Chapter Seven

Fast Slovaks on the Steppes

Prior to his seizure of the Czech lands Hitler’s plans centred on fracturing the Czechoslovakian state. After the Munich Agreement the Czechoslovak government under President Hacha granted autonomy to Slovakia, but it received intelligence on 9 March 1939 that Slovak separatists were plotting to overthrow the republic. The Slovak Prime Minister Dr Tiso was dismissed but promptly flew to Berlin to see Hitler on 13 March.The following day, having reached an agreement with Hitler he returned to Slovakia and declared independence, rupturing the union between the two peoples.

Hitler’s troops occupied Moravska-Ostrava, one of the Czechs’ key industrial towns and were poised along the border of Bohemia and Moravia.The beleaguered Hacha turned to Hitler who announced he would take the Czech people under the protection of the German Reich. Hacha informed his Cabinet they must surrender and the German Army rolled in.

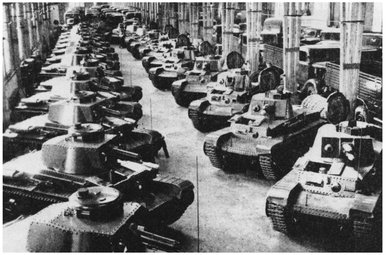

Unlike the Czechs, the Slovaks were permitted to retain a standing army; however, most of the equipment held by the Czechoslovakian Army was seized by Hitler and passed on to the German Army and his other Eastern Front allies. Although Czechoslovakia was a major tank manufacturer and Bohemia and Moravia would continue to churn out tanks for Hitler, the Slovak Army received very few LT-35s and LT-38s as a result of the carve-up. This almost complete lack of tanks and indeed motor transport was to greatly hamper the Slovaks’ contribution to Hitler’s war effort. Although they may have been willing, like many of the other allies they simply lacked the tools of mechanised warfare.

Premier Tiso’s rump Slovak State provided Army Group South with a Slovak Army Group of two infantry divisions. Initially the Slovaks launched 45,000 men into the Soviet Union just four days after the German invasion. However, their lack of transport soon meant that they were lagging behind the sweeping advance so it was decided to create a mobile unit for deployment in the Ukraine.

This was done by cobbling together all the motorised units into the grandly-sounding Slovak Mobile Command–this was better known as Brigade Pilfousek after its commander General Rudolf Pilfousek. It consisted of the 1st Tank Battalion with just two tank companies, two companies of anti-tank guns and two supporting companies of motorised infantry. The remaining forces were assigned to security duties way behind German lines.

The brigade was sent through Lvov and on toward Vinnitsa. Lacking the ability to control it in the field, the unit fell under the tactical command of the German 17th Army. Fighting against the Red Army the brigade drove through Berdichev, Zhitomir and towards the Ukrainian capital Kiev. In August 1941 the largely ineffectual Slovak Army Group was withdrawn and the best units reorganised into the 10,000-strong 1st Slovak (Mobile) Infantry Division and the 6,000-strong 2nd Slovak (Security) Infantry Division. An offer to send a third division in order to create a full Slovak Corps was rejected by the Germans in 1942.

The Mobile Division under General Gustav Malar was also known as the Slovak Fast Division. This was somewhat optimistic in light of the quality of its motor transport and paucity of tanks. In effect it was little better than a rudimentary motorised infantry division. By September this unit was back at the front fighting the Soviets near Kiev. It was then sent as a reserve to Army Group South and fought along the Dnieper. By early October the Fast Division was fighting as part of the 1st Panzer Army on the far bank of the Dnieper. It then spent the winter holding positions along the Mius River.

The following year the Slovaks advanced into the Caucasus and took part in the attack on and capture of Rostov. In the summer of 1942 JozefTuranec took command of the division and led it across the Kuban. Later in the year it was reinforced by the 31st Artillery Regiment redeployed from the 2nd Slovak (Security) Infantry Division. In the New Year Turanec was replaced as commander by Lieutenant-General Jurech.

Following the Axis forces’ shattering defeat at Stalingrad in the winter of 1942/43 the German position in the Caucasus became untenable and they withdrew to avoid entrapment. The Fast Division was almost caught near Saratowskaya but managed to get away. While the survivors were airlifted out of the Kuban to the Crimea, they had little choice but to abandon all their heavy equipment and remaining vehicles. The Slovaks then fought to cover the withdrawal over the Sivash and Perkop land bridges.

General Elmir Lendvay was then appointed to command and the division was pulled out of the line for a refit before going back into battle near Melitopol. When the Red Army broke through German lines the Slovaks were scattered and 2,000 men captured. This pretty much ended Slovakia’s support for Hitler on the Eastern Front.

In 1944 the Fast Division was reconstituted with some infantry companies, flak companies, 150mm howitzers and 37mm anti-tank guns. Barely 800-strong this was called the Tartarko Combat Group and was sent to the Crimea. That summer with trouble brewing in Slovakia itself the division was pulled from the line and disarmed and used as a construction brigade in Romania. The 2nd Slovak Division was sent on rear-area anti-partisan and security operations until desertion rates resulted in it being converted into a construction brigade in late 1943 and sent to Italy. Although the Slovaks had shown great courage on the Eastern Front, ultimately there was only so much they could achieve in light of their limited resources.

In the wake of the partition of Czechoslovakia, Slovak Prime Minister Dr Tiso seen here on the right with Hitler declared Slovakia independent and committed 45,000 men to Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union.

In the late 1930s Czechoslovakia had a modern army numbering 800,000 men backed by defence industries that were the envy of Europe. Crucially, the lack of political will to stand up to Hitler over the Sudetenland meant the loss of its industries, the occupation of Prague and the destruction of the entire country.

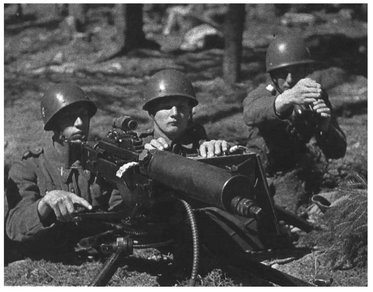

The Slovaks were able to provide the German Army Group South with a Slovak Army Corps of two infantry divisions. Their lack of motor transport led to the creation of Brigade Pilfousek, which comprised motorised infantry, anti-tank guns and the 1st Tank Battalion.

Slovakia lost out in the tank stakes as the factories for the LT-35 seen here and the LT-38 were in the Czech lands.

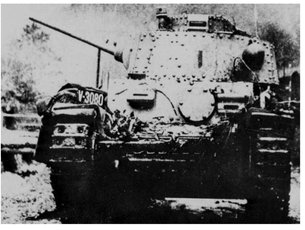

The Slovaks were reliant on ex-Czech LT-38 light tanks supplied by the Germans. About forty served with the 1st Slovak (Mobile) Division in Russia.

The Slovak Army also ended up with a number of LT-35s as it inherited Czechoslovakian equipment stored within its borders.These were also deployed with the mobile brigade and the mobile division, though the latter was little more than a rudimentary motorised infantry division.

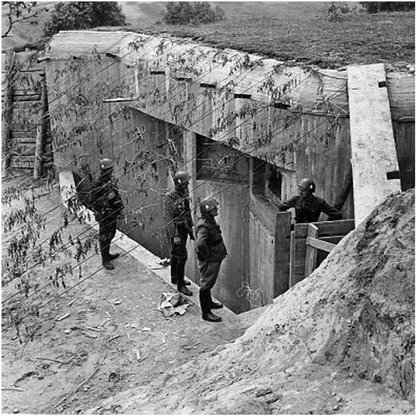

Slovak soldiers examine Russian fortifications following the invasion of Russia.

Slovak infantry on parade. The Slovak armed forces were predominantly an infantry army and this greatly limited the contribution they could make to the German war effort.

These Slovak LT-38s were soon overwhelmed by the Russian winter and most of them were lost in the Kuban when the Mobile Division was airlifted out. Unlike his other allies, Hitler supplied the Slovaks with very few tanks.

The Slovak Army could just about cope with the Soviet T-26 light tanks but anything else greatly strained their meagre anti-tank resources.

After the Axis defeat at Stalingrad the Slovak Fast Division had to abandon all its heavy equipment in the Kuban, which included any remaining LT-38s.

Infantry from the Slovak Fast Division posing for the camera.

Slovak troops receiving gallantry awards. Though brave fighters their lack of tanks, motor vehicles and adequate anti-tank guns cost them dearly. When the Fast Division collapsed 2,000 men were captured by the Red Army. These men are probably government loyalists following the Slovak rising.

Members of the Czechoslovak Army during the Slovak national rising against the Nazis in 1944. This was swiftly crushed and Slovakia remained under German control until the very end.

Slovak gunners laying down fire on the advancing Red Army.