The feast, a rare experience for the peasantry, took place daily in palaces such as Versailles. From the moment servants woke the king and queen at 7:30 a.m. with tea or hot chocolate to the time they retired about 11:30 p.m., the royal family would eat, or at least be offered two main meals, at 10 a.m. and 4 p.m., each of 20 dishes or more, as well as snacks they could slip into their pockets in case they felt peckish.

To wash down this rich diet, the king drank only champagne, water generally being polluted, and other beverages, such as chocolate, suspect. In October 1671, Madame de Sévigné, a member of Louis’s court and a tireless gossip, wrote to her pregnant daughter.

But what do you have to say about chocolate? Are you not afraid of how it can burn the blood? What if all the effects that appear miraculous mask some sort of diabolical combustion? What do your doctors say? In your fragile state, my dear child, I need your word [that you will not drink it], because I fear that you will suffer these problems. I loved chocolate, as you know. But I think it did burn me; and furthermore, I have heard many terrible stories about it. The Marquise de Coëtlogon drank so much chocolate when she was pregnant last year that she gave birth to a baby who was black as the devil and died.

Chocolate, only recently introduced in France, via England, competed with the equally rare Chinese tea as the preferred nonalcoholic drink of the aristocracy. Initially it was credited with curative qualities, and taken as medicine. For the more familiar modern form of chocolate, as a solid, we have Marie Antoinette, the queen of Louis XVI, to thank. Disliking the taste of her morning medication, she asked her court pharmacist, Sulpice Debauve, to make it more palatable. Mixing the drug with chocolate, cane sugar and almond milk, he pressed it into coinlike discs called pistoles, each printed with the three gold lilies of the Bourbon monarchy—the ancestor of today’s chocolate bar. One of the few courtiers to survive the revolution of 1789, Debauve opened a Paris shop in 1800, selling chocolate in all its forms from the same Paris premises on Rue des Saints-Pères where his descendants still do business.

The Cup of Chocolate (The Penthièvre Family), Jean-Baptiste Charpentier, 1768, Musée de l’Histoire de France, Château de Versailles

A feast at one of the great châteaux of France during the 16th century fell somewhere between meal and show. As well as musicians who played and jesters who did tricks, the kitchen would periodically serve some elaborate creation, aimed at impressing the guests with the wealth of the host and the expertise of his cooks. These grosses pièces could include spit-roasted pheasant, duck, fish and, on special occasions, swan or peacock, served in their plumage. Depending on the skill of the chef, guests might also be invited to eat such jeux d’esprit as “meat fruit”—apples, pears and plums, convincingly molded from raw minced pork and colored to look like the real thing.

Made for display as much as to eat, the grosses pièces were difficult to carve, so an “esquire carver” was put in charge. This role, allocated to a favored courtier or distinguished guest, carried considerable prestige. Flourishing his sword, the carver slashed open the carcass, skewered the tastiest morsels and transferred them to the host’s dish. Over time, the role became largely ceremonial. At Versailles, where he was known as Controller of the King’s Pantry, the occupant of the office no longer touched the food. Accompanying dishes from the kitchen, he stood by with a sword while the royal family ate. Such positions changed hands for large sums, but the money was well spent. From what he observed while holding the post at Versailles under the free-spending Louis XV, playwright Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais wrote The Barber of Seville and The Marriage of Figaro, classic views of the aristocracy as seen by their servants. Beaumarchais found Louis an inviting target for satire. “There was nothing he liked so much as flattery,” wrote the Duc de Saint-Simon, “or, to put it more plainly, adulation. The coarser and clumsier it was, the more he relished it.”

To feed the thousands of courtiers surrounding the king and his nobles, chefs augmented game with saltwater fish, oysters and lobsters, and pies and pastries made from the meat of hares, deer and wild birds. The “four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie” of the nursery rhyme was no invention. Woodcocks, larks, thrushes, robins and cranes were all prized, as were pigeons. Servants stalked the roosting flocks at night, dazzling them with burning torches while they clubbed them to the ground, the subject of a striking 1874 painting, Chasse des oiseaux avec les feux (Hunting Birds With Fire), by Jean-François Millet.

Quail were also popular. A page from one of the most important Gothic manuscripts, created between 1412 and 1416 for John, Duke of Berry, shows the duke celebrating the New Year with heaped dishes of roasted quail, obviously meant to be eaten with the fingers. Successive generations of cooks developed new recipes for this delectable bird. By adding fruit, caille aux raisins (quail with grapes) tenderized its sometimes tough and dry flesh. For the more complex cailles en sarcophage (quails in a sarcophagus), the birds were boned and baked in a shell of puff pastry with truffles and foie gras. Danish writer Karen Blixen resurrected this long-forgotten dish, a speciality of Paris’s Café Anglais, for her 1950 short story Babette’s Feast, made world-famous by Gabriel Axel’s Academy Award-winning 1987 film adaptation starring Stéphane Audran.

Bird’s-Nesters, Jean-François Millet, 1874, Philadelphia Museum of Art

The more rare the bird, the more exotic the recipe. Ortolans, no bigger than a thumb and too tiny to shoot, were trapped in a mist net, drowned in cognac, roasted in a closed casserole and eaten whole, including feathers, head and feet. As larks were noted for their song, chefs served their tongues separately, cooked, since their sound was “sweet,” in honey. The remaining meat became pâté, a particular favorite of American food writer M.F.K. Fisher. Reminiscing about her days in post-World War II France, she wrote, “There was always that little rich decadent tin of lark pâté in the cupboard if I grew bored.”

Royal dinners ended with mignardises: sweet cakes, nuts coated in candy or fruits preserved by boiling in sugar. One of the earliest depictions of confectionery is in the 15th-century French hangings known as The Lady and the Unicorn, each tapestry illustrating one of the five senses. To convey the sense of taste, the lady is shown selecting a sweet from a dish offered by her maid, while a monkey at her feet nibbles on one it has stolen.

Anything sweet was generally flavored with honey. Sugar, like salt, was valued as a preservative, and taxed accordingly. (The levy on salt alone brought in six percent of France’s total revenue.) Difficulties in refining and transporting cane sugar from the West Indies inflated its price to a level comparable to such spices as nutmeg, ginger and cloves. It remained there until the means were discovered at the start of the 19th century to extract sugar from beets.

The Lady and the Unicorn “Taste,” between 1484 and 1500, Musée de Cluny in Paris

Ritual dominated eating at Versailles and other palaces. Meals arrived at the table in waves of a dozen or more dishes at a time. Called service à la française (French service), this system survived until the early 19th century, when, largely at the instigation of the great chef Marie-Antoine Carême, it was supplanted by Russian service (service à la russe), in which each diner received a portion of the dish individually and at the same moment, a reflection of the fact that the czars had enough serfs to serve even a hundred guests simultaneously.

The tables on which royalty dined were generally oval or round. Favored courtiers sat close to the king and queen, and shared their privileged access to the food, while those farthest from the royal presence had to grab what they could. Everyone but the king wore full court dress at table, including a hat, and no dish could be touched until the king served himself. Dishes of salt were placed conveniently close to the king and his favorites. The remaining diners, in a phrase that came to mean anyone deprived of preference by reason of class, were considered “below the salt.”

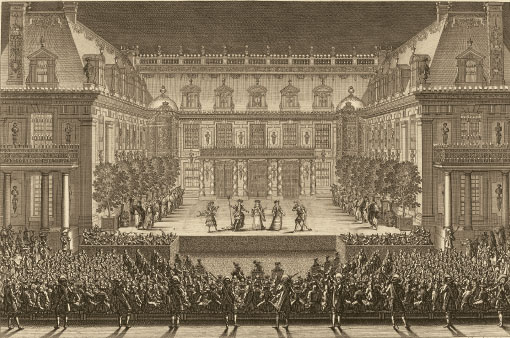

The king’s feasts culminated in lavish entertainments. During his 72-year reign, Louis XIV, known as “The Sun King” for the lavishness of his court, commissioned more than 300 works of art, many documenting his leisure activities, including the hunt. Three thousand courtiers lived in and around the Palace of Versailles, including the playwright Molière and composer Jean-Baptiste Lully. (In a rare case among musicians of a work-related fatality, Lully, who beat time with a heavy staff, brought it down on his foot. The wound became infected, and he died of blood poisoning.) His banquet and events manager, the Officier de Bouche (Master of the Mouth), was required not only to feed as many as a thousand guests but also stage the accompanying spectacles. Festivals could last for days. Fireworks were commonplace, but Versailles went one better. At sunset, its gardens erupted with fountains. Water spouted, gushed and bubbled, artfully lit to show off the ingenuity of the royal engineers and the landscaping of André Le Nôtre. Musicians played pieces composed specifically for the spectacle, and for masques, in which performers, often including Louis himself, dressed in sumptuous costumes to dance and act out a mythological story.

Festivity given by Louis XIV, at Versailles in 1674. Performance of the opera Alceste by Lully and Quinault, Jean Le Pautre, 1676