In Love and Death, his 1975 pastiche of Tolstoy’s novel War and Peace, Woody Allen pokes fun at Napoleon. Even as he takes possession of Moscow, the emperor frets about his heritage. In particular, he dislikes the pastry his cooks intend to call a Napoleon. “It should have more cream between the crust,” he complains, “and no raisins! If this pastry is to bear my name, it must be richer; more cream.”

The gâteau about which Allen joked, a triple sandwich of crisp puff pastry filled with sweet cream or custard, does exist, but is called a Napoleon only in Anglo-Saxon countries. To the French, it’s a millefeuille, the cake of a thousand leaves. Nor does it date from the time of Napoleon. The Neapolitan, a similar pastry, had already existed for a century. The only foodstuff specifically named for Napoleon is a grade of brandy. Known as XO (extra old), the term designates a blend that has been stored for at least 10 years. He was also commemorated during the 1920s by the Napoleon cocktail, a blend of gin with dashes of the bitter digestif Fernet-Branca, the apéritif Dubonnet and the citrus liqueur Curaçao.

Although he famously said “an army marches on its stomach,” Napoleon had little time for food. Trained as a soldier, he looked on food as fuel, not fun. From paintings and the memoirs of his intimates, we know he was far from the ideal dinner companion. He often arrived at the table late, and ate quickly, racing through a meal in 15 minutes, grabbing whatever was closest. If that happened to be a dessert, he consumed it even before the soup. “Everything ends up in the same place,” he said.

Meals were further complicated by his habit of arbitrarily rotating members of his inner circle in and out of favor. A favorite of one week would, for no obvious reason, seem to irritate him the next, while another won his approval, until that person in turn also lost his confidence. The technique, which kept his intimates off balance, competing to please him, didn’t improve their digestion.

Napoleon’s chronic gastritis dictated dishes without spice or rich sauces.

He preferred potatoes, beans and lots of bread, which he dunked in soup or used to mop up gravy. Anxious to satisfy his every whim, his cooks served a range of dishes, hoping one would tempt him. According to one of his valets, breakfast, the most important meal of the day, could include “boiled or poached eggs, an omelette, a small leg of mutton, a cutlet, a filet of beef, broiled breast of lamb, or a chicken wing, lentils, [or] beans in a salad.”

Dinner was more elaborate, the table more abundantly served, but he never ate any but the most simply cooked things. A piece of Parmesan or Roquefort cheese closed his meals. If there happened to be any fruit, it was served to him, but if he ate any of it, it was but very little. For instance, he would only take a quarter of a pear or an apple, or a very small bunch of grapes. What he especially liked were fresh almonds. He was so fond of them that he would eat almost the whole plate.

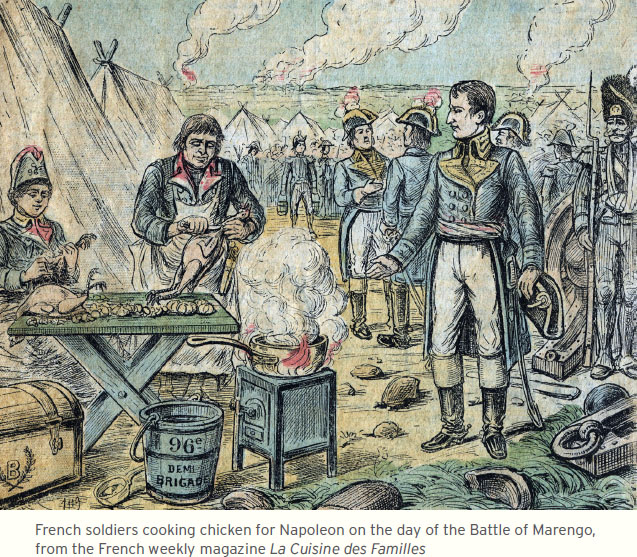

His cooks, of which he used up 11 in the course of his military career, struggled to create dishes suited to his delicate stomach. According to legend, after the battle of Marengo on June 14, 1800, at which the young Napoleon defeated the forces of Italy, his chef, Dunand, searched nearby houses for fresh ingredients. Finding a small chicken, some freshwater crayfish, mushrooms, eggs, garlic and tomatoes, he cut up the chicken, sautéed it with garlic, added tomatoes and mushrooms, and garnished the dish with fried eggs. Enthusiastically received by Napoleon, “Chicken Marengo” became a regular feature at his table, and, in the eyes of the emperor, a lucky one. When, on one occasion, Dunand omitted the crayfish, the emperor protested, “You will bring me bad luck!”

Like many tales about Napoleon, this one has been debunked. Dunand was in Russia at the time of Marengo and didn’t join the Imperial staff until 1801, nor did he record details of this recipe until 1809. Napoleon’s dinner on the night after Marengo was not cooked by Dunand. Instead, the Emperor, hearing that one of his marshals, François-Étienne Kellermann, was about to enjoy a meal provided by a monastery, sent his cook to commandeer it.

Satirists attacking the ruling classes in France often did so in terms of food. Louis XVI was parodied for his gluttony, while Napoleon’s greed for territory gave British cartoonist James Gillray the idea for the 1805 cartoon known as The Plumb-pudding in Danger or State Epicures Taking un Petit Souper. When the British prime minister, William Pitt, was rumored to be considering a treaty with Napoleon, Gillray showed the two leaders at table, dividing the globe like a pudding, with Pitt getting the oceans and Napoleon the land.

Napoleon may not have enjoyed eating but he understood food’s seductive power. In 1804, he asked his closest adviser, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, to transform his family chateau of Valençay into a country retreat for high-level political meetings. A true gourmet, Talleyrand, famous for his comment, “Show me another pleasure like dinner which comes every day and lasts an hour,” chose as his chef the famous pâtissier Marie-Antoine Carême, but first set him a test: Create a year of menus, never repeating a dish, and using only seasonal produce. Carême succeeded with ease.

The Plumb-pudding in Danger or State Epicures Taking un Petit Souper, James Gillray

News of Napoleon’s disastrous 1812 invasion of Russia appalled Carême. “One hundred thousand men dead,” he said, “and 50 chefs!” Many members of the various noble households were friends, among them Laguipierre, chef of the Élysée Palace, who froze to death during the retreat.

Talleyrand foresaw the emperor’s downfall, and planned accordingly. As Czar Alexander I rode into Paris after Waterloo, he was cheered as the savior of France. While his troops pitched their tents under the trees of the Champs-Élysées, he wondered where to make his headquarters, particularly since it wasn’t clear who was to be the new head of state. His advisers favored the Élysée Palace, Napoleon’s former residence, until an anonymous note arrived, warning that the building was mined with explosives.

At the same time, Talleyrand invited Alexander to enjoy the hospitality of his home, not to mention the pleasures of his table. The czar accepted, and was so impressed by the food that, when he returned to St. Petersburg, he offered Carême the choice of becoming maître d’ to his household or his head chef. As for the note, it was found to be a hoax—with either Talleyrand or Carême suspected as the culprit.

In Woody Allen’s Love and Death, Napoleon is also worried about competition: “My spies tell me that my illustrious British enemy is working on a new meat recipe he means to call Beef Wellington.” Though one of his cooks sneers, “It will never get off the ground,” Beef Wellington, also known as boeuf en croûte, a filet of beef baked in a pastry crust, did become a staple of haute cuisine, but not for any reason connected with the Duke of Wellington. Of the stories circulating about the source of this dish, the most credible links it not to the victor of Waterloo but to the city of Wellington in New Zealand.

The same Wellington claims credit for another celebrity dish, the dessert known as the Pavlova. Supposedly created to celebrate the Russian ballerina’s 1926 tour of Australasia, this shell of meringue filled with whipped cream and fruit belongs to a tradition of desserts inspired by divas. In 1893, when Australian soprano Nellie Melba worried that the ice cream she enjoyed might chill her vocal cords, master chef Escoffier, who had already accommodated her wish for a light crispbread by inventing Melba Toast, created Pêche Melba, which insulated scoops of vanilla ice cream in a pink-tinted syrup that made them resemble peaches. Less warmly remembered is the Marlene, a concoction of blue ice cream inspired by Marlene Dietrich’s most famous film The Blue Angel. During her 1968 Australian tour, the chef at a Sydney hotel chose to unveil his creation at a press conference. Marlene placed it on the floor by her chair where it melted, unsampled. It has not been heard of since.

Military men and their victories are frequently celebrated in food. When Marshal Ferdinand Foch, Supreme Commander of French forces during World War I, visited New Orleans in 1919, the city’s foremost restaurant, Antoine’s, created Oysters Foch. As damaging to the digestion as any bayonet, it consisted of oysters breaded with cornmeal, deep-fried, served on toast smeared with foie gras, the entire dish doused in the buttery, tarragon-flavored Sauce Colbert. Three decades later, when the grandiose Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery announced that he preferred to go into battle only when his troops outnumbered the enemy 17 to one, Ernest Hemingway persuaded Paris’s Ritz Hotel bar to serve the no-less-disastrous Montgomery Martini, made with one part of vermouth to 17 of gin.

Among dishes created for military celebrities, few compare with that named for André Malraux. Novelist, filmmaker, convicted plunderer of Cambodian tombs, he became a leader of the resistance during World War II. Not one to let the Germans interfere with his social life nor his pursuit of pleasure, he regularly visited Nazi-occupied Paris to dine with his mistress, the writer Louise de Vilmorin, at Fouquet’s on the Champs-Élysees, or at Lasserre, where proprietor René Lasserre prepared his favorite dish: a whole pigeon, deboned, stuffed with foie gras and wild mushrooms, briefly roasted with vin jaune and truffle juice, and served with baby onions, carrots, beets, turnips and pear on a bed of lettuce, dressed with a reduction of the cooking juices mixed with Madeira. The fame of this dish spread as far as Washington, D.C. After dining with Richard Nixon at the White House in 1972, Malraux told Lasserre, “Consider yourself flattered, my friend. As we began dinner, Nixon smiled and said, ‘Monsieur le Ministre, I don’t claim our kitchen is the equal of Lasserre but we will do our best.’”

After the war, Malraux locked horns with another alpha male, Ernest Hemingway. Visiting the writer in his suite at the Ritz, where he was holding court after a lightning dash from the Channel coast just after D-Day, Malraux asked how many men he had commanded in the field. When Hemingway ducked the question—the Geneva Convention forbade war correspondents taking part in hostilities—Malraux informed him he had led a brigade, then demanded how many men Hemingway had actually killed. At this, one of the guerrillas of his retinue drew him aside. “Listen, Papa,” he whispered, “do you want me to shoot this asshole?” Fortunately, Malraux was spared to become Minister of Culture under General de Gaulle.