The New York Times obituary written by Margalit Fox and published November 20, 2007, truly captured the essence of Mary Walker Phillips and the importance of her contribution to knitting.

Mary Walker Phillips, a prominent textile artist, took the utilitarian craft of knitting and gave it bold new life as a modern art form to be displayed on the walls of museums around the world.

For centuries, knitting was a homey pastime, ideal for making sweaters, socks and hats. It was less a creative art than a re-creative one: women—for it was nearly always a woman who wielded the needles—typically worked from printed patterns, following a set of instructions to produce a finished garment of predetermined design and dimensions.

By the mid-20th century, other textile traditions, like weaving, had crept into the realm of fine art, hung in galleries and reviewed seriously by critics. But knitting, consigned to the hearth, lagged far behind.

What Miss Phillips did, starting in the early 1960s, was to liberate knitting from the yoke of the sweater. Where traditional knitters were classical artists, faithfully reproducing a score, Miss Phillips knit jazz. In her hands, knitting became a free-form, improvisational art, with no rules, no patterns and no utilitarian end in sight.

Traditional materials also went out the window: where garment knitting generally involves wool or cotton, Miss Phillips’s huge, abstract, diaphanous hangings might also use linen, silk, paper tape or fine metal wire. They sometimes incorporated materials like bells, seeds and bits of mica.

Considered one of the two or three most influential knitters of the second half of the 20th century, Miss Phillips was a fellow of the American Craft Council, an honor bestowed on only the most distinguished artisans. Exhibited worldwide, her work (which also includes avant-garde macramé) is in the permanent collections of major museums including the Museum of Modern Art, the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Mary Walker Phillips was born in Fresno on Nov. 23, 1923, to a prominent family descended from California pioneers. A traditional knitter in childhood, Miss Phillips—to the end of her life, she preferred “Miss”—began her artistic career as a weaver. After studying at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, she worked in San Francisco and Switzerland, weaving fabric for clothing, upholstery and table linens. She later opened her own studio in Fresno.

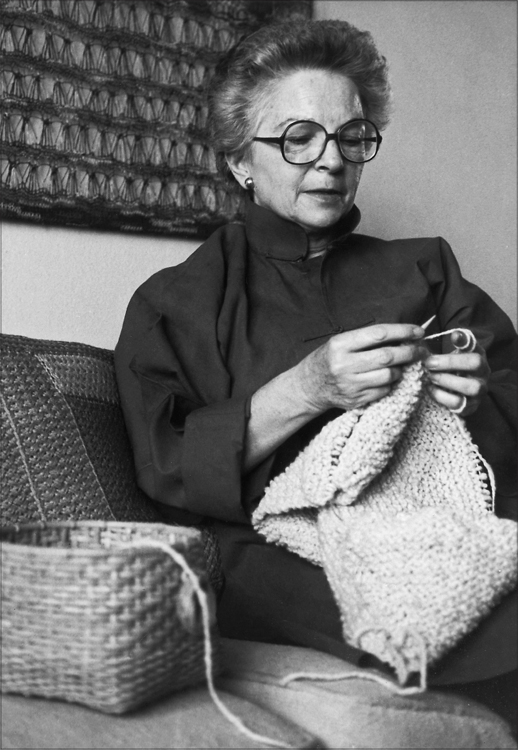

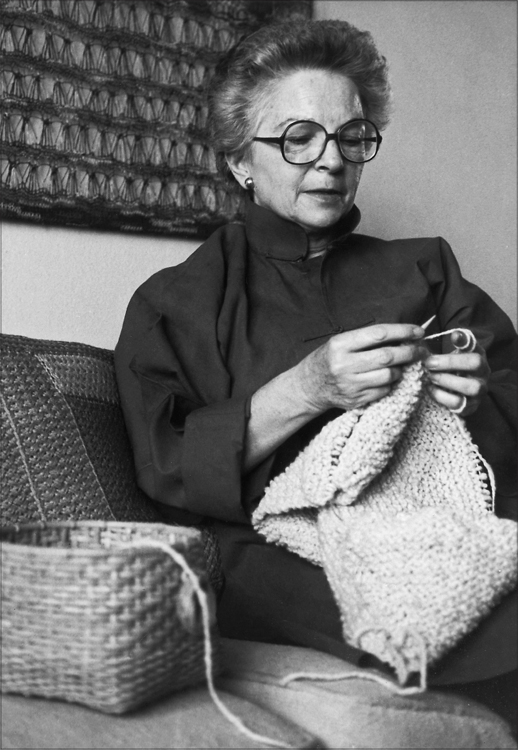

Mary Walker Phillips, 1985. (Photograph by Glenda Arentzen.)

Just how accomplished Miss Phillips was at the loom can been judged from a telegram she received in April 1948: “Kindly bring cotton material for weaving thirty five yards drapes natural deep rose lavender and dark brown, also gold metallics.”

It was signed “Mrs. Frank Lloyd Wright.” Miss Phillips spent three weeks at Taliesin West, the Wrights’ home in Scottsdale, Ariz., weaving the family’s drapes and tablecloths.

In 1960, Miss Phillips returned to Cranbrook, completing her bachelor’s degree and, in 1963, earning a master of fine arts, concentrating in experimental textiles. Around this time, a friend, the noted fabric designer Jack Lenor Larsen, suggested she experiment with knitting as a medium for contemporary art.

Miss Phillips, who settled in New York in a yarn-filled apartment on Horatio Street, took up her needles once more. But what sprang from them was like no knitting ever seen. Using techniques that went beyond traditional knit and purl stitches, she created pieces that looked like delicate tapestries or vast expanses of lace, with transparent latticework, open areas and whorled textural patterns. Hung away from the wall and lighted well, her work threw off a dramatic counterpoint of shadows.

“Rocks and Rills,” wall hanging, 14″ × 20″, (1966). Linen. Beach pebbles in Double Knit Pockets, Bobbles, Plaited Basket, Knit into the Stitch Below, Horizontal and Ladder Stitches.