemented by Volksturm units. The Volksturm was a pet project of propaganda minister Goebbels to create a Nazi-party militia with enough political fervor to overcome the lack of training and weapons. While the Volksturm showed some promise in eastern Germany, its performance in western Germany was pathetic. The Volksturm concept was generally opposed by the regular army as a waste of weapons. Since the local population had already been thoroughly combed for troops, the Volksturm was recruited either from boys too young for conscription, or old men who the army felt had little use in uniform even in the marginally useful Landes Schützen battalions. The Volksturm also tended to undermine local civil defense efforts, which had come to depend on this same source of manpower to deal with local emergencies. As an example, a Volksturm battalion raised in Freiburg and dispatched to the front in Alsace had to be recalled to Freiburg in the aftermath of an RAF raid on the city. To further sour the army on the whole idea, the Volksturm were under the command of local political authorities, the local Kreisleiter, which made them even less useful in defense.

These prisoners captured by the 143rd Infantry, 36th Division in Rohrwiller on February 4, 1945 were fairly typical of German infantry in Alsace, all former members of the Luftwaffe who had been transferred to the army in the autumn of 1944 after so many Luftwaffe squadrons were grounded by a lack of fuel. (NARA)

| OPERATION NORDWIND (JANUARY 1, 1945) | ||

| UNIT | COMMANDER | HEERSGRUPPE G ASSESSMENT |

| Heeresgruppe G | Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz | |

| 1. Armee | Generalleutnant Hans von Obstfelder | |

| 25. Panzergrenadier-Division | Oberst Arnold Burmeister | Weakened by recent combat, and equivalent to reinforced regiment in infantry strength |

| 21. Panzer-Division | Generalleutnant Edgar Feuchtinger | Battle-weary but could still field a regimental Kampfgruppe in mobile role |

| 6. SS-Gebirgs-Division “Nord” | SS-Gruppenführer Karl Brenner | Excellent but not yet fully in theater |

| Sturmgruppe I | ||

| XIII SS-Infanterie Korps | Obergruppenführer-SS Max Simon | |

| 19. Volksgrenadier-Division | Generalleutnant Walter Wißmath | Battle-weary |

| 36. Volksgrenadier-Division | Generalmajor Helmut Kleikamp | Combat strength equivalent to an infantry regiment, morale good |

| 17. SS-Panzergrenadier-Division | SS-Standartenführer Hans Lingner | Strongest division in army group but its achievements failed to match its strength |

| Sturmgruppe II | ||

| XC Infanterie Korps | General der Flieger Erich Petersen | |

| 559. Volksgrenadier-Division | Generalleutnant Kurt Freiherr von Mühlen | Battle-weary |

| 257. Volksgrenadier-Division | Generalmajor Erich Seidel | Full strength but incomplete training |

| LXXXIX Armee Korps | General der Infanterie Gustav Höhne | |

| 361. Volksgrenadier-Division | Generalmajor Alfred Philippi | Combat strength equal to about two regiments, good morale |

| 245. Infanterie-Division | Generalleutnant Erwin Sander | Completely worn out and used as tactical reserve |

| 256. Volksgrenadier-Division | Generalmajor Gerhard Franz | Good, experienced division equal to three weakened regiments |

| OPERATION SONNENWENDE | |

| Heeresgruppe Oberrhein | Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler |

| 19. Armee | General der Infanterie Siegfried Rasp |

| LXIV Armee Korps | General der Infanterie Hellmut Thumm |

| 189. Infanterie-Division | Generalmajor Eduard Zorn |

| 198. Infanterie-Division | Generalmajor Otto Schiel |

| 708. Volksgrenadier-Division | Generalmajor Wilhelm Bleckwenn |

| 16. Infanterie-Division | Generalmajor Alexander Moekel |

| LXIII Armee Korps | General der Infanterie Erich Abraham |

| 338. Infanterie-Division | Generalmajor Konrad Barde |

| 159. Infanterie-Division | Generalmajor Heinrich Bürcky |

| 716. Infanterie-Division | Generalmajor Wolf Ewert |

| 269. Infanterie-Division | Generalleutnant Hans Wagner |

The US Army in Alsace was stretched very thinly but was in substantially better shape than the Wehrmacht. Although US infantry divisions were fewer in number than their Wehrmacht counterparts, they were kept closer to authorized strength. For example, in the initial operations in the Vosges in early October, Seventh Army deployed three infantry divisions and a separate regiment with a total of 17,695 infantry, while the opposing AOK 19 had 10–12 divisions but only 13,100 infantry. During the fighting in the Low Vosges in mid-December 1944, the four US infantry divisions involved had 77 percent of their authorized strength in their rifle companies, ranging from a high of 88 percent (103rd Division) to a low of 66 percent (45th Division).

The Seventh Army Divisions fell into roughly three categories: experienced but battle-weary, new but partly battle-experienced, and new and unprepared. Three infantry divisions had served with the Seventh Army since the Operation Dragoon landings and had previously served in the Mediterranean theater seeing their combat debut in North Africa (3rd Division), Sicily (45th Division), and Salerno (36th Division). These three were amongst the most battle-tested in the US Army in Europe, and were accustomed to the rigors of mountain combat. Three other divisions had seen their combat debut in Normandy with Haislip’s XV Corps (44th and 79th Divisions, and 2e Division Blindée). Two divisions had entered combat recently, the 100th Division which entered combat in the Vosges in early November 1944 and the 103rd Division which entered combat in the Vosges in mid-November. While not having the experience of the veteran divisions, these new divisions had seen enough combat in the autumn fighting that they were prepared for the upcoming German offensive.

| SEVENTH US ARMY, 1 JANUARY 1945 | ||

| XV Corps | Maj. Gen. Wade Haislip | |

| 103rd Division | Maj. Gen. Charles Haffner | 409th, 410th, 411th Infantry |

| 44th Division | Brig. William Dean | 71st, 114th, 324th Infantry |

| 100th Division | Maj. Gen. Withers Burress | 397th, 398th, 399th Infantry |

| Task Force Harris (63rd Div.) | Brig. Gen. Frederick Harris | 253rd, 254th, 255th Infantry |

| VI Corps | Maj. Gen. Edward Brooks | |

| Task Force Hudelson | Col. Daniel Hudelson | 94th CRSM, 62nd AIB, 117th CRSM |

| 45th Division | Maj. Gen. Robert Frederick | 157th, 179th, 180th Infantry |

| Task Force Herren | ||

| (70th Division) | Brig. Gen. Thomas Herren | 274th, 275th, 276th Infantry |

| Task Force Linden | ||

| (42nd Division) | Brig. Gen. Henry Linden | 222nd, 232nd, 242nd Infantry |

| 79th Division | Maj. Gen. Ira Wyche | 313th, 314th, 315th Infantry |

| XXI Corps/SHAEF Reserve | Maj. Gen. Frank W. Milburn | |

| 12th Armored Division | Maj. Gen. Roderick Allen | 23rd, 43rd, 714th TB; 17th, 56th, 66th AIB |

| 14th Armored Division | Maj. Gen. Albert Smith | 25th, 47th, 48th TB; 19th, 62nd, 68th AIB |

| 36th Division | Maj. Gen. John Dahlquist | 141st, 142nd, 143rd Infantry |

| 2e Division Blindée | Gen. Div. Jacques Leclerc | 12e RC, 12e RCA, 501er RCC, RMT |

| AIB = Armored Infantry Battalion: CRSM = Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron (Mechanized) Infantry = Infantry Regiment: TB = Tank Battalion: (See below for French abbreviations) | ||

The sudden extension of the Seventh Army to cover parts of the Third Army sector in late December forced Devers to commit elements of three divisions that had recently arrived in Marseilles: the 42nd, 63rd, and 70th Divisions. While still in the United States, these divisions had been heavily cannibalized for precious riflemen in the spring and summer of 1944 due to shortages in the ETO. These divisions were in such rocky shape that they were not supposed to be deployed until training was complete in July 1945; instead they were hastily shipped to France in December 1944. The 63rd Division had received 1,374 new replacements since the autumn while the 70th had received a whopping 3,871 new troops; neither division had completed the standard 12-week large-scale maneuver phase of training. To make matters worse, none arrived intact with all its component elements. Due to the desperate need for infantry, Devers ordered the infantry regiments of these two divisions forward. Since they were not ready to participate in the fighting as divisions, they were temporarily deployed as task forces, and subordinated to more experienced divisions. Typically, their component regiments were thrown into combat separately. These formations were by far the weakest and least prepared of the US infantry units to take part in Operation Nordwind, and were derisively referred to as “American Volksturm Grenadiers” by some of the more experienced US infantry units. While the three late-arriving American infantry divisions were of poor quality compared with the rest of Seventh Army, they were certainly no worse than the vast majority of the Wehrmacht infantry taking part in Operation Nordwind.

The US infantry formations had numerous advantages over their German opponents in terms of armored and artillery support. In contrast to the German infantry divisions, which were lucky to have a company of 14 assault guns, all US infantry divisions had a tank battalion and a tank destroyer battalion attached. The tank battalions were organized in a standardized fashion with three companies of M4 (Sherman) medium tanks and a company of M5A1 (Stuart) light tanks. The tank destroyer battalions were mainly equipped with the M10 3in. GMC (gun motor carriage) and one battalion had the new M36 90mm GMC, the most powerful tank destroyer in service at the time. Only a single battalion was equipped with the inferior towed 3in. guns. The newly arrived 827th Tank Destroyer Battalion (Colored) had the new M18 76mm GMC; this was one of a small number of segregated African-American units in the Seventh Army. The US infantry divisions enjoyed significantly better artillery support than the Wehrmacht both in terms of better divisional artillery, more corps artillery, a far more ample supply of ammunition, and better radio-coordinated fire direction.

Unlike the VI Corps divisions, which came into France from the Mediterranean theater, the 44th Division was one of three XV Corps units that landed in Normandy and joined the Seventh Army in Lorraine in the autumn after taking part in Patton’s race to the Seine. During Operation Nordwind, the division was on the Seventh Army’s left flank and helped defeat the assault by the 17. SS-Panzergrenadier Division. Here, the divisional commander, Brig. Gen. William Dean, inspects a 57mm anti-tank gun position at the front lines near Herbitzheim on January 24, 1945. Dean is better known as the commander of the 24th Infantry Division in Korea in 1950, when he won the Medal of Honor for conspicuous bravery in trying to stem a North Korean attack. (NARA)

| SEVENTH ARMY, DIVISIONAL ARMOR ATTACHMENTS – JANUARY 1, 1945 | ||

| Infantry Division | Tank Bn. | Tank Destroyer Bn. |

| 3rd | 756th | 601st (M10 3in. GMC) |

| 36th | 753rd | 636th (M10 3in. GMC) |

| 44th | 749th | 776th (M36 90mm GMC) |

| 45th | 191st | 645th (M10 3in. GMC) |

| 79th | 781st | 813th (M10 3in. GMC) |

| 100th | 824th (towed 3in.) | |

In terms of armor, the Seventh Army could count on three armored divisions compared with the Wehrmacht’s one Panzer and two Panzergrenadier divisions. The American and French units were substantially better equipped and near full strength. Of the three Allied divisions, the French 2e Division Blindée was by far the most experienced. The 14th Armored Division had been committed to small-scale action in November 1944 but was not yet fully seasoned. Devers was not happy with its progress, but at least it had some combat exposure. The 12th Armored Division had only recently arrived in theater and was completely inexperienced, as would become painfully apparent in the January fighting. As of the second week of January 1945, the Seventh Army had 704 medium tanks of which 167 were M4A3 (76mm), 50 were M4 (105mm), and the rest were the standard 75mm versions. There were also 376 light tanks, mostly the M5 and M5A1 in US units and the M3A3 with the French 2e Division Blindée. The 6th Army Group as a whole had substantial armored forces when the French 1ère Armée and separate tank battalions are considered. As of mid-December 1944, the 6th Army Group had 1,131 Sherman medium tanks, 697 light tanks, and 504 self-propelled tank destroyers.

The other extemporized unit deployed by Seventh Army in late December was Task Force Hudelson, which was created to cover the gap between XV and VI Corps immediately south of Bitche. This consisted of three units from the 14th Armored Division: the 94th Cavalry Squadron, 62nd Armored Infantry Battalion, and 400th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, plus the Seventh Army’s reconnaissance unit, the 117th Cavalry Squadron, and a variety of supporting engineer and other units. This hastily created unit was assigned to screen a wide 15-mile (24km) stretch of the Low Vosges from Bitche to Drachenbronn, a heavily forested and mountainous sector which Patch considered the easiest to defend. While this later proved to be true, this sector also happened to be the focus of one of the two major German thrusts and Task Force Hudelson would initially be outnumbered by a ratio of more than ten to one.

6th Army Group’s air support was not especially generous by US standards although certainly more extensive than the non-existent Luftwaffe support of Heeresgruppe G. The 1st Tactical Air Force (Provisional) was created in October 1944 to coordinate the American XII Tactical Air Command with the French 1er Corps Aérien Français. The XII TAC included four P-47 fighter-bomber groups, each numbering about 36 aircraft, and two B-26 medium bomber groups. The French units were in the process of being re-equipped from a hodgepodge of British and American cast-offs and eventually included three P-47 and two B-26 escadres (groups).

The Free French Army was in the midst of transition in the autumn of 1944 and faced some unique problems. The first two divisions of de Gaulle’s Free French movement were the 1ère Division Motorisée d’Infanterie (1re DMI) raised with British help, and the 2e Division Blindée (an armored division) raised with US support. Both divisions relied heavily on volunteers, especially from the French colonies in North Africa. The remainder of the divisions were created out of the former Vichy Army of Africa, which switched sides after the November 1942 Allied invasion of French North Africa. The matter of recreating the French army was taken over by the United States due to the bitter relations between Britain and France after the 1940 debacle and the subsequent British sinking of the French fleet. Under the Anfa Plan approved by President Franklin Roosevelt during the Casablanca conference in January 1943, the US pledged to raise and equip nine infantry and three armored divisions.

Four French infantry divisions were committed to Italy under Général Alphonse Juin with the Corps Expéditionnaire Français (CEF) and fought with considerable distinction in the tough mountain fighting to the east of Monte Cassino in early 1944. In the meantime, Gén. Jean de Lattre de Tassigny raised three more divisions, the 1ère and 5e Divisions Blindées and the 9e Division d’Infanterie Coloniale (DIC). De Gaulle wanted all French units committed to the liberation of France, so the CEF was extracted from Italy and amalgamated with de Lattre’s forces, which became the 1ère Armée (First Army) alongside Patch’s US Seventh Army. With the exception of the 1ère DMI, which was equipped by the British, the Free French units raised in North Africa in 1943/44 were armed and equipped by the US Army and followed US organizational patterns while at the same time retaining distinctly French regimental lineage. This can lead to some confusion as the infantry divisions bore the traditional French designations of mountain division, colonial division and so on while in fact they all had the same organization; tank units retained their regimental designations though in fact they followed US tank battalion organization.

The new divisions were formed from a mixture of sources, in some cases absorbing units from the Army of Africa, and in other cases being formed through conscription in the North African colonies. French conscription policy recognized two categories, “européens” and “indigènes”, referring to French settlers in North Africa and the indigenous Algerian, Tunisian, and Moroccan population. Sub-Saharan colonial troops were usually designated as “sénégalais” though in fact they came from a variety of French colonies including Madagascar, the Ivory Coast, and Senegal. The mobilization brought in more “indigènes” than French, amounting to 105,700 by the end of 1944 compared with 48,400 French settlers.

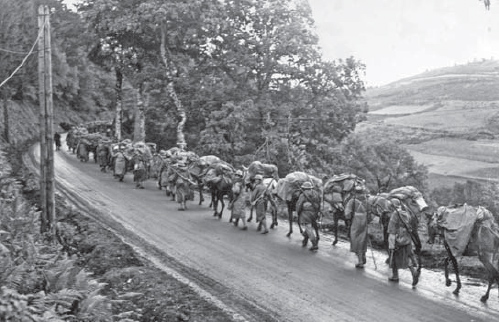

The colonial units of the French army still relied heavily on horses and mules for transport, which were archaic but very effective in the Vosges, as can seen here with a supply column of the veteran 3e Division d’Infanterie Algérienne in the hills near Rupt on October 4, 1944. (NARA)

The colonial troops had fought with distinction in both Italy and in the summer and early autumn fighting in France, but there was growing political pressure to reorganize the French army with more troops from metropolitan France. The colonial units had borne an unfair and heavy burden from 1942 to 1944, suffering considerable losses amongst their rifle companies. There was resistance in the colonies to dispatching large additional levies after the liberation of most of metropolitan France in the summer of 1944. Casualties amongst experienced French colonial officers had also been high, and the hardened colonial troops were often surly and uncooperative under the direction of green French officers who knew little of their language or customs. Furthermore, there were some concerns that the African troops, and especially the Senegalese units, would have a hard time coping with the winter conditions in Alsace.

The obvious sources for fresh troops were the numerous FFI (Forces Françaises de l’intérieur) resistance units, which had grown wildly in number in 1944. De Gaulle’s government was insistent on amalgamating these units into the regular army, as there was some concern that they would be used as political militias to impose their own parties in power in various localities; the groups were not well disciplined and had been a source of civil disorder after the liberation. This process began in the summer of 1944 and many of the newly formed units were deployed in the sieges at the Atlantic ports still in German hands such as Lorient, St Nazaire, and Royan. Only one of the FFI divisions, the 10e Division d’Infanterie under Général Bilotte, was committed to the fighting in Alsace.

“Les indigènes,” France’s North African colonial troops, bore the brunt of the infantry fighting in Alsace in the autumn and winter of 1944/45. These are Algerian troops of the experienced but weary 3e Division d’Infanterie Algérienne, which had fought in Italy in 1943/44, then again in southern France and Alsace in 1944/45. (NARA)

To relieve the excessive dependence on France’s North African colonies for the supply of troops, the 1ère Armée began a process of “whitening” in the autumn of 1944, first reinforcing the colonial regiments with supplementary units formed from FFI resistance units, then substituting FFI troops for colonial troops in the regular regiments. (NARA)

By the end of October 1944, the 1ère Armée had already absorbed about 60,000 FFI troops into its ranks, in many cases by attaching FFI battalions as a supplementary fourth battalion to existing infantry regiments. In addition, a process had begun to integrate individual FFI members and volunteers into the Army. The process of “blanchisement” (whitening) of the 1ère Armée continued through most of the autumn. The 1ère Division de Marche d’Infanterie (DMI) received about 6,000 FFI troops, while the 9e DIC was reorganized first through the adoption of FFI sub-units, then by direct replacement of its 9,200 Senegalese troops. The three North African mountain divisions (2e, 3e, and 4e DIA) were kept at strength by replacing one regiment in each division with FFI troops. The process was a prolonged and complicated affair as the French commanders did not want to substitute poorly trained and ill-disciplined FFI troops for tough and well-disciplined North African troops in the midst of combat operations. Since the US was reluctant to supply numerous ad hoc 1ère Armée units with weapons, supplies, and equipments, the French army attempted to generate equipment through French channels such as the use of 1940 French equipment left behind by the Germans. By 1945, some 137,000 FFI troops were absorbed into the 1ère Armée. Many of the colonial troops replaced in the infantry divisions were reassigned to other areas, such as the new units assigned to the French–Italian border.

The US supply of arms to the rejuvenated French Army was not limitless, so de Gaulle’s government made efforts to develop its own sources, especially the use of refurbished arms from the 1940 arsenals left behind by the Wehrmacht during its retreat from France in 1944. A total of 72 of the 155mm Grande Puissance Filloux (GPF) guns were in service with the 1ère Armée by 1945, and this battery is seen in action during the reduction of the Colmar Pocket in February 1945. (NARA)

De Lattre continually complained to Devers about the imbalance in supplies between the lavishly equipped Seventh Army and the ragtag 1ère Armée. While the US did give priority to the Seventh Army in some areas, the problem was partly the result of French decisions to focus on the combat elements of the 1ère Armée at the expense of logistical support. Its logistics agency, Base 901, numbered 29,000 troops when a comparable US organization would have numbered 112,000 to support the army’s eight divisions.

To complicate matters further, de Gaulle had been pressing Eisenhower to divert some of de Lattre’s forces to help clear the Gironde estuary on the approaches to the port of Bordeaux. The Allies had priority for ports on the Atlantic, and de Gaulle wanted the port freed from the German garrisons to provide a port for French civil use. This effort was codenamed Operation Liberty, and Devers was instructed to free the 1ère DMI and 1ère Division Blindée for this operation in late 1944. Not only did he object to this diversion, but de Lattre and his corps commanders continued to drag their feet since it would disrupt their combat operations in the Belfort Gap.

| 1ère ARMÉE, LATE JANUARY 1945* | ||

| 1ère Armée Française | Gén. Jean de Lattre de Tassigny | |

| 1er Corps d’Armée | Gén. Antoine Béthouart | |

| 1ère DMI (Division de Marche d’Infanterie) | Gén. Diego Brosset, | 1er BI, 2e BI, 4e BI, 1er RA |

| 2e DB (Division Blindée) | Gén. Jacques Leclerc | 12e RC, 12e RCA, 501 er RCC, RMT |

| 3e DIA (Division d’Infanterie Algeriénne) | Gén. Augustin Guillaume | 3e RTA, 7e RTA, 4e RTT, 67e RAA |

| 2e Corps d’Armée | Gén. Joseph de Goislard de Monsabert | |

| 1ère DB (Division Blindée) | Gén. Aimé Sudré | 2e RC, 2e RCA, 5e RCA, 1er DBZ, 68e RAA |

| 9e DIC (Division d’Infanterie Coloniale) | Gén. Joseph Magnan | 4e RTS, 6e RTS, 13 RTS, RACM |

| 2e DIM (Division d’Infanterie Marocaine) | Gén. Marcel Carpentier | 4e RTM, 5e RTM, 8e RTM, 63e RAA |

| 4e DMM (Division Marocaine de Montagne) | Gén. René de Hesdin | 1er RTM, 2e RTM, 6e RTM, 69e RAM |

| 5e Division Blindée | Gén. Henri de Vernejoul | 1er RC, 1er RCA, 6e RCA, RMLE, 62e RAA |

| 10e Division d’Infanterie | Gén. Pierre Bilotte | 5e RI, 24e RI, 46e RI, 32e RA |

| *Does not include attached US Army XXI Corps | ||

| BI = Brigade d’Infanterie; DBZ = Demi-Brigade de zouaves; RA = Régiment d’artillerie; RAA = Régiment d’artillerie d’Afrique; | ||

| RACM = Régiment d’artillerie colonial du Maroc; RAM = Régiment d’artillerie marocaine; RC = Régiment Cuirassiers; | ||

| RCA = Régiment de Chasseurs d’Afrique; RCC = Régiment de chars de combat; RFM = Régiment de Fusiliers-Marins; | ||

| RI = Régiment d’infanterie; RMLE = Régiment de marche de la Légion Etrangère; RMT = Régiment de marche du Tchad; | ||

| RTA = Régiment de tirailleurs algériens; RTM = Régiment de tirailleurs marocains; RTS = Régiment de tirailleurs sénégalais; | ||

| RTT = Régiment de tirailleurs tunisiens | ||