Attempting to review The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, a fanciful autobiography of the Spanish Surrealist, American humorist James Thurber was forced to concede defeat. “Let me be the first to admit,” he wrote, “that the naked truth about me is to the naked truth about Salvador Dalí as an old ukulele in the attic is to a piano in a tree, and I mean a piano with breasts.”

Never one to skimp on exaggeration, Dalí claimed mastery not only of the studio and bedroom but of the kitchen as well. He claimed to have begun cooking at the age of 6, though it’s debatable whether or not his recipes were edible. In cooking meat, he advised retaining the bones, and, in the case of lobster, shrimp or snails, the shells also. “The most philosophical organs man possesses,” he wrote, “are his jaws. It is at the supreme moment of reaching the marrow of anything that you discover the very taste of truth.”

Food lies at the heart of many Dalí paintings. He first sensed intimations of its future importance in 1931, at the conclusion of a Parisian dinner party. Too tired to accompany his wife, Gala, and her friends to a late-night cabaret, he remained at the table, surrounded by the debris of supper. His thoughts returned to the half-completed canvas in his studio. He’d hoped to reflect on the imprecision of memory and our tendency to distort, if not delete entirely, that which we find unpalatable, but for the moment he’d reached an impasse.

He had already painted the background, a neutral landscape, flat as a table, interrupted only by a distant headland and some enigmatic slabs, one of them topped by the gaunt branches of a dead tree. In the foreground lay a mysterious figure, its only recognizably human feature a single large eye, closed in sleep.

Some element was needed to bind all these elements into a coherent whole; a metaphor to suggest our shifting, elastic, melting perception of reality. At that moment, Dalí’s eyes fell on a half-eaten Camembert cheese among the remains of the meal. Deliquescent at room temperature, the interior had oozed out onto the wooden table, the surface of the drying cheese as glossy as porcelain.

The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dalí, 1931, Museum of Modern Art

Seized with inspiration, Dalí hurried to his studio. Snatching up his palette, he smeared together white and yellow pigments and began furiously to paint. By the time Gala returned, he had enhanced the landscape with three clock faces, draped, limp as fried eggs, over a branch of his dead tree, the edge of one featureless slab, and, saddle-like, over the sleeping foreground figure. Large as plates and droopy as gloves, these “soft watches” would appear in his work for the next 30 years, a metaphor as distinctive as it was enigmatic.

With this painting, The Persistence of Memory, Dalí had arrived, and his emblem under which he would conquer the art world was food. Alert now to the power of culinary metaphors, he added eggs to his artistic larder. In every size from the minuscule to the gargantuan, sometimes fried, more often raw, they populate his work. One scholarly analysis suggests they represent “the Christian symbol of the resurrection of Christ, but also act as an emblem of purity and perfection, as well as evoking concepts of uterine memory and rebirth”—not inappropriate for an artist who insisted he could remember every detail of his life, right back to the womb.

Dalí had a special affection for the oursin or sea urchin. Not only did the brittle shell and ovoid shape resemble those of an egg; its pink, slightly scented roe was itself made up of countless tiny eggs. As early as 1929, his film Un chien andalou, made in collaboration with Luis Buñuel, dissolves from a woman’s hairy armpit to a sea urchin’s black-spined shell. True to this sexual subtext, Dalí, rather than eating the oursin in the customary manner, scraping the raw roe from its shell, preferred it mixed with chocolate, supposedly a traditional Catalan aphrodisiac.

During his first days as a member of the Surrealists, experimenting with juxtaposing unrelated objects to create a fresh and unexpected reality, Dalí filled the pockets of a dinner jacket with small glasses of milk, an object he called Le Veston aphrodisiaque (The Aphrodisiac Dinner Jacket). Previewing the work to the assembled brotherhood at one of its nightly séances, he was attacked by André Breton’s lieutenant Louis Aragon, then a strict Stalinist, on the grounds that it wasted milk while women and children in Paris were starving. When the piece went on show in a gallery, Dalí replaced the milk with crème de menthe, only to find that his helper, directed to keep the glasses filled as the liqueur evaporated, was actually drinking it. This practice halted abruptly when Dalí replaced crème de menthe with green ink.

The love of Dalí’s life was his partner and eventual wife, Gala. Formerly married to Surrealist poet Paul Éluard, she was 10 years older than Dalí, and much more sexually sophisticated, having shared a ménage à trois with Éluard and painter Max Ernst. Primarily a voyeur, Dalí derived most satisfaction from watching the sexual activities of others, including Gala. He took a similarly detached view of food, preferring to write about and paint it rather than eat it. These preoccupations converged when he used Gala as a model. At various times, he painted her with a loaf of bread balanced on her head, and with two lamb chops on her shoulder.

In 1937, asked to propose film ideas for the Marx Brothers, Dalí had suggested a banquet at which guests sat not at a long table but occupied an enormous bed. In September 1941, stranded in California by the war, he drew on the same idea for a dinner and costume ball at the Del Monte Hotel in Pebble Beach. The theme was Night in a Surrealist Forest, and guests were asked to dress so as to recall their worst nightmare. Supposedly a fund-raiser for artists in exile, the event attracted such celebrities as Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, Jack Benny and Ginger Rogers. As Gala, her costume topped by a unicorn headdress, reclined on a red velvet bed, guests were served the fish course in a high-heeled shoe. Lifting the metal cover of the second course, they found live frogs.

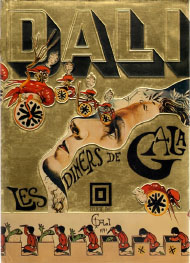

In 1973, a lavish cookbook, Les Dîners de Gala, appeared under Dalí’s name. “Don’t look for dietetic formulas here,” warned the introduction. “If you are a disciple of one of those calorie-counters who turn the joys of eating into a form of punishment, close this book at once; it is too lively, too aggressive, and far too impertinent for you.” Recipes, each illustrated with a Dalí painting, were arranged under such headings as “Sodomized Entrées.” They included Thousand Year Old Eggs, Roast Peacock, Frog Pasties, and Veal Cutlets stuffed with Snails. The chapter devoted to aphrodisiacs included recipes for a Casanova Cocktail and Stewed Beef Eros.

Les Dîners de Gala was the brainchild of Dalí’s secretary and business manager, Captain Peter Moore. Aside from the illustrations, the artist had little to do with it, nor were its recipes intended to be practical. Despite claims of precocious culinary talent, Dalí was no cook, preferring to dine on room service delivered to his suite at Paris’s luxurious Hotel Meurice. Favorite venues in New York included the Russian Tea Room, one of whose waiters he recruited to model for his painting Christopher Columbus, and the King Cole Lounge of the St. Regis Hotel, where the anal Dalí particularly enjoyed its Maxfield Parrish mural showing the reaction among King Cole’s courtiers as his majesty expels a fart. When he did visit a restaurant, invariably without making a reservation, he took the best table, ordered a lavish meal for his retinue, then departed with a lordly order to send the bill to his hotel, where it was ignored.