CHAPTER 8

Disaster

Living beside a river can be interesting, exciting, and fun. But sometimes, when the rains come and the river pours onto the land, it can cause disasters. The Great Flood of 1927 was one of the worst floods ever recorded.

The rains began in the winter of 1926. Streams and rivers from the Rocky Mountains to the Appalachian Mountains swelled higher and wider. Water overflowed their banks and rolled downward. The rain kept falling, in the North, the West, the East, through the winter and into the spring, harder and harder.

People in Kansas, Oklahoma, Illinois, Kentucky, and other parts of the Mississippi River basin were worried. Would it ever let up? It seemed like water was rushing downstream toward them from everywhere.

People who lived close to the Mississippi River were even more frightened. Swollen tributaries were draining so much water into the Mississippi. If the rain didn’t stop, the Mighty Miss would overflow, too.

The rain kept falling. By March of 1927, the water in the Lower Mississippi was as high as the riverbanks. People were afraid the levees built by government workers would break. (Levees are walls along riverbanks built to hold back rising water.) What would happen if they collapsed? Water would flood the land.

Levees

The Army Corps of Engineers promised the levees would hold. Most people believed them. The engineers had built the levees, so they should know.

By April, the Lower Mississippi was at record highs and the water was still rising. People were told to leave their homes and head for higher ground. Many did. Others stayed. Later, as the water spilled from the river, the people who had stayed realized they had made a mistake. This flood was turning out to be worse than any other flood in history.

Then, on April 15, the rain began to fall all over Central and Southern states like Missouri, Illinois, Arkansas, Mississippi, Texas, and Louisiana. More than fourteen inches fell on New Orleans that day.

On April 16, 1927, the swollen Ohio brought even more water into the Mississippi at Cairo, Illinois. Thirty miles south, a twelve hundred–foot levee collapsed. Water from the river flooded 175,000 acres of land. Soon many more levees began to break. One after another, levees along the Mississippi River fell.

Churning, swelling water was exploding against levees on both sides of the Mississippi. People in towns on opposite sides of the river each hoped the other town’s levee would collapse first. That side of the river would flood, but their side would be safe. There were fears of people sneaking across and knocking down a levee. Night after night, villagers stood guard.

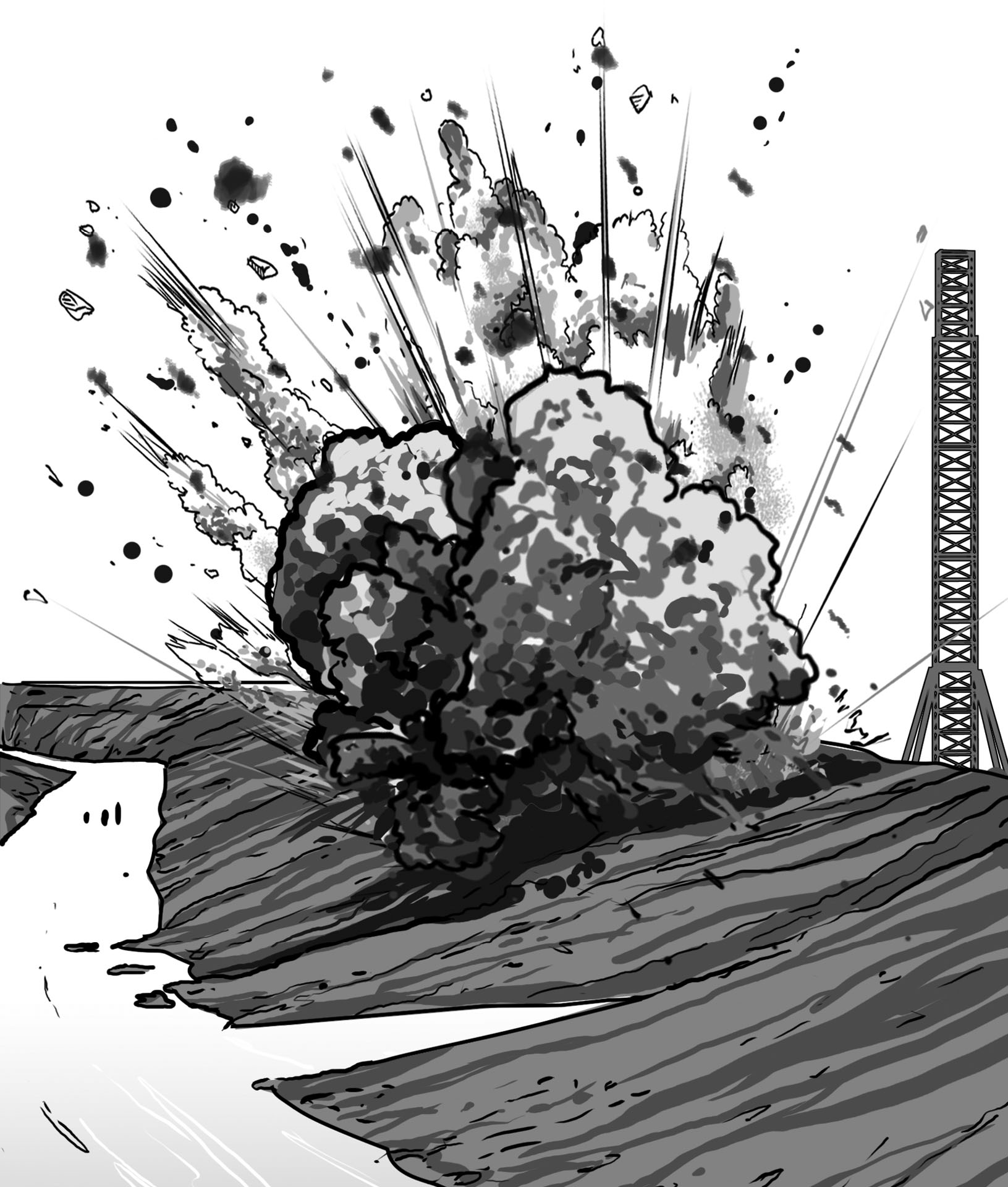

In New Orleans, workers tried to keep back the water by blasting a hole in a levee. The plan worked. The water flowed through the hole to a safer place.

The town of Greenville, Mississippi, got the worst of it. The rain would not stop. Swift water from the Ohio, Missouri, and Arkansas Rivers had thundered into the swelling Mississippi. The water was coming. Greenville was in the worst possible spot it could be.

On April 21, river water near Greenville rose so high, it toppled all the levees, and by the next day the town was flooded with eight feet of water. Ten days after that, one million acres of nearby land were flooded ten feet high.

Some people left town to search for higher ground. Some climbed trees or waited for help on rooftops. Some scrambled to hold back the river by stacking sandbags to work as makeshift levees. But it was no use. The rain kept coming and the water continued to hurry across the land.

By the time the storm ended, twenty-seven thousand square miles of land in the middle of the United States was flooded.

One woman who was there wrote this account in a Greenville paper:

“As the water drew nearer it ceased to glitter, it was horrid, dirty water filled with bugs and crayfish and snakes and eels. The thought of that messy water coming into one’s home was just too much to endure, and yet, there was not a thing on earth anyone could do except watch it come, to the street, to the walk, to the house, then up, up, steadily and inexorably up for a week.”

It took a long time for the Mississippi River basin area to recover from the Great Flood of 1927. Some towns never were the same. Homes were washed away. Crops on either side of the Mississippi were destroyed. Big cities were under water.

Three hundred thirty thousand people had to be rescued from attics, treetops, and other high places. No one knows how many people died, but some people estimate it was as high as one thousand.

Something had to be done. More floods would come in the future. Some might even be worse than the Great Flood of 1927. It was clear that levees were not capable of holding back the river during huge storms.

A year later, the United States government passed the Flood Control Act of 1928. The Army Corps of Engineers would be in charge of finding new ways to control Mississippi River flooding. They did build stronger and higher levees in some places, but the engineers thought of other ways to control water and direct it away from cities. They remembered the hole that had been blasted in the New Orleans levee. Water had moved to a safer place. They decided to use the same idea to create spillways and floodways. Spillways are concrete structures by the river with many steel gates that can be opened to let out water safely. When the gates are open, water flows through floodway channels that have been cut in the land. Floodway paths lead to specially chosen safe areas of land.

A spillway

Engineers would rather not flood any land, so Mississippi River spillways are only used in cases of extreme emergency.

The Morganza Spillway is about fifty miles north of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. It was completed in 1954, but it wasn’t used until a massive flood in 1973. Forty-two of the 125 gates were opened to release the water and direct it away from the city. It worked.

New Orleans is a huge city that spreads out north of the Gulf of Mexico. It is difficult to protect New Orleans from flooding because water completely surrounds it. The Mississippi River flows right through it. There are canals throughout the city, and Lake Pontchartrain lies to its north. Also, the city is built on land shaped like a soup bowl; the deepest part of the “bowl” is below sea level. Levees had been built around the canals and the lake. But they were very old and needed repairs.

In 1931, the Army Corps of Engineers built the Bonnet Carré Spillway, thirty-three miles north of New Orleans. To this day, the spillway and floodways divert water away from the city center. Water travels through Lake Pontchartrain, and on to the Gulf of Mexico.

But sometimes, nothing can hold back the water.

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina, the third-strongest hurricane ever to hit the United States, raged across the Gulf Coast. Winds blew at more than one hundred miles per hour. Many places in Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana were devastated.

In New Orleans, the Mississippi River levees held. They didn’t break. Some water did spill over the tops. That, however, was not the big problem. What caused so much damage and death was the collapse of levees around canals and the lake. Most of New Orleans ended up underwater. Nearly two thousand people died. Many left the city never to return. Even now, there is still much rebuilding to do. New Orleans’s location at the mouth of the Mississippi is why it became such a thriving, exciting city that tourists around the world flock to. However, its location has also been the reason for its near ruin.