Sean Kinsella, chef and owner during the 1970s and ’80s of Dublin’s most distinguished restaurant, the Mirabeau, made only minimal concessions to the eating public. His establishment on a quiet side street in Sandycove barely advertised its existence. Instead, one looked for his Rolls-Royce parked outside. The menu had no prices. If you had to ask, you couldn’t afford them.

Waiting for their table, patrons relaxed in a lounge over a glass of wine. Periodically, waiters circled the room with salvers on which rested a leg of lamb, a fillet of venison, a whole salmon.

“The côte de boeuf,” they murmured, pausing before each party. “The trout.”

One well-lubricated client couldn’t resist a joke. As the next waiter departed, he said loudly after him, “If none of you want it, I’ll have it.”

Nobody laughed. Facetiousness was as misplaced here as in St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Dinner passed well enough until the bill arrived. After a quick addition, the jokester called back the waiter.

“Look here, pal,” he said. “Your sums don’t add up. You’ve overcharged me a fiver.”

With a startled look, the man disappeared, but returned shortly after, followed by Kinsella himself, still wearing his chef’s tablier and toque.

Snatching the bill, he did a quick calculation.

“You are correct, sir,” he said. “Our calculations were in error.”

Crumpling the bill with one hand, he dropped it to the floor. “… and accordingly there will be no charge for your meal tonight …”

Before the man could stammer his thanks, Kinsella leaned forward until his face was only a few centimeters from that of the customer.

“… but,” he growled, “I never want to see you in my restaurant again.”

Although the celebrity chef and his accompanying myths often appear a 21st-century creation, born of the shotgun marriage between reality TV and the restaurant culture, their roots lie more than two centuries back, at the moment when revolution, in destroying France’s great houses, threw their most gifted servants onto the open market. Some remained in France and opened restaurants. Others went to the few surviving great houses, often outside France. Carême cooked for Britain’s Prince Regent at the Brighton Pavilion and for Czar Alexander I of Russia at the Winter Palace. Georges-Auguste Escoffier, in partnership with César Ritz, managed London’s Savoy Hotel and, later, Paris’s Ritz.

These culinary hired guns were the first food professionals to recognize that image counted as much as expertise. Even more than today’s Gordon Ramsay, Jamie Oliver and Wolfgang Puck, they were showmen, ready to demonstrate their expertise for all who could meet their price. For Nellie Melba, Escoffier created Melba Toast and Pêche Melba. He also arranged a banquet in which the initial letters of the dishes spelled out the hostess’s name, and another for a gambling syndicate that won a fortune betting Red Nine. All the food was red and the number nine dominated the menu. Anyone arranging a dinner did so in collaboration with the chef de cuisine, who advised not only on which ingredients were at their best, but ensured that sworn enemies were not seated next to one another, nor mistresses next to wives.

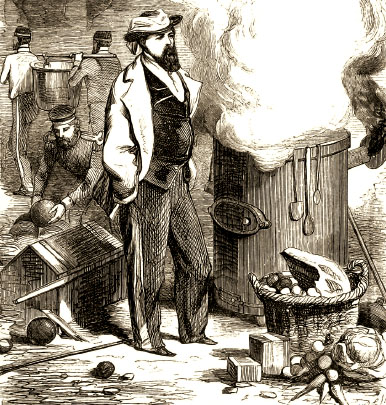

Alexis Soyer demonstrates his stove during the Crimean War

No 19th-century chef was more flamboyant than Alexis Soyer. Fleeing an increasingly unstable continental Europe, he took over the kitchens of London’s Reform Club in 1837, installing gas ovens and refrigeration. While Carême shared the sartorial sense of his masters and personally designed the white cotton toque and apron now the chef’s standard uniform, Soyer’s clothes reflected his eccentricity. According to one description:

He wore a kind of paletôt [double breasted jacket] of light camlet cloth, with voluminous lapels and deep cuffs of lavender watered silk; very baggy trousers, with lavender stripes down the seams; very shiny boots and quite as glossy a hat; his attire being completed by tightly-fitting gloves, of the hue known in Paris as beurre frais (fresh butter)—that is to say, light yellow. Every article of his attire was cut on what dressmakers call a “bias,” or as he used to designate it ‘à la zougzoug’ [zig-zag]. He [had] an unconquerable aversion from any garment which exhibited either horizontal or perpendicular lines. His very visiting-cards, his cigar-case, and the handle of his cane took slightly oblique inclinations.

Exceptionally for the self-interested culture of the kitchen, Soyer had an active social conscience. Having visited the Crimea and seen troops cooking their meals over tiny open fires, always at risk from snipers, he designed a field stove that burned almost any fuel but never showed a light. It was still in use in the 1980s. He also reorganized the provisioning of army hospitals, and trained and installed in every regiment a “Regimental cook,” eventually to evolve into the Army Catering Corps.

Less successfully, he also intervened to alleviate the 1847 famine in Ireland following the failure of the potato crop. As well as contributing money from the income from his books, he created an economical Famine Soup that used a minimum of meat, eked out with the leaves and trimmings of vegetables that most chefs consigned to the garbage. Stung by critics who charged that a bouillon of 12 pounds of beef to 100 gallons of water was barely soup at all, Soyer traveled to Dublin and set up a soup kitchen that fed tens of thousands who would otherwise have starved. William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1849 novel The History of Pendennis included a character named “Alcide Mirobolant,” widely recognised as a parody of Soyer. (“Mirobolant” is French for “fabulous” or “astonishing.”)

Soyer’s philanthropy contrasts with the underhanded behavior of the dignified and superficially respectable Escoffier. While managing the Savoy, he and Ritz skimmed a fortune in kickbacks from food and wine suppliers. Waiters were urged to push champagne, since wine merchants paid a bonus on every cork returned. Escoffier even set up a fake company to sell food to the hotel at inflated prices and an agency for kitchen staff that charged the Savoy for hiring his own appointees. On March 8, 1898, Escoffier, Ritz and their entire kitchen staff were dismissed for “gross negligence and breaches of duty and mismanagement.” A newspaper reported, “Sixteen fiery French and Swiss cooks (some of them took their long knives and placed themselves in a position of defiance) have been bundled out by the aid of a strong force of Metropolitan police.” With Escoffier, Ritz moved to Paris and took over the hotel bearing his name, the cellars and kitchens of which were already filled with supplies paid for by the Savoy.

Had television existed in Victorian times, Soyer’s instant stardom would have been assured. Pioneered by Julia Child, the cookery show proved the most durable and economical of all programs, requiring only a simple set and a performer with the personality, as dictated by the first rule of marketing, to “sell the sizzle, not the steak.” Few viewers ever tried the dishes demonstrated. As in pornography, watching the process was enough.

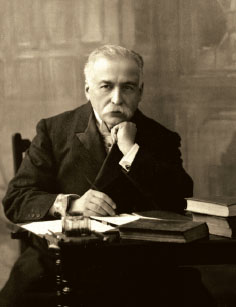

Young Cook in the Kitchen, Joseph Bail, 1893

The “secret sauce” of the cookery show was alcohol. Ever since The Galloping Gourmet, Graham Kerr, pioneered the practice of cooking with a glass of wine in hand and insisted that most dishes benefited from “a short slope of sherry,” alcohol was a constant of TV cookery, contributing to the flair that characterized the best performers. The 1950s demonstrations by British chef Fanny Cradock were sufficiently popular to fill the 5,000 seats of London’s Royal Albert Hall, notwithstanding husband Johnny’s obvious inebriation. A bottle or two of wine also accounted for the on-air ebullience of Floyd on Food’s Keith Floyd, as well as his convictions for driving under the influence.

Among the canvases of those 19th-century painters who took cooks as their subjects, alcohol is also omnipresent. The numerous images of young cooks by Joseph Bail and Théodule Ribot, working in the documentary style of Chardin, include one of a pot boy sneaking a bottle of wine. William Orpen’s 1921 Le Chef de l’Hôtel Chatham, proud of the beard he’s permitted to grow as a badge of his importance, stands with hands on hips, toque and tablier worn with all the confidence of a military officer—and, inevitably, a bottle of wine and half-filled glass at his elbow.