The golden age of restaurants began with the Revolution of 1789, when chefs de cuisine who had served the great houses of France found themselves out of work, and set up in business for themselves. Before then, travelers ate at inns that offered a plate of whatever the owner’s wife had prepared that day; usually pottage, with bread and beer, which was eaten at a common table. Others brought food from home or, when passing through a town, purchased bread, smoked meat, cheese and beer from a boulanger, charcutier, fromager and brasseur, eating them at the roadside.

Despite rival claims on behalf of Roze de Chantoiseau, who was running an establishment near the rue St. Honoré in 1773, France’s first restaurateur is long believed to have been a M. Boulanger, who opened for business in 1765 on the corner of rue Bailleul and rue Pouille (today’s rue du Louvre). He offered mostly bouillons, designed to restaurer or restore the weary traveler. An inscription by the door promised, “Boulanger débite des restaurants divins” (Boulanger provides divine restoratives). Some reports mention an additional quotation in Latin paraphrased from the Bible: “Venite ad me omnes qui stomacho laboratis et ego vos restauro.” (Come to me those who are famished, and I will restore you.)

The luxury of choosing from a number of dishes, or sitting indoors at separate tables rather on a common bench, and enjoying the attention of competent waiters, including, apparently, Boulanger’s pretty wife, was new to French culture. Encouraged, Boulanger was said to have introduced dishes other than soup, including “salted poultry and fresh eggs,” and lamb’s feet in white sauce, a precursor of pieds d’agneau sauce poulette, a sophisticated dish by any standards. Some accounts even have Boulanger standing in front of his establishment, dressed like a gentleman, complete with sword, and encouraging pedestrians to step inside.

Despite this accumulation of detail, recent research has cast doubt on the very existence of M. Boulanger. No contemporary source mentions him or his establishment. But whether he existed or not, the institution he represented had come to stay. Dismissing protests from shopkeepers of the food guilds who regarded them as unfair competition, in June 1786 the Provost of Paris issued a decree according restaurants legal status, authorizing them to offer meals until 11 in the evening in winter and midnight in summer.

The Corner of the Rue Bailleul and the Rue Jean Tison, 1831, Thomas Shotter Boys, Musée Carnavalet

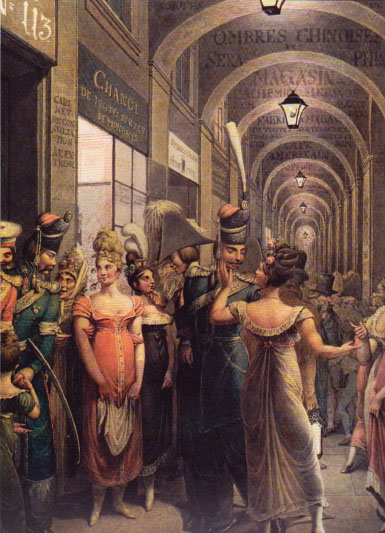

The same year, Antoine Beauvilliers, former chef to the Count de Provence, opened the Grande Taverne de Londres. At mahogany tables with linen tablecloths, under crystal chandeliers, efficient waiters served diners from an extensive menu and wine list. Since, then as now, “location, location, location” were the first rules of any business, Beauvilliers shrewdly chose to open at the Palais-Royal. Situated just opposite the Louvre, the Palais was famous, indeed notorious, for its large formal gardens and a surrounding arcade that sheltered shops, gambling rooms and a floating population of petty criminals, political plotters and prostitutes.

Today, the only surviving restaurant of any age at the Palais-Royal is Le Grand Véfour. Opened in 1784 as the Café de Chartres, it was purchased in 1820 by Jean Véfour, who gave it his name. Brass plates set into the tabletops record some of the celebrities who ate there, ranging from novelist Victor Hugo and gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin to Napoleon Bonaparte and his empress, Josephine. Cross-dressing novelist George Sand was such a regular customer that the restaurant made a cast of her hand to create its ashtrays. The aging Colette, who lived nearby, was regularly carried down the stairs to dine there, often with her neighbor Jean Cocteau, who designed its menus.

The working class of urban Paris seldom patronized restaurants, preferring street vendors who sold coffee, hot milk, bread, soup, roast potatoes and stew. Around noon on weekdays, pop-up restaurants appeared. Firing up stoves in otherwise empty stores, women prepared a few basic dishes which one could eat there or take away. Writing in 1899, Georges Montorgueil described one such woman:

There she kept her eye on her pot au feu (beef and vegetables in broth) while peeling the potatoes that sizzled in boiling fat—the same fat that served to deep-fry a sole, or cheese puffs and donuts. A sign proposed “Soup and Beef To Go.” For two sous, you got a bowl of hot beef broth; for four more, you could choose between stewed beef, mussels, boiled potatoes—and always, naturally, the classic frites.

Le No. 113, Palais-Royal, Georg Emanuel Opitz

For those who preferred cold cuts, triperies offered cooked tongue and tripe. Charcuteries sold ham and sausage, all of which could be eaten on the run, as could bread still warm from the oven. Young men and women still nibble the end of a baguette as they check their smartphones while walking back to the office, and a sandwich jambon fromage—ham and Gruyère cheese on a baguette—remains the most popular lunchtime snack.

Artists of the 16th century such as Titian and Giorgione celebrated the French landscape by showing gods and goddesses, nymphs and shepherds enjoying the pleasures of the countryside, usually in the form of the fête champêtre, an elaborate court picnic, with courtiers in fancy dress, an orchestra hidden in the trees and a lavish buffet lunch. When the Impressionists at the end of the 19th century took art out of the studio and began painting en plein air, they revisited such paintings, but with a sarcastic edge. For his 1863 Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Lunch on the Grass), Édouard Manet copied a composition from Raphael. Two men and two women recline in a forest setting, the men fully clothed, with one woman nude and the other, half-dressed, wading in a pond. Setting out to jar his audience by mixing classical form and modern sensibility, Manet distorted the proportions and perspective, giving the impression of an outdoor scene recreated indoors. The remains of a picnic add the last incongruous touch. The gods of Poussin and Giorgione would never have lowered themselves to snack on bread and cheese.

Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Lunch on the Grass), Édouard Manet, 1862-63, Musée d’Orsay

Pierre-Auguste Renoir shared the common enjoyment of picnics, but painted them to emphasize their social rather than culinary pleasures. For his 1875 Déjeuner chez Fournaise (Lunch at Restaurant Fournaise), and the famous 1881 Le Déjeuner des canotiers (Luncheon of the Boating Party), he reproduced scenes at the Restaurant Fournaise at Chatou, a short boat ride along the Seine. In 1936, Jean Renoir, the painter’s filmmaker son, directed Une partie de campagne (A Day in the Country), a 40-minute adaptation of a story by Guy de Maupassant about a naive shopkeeper and his son-in-law who succumb to the pleasures of an afternoon by the river, the men sleeping off their lunch while the wife and daughter surrender to the sensual attentions of two young city gents. As in Manet’s canvas, the apparent innocence of a picnic is subborned by hints of classical abandon, one young man imitating a capering pipe-playing Pan as he lures the complaisant matron into the undergrowth.

In 1959, Jean Renoir enlarged on this theme in his fantasy of the near future, also called Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Lunch on the Grass). To publicize his views that artificial insemination should replace sex, a radical biologist stages a country picnic to announce his plans. Filmed around Cagnes-sur-Mer and at Les Collettes, the estate where Pierre-Auguste Renoir spent his last years, the film celebrates all the animal pleasures, not least those of eating and drinking en plein air. In adding a goat-herding Pan figure who can impose chaos with a few notes on his pipes, Renoir follows his father in sweeping away the social conventions associated with life lived in the open. “Invaded,” in Renoir’s words, “by far from scientific emotions,” the biologist discards his convictions when he sees a beautiful peasant girl bathing in the nude and is seized with the desire to impregnate her.