The most famous ring legend of the Norsemen is told in the ‘Volsunga Saga’. The epic tale is one of the greatest literary works to survive the Viking civilization. Within the ‘Volsunga Saga’ is the history of many of the heroes of the Volsung and Nibelung* dynasties. In the nineteenth century William Morris wrote of the epic: ‘This is the great story of the North, which should be to all our race what the tale of Troy was to the Greeks.’

The fates of the Volsung and Nibelung dynasties were bound up with that of a magical ring called ‘Andvarinaut’. This was the magical ring that once belonged to Andvari the Dwarf. It seems to have been an earthly Draupnir. Its name means ‘Andvari’s loom’ because it ‘wove’ its owner a fortune in gold; and with that wealth went power and fame. The tale of Andvarinaut has become the archetypal ring legend, and is primarily concerned with the life and death of the greatest of all Norse heroes, Sigurd the Dragonslayer.

It is this legend of Sigurd and the Ring as told in the Volsunga Saga that in various forms survives in the modern imagination as the ring legend. William Morris brought the first satisfactory direct translation of the Volsunga Saga into the English language. His later long epic poem ‘Sigurd the Volsung’, Henrik Ibsen’s play The Vikings of Helgeland, and - above all - Richard Wagner’s great opera cycle The Ring of the Nibelung brought the epic tale into the popular European imagination in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

In this chapter, the Volsunga Saga is retold. It should be noted that the epic is a collection of over forty linked but individual saga tales. These were the final outcome of an oral tradition of diverse authorship composed over many centuries. The resulting texts therefore often result in a somewhat irregular plot structure, although the overall outline is clear. In this retelling, those parts of the saga concerning the ring are emphasized in detail, while peripheral adventures (particularly those that precede the appearance of Sigurd) are told in synopsis form.

Readers will find many parallels between the Volsunga Saga and Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion. Rather than break up the tale with interjections, these parallels will be examined later, along with comparisons with the legends of King Arthur, Charlemagne, Dietrich von Berne, and numerous other heroes and traditions; including the medieval German Nibelungenlied and a score of fairy tales.

The Volsunga Saga begins with the tale of the hero Sigi, who is the mortal son of Odin. He is a great warrior who by his strength and skill becomes the King of the Huns. King Sigi’s son is Reric, who is also a mighty warrior, but cannot give his queen a child and heir. So the gods send to Reric a crow with an apple in its beak. Reric gives this apple to his wife, who eats it and becomes heavy with child. But the child remains in his mother’s womb for six years before he is released by the midwife’s knife. This child is Volsung, who becomes the third in this line of kings.

Volsung is the strongest and most powerful of all the kings of Hunland. He is a man of huge physical size and he sires ten sons and one daughter. The eldest of his children are the twin brother and sister, Sigmund and Signy.

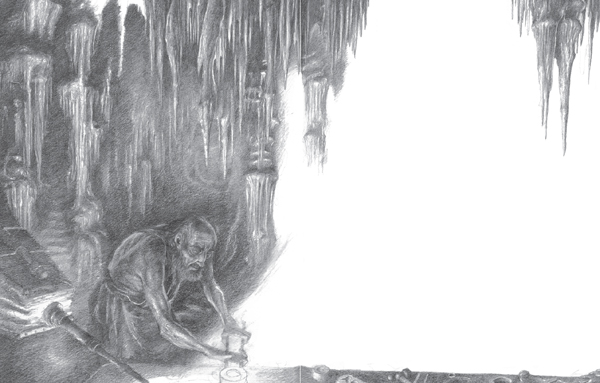

One day a grey-bearded stranger with one eye appears in the great hall of the Volsungs in the midst of a great gathering of Huns, Goths and Vikings. Without a word, the old man strides over to Branstock, the great living oak tree that stands in the centre of the Volsungs’ hall. He draws a brilliant sword from a sheath and drives it up to its hilt in the tree trunk. The ancient stranger then walks out of the hall and disappears.

No mortal man could have achieved such a feat, and all know that this old man can be none other than Odin. All the heroes in the great hall desire this sword, but only Sigmund has the strength to draw it from Branstock. All know that, armed with Odin’s sword, Sigmund is the god’s chosen warrior.

With this sword, which can cut stone and steel, Sigmund wins great fame, yet terrible tragedy soon befalls the Volsung family. Sigmund’s sister is married to the King of Gothland, who treacherously murders King Volsung at the wedding feast. He then imprisons Volsung’s ten sons by placing them in stocks in a clearing in the wild wood. One son is torn to pieces each night for nine nights by a Werewolf, who is actually the witch-mother of the king. However, on the tenth night, Sigmund (with the help of his sister Signy) manages to trick the Werewolf and slays her by tearing out her tongue with his teeth.

Sigmund escapes and lives for many years as an outlaw in an underground house in the wild wood. Signy’s desire for vengeance is so great that, while remaining the wife of the King of Gothland, she casts a spell on Sigmund. When she comes to his underground house, he does not know it is his own sister and makes love to her. Months later, Signy has a child from this incestuous union. He is called Sifjolti, and when he is grown, Signy sends him to Sigmund in the wild wood, so together they may avenge Volsung’s death.

After many trials, including stealing and wearing Werewolf skins and being buried alive in a barrow grave, Sigmund and Sifjolti set fire to the great hall of the Goth king. Signy secretly returns Odin’s sword to Sigmund, and all who attempt to escape the fire are slain. Seeing the Goth king and his kin slain, Signy confesses the price she has paid to exact her revenge, including incest with her brother, and leaps into the flames.

Sigmund returns with Sifjolti to his homeland and claims his father’s throne as King of Hunland. He rules successfully for many years, although his son Sifjolti dies by poisoning. Shortly after King Sigmund marries the Princess Hjordis, two armies of Vikings ambush Sigmund. However, they fail to slay him because of his supernatural sword. Into the fray of battle comes an ancient, one-eyed warrior. When Sigmund strikes this old man’s spear shaft with his sword, the blade shatters. Sigmund knows his doom has come. The ancient warrior can be none other than Odin. Sigmund’s enemies strike him down.

Sigmund is given mortal wounds by his enemies, yet he does not despair for he has lived long and he knows that his queen is heavy with child. The dying Sigmund tells his wife she must take the shards of Odin’s sword. For Sigmund knows the prophecy that he will sire a son who, with the sword reforged, will win a prize greater than that of any mortal man.

Sigmund’s queen flees the battleground and after a long journey finds refuge in the Viking court of the King of the Sea Danes. There, the exiled queen gives birth to her son, Sigurd, and raises him in secret under the protection of the Danes.

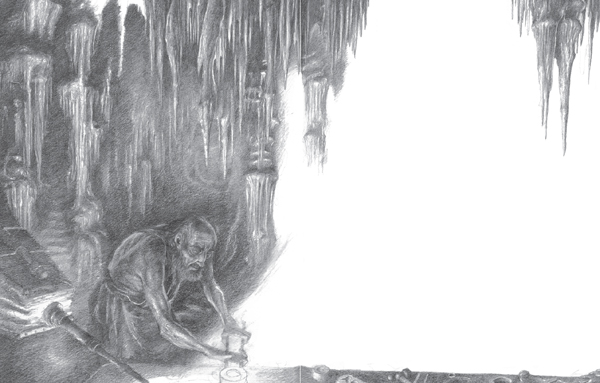

Now in the realm of the Sea Danes is a master smith. He is called Regin, and from his long, toiling hours at the forge, his powerful body is hunched and stunted like a Dwarf’s. Yet from his fire and forge comes much beauty in jewels and bright weapons. Swords, spears and axes shine with a bright sheen. None know their equal.

No one knows Regin’s age or his past. He entered the land of the Danes before the memory of the oldest king. He is no lord of fighting men, but a smith and a master of other crafts as well. He is filled with the wisdom of runes, chess play, and the languages of many lands.

But Regin casts a cold eye on life, and none knows him as a friend. So the Sea-Dane King is much surprised when Regin fosters Sigurd and becomes his tutor. There never was a pupil like Sigurd, so quick and eager to learn. He is well taught by the smith in many arts and disciplines, though in the warrior’s skills he excels most. Teacher and pupil are a strange pair. Some say Regin is too cold-tempered, and Sigurd born too hot. Whatever the reason, over the years of learning, master and apprentice never form a bond of love or close friendship.

Wise though Sigurd becomes with Regin’s teaching, there is something in his blood that beckons him to learn matters that are even beyond the smith’s teachings. So Sigurd often goes to the forest for many days of wandering. On one such solitary journey, Sigurd meets an ancient man in a cape and a wide-brimmed slouch hat. The old man’s bearded face has but one eye, and he uses a spear as a walking-stick. This man tells Sigurd he may choose whatever horse he wishes for himself from his herd in the meadow.

When Sigurd chooses a young grey stallion, the old man smiles.

‘Well chosen. He is called Grani, meaning grey-coat, and he is as sleek as quicksilver and will grow to become the strongest and swiftest stallion ever to be ridden by a mortal man. For Grani’s sire was the immortal Sleipnir, the eight-legged stallion of Asgard, who rides stormclouds over the world.’

Not long afterwards, Regin sends for the youth.

‘You have grown large and strong, Sigurd. Now is the time for an adventure,’ says Regin. ‘I have a tale to tell.’

The two then go out onto the green grass before Regin’s hall. By an oak tree there is a stone bench on which the smith settles, while the huge youth sits on the grass at his feet.

‘Know me now, young Sigurd, for what I am. Not a man, but one born in a time before the first man entered the spheres of the world. This was a time almost before there was Time. Giants and Dwarfs were filled with terrible strength, and there were Magicians of such power that even the gods feared to walk alone across the lands of Midgard.

‘In this time, the gods Odin, Honir and Loki went on an adventure into Midgard and dared to enter the land of my father, Hreidmar, the greatest Magician of the Nine Worlds. On the first day, the three gods came to a stream and a deep pool. Resting a while, they soon saw a lithe brown otter swimming in the pool. Diving deep, the otter caught a silver salmon in its jaws and, reaching the far shore, struggled to drag his prize out of the water. It seemed an opportunity not to be missed. Without a word, Loki hurled a stone and broke the otter’s skull.

‘Loki rejoiced at having won both otter and salmon with a single stone. He went to the otter and skinned it. Taking up their double prize of salmon and otter skin, the three gods walked on until evening, when they came to a great hall upon a fair heath. This was Hreidmar the Magician’s hall, which stood on the Glittering Heath just above the dark forest called the Mirkwood.

‘When the three gods entered the hall, they made a gift of the salmon and the otter skin to their host. The Magician immediately flew into a rage, and bound the gods at once with a deadly spell. Then he called to me, to bring my fire- forged chains of unbreakable iron; and he called to my brother, the mighty Fafnir, to bind these gods tightly with my chains and his pitiless strength. Once this was done, no one but the Magician-King might ever free those three gods.

‘Although my father much admired my craft and Fafnir’s strength, it was his third son that he loved best. This son was the Magician’s eyes and ears. He was a shape-shifter who travelled often in many forms of bird and beast, and told my father what went on in the wide world. He was called Otter after his favourite guise.

‘This was the reason for the Magician-King’s terrible wrath. The otter that the gods slew at the pool, then unknowingly offered as a gift, was the flayed skin of their host’s favourite son.

‘For this outrage, the Magician was intent on the destruction of all three who slew his son. But Odin spoke persuasively, saying truthfully that Otter was slain in ignorance; and that in such cases, payment of weregild instead of blood was just and honourable compensation. Though much grieved, the Magician-King laid the terms.

‘“Fill my son’s skin with gold and cover him with it too. Do that and I will spare you,” he demanded, grimly.

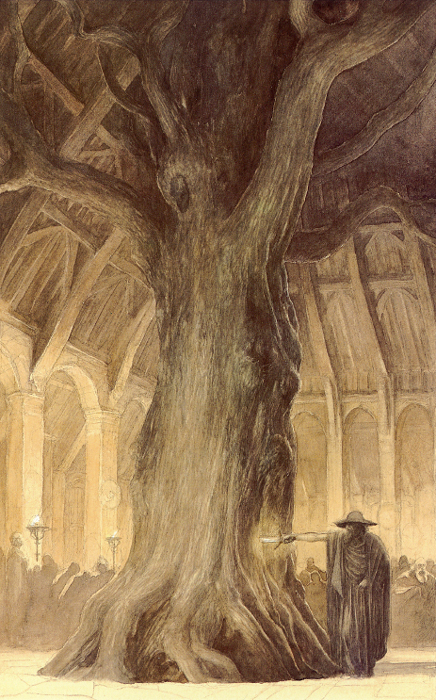

‘Since Loki had cast the fatal stone, he was chosen to find the weregild, while the others remained bound. Odin advised him to quickly find the Dwarf Andvari, who was renowned for his wealth. This hoard of gold he hid in a mountain cavern beneath a waterfall. Yet Odin warned that Andvari the Dwarf was also a shape-shifter who hid his identity. Most often, he took the form of a great pike who lived in the pool beneath the falls, so he might better guard his watery treasury door.

‘Loki was not long in finding the waterfall. He stared hard into the clear pool and saw the great pike hiding in the eddies under the rocks. He dragged the pike to the land where, gasping, it took on Andvari’s true shape and begged for mercy. Loki was not gentle. He twisted the Dwarf until his screams drowned out the sound of the water. Finally Andvari gave up his golden treasure to Loki, but the Dwarf begged that he might be allowed to keep just one red-gold ring for himself. Guessing at the ring’s importance, Loki snatched the ring from Andvari as well, and hurried on his way.

‘Now this was the ring called Andvarinaut, which means “Andvari’s loom”, for by its power gold comes, and treasure increases ever more. This golden ring breeds gold, though this was but one of its powers; many of its other powers are unknown. This one small red-gold ring that Loki stole was worth all the rest of treasure together.

‘The Dwarf screamed after him: “I curse you for this! The ring and the trea- sure it spawned will carry my curse forever. All who possess the ring and its treasure for long will be destroyed!”

‘Loki returned to the Magician’s hall with the gold hoard and stuffed Otter’s skin tight with it, and piled gold over all. The price in weregild seemed to be made, but the Magician-King looked keenly at the treasure and pointed to one whisker that still protruded. Loki smiled grimly then, and let fall the ring Andvarinaut which he had held back. The ring covered the last hair and the payment was made.

‘The Magician-King packed up the treasure in great oak chests, but took the ring Andvarinaut and placed it on his hand. Then he released the bonds of his spell, commanded Fafnir and me to unlock the chains, and the gods were given safe passage out of his land.

‘For a short time, all seemed well, but the mere sight of the ring was a torment to Fafnir. And so, one night Fafnir crept to our father’s bed and cut his throat while he slept. He placed Andvari’s ring on his own hand, then appeared at my bedside with his bloody dagger.

‘“Come,” he said, “I have need of you.”

‘Fearfully I did as I was told and dragged the treasure out across the Glittering Heath and beyond to a cavern under a mountain deep in the Mirkwood.

‘“You make a good porter, my brother. You’ve earned your life, but little else.

If you turn now and run, I will not slay you. Put this gold from your mind, for it shall never be left unguarded.”

‘So it was that Fafnir won the ring and the treasure of the Dwarf Andvari with the blood of our father. Over that treasure, he ever after brooded. Hateful lust has poisoned his heart and mind, and all who have come his way by chance or intent, he has murdered. For now his outward form has matched his inner evil, and he has become a serpent: a huge dragon, the mightiest of this or any age.’

Sigurd now sees his destiny and takes up Regin’s challenge.

‘Slay me this dragon to avenge my father, and win for yourself great glory,’ commands Regin. ‘Help me to my share of the weregild, and besides glory you shall have Andvari’s ring and the greater part of the treasure, as well.’

For such a mission, the valiant Sigurd desires a weapon to match his strength, and so goes to his mother and claims the shards of his father’s sword that had been the gift of Odin. These shards he gives to Regin in his smithy. Regin sets furiously to work, heating them in the hottest fire, reforging the blade and tempering it in the blood of a bull. The sacred runes above the hilt recover their brightness, the rings engraved on the steel gleam like silver, and as the smith carries the sword out into the daylight, it seems that flames play along its edge.

Sigurd takes the weapon in his strong hands and swings it fiercely at the smith’s anvil. The sword slices clean through the iron and the wooden stock below it, as well. Yet the blade is unnotched by the stroke.

‘This truly can be no other but the sword called Gram, the gift of Odin, which my father swore would one day be reforged and be given to his only son,’ says Sigurd, smiling.

So armed and mounted on his steed Grani, Sigurd rides on his quest with Regin. They come at last to the fire-scorched and desolate outlands of what was once the Glittering Heath. Now this place is wild and blasted heath on the edge of the evil forest of Mirkwood. It is a scorched wasteland where many a hero was slain by the dragon. Upon this heath is cut a deep path of stone that is the slime-filled track of a dragon road. The road leads to Fafnir’s serpent cavern deep in the Mirkwood. There the dragon made his bed upon the golden treasure that was the ring-hoard of Andvari the Dwarf. Fafnir left his golden bed only once each day, when he travelled his road to the foul pool on the heath where he drank at dusk.

‘Dig a trench in the dragon’s path and hide in it,’ advises Regin. ‘When he comes over you thrust your sword up into his soft belly. You cannot fail.’

While Sigurd is digging, Regin makes off across the heath and hides himself in the Mirkwood. A shadow falls over the pit and Sigurd whirls around. It is the same one-eyed, bearded old man who had given Sigurd his grey horse.

‘Small wisdom, short life,’ murmurs the old man, leaning on his spear. ‘The dragon’s blood will sear your bones. Dig several pits, and hide in the one to the left. Then you may thrust your blade into the worm’s heart, while the boiling, poison blood falls into another pit.’

By evening the work is done, and just in time. The stinking dragon comes down to drink, roaring horribly and slavering poison over the ground. Biding his time, Sigurd thrusts Gram’s blade into the dragon’s breast up to the hilt. The scalding, corrosive blood floods into the ditch, and Fafnir collapses. His writhing coils shake the earth, his roaring fills the air with flame and venom. His jaws snap at an enemy he cannot reach, as he curses the hero who has slain him and the brother who betrayed him.

When Sigurd emerges from his pit, Regin too comes from his hiding-place and feigns both sorrow and joy. Claiming that he wishes to remove any blood guilt from Sigurd for the slaying of Fafnir, Regin asks Sigurd to cut the dragon’s heart from its body and roast it. Regin claims that by eating the dragon’s heart, he alone might be brought to account for its death.

Sigurd does as Regin tells him and builds a fire and spits the heart over the flames. But as the dragon’s heart cooks, its juice spits out and scalds the young man’s fingers. He puts his fingers in his mouth and, upon tasting the monster’s heartblood, at once finds he can understand the language of the birds in the trees about him.

The birds speak with sorrow, for they know of Regin’s treachery. How the smith will gain great wisdom and bravery by eating the dragon’s heart, then plans to slay Sigurd in his sleep. The birds know that Regin will never share the golden treasure, nor the ring with the brave youth, despite his sworn oath. They know as well that Regin wishes to steal Sigurd’s sword and steed.

Hearing this talk among the birds, Sigurd moves swiftly. With his sword Gram, he strikes the false smith’s head from his shoulders. Then, Sigurd eats the dragon’s heart himself and sets to work clearing out Fafnir’s lair.

It is a whole day’s work, for the cave floor is carpeted with drifts of gold. No three horses could have stood beneath such a load, but Grani carries this with ease. The extra burden of Sigurd, now wearing golden armour, seems to cause him no effort at all.

So laden, with the Ring of Andvari on his hand, Sigurd the Dragonslayer goes out of that burnt wasteland in search of more adventures. He seeks and achieves further honour, for he makes war on all the kings and princes who murdered his father and his kinsmen, and slays them every one.

Many other adventures the youth has as well, but then he goes south into the Lands of the Franks. Travelling long one night he sees, like a beacon, a great ring of flames on a mountain ridge. The next morning he climbs that ridge called the Hindfell, where he sees a stone tower in the midst of the ring of flames.

Sigurd does not hesitate. He urges Grani into the ring of fire. Nor does Grani flinch. His leap is as high as it is long, and though his tail and mane are scorched, he stands quietly once they are through. There is an inner circlenext: an overlapping ring of massive war shields, their bases fixed in the mountain rock. Sigurd draws Gram and shears a path through the iron wall of shields.

Beyond this is a stone tower, and within it is the body of a warrior on a bier. Or so it seems. When Sigurd takes the helmet from the warrior’s head, he sees that this is a woman and that she is not dead, but sleeping. As he gazes on her, Sigurd sees she is of a warrior’s stature and a woman’s grace. He also sees a buckthorn protruding from her neck. When Sigurd draws it out, this sleeping beauty sighs and wakes. The shield maiden’s steady grey eyes look up at him with love.

This sleeping beauty is Brynhild, who was once a Valkyrie, one of Odin’s own battle maidens - his beautiful angels of death - who gathered the souls of heroes as they fell in war and carried them to Valhalla. But once, she set her will against Odin in the matter of a man’s life. For this, Odin pierced her with a sleep-thorn and set her in a tower surrounded by a ring of fire.

Only a hero who did not know fear would be able to pass through the ring of

fire. When Brynhild opens her eyes, she knows Sigurd for the hero he is, and Sigurd knows that in the Valkyrie he has his match for courage and his master in wisdom.

When Sigurd becomes the Valkyrie’s lover, within the ring of fire, he learns what twenty lifetimes might never teach a mortal man. For in that embrace of love, many things in Sigurd are awakened and filled with the wisdom of the gods; while in Brynhild many things are put to sleep, and filled with the unknowing of mortals.

Sigurd, as the lover of the Valkyrie, knows that he must embrace strife and war, which give a warrior immortal fame. Painful as it is, Sigurd knows he must leave Brynhild and go out of the ring of fire into the world of men again, where he might earn glory enough to be worthy of his bride. This Sigurd resolves to do, but as a token of his eternal love and as a promise of his return, he places the Ring of Andvari - that all the world desired - upon Brynhild’s hand. While Brynhild sleeps, Sigurd rises at dawn, mounts Grani and passes out of the ring of fire.

When Brynhild wakes, she remembers nothing of Sigurd, or Odin, or any of her past before that day. Upon her hand is a gold ring, though she does not know its reason. All she knows is that she must await the coming of a warrior who knows no fear and can pass through the ring of fire. To this man, and this man alone, she will be sworn in marriage.

As for Sigurd, great though his love is for Brynhild, he knows that his fate is that of a warrior. Like his father, he has been chosen by Odin, and in his service Sigurd travels to many lands, and slays no less than five mighty kings in battle.

In time, Sigurd comes to the Rhinelands, which are ruled over by the King of the Nibelungs. The Nibelung King welcomes the now famous hero, Sigurd the Dragonslayer, with great warmth and friendship. In time, Sigurd and the king’s three sons - Gunnar, Hogni and Guttorm - become the closest of friends and allies in both war and peace. Sigurd and Gunnar swear unbreakable oaths of friendship, and become blood-brothers.

Seeing how Sigurd the Dragonslayer’s friendship has so increased the power and wealth of their realm, Gunnar’s mother Grimhild, the Queen of the Nibelungs, wishes to keep him within their realm. To this end, she hopes Sigurd might marry her daughter, the beautiful Gudrun. However, though she knows Gudrun loves Sigurd, she also knows Sigurd loves another.

Grimhild’s wish is not hopeless. For Queen of the Nibelungs though she is, Grimhild is also secretly a great witch capable of casting spells and making powerful potions. So in the feasting-hall one evening, Grimhild gives to Sigurd an enchanted drink. This potion robs Sigurd of his memory of the Valkyrie whom he swore to love always, and at the same time fills him with desire for the beautiful Gudrun.

Obedient to the spell, Sigurd soon asks for Gudrun’s hand and their marriage is blessed by all who lived in the Rhinelands. Many seasons pass, the royal couple are happy, and the power and glory of the Nibelungs grows and grows. Yet tales of a strange and beautiful maiden held captive in a ring of fire on a mountain reach the court. These tales mean nothing to Sigurd, but Gunnar wishes to win this maiden and make her his queen. His mother, Grimhild, is wary of this adventure and asks Sigurd to go with his blood-brother. Sigurd does this gladly, but Grimhild also gives to Sigurd a potion. By the potion’s power Sigurd may change his appearance to that of Gunnar.

Gunnar and Sigurd ride away and at last come to Hindfell and the mountain with the tower ringed in fire. Gunnar sets his spurs to his horse, but the beast turns away at each attempt, and the flames rear higher and more fiercely at every failure. Even though Sigurd lets him mount Grani, Gunnar gets nowhere.

Gunnar despairs at ever winning his queen, so he begs Sigurd to try in his place. Sigurd uses Grimhild’s potion and changes his appearance to that of Gunnar. He then mounts Grani and charges straight into the ring of fire. Sigurd’s boots catch fire and Grani’s mane and tail are alight. Horse and rider seem to hang in that inferno forever, deafened and blinded by its heat, but finally they pass through the flames.

Next is the barrier of the wall of shields, but as before, Sigurd shears through the iron wall with his sword. Behind this wall in the tower sits the beauty that is Brynhild all in white upon a crested throne, like a proud swan borne up on a foaming wave.

‘What man are you?’ asks Brynhild of the one standing before her. Memories of her past are gone from her mind, yet something deep within her tells her something is wrong.

‘My name is Gunnar the Nibelung,’ says the rider, ‘and I claim you as my queen.’ Passing through the ring of fire was the price of Brynhild’s hand, and she cannot refuse such a hero. Nor is there any reason for her to do so, for the man before her is handsome enough; and - by virtue of his deed - is brave beyond the measure of other mortals.

So does Brynhild embrace him and place her gold Ring of Andvari upon his hand to pledge her eternal love. Then within the tower she takes him to bed and lays with him for three nights, though these nights were strange to her. For each night the hero places his long sword on the bed between them. He must do this, he says, for he will not make love to his new queen until they both return to the great halls of the Nibelungs. In this way, the disguised Sigurd conspires, so he might not betray Gunnar and dishonour his bride.

When the marriage of Brynhild and Gunnar takes place in the hall of the Nibelungs, it is the true Gunnar who weds Brynhild and takes her to bed. In the land of the Nibelungs all seems content. But one day while bathing in a stream the two young queens set to quarrelling. Brynhild boasts that Gunnar is a greater man than Sigurd by virtue of his feat of passing through the ring of fire.

Gudrun will have none of this, for Sigurd has foolishly told to his wife the true tale of that adventure. So, the young queen cruelly reveals that truth to Brynhild; and as proof shows her the gold ring upon her hand. By this Brynhild is crushed, for this was the Ring Andvarinaut that she thought she had given to Gunnar that day on the mountain, but in fact Sigurd had taken and given to his own wife.

Now all the secrets are out, and poison runs in Brynhild’s heart when she learns of how she has been deceived. Outraged, she can only think of vengeance. Brynhild turns to Gunnar and his brothers Hogni and Guttorm. She taunts and threatens her husband.

‘All the people now laugh and say I have married a coward,’ mocks Brynhild. ‘And my disgrace is your disgrace, for they say not only did another man win your wife for you, but also took your place in the wedding bed. And no use is there to deny this, for the Ring of Andvari - which Sigurd gave your sister - is proof that this is so.’

‘Sigurd shall die, then. Or I shall,’ swears Gunnar. But he has neither the heart nor the courage to act himself, and slay his friend. Instead he and Hogni inflame the heart of their youngest brother, Guttorm, with promises and Grimhild’s potions to slay Sigurd. That night Guttorm creeps into the chamber where Sigurd lies sleeping in Gudrun’s arms. Young Guttorm thrusts his sword down with such force that it pierces the man and the bedstead too. Waking to death, Sigurd still finds strength enough to snatch up Gram and hurl it after his killer. The terrible sword in flight severs the youth in half as he reaches the door. Guttorm’s legs fall forward, but his torso drops back into the room.

When Brynhild hears Gudrun’s scream she laughs aloud, but there is no joy in her terrible revenge. For that night, Brynhild takes Sigurd’s sword and slays herself. True to her Valkyrie passion, she resolves that if she cannot be wed to Sigurd in life she will be wed to him in death. Once again and finally, Sigurd and Brynhild lie side by side - with Odin’s bright sword between them - as the fierce flames of their funeral pyre slowly devour them.

So ends the life of Sigurd the Dragonslayer, but this is not the end of the tale of the Ring of Andvari, nor of the Dwarf’s treasure. For the ring remains on Gudrun’s hand and the treasure is taken by her brothers Gunnar and Hogni, and hidden by them in a secret cavern in the River Rhine.

Gudrun is filled with horror at Sigurd’s death at the hands of her brothers, but she does not grieve long before her mother Grimhild comes to comfort her. Once again the old witch has prepared a potion, which secretly she gives to Gudrun to make her forget her grief, and the evil her brothers have done. Instead the potion fills her with love and loyalty to her brothers in all matters.

Still, Gunnar and Hogni wish to have Gudrun gone. They also wish to increase the power and glory of the Nibelungs, and believe they might do so by an alliance with the mighty Atli, the King of the Huns. And so, the brothers send Gudrun to Atli. Gudrun likes it not, but obeys and weds the King of the Huns and is his queen.

Now Atli the Hun is a powerful man, but one who is filled with greed. He has heard much of the huge treasure that Sigurd the Dragonslayer once won, and that the Nibelungs have taken this hoard by a foul murder. Each time Gudrun walks before Atli, her gold ring glints and Atli finds he can think of nothing else but that golden treasure.

Time passes and Gudrun gives the Hun King two young sons, but all the while Atli plans an intrigue and finally he acts. King Atli invites Gunnar and Hogni and all the Nibelung nobles to a great feast in his mead hall. But when the Nibelungs come to the feast hall, they soon discover that a huge army of Huns has surrounded them. The great feast hall becomes a slaughterhouse. Although the Nibelungs slay ten for everyone they lose, finally they are overwhelmed and all are murdered, save the brothers Gunnar and Hogni. These two are bound with chains and held captive.

The Hun King has Gunnar brought before him in chains, and promises to spare his life if he will give up the golden treasure that was taken from Sigurd the Volsung. But Gunnar says that he and Hogni have hidden the treasure in a secret cavern beneath the Rhine, and swore blood oaths that neither will reveal it while the other lives. At once Atli gives an order, and within the hour a soldier returns. In his hand is Hogni’s heart, which has been torn from his living breast.

Gunnar greets this loathsome act with cruel laughter. There had been no oath, he explains. Gunnar had been fearful that Hogni might surrender the treasure to save his life. But now that his brother is slain, only Gunnar knows the secret, and he will never surrender it. In rage, Atli has Gunnar bound and cast in a pit where serpents filled with venom finally still that warrior’s stubborn heart.

The Hun King’s wife, Queen Gudrun, is filled with grief at the death of her brothers and the obliteration of the Nibelungs. Although Andvari’s treasure is lost, Andvari’s ring still carries the Dwarf’s curse while it remains on Gudrun’s hand. And Gudrun - as the last of the Nibelungs - resolves to have bloody retribution for Atli’s treachery.

Though the battle with the Nibelungs cost Atli dearly and profited him little, the Hun King calls for a victory feast in his great hall. Secretly, Gudrun makes her preparations. She murders her own two children, Atli’s sons. From their skulls, she makes two cups. Their innocent blood she mixes with the wine; and their hearts and entrails she spits and roasts as his meat. All this she serves up to Atli at the feast.

Then late that night, Gudrun takes a knife and cuts the Hun King’s throat while he sleeps. She then creeps away, bars all the doors from without, and sets the Hun King’s great hall to the torch. This is the greatest pyre that has ever been seen in the land of the Huns, for all Atli’s soldiers and vassals perish in their sleep in that fire.

Before that inferno, Gudrun stands and stares with mounting madness, the flames bringing back many terrible memories. She flees the Hunlands and wanders until she comes to a high cliff overlooking the sea. She looks one more time at the glinting gold Ring of Andvari on her hand, then with a sigh she fills her apron with stones and leaps into the sea.

___________________________________________

*In earliest recorded sagas, the Nibelungs were called the Guikings. However, the names appear to be used interchangeably. Iceland’s Snorri Sturluson, in the thirteenth-century Younger Edda, states: ‘Gunnar and Hogni were called Nibelungcn or Guikings; therefore the gold is called the Nibelungen hoard.’ To minimize the confusion in view of later Germanic traditions, I will use the Nibelung name for the dynasty.