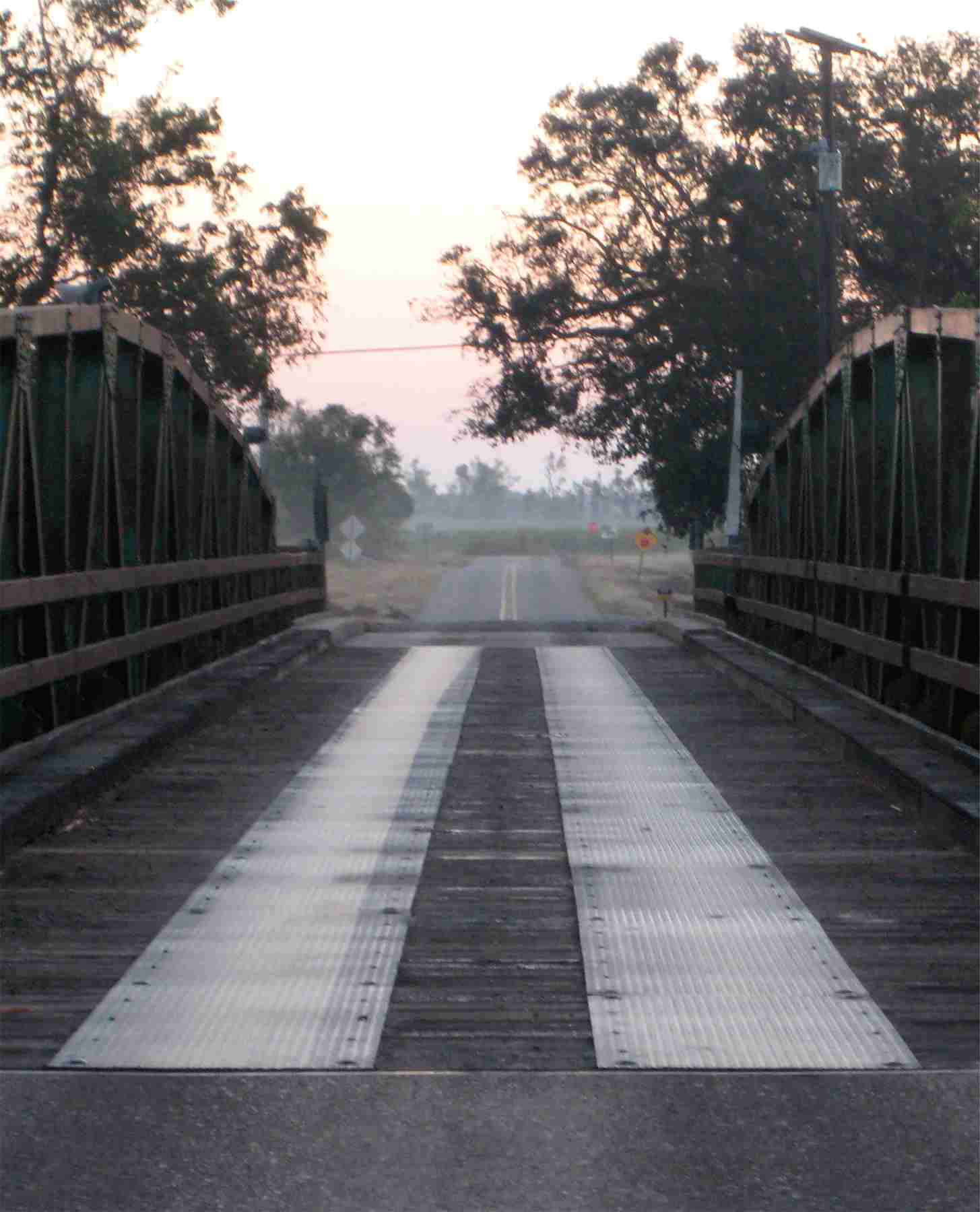

Photo credit: Natalie Baszile

2.

Everyone Beneath Their Own Vine and Fig Tree: A Remembering in Seven Parts

GENESIS

This is a remembering.

On the land, we wrote in seed a coded language centered in the archive of hidden knowledge planted in the soul of each and every African who managed to arrive alive on these shores. On earth, in water, and in sky, we passed from one generational era to the next an incredible lore, ancient yet new. We knew which trees were elevators of spirit, which soil enriched our blood, what water stood between us and the dead, and which constellations had the power to emancipate. The music of the Universe and the dance steps it dictates were birthrights, not mysteries. We were forced . . . coerced into not only raising a nation from its infancy, but walking the Atlantic world into modernity, leaving behind what blood we hoped we would not miss.

EXODUS

This is a remembering.

One day there will be no one who remembers or who lived the life of those who left bondage and went into freedom with a dream and a plow. There will be a permanent amnesia.

Before freedom came, some of us ran away to survive. We dreamed of a boat ride back to Guinea, a red carpet to respond to the red flag that brought us. Some made it. Some went north to Canada and put tobacco in the ground, just out of reach of a killing frost. Some went south and east to the islands and cast a net, others went southwest and herded cattle with hides as varied as blossoms and fingerprints. Many, without choice, stayed through the worst years of “the slavery.”

The nightmare ended in a hail of blood. The day of Jubilee arrived in five acts: 1862 to 1863 to 1864 to the Surrender to Juneteenth; the day of liberation did come, winding its way from autumn to summer. Chains rusted and broke.

The people I celebrate who occupied the land between slavery and civil rights splashed on Florida water cologne and crushed dark bricks for blush because no makeup existed for them. They chose their children’s names by Bible prophecy or by season or day of the week. Planting and harvest were the birth rhythms. They resisted white supremacy by making irresistible music genres and food and words and dances. Their doors were painted “haint blue” to keep the evil off.

Their grandparents were the Antebellums. They had hog bladders for firecrackers. Names were based on whispers from Africa. Jesus wasn’t official, and spirits in the trees weren’t obsolete. Cotton, tobacco, rice, and sugar defined life but not for their own sake. They fought and prayed in ways too subtle for us to appreciate. They paid an enormous price for our freedom.

Their great-grandparents were the African exiles. They were America before America. They brought the light of the supposed “Dark Continent.” They seeded a civilization with other untouchables. They left treasure maps in words, ingredients, DNA, names, and talk of pots silencing laughs.

Their great-grandparents were the last generation to be untouched. They only knew gods that looked like their reflection in the streams. They dreamed their children into the cosmos. They understood the language of the dwarves in the rainforest. They did not fear death. They were free.

No book or page will do the trick. All the voices will be gone. We will lose more than we know. We will lose the knowledge of who was where, what seeds they planted, what animals they raised, how they made a life from no life, how they made a set of rules meant to kill them into seeds of change, how they made bricks, how they made mortar, how they made churches and praise houses and big houses and outhouses and grape arbors, peach orchards, wells and dipper gourds, tobacco barns and headstones and porches and swings and life from no life.

Like the generations before them who knew different fates, a book will be closed on a certain people. They were an agrarian people who marched out of slavery and into semi-freedom. These were the children of Jim Crow’s time, a people who built their lives out of the red clay dust and muck of loam and gritty sand. They are dwindling, and we, those who remember the shadows of their ways, are dwindling. We scramble to remember faces in early photographs; we go to courthouses to see which graves are under which mall or gated development or gas station. We work because we know the night is coming and someone needs to have a light. This is a remembering. Now is the time to remember.

We have already begun to forget. The plows are gone. The millions of acres have shrunk. We wax nostalgic about “they.” “They used to.” “They,” never “we.”

SOIL

Take your finger, place it on the Mason-Dixon line, and start to trace your way back. Let your digits get wet in the brackish tides of Chesapeake Bay, go to the appendages of land sticking out into the water, the place where it all began, all of this inherited strife. Go against the Piedmont spine, feel the tops of the pines and oaks, dip down to the clay, and soil your fingers with the iron within. Move down the coastal line, and mash yourself into the sand. Dance over to the loam, the Black Belt, the long rich belt where once an ancient sea stood and Yemonja swayed while her lullabies became fish. Push toward the Mississippi out against more mountains down to the bayous and melting coastline. This borrowed place, now partly made of your ancestors, is your old country.

Some of us were sharecroppers, others tenants, but many were landowners. Everyone saw themselves as living a verse of Bible, beneath their vine or fig tree. Here we waited for the good times, prayed against the inevitable bad. On mattresses of corn husks or Spanish moss we planted the next generation. In the bottoms we planted sweet potatoes and melons; but where the land would not yield, we planted the bodies that became the ancestors.

ROOTS

Before Georgia, there was Guinea. There were dawns that went back to the very beginning of time. Just before our leaving, the dawns were the same as they were after we left. Two hours before light, came the first crowing. Then came the barking of dogs and prayers carried up in circles and the sparking of fires and the sound of the mortar and pestle giving the day its heartbeat.

When we danced, we moved according to the tasks of the field and farm. We began to live with the seasons and master the patterns of mounding earth, carving the land into plots, shifting earth for rice paddies, singing songs to the dry-time, making sun by stringed instrument, letting our songs drip in alternating patterns until our souls were soaked when the rains came.

We knew every tree, mushroom, fruit, and their uses. We had middens and used ashes, chicken and goat manure to keep the ancient soil fertile from year to year. Over millennia we practiced to near perfection the art of living on and with the land. We the Fulani ranged our cattle; we the Kongo climbed the raffia palm; we the Asante and Igbo brought yams out of the earth; we the Mende and Temne threshed rice; and we the Bozo set our nets out on the Niger. We fed ourselves and made a life to dance by.

THE GROANING TABLE

From the gardens and our fields came our groaning tables. Springtime brought mustard and turnip greens and rabbits and young chickens to be fried, shad in some rivers and herring in others. There were dandelion greens, lamb’s-quarters, and poke salad, and they would clean you out from the top of your head to the bottom of your feet. Crawfish came out of hiding, and our plates were filled. Late spring brought new potatoes and green onions. Summertime was what everyone waited for. Supper on the grounds in the summer meant lemonade and iced tea, sometimes with mint, punches and shrubs made from crushed berries, tomatoes and bell and hot peppers, cantaloupes and watermelons, fresh field peas and more potatoes. We had potato salad, fried chicken, deviled eggs, coleslaw, skillet-cooked squash, and rice a thousand ways. Blue crab time became barbecue time, and with it green corn time, until the harvest of the crops and corn and sweet potatoes brought their own glories. Winter moved us from hog killing time to the oyster months and possum and yams, turkeys, venison. Dried field peas, cabbages and turnips and sweet potatoes in banks, jars of put-up spring and summer produce—this is what got us through the winter.

Remember the orchard? Clingstone peaches, Chickasaw plums, Stayman Wine-saps, and Seckel pears planted when we first knew freedom: life-giving, sustaining fruit. Those vines in the grape arbor were muscadines and scuppernongs and fox grapes that your great-great-grandmother put the good store-bought sugar loaf to so she could make the communion wine. Nobody ate the fruit off the tree without threats of sickness. Once the summer treats of cobblers and the fall treats of pies were made, crocks and jars formed a rainbow in the pantry. A few cloves here, broken cinnamon sticks there, allspice, nutmeg, bits and pieces of worlds they would never see.

FORCES OF NATURE

My great-grandfather planted forked sticks in the soil—said a prayer, thrust it in the ground at a crossroads, didn’t look back. In his time, when you found an “Indian” arrowhead, you said it came from thunder in the sky, and put it around your neck to keep from being lynched. These were the men who threw seed in paths to guarantee a healthy newborn. These were the women who chose names by divination from the Scriptures. These were the ancestors, with pockets filled with cottontail feet, John the Conqueror root, and the good witch hands of sassafras. Their necks were strung with asafetida bags to keep off sickness. They pierced dimes to hide them from the evil eye. They smelled of crushed basil planted by the front door to keep the devil and the men without skins away.

The injustice was ugly, but the fields were gorgeous. Nobody hated green. Ever seen a field of pretty tobacco? Sap-swollen leaves masquerading faintly of mint on a hot Maryland or Virginia or Carolina afternoon? When cotton was in blossom, the flowers would be born and die in the same day, changing colors like costumes until the bud was left that would become in time a boll and everything from Carolina to Tennessee to Texas knew snow in boiling heat. Rice fields had a shimmering green and later a golden husk that battled birds for survival, and cane grew as tall as the tallest man could not grow down in Louisiana, Georgia, and Florida, promising syrup and liquor after the rest of the crop was sold.

OUR OWN KIND OF FREEDOM

From our homesteads in Oklahoma and Kansas to our cabins in West Virginia and Pennsylvania, we knew how to take care of each other. That was the number one dictate of the land: love the others on it just as you love the land and those who gave it to you in trust. Our values were there—to work and celebrate cooperatively, to have humor when it felt like there was none, to decorate our lives with the love we never received outside. In our spaces we were Father not boy, Mother not gal, Elder not uncle or aunt. We took the labels off of racist products. We made a world in our image. From our image we knew our Creator.