“After the first glass of absinthe,” wrote Oscar Wilde, “you see things as you wish they were. After the second, you see them as they are not. Finally you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world.”

As Orson Welles remarked in the film The Third Man, Switzerland’s contributions to European culture begin and end with the cuckoo clock. Absinthe is a partial exception. The 18th-century Swiss distillers who flavored alcohol with anise, fennel and the bitter herb Artemisia absinthium—wormwood—may not have expected this pale green brew with the taste of licorice to appeal so powerfully to their French neighbors. They would, however, have known that pastilles of salted licorice—réglisse—were a popular French aid to digestion: something Anglo-Saxons found difficult to believe, raised as they were on licorice as confectionery: slick black straps of the stuff, called Liquorice Whips, or gaudily tinted cubical sweets known as Liquorice All-Sorts.

Unlike the candy, absinthe was not for children. With an alcohol level approximately double that of whiskey, the “hard stuff” didn’t come much harder. Even the traditional method of imbibing absinthe, trickling ice water through a cube of sugar into the spirit, didn’t dilute it much, since serious drinkers stopped the moment its color changed to a cloudy beige. Others drank it neat, relishing the translucent pale green that earned it the name La Fée Verte (The Green Fairy).

Through the late 19th century and into the early part of the 20th, absinthe was the preferred tipple of bohemian France. Drunk in moderation, it was no more dangerous than whiskey or brandy, unless, as was occasionally the case, a careless distiller failed to extract all the thujone, the alkaloid that gave it that special kick—at the cost, however, of one’s health. Even as he refilled his glass, the poet Paul Verlaine, an absinthe addict, cursed “this horrible drink, the source of folly and crime, of idiocy and shame, which governments should tax heavily if they do not suppress it altogether.”

The risks didn’t deter Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Edgar Degas, Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, Vincent van Gogh, Marcel Proust and Erik Satie, all of whom indulged. Charles Baudelaire included it among the “artificial paradises” of his poem cycle Les Fleurs du mal (Flowers of Evil). Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who often carried a supply in the glass tube hidden in his cane, drank it in a potent cocktail called Tremblement de terre (Earthquake), which mixed absinthe with cognac, to devastating effect. (The same ingredients, with the addition of a cube of sugar and a dash of bitters, make up the Sazerac, most associated with the city of New Orleans.)

L’Absinthe, Edgar Degas, 1875–76, Musée d’Orsay

The Green Muse, Albert Maignan, 1895, Musée de Picardie d’Amiens

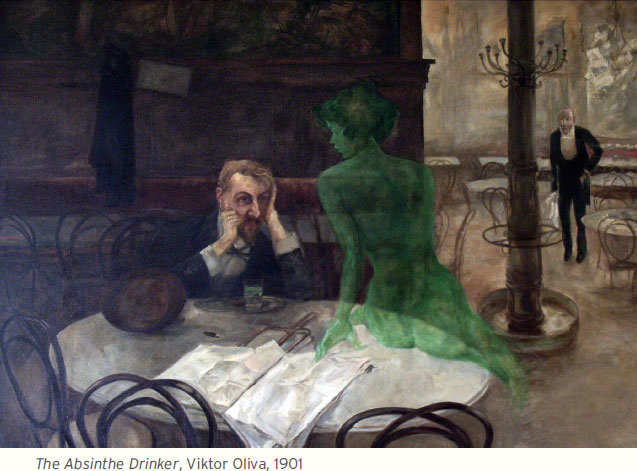

Many painters, including Picasso, Manet and Toulouse-Lautrec, documented the effects of inferior absinthe or excessive imbibing. Like Edgar Degas’ Absinthe, a painting of a couple sitting numbed in a café, they often captured the affectless daze and general untidiness associated with addiction. (Even so, Degas later admitted, to his embarrassment, that, unable to find two suitably degraded addicts, he hired actors to pose.) Lesser artists were not so apologetic about surrendering to melodrama. In Albert Maignan’s 1895 The Green Muse, a poet is lured from his desk by the fairy herself, who places her hands over his eyes, filling his mind with thoughts of the nearest bar. Viktor Oliva’s 1901 The Absinthe Drinker shows the fairy, naked, perched on the restaurant table of an inebriated gentleman while a waiter hovers in the distance, wondering why his client is acting so strangely.

In 1914, alarmed by the national rise in alcoholism, the French government banned absinthe on the pretext that it sapped the will of young men of military age, making them disinclined to leave the trenches and walk into the fire of German machine guns. (Conveniently forgotten was the fact that the army had once issued absinthe to troops as a possible protection from malaria.) Stigmatized as the bad boy of booze, absinthe was attacked by journalists in tirades that verged on the hysterical. “Absinthe makes you crazy and criminal,” claimed one wildly inaccurate report, “provokes epilepsy and tuberculosis, and has killed thousands of French people. It makes a ferocious beast of man, a martyr of woman, and a degenerate of the infant, disorganizes and ruins the family and menaces the future of the country.”

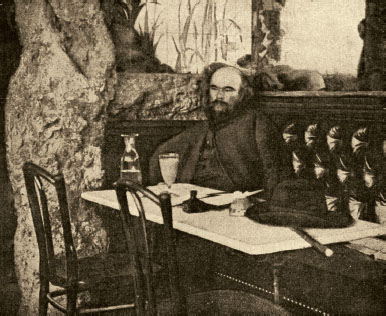

Paul Verlaine, portrait in front of a glass of absinthe at the Café Procope, Paris

For half a century, absinthe hovered in a limbo of fantasy and speculation. Distillers ceased production. Stocks in hotels and restaurant cellars dwindled until only a few authentic pre-1914 bottles survived. Enthusiasts made do with Pastis and Pernod, flavored with licorice and anise. After World War II, researchers used the few bottles unearthed from forgotten caves to analyze the content and recreate the formula, and the green fairy once again floated above the cafés and bars of Paris. The stigma remained, however. A 1970 exhibition in the Jeu de Paume hung Degas’s painting next to a photograph of a numbed Paul Verlaine seated with a glass of absinthe before him.