Preferring to work en plein air, many 19th-century artists moved to the country. The greater the distance from the city, the cheaper it became to buy property and staff it. In 1907, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, crippled with arthritis, bought Les Collettes, a farm at Cagnes-sur-Mer, in the hills above Nice, and had the farmhouse rebuilt to accommodate his problems with movement. As well as a car and chauffeur, he installed an equally rare private phone. A team of servant girls, directed by his wife and former model, Aline, catered to his every wish, preparing his favorite meals, physically carrying him to a scenic location, then disrobing to pose for him.

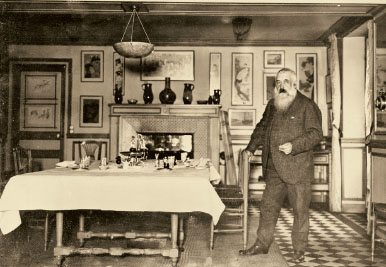

Monet in his dining room decorated with his collection of Japanese wood-block prints

At Giverny, 80 kilometers from Paris, Claude Monet established one of the most enduring of artists’ environments. After moving there in 1883, he bought the property in 1890, along with a small working farm, and extended it to accommodate his 10-person family. While meticulously planted flower beds demonstrated his theories about color, a Japanese-style garden inspired his studies of nymphéas or water lilies that preoccupied him until his death in 1926.

In addition to Marguerite, his cook, Monet employed a gardener, Felix, and a chauffeur/sommelier who drove him as well as managing the wine cellar and maintaining his studio. Additional staff worked the farm, rearing poultry for the table and harvesting the eggs that enriched the Monet diet. Boxes in the kitchen large enough to hold 116 eggs were kept permanently filled.

Monet’s day began about 5 a.m., when he breakfasted on cheese, an omelet aux fines herbes, sometimes with the addition of cold meat or sausage, accompanied by toast and confiture, washed down with tea. With Alice, his wife, he discussed the week’s menus, based on seasonal produce. Salads and vegetables came from their own potager or vegetable garden. Wild cèpes and girolle mushrooms, asparagus, fresh herbs and greens such as roquette would be foraged from the fields and verges around Giverny.

Monet never entertained at night, going to bed at 9:30, but frequently invited friends to Sunday lunch, which began promptly at 11:30 a.m. In summer, they ate alfresco. Even before he moved to Giverny, Monet celebrated the pleasure of open-air eating in the 1873 painting Le Déjeuner (Lunch), an idyllic image of ladies about to sit down at a table set out in shade, with fruit and wine.

In colder weather, they ate in the lemon yellow dining room, its walls hung with some of Monet’s collection of Japanese wood-block prints. Monet himself designed the dinner service of a yellow and blue Limoges porcelain, edged in a thick stripe of yellow bordered by a thin line of blue, a pattern that became nationally popular. Guests might include poets Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Valéry, sculptor Auguste Rodin, painters Paul Cézanne, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and James McNeill Whistler.

Monet’s dining room at Giverny

The Galette, Claude Monet, 1882

A typical meal began with tomatoes or onions stuffed with a minced meat farce, or mushrooms baked with butter under a gratin of breadcrumbs. A gigot of lamb or a roasted chicken followed. In honor of his adoptive Normandy home, Monet often served cider rather than wine. Though he didn’t cook himself—“I have two skills only,” he wrote, “horticulture and painting”—the artist, a serious gastronome, kept a diary detailing meals he had enjoyed in his travels. Marguerite attempted to replicate some of them in her blue-tiled kitchen, with varying success. After sampling Yorkshire pudding at the Savoy hotel in London, Monet obtained its recipe for this savory baked batter cake, traditionally served with roast beef, but it never tasted quite the same in France. Marguerite had more success with banana ice cream, which became a regular feature at Monet’s table.

Concerned that France’s culinary heritage was being eroded, Monet collected recipes for classic dishes. Cézanne, a native of Provence, supplied details of the Mediterranean seafood stew bouillabaisse, while Jean-François Millet, painter of The Gleaners and other images of the harvest, explained how to make bread rolls. Monet particularly enjoyed the upside-down apple dessert tarte Tatin, invented in 1880 by two sisters, Stéphanie and Caroline Tatin. Lacking an oven, they cooked an apple cake on the stove-top, where the heat reacted with butter and sugar to caramelize the fruit. Determined to have the authentic recipe, Monet traveled to the Tatins’ home in Lamotte-Beuvron, 160 kilometers south of Paris, to acquire it.