Part I: Identity and the System of Diversity

“The way we look at the world is the way we really are.”[1]

-Bob Dylan

1 Dylan as Jack Fate, in his film Masked and Anonymous (2003).

Part I: Identity and the System of Diversity

“The way we look at the world is the way we really are.”[1]

-Bob Dylan

1 Dylan as Jack Fate, in his film Masked and Anonymous (2003).

1. The Fixing of Identity

The creation of an identity implies the establishment of a difference... Every identity is relational and the affirmation of a difference is a pre-condition for the existence of any identity.[1]

-Chantal Mouffe, On the Political

Chantal Mouffe is a particularly interesting thinker on the left. Failing to find much inspiration from left-wing and liberal sources, she has looked to the ideas of Carl Schmitt, a powerful and controversial theorist of the right, on ‘the political’. As she says, ‘A key point of Schmitt’s approach is that, by showing that every consensus is based on acts of exclusion, it reveals the impossibility of a fully inclusive “rational” consensus.’[2] Establishing consensus means forming a group which shares it, and this means shutting out those who do not share it - excluding them from the space (the institution for example) in which the consensus has been established.

Looking at it this way, in a sense identity is politics, as the establishing of group boundaries. By identifying and demarcating the various groups that carry out political activity, we politicise them and the people within them - and divide them off from others. There is no ‘I am’ without a ‘you are’ and a ‘he/she/it is’; there can be no ‘us’ without a ‘them’. By defining what is ‘left-wing’ and what is not from a left-wing perspective, we draw a group boundary which separates off ‘our’ people from ‘them’; or if we take it a step further, friends from enemies. Likewise, by emphasising racial differences, we do not just politicise the racial group we are seeking to politicise, but also those outside that group (both in our consciousness and in theirs if and when they overhear us). When we uphold the importance of a particular religion in public, we raise the consciousness not just of those who share that religion but also of those that do not.

Identity unavoidably relates itself to other identities in this way, by establishing differences and contrasts. Gay makes sense only in relation to straight. Black makes sense only in relation to white. Socialism only makes sense in contrast to alternatives like conservatism and liberalism. Consider some of the identity conflicts of recent history: from Sunni and Shi’a Muslims, to Republicans and Unionists in Northern Island, Hutu and Tutsi in Rwanda, and any number of poisonous football-related rivalries in Britain. The active motion to each of these conflicts is provided by separate identities feeding off each other for sustenance and fulfilment. One side could not exist without the other, and the oppositional aspect prevails over any intrinsic meaning the groupings may have.

All this does not mean that identity is a bad thing anymore than that life is a bad thing. The point is rather that an identity is formed as much by what it is definitely not as much as what it is. Indeed what it is is largely circumscribed by what it is not. Opposition and difference are integral to identity, and that goes for the liberal-left with all its talk of inclusion as much as any of the fixed identity groups.

From the perspective of Labour people and other left-wingers, the Conservatives and UKIP especially offer crucial reference points which help define who and what we are, by telling us what we are not. Likewise the Daily Mail, Express, Sun and other Murdoch-owned newspapers: by asserting what they are, they help us to draw the boundaries of who we are. We set our moral compass according to that of our opponents. This is not an entirely healthy situation you might say, and certainly contributes to the Culture Wars that rage in our public life. But this is how identities establish and maintain themselves. Once the ground is prepared and the opposing forces are established behind their lines, then the conflicts characteristic of politics can work themselves out.

This is all contrary to regarding identity as some sort of inalienable ‘thing’ or fixed aspect of us, somehow defining who we really are. As Mouffe puts it, ‘every identity is relational.’ We are much better off looking at it as an activity or process, of binding ourselves into the world around us. Identity politics as we know it, both now and historically, binds people into the world using this idea of identity as fixed, mobilising properties like skin colour, gender and class and claiming a sort of literal ‘identity’ between people and these things. But this requires some sort of binding process: it requires the politics of identity itself to achieve this form of identity. We can bind ourselves (and be bound by others) through all sorts of things: through shared nationality and locality, through shared interests, values, experiences and politics. But we are also bound simply by living and growing up where we live and grow up, which gives us a commonality of experience and through that a form of identity.

Identity as a binding process therefore has different forms, some of which are grounded simply in being somewhere but others in which thought and assertion have a part to play. Here we will delineate four general types:

These four forms are not mutually exclusive. They can all battle with each other and coexist in each of us over time; indeed we can fall in and out of them rather as we fall in and out of different moods, with the possible exception of category 4, identity as a choosing to choose, which requires a certain type of effort on our part.

So what are these different forms of identity all about? Let us look at each of them in turn.

Except for the first category of unreflecting, basic identity, these forms all entail in some way taking a stand on identity, even if it means ceding one’s agency and responsibility by choosing not to choose and going along with whatever form of administration is dominant. By taking a stand or assigning away the responsibility for taking a stand, each of these forms participates in the machinations of power.

Going along with assertion and administration is conformity, so the assertion and administration that secures it has secured a form of social and political power. Without the co-dependence of these two forms of identity, systems of identity politics - and indeed most political activity - could not function.

The philosopher Martin Heidegger shed some light on what we are calling ‘administration’ in Being and Time. He wrote:

It can, as it were, take away ‘care’ from the other and put itself in his position in concern: it can leap in for him. This kind of solicitude takes over for the other that with which he is to concern himself. The other is thus thrown out of his own position; he steps back so that afterwards, when the matter has been attended to, he can either take it over as something finished and at his disposal, or disburden himself of it completely. In such solicitude the other can become one who is dominated and dependent, even if this domination is a tacit one and remains hidden from him...[3]

In this process of administration, the ‘others’ who are being administrated to can either take over and administrate what is administrated to them afterwards or ‘disburden’ themselves of it altogether. Disburdening is making-way: letting whatever administration is being applied dominate in your existential space and not making any challenge to it. However, in this passage Heidegger does not address the possibility of rejection, of us not giving way to become dominated and dependent, of rejecting assertions and administrations about how we should behave. Rejection comes relatively easily if the existential environment around us does not align to what these others are trying to enforce on us. But if the administration does align with our existing connections, then the prospect of rejection immediately appears problematic, as something to be avoided for the sake of convenience and familiarity. Looked at it from this perspective, submitting to administrated, asserted identity involves at least an element of choosing not to choose, of bowing to existing authority or at least not resisting it.

An introduction to fixed identity

When we look at fixed identity literally, as a relation between people and their skin colour, gender, ethnicity, sexuality and even religion (in the sense of being fixed into it), it can seem startlingly empty. These properties or identifiers have limited meaning in themselves and the idea that who we are is somehow contained in them can seem baffling. It is obviously true that I have the skin colour and sex/gender that I have and this helps to define me and differentiate me from others. There is a literal identity there, between one thing and another. But it is not an identity that stretches very far. There is little meaning or guidance to be found in it, in itself. Abstracted from the additional meanings we add to it, this sort of identity has virtually no content and can do little to guide us on good and bad, truth and falsity, and how to live.

In this way there must be an effort to assign meaning in order for fixed identity to take a significant role in our lives. What is already fixed about identity is not enough; it needs something more. It needs to be fixed to something outside itself, out in the world. But in order for fixed identity to remain fixed and nailed down as my skin colour or gender are then those relations to the world must be fixed and nailed down too, which means nailing down the world as fundamentally unchanging. We can see ideologues of identity and diversity doing this by fixing the favoured identity groups to relations of victimhood and oppression which are not individual in character but universal, societal, structural and systemic - fundamental and unchanging. The fixedness of fixed identity appears in those relations-as universal victimhood and oppression - as much as in the actually fixed (or quasi-fixed) physical characteristics or identifiers.

Identity based solely on the universality and inevitability of victimisation and oppression is a pretty grim prospect though. There is little there for someone to feel good about and likewise little to guide them in how to live. Identities need proper cultural forms for people to latch on to and appropriate with some sort of purchase on their desires, connecting into the world in a more promising way than the oppression story would have it, offering attractive possibilities rather than just the prospect of unrelenting victimhood.

However, contrary to the liberal-capitalist fantasy of a world of unlimited choice, there are limited cultural forms out there to latch on to. Moreover, to appear credible, identities based on fixed properties like skin colour and gender must be shared in reality by people who possess those fixed properties - and not by those who do not. A positive black identity must be an identity based on an actual existing culture of black people (and not of non-black people). A positive Muslim identity must be attached to actual existing Muslim culture in the world, distinguishing Muslims from non-Muslims. (This is one reason why feminist politics struggles to gain much purchase with women as a broad grouping, for it is difficult to demarcate women’s and men’s culture without demarcating women and men).

As the British-born American academic Kwame Anthony Appiah has put it:

The large collective identities that call for recognition come with notions of how a proper person of that kind behaves: it is not that there is one way that gays or blacks should behave, but that there are gay and black modes of behaviour. These notions provide loose norms or models, which play a role in shaping the life plans of those who make these collective identities central to their individual identities. Collective identities, in short, provide what we might call scripts: narratives that people can use in shaping their life plans and in telling their life stories.[4]

These modes give necessary meaning to identities: of something to fit into which a narrative of victimhood alone cannot offer. The literal identity of the basic identity markers like ‘black’, ‘white’, ‘Muslim’ and ‘gay’ are thereby expanded to incorporate certain cultural practices brought in to represent them. So for example American hip-hop culture has come to represent ‘black’, while the clothing and religious practices of a relatively small sect in the Arabian Peninsula have come to define devout Muslims. Identity politics demands we attach the bare facts of skin colour, gender and religion etc. to the specific cultural forms which it politicises as belonging with those bare facts. In this way, identity connections with little intrinsic meaning gather positive meaning and become attached to real possibilities in the world.

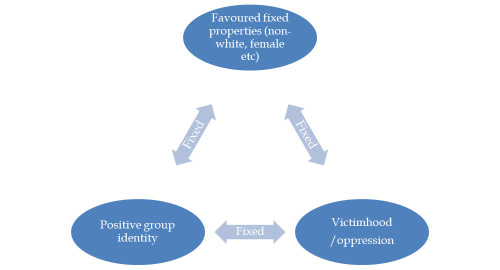

We might see from the diagram below how this process of fixing works in practice. One connection links the favoured properties or identifiers of identity to victimhood, so fixing them to that, while another fixes them to forms of positive identity. In turn, this links the positive identity to victimhood, thereby attaching forms of culture with victimhood, not just the fixed identifiers.

Fixed Identity: locking it in

But why do some cultural forms come to triumph in becoming related to fixed identity? The old alliance of money and power certainly plays a role. For, far from challenging dominant cultural forms, forms of identity politics constantly find themselves allying with powerful existing forces in the world - hence the conservative forms it takes, contrary to the progressive ethos of the ideology of diversity. But also for forms of politics which aggressively promote ‘us’ and ‘them’ relationships between fixed identity groups, it helps to have as content antagonistic cultural forms which draw clear dividing lines and are unpopular with out-groups. Appearing as ‘extreme’ to out-group members helps to maintain the distinction between insiders and outsiders while also generating opposition from the out-group which feed back to bolster group solidarity and any victim narrative being asserted, accommodating them to the necessary victimhood story.

As an example, the former Islamist activist Ed Husain has written about traditional Arab dress becoming more prevalent among British Muslims:

Socially, there is the rise of children at primary schools across the capital wearing hijab, or headscarves. This is a sign of separatism, a desire to assert difference from other children decided by parents. I see niqabs or face-covers for women, and British Asian Muslim men wearing Arab clothes that our visitors from the Gulf readily discard. How did we become silent at this physical changing of our city’s face?

Politically, being visibly Muslim is fast becoming a statement of rebellion.[5]

In practice, this is how politics works, by dragging groups away from each other and stoking up opposition between them, which then feeds back to re-energise the politics. It also goes to show how fixed identity in practice is anything but. To fix it in place and maintain it as fixed requires action; it needs to be politicised, with constant effort to keep relations to the victimhood story and versions of positive identity in place. Far from simply showing knowledge of how things are, placing emphasis on fixed identity is a political act. Like all forms of identity, it needs relating in order to be related, but it also needs submission or giving-way for the relation to be secured.

We might see how identity politics - which are generally intended to fight oppression - can be pretty oppressive themselves. They lock people up in antagonistic relations to the world and seek to enforce certain cultures on them under the guise of being there already. As Professor Appiah has written, ‘Demanding respect for people as blacks and as gays requires that there are some scripts that go with being an African-American or having same-sex desires. There will be proper ways of being black and gay, there will be expectations to be met, demands will be made. It is at this point that someone who takes autonomy seriously will ask whether we have not replaced one tyranny with another.’[6]

The power of fixed identity

Identities need social and political support in order to flourish, helping giving-way to take place without resistance or even much need for thought. This support manifests itself through connections which bind the identity into place in the world. Through these connections, some identities capture and hold political space and others do not. Those that succeed do so not on account of being somehow right or wrong but because of being locked in to a network of connections and finding more ready acceptance because of them. This means being aligned with existing social powers in some significant, meaningful sense.

In our world, the politics of fixed identity is one of the dominant forms of politics in our public life - and is if anything growing in importance. The importance and even dominance of fixed identity politics has a great many factors to it: secured access to the public sphere, powerful institutional forces to promote it and of course enough ‘ordinary’ people out there to accept and spread it themselves.

Fixed identity and the liberal-left

But what gets so many people - and influential people in senior positions in some of our most important institutions - to accept and propagate these narratives of fixed identity? Without a doubt a great many genuinely believe or have at least accepted the stories about universal victimhood and oppression of the favoured identity groups, and disregard any role that positive identities might have in perpetuating social differences and inequalities. Historically, and to an extent today, there is some good reason for this. But there is a lot more to the phenomenon than that.

The acceptance of oppression and victimhood as universal is crucial here in taking us on to a higher plain of knowledge, offering absolute, universal explanations for what is going on in the world around us. It reveals a world that is already known.

In order to fulfil their role presiding over the system of diversity, liberal-left administrators of diversity must accept these stories; fitting into the system and accessing its possibilities requires it. But this means accepting or at least not questioning that fixed identities are fixed into the world - and therefore that the world itself is fixed. This a priori (or, you might say ‘prejudiced’) knowledge is a fundamental knowledge of how things are - but it does not need to be explored in order to be adopted. It simply needs to be taken on board as assumption in order to fit in with others who have done the same and institutions which promote the same narrative, thereby embedding itself as a form of personal identity - liberal-left identity.

Taking the stories of oppression and victimhood on board as knowledge or assumption makes an issue of a different kind of identity: the fixed identity of the groups who are subject to that oppression and victimhood (and also to an extent that of groups who are not subject to it and might be seen as perpetrators of it). This framework and the ideological background provides great interpretive power, allowing members to interpret pretty much anything going on in the world in terms of this universal knowledge of how power relations work between the different favoured and unfavoured fixed identity groups. Systems of ideology like this are internally coherent and self-enclosed; facts and values are united. There is no need for any outside influences. The world stands revealed already.

Employing this framework of ideology while presiding over the system of diversity, the progressive liberal-left gathers political strength for itself, for the system and the ideology, by embedding narratives of fixed identity into public discourse and institutional life. A liberal-left identity that is not fixed to its members’ physical characteristics plays a major role in fixing other people’s identities to their physical characteristics, or making non-physical characteristics appear fixed in the same way. The former form of identity presides over the submission of others to the latter. For the favoured fixed identity groups, submitting to fixed identity entails bowing to a social power that treats them as pre-determined in who they are, so not just submitting to administration but to the necessity of submission to this form of identity.

But, just like these fixed identities that it makes an issue of, the liberal-left form of identity requires constant reinforcement through administration and giving-way by its members. Ideology provides a tool enabling this to continue on without recourse to much thought and doubt - a great strength in political activity. But this tool is available to anyone - anyone can administrate it as much as they can hear it. The relations of authority here are not such that some act and others are acted upon, like subjects and objects. Rather, everyone is acted upon, while our own assertion, administration and acceptance help keep the whole show on the road. Writers, politicians, celebrities and activists take a more prominent role than others, but the extent to which identities and ideologies originate with these people is questionable. They may be influential, but they operate in a similar way to the rest of us: policing the boundaries of what it means to be left-wing or liberal, or what it means to be black, female, gay or Muslim, but just on a grander scale with many more connections into the world.

Administrating consensus

The role that these public figures fulfil is rather like that of senior administrators or managers: administrating and maintaining a pre-agreed consensus; passing the word down; keeping the show on the road; telling the folks what they need to hear. It is not a role like that of a leader, chairman or chief executive who evaluates strategy with the freedom to choose new ways to proceed. New opinion and pathways of identity are not generated by these people; they can only clarify existing opinion and identity, and apply it to new situations. Indeed a key part of the role of administrator is to not shake things up and come up with anything new. It is inherently conservative, gaining authority by ceding control to existing authority. Administrators only carry authority so much as they do not challenge it, thereby maintaining their own identity with the group.

So we might see how administrators of identity must submit to authority if anything more intensely than those they are administrating to, since they are most visible and therefore most exposed to attack for ‘wrong-think’. Ultimate authority is not vested with them but is rather in the system of connections; all must conform in order to remain connected. Heidegger used the German phrase ‘Das Man’ to describe how this sort of thing works, which probably translates best as ‘the one’ (as with the passive ‘one is’ or ‘one does’ - suggesting something diffuse, with no ultimate centre or source). ‘The one’ is something which exists ‘out there’ but also ‘in here’. We might say it is manifested in ‘group-think’: the general understandings and opinions which become established in the echo chambers of everyday discourse.

Heidegger said of ‘the one’:

We take pleasure and enjoy ourselves as one takes pleasure; we read, see, and judge about literature and art as one sees and judges; likewise we shrink back from the ‘great mass’ as one shrinks back; we find ‘shocking’ what one finds shocking. The “one”, which is nothing definite, and which all are, though not as the sum, prescribes the kind of being of everydayness.[7]

He added:

It can be answerable for everything most easily, because it is not someone who needs to vouch for anything. It ‘was’ always the “one” who did it, and yet it can be said that it has been ‘no one’. In [our] everydayness the agency through which most things come about is one of which we must say that “it was no one”.[8]

‘The one’ that Heidegger talks about in these passages helps to merge opinion and understanding into a generalised consensus of shared understandings. But for most people certainly now and probably in Heidegger’s day too it does not make much sense to talk about a single ‘the one’ so much as many different ones: all mixed up with, fighting against and allying with each other in various ways at various times. The strength of fixed identity in our world today is that it has several ‘ones’ or identities working in concert on its behalf, combining and cooperating with each other through a whole network of connections which help to bind each other into place.

In this way the fixed relations of the system of diversity help fix fixed identity into place in the real world. There is still agency going on here though, as is implicit in the ever-present possibility of people resisting the consensus and choosing not to administrate or abide by it, which would entail some sort of social breakdown and loss of identity - and a corresponding threat to the system as a whole. The action of the system and its various forms of administration must therefore be constant and wide-ranging in order to prevent these breakdowns from occurring.

When successful, identity offers protection and relief from uncertainty, anxiety and potential social isolation, providing relations and reference points to ease our existence in the world. This may burst the idea of autonomy somewhat but it does at least provide us with existential security and safety in numbers, including senior administrators in place to speak on our behalf while we are busy doing other things. With a secure identity like this, we have access to shared language, social roles, recognition from institutions and some sort of value system - all of them pre-approved and promising social approval.

Without these things, identity can have little purchase. It must offer convenience and possibilities for those who conform while holding out the prospect of discomfort and isolation for those who do not. For the favoured fixed identity groups in the system of diversity, this means going along with their respective fixed identities. For members of unfavoured groups (like men, white people and heterosexuals), aligning with the system requires attaching oneself to any favoured attributes one has, and/or joining the administration of diversity. The penalty for not doing either is exclusion from the system and its possibilities altogether. Identity is still available to us through the system of diversity even if we do not fit into any of the favoured groups - just as long as we are prepared to take on liberal-left identity.[9]

This is a crucial aspect of the system’s power, that it offers possibilities and belonging not just to favoured group members and their representatives but to unfavoured group members - and like the fixed identity groups it pulls them in with the prospect of existential security, belonging and social approval. The system is there, available to us. We can plug into it and gain immediate recognition by making-way for it. Failure to do so means being denied the connections it offers. The system of diversity is a system of relations - and relations create possibilities, habits, set ways of doing things - and with all that, convenience. Identity lets us fall into its embrace rather than demanding we say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and declare allegiance to it.

If we reject identity, we need to find something else, alternative connections and ways of understanding ourselves and how we should interact with the world. These alternatives may not be available, be unattractive and/or be in the process of dying out. The contrast in strength with the liberal-left and fixed identity groups in the system can look stark. After all, they have their ideologies mapped out already, a ready-made body of knowledge integrated with morality and already put into language, available to use, providing the home comforts of identity through something which is already there, known and familiar. Ideologies, including religious ones, give us the comfort that we do not need to ponder anything further, which is mightily convenient. Since we are unable to pay close attention to what is going on most of the time, the reassurance that everything is covered already and we need not bother ourselves trying to figure out what is going on offers blessed relief. Ideology integrates itself nicely into our familiar life like this, becoming another plank of identity along the same lines as what we eat and the way we dress; its versions of truth versus falsity and good versus bad become subsumed into everyday life and habit and pass beyond the realm of serious questioning.

As Heidegger put it in his language, ‘For the “one”... the situation is essentially something that has been closed off. The “one” knows only the “general situation” [and] loses itself in those “opportunities” which are closest to it...’[10] We fall into identity and become enveloped by it as much as we choose it.

This contrast between ‘the situation’ and a ‘general situation’ is one between reality as it manifests itself and reality as presumed and assumed in advance. The ‘one’ presumes and assumes the nature of the situation, thereby prescribing a ‘general situation’. Ideology provides all-encompassing theory to back this up and explain anything that comes along. Even if we do not have it at our own fingertips, we know it is there, offering authority through a fixed body of knowledge of a fixed, unchanging world. It has been worked out in advance and can be used to interpret any actual situation existing in the world. For liberal-left identity and specific ideologies of identity the general situation is that of victimhood suffered by certain identity groups. To fit into the system, the identities of those victim groups must conform to this account of victimhood, so must be prescribed and controlled by administrators in this way.

All of this fits well into bureaucratic systems and into the habits of bureaucracy. For the idea that what is important and most relevant about us is a consequence of our skin colour, gender, religion and sexuality allows straightforward measurement by a politician or bureaucrat sitting in an office with a spreadsheet, allowing them to discern how privileged or disadvantaged we are and how much favour or disfavour we deserve without having to know anything more about us. Ideology and bureaucracy form an easy connection like this.

Habit, conformity and the existing connections of the system - including into bureaucracy - serve as a sort of glue, keeping the different identity groups in place, from the liberal-left administrators of diversity to the favoured identity groups and even the unfavoured groups, who by standing outside the system provide its natural opposition. This all adds up to a form of status quo, with stable relations within groups, between group members and institutions, and across the different levels of the system. All of this serves to maintain the power of those people: the administrators of diversity who preside over the system and the favoured group representatives who preside over the various favoured identity groups.

1 Chantal Mouffe, On the Political (Routledge, 2005), p. 15.

2 Ibid., p. 11.

3 Heidegger, Being and Time (HarperPerennial, 2008, 1962, 1926, trans. Macquarrie and Robinson), p. 158, with slight changes to the translation as suggested by Hubert Dreyfus in Philosophy 185 lecture course, Fall 2007, UC Berkeley.

4 K. Anthony Appiah: ‘Identity, Authenticity, Survival: Multicultural Societies and Social Reproduction’, in Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition by Charles Taylor et al. (ed. Amy Guttmann, Princeton, 1994), pp. 159–60.

5 ‘Ed Husain: Muslim Londoners must stand against hatred’, Evening Standard, 11th August 2014.

6 Appiah, in Taylor et al., pp. 162–4.

7 Heidegger, Being and Time, p. 164.

8 Ibid., p. 165.

9 There is a contradiction here in that the only way that unfavoured, oppressor identities can fit into the system is by presiding over it, taking a sort of governance role over the favoured, oppressed groups.

10 Ibid., p. 346.

2. The Tribe: The Liberal-Left as an Identity Group

As an identity, liberal-left identity makes an issue of fixed and quasi-fixed properties of identity like skin colour, gender and religion. Moreover, it makes an issue of them on behalf of others. The progressive liberal-left fits into the system of diversity by presiding over it, overseeing formal and informal favouritism towards the favoured fixed identity groups in the system. It is an active identity, assigning passive identity to others - and assigning significance to this fixed identity above and beyond pretty much anything else.

However, although the liberal-left as an identity group is concerned with fixed identity, it is not much concerned with the content of the fixed identities it favours, except in so much as they are identities of victimhood. Rather, it offers protection to them, including by non-interference, which means outsourcing control of ethics, values and cultural practices to the de facto leaders of these groups. In relation to unfavoured identity groups, by contrast, it is constantly interfering: criticising, demanding and dictating what can be said and what should be done.

We might see how being a ‘proper’ member of the liberal-left does not come from having the correct fixed identity but from holding the correct views on identity in terms of the identity of others, or at least in not resisting these correct views. In political if not theoretical terms, this means accepting the status of favoured group members as victims attached to their victimhood and in need of special protection from a hostile world. This protection manifests itself especially through the priority given to countering racism, sexism, Islamophobia and homophobia as threats to the favoured groups. From centrists including New Labour types and Liberal Democrats, to the far left of Momentum and the Green Party, this primary agenda unites all strands of the political left. As a wider liberal-left, this is what we are and what we do. The administration of diversity largely constitutes the liberal-left.

On the surface, this seems absolutely fine and good. However, the system of diversity fixes the relations between different groups as universal so does not address them as phenomena, but establishes the whole of society as a racist and sexist structure and system which carries these various ‘isms’ and ‘phobias’ as a core part of what it is, at all times and in all places. Because the structure of society touches on everything in the world, everything we do not like in the world can be seen as a consequence of it. This frees us to attach racism and sexism for example to anything and anyone we like. It can also mean treating the world as a sort of enemy.

In this way anti-racism, for example, has become a stance to approach the world in general rather than a stance adopted solely in response to racism. It has broken the bounds of phenomena and become a whole way of looking at the world, one for which racism is universal, underlying everything and always present. The same goes for sexism, homophobia and Islamophobia: we assume their existence prior to their existence. In situations where they are not occurring, we nevertheless use them to shed light on what is happening. We step in even when there is no reason to step in. We defend even when no one needs defending. We attack and hound out of their jobs even those who have done little or nothing wrong.

As a result we might see how terms like racism, sexism, homophobia and Islamophobia have evolved in meaning so that they refer not just so much to individual behaviour (or ethics, involving choices) as to the whole of society as a system. This system is deterministic in character and is ever-present and inescapable, with unfavoured identity group members existing in a state of original guilt. Meanwhile, the ‘universal values’ of the liberal-left like equality, social justice, tolerance and diversity have evolved in meaning to fit this fixed structure in which they find themselves. This has happened in such a way that they have quietly lost their universality in everyday usage and come to align specifically with the system’s various group favouritisms. (We explore this in Chapter 7, on the Control of Language.)

By relentlessly asserting or at least assuming relations of structural oppression and universal victimhood between oppressor and oppressed identities, the administration of diversity focuses the liberal-left’s attention, narrowing down to certain forms of reality while at least implicitly rejecting and excluding other forms which might contradict them (like an absence of racism in certain situations for example). The institutional architecture of the liberal-left reflects this focusing and narrowing, with groups and organisations projecting these forms of identity politics into the world, capturing political space with them and blocking off alternative possibilities (this is something we look at in Chapter 5, on the role of institutions).

From the fixing of fixed identity into structures of societal oppression and into the system of diversity itself to the fixing of language, there is a lot of controlling going on here. This is the nature of liberal-left identity: it sits at the apex of the system of diversity, overseeing and managing it. From this overseeing position it administers forms of favouritism and patronage which keep some of the groups to be favoured at arm’s length, mediating these relationships through group or community leaders who have taken on the role of representation and are largely left alone to do so.

Mass immigration: A cause to gather around

The subject of mass immigration probably brings out liberal-left identity and its ideology of diversity in the clearest form. It is unthinkable that the system of diversity could have arisen and developed to anywhere near the degree it has without mass immigration. This defining phenomenon of our times has not just brought in large numbers of people who can be funnelled into the race-based identity groups within the system. It has also offered possibilities to various different groups in British government and political circles, which have gathered around immigration and immigrants as a cause; for them, mass immigration has offered a role and an ongoing project to oversee and enforce. We might identify three broad political tendencies which have come together over this cause:

i) Post-imperial administration

As David Goodhart has shown in his book, The British Dream: Successes and Failures of Post-War Immigration, the model of administration and representation we see now in the system of diversity has more than a little in common with the way Britain managed its colonies in the days of Empire.

Goodhart says,

Britain ruled most of its colonial territories with a relatively light touch, dividing and ruling and often governing indirectly through local elites, like Nigerian emirs and Indian maharajahs... In today’s language we would say that British colonialism embraced ‘difference’, albeit in the context of a hierarchy that places white Europeans at the top.[1]

The figure of the colonial administrator, presiding over, accepting representations from and giving favours to various different groups under his purview, has a lot in common with contemporary administration of multiculturalism and diversity. For a start it is an elite role; it oversees and directs its politics through group or tribal leaders, giving them access to higher power. It also stands apart, not interfering with the representatives’ relationships to their group members, thereby outsourcing power over what is good and bad within those groups and conferring political power on to the representatives it favours.

As the first waves of mass immigration came in from former Empire countries, colonial-style multiculturalism effectively allowed Britain’s governing elites to pick up where they had left off in the Empire - slipping into old ways that were familiar to both administrators and many of the immigrants themselves. Goodhart says that ‘in the 1960s this translated easily into the cosmopolitan manners of a new liberal elite too - allegiance was now to tolerance and openness instead of the monarch, to England’s “genius” for multiculturalism.’ He adds: ‘The core members of this new elite, according to [the sociologist] Geoff Dench, were “policy-makers and the public servants responsible for carrying out social policy but it extends widely into the educational establishment and liberal professions... and their role is to stand impartially above and integrate different elements of the population.” This is what both imperial and multicultural elites do.’[2]

In this way, mass immigration offered opportunities to a British administrative elite keen to continue its role civilising the world’s population, albeit now mostly within the confines of Britain (though also in the rest of Europe over time, through the European Union).

ii) The radical left

The overseeing, presiding perspective of liberal administration overlaps to a great extent with that of the mostly middle class, university-educated elements of the political left who found a new victim class to support as a result of mass immigration from the former Empire countries - and through that a renewed sense of mission. These incomers had suffered the iniquities and injustices of British colonialism and were now confronted with racism and anti-immigrant feeling on arrival in Britain - so they attracted natural sympathy from decent people.

The political left already had an established body of Marxist and post-Marxist theory to hand concerning an oppressed class overcoming its oppression and opening the way to salvation for all mankind. Previously, these theories had looked towards the ‘proletariat’ or working classes to fulfil this historical role, but the working classes had failed to behave as they were meant to. These new people coming in promised a fresh start for the left: a new class to sponsor, raise up and pin one’s hopes for renewal on. So, while the left turned its sympathy and affiliation to immigrants and their descendents, it turned away from the old white working class it had previously sponsored (and which had widely resisted the immigrant influx, sometimes in a decidedly unpleasant way). In doing this they found common ground with liberal elitists who looked down on the same people. Out of this combination of top-level power and ideological commitment brought by these two tendencies, we might see our present ‘liberal-left’ being born and our system of diversity established.

iii) The economistic tendency

But the alliance for mass immigration has a significant additional wing to it, brought in by the constant expansionary pressures of capitalism to increase consumption, production and competition - and which a rapidly rising and diverse population feeds in to. For many business and asset owners, the unprecedented numbers of immigrants coming in have turned out to be a useful if not essential tool for expansion - increasing competition in the economy, bringing down business costs and also raising returns from property ownership due to increased demand. By boosting consumption, an expanding population increases economic activity, which in turn allows governments to report robust economic growth and give the impression they are doing a good job. In this way mass immigration can appear as a great way to maximise economic activity without the economic administrators actually having to do very much except let the population grow. It is like a project but where the project costs are defrayed elsewhere, on to other government departments and on to the cost of housing for example.

These three different political tendencies have come to fuse through liberal-left identity, helped by each of them taking a similar overseeing, controlling stance towards society and the state - the first’s source being in actual power and the other two having their sources in ideology as well as political power. They have helped to maintain a broad and formidable coalition in favour of continual mass immigration, one which covers most of organised politics in Britain and encompasses not just the broader liberal-left but also powerful forces on the right. It stretches all the way from free market ideologues, our big business elite and ‘progressive’ Conservatives like David Cameron and George Osborne, through the Liberal Democrats and the ‘moderate’ wing of the Labour Party to the SNP, Greens, Plaid Cymru, the far left of Labour (including Jeremy Corbyn) and the rest of the anti-capitalist, anti-Western activist left - plus a large bunch of vocal campaigning groups. Even though polling has shown half to three quarters of the population disagrees with it, this motley crew has enough clout to win most political battles in Britain, and indeed has conclusively won the political battle over mass immigration up until now.[3]

From the liberal-left side of this coalition, we can see the strength of feeling from polling of Labour Party members, with around 80 per cent supporting mass immigration according to research conducted in July 2015 - roughly the opposite spread as the general public at that time.[4] Yet this contrast is often celebrated, with commentators and others taking pride in their superior understanding compared to the ignorant masses. This is the pride of a social class as much as anything, fitting snugly into a new version of the very old British class system.

The fusing and gathering of these different political perspectives around the same aim and the same people is what gives the coalition its power. Gathering together gives each of them extra political power and a broader suite of arguments to make their case, so that the free market right now finds itself boasting about diversity, while the left has got used to repeating how immigration and immigrants are good for the economy. As a result, despite its relatively small support in the country, its messages are a constant presence in our public life, appearing as a dominant, consensus view to be defended rather than as a minority perspective struggling to gain attention.

The liberal, cosmopolitan dream

The confluence of these forces creates openings and opportunities for people and institutions to push these narratives and feed off the political power invested in them. A classic in this genre was written by Jeremy Cliffe of The Economist for the centre-left think tank Policy Network, entitled, Britain’s cosmopolitan future. How the country is changing and why its politicians must respond. Cliffe’s own career progression has been meteoric: from First Class degree at Oxford to Harvard Fellowship, working for the Party of European Socialists in the European Parliament and for Labour’s Chuka Umunna in Britain, he has since gone on to be UK Politics correspondent at The Economist and then taking the prestigious ‘Bagehot’ by-line - all in the space of a few years. If we are looking for the confluence of leftist, economistic and elite forces in contemporary public life (or indeed for the ‘liberal’ or ‘metropolitan’ elite or Establishment), he is not a bad place to start.[5]

In common with that confluence of forces, Cliffe’s paper sketches out a picture of a sort of liberal cosmopolitan utopia coming upon us, in which Britain and its people are being transformed by the rapid influx and spread of immigrants and their descendents. It is a remarkably confident and unequivocal thesis, prescribing the future he wants to see as something which will be: of how ‘cosmopolitanism is Britain’s future’ and that his ‘hyper-liberal vision... resembles the future’.[6] He talks of how political parties need to embrace this future, instructing them that, ‘A cosmopolitan politics is not just electorally advisable. It is progressive, liberating and good for Britain.’[7]

To exemplify his historical vision, Cliffe picks out one of the segments from film-maker Danny Boyle’s London Olympics Opening Ceremony of 2012. What caught his imagination was not the stunning Pandemonium sequence depicting Britain’s traumatic transformation from rural society into industrial powerhouse, but the one focusing on British popular music and culture - centred on the relationship between a pair of young dancers who were, crucially in political terms, of black skin and mixed race. Cliffe describes this sequence as ‘a vision of the country in all its contemporary modernity’, saying, ‘The picture is one of a young, urban, multi-coloured, technological, consumerist, permissive Britain at ease with itself and in the modern world.’ He quotes approvingly Jonathan Freedland of The Guardian calling the sequence, ‘a shorthand for a new kind of patriotism that does not lament a vanished Britain but loves the country that has changed’.[8]

For a large, loud and brash but otherwise unremarkable part of the ceremony, Cliffe and Freedland invest many hopes and dreams in it. These are all hopes and dreams of change - as we have seen, of a ‘Britain at ease with itself and in the modern world’ and ‘a new kind of patriotism’, both associated with forgetting and disregarding the past (‘a vanished Britain’) and instead embracing ‘contemporary modernity’ as ‘young, urban, multi-coloured, technological, consumerist, permissive’. This is about loving the elements of the country that have changed and pushing into the past those that have not, showing a preference for the new above the established and enduring - including a preference for newcomers and young people over older people and those with long-established ties in the country.

In this vision we might see a soft version of the attempts to wipe out historical memory that many Marxist movements have engaged in, but also a yearning to imitate the North American experience so that Britain’s history before mass immigration might appear as a sort of ‘pre-history’ just like North America’s before the arrival of European settlers. For this sort of outlook, there is no good to be found in the past; the only good to be found is in the brave new future it sets out. It is a vision of the world’s people uniting in Britain under the wing of liberal cosmopolitanism, finding a new patriotism by ditching all elements of the old versions, disconnecting ourselves from the country’s past and everything in it while ‘embracing’ the future as something better by definition.

The utopianism here is at times quite startling. As Cliffe puts it, ‘The ceremony embodied not just the country that has changed but the one that is still changing; the one in which people are becoming more relaxed in a churning world of difference and diversity, less rooted (perhaps even less sentimental), simultaneously more at home in the mass and more truly themselves.’ He adds:

The Britons [the ceremony] describes are indeed slipping their institutional, ethnic, geographical and social moorings. This change expresses itself in a number of trends: the growing comfortableness in an ethnically diverse society, the live-and-let-live attitudes of young Britons, the new self-confidence and swagger about Britain’s cities. Some disparage these with the term ‘metropolitan’. Others go with ‘liberal’ or even ‘libertarian’. But no word quite captures the sum of the changes convulsing and deracinating the country as neatly as ‘cosmopolitan’.[9]

In his story, Cliffe associates Britons being ‘more relaxed’ with being ‘less rooted’. He merges being more comfortable with ethnic diversity in the abstract into a story being more comfortable generally, of people being ‘more at home in the mass’ and ‘more truly themselves’ (a truly utopian idea). He even suggests this all comes with being ‘less sentimental’, as if his story is not precisely that.

From all this rhetoric, it follows that the more diversity and more immigration Britain has, the more comfortable, relaxed, at home in the mass and ‘more truly themselves’ its people will become - even though the polling tells us that increasing mass immigration has met with increasing dissatisfaction. But Cliffe does not present his vision as just a dream or personal preference. He presents it as a vision of the actual future-of a Britain that is not just increasingly multi-racial and mixed race but also increasingly and inexorably more liberal and cosmopolitan, so therefore coming to align more closely with his own politics. His story is one of national history moving in lockstep with his personal will.[10]

This account has something of the character of prophecy. At Oxford, Cliffe specialised in the Marxist literature of Spain and Germany, and we can see more than a trace of Marxism not just in his account of a cosmopolitan utopia to come but in his adoption of immigrants, non-white and non-British people together as a class that will bring it about, just by being here in ever-greater numbers. In his account the historical process of change is determined or, in religious terms, ‘written’.

Given the title of his most famous book, The Open Society and Its Enemies, you might expect Karl Popper to have had a similar sort of vision to Cliffe’s, of progress towards an ‘open, outward-looking society’. But Popper’s purpose in that book was to attack political theories of historical destiny just like this, including the various forms of Marxism but also the pseudo-scientific theories of racial supremacy that culminated in Nazism.

Popper called these types of theory ‘historicism’. He said, ‘Historicism... can be well illustrated by one of the simplest and oldest of its forms, the doctrine of the chosen people. This doctrine is one of the attempts to make history understandable by a theistic interpretation, i.e. by recognizing God as the author of the play performed on the Historical Stage. The theory of the chosen people, more specifically, assumes that God has chosen one people to function as the selected instrument of His will, and that this people will inherit the earth.’[11]

As Popper put it, a naturalistic kind of historicism might treat historical change as a law of nature while a spiritual historicism would treat it as a law of spiritual development, and an economic historicism like Marxism would see it as a law of economic development. He said: ‘For the chosen people racialism substitutes the chosen race... selected as the instrument of destiny, ultimately to inherit the earth. Marx’s historical philosophy substitutes for it the chosen class, the instrument for the creation of the classless society, and at the same time, the class destined to inherit the earth.’[12]

Cliffe’s chosen people are immigrants and their descendents: especially non-white people and those of non-British ethnicity and mixed race. We might even call it something like an ‘anti-race’, as the negation and disfavouring of a certain ethnicity rather than the favouring of a specific ethnic group. But this theory is not his alone; rather, it is established consensus - one which found a home in power during the Labour governments of 1997 to 2010. Indeed, we can see many of the old New Labour buzzwords in Cliffe’s paper: ‘modern’, ‘forward-looking’, ‘young’, ‘urban’, ‘technological’, ‘open’ and ‘aspirational’. For a standfirst he quotes Tony Blair approvingly, urging everyone to get into line to fit ‘the way the world is changing’.[13] His prescriptions for policy-makers are straightforward New Labour: more ‘modernisation’ (for all parties), more ‘openness’ to the world, more rapid social and demographic change.

New Labour and beyond: Immigration as modernisation

In September 2000, the New Labour immigration minister Barbara Roche gave a landmark speech calling for a further loosening of immigration controls, largely inspired by a report from the Cabinet Office’s Performance and Innovation Unit (PIU) that lauded how Britain’s foreign-born population apparently contributed 10 per cent more to government coffers than it received. In her speech, Roche focused on this labour market case, referring to ‘modern needs’, ‘the needs of business’ and the ‘emerging needs’ of the global economy to justify further liberalising migration rules.[14]

This embrace of modernity as necessity is a hallmark of New Labour and has remained an article of faith for its original proponents like Tony Blair, followers like Jeremy Cliffe and imitators including David Cameron and George Osborne. In her speech Roche stuck very much to this modernising free market model, saying, ‘Whatever we do, it is important that we preserve and enhance the flexible and market-driven aspects of the current work permit system.’[15] But for Roche and others these free market economistic arguments played into another purpose of theirs. As Stephen Boys-Smith, head of the immigration directorate at the time, recalls, ‘It was clear Roche wanted more immigrants to come to Britain... She didn’t see her job as controlling entry, but by looking at the wider picture “in a holistic way” she wanted us to see the benefit of a multicultural society.’[16]

During the 2000s Roche was an enthusiastic proponent of American-style ‘nation of immigrants’ rhetoric which, while maybe appropriate to the United States (with a respectful nod to those who were there before the colonisers arrived), is rather more dubious when applied to Britain. Andrew Neather, a New Labour speechwriter who worked for Roche on her speech, has related how, ‘Despite Roche’s keenness to make her big speech and to be upfront, there was reluctance elsewhere in government to discuss what increased immigration would mean, above all for Labour’s core white working-class vote.’[17] This fed into the way the inner circle around Tony Blair dealt with it.

Blair’s own views on immigration in office veered from serious enthusiasm to serious concern, telling his Home Secretary Jack Straw once that ‘Immigration is good for Britain’ and ‘won’t be an issue’, while at other times fretting that it was the only thing that could lose him elections.[18] David Blunkett, Home Secretary from 2001 to 2004, has said, ‘It changed almost monthly, so there would be, “Yes, we’re a global player, we believe in a labour market - if there’s going to be free movement, well, we might as well have the right to work rather than the right to be here.” Then the next minute, “What does this mean? Have we got worries about the BNP?” - bearing in mind that from 2000 onwards rightwing parties across Europe were actually becoming quite predominant.’[19]

But the pressure from other sources, including increasing ease of travel and demand for migration, overwhelmed any desire not to get on the wrong side of the public. Blair’s pollster Philip Gould thought Labour could contain the issue, while there was genuine enthusiasm from the Treasury and other economistic sources.[20] The British-American economist Jonathan Portes in particular was a staunch advocate, having authored the Cabinet Office report on which Roche based her ‘landmark’ speech.

Moreover, after eighteen years of Conservative government, immigration appeared as a convenient way for Labour to achieve the sort of social changes its big transforming rhetoric had promised, not least in correcting the perceived racism of previous years. The journalist John Harris highlights a remarkable passage from one of Blair’s former advisers, the ex-Independent assistant editor Charles Leadbeater, in which he said, ‘Strong communities can be pockets of intolerance and prejudice. Settled, stable communities are the enemies of innovation, talent, creativity, diversity and experimentation. They are often hostile to outsiders, dissenters, young upstarts and immigrants. Community can too quickly become a rallying cry for nostalgia; that kind of community is the enemy of knowledge creation, which is the wellspring of economic growth.’[21]

Labour started work on relaxing controls as soon as it came to office. David Goodhart points to four decisions in the period 1997–2003 that proved especially important. First was the abolition of the primary purpose rule in 1997 which resulted in a big increase in the inflow of foreign spouses - ‘a payback to Labour’s loyal South Asian voters’, Goodhart says. Second was the introduction of the Human Rights Act and a more active judiciary which made it harder to clamp down on the increasing waves of asylum seekers and deport those who were not genuine refugees, ‘which in most years was the majority’, he remarks.[22] Third was a liberalisation of student visas and work permits, both of which more than doubled after 1997 and which the government used to reduce its asylum problem. Tom Bower writes of this: ‘The only immigration issue that ever truly concerned Blair was the increasing flow of bogus asylum seekers, which after 1999 became an election issue. That problem was partially solved by sleight of hand. With his full connivance, more than 350,000 asylum-seekers were rapidly converted into economic migrants - complete with work permits and rights to benefits.’[23] Finally there was the decision in 2003 to open the British labour market to new Eastern European EU states before any other big country did so.

The loosening of controls had an immediate and also lasting effect. According to official estimates, two million migrants arrived from EU countries alone in the ten years after accession, including 853,000 Poles.[24] Net annual reported migration to Britain (estimated immigrants minus emigrants) quadrupled during the Labour government years according to official figures. Total net migration of foreign citizens (so, excluding net migration of British citizens) during the period 1997–2010 is estimated at 3.6 million - an average of 280,000 per year. This sort of rate has continued since. The impact has been startling, especially in Britain’s cities and towns, in many of which white Britons have rapidly become a minority. The 2011 census figures showed that this had already happened in London, much earlier than experts had predicted.

In his now-notorious article in the London Evening Standard in 2009, Neather said of this, ‘It didn’t just happen. The deliberate policy of ministers from late 2000 until at least February last year [2008], when the government introduced a points-based system, was to open up the UK to mass migration.’ Neather described discussions on policy which revealed ‘a driving political purpose: that mass immigration was the way that the government was going to make the UK truly multicultural’. In an especially controversial passage he said, ‘I remember coming away from some discussions with the clear sense that the policy was intended - even if this wasn’t its main purpose - to rub the Right’s nose in diversity and render their arguments out of date.’[25]

The aim of making Britain truly multicultural would seem to have been achieved already, but advocates remain as committed as ever to pressing ahead for more and more of this repopulation. The rhetoric of modernisation has become ubiquitous in the process. In demanding a looser visa regime, for example, Confederation of British Industry (CBI) director-general Carolyn Fairbairn has said this would facilitate a ‘modern’ immigration system, aligning the business interests she represents with modernity as a story of continuing mass immigration driving ever-increasing economic activity.[26] Immigration appears like this as a project, calculated and orchestrated to deliver a form of technical improvement which is definably modern, taking hold of and maximising existing trends - something which makes the project ‘conservative’ in a sense as well as ‘progressive’ by aligning itself with the dominant social powers of our time. This draws out other aspects of the progressive story, of its attachment to rationality and even morality. A Financial Times leader article against the ‘anti-immigrant tide’ in December 2015 said, ‘The issues of mass migration, the surge of refugees from war zones and the threat from Islamist terrorism have for some time assumed outsize importance in the domestic politics of Europe and the US. This year, the three issues became ever more intertwined, to the detriment of common sense, reason and human decency.’ As well as claiming these three mantles of common sense, reason and decency, the FT said that politicians were ‘suffering the effects of years of pandering to anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiment’, so making sort of false consciousness argument we might normally associate with the left and orthodox Marxism.[27]

Meanwhile, back in the Labour Party, little has changed in the way it deals with immigration as an issue and as policy since Blair came to power in 1997. As policy, mass immigration was not mentioned in any of New Labour’s election manifestoes, yet, as Goodhart has pointed out, ‘In thirty years’ time New Labour’s immigration policy will almost certainly be seen as its primary legacy.’[28] In the 2015 General Election campaign, Labour candidates were told to not speak about it, despite the vague promise of ‘controls’ on migration being one of the party’s pledges. ‘We don’t speak on immigration because we’re afraid of upsetting certain sections of the London Labour party’, the blunt-speaking (and now disgraced) Rochdale Labour MP Simon Danczuk said of this.[29]

This issue may be variously avoided, played down and covered up in how the Labour Party addresses what were (and in some places still are) its core working class voters. But in London and wider liberal-left circles it is very much a cause to gather around, and moreover one which is promoted vigorously using language that appeals variously to ‘modernisers’, economistic and business sources and the multiculturalist and more revolutionary parts of the left.

The statistical generalisations of economistic immigration advocates about relative economic performance have especially emboldened a wider group of liberals and left-wingers to more or less openly promote the idea that the best thing for the British (and especially white British or English) people is to displace and replace them with people from elsewhere. This is another example of the recurring tendency of social science in history to provide justifications for the promotion and suppression of different types of people on account of their identities, such as their class, race and gender. In this case a statistical conclusion has translated quickly and easily into an assumption that foreign-born people are better than British native-born.

Underlying this approach is a treatment of human beings as objects discoverable by their properties-an approach which is amenable to bureaucratic intervention because it takes as important that which can be found out from a questionnaire and easily accounted for on a spreadsheet. We come to treat people on the same terms that our dominant modes of politics treat other objects: as resources that the planner can evaluate and manipulate to achieve optimum results, without having to come into contact with them in any other way. Through this process, the natural world and people alike come to serve as technology or raw material: as natural resources and human resources which the planner can optimise to achieve whatever he or she is trying to achieve. In this way those taking an economistic perspective can openly deride and marginalise broad swathes of the population seemingly without contradicting their aim to improve the state of the country and, by implication, its people.

This technocratic way of looking at the world has fed straight into the narratives and ideologies of the system of diversity, providing supposedly rational, scientific justification for its racial favouritisms by upholding immigrant populations as better, more valuable specimens of humankind than non-immigrants and therefore deserving of favourable treatment. In this way of looking at it, immigrants as a class appear as a sort of chosen people, as agents of the dominant forces of history: of progress, modernity and globalisation. This survival of the fittest narrative has distinct Social Darwinist echoes and serves as a further justification for favouritism alongside the traditional appeals to racial discrimination and disadvantage. The two justifications may be philosophically opposed, but politically they find themselves allied.

Defining ‘us’ and ‘them’: Inclusion and exclusion

Sadiq Khan’s successful campaign to become London Mayor employed these themes to great effect, relentlessly playing up his immigrant parentage, skin colour and Muslim religion as more representative of London than his opponents. During the Labour candidate selection process Khan’s close ally Tulip Siddiq MP said to party members: ‘As the son of immigrants who grew up on a council estate he embodies our modern, diverse and liberal city. He will connect with Londoners from all backgrounds.’[30] Despite the uniting sentiments of the second sentence here, we can see a clear ‘us’ and ‘them’ contrast in the first sentence, a contrast which aligns Khan as non-white-skinned and of an immigrant background with London, modernity and diversity (and also with being liberal) against people who are not these things - so lumping in white-skinned and non-immigrant identifiers with backwardness, racism and illiberalism. It is a version of London and a form of politics that implicitly excludes most clearly older white people, who are seen to be of the past and therefore out of date and irrelevant in the ‘modern’ city.

Those contrasts recurred again and again in Khan’s campaigns, both for the Labour nomination and in the Mayoral contest itself. In the former contest, Khan said of his main opponent, Tessa Jowell, ‘I don’t think she’s got the answers for the 2020s... we’re a modern city, we’re young, we’re diverse.’[31] Again here, we can see him explicitly attaching goodness in politics to modernity, youth and diversity as things that he represents and that Jowell (in this case) does not. In Khan’s explanation, Jowell should not be London Mayor partly because she is not diverse, contrasting her as an older white woman to a ‘we’ of London which is that, as well as being modern, young and of the future. The ‘we’ of London is specifically one that is not attached to those who do not count as diverse. The racial politics is more implied than explicit, but clearly there.

The commentator Yasmin Alibhai-Brown came out with a similar message. ‘I am uneasy about Tessa Jowell getting selected’, she said. ‘She is a woman, talented and persuasive. Yet she is an establishment figure while her rivals - Sadiq Khan, David Lammy and Diane Abbott - are not so grand. They are the children of migrants and so better reflect London, the world’s most diverse city, made by incomers.’[32]

Here we can see once again the dominance of an identity politics in which non-white and immigrant identifiers come up against a female identifier among other things and trump them. But there is also a sense of right attached to this preferentiality: that those of migrant backgrounds should now own and run London because of its diversity - and also because they apparently built it. Khan made a similar point during the EU referendum campaign. ‘It is our open attitude that helped to build our country’, he said, adding that, ‘It’s why London became the great city it is today. It’s why we attract the best and the brightest from around the world to make their home here.’[33]

By talking about ‘our country’ and ‘our attitude’, Khan is talking about a form of ownership not just over London but the country that he explicitly attaches to his attitude and his brand of politics. The ‘us’ here is the liberal-left, which through its goodness (instantiated in its ‘open attitude’) attracts the best people in the world to come and live under its umbrella. This is Jeremy Cliffe’s utopian story of past, present and future gathering around an ‘us’ defined by this open attitude, one which in turn defines immigrants to London as the best and brightest. Always, there is an implicit contrast with those who are not so open in attitude and who are not immigrants so do not qualify for inclusion or praise. These people are not part of this story, of the ‘us’, of ‘our attitude’ and ‘our country’. According to the story, they have no part to play in the future, and have done nothing to build the present. It is a tacit inversion of the old white racism which maintained that Britain and London were white places, owned by whites and places where non-whites did not belong.

This story fits in to an existing liberal-left framework and narrative of favouritism which excludes implicitly but rarely makes this explicit. But here we are not just talking about non-white politicians and writers practising identity politics among themselves and for themselves. Rather, they are preaching to the wider Labour and liberal-left tribe, and also to Londoners in general as their in-group. It is important to recognise that this agenda of racialisation and preferentiality is widely accepted and embraced, especially within the Labour Party, whose rules and structures institutionalise it. White-skinned members of the London Labour Establishment routinely use the same sort of language and in the same way. In backing Khan’s candidacy, the well-respected MP for Barking, Margaret Hodge, said repeatedly that she thought someone of coloured skin should be Mayor in 2016 due to London’s diversity. Jowell herself boasted after the 2014 European and local elections that ‘These results [in London] show London to be an open, tolerant and diverse city’ - thereby drawing a clear and approving contrast from London to the rest of the country, in which UKIP topped the poll.[34]

This attitude perhaps reached a peak in a nascent London independence movement which flared up following the EU referendum result in June 2016. James O’Malley, who set up a petition which attracted 175,000 signatures within a few days, said that, ‘given Britain had just rejected a cosmopolitan, outward facing world, London should reject Britain: We should demand independence - or Londependence - for our city. We should join the rest of the world, even if the rest of the UK doesn’t want to.’[35]

The London city state idea had actually been drifting around liberal elite circles for a few years before the referendum. Its sudden popularity revealed an existential estrangement from the rest of the country among London’s liberal-left elites, and a certain degree of contempt that goes with it. But it also demonstrated a remarkable confidence in their own social and political power, that effectively annexing their country’s capital city on behalf of their politics and value system is genuinely feasible and desirable.[36] As a value system, this one equates the good with and thereby gathers around,

The implicit other side to this coin is that areas outside London which are not so diverse and not changing so fast are bad and need to be changed, a view expressed brutally by the Blairite spin doctor turned columnist John McTernan when he wrote, for the Policy Network think tank, ‘There is nothing wrong with UKIP voting parts of England that a solid dose of migration wouldn’t fix. Nothing.’[37] This desire to repopulate the country in order to displace undesirable people and replace them with desirable others is often implicit in liberal-left discourse, but sometimes we see the desire to discipline and punish coming out into the open, as here.

This sort of politics is widely promoted as a ‘liberal’ agenda, but we might see that it is rigidly selective in its liberalism: offering space to some but seeking to corral others; offering tolerance to some but clamping down on others; approving some as diverse but not others. As Chantal Mouffe has said, ‘Every order is political and based on some form of exclusion.’ The politics of diversity is no exception.[38]

Jeremy Cliffe’s paper outlining his prophecy of Britain’s cosmopolitan future feeds into this story, equating liberalism with immigration and immigrants - and especially non-white immigrants. Explaining the rapid growth in the non-white share of population in some marginal constituencies, Cliffe says, ‘The cosmopolitan tide is advancing on middle England.’ Talking about the increasing ‘Londonisation’ of Britain, he says: ‘Stick a pin in a map of the country and it is ever-more likely that you will hit somewhere that could be described as urban, even metropolitan, where non-white faces are common, where same-sex couples can walk down the street hand-in-hand without raising eyebrows, where many residents have been to university and are internationally minded - in short, places with at least a dash of London about them.’[39]

In that latter passage, we find the equation of ‘non-white faces’ with gay couples walking happily hand-in-hand down the street as if the latter naturally follows from the former - something that will be news to people in certain areas. Actually, polling conducted by YouGov for the gay website PinkNews suggested that Londoners were more than five times more likely to reject support for a gay child than the national average - with 13 per cent of Londoners indicating they would not support a gay child, and 20 per cent indicating they would not support a child who wanted to change their sex.[40] This may seem perplexing to middle-class progressives who flock to London from all over the world to share a space with others of their kind, but it might make more sense in thinking about London as a divided and increasingly segregated place, something that is probably inevitable given the need for people to be around those who share a similar culture.