King Henry IV is famous for having promised his subjects at least one good meal a week. “Si Dieu me prête vie,” he said, “je ferai qu’il n’y aura point de laboureur en mon royaume qui n’ait les moyens d’avoir le dimanche une poule dans son pot!”(“If God gives me life, I will make sure that no peasant in my realm will lack the means to have a fowl in his pot on Sunday!”) Specifying poule and pot was significant. Listeners would have understood that, in speaking of a bird cooked in a pot rather than on a spit, and a poule or hen rather than a poulet or chicken, Henry wasn’t referring to a tender roasted bird but rather to an old fowl which, after a life of laying, became the basis of soup.

Lacking the ovens and spits found only in great houses, peasants cooked at the hearth, usually in an iron pot suspended over coals. During hours of simmering, even the toughest bird dissolved into the rich stock known as bouillon, without which no soup deserved the name. Adding cabbage, dried beans, turnips, carrots, potatoes and a handful or two of barley, the country wife made a soup substantial enough to feed an entire family. Rather than waste a drop, many followed the custom of chabrot, pouring a glass of red wine into the dregs to swill out the last morsels, a habit in part blamed for France’s ubiquitous alcoholism.

At a time when bread was known as “the staff of life,” bouillon, both food and medicine, was regarded as its blood. “I live on good soup, not on fine words,” said the playwright Molière. Scottish writer Tobias Smollett, traveling in Provence in the 1760s, was offered bouillon as a treatment for tuberculosis. Locals swore it contained enough food value to revive even a man who’d been hanged.

The quality of bouillon lay in bones. Discarded by butchers, these were collected by provident cooks who baked them to drive the fat from the marrow, aromatized them with onions and garlic, then simmered them for hours to create a rich and nutritious stock. To skimp on this foundation, diluting or adulterating it, was an offense not only against taste and hospitality but also health. Honoré de Balzac in his 1842 novel La Rabouilleuse (The Black Sheep) sneers at a cheap host who begins a meal with “a bouillon the clarity of which announced it had more quantity than quality.”

Cooking in a pot from Le Christ chez Marthe et Marie (detail), Jos Goemaer, c. 1600

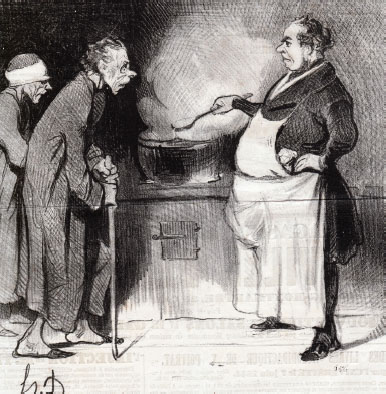

Honoré Daumier, the most gifted and acerbic of France’s 19th-century satirists, also dealt with this unglamorous topic. Two of his images captured the importance of bouillon in the lives of the poor. The first showed a Soupe Populaire, one of the charity kitchens set up to feed the needy. An obese cook contemptuously ladles out soup for two emaciated and bandaged clients who complain of its weakness. Where are the bones that give it nourishment? With straight-faced sarcasm, the cook explains the only bones he could find were domino plaques which, before the arrival of plastics, were carved from bone or ivory. He’d thrown in an additional half set of plaques since the day before, he claims, plus a double six to improve the color.

The second image, called simply La Soupe (The Soup), is among Daumier’s masterworks. A woman and a man share a wooden table, each hunched over a dish. Indifferent to one another, they spoon up their soup with single-minded need. By showing the woman with a baby at her breast, Daumier emphasizes that soup is the mother’s milk of the nation.

Like cheese and wine, soup developed regional variations. Consommé, the broth drunk by the gentry, had a refined flavor but little substance, and was intended to stimulate appetite rather than satisfy it. By contrast, garbure, a specialty of the Gascon country of the southwest, combined bouillon with vegetables and a variety of meats, usually smoked or salted, to create something between soup and stew. In Provence, pistou, a paste of pine nuts pounded with cheese, olive oil and basil, was stirred into the soup, while farther south, along the Mediterranean, fishermen improvised bouillabaisse, a seafood soup, based on a bouillon or fumet made from the shells of crabs and shrimp, into which they tossed any fish too bony or ugly to sell.

Soupe Populaire, Honoré Daumier, 1844

To stretch a soup, cooks incorporated bread, ranging from croutons, the small squares of toast traditionally served with consommé, to the thick slices covered in grilled Gruyère cheese so important an ingredient of soupe à l’oignon. This speciality of Paris’s Les Halles market gave energy to its laborers, known as forts or strong men, but also appealed to socialites who, worn out with partying, dropped by in the small hours for a reviving bowl at one of the market’s all-night cafés.

La Soupe, Honoré Daumier, 1865

Soup reached a peak of refinement under the great chefs of the early 20th century, notably Georges Auguste Escoffier. To make his soupe à l’oignon, from acquiring the beef bones for the basic bouillon to serving the finished soup with its cheese topping still sizzling from the grill, took three days. He proposed the recipe confident that any well-managed restaurant or hotel kitchen would employ a sous-chef specifically to prepare bouillons of chicken or beef and keep them simmering at the back of the stove. Such a kitchen would have no trouble preparing, for example, his Consommé Royale, for which the chef beat some eggs with cream, poured the mixture into molds, poached it until firm, then cut the omeletlike solid into strips. Placing a few of these in a soup bowl with thin slices of chicken breast, mushroom and truffle, he’d ladle hot chicken consommé on top—a soup literally royal, and fit to be served to a crowned head.