CHAPTER 11

Purging Glucose Shocks from Your Diet

Starchbusting is the name of the game. You don’t have to worry about mild-glucose-shock foods like apples, oranges, grapes, beans, peas, and tomatoes. Just like you always thought, most fruits and vegetables are good for you; they are full of soluble fiber, sterols, fatty acids, and vitamins that improve insulin resistance, lower blood cholesterol, and generally outweigh whatever potential they have for raising blood-glucose levels.

All you have to do is eliminate a few foods that have very high ratings—that is, over 100—and you’ll put a huge dent in your glucose shocks.

COMPARING OLD FOOD HABITS WITH THE NEW LOW-CARB WAY

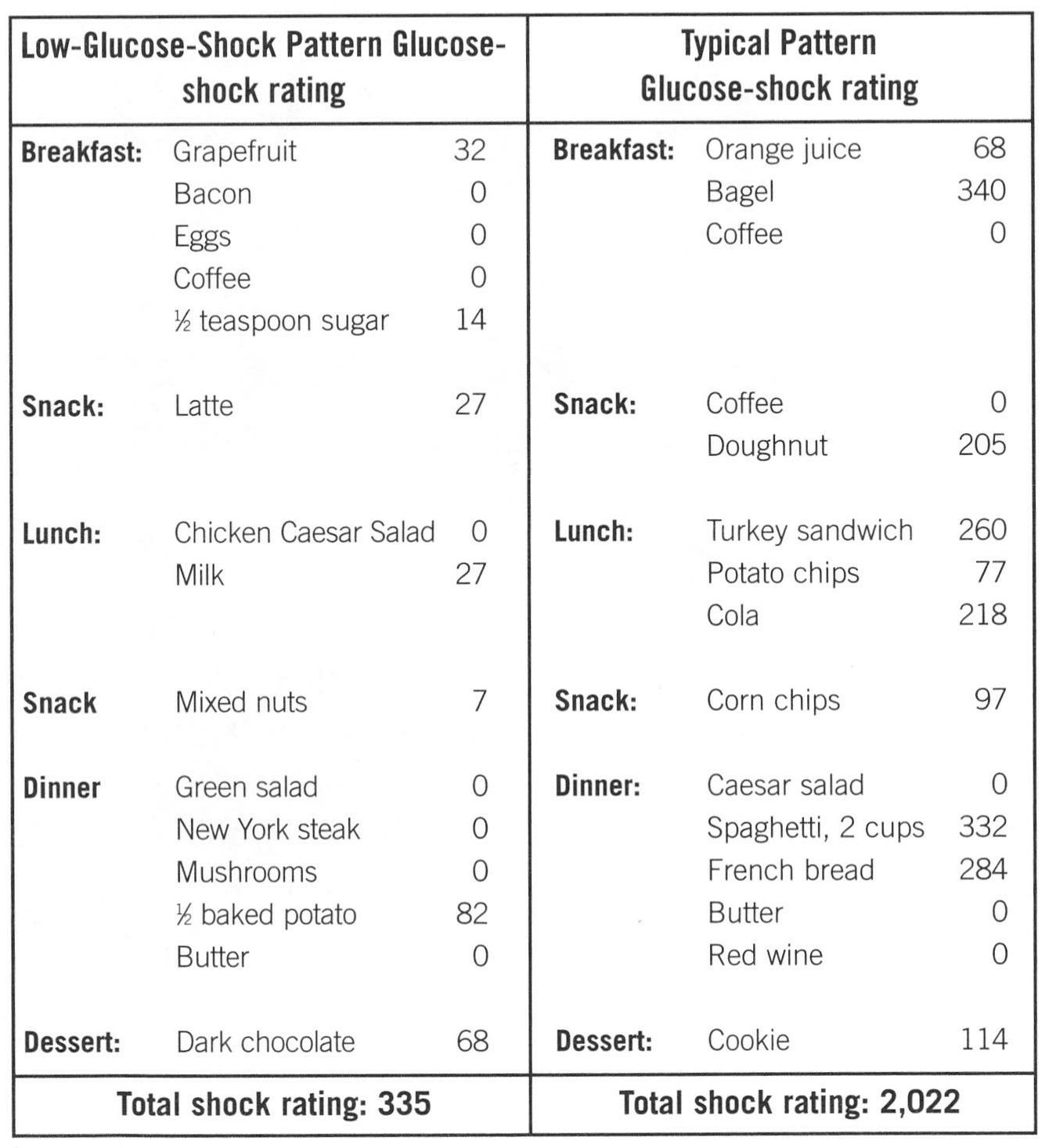

You can see how starch busting works by comparing glucose-shock ratings of a person eating heartily but avoiding very high glucose-shock foods with one eating more typical fare.

The Bagel Effect

You can see how quickly glucose shocks add up when you eat starchy foods and sugary soft drinks. I call this the Bagel Effect because the glucose shocks in one bagel exceed those in several days-worth of fruits and vegetables. Knowing how this works makes eliminating glucose shocks easy because there are dozens of moderate-glucose-shock foods (with ratings from 50 to 100) but only a few high-glucose-shock ones (ratings higher than 100).

CHOOSING LOW-GLUCOSE-SHOCK FOODS

FOODS YOU CAN EAT:

Red meat

Poultry

Fish

Seafood

Milk

Cheese

Butter

Margarine

Mayonnaise

Sour cream

Eggs

Salad dressing

Nuts

Apples

Oranges

Grapefruit

Grapes

Pears

Peaches

Plums

Cherries

Raspberries

Strawberries

Blueberries

Beans

Lettuce

Mushrooms

Asparagus

Artichokes

Cauliflower

Cucumbers

Peppers

Peas

Broccoli

Spinach

Tomatoes

Apricots

FOODS YOU SHOULD AVOID:

Bread (buns, rolls, crusts, scones, cookies, cakes, crackers, tacos, etc.) Potatoes

Rice

Corn products

Breakfast cereals

Pasta

Cola and fruit juice

Candy

If you compare the lengths of the two lists, you’ll see that if you don’t have to screen out moderate-glucose-shock foods, you have a wide variety of things to choose from. Simply concentrate your efforts on eliminating flour, potatoes, rice, corn, and sugar.

Follow These Tips for Eliminating Glucose Shocks

As you seek to eliminate glucose shocks from your diet, you’ll find that using these ideas will enhance your chances of success:

- ▶ Don’t try to eliminate starches entirely—just satisfy your craving. We all crave something sweet now and then. Candy, of course, satisfies this urge—but so does starch. Salivary amylase, an enzyme in your saliva, breaks down some starch while it’s in your mouth and releases a small amount of glucose. This stimulates the same taste buds as sugar.

Your craving for starch may be simply a craving for something sweet. But you won’t need to eat a plateful of starch to satisfy the urge. If you hold off starch consumption until the end of your meal—make it dessert—and eat about a fourth of what is customarily served, you won’t need much to satisfy your craving.

- ▶ Make sugar your ally. Even though you want to eliminate as much sugar from your diet as possible, you can still regard sugar as a friend. Sugar is four times sweeter than glucose. That means it takes only one-fourth as much sucrose to satisfy a sweet tooth as glucose. If your starch craving is really a longing for something sweet, sugar can satisfy it more effectively and with less glucose shock than starch.

Many advocates of low-glucose-shock eating (me included) encourage sweets in moderation. This means that you should eat only the sweets that contain very little starch; examples are semisweet chocolate and hard candy. Avoid flour-based confections such as cookies, cakes, and pies.

I recommend a small amount of chocolate—less than one hundred calories—once a day after a meal. You may find that being able to look forward to something sweet after a meal helps you pass up bread, potatoes, and rice. Chocolate has plenty of fat in it, but this isn’t about fat. There’s some sugar in chocolate but not much; and you taste every gram of sugar in chocolate because it’s not mixed with tasteless starch.

- ▶ Expect to spend more money or time preparing food. When you’re getting rid of starches, you’ll probably spend more money on groceries, or more time preparing food (instead of eating out). But think about what you’re actually losing—starch provides no flavor and no consistency, just calories. A low-glucose-shock diet requires only that you remove tasteless paste. The good stuff—fruit, vegetables, meat, dairy products, nuts, even some candy—stays. All you have to do is regain your taste for good food in its pure form, undiluted by starch.

This change in diet may cost more money and/or more time because starch is are cheap, and you may have been saving money by filling your refrigerator and pantry with bread, potatoes, and rice instead of fruit, vegetables, meat, and dairy products. Letting restaurants prepare meals for you saves time, but don’t forget that all eateries want to make a profit—and they can reduce costs by feeding you starch. To eliminate glucose shocks, you have to spend more money on food or take more time in food preparation.

Basically, you pay now or pay later. Invest in your health today, and you make up the expense in reduced medical costs later.

- ▶ Develop a daily rhythm. Try to work with your body’s internal clock. Hormone levels and brain metabolism fluctuate according to a twenty-four-hour cycle. If you follow a regular daily eating pattern, your appetite centers adjust to that rhythm and expect certain amounts of food at particular times of the day. If you miss a feeding, your stomach growls, and your metabolism begins to fall into starvation mode. Eat more than you are accustomed to, and you’ll feel overfed, and your body will convert those excess calories to fat.

Develop a daily pattern and stick with it. Unless you are doing hard physical work, the rule should be two small meals and one big meal every day. For most people, that means a light breakfast, a light lunch, and a full dinner.

- ▶ Eat breakfast. Curiously, most overweight people don’t eat breakfast. And that’s the opposite of the way it should be, because breakfast, if it doesn’t consist of high-glucose-shock foods, curbs your eating for the rest of the day. When researchers fed experimental subjects omelets for breakfast, these people consumed fewer calories per day than ones who skipped breakfast.

So, make a point of eating three meals a day. It gives your metabolic machinery something to work on and keeps it from slipping into starvation mode. When you skip meals, your metabolism slows down, and you overcompensate by eating more later.

- ▶ Don’t eat high-glucose-shock foods on an empty stomach. Make your between-meal snacks low-glucose-shock. Even a small amount of starch or sugar gives you a glucose shock if you consume it on an empty stomach. Examples of snacks that won’t cause glucose shocks are nuts, most fruits, vegetables, jerky, hard-boiled eggs, and cottage cheese. The time to satisfy a sweet tooth is after a meal.

TAKING SEVEN STEPS TO LOW-GLUCOSE-SHOCK EATING

In a low-glucose-shock diet, the few taboos are easy to recognize. Reduce the amount of bread, potatoes, corn, rice, and sugar in your diet, and you’ve removed most of the glucose shocks.

The following steps will help you reduce glucose shocks with little inconvenience and deprivation.

Step 1. Eliminate starchy entrees and fillers

You probably consume starch as entrees—pasta, sandwiches, pizza—or as fillers that accompany entrees—bread, potatoes, rice, french fries. Those fillers should be the first to go.

That doesn’t mean you should eat less food. Just replace those fillers with other things—meat, vegetables, salads, nuts. Add a side dish of soup or salad, and push away the potatoes.

You may be wondering if you can get away with eating less starchy forms of the same food, like whole-wheat bread instead of white, or brown rice instead of white. In reality, all forms of bread, potatoes, and rice are bad. None of them has an acceptable glucose-shock rating. My advice? Try to lose your taste for these foods. It will happen if you let it.

The good news is that reducing your intake of starchy fillers is not a particularly awkward or logistically difficult thing to do. Look around you the next time you’re eating with a group of people; you’ll see some of them pass up the bread or push part of their potatoes aside. You aren’t expected to eat all of the starch that’s served to you.

Step 2. Choose beverages wisely.

Even if the rest of your meal is healthy, if you wash it down with cola or fruit juice, you get a glucose shock. Also, the calories in soft drinks add to rather than replace calories supplied by other foods. Researchers have found that when experimental subjects add solid sweets, such as jellybeans, to their diet, they tend to reduce their intake of other foods, but when they add the same amount of sugar in the form of a beverage, they continue to eat the same amount.

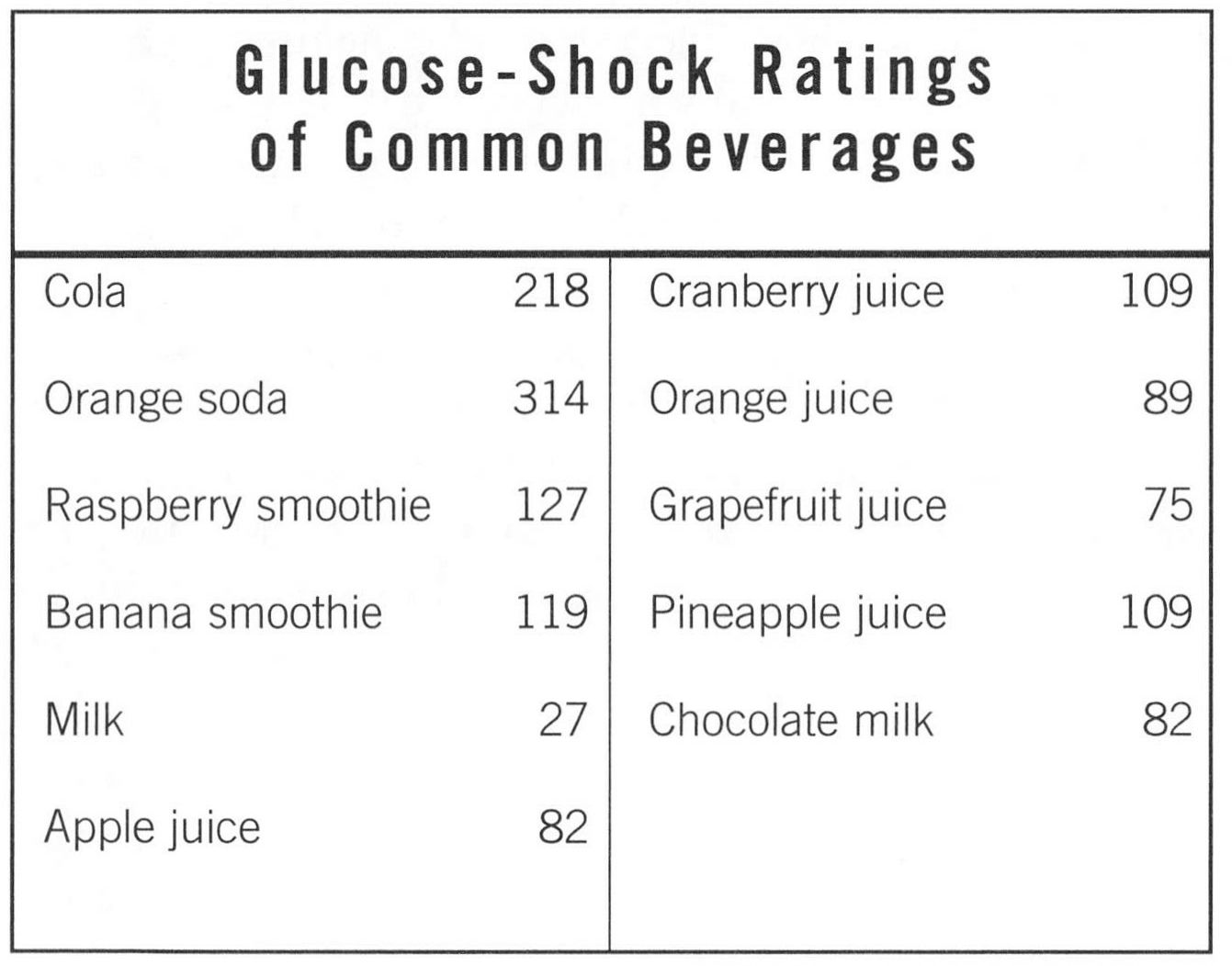

Here is a list of glucose-shock ratings of some popular beverages:

Here are some other beverage tips:

- ▶ Diet drinks are okay. They won’t give you a glucose shock. However, they stimulate your taste buds and send false messages to your brain that food is coming, which stimulates hunger.

- ▶ Go easy on fruit juices. Most of these cause glucose shocks, but fruits in their natural form don’t. The juicing process removes fiber and disturbs the fine structure of fruit, which raises its glucose-shock rating. You shouldn’t drink more than six ounces at a time.

- ▶ Enjoy homemade smoothies. Blend fresh, whole fruit with milk or yogurt. Use no sugar and you’ll have a delicious drink that won’t cause a glucose shock.

- ▶ Drink coffee but understand that it can stimulate stomach acid and make you feel hungry. Don’t worry about adding a little sugar. A potato releases more glucose into your bloodstream than do twenty teaspoons of sugar.

- ▶ Alcohol in moderation is all right. Red wine, white wine, and spirits add calories but don’t raise your blood-glucose level. However, the nonalcoholic contents of many mixed drinks can. Beer and most mixers, including tonic and ginger ale, are full of sugar. One caveat: alcohol blunts the brain centers that tell you when you have had enough to eat, which means you are likely to eat more food when you precede meals with alcohol.

- ▶ Drink milk. This is an excellent beverage if you’re trying to avoid glucose shocks. Fewer milk drinkers have diabetes and obesity than non-milk drinkers.

Step 3: Eliminate all breakfast cereals except 100-percent bran. The glucose-shock rating of a bowl of 100-percent bran cereal is 85, which, unlike other cold cereals, isn’t quite enough to give you a glucose shock. You may, however, push it too high by adding sugar, bananas, or raisins. Instead, add low-glucose-shock blueberries, raspberries, or artificial sweetener. Also, stay away from 40 percent bran or Raisin Bran, which are generously amended with processed flour and pack large glucose shocks.

Remember those Wheaties, Cheerios, and Sugar-Frosted Flakes commercials we were bombarded with when we were kids? Advertising told us that grain-based breakfast cereals were good for us, but they aren’t, because they deliver huge sugar shocks. The glucose-shock ratings of most breakfast cereals—including Cornflakes, Grapenuts, Cheerios, Rice Krispies, and shredded wheat—exceed 125. Even oatmeal is bad. Its rating is 154, higher than Sugar-Frosted Flakes.

Unfortunately, many of us start each day by throwing our metabolism off balance with a big glucose shock. Mornings have become a time for grain products—cereals, toast, bagels, buns, and scones. Ironically, as maligned as the traditional bacon-and-eggs breakfast is, this is probably a better way to go. Start your day with eggs, breakfast meats, fruit, yogurt, or cottage cheese instead of grain-based items. (Cereal’s only redeeming quality is fiber.)

Step 4: Add fiber to your diet.

Cereals with fiber, on the other hand, may be worth a slight glucose shock. Here’s why:

- ▶ Fiber, the indigestible parts of plants—the skin, husks, and pulp—come in soluble and insoluble, both good for you in different ways. Fruits and vegetables are full of the soluble kind, but insoluble fiber is much harder to come by. In Western countries, the only good source of insoluble fiber is the husk of the wheat kernel, called bran, and the easiest way to get this is by eating bran cereal.

- ▶ Bran increases the amount of fat excreted in the stool, offsetting the calories it provides. That makes it the only common food that actually takes away calories.

- ▶ Lack of insoluble fiber is the only common, disease-causing dietary deficiency in industrialized countries. Inadequate amounts predispose people to irregular bowel habits and a number of aggravating digestive diseases, including irritable bowel syndrome, diverticulitis, hemorrhoids, and colon cancer.

Step 5: Reduce refined carbohydrates in entrees.

To reduce glucose shocks from starch-containing main dishes, eat fewer such entrees, and cushion the glucose shocks when you do eat them.

Here are some tips on meal timing and dietary approach:

- ▶ Reduce starch-containing entrees to twice a week for dinner and twice a week for lunch. For a week’s worth of dinners, have pasta one night, a fast-food hamburger another, but for the rest of your evening meals, stick with meat, vegetables, eggs, and dairy products. For lunches, eat a sandwich for lunch one day, pizza another, and soup but salad on the other days.

- ▶ Eat your vegetables first. The order in which you eat foods is important in avoiding sugar shocks. High-fiber foods like salads slow the digestion of starch. In addition, delaying your starch intake until later in a meal gives your appetite centers time to respond to more slowly digested foods. It is a healthy habit to start meals with a salad. Meticulously avoid eating refined carbohydrates on an empty stomach. Nibble at starches and sugar only after you have consumed most of your meal.

- ▶ Deconstruct your food. Pasta dishes, sandwiches, pizza, and deep-fried foods contain lots of starch, so pick them apart. For example, not only can you bypass pizza crust, you can take it a step further—scrape off the cheese and toppings and eat them by themselves. You can significantly reduce glucose shocks by eating sandwiches open-faced, peeling off deep-fried crusts, and pushing starchy parts of entrees aside.

- ▶ Build a “starch pile” on your plate. Pick away a good portion of the refined carbohydrates, and place them in a pile along with some of the starchy fillers. Then, enjoy the rest of your meal. When you’ve finished eating the good stuff, you will find that the starchy stuff doesn’t look as appetizing as it did at first. As you leave the table, you can take satisfaction in knowing that you avoided consuming an overdose of starch.

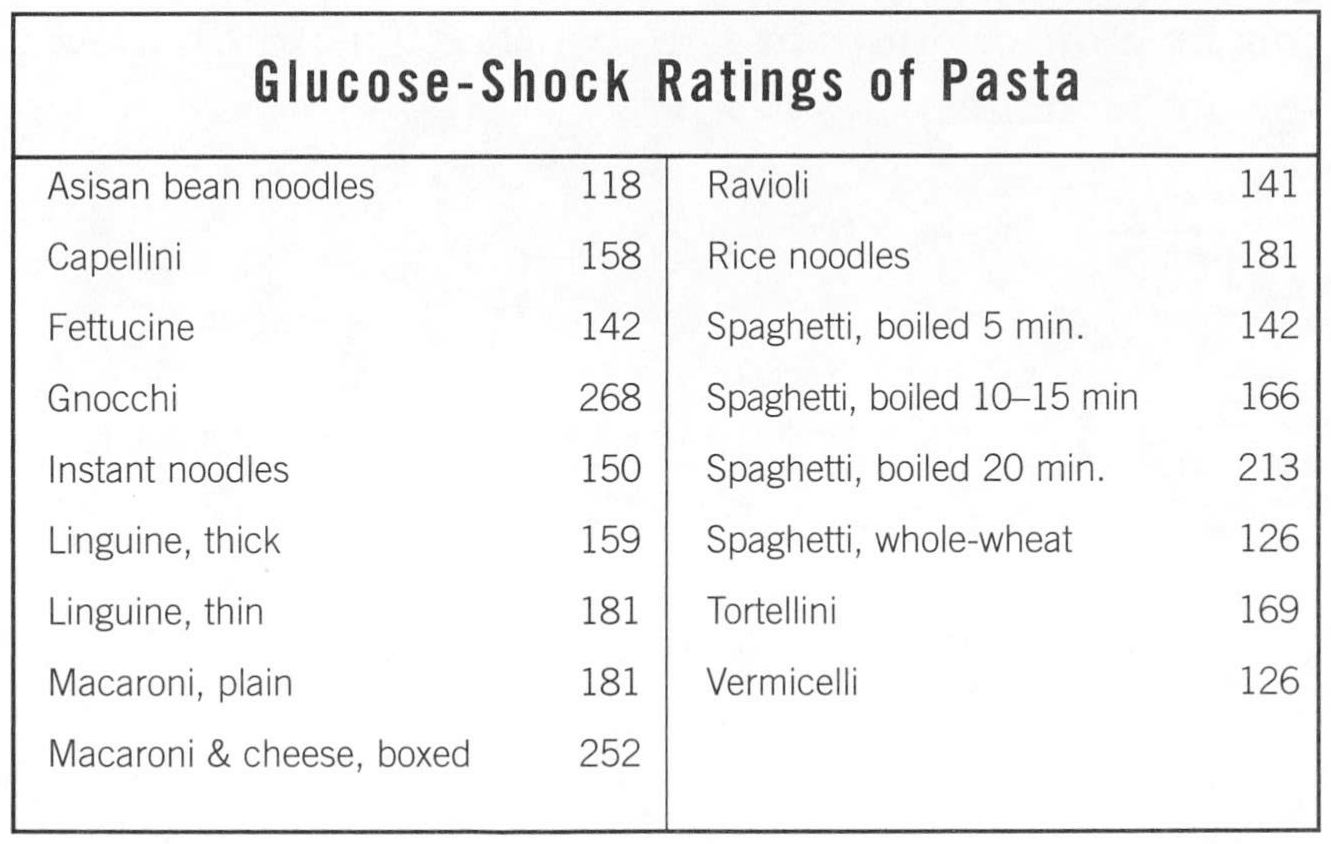

- ▶ Eat pasta al dente, with plenty of extras. I’ll assume you’re like me: you love pasta and don’t want to give it up. But full of starch, and you should avoid it as much as you can. However, pasta has some redeeming qualities. Some kinds deliver less of a glucose shock than others, and there are ways to prepare pasta that can cushion its impact.

Your intestinal tract digests pasta more slowly than it does other kinds of starch. Flour consumed in pasta causes less of a glucose shock than similar amounts eaten as bread. This is especially true if the pasta is cooked al dente—lightly, to maintain firmness. For example, the glucose-shock rating of spaghetti boiled five minutes is 142, which is permissible, but the rating rises to 166 if cooked ten minutes and 213 after twenty minutes—enough to give you a large glucose shock.

Some pasta dishes are heavy with sauces of meat, vegetables, and olive oil, which is good, because the fewer calories you get from pasta and the more from other ingredients, the less starch you will be eating.

As a rule of thumb, pasta with meat contains about half as much starch per calorie as plain pasta. A half-plate of spaghetti with meatballs is as filling as a full plate of spaghetti alone but contains only half as much starch.

The table below lists glucose-shock ratings of various kinds of pastas. In general, the larger the noodle, the lower the rating. Note that gnocchi—a potato pasta—has the highest glucose-shock rating of all, with rice pasta running a close second.

Step 6: Choose whole-grain products if you have to eat baked goods.

Bread is such an integral part of American and European dietary tradition that saying it’s unhealthy is almost a sacrilege. But, it’s definitely bad for you. When it comes to causing glucose shocks, nothing is worse.

Most people in Western countries get most of their glucose shocks from bread. Ounce for ounce, bread delivers larger glucose shocks than pure granulated sugar. The next time you eat a slice of bread, think of eating a pile of sugar because it has about the same effect on your body.

If you want to reduce glucose shocks, you must reduce your consumption of breads, rolls, biscuits, bagels, cakes, pastries, crackers, and crusts. In those rare instances when you can’t avoid them, choose whole-grain products. And by “whole grain,” I don’t mean “brown” bread but bread made of whole-grain kernels like cracked wheat or stone-ground flour.

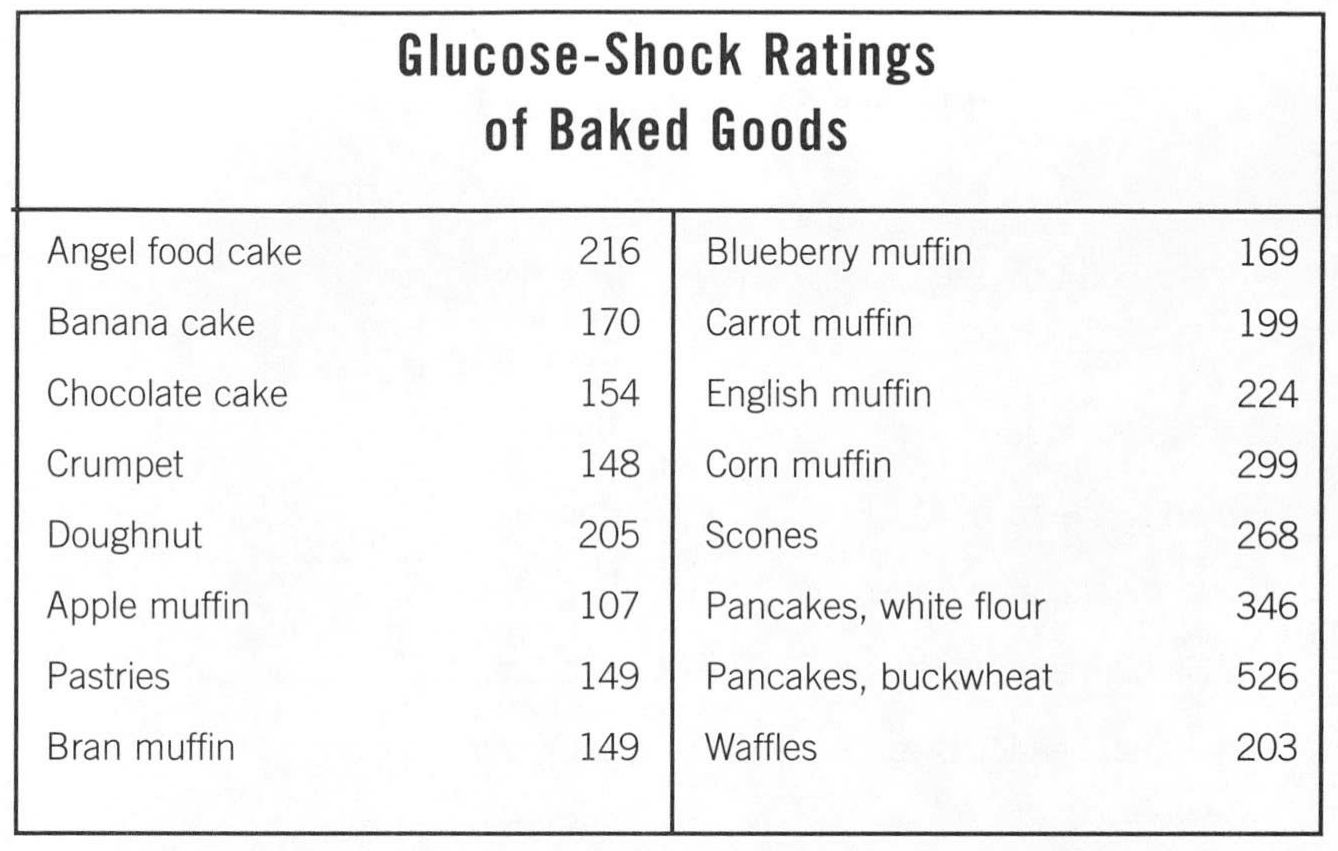

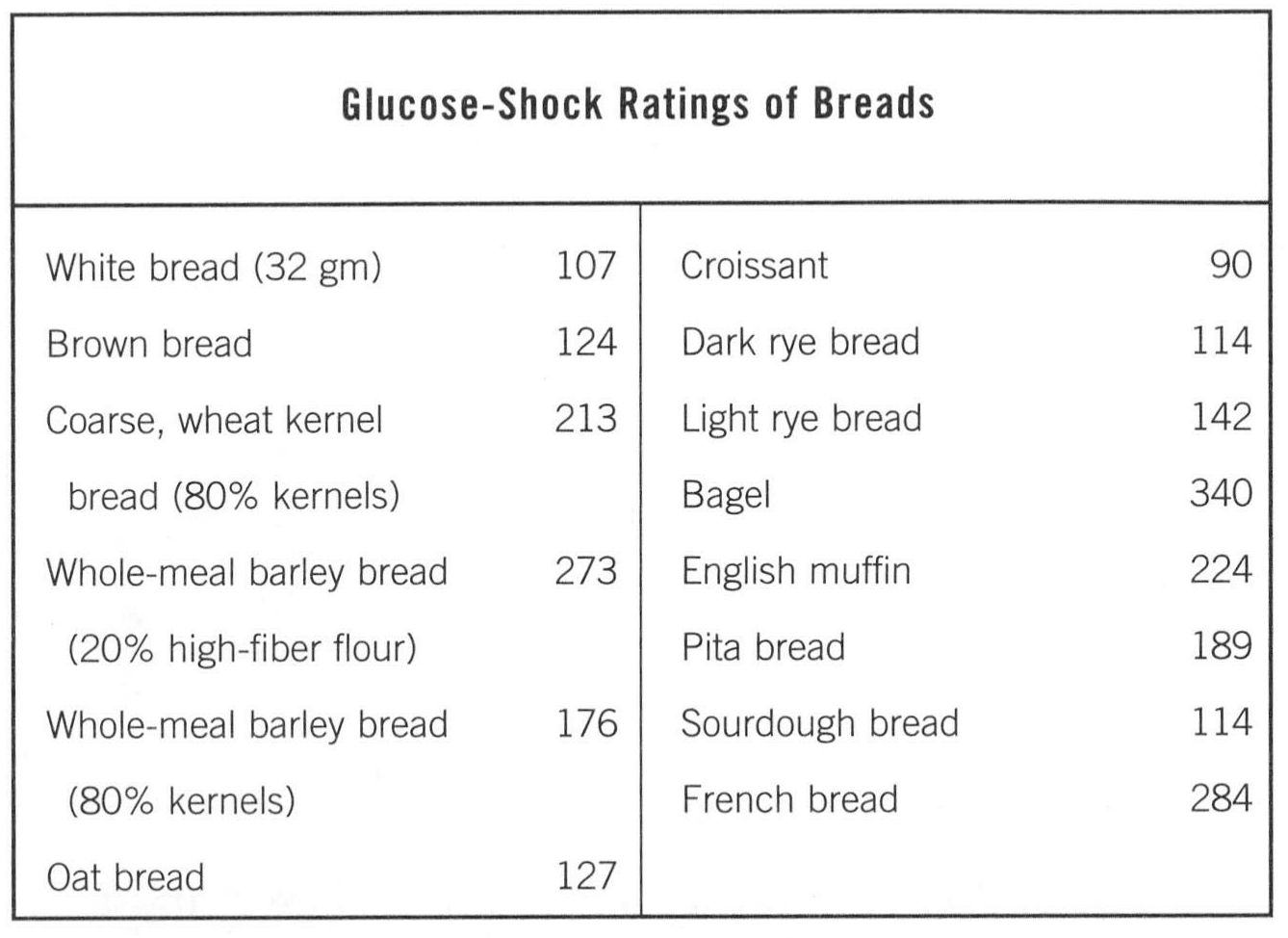

Here’s a list of glucose-shock ratings for breads. Notice that, contrary to popular belief, even most whole-grain products have unacceptable ratings. Although they release glucose more slowly than white bread they are heavier and contain more calories and carbs per slice. They do, however, contain more fiber.

Cakes and pies, because they are flour-based and generously laced with sugar, are generally bad, but some are worse than others. Review the following list of popular baked goods. You may wonder why the glucose-shock ratings of some notoriously sinful delights are less than those of white bread. For example, chocolate cake—a synonym for self-indulgence—has a rating of 154, compared to 224 for an English muffin. That is because it’s starch, not fat or sugar, that pushes the shock ratings of most baked goods into unacceptable ranges.

Step 7: Learn how to snack wisely.

You’re not perfect. Occasionally, you’re going to cheat, but if you’re crafty, you can exert damage control.

Follow these snacking guidelines:

- ▶ Stay away from cookies, crackers, pretzels, popcorn, and candy bars (except those that are pure chocolate).

- ▶ Eat nuts. These universally favorite snacks deliver no glucose shocks at all. In fact, eating nuts isn’t cheating at all. They are rich in protein and fiber and won’t raise your blood-glucose level. Stock your shelves with every kind of nut you like and reach for them whenever you get the urge to snack.

- ▶ Treat yourself to chocolate. The glucose-shock rating of two, one-inch squares of chocolate is 61, well within the safe range. It has sugar in it, but the sweetness is not diluted by tasteless starch. You get to savor it all. It also has plenty of fat, but if you’re just trying to reduce glucose shocks, you don’t need to worry about fat. A little chocolate after a meal—especially if it’s semisweet—won’t give you a glucose shock, and if the satisfaction prevents you from eating worse things, it’s worth a few extra grams of sugar.

- ▶ Choose hard candy. You can savor all of the sweetness of the sugar in it and satisfy your sweet tooth with an inconsequential amount of sugar. The only problem is that it stimulates your taste buds without delivering many calories, which stimulates your appetite. So, munch hard candy only after a meal.

- ▶ Treat yourself to some ice cream occasionally—it’s not the worst thing you can do. Sugar and starch, not fat, determine glucose-shock rating, and although ice cream contains plenty of fat, some brands are acceptably low in sugar and starch. If you’re trying to avoid glucose shocks, don’t bother with low-fat ice cream or frozen yogurt, which have glucose-shock ratings as high as regular ice cream but aren’t nearly as satisfying. Frozen tofu has one of the highest glucose-shock ratings of all.

LOW-GLUCOSE-SHOCK EATING ISN’T HARD

Be honest. Would you call reducing glucose shocks deprivation? Would eating a steak and a salad instead of spaghetti and French bread be unbearable? Would pushing potatoes to the side of your plate and having some chocolate for dessert ruin your dinner?

Low-glucose-shock eating is an intrinsically satisfying way to eat. You get more taste and texture from your food when you don’t dilute it with tasteless starch. And you don’t have to be a food expert to follow a low-glucose-shock diet. It’s such a healthful and practical way of eating, you may not be able to find excuses for not following it.

Take the steps suggested and see how well your body cooperates. Unless you’re a complete couch potato, your triglyceride level will fall, your good cholesterol level will climb, and you will steadily and comfortably lose weight at a rate of about two to four pounds a month—just enough to shed fat without slowing your metabolism. It works. I’ve seen it countless times.

Don’t Neglect the Other Parts of Your Diet

A low-glucose-shock diet helps the carb side of your body chemistry, but what about the cholesterol side? If your body has trouble removing cholesterol from your bloodstream, low-glucose-shock eating alone may not be enough. You might need to modify your fat intake, and I’ll show you how to do that in chapter 12.

Even if you don’t have high blood cholesterol, it’s important to have a dietary strategy that encompasses fats and carbohydrates. Changing the way you approach one part of your diet is easier and more effective if you have a good plan for the other.

KEY IDEAS FOR TAKEOUT

- ■ The glucose-shock ratings of refined carbohydrates dwarf those of fruits and vegetables.

- ■ The best way to reduce glucose shocks is to concentrate on those few foods that have very high glucose-shock ratings and don’t worry about midrange glucose-shock foods like apples, oranges, grapes, beans, and peas.

- ■ Concentrating on the very high glucose-shock foods makes reducing glucose shocks easy because there are dozens of moderate-glucose-shock foods (glucose-shock ratings of 50 to 100) but only a few high-glucose-shock ones (ratings higher than 100).

- ■ The worst offenders are starchy fillers: bread, potatoes, and rice.

- ■ Sweets that aren’t mixed with starch, such as chocolate or hard candy, contribute little to total glucose shocks.

- ■ The only cereal that doesn’t deliver a large glucose shock is 100-percent bran cereal.

- ■ All breads have unacceptable glucose-shock ratings.