3. The Favoured Groups

I speak on behalf of my community because they have no voice. Because I speak on behalf of them.[1]

-The King of Dawah (@MoDawah)

Just two months after jihadi terrorists had murdered twelve of its staff in Paris, the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo was given an ‘Islamophobe of the Year’ award at a bash in London. Explaining this and its other ‘Islamophobia Awards’, a spokesman for the awarding organization, the Islamic Human Rights Commission (IHRC), said they have ‘come to be known as a tongue in cheek swipe at those in public life who have perpetrated or perpetuate acts of hatred against Muslims and their faith.’[2]

You may think this is just a bunch of idiots of no consequence who should be ignored. In this you would be broadly correct. However, many major figures in our public life have not taken that course. Jeremy Corbyn for example has said, ‘I like the concept that Islamic Human Rights Commission represents all that’s best in Islam’, and has attended IHRC events since becoming leader.[3] The organisation and its awards have also received messages of support from Dr Rowan Williams as Archbishop of Canterbury, the prominent Liberal Democrat Sarah Teather, Labour MP Yasmin Qureshi and various members of the House of Lords, while it has received funding from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, which funds a range of left-wing and identity-based causes.

This support is not overwhelming, but it demonstrates how the administration of diversity relates to favoured identity groups, by giving favour (and therefore outsourcing power) to certain representatives even if those representatives engage in some distinctly dubious practices. Corbyn saying that this unpleasant organisation represents ‘all that’s best in Islam’ is poor judgement. But his and other examples of support serve to bolster and give credence to the IHRC, making it appear to represent the group which it claims to represent and showing group members it has influential friends.

In this way the likes of Corbyn and Dr Williams are interacting not just with the organisation itself, but with the people it claims to represent - creating a system of representation on three broad levels:

- Those people and institutions which administrate diversity by outsourcing authority to favoured group representatives;

- The representatives of the favoured groups, including their institutions; and

- Favoured identity groups members, who are represented by the people and institutions the administration of diversity outsources authority to.

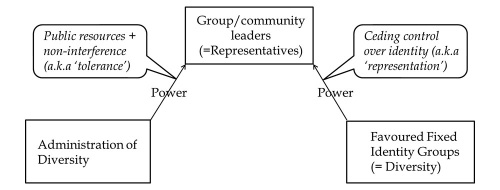

As we can see from the diagram below, the system of diversity works to concentrate power with the group and community leaders or representatives. In order to gain access to the power, resources and favour that flow down through the system, favoured group members must align in some way with these representatives. Likewise, members of the liberal-left must outsource authority to these leaders in order to fulfil their role.

The concentration of power with identity group representatives

So the outsourcing of power to group and community leaders is primarily a top-down process, led by the leaders themselves with the support of the liberal-left administration of diversity which gives way to them. It therefore leaps in on behalf of favoured group members, strapping them into a specific form of representation - binding them not just to those representatives who have been approved for them, but to the very idea of being bound to this sort of representation.

As we have seen, this concentration of social and political power can have some negative consequences. It offers a sort of generalised preferment and protection to favoured group members. But, when institutionalised, it also gives representatives the power to direct favour to whoever they wish - so to people that align with their politics. This discretion and the powers of patronage that come with representative status is a large part of identity group representatives’ power. It bolsters their ability to administer versions of identity which exalt their own status and their own interests above those of their groups.

There is also a clear incentive here for representatives to cordon their groups off existentially (and indeed physically) in order to maintain the integrity of these relationships, distancing them from other forms of political association and emphasising their differences from other groups. The groups represented need to appear as distinctively separate; otherwise the call for separate representation would not make much sense. This is much easier for ethnic-religious leaders to do than it is for feminists for example, since pre-existing differences in language, culture and religion make separate activity necessary for other reasons. It is a lot more difficult to separate women from men than it is to keep one cultural group apart from another.

Furthermore, these relationships between the administration of diversity, the favoured group representatives and those they represent depend on the existence of victimhood and oppression - otherwise the administration of diversity would have no reason to maintain them. This means there is an alignment between the interests of the group or community leaders and the existence of oppression suffered by their group members. Indeed, this whole system of representation, which supposedly exists to fight oppression and victimhood, is tied to the existence of that oppression and victimhood. In circumstances where there is an absence of it, these power relationships create an incentive to generate some - otherwise the justification for the group representatives’ power would slip away. In order to keep all of its relationships of power in place and the resources flowing, the system of diversity must constantly bring to light instances of victimhood suffered by favoured groups, while suppressing instances where this victimhood is lacking.[4]

The very need for suffering and victimhood puts these relationships under constant strain, and this is where the weaknesses of the system of diversity lie. They are the same weaknesses left-wing parties have had in their claims to represent working class people - that working class people do not always want to play the role of passive victims, and others may not always think they deserve that role. As Karl Popper said of communist parties back in 1945, ‘their tacitly implied principle: “The worse things are, the better they are, since misery must precipitate revolution”, makes the workers suspicious...’[5]

From identity representation to administration

The natural authoritarianism of the politics of identity is perhaps most obvious in this group representative role. For the idea that my group must have power easily morphs into the idea my group’s representatives must have power and this in turn easily becomes the necessity that I, as a representative of an oppressed group, must have power - and that all sources of competing power must be eliminated. The politics of identity is a politics of authority above all. In history it has often degenerated into more or less pure power politics through characters such as Stalin, Mao and Pol Pot. But this authority always has an apparent foundation in knowledge, especially of group victimhood.

In drawing others to give way to this authority, the passive voice can be a useful tool, for it frees us to talk about things happening - or being done-without the need to deal with any particulars about who or what is doing it, or who or what is on the receiving end. For example, when the feminist campaigner Caroline Criado-Perez says ‘All women are oppressed purely on the basis that they are women. ALL women’, she is talking about cause and effect; but she is not talking about any actual instances of either.[6] A statement like this cannot possibly be falsified because it does not refer to anything specific. It is insulated from even the possibility of being proved wrong. The passive voice draws us off into a world of broad generalities. The same goes for Islamist talk about ‘the victimisation of two billion Muslims around the world’ and other such things. It is such a big claim that we cannot get to grips with it. Both claims address oppression as something universal while covering up the messy details of how victimhood and oppression work in reality.

In insulating their big claims from even the possibility of falsification, group representatives mine a rich vein of political power which helps them to establish and maintain their relationships of representation. By claiming to understand the experience of all group members fundamentally - as victimhood - the representative claims a form of authority over them - one of knowledge, like that of a religious leader who knows the ultimate truth and guides the chosen people to a Promised Land. It is a political relationship, in that the knower claims authority not just over what is going on but over what should be done about it.

A large part of the system comes under the rubric of multiculturalism, which Trevor Phillips effectively presided over from 2003 to 2012 as chair of the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) and its successor organisation the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC). He has said:

After 12 months at the CRE I had come to the conclusion that, while beautiful in theory, in practice multiculturalism had become a racket, in which self-styled community leaders bargained for control over local authority funds that would prop up their own status and authority. Far from encouraging integration, it had become in their interest to preserve the isolation of their ethnic groups.

In some, practices such as female genital mutilation - a topic I’d made films about as a TV journalist - were regarded as the private domain of the community. In others, local politicians and community bosses had clearly struck a Faustian bargain: grants for votes. And I saw a looming danger that these communities were steadily shrinking in on themselves, trapping young people behind walls of tradition and deference to elders.

Of course none of this was secret.

But anyone who pointed the finger could expect to be denounced for not respecting diversity.[7]

As Phillips points out, the interests of those claiming to represent the various groups are tied to their separation and isolation from wider society. The separate streams of public money and power available to favoured groups incentivises representatives to separate their groups off as much as possible, to emphasise their victimhood and their need for special, favourable treatment as separate groups. By maintaining group integrity they maintain their legitimacy with administrators of diversity. Also, demonstrating the goods they have secured from the authorities helps keep fellow travellers and identity group members on side. This is how the system works: liberal-left administrators outsource power and resources in order to deal with structural victimhood, thereby creating an actual structure overlaying the theoretical, ideological one.

Islamist representation

Muslim victimhood is an essential and recurring theme in how Muslim representative organisations present themselves to the world. It also serves as a tool with which to respond to radicalisation in their communities, by reframing the issue as one in which the state and society are the real perpetrators and Muslims are the victims; so it appears as knowledge - that Muslim victimhood causes radicalisation. We can see this stance expressed particularly strongly in relation to the anti-extremism ‘Prevent’ programme, which the Conservative-Liberal Democrat government changed in 2011 out of concern that it was working with and directing funds towards organisations that promoted extremism and that resisted ‘our values of universal human rights, equality before the law, democracy and full participation in our society’.

When the Counter-Terrorism and Security Bill of 2015 put Prevent on a statutory footing, the leading Muslim representative body, the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB), protested vociferously. In a statement, Dr Shuja Shafi, Secretary General of the MCB, said: ‘Whether it is in mosques, education or charities, the perception is that all aspects of Muslim life must undergo a “Prevent compliance” test to prove our loyalty to this country. The proposed Bill will add to this climate of fear and victimisation within the Muslim community, further weakening trust with public authorities.’[8]

In responses like this we can see a focus on the reaction within Muslim communities rather than the Prevent legislation and actions being taken under it which are apparently causing the reaction. The wording here is of ‘perception’, ‘fear’ and ‘victimisation’, a focusing on something that had already occurred in Muslim communities, with the MCB representing that response as if it is just passing something on. Prevent provides a focus for the idea that any bad happenings are the result of actions from outside the Muslim community which are ‘further weakening trust with public authorities’, therefore leaving open blame for any future events to be attached to those authorities.

But while repeatedly attacking the government using sometimes quite strong language like this, the MCB is also constantly pleading for government money; indeed these seem to be two sides of the same coin. In another statement in which he criticised the ‘McCarthyist undertones’ of government policy, Dr Shafi focused much of his attention on the distribution of public funds, saying, ‘Past mistakes should be avoided where monies were and continue to be doled out to organisations or individuals whose main or primary qualification is to serve as echo-chambers for what Government wishes to hear.’[9] He advocates ‘long-term capacity building and empowerment of Muslim civil society organisations and addressing structural socio-economic imbalances’, so again refocusing attention on Muslim victimhood and the need to address it by directing public funds towards organisations like his own and away from others.

The constant interlocking themes of the MCB’s communications with the outside world are of victimhood but also of its authority as representative of Muslims. These messages have been falling on deaf ears in central government during recent Conservative-led governments, but Labour Party spokespeople in opposition have been echoing these sorts of messages almost to the word.

Richard Burgon MP, as Shadow Justice Secretary to Jeremy Corbyn, has said for example, ‘There is overwhelming evidence that “Prevent” is scapegoating the Muslim community and is operating in an Islamophobic manner.’[10] The Bethnal Green and Bow MP Rushanara Ali responded to the death of a girl with ISIS in Syria by recasting the issue into one of Muslim victimhood related to Prevent, referring to ‘concerns about young Muslims being stigmatised’ and emphasising that the government must ‘listen to the Muslim community and the dangers the Muslim community face’.[11]

Each of these - the MCB, Burgon and Ali - all pick up on radicalisation as a problem caused by the government policy that is trying to prevent it. The effect is to shift responsibility away from members of the favoured group and on to those who are not favouring it, who are not administrating diversity to them. The actual Prevent guidance for identifying and referring individuals vulnerable to radicalisation states that, ‘There is no single route to terrorism nor is there a simple profile of those who become involved... Outward expression of faith, in the absence of any other indicator of vulnerability, is not a reason to make a referral to Channel.’[12] Yet from major Labour and other liberal-left politicians we consistently hear sweeping accusations based not on the content of Prevent but on the interpretation of organisations like the MCB, repackaged and framed as ‘evidence’: so taking their partial views as trusted and reliable and outsourcing authority to them - a classic instance of the system of diversity in action.

In her review ‘of integration and opportunity in isolated and deprived communities’ in Britain, the Dame Louise Casey noted ‘the increasing prominence of an active lobby opposed to Prevent. In some cases, local leaders have been too ready to complain about Prevent without any real understanding of its work or knowledge of its community-based projects and partnership working with local people on the ground.’ She added, ‘More worrying are some elements of this lobby who appear to have an agenda to turn British Muslims against Britain. These individuals and organisations claim to be advocating on behalf of Muslims and protecting them from discrimination. We repeatedly invited people we met who belonged to these groups, or who held similarly critical views, to suggest alternative approaches. We got nothing in return.’[13]

Of course this sort of politics is by no means exclusive to the system of diversity. It is a natural feature of democratic politics that politicians are drawn in by powerful lobbies. But this is where the system and representatives of favoured groups have arrived at - a position of power.

Feminist representation and positive administration

Looking at women’s representation, we can see a similar process in operation, with liberal-left administration outsourcing power and resources to feminist leaders and organisations on the basis that they represent women. Through the outsourcing of power in this way, a group of mostly confident, highly educated, middle class women have established themselves in structures of preferentiality that are meant to redress structural disadvantages facing women as a group. As the economist Alison Wolf puts it, ‘There is a complete preoccupation in feminism with the economic self-interest of the top people, whether it’s [on company] boards or parliament.’ She adds, ‘There has been an obsession with what is going on at Oxford or Berkeley because it involves “people like us”.’[14]

For feminists, the word ‘representation’ itself plays a crucial role in establishing the role of women in elite positions as being to represent other women. A lack of women in top positions in institutions is grounds to demand more, again for the sake of this representation, conferring on women in positions of authority specifically feminist responsibilities. This constantly works to direct power towards feminists themselves, while making those who do not obviously fulfil this role, like Theresa May and Margaret Thatcher for example, appear like imposters. As the former Labour deputy leader Harriet Harman put it, ‘like Margaret Thatcher before her, Theresa May is no supporter of women... Theresa May is a woman - but she’s no sister.’[15]

Around the Labour Party, the flagship of women’s representation is the All-Women Shortlist for Parliamentary candidate selection, but favouritism in securing positions goes right down to the micro-local level. There has also been a big focus on speaking panels at conferences and political events, to the extent that ‘all-male panels’ at Labour conferences have been banned by the party’s National Executive Committee (NEC) and fringe meetings held up as organisers frantically search around for a woman, any woman, to speak at them. Bex Bailey, as youth rep on the NEC at the time, said of the banning, ‘All-male panels are damaging because they sustain a political environment and culture in which women are excluded. Giving women a platform helps to end this cycle of exclusion, while giving us the experience and exposure to start breaking down the barriers to further progression. It also has a wider impact on women’s representation by providing role models for future generations.’[16]

This is an argument of entitlement, that it is specifically ‘us’ that need to be promoted in order to overcome exclusion suffered by women. We might think of it as another version of ‘trickle-down’ theory, in which the promotion of these particular women trickles down to benefit all women, not least by them using positions of power to promote more of the same preferentiality and favouritism - so promoting more of ‘us’ who will then provide more representation, and so on. While the activists say they represent those not so fortunate, in practice the system of diversity quite clearly acts to benefit them while the less fortunate seem to stay less fortunate for the most part, continuing to serve as statistical fodder to demonstrate group victimhood and the need to promote more of ‘us’ in order to correct it.

In promoting representation like this, feminists make a jump which is barely discernible but important, from claiming and asserting their representative authority to upholding group representation - of certain groups - as a good in itself. In doing this, they jump from promoting the victimhood of their group to a positive form of politics, which advocates more representation for all the system of diversity’s favoured groups. As a form of positive identity administration, it goes beyond the stories of victimhood and oppression. After all, these stories may provide a bedrock of solidarity but fail to provide any sense of possibility, purpose and the prospect of an attractive future. In order to bind people in, identity administration needs a bit of this: offering a purpose in life and to life, something to aim for and something worth aiming for. For feminists this positive identity is provided largely by this idea of representation, which feeds back into promoting feminists themselves but also leads into promoting identity representation for other victimised groups.

By focusing on identity-based representation as a general good like this, feminists align themselves with the liberal-left administration of diversity and liberal-left positive identity. They make an issue of fixed identity and the need to provide certain identity groups with dedicated representation and favour. In this way mainstream feminism stands to represent women as an identity group while offering a positive identity (prescribing what should be done, how, and by whom) that places feminists firmly within the wider liberal-left tribe, which outsources authority to them. It is concerned much more with what feminists should do and what liberal-left institutions like the Labour Party and The Guardian should do than what women should do, except that they should consider feminists as representatives of women - so again feeding back into feminist power.

Islamist positive administration

There is quite a contrast here with the positive identity administration of some other fixed identity group representatives, notably Islamists. While feminists (and also LGBT+ groups) have largely merged their positive identity into that of the liberal-left tribe, Islamists fit more rigidly into the demarcations of the system. Like feminists, they relentlessly play up group victimhood in order to secure their representative status from the administration of diversity, but the positive identity they administrate is for the fixed identity group they represent - Muslims. Mainstream feminists like to tell other feminists and administrators of diversity how to behave but they tend to avoid dictating individual behaviour to women. Islamists are constantly instructing Muslims on how to act, what it means to be a good or ‘true’ Muslim, who does not meet these criteria and who the enemies of Muslims are.

Comparing Islamists and feminists in the system of diversity

David Goodhart has pointed to a study by the Danish academic Jytte Klausen which found that around 70 per cent of the British Muslim elite (MPs, councillors, community activists) were ‘neo-orthodox’ in leaning - a far higher number than in other countries - ‘meaning that they regard liberalism as anti-Islamic and think it is possible “for Muslims to live separately but as loyal citizens in the West”.’[17] You do not have to look far to find examples of this sort of tendency from representatives of Muslim communities in Britain. From Muslim organisations and representatives we can see a consistent spreading of a positive Muslim identity which emphasises maintaining separation from and hostility to non-Muslim Britain, promoting conservative Islamic ways while attacking more liberal practices both internally and externally.

In Dewsbury in Yorkshire we find Islamic Tarbiyah Academy, a private Muslim school, distributing leaflets from its founder and head Mufti Zubair Dudha claiming that colourful pictures, films, magazines and sporting celebrities are part of a conspiracy to ‘poison the thinking and minds’ of young Muslims, while quoting The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the early 20th-century anti-Semitic forgery which claims to prove a global Jewish conspiracy. In a section on jihad, Dudha, a respected cleric from the Deobandi sect which controls around half of the mosques in Britain, tells Muslims they should be prepared to ‘expend... even life’ to create a world organised ‘according to Allah’s just order’. Sky News reported other literature at the school warning Muslims not to adopt British customs, banning television, saying that all mixed-sex institutions are evil and telling women not to go out to work and to be fully covered before leaving the house.

At a mosque affiliated to the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB) in South London, the imam tells his flock how, ‘Adopting the lifestyle of the non-Muslims is in itself association with them and therefore sinful. To wish non-Muslims during their festivals is also unlawful. The non-Muslims display acts of disbelief during their festivals. To wish them in their festivals is a sign of gratification to disbelief.’ He also quotes Allah’s words from the Qur’an, ‘And do not incline towards the wrongdoers; lest the Fire should catch you, and you have no supporters other than Allah, then you should not be helped.’[18]

The positive administration of Islam is often carried out by way of sharp contrast, distinguishing Muslims as a group from non-Muslims, maintaining a strict ‘us’ and ‘them’ divide contrasting what good Muslims should do with pejorative descriptions of how non-Muslims and those who are not ‘true’ Muslims act. This distinction is one between good and bad, righteous and non-righteous, lawful and unlawful (in terms of the higher law of Islam).

Shazia Awan, a Muslim businesswoman, reports walking out of an event about tackling Islamophobia championed by the Muslim Council of Wales (MCW), an affiliate of the MCB. She says: ‘The speaker who made me walk out was Salafi preacher Abu Eesa Niamatullah whose 45-minute speech I listened to and who, in my view, should never have been given a public platform. (Salafi doctrine can be summed up as a fundamentalist and ultra conservative approach to Islam.)’ ‘This cleric has said many things I disagree with, including his idea of combating Islamophobia by being more orthodox.’ She quotes him making an address to Muslims via the Prophetic Guidance website, saying, ‘Women should not be in the workplace whatsoever. Full stop. I simply can’t imagine how we will safeguard our Islamic identity in the future and build strong Muslim communities in the West with women wanting to go out and becoming employed in the hell that it is out there... I am an absolute extremist in this issue in that I don’t have any time for the opposing arguments.’[19]

The elision between ‘building strong Muslim communities’ and not integrating into wider British society could not be clearer. There is a serious political element to this which we could use to define Islamism as a movement that seeks to maximise the social and political power of Islam as currently constituted and practised, as rigidly separate from what Niamatullah calls ‘the hell that is out there’. Being an Islamist is not the same as being a Muslim extremist or terrorist, but does include them just as the term ‘Irish republican’ includes peaceful nationalists and those who use violence to achieve their political ends. They have broadly the same political objectives in terms of the promotion and expansion (even domination) of a conservative, separatist form of Islam in the public sphere, not just in the private sphere.

Awan says of Niamatullah’s views, ‘I for one will not accept or tolerate such misogynistic and orthodox views in my hometown.’ A minister from the Labour-run Welsh Government administration was not so concerned though, sharing a stage with this man at the invite of the MCW.

The MCB has been active in spreading its ethos through both private Islamic and state schools. In the Trojan Horse ‘plot’, an organisation linked to the MCB called the Park View Brotherhood worked to take over the governance of 16 state schools in Birmingham and introduce what former head of counter-terrorism Peter Clarke called ‘an intolerant and aggressive Islamic ethos’ into them. In separate reports written for the Secretary of State for Education and Birmingham City Council respectively, Clarke and the former head teacher Ian Kershaw recorded a range of offensive behaviours practised by governors, teachers and outsiders invited in to speak to pupils, especially in the three schools run by the Park View Educational Trust directly controlled by the Brotherhood. In these schools they found evidence of sexism, homophobia, racism, bullying and aggression, anti-Western rhetoric, anti-Christian rhetoric and insults to British service personnel, in addition to financial impropriety and nepotism, with positions in school awarded to friends and relatives of governors.

Staff at Nansen Primary School said they were told to teach that homosexuality is a ‘sin’, with the school’s deputy head Razwan Faraz saying of gay people, ‘These animals are going out full force. As teachers we must be aware and counter their satanic ways of influencing young people.’ An undercover reporter recorded the chair of Nansen’s governors Shahid Akmal, a former Revenue and Customs official, saying: ‘Our women are much, much better consciously in the heart than any white women... White women have the least amount of morals.’ Sheikh Shady Al-Suleiman, who was invited to speak at the Park View school, has called on God to ‘destroy the enemies of Islam’ and ‘prepare us for jihad’. Head teachers who would not go along with the Park View ethos were forced out through intimidation and other undermining tactics, receiving little or no support from Birmingham Council or their trades unions.[20]

The Park View Brotherhood was led by the Islamic educational activist and Ofsted inspector Tahir Alam, who wrote a 72-page report for the MCB on the Islamisation of British schools with the MCB secretary-general in 2007. This report recommended how Muslim parents and organisations should press schools to introduce Islamic codes into their activities, including banning dance performances and plays that involved physical contact between boys and girls, or which celebrated other religions.[21]

Characteristically, the MCB’s response to the Trojan Horse affair was to denounce it as a ‘witch-hunt of British Muslims’ which provided ‘sinister caricatures of Muslims that provide fodder for the far-right’. Its statement said that the allegations ‘must be appropriately investigated’ but pre-judged them as ‘far-fetched’ while questioning Clarke’s credibility as an investigator.[22]

Again and again we see the same sort of thing. At the Glasgow Central Mosque, Scotland’s biggest, and affiliated to the MCB, the lead imam Maulana Habib Ur Rehman posted a message on WhatsApp supporting the murderer of the liberal governor of Punjab province Salmaan Taseer, who opposed strict blasphemy laws in Pakistan. Rehman offered Mumtaz Qadri the religious blessing ‘rahmatullahi alai’ and said: ‘I cannot hide my pain today. A true Muslim was punished for doing which [sic] the collective will of the nation failed to carry out.’ The head of religious events at Glasgow Central Mosque has held office in the organisation Sipah-e-Sahaba (SSP), which has committed massacres in Pakistan with the aim of turning the country into a Sunni state under the total control of Sharia law. British government guidance describes another of its objectives as being to ‘participate in the destruction of other religions, notably Judaism, Christianity and Hinduism’.[23]

Representatives of the Glasgow Central Mosque and the Muslim Council of Scotland were invited to attend an inter-faith vigil in honour of the murdered Ahmadi Muslim shopkeeper Asad Khan, but failed to do so, releasing a statement instead complaining about the pressure they were under to describe Ahmadis as Muslim. This echoes the stance taken in 2003 when Ahmadis opened the largest mosque in Europe in South London and the MCB put out a statement telling the BBC and other media not to call it a mosque. This refusal to acknowledge that Ahmadis are Muslims was the motive professed by Tanveer Ahmed, a taxi driver from Bradford, for driving up to Glasgow to kill Khan. Glasgow Central Mosque had previously hosted annual conferences for the Khatme Nubuwwat group which has advocated execution of Ahmadis, with one of the speakers advertised being Maulah Allah Wasaya, who had called for the killing of Salmaan Taseer and has described the Ahmadi as ‘Zindeeq’ - those who claim to be Muslim but hold criminally dissident beliefs.[24]

This strict control over what is acceptable for Islam also bears down on those who appear criticising the mainstream practice of Islam and raising the possibility of doing things differently. Ed Husain and his former activist colleague Maajid Nawaz formed the Quilliam think tank to address extremism and radicalisation within Muslim communities. With his higher public profile Nawaz in particular has faced relentless attacks from Muslim representative organisations and their followers. As Ajmal Masroor, a ‘broadcaster, imam and relationship counsellor’, said during an attack on the Prevent strategy for the left-leaning Huff Post UK website, ‘In the Muslim community [Nawaz’s] name is a swear word to describe charlatans and in the wider community his self-aggrandizement has earned him disrepute.’[25] Nawaz, who advised the David Cameron government on extremism, has experienced death threats as well as the usual litany of abuse - a reality which goes some way to explaining why there are so few alternative and liberal voices contesting the Muslim political scene. This is part of a general pattern of political domination, in which the political space of the identity group and how it communicates with the outside world is tightly controlled, maintaining a strict ‘us’ and ‘them’ demarcation and mounting attacks against critical voices wherever they appear.

In pure political terms, this strict policing and administration of what it means to be a Muslim (or a good Muslim) supports the power of those who police and administrate it. By painting those who are critical about internal Muslim affairs as bad Muslims and whipping up antagonism against them, they protect their own positions. Meanwhile, the ‘good’ or ‘true’ Muslim falls into line, accepting existing representation and authority, and denying internal problems or attributing blame for them to the British government, non-Muslims and the West more generally.

From this situation, we can see some absurd contradictions arising in what representatives say to different audiences - and even the same ones. Shakeel Begg, the lead imam at the MCB-affiliated Lewisham Islamic Centre in South London, took the BBC’s Sunday Politics show to court for libel for referring to his extreme views, only for the judge to confirm he ‘clearly promotes and encourages violence in support of Islam and espouses a series of extremist Islamic positions’. As Mr Justice Haddon-Cave put it, ‘He appears to present one face to the general, local and inter-faith community and another to particular Muslim and other receptive audiences. The former face is benign, tolerant and ecumenical. The latter face is ideologically extreme and intolerant.’[26]

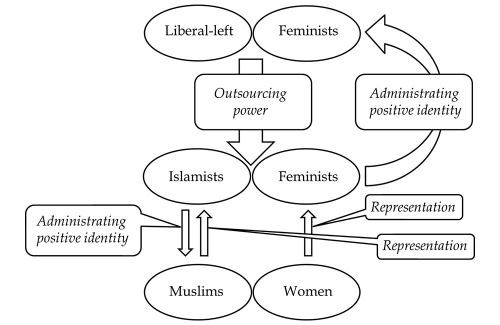

This phenomenon of Islamist institutions and individuals speaking in two different voices, claiming to promote peace and respect for other traditions in one breath, while expressing hostility to those who do not bow to their demands in the next, is not an unusual one. In the system of diversity, identity group representatives are facing in two different directions - up towards the liberal-left administration of diversity (for example, through governmental, political and inter-faith bodies) and down to the group members they represent. For Islamists, these relationships entail the administration of victimhood to gather sympathy from the administration of diversity but also the administration of a positive version of Islam to the identity group of Muslims, with punishments for those who do not conform.

Part of our problem is that this positive version of Islam is often absolutist and accepts no contradiction from within the identity group and sometimes also from outside. A wrongdoer is a wrongdoer, whether Muslim or not. In a book published in 2007, Ed Husain recounted how the president of a leading Islamist organisation in Britain, ‘a man known for his public condemnation of terrorism’, told him over lunch that ‘he considered that he saw nothing wrong with the destruction of the kuffar, or prayers that call for that destruction.’[27] Husain lamented this ‘doublespeak’, asking, ‘For how much longer, I ask, will we tolerate the hypocrisy of such people enjoying British life while calling for its destruction?’[28]

The answer would seem to be: for quite a while yet. Although the Conservative-led government under David Cameron broke off relations with many of the leading Muslim representative organisations including the MCB, Islamist demands continue to draw significant support across mainstream politics and civil society, especially but not exclusively from the Labour Party (in both its far left and more ‘moderate’ incarnations). Cameron said of the government’s decision that, ‘Muslim Brotherhood-associated and influenced groups in the UK have at times had a significant influence on national organisations which have claimed to represent Muslim communities (and on that basis have had a dialogue with Government), charities and some mosques. But they have also sometimes characterised the UK as fundamentally hostile to Muslim faith and identity; and expressed support for terrorist attacks conducted by Hamas.’ The report described the Brotherhood as ‘dedicated... to revolutionising societies and changing existing ways of life’ and said that association with it should be taken as an indication of extremism. It added that ‘for some years the Muslim Brotherhood shaped the new Islamic Society of Britain (ISB), dominated the Muslim Association of Britain (MAB) and played an important role in establishing and then running the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB)’, noting also how the MCB and MAB ‘have consistently opposed programmes by successive Governments to prevent terrorism’.[29] All this is consistent with the Islamist administration we have been looking at.

The existential situation of group representatives

To be effective, identity administration depends on others making way or giving way to it: by allowing, accepting and going along with it; by letting it prevail in the existential space they occupy. Giving way to administration is a form of action through inaction, in ceding authority to others to administrate on one’s behalf.

In the system of diversity, representatives of favoured groups gain power to administrate from two different sources: from members of the group that they represent and from the administration of diversity which directs social and political favour to them. These two different relations feed into and boost each other. The more identity group members align with representatives, the more legitimacy those representatives have in the eyes of the administration of diversity. Likewise, the more favour and resources can be seen coming down to the representatives for their groups from the administration of diversity, the more reason for group members to accept these people as representatives. Forming these relations builds up bonds of mutual dependence and benefit between the different levels of the system, with the group representatives at the centre of it.

For Islamists and feminists, these relations are different in character, as we have seen. There are a number of reasons for this. Competing positive feminist identities for women as women are contentious and often have the effect of irritating non-feminists as well as feminists who hold opposing views. The question of whether female and male are social constructs or are inherently different and distinct appears as a theoretical game with little general appeal or relevance to everyday life. But also, for feminists, dealing with women as a separate identity group is difficult. In practical terms, women cannot be so easily separated off and dealt with in isolation like Muslims and other ethno-religious groups can be by community leaders. Positive feminist identities that oppose men, with whom women share their lives, homes, workplaces and a common culture, may make sense for members of the liberal-left, for whom the negation of one’s unfavoured group identities is a habit, but for those not comfortably integrated into the system of diversity, it can appear as strange and alienating.

Also, a positive group identity needs more than a relentless emphasis on group victimhood and demands for more representation. It needs to offer attractive possibilities as well. These can take the form of positive stories of group identity linked into cultural forms, as with ‘black’ music for example. But for representatives to actually represent in some effective way implies some sort of dependence on them - even if only on the basic level of being part of the group and taking pride in being part of it. If people are dependent on representatives for some of the goods of life, then they have some form of identity relationship in place and are more likely to accept the administration of identity from that source. But, by pushing representation at the elite level, feminist positive identity promises goods that tend to benefit fellow feminists. Most women have no direct, obvious dependence on feminists; the relationships involved are much more flimsy and indirect in nature than those that some Islamist and ethnic-based community leaders maintain.

Nevertheless, feminism has had a great deal of success at this elite level, in capturing political space as the voice of women. This is partly down to steering clear of futile and internecine doctrinal dogfights, not least on the nature of gender, but also those raging between the hard left and centre left. Instead, mainstream feminism has maximised its strengths, perhaps the greatest of which is its integration into the wider liberal-left. Feminists tend to come from the same middle class background as other liberal-left members so the ideology of diversity is familiar and accessible to them. They are part of the same tribe, so naturally find a conducive and appealing environment to advance their interests at this level. Moreover, by playing up their victimhood and demanding extra representation for themselves, they align with liberal-left positive identity which is concerned with outsourcing favour (and representation) to approved victim groups. In this way, they secure representative status from the administration of diversity, even if members of their identity group do not give way to the positive identity they espouse.

By merging into the overseeing caste of the liberal-left, feminists appear to preside over the system of diversity in a way that Islamists and most race- and ethnic-based representatives do not. Islamists do sometimes talk about Muslim representation in wider public life, but to nowhere near the same extent nor with the same merging of identities as between feminists and the liberal-left, who hail largely from the same social and cultural background: liberal, progressive, middle class, prosperous and university educated.

We can hopefully now see how the liberal-left administration of diversity gives way to feminists (and also LGBT+ representatives) partly as a giving-way to itself, as an overseeing caste whose purpose is to offer favour and representation for favoured groups (but not unfavoured ones). By contrast, to Islamists and other group representatives, the liberal-left gives way to something other: to something separate, whose politics are different in character and to whom authority is properly transferred. In both cases, this giving way entails accepting the authority and the positive identity administration of those it has accepted as representative, giving a part of one’s own power to them and thereby establishing a political alignment.

In institutional life, assigning representative status to leaders also entails the allocation of control over resources. This creates an incentive for members of favoured identity groups to accept that representative authority in order to benefit from the flow of resources. These powers of patronage help group representatives to spread their own standards of conformity by placing conditions on the favours they hand out. This might include accepting their administration of group victimhood, but also other things like adhering to a strict version of Islam for Islamists or sharing the broader liberal-left outlook on the world for feminists and LGBT+ representatives.

However there is an implicit choice that representatives must make in order to attain their positions in the system of diversity. As a representative, you must fit yourself into two sets of relationships, one looking upwards to the administration of diversity and the other looking downwards, presiding over your own identity group. These relationships must remain consistent in order for your role to endure. As a representative you depend on both the administration of diversity and the situation of your identity group remaining essentially the same. To avoid disturbing the former, other favoured groups must not be disturbed, which is why we rarely see Islamists and feminists directly challenging each other in public. For the latter, it means that group identities must be kept fixed, with their situation of victimhood maintained. In such a diverse and market-based society as Britain is today, keeping everything in line demands constant vigilance, and your fellow administrators have their eye on you. Displaying correct knowledge of group identity and intervening against deviation meets with approval and acceptance; failure to do so draws disapproval and even denunciation. As an identity administrator, you must pass over your agency to the group and its norms. These maintain group integrity, which in turn helps to keep the whole system intact.

Seen this way, group or community leaders emerge as followers as much as leaders. They must watch out for anything from their identity groups which might threaten the integrity of the system. But they must also keep watch over themselves and be aware that they are being watched by others. They must conform and be wary of stepping out of line for fear of denunciation, loss of representative status and exclusion from the system. Their commitment to the system is always a few wrong words away from being undermined and needs constant renewal to avoid suspicion.[30]

We might see a double aspect here in that, as much as representatives are using the norms they are conforming to in order to achieve their own goals, the norms are also using them as vehicles to maintain and maximise their power. The system is primary and the individual must give way to it in order to feel its benefits.

For someone administrating identity, this is a big constraint, for it requires them to stay within strict bounds and not deviate for fear of the inevitable (indeed systemic) denunciations. Their existential position is fixed just like that of the people they are representing and administrating to. Indeed, due to their greater public profile they are being watched more closely. This is one reason why identity politics never seems to change, except in expanding and becoming more consistent and more effective. Administrators of identity may have control over various types of goods passing up and down through the system, but their freedom to form and shape the terms on which this takes place is strictly limited. They are more like cogs in a wheel or parts of a machine that must remain the same in order for the machine to operate.

There is inevitably a measure of frustration attached to this situation: a feeling of being constricted and held back, of not having the real freedom to actually lead. Group representatives may feel they are always one level down from where ultimate power lies: that their power is contingent on others assenting to it, and that they have to keep fighting to maintain this assent. Feminists, as integrated into the liberal-left, may be closer in and in a more favourable position, but we can still see a great deal of frustration, as with the anger expressed that ‘women’ as a group have been denied the Labour Party leadership on a number of occasions. The temptation to revert back to victimhood is always there, available and convenient. The possibility of going in another direction is fraught with difficulty by comparison.

Stories around victimhood are available and familiar. For an administrator of identity, they are as easy to pick up and use as a knife and fork. The same goes for the representation narrative of feminists, which is ready to hand and ready to use. The same goes for ideas of what a ‘true Muslim’ is for Islamists. They fit into existing life in a convenient way that barely needs any thought and reflection.

Customs and habits like this maintain our identity; in a sense they are what we are, more so because they keep us fixed into a world of relations that would break down without them. By saying and doing the right things, representatives keep themselves in place in relation to others and to other levels of the system. Maintaining their relations with the identity group they represent keeps the group in place in the system, as a victim group, dependent on its representatives. This also keeps them where they are, embedding their power.

These aims are tacit rather than explicit though. Administrators of diversity, identity group representatives and members are not necessarily deciding to maximise the power of the system and the identity group representatives. Rather the system is drawing them in to fit with it, offering possibilities for them to behave in a way that serves to consolidate its power while also providing them with roles and a form of belonging. The system requires that the people involved press into the possibilities offered to them rather than stand back from and question them. To do the latter is after all to stand outside the system, negating it. In being drawn in to the system, we give way to it.

The existential situation of group members

On 17th March 2015, BBC Radio 4 broadcast a programme entitled ‘In Search of Moderate Muslims’ by Sarfraz Manzoor. In it, Manzoor, describing himself as a ‘moderate’ Muslim, said: ‘We are told that they are the silent majority of British Muslims, whose faith has been hijacked by the extremists. But, while they are much talked about, I think they are rarely heard...’[31] What he found was quite startling. As he put it in an article accompanying the programme:

I anticipated disagreement on what defined moderate; what I did not expect was universal hostility to the very phrase and yet everywhere I went the message was the same: don’t call us moderate.

‘I see it as a criticism,’ one woman in Luton told me. ‘You are giving me this label based on how I look and how I dress.’ Her male friend said he found the word ‘offensive’, adding: ‘Are you saying I’m only 50 per cent Muslim? When someone says to me ‘you’re moderate’ it suggests to me they’re saying ‘you’re not fully Muslim’.[32]

There is clearly a lot of sense to these reactions, but the politics of the matter is more complicated. For ‘moderate’ is precisely the term that Western politicians and other public figures (of almost all persuasions) have gathered around to contrast and draw away ‘ordinary’ Muslims from the ‘extremists’. If British Muslims almost universally reject that contrast, it tells us something not just about the failure of our political leaders to reach out effectively, but how the politics of British Muslims today is drawing them to reject this reaching-out, to decline the possibilities that it offers. This aligns with the administration of Islamist leaders in upholding Muslim identity as separate from and hostile to that ‘mainstream, moderate’ and liberal ideal that British and other Western politicians have tried to associate with them. It suggests they have achieved a measure of success in influencing their identity group to think and do what they want them to.

Manzoor’s other findings from his interviews pointed in a similar direction, of young Muslims making ‘them’ and ‘us’ distinctions on the basis that the liberal attitudes associated with ‘moderation’ are against Islam and against themselves as Muslims: a process of aligning to the latter by drawing away from the former. In this account, to be Muslim is to not be aligned with that supposedly moderate, British liberal mainstream, with the adoption of traditional Arab clothing offering a potent symbol of this rejection and acceptance of a specific alternative.

As the Muslim businesswoman Shazia Awan put it, ‘Growing up in Wales I don’t recall seeing women in the full-face veil, now it is a common sight.’[33] Ed Husain and Manzoor point out the same thing in London and other English towns. But examples of separatist attitudes and practices have been appearing from Muslim communities all over. The head teacher at one of the primary schools involved in the Trojan Horse affair told the Sunday Times that some Pakistani heritage children in the playground had been telling their fellows not to play with the few white children who attended her school, while a parent told her that white children should be excluded altogether.[34] Meanwhile in Keighley in Yorkshire we had a situation where the Labour Party councillor Khadim Hussain, who served as the Lord Mayor of Bradford from 2013–14, shared a post on Facebook referring to Hitler’s killing of 6 million ‘Zionists’ while spreading conspiracy theories about ISIS being a tool of Israel. Hussain was suspended from Labour and then resigned from the party for his comments. However, he was promptly re-elected as an independent in the subsequent May 2016 council election, convincingly beating the Labour candidate into second place - showing how a majority Muslim ward (Keighley Central ward was listed as 51 per cent Muslim in the 2011 Census statistics) will happily elect someone who has lost the Labour brand name for making anti-Semitic comments; far from ostracising him, the ‘community’ gathered around and supported him.

We might think a lot of the polling done with British Muslims backs all this up. On anti-Semitism, for example, one poll found 35 per cent of British Muslims saying that Jews have too much power in Britain compared to 9 per cent of non-Muslims.[35] In another poll commissioned by Trevor Phillips for a Channel 4 programme, more than half of the Muslims surveyed thought that homosexuality should be illegal.[36] It is worth bearing in mind the flip-sides, with a clear majority of 65 per cent saying they did not agree on Jews and nearly half not saying that being gay should be outlawed. Nevertheless, the disjuncture between British Muslims and the rest of Britain is clear - and backed up by low levels of intermarriage for Muslim Britons of Pakistani or Bangladeshi heritage compared to other ethnic minorities, with fewer than one in ten being in inter-ethnic relationships.

In his Radio 4 programme, Manzoor spoke about how the BBC in particular had responded to some polling of British Muslims about the Charlie Hebdo attacks. As he put it,

All the BBC headlines were about how many Muslims had allegiance to Britain (and this was borne out in the data, with 95 per cent saying that they felt a loyalty to Britain) - and how the vast majority had no sympathy for the perpetrators of the Paris attacks. It all might make you think that most Muslims are moderate and cosy liberals, except that the polls also revealed that 27 per cent had some sympathy for the motivations behind the Paris attacks and 45 per cent said clerics preaching violence against the West can be justified as being in touch with mainstream Muslim opinion. For me, that’s pretty scary.[37]

Again, we can see a large minority prepared to own up to what we can only describe as extremist views, and an even larger minority agreeing that such views are mainstream among Muslims. Back in 2007, Husain wrote, ‘Long before the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, in Britain’s Muslim communities the ideas of a global jihad, an ummah transcending Britain, and preparation for the all-powerful Islamist state were, and still are, accepted as normal and legitimate... That ideology and its prescriptions are becoming the acceptable norm for expressing political disenchantment against “the West” - a mythical conception just as much as “the ummah”.’[38]

Given the stranglehold that Islamists have on public discourse within and from Muslim communities though, the situation could be a lot worse. A Policy Exchange report co-authored by David Goodhart surveyed more than 3,000 British Muslims and revealed that only 20 per cent of them saw themselves as being represented by organisations that claimed to represent them, with only 2 per cent saying they supported the MCB. It said, ‘Attempts to portray government policies - such as those associated with the Prevent agenda - as anti-Muslim initiatives rejected by the whole community, wildly misrepresent the views of British Muslims.’ In fact, almost half of those questioned agreed Muslims should do more to counter extremism. On the flip-side, though, 26 per cent denied that extremism existed at all, while around 40 per cent believed conspiracy theories circulated about such things as 9/11 had some truth to them. Islamist narratives of victimhood and separatism clearly remain highly influential.[39]

The dangers of non-conformity

This sort of identity formation and maintenance is a process of binding and being bound. In the case of the system of diversity, group and community leaders, with the support of liberal-left administrators of diversity, are doing the binding on behalf of identity group members. They are leaping in to prescribe identity as something unchosen, as fixed identity in the sense that there can be no other way and no question about it. Under the ideologies of identity they propagate, group members are passive receivers of identity. Their fate is determined by the structures and systems of society; it is not theirs to form and shape; choice is an illusion. As a favoured group member, the only people able to mould your fate for the better are the adminstrators of diversity and your group representatives, who have correct knowledge of your situation (as a universal situation) and can intervene against society on your behalf.

However, by taking such things as skin colour, gender and religious grouping as fundamental categories, set in relationships of oppression and privilege (or perpetrator and victim), the range of possibilities that the system of diversity offers end up being remarkably narrow, with little potential to adapt to changing times and blocking off possibilities that might be available to group members from outside the system. Indeed the nature of this sort of politics is to shut down choice and close off alternative possibilities which would weaken its own political power.

In this way of approaching identity as fixed, you cannot turn away and reject identity, because it is who you are. This is a con on one level, because you can turn away from and reject it; but on another level there is more than a little truth to it, for by turning away you forsake the connections that bound you in to be part of something and that made you who you are, as a part of that world. By rejecting that world, you pass from being a somebody to a nobody in relation to it. Without another world or worlds to tie yourself into, you will become an actual nobody, as in being unknown to anybody.

So, from the perspective of the administrators of identity, rejecting the fixed identity they ascribe to you means not just rejecting a set of political beliefs but rejecting yourself. Straying is not just a betrayal of the administrators but of reality itself. It is to deny what is fundamental, which is the underlying reality of your situation in society. If and where that identity is strongly policed, casting it off presents a serious existential challenge, for doing so entails casting off your whole being, the whole basis on which you engage with the world. But there is more at stake here, for social systems like the system of diversity depend on conformity, familiarity and predictability. A challenge to one part of the system potentially poses a threat to all of it. It might encourage others to jump ship and mount challenges. For the system to keep reproducing itself, such challenges must be stamped on and stamped out.

The more tightly bound the group or community is, the greater the challenge will be felt and the greater the likely reaction. Those choosing to give up Islam are not just facing up to a religion but to a whole social system that is embedded in communities and families - and in politics through the system of diversity. Moreover, forsaking Islam makes you an apostate - and the traditional punishment for apostasy is death. One ex-Muslim, Sulaiman Vali, told The Observer newspaper, ‘If someone found out where I lived, they could burn my house down.’ Others confirm threats and potential for violence, although Simon Cottee, author of The Apostates: When Muslims Leave Islam, says that, ‘In the western context, the biggest risk ex-Muslims face is not the baying mob, but the loneliness and isolation of ostracism from loved ones. It is stigma and rejection that causes so many ex-Muslims to conceal their apostasy.’[40]

As with Islam in Britain and elsewhere, the more all-encompassing, widespread and rigid an identity is in one’s world, the more power the administrators of it possess and the more difficulty there is in breaking away from it. But if there are alternative possibilities readily available for involvement and inclusion, the fear of leaving is greatly alleviated. For other identity groups, the issue takes a different shape. It is inconceivable for most people to consider leaving their skin colour or ethnicity or gender. But forsaking identity-based ideology can appear precisely like this, as does giving up one’s identity group, made worse by administrators of identity claiming you are betraying that group, whether it be women or black people or ‘the LGBT community’. Also, while mainstream feminists for example do not administrate much to women as a group (in terms of instructing them how to live), they do administrate on behalf of women and represent them at elite levels of society, notably around institutions of the liberal-left like the Labour Party. For women in these circles, rejecting mainstream feminism is almost inconceivable. It would be an act of betrayal and bring a degree of aggravation which is likely to appear decidedly unattractive. This leaves feminists to dominate public debate about women, in many ways contrary to how the wider female population sees things.

If anything, the disjuncture between British women and feminists is even larger than that between British Muslims and Islamists. Polling conducted by Survation for the feminist pressure group the Fawcett Society in late 2015 showed only nine per cent of women questioned describing themselves as feminist, with 65 per cent instead agreeing with the statement ‘I believe in equality for women and men but I don’t describe myself as a feminist.’[41] These findings replicated those of a smaller survey (and only of its members) conducted by Netmums in 2012, in which only 14 per cent of 1,300 women who responded chose to call themselves feminist, with lesser enthusiasm amongst young women.[42] In the 4,201-women Fawcett sample, only four per cent said they did not know what feminism stands for, yet the organisation’s chief executive Sam Smethers chose to describe the problem as a matter of branding - that both men and women were overwhelmingly feminist but just did not realise it. As she put it, ‘The overwhelming majority of the public share our feminist values but don’t identify with the label. However the simple truth is if you want a more equal society for women and men then you are in fact a feminist.’[43]

The Fawcett-Survation survey showed that women in London tend to have much stronger feminist tendencies. In a 2012 article for the feminist website The F Word, Pavan Amara said, ‘out of 38 women who identified as working-class and were interviewed for this article, all agreed with the statement that working-class women’s voices were not adequately heard within mainstream feminism. Some still considered themselves feminists, others refused to identify as feminists because of a perceived glass ceiling of class and education within the movement itself.’[44]

One of those interviewed said:

I remember once me and a friend from the same area rocked up [to a feminist event] in mini-skirts, high heels and red lipstick. We went because we felt strongly about women’s place in society, but as soon as we walked in they stood there gawping at us like ‘Why are you here?’

We were instantly made to feel unwelcome, but we dressed like that because that’s what all the other girls in our area were wearing at the time. They spoke to us like we wouldn’t understand the political issues they were talking about, and we didn’t really know the vocabulary they were using anyway.

We tried another one in Liverpool, but felt totally fish out of water there as well. Even when we were deciding where to meet, me and my friend said ‘down the pub over a few pints’, and they looked at us with horror.

In its Survation survey, Fawcett focused particularly on issues of concern to feminists themselves, including the attitudes of recruiters to feminism and equality, the access of women to top jobs (the representation agenda) and issues around the fluidity of gender identity. The stand-out example of the representation agenda in action in politics is the Labour Party’s All-Women Shortlists (AWS) for candidate selection (which we explore further in Chapter 6 on Labour as an institution). In 2014 YouGov carried out polling on this, which showed majorities of all social demographic groups opposing this form of favouritism - including women by 51 to 30 per cent and Labour voters by 46 to 40 per cent.[45]

This all adds up to a pretty clear picture in which the principal politics and interests of feminists do not map on to women as a group - unless we abstract out to very general ideas of fairness and equality. The administration of feminists is not meeting with a general giving-way from women, unlike the Islamist administration of Muslim separateness and victimhood. At the same time though, any woman (or indeed man) who publicly rejects these narratives of mainstream feminism will face serious difficulties within liberal-left institutions, including the Labour Party.

For both women and Muslims, and indeed for other identity groups, conformity is so much easier and more convenient. It may bring constraint but with that it brings the connections which make possibilities appear - showing off a version of freedom as involvement rather than individuality. Established identities offer something tangible to fall in, conform and fit in to: an entry into life every day that requires little thought and for which the explanations and justifications are familiar and accepted. For the most part, we simply have to strap ourselves into this pre-prepared world and go along with the ride. The alternative path of questioning and resistance appears tiresome and difficult in contrast, promising rejection and damage to our existing relationships and social status. It holds out the prospect of freedom but also isolation and estrangement from existing connections and the possibilities that flow out of them. The safe and easy option that most of us follow most of the time is to play along, and it is not difficult to see why.

In this way, pre-existing, prescribed identity is convenient not just for those of favoured identity groups but for all of us, because it offers group membership without the need to opt in, so without the need to go out and actually choose something. We find it already before us. There is no signing-in process or ceremony to mark entry to the group; administrators simply need to keep to their scripts and group members need only not resist. Given-away identity works not necessarily through outright support but rather by lack of opposition to authority and the way things are. The stronger and more strictly enforced the authority, the less likely the opposition to it.

In return for the acquiescence that characterises identity as giving way, the system of diversity confers certain benefits: protected or, to use the argot of identity-based activists, ‘safe’ spaces in society. If you qualify with an approved identity, then you are worthy of this protection per se for being who you are, as someone of a protected identity. But without acquiescence, this protection can vanish, since rejecting your identity would mean rejecting who you are as a victim and therefore the need for protection, representation and favouritism - indeed for any involvement in the system. This brings us to a crucial point about the system of diversity: that belonging to a favoured identity group does not confer authority, but protection, which is a specific position in a relationship of power. You must follow the party line or at least acquiesce with it in order to come within its embrace. But to gain authority you must actively appropriate and administrate the universal situation of your group, which means prescribing victimhood to others, along with any more positive elements of group identity, in public situations. Authority and protection do not automatically follow favoured fixed properties. They follow conformity with how those properties are meant to fit in to the world.

The system of diversity depends on this giving way to authority being maintained. For the representatives to represent, the represented must not oppose their representation. They do not have to openly embrace it, but this authority endures only so long as the represented do not challenge it and do not challenge the versions of identity prescribed for them. Conformity works not so much by group members embracing or even choosing to accept this state of affairs but by them not choosing to reject it.

Wider consequences

One of the barriers feminists face in spreading their influence beyond the middle class liberal-left is the difficulty of taking their basic identity group favouritism to its ultimate conclusion through separation and separatism in practice, which would allow them to minister to their identity group without interference from ‘the patriarchy’. Given that men and women share the same homes and have children together, this is not easy to achieve.

In looking at the partial success of Islamists in dividing Muslims from non-Muslims, religious and ideological influence is reinforced by ethnic and geographic dimensions, as many of our Pakistani and Bangladeshi immigrant communities congregate closely together based on kinship ties and communal solidarity. In her review published in 2016, Louise Casey noted how nine of the ten highest minority faith or ethnic group concentrations in Britain in 2001 were Pakistani/Muslim, with all nine of them in the north of England. This feeds over into schooling, with the Department for Education reporting in January 2015 that 511 state-funded schools in 43 local authority areas had 50 per cent or more pupils of Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnicity, with 40 of them having 90 per cent or more - mostly in the same areas identified as having high segregation.[46] As the Bradford Labour MP Naz Shah has said, ‘Now, with the third and fourth generations, it’s perfectly possible to live a life where you never have to speak English because everyone in the shops and services where you live speak your language.’[47]

Religion is an element of this, but not the only one. In her report, Casey picked up on what David Goodhart has called the ‘first generation in every generation’ phenomenon, whereby successive generations in an immigrant community import spouses from their places of origin. She pointed to a University of Bristol study detailing how half of British Pakistanis actually married back in Pakistan, most of them to cousins or other members of extended kin groups. Casey said: ‘It came up regularly in meetings in some areas as a reason for the strong perpetuation of foreign cultural practices and lower levels of English language proficiency. We were told in a review visit that in one northern town all except one of the Councillors of Asian ethnicity (all men) had married a wife from Pakistan.’[48]

However, these marriage practices cannot be cordoned off from religion; indeed they are entwined with it. Casey noted estimates that 70–75 per cent of Muslim marriages in Britain have not been registered under British civil law, which means that these often foreign-born, non-English speaking wives have few if any rights to appeal to.[49] The practice of Sharia law as a parallel legal code helps maintain the authority of religious and community leaders over members of the community in this way, while shielding them from a largely foreign, unknown society outside that can easily be demonised.

But the ethnic-related separation we are seeing in Britain is not restricted to geographical pockets of segregation; it remains a much wider existential phenomenon. We can see it in our school playgrounds where, as the sociologist Richard Sennett has pointed out, schoolchildren from different cultural backgrounds mix happily with each other at the age of six or seven, but ‘by the time they are 14 it is like a chemical separation - no longer speaking to people with different colour and accents. When they have to deal with each other they are at a loss.’[50]

This is not universal of course and many teenagers and young adults mix happily with others of different colour and accents, notably those from the internationalised middle-to-upper class, which can appear quite diverse (especially to itself) while being pretty monocultural. Nevertheless you only have to spend some time in an inner-city town centre after schools have finished for the day to see the phenomenon of separateness at work. We should see this as a process of socialisation: a process of learning to differentiate oneself from others based on skin colour and background. In one sense, we might see it as perfectly normal and natural, but it is difficult not to see it at least partly as the politics of identity and system of diversity at work.

Goodhart says, ‘The new identity politics worked up to a point and certainly helped to create a more confident minority elite. But it weakened the integrationist pulse, especially coming at a time when rising numbers and satellite dishes were making it easier for some minorities to live increasingly apart from mainstream society.’ He adds: ‘At a time when national politicians should have been leaning against the drift towards more segregated communities, for the most part they had nothing to say at all.’[51]

The pressure group British Future conducted polling showing that attitudes to integration vary quite widely between even broadly-defined racial groups. For example, 61 per cent of black people came out against categorising by race or ethnic background, compared to 38 per cent of white people and 43 per cent of those of Asian background. Black Britons also showed up as more interested in integrating into mainstream British society than Asians, who were less keen on mixed-race relationships even than whites.[52]

There are different forces at work here. Some are working towards assimilation and integration, but the politics of identity is working in the other direction, towards separation along the lines of fixed identity. The British-born American academic Kwame Anthony Appiah has written about these latter forces bearing down on him as black and also gay:

If I had to choose between the world of the closet and the world of gay liberation, or between the world of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Black Power, I would, of course, choose in each case the latter. But I would like not to have to choose. I would like other options. The politics of recognition requires that one’s skin colour, one’s sexual body, should be acknowledged politically in ways that make it hard for those who want to treat their skin and their sexual body as personal dimensions of the self. And personal means not secret, but not too tightly scripted.[53]

When the organisers of the Pride in London march decided to ban UKIP’s LGBT group from participating on spurious ‘safety’ grounds in 2015 (albeit after a robust debate), they showed that the standards for entry for being acknowledged as gay are as much about your politics as whether you are gay or not. To qualify as part of the identity in-group, you must give way to the correct political administration.

In institutional life and out into everyday social life, the widening sweep of the system of diversity is politicising fixed identity seemingly everywhere we look; indeed it is becoming a frame through which so many of us and our institutions see the world. For favoured group members, this offers possibilities for belonging and advancement, but it often restricts the scope of possible alternative ways of involvement. Clearly among some of the groups politicised, including women and black Britons, separatist politics of identity have a relatively limited impact, albeit they still have a noticeable influence in the school playground and in political life. But for others - notably those British Muslims living in communities increasingly segregated by ethnicity and religion - politics, community and fixed identity have fused to a great extent, aided by one form of integration with the wider ‘mainstream’ society: into the system of diversity.

1 Tweet from @MoDawah, 27th February 2016, 1.52pm.

2 ‘Charlie Hebdo given “Islamophobe of the Year” award’, The Independent, 11th March 2015.

3 ‘About IHRC 2’, video from IHRCtv, 23rd August 2010.