The bubonic plague or Black Death that killed half the population of Europe between 1346 and 1353 didn’t affect animals. Receding, it left vast tracts of woodland teeming with game. First for the kitchen, then for sport, landowners led packs of hounds in pursuit of wild boar, hares and deer. Trained hawks swooped on pheasants, partridge and grouse. Carp and trout were netted from freshwater streams. Chasing and killing animals offered some of the excitement of war, even a little of the danger, with the bonus that, once the hunt ended, the quarry could be turned into food that not only tasted good, but, in the manner it was served, reminded the diners of how it had been acquired. Each meal was one more moment of pleasure snatched from eternity.

To preserve the exclusivity of hunting, poaching on royal preserves was punishable by mutilation or death. Peasants who risked being blinded simply for stalking an animal were bitter that hunters could summon them at all hours to act as beaters. It was even known for noblemen who felt the cold to order serfs to defecate in a heap, then immerse their feet in the steaming pile to warm them.

The aristocracy devoted much time and effort to maintaining a countryside well-populated with creatures to hunt. “Seasons” protected animals and birds while they were mating and rearing their young. Gamekeepers raised pheasant, partridge and grouse in captivity and restocked woodland that had been “hunted out.” Such dates as August 12, known in Britain as “the Glorious 12th,” marking the opening of the shooting season for grouse, were red-letter days for the gentry; renewals of their license to slaughter.

Originally, all hunting was called “venery” and all meat from hunted animals classed as venison, but the definition narrowed as deer became the most popular game and their meat correspondingly valued. As “venison” came to mean only deer meat, the French coined a new word, gibier, to define any creature that lived free in water or the open air, and could therefore be honorably hunted.

But food was only a by-product of the hunt. The primary motive was sport, and the prey, in particular foxes, wolves or bears, often chosen for cunning and speed rather than culinary possibilities. As Oscar Wilde scoffed at fox hunting, it was a case of “the unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable.” How one behaved during the hunt also counted for more than a successful kill. Etiquette required that the gentleman hunter not show excessive zeal or expertise, for example, by outrunning the pack or beating the hunt master to the kill. In Isabel Colegate’s novel The Shooting Party, a lord taking part in a private shooting competition at a country house party in 1913 is exposed committing the ultimate transgression—target practice.

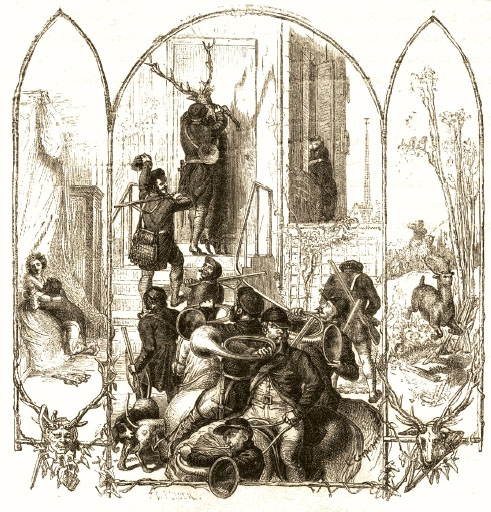

Hunting provided one of the few occasions in which a nobleman left home. Once gone, he was absent for the entire day, and might even stay out overnight, an opportunity for the women he left behind to explore other diversions. Venery, coined to describe hunting, acquired an additional meaning: the pursuit of sexual satisfaction. Infidelity was so common in the hunting society that a man with an unfaithful wife was signified by showing him with a pair of horns, a reference to the fact that, when a stag lost to another in combat, the winner acquired the loser’s mate. The illustration to La Double Chasse (The Double Hunt), an 1839 poem by Pierre-Jean de Béranger, shows a hunt forming in front of a chateau. As the master and his cronies hoot on their horns, eager to be off, the lady of the house sneaks her lover through a window and some jokers slyly hang the antlers of a stag on the master’s front door.

Blood was the avatar of every hunt, the symbol of a readiness to kill. The faces of boys on their first hunt were ritually smeared with blood. Medieval stories of the hunt often include the figure of the professional huntsman, a commoner ready to kill at the orders of his master. In the traditional fable of Snow White, the queen sends such a man into the woods with orders to murder her, although, atypically, he relents. Another legend, adapted by Carl Maria von Weber for his 1821 opera Der Freischütz (The Free Shot), transformed the character of Samiel, the Archangel of Death who led the revolt of the angels against God, into the Black Huntsman of the Wolf’s Glen, who exchanges the soul of the main character for a rifle that cannot miss.

Illustration to La Double Chasse (The Double Hunt)

The most vivid legend associated with hunting is that of the Wilde Jagd or Wild Hunt. Originating in Scandinavia as a hunt led by the god Odin or Woden, it took root in medieval European mythology as a manifestation of the horror that stalked the choked and overgrown woodland of the Dark Ages. Thundering over the treetops and plunging through the forest at impossible speed, the riders of the wild hunt, at the heels of a hunting pack of wolves, were thought to warn of war or plague. People in its path would be trampled, or, in some versions, whirled up in the wake of the phantom riders. In other manifestations of the myth, simply to look upon the hunt was certain death.

Having designated the hunting and eating of game as their monopoly, the gentry emphasized the fact in art. Craftsmen preserved the hide, horns, claws and heads of their kill. Skins and furs became clothing, and antlers were mounted in places of honor. Later, stuffed and mounted trophies of the hunt were supplemented by animalier bronzes: statuettes of game birds, hunting dogs, horses and wild boar.

Paradoxically, the first Europeans to create graphic art from the hunt were men of God. From the abbeys where they had preserved culture during the Dark Ages, monks of the 15th century watched as hunting parties rode out for a day’s sport. Turning back to the manuscripts they were painstakingly copying and illustrating, some put aside the pious but dull images of planting and the harvest, and exercised their imagination instead with visions of pheasants exploding from the brush, hawks whirling in the air and brilliantly dressed ladies and gentlemen enjoying a few hours of sunshine and blood.

Halt During the Hunt, Charles-André van Loo, 1737, Musée du Louvre