CHAPTER 3

The Atlantic Provinces and Union 1857–1859

If Canada were to expand westward as a result of the federation proposed by the Canadian government in August 1858, it would be as the heir of a crumbling commercial concern. The seventeenth-century régime of commercial monopoly and company rule could not survive the advent of nineteenth-century settlement, whether from Canada or the United States. The passing of the Hudson’s Bay Company was likely to make Canada the unqualified legatee of the lands under British title from Labrador to the Rockies, an unpopulated, unorganized wilderness.

If, however, Canada were to expand eastward, it would be under very different circumstances and on very different terms. Between the Gulf of St Lawrence and the open Atlantic all the territory was occupied and organized. It was organized in four colonies, all self-governing under responsible government, three of which had traditions of self-government older than those of Canada. Each of the four colonies of Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, moreover, was a distinct community with a self-conscious identity and a strong local patriotism. Particularistic in spirit, regional in outlook, often parochial in sentiment, the Atlantic provinces were fiercely independent and still elevated by the heady political wine of responsible government.

This abounding particularism, however, flourished in an imperial framework. Independent as Nova Scotians or New Brunswickers might be, they were also imperial patriots who capped their local independence with an imperial allegiance which was the stronger for being tenuous. This imperial framework as yet supplied the Atlantic provinces with such degree of union as their needs required. While it did so, it remained a further obstacle, however slight, to Canadian union with the Atlantic region.

The four Atlantic provinces of British North America, then, were in their several ways studies in the effects of regional isolation and local patriotism. The oldest, Newfoundland, was also the most isolated and the most particular. A fishery since the sixteenth century, a colony with all the institutions of a colony only since 1832, it had a location, an economy, a history, and traditions either peculiar to itself or only partly reproduced in its Atlantic neighbours. Not only was it an island cut off from the continent by ice for six months of the year, it was also an island always open to the Atlantic, to the British Isles and the sun-filled Mediterranean, to the American sea roads and the sun-cherished West Indies. It faced eastward and southward and back upon history, not westward to a continental frontier and forward to continental growth. It was an Atlantic island, not an American land; maritime, not continental; British, not British-American; and not by any trace or connection, Canadian.

Its insular isolation was confirmed by the fishing economy. Newfoundland and the Newfoundlanders lived by the cod fishery. The taking and curing of cod engaged the full labour force of the island in the summer. Nearly the whole of the island’s income came from the sale of cod to the Mediterranean and the West Indies. In the spring the sealers put out to hunt over the ice floes of the Labrador Coast and the Gulf of St Lawrence. Except for this dangerous and precarious calling, there was little source of income other than the fishery. A little gardening, a scanty cultivation of potatoes where soil existed or could be built upon the rocks, a little pasturing of cattle in the Avalon peninsula, supplemented a diet of dried fish and imported flour, but added nothing to the cash income of the population. Minerals were reported in abundance in 1857,1 but none was yet mined in the island or its dependency of the coast of Labrador. Under pressure of population, the colonization of the west, or “French,” shore of the island had begun, but there the familiar pattern of fishing stations and potato fields was repeated. The widespread, if stunted, forests of the interior were untouched, except for local use. By far the greater parts of Newfoundland and Labrador were as primitive as when Cabot had first sighted their rocky coasts.

It was this concentration of all effort on the fishery that had given the island its peculiar history. The consequence was that Newfoundland was a constellation of outports centring on St John’s, the principal port of the Avalon peninsula and of the island. These scattered coastal villages, as primitive as their sonorous names were poetic, Carbonear, Bay Bulls, Harbour Grace, were isolated and self-contained, their people strangers to those of neighbouring villages, save as the men folk met at sea or on the Banks. The ties of the “Community of Newfoundland,” as they sometimes called themselves, were in consequence not social but economic, the bonds of indebtedness to the merchants and factors of St John’s.

The relations of St John’s and the outports were in some ways reinforced by the composition of the population of the island. In 1845 it numbered 96,295; in 1855, 122,638.2 The origins and religions of the population were two: West Country English and Protestant; South Country Irish and Roman Catholic. Both were brought out as fishing and curing crews, the latter an occupation in which women had a part. As fishing crews they had been left, or elected to remain, on the island over winter. Most made their way by fishing-ship or provision schooner to New England or Nova Scotia, but the ancestors of the Newfoundlanders of 1857 had remained, It was this process that had converted the summer fishery of Newfoundland into a permanent colony. The great Irish famine of 1845 and 1846 had sent a flight of Irish to the rocky coves of Newfoundland, and much of the increase since 1845 is surely to be attributed to that exodus. But the Irish immigration had fallen off after 1847, as Ireland’s population fell, and as unemployment and the potato blight increased in the island itself.3

The dual origin and the religious difference meant that the island’s population was divided sharply, and the division sharpened the relation between St John’s, dominated by merchants of West Country origins and ties, and those of the outports which were often mainly Irish Catholic. The racial and religious division and the operation of responsible government were creating, as in Lower Canada, a dual system of denominational schools. It made the politics of the island sectarian and racial; it added to the geographical dispersion of the people from harbour to harbour along the grandly indented coast, and to the lively cleavages of race, religion, and even language. In this, Newfoundland, like all its sister British-American colonies, was attempting to maintain, in representative and democratic government not yet a generation old, the subtle conventions and polite reservations of the ancient and profoundly aristocratic parliament of the United Kingdom. It was not surprising that “responsible government” in Newfoundland fell short of the refinements of Westminster, or that its governors, like those of other Atlantic colonies, sometimes despaired of making parliamentary government work in those small colonies.

Responsible government had been introduced in Newfoundland in 1855 by an enlightened and energetic lieutenant-governor, Charles Henry Darling.4 The result had been to bring to bear on government the local and religious divisions and jealousies of the island’s population. Responsible government, in the simple conditions of British North American life, was self-government by a local democracy. In Newfoundland the great majority of the population was so poor that the franchise, still based in theory on property, had to be very wide or extremely narrow. It had of necessity to be very wide to be representative of any but the merchants of St John’s, and was a mere householder franchise. In consequence of this the local democracies of the outports, largely Irish and Catholic, dominated the Assembly, although not the legislative council, and from their popular party the executive council in 1857 was drawn. The opposition in the Assembly was the “commercial party,” which had its leadership among the merchants of St John’s,5 and its rank-and-file support among the West Country English. These incipient “Liberal” and “Conservative” parties were neither coherent nor principled, but mere groupings of sentiment and interest. It was on their play, their formation and dissolution, that the entrance of Newfoundland into Confederation was to depend.

Westward from Cape Race was the province of Nova Scotia. This peninsula, with its island of Cape Breton, had little to do with Newfoundland, except to share its fisheries and to ship it provisions and lumber. But Nova Scotia had much to do with its neighbours, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. It was indeed the core of the ancient Acadia of which they had been part, and in strategy it was still their centre and superior. The War Office returns were made for “Nova Scotia and its dependencies,”6 and the lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia was still usually a general who was commander-in-chief of the forces in the other Atlantic provinces as well as those in garrison in the citadel of Halifax.7 That great harbour was also the summer base of the North-American squadron which showed the flag among the shipping of the international fishery, and in winter shifted to the tranquil waters of the British West Indies. Nova Scotia was first and foremost, as no other colony was and Canada least of all, an indispensable base of British military and naval power as then disposed. Of all British North America, only Nova Scotia constituted a vital British interest; all the rest was an imperial responsibility outweighing any advantage. This fact was to explain much in the attitude of Nova Scotia, and of the imperial government, toward a union of British America.

The imperial character of Nova Scotia was strengthened further by the fact that the province was not only part of the Empire, but also participated in the military, naval, political, and literary life of the Empire. In this very year 1857, T. C. Haliburton, a household name in the English-speaking world as the author of Sam Slick, was a member of parliament at Westminster and a figure in the literary world of London. Another son of the province, Sir William Fenwick Williams, still radiant with the fame won in his defence of Kars in the Crimean War, was also a member of parliament at Westminster, and something of a lion in London society. Still another Nova Scotian, one of the officers of HMS Shannon in her victory over USS Chesapeake, Sir Provo William Parry Wallis, was already a Rear Admiral and rising by slow and inevitable degrees to the rare and ultimate rank of Admiral of the Fleet. These three men were only outstanding examples of the way in which Nova Scotians circulated in the life of the great empire of which the province was so intimate a member.

This imperial patriotism was, however, very much a matter of the naval base of Halifax and the Tory pocket of Windsor. In Halifax, as in Quebec, the morning and evening bugles, the thud of the noon-hour cannon, and the warships riding dark and silent in the harbour beneath the citadel, signalled the martial character of the garrison city. And as in Quebec, the presence of the military and the navy brought into the life of the provincial capital an influential stream of metropolitan manners and metropolitan connections. Halifax was kin to Portsmouth or Plymouth, as much as to Montreal or New York.

The metropolitan tincture of Haligonian society spread to all business and professional circles, and was strengthened by commercial and legal ties. Samuel Cunard, still proprietor of a Prince Edward Island estate and of timber berths on the Miramichi, and drawn more and more to Liverpool and New York by the success of his line of steamships, was an outstanding example of the Haligonian commercial class. Like that of Boston, it was composed of far-ranging, shrewd-bargaining traders and enterprisers whose reach was as wide as the seas. And Haligonian lawyers were not content with a provincial practice and a local reputation. The abler hoped to plead before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council; the judges often took their vacations in England; all saw to it that Haliburton or another London-dwelling Bluenose put up their names at Brooks’s, the Carlton, or the Travellers’. But few, lawyer or businessman, ascended the St Lawrence to Montreal, or penetrated to Upper Canada in search of profit or pleasure. The great world, the place of emulation and eminence, was in London.

Halifax, however, was the capital, founded and maintained as an imperial fortress, to which all the rest of the province was outport or hinterland. In the outports from Lunenburg around to Windsor, eastward to Sydney and Antigonish, and in the valleys and flatlands of the peninsula, lived a great diversity of people. In 1861 they were to number over 300,000 souls.8 A few Acadians remained, survivors of the expulsion, or exiles returned to an altered homeland. In the Annapolis Valley lived the descendants of their supplanters, the New England Yankees, Congregationalists and Baptists, the backbone of Joseph Howe’s Reformer following. Down around Yarmouth and Shelburne the Yankee strain mingled with the later American infusion of the Loyalists. On the south coast American and British Bluenoses intermixed, and in Lunenburg the still German-speaking descendants of the German colonists of 1750 continued to follow a distinctive way of life. At the head of Fundy from Windsor to Truro the Yankee, the Loyalist, and the British mingled. But from Cape Breton down far into the peninsula there was moving a tide of Irish and Scottish immigration, dispossessed crofters, evicted sub-tenants, fleeing from lands in Connemarra and the Isles so barren as to make Nova Scotia seem a land of bounty. The Irish were for the most part Roman Catholic, as were many of the Scots. Thus a Celtic and a Catholic element, unsettling and pervasive, was seeping through the ancient province, upsetting its Yankee ways, challenging its British stolidity, making it a Nova Scotia indeed. Every phase of life, from church and school to civil rights and parliamentary government, had been touched, tinctured, and transformed by the coming of the Celtic peasantry. This social and political raw material was being slowly and turbulently assimilated by the schools and the political parties, those schools of practical affairs, and as it was assimilated, was altering the crucible in which it was itself transformed. Nova Scotia had early allowed political rights to Roman Catholics; now its school system was still being reshaped from the New England township model to an informal separate-school system.

In such an alchemy was to be found the outcome of the responsible government for which Howe and Huntington had fought and which Harvey and Grey had established. The unspoken conventions of Westminster, the usage of the most aristocratic assembly since the Venetian Council of Four Hundred, had resulted in one of the most turbulent, elemental, and fierce of democracies. Howe and W. J. Johnston might allude in the Assembly to the example of Sidney and the principles of Burke; the parochial and sectarian constituencies they addressed from the hustings ignored their allusions and pressed for local works, for separate schools, or for the Bible in the schools, and always expected and always got the current price of a vote. A Nova Scotian party had to be practical, of infinite variety, heavy with promise and light as to principle, if it were to see its candidates elected in the Assembly. It was at best a loose assemblage of jealous interests seeking the support of even more jealous “independents.” The executive council formed from such a party was itself a combination of regional, racial, and sectarian interests and persons, the raw diversities of the province finally brought to a unity – fragile and precarious – by the solidarity of the cabinet. Only the personal capacity and political skill of a few men, Howe in his shabby greatness, Johnston in his rocklike integrity, Charles Tupper, swarthy, virile, taurine, the young political physician who had defeated Howe in Cumberland in 1855 – only men such as these gave the province the means to transcend the local and group loyalties and achieve the status of a political community.

Nova Scotia, largely maritime as a peninsula and an island, shared the territory of former Acadia with the largely continental colony of New Brunswick. New Brunswick was a river valley, the valley of the St John, and two sea coasts, the north shore of the Bay of Fundy and the North Shore on the Gulf of St Lawrence. The St John Valley and the river valleys of the North Shore, the Miramichi and the Restigouche, had been dominated since 1808 by the timber trade. The growth of a prosperous agriculture was hampered partly by the lack of fertile soil, but much more by the habits imposed on farmers by the distraction of ready cash for wages and of life in the lumber camps. But the heavy annual cutting for the squared timber trade and the shipyards, the cutting for the new sawmills the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 had called into being in New Brunswick as in Upper Canada, the fires – of which the holocaust of 1825 on the Miramichi had been the chief – had reduced the vast pine forests of the province and started the decline of its principal industry. Exports, like that of gypsum as a fertilizer for the acid farmlands of New England and ships for the British and American marines, by no means took its place. New Brunswick, like Nova Scotia, had to rely more on its fisheries, its farming, its shipbuilding, and less on the great staple which had made the colony a maritime Canada living on the riches of the continental mainland rather than on the precarious returns of the sea.

Yet the effects of the long domination of the economic and social life of the province by the timber trade, not yet ended, remained deeply impressed on the character of New Brunswick. Its farming was slovenly; its habits of industry erratic; its pace leisurely, whether that of the genteel leisure of a Saint John merchant or a Fredericton bureaucrat, or that of the cheerful poverty of a lumberer-farmer on the St John or Restigouche. And the want of a prosperous diversity of enterprise stood revealed not only in a general indigence, but in numbers of people. In 1861 the population of New Brunswick was to be only 252,047 persons,9 in which small number was comprised a range from dignified wealth to simple poverty, from those of a Saint John shipping or lumber magnate to an Acadian squatter in a lonely clearing on the Madawaska.

It also comprised a variety of peoples almost equal to that of Nova Scotia. Along the St John Valley to Woodstock above Fredericton, on the cleared farms and in elm-treed villages with their clapboard New England houses, dwelt the descendants of the early New England settlers and of the Loyalists. Along the North Shore from Shediac to the Miramichi, in the isolation of the forest and unnavigable waters, lived the Acadian French, descendants of survivors of the expulsion and of exiles returned to the hidden recesses of Acadia. Here were the bulk of the 69,000 French of the three provinces other than Newfoundland;10 and these secret people, living apart in isolation and neglect, were preparing the return of Acadians to the forefront of life in their ancestral lands. Many of them lived also on the Matapedia and the Restigouche on the North Shore, where they bordered on the Irish whose fathers had come in the returning timber ships to the rivers and lumber shanties of the North Shore.

These immigrants from Ireland had taken up land, and begun the cultivation of the potato, thereby starting the most profitable branch of New Brunswick agriculture. Potatoes were, like gypsum and lumber, one of the characteristic New Brunswick exports, particularly to New England, and a reminder of the Irish ancestry of the third group of its people. There were, of course, Scots as well as Irish in the province, but Lowland and Presbyterian Scots rather than Highland and Catholic. They had been drawn to the province in the first instance as timber factors and workers. They thus became rivals of the Yankees and the Loyalists, but showed the Scots capacity to disperse and merge into their environment. They added tone and texture, but hardly a group, to New Brunswick society.

Here also the development of public education in a democratic society of three national groups, and divided among Protestant, Anglican, and Roman Catholic, was producing pressure for a system of state-supported “separate” schools. But here also, more than elsewhere, the politically fragmenting, isolated or “one-idea” reform had appeared from across the border. The Maine Law of 1850, the first enactment of prohibition in North America, had led to a movement for prohibition in New Brunswick. A suave, able, handsome young politician, Samuel Leonard Tilley, had espoused the cause, and on the strength of it and of his temperance societies was becoming a politician widely known and the possessor of what was, in its operation, an efficient political organization. He introduced and, in effect, carried a prohibition law in 1855. Tilley was also a member of the government defeated in 1856, a defeat followed by the repeal of the New Brunswick prohibition law by the fury of a public that had discovered the law was to be enforced.11 He, however, returned to power in June 1857, after a general election in which his opponents were defeated, as provincial secretary in the ministry of that shifty politician, the Honourable Charles Fisher.12 Tilley’s rise was also the rise of the “Smashers,” a new political formation of democratic and liberal aspect, who combined to destroy the old order of traditional and genteel politics in New Brunswick and prepare the way for some new connection to replace the old imperial one in fact destroyed in 1846. The principal New Brunswick architect of Confederation had had a severe lesson in the art of the possible, but had laid a basis for popular support that was to help carry New Brunswick into union.

Prohibition was perhaps a continental influence, befitting the semi-continental character of New Brunswick. Across the Northumberland Strait in Prince Edward Island the insularity and maritime character of the Atlantic provinces flourished unmodified. The Island was, it was true, a fertile slice of land of a midcontinental richness, strange amid the barren rock and forest of so much of the Atlantic provinces. Farming was its chief, almost its only, industry and it lived by its agricultural exports to the other provinces and to New England – potatoes, cereals, and livestock – so much so that American fishermen dominated the island’s fisheries.13 But if a farmer’s delight, it was none the less an island isolated by waters often stormy, and even more by the grinding ice of the long and severe winters of the Gulf, Hence the Islanders possessed an insularity exceeding even that of Newfoundlanders, for their island not only isolated them, it sustained them in comfort and bred in them the complacency of the self-sufficient.

This separatist character was sustained, as in all the provinces, by a population of an unexpected diversity and subtlety of combination. In 1861 the island’s 80,857 people14 consisted of Acadian French, descendants of refugees from the expulsion, English-speaking Islanders, descended from pre-revolutionary settlers and Loyalists, and of Scottish and Irish settlers who had come in after 1800, some brought by generous landlords like Lord Selkirk in 1803, others by the timber ships en route to the North Shore of New Brunswick. The four groups of French, American-English, Scots, and Irish were divided by religion into Protestants and Roman Catholics, with the resultant struggle for religious public schools, as the democracy unleashed by the grant of responsible government sought to develop a public system of education. In 1858 the ministry was to fall in a general election, mainly on the issue, introduced from Nova Scotia, of “the Bible in the schools,” a demand made by the Presbyterians.15 Once more parliamentary institutions had imposed on them the strain of giving unity to a society deeply divided by cultural and political traditions, and by religious denomination.

Such, in broad and general terms, were the social and political conditions under which self-government proceeded in the Atlantic provinces. A fierce parochial democracy gave rein to old national and sectarian animosities, causing strife in the first instance, forcing toleration in the long run, but in this the first generation of responsible government made even intra-provincial common action difficult and slight. Yet, although these regional and religious divisions worked, there were thoughts of Atlantic union stirring. A reunion of old Acadia, or Nova Scotia, partly achieved by the reunion of Cape Breton with the peninsula in 1820, was natural enough. And Prince Edward Island had once been subordinate to Nova Scotia in civil as well as military matters. But there were thoughts of a union more extensive than a reconstitution of Acadia would be.16 Even Newfoundland, isolated as it was, could think of united colonial action. In 1857 it sent a delegation to the other Atlantic colonies to seek support for its protest against the proposed Anglo-French convention to regulate the fisheries off the French Shore.17 What was stirring was the concept of a union of the Atlantic provinces with the other British-American provinces in a continental union. Howe had expressed it in his facile eloquence in 1852, Johnston in his firm severity in 1854. Their grandiose vision of British-American union was a response to the possibilities of railway construction, so evident in the 1850’s. These possibilities promised to give the Atlantic provinces access to a continental hinterland that might add to, or replace, their natural commerce on the seas. The Johnston government was indeed to approve the concept of such a union in the very year of 1857, and their delegation to London was to discuss it unofficially there.

Little discussed in public or private as yet was the thought of a union of the Atlantic provinces themselves, at least of the three other than Newfoundland. This was the thought chiefly of governors like Head, Lieutenant-Governor of New Brunswick until 1854, and of his successor, Manners-Sutton. The Earl of Mulgrave, Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia, joined them when appointed in 1858.18 All saw a union as a means of correcting the pettiness, the frictions, and the corruption of the politics of self-government based on county democracies and conducted in petty legislatures of thirty to forty members. When divided into government supporters and opposition by narrow margins, as was usually the case, the changing of a few “independent” votes could upset ministries and force elections. A larger province and a larger assembly would, these gubernatorial civil servants of English background hoped, give colonial politics a stability and an integrity obviously and notoriously lacking. In this hope of Maritime union they were joined by some men of the old school, and by both Liberal and Conservative politicians of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, such as Tilley and Johnston.

The thoughts of union were, however, occasioned and embodied in rare public speeches or in unpublished dispatches to the Colonial Office. The obstacles to a union of the Atlantic provinces were practical, evident, and persistent – some natural, some institutional. The natural ones were the geographic factors of dispersion of settlement by the sea, the mountains, the marshes, and the forests. There were few roads and almost no railways in the provinces – none at all in Newfoundland. Travel by sea could be made dangerous by fog and an unlighted rocky coast in summer, and was hazardous by sail or even steam in winter; in the Gulf of St Lawrence it was stopped by the winter’s ice. Hence the local spirit of the county democracies was the result of a considerable isolation from other communities; among the provinces the isolation was even more pronounced. To assemble a common legislature in the winter would have been a major and sometimes a dangerous undertaking in the late winter months, the normal time of assembly. Administration would have ceased to be provincial and become the work of local justices and local assemblymen.

The institutional obstacles were even more obstructive. The existing assemblies were stiff-necked vested interests, the members of which had no desire to merge themselves in a larger, however abler and more honest, assembly. A single provincial government, moreover, would have required a much better system of local government than any one of the existing provinces had. Newfoundland really had none, outside of St John’s. The old county system of England gave little in the way of local government to the other provinces; they were judicial units and political constituencies, not local governments. There were no county councils, no parish councils, no wardens or reeves as in Canada, only grand juries and justices of the peace. The county representatives of the provincial assemblies had kept the voting and spending of money for public works and education in their own hands, and with them the consequent patronage. Until the creation of a democratic and efficient system of local government had developed further in all the provinces – Newfoundland with its strange society excepted – a union of the provinces would involve far more than at first sight appeared, and would be viewed with distaste by every practical politician from the St Croix to Cape North.

Perhaps, however, the greatest obstacle to a union of the Atlantic provinces lay in the fact that they still felt themselves sufficiently united by the broad and flexible framework of the British Empire. In that union of common allegiance, common institutions, common defence, their local democracies could thrive in perfect liberty and slowly work from diversity to unity, from prejudice to tolerance. Their citizens did not feel that they belonged to petty communities, but rather to one of the freest, strongest, and most progressive of the world’s societies. There was no part of the provinces so remote that the justice derived from Westminster was not available, there was no part of the Empire, however distant or exotic, in which a native of the province might not serve or settle. In 1857, when the news came that Delhi had been stormed and recaptured from the mutineers, there came also news of the Nova Scotian dead and wounded – as also of the English and French Canadian. In 1859 some Prince Edward Islanders, weary of the land question, sailed in their own brig for New Zealand; the same solution was employed by some Nova Scotians. The provinces, then, were not without unity; it was the unity of the imperial connection, a unity and a connection which threw the world open to them.

Nor was it a matter of a common allegiance only. The Colonial Office and the War Office still governed in the Atlantic provinces to a much larger degree than in more populous, continental, and indefensible Canada. The governors were more active members of government and less constitutional monarchs than the governors of Canada.20 This difference was partly a matter of size, and partly a matter of the role the maritime colonies played in the strategy and diplomacy of the Empire. The French Shore in Newfoundland and Halifax in Nova Scotia still played their parts in the manning and servicing of French and British sea-power in the North Atlantic and the Channel which had no counterparts in Canada. And the devolution of imperial services, such as lighthouses, lunatic asylums, or Indian affairs, had not proceeded as fast or as far as in Canada.21

In Newfoundland, for example, the great fishery, although for years wholly island-based and no longer carried on by West Country ships provisioned and manned in southern Ireland, was still financed and managed by English capital and by merchants or factors drawn from the English West Country. Even when long settled in St John’s, they still kept up transatlantic ties and even a transatlantic existence. If the newly discovered ores were to be mined and the island’s economy varied, if Newfoundland were to exploit its position on the new lines of communication by steamship and submarine telegraph, it would be with English capital and English management.22 And British consular services on the Mediterranean and British rule in the British West Indies kept open the markets of those regions for the salt cod of the fishery.

The island was equally dependent on the Empire for defence. The rights in the French Shore, the French possession of the islands of St Pierre and Miquelon off the south coast, meant that Newfoundland was still, as in the two preceding centuries, an object of policy to the French marine. For the fishery was a nursery of seamen for France, if not for England. Hence the summer cruise in Newfoundland waters of the North American squadron, and the interest shown in 1858 in the visit of a French naval squadron to St Pierre and Miquelon.23 The visionary Bonapartist adventurer on the throne of the Second Empire was quite capable of dreaming, as the visit of the frigate La Capricieuse to Quebec in 1855 had hinted, of attempting to revive French influence in the North Atlantic. Hence also the maintenance of the Newfoundland Companies, local men in imperial pay, for the manning of the batteries covering St John’s Harbour, and for the defence of the town against a landing. And, as the riots of 1861 were to show, imperial troops were needed on occasion to keep order in a colony too divided to keep the peace by its own means.24 A militia the government thought impossible for want of revenue.25

Police was a service, it is to be noted, that the imperial government was most reluctant to maintain in a colony; internal order was clearly understood to be a local responsibility. There were, however, few other imperial services in Newfoundland. The extinction of the Beothuks in the eighteenth century had left Newfoundland without Indians, save for a few Micmacs who had crossed Cabot Strait. There was no provision for the insane. Only the few lighthouses, particularly that on Cape Race, were a matter of concern to the Colonial Office, and it was seeking to devolve responsibility for this marine service on the colonies – an attempt of doubtful justice, as the lighthouses were as useful to British shipping as to that of the Atlantic provinces. Their provision should have been left an imperial, as it was to become a federal, responsibility.

In Nova Scotia it was defence that was the prime imperial tie. The naval base was a major imperial strongpoint; the money spent, the prestige acquired, the social affinities formed, made Halifax a city as well as an imperial garrison. The imperial government therefore had a special eye to the province which was not only an imperial responsibility but also a source of imperial strength. It was more essential for the Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia to keep the home government informed of the military resources of the colonies and of the movements of possible enemies than it was for his colleagues in the other provinces to do so. It was in Nova Scotia, of all the Atlantic provinces, that the volunteer movement, which began during the Crimean War and was to be accelerated by the French war scare of 1859, first developed and flourished most.26 While Nova Scotia looked primarily to the navy for defence, yet it was in the volunteer movement of 1859 that there began those units some of which were to last and become part of the militia of the Dominion of Canada.27

The other ties between Nova Scotia and the Empire were as strong, if less tangible. Despite free trade and the Reciprocity Treaty, Nova Scotians still looked to England for markets for their exports, especially for the export of ships, and still more for capital and expert advice in finance and industry. Particularly important to Nova Scotia from 1852 was the possibility of an imperial guarantee of a loan to build the Intercolonial Railway. That enterprise would pull the small publicly built and operated provincial lines out of the financial morass into which they were sinking and give them traffic from beyond the boundaries of the province. So important was this matter that in 1857 the Johnston government sent a delegation to England, consisting of A. G. Archibald, Sir Samuel Cunard, and Johnston himself, to obtain the surrender of Crown lands and minerals to the colony, and to obtain imperial support for the Intercolonial Railway. Because of Johnston’s own belief in union, they were also to raise the question of British-American union.28 The mineral lands were obtained, but the imperial government, engrossed with the Indian Mutiny, gave the Nova Scotians no more encouragement than they gave Macdonald.

Other government services still controlled from Whitehall were few. The currency was still Halifax currency, but was to be made a decimal currency in 1860 to handle the growing trade with New England,29 a measure the other provinces took one by one under the Reciprocity Treaty. The post office was to be transferred to the province in 1859;30 Indian affairs also were still imperial, as was the provision for lighthouses. But these lingering remnants of imperial government would not long continue, once the province acquired revenues sufficient to assume them.

The same story is to be told of New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. Defence was not important on the New Brunswick frontier, and it was an area the War Office chose to man in time of danger rather than to garrison. In the Island any troops stationed there were likely to be valued for their expenditures and used for police, as in Newfoundland, especially when the tenantry threatened to riot against the still-unextinguished evil of absentee landlords. Neither province had kept up a militia; both were extremely reluctant to revive military service, even by means of a volunteer movement. As the governor of New Brunswick explained, they regarded freedom from taxation for defence “as one of the principal, if not the principal, compensations for their subordination as a colonial community to the authority (especially in questions of an international character) of the Imperial Government and the Imperial Legislature.”31 The lunatic asylum of New Brunswick and its lazaretto remained under Colonial Office supervision. Both looked to the metropolis for loans and advice; New Brunswick, like Nova Scotia, hoped for an imperial guarantee for the Intercolonial Railway, and Prince Edward Island tried hard to obtain a similar guarantee provided by the Land Purchase Act of 1857.32 And in both provinces the governor sought advice from the Colonial Office on how to keep responsible government functioning in communities so small and unsophisticated.33

The final tie, and the principal cause of the provinces’ feeling of security in their geographical isolation and parochial political communities, was the institutional pattern that held them in the Empire. The Common Law and jury trial; the county and the justice of the peace; the elections at the hustings and the meeting of governor, councillors, and representatives as colonial King, Lords, and Commons; the freedom of the press, of assembly, and of speech; a vigorous political freedom and an ultimate tolerance – these created an institutional pattern which, if no more British than American, was by the fact of allegiance British-orientated. The result was a conscious imperial patriotism which subsumed all the local loyalties and gave the people of the Atlantic provinces a political psychology so secure that they felt little need for union or reunion as the Canadians did.

All the same, the British-orientated institutional pattern was traversed by a cultural pattern derived from New England. Since 1714 the Acadian lands had been assimilated to the folk culture of New England: the township, the township school, the Congregational Church, then the Baptist, the steady skepticism in all practical affairs, the persistent commercial sense, all these traits of the Yankee culture and personality, however modified or veiled, pervaded the thought and speech, the habits and the assumptions, of the old American stock in the Atlantic provinces other than Newfoundland. To them New England was a second home in a way old England was to very few. Old England was the metropolis, the seat of the empire and the source of honour, but New England was the land of kindred habits and familiar thought, the same native dignity and the same level-eyed equality. In this cultural pattern the Atlantic provinces other than Newfoundland found a second framework of unity; in it they might all find political union, should need arise and no alternative be acceptable.

This Yankee culture, however, was challenged by three rising elements in the provinces. One, as yet unnoticed, was the slow resurgence of the Acadians. Another was the growth of the Scottish immigrant population in Nova Scotia. These folk had a native culture as hardy as the Yankee, and what the American Nova Scotian had not, a conscious determination to maintain it. Both the Presbyterian and the Roman Catholic Scot had begun the academies and colleges which were to preserve his Scottish intellectual inheritance by the wedding of poverty with intellect. The third element was that of the Irish Roman Catholic, already pressing for the creation of separate schools and defying the Yankee concept of a uniformity of education to produce a consensus of opinion. All three, when the time should come, would make their defiance of the Yankee cultural pattern a factor in the politics of the Atlantic provinces, the Acadians in self-defence, the Scots to ensure their predominance in Nova Scotia, the Irish to consolidate in the British provinces an actual liberty superior to that accorded their Catholic brethren in the United States.

Despite their lack of wealth and population the Atlantic provinces, then, had cause to rejoice in their local liberties and loyalties, and to feel themselves secure within the imperial art of Britain and the friendly neighbourhood of the “Boston states.” Yet each had a problem, or problems, of weight that neither the imperial connection nor the friendship of the United States were to solve. In each instance, the failure of imperial administration or American influence to solve these matters was a cause of the Atlantic provinces, except Newfoundland, entering the union of British America by 1873. Here then were the finally decisive causes of British-American union in the Atlantic provinces.

Newfoundland, it is true, was almost to enter union, and then to draw back. It indeed had a problem that the imperial government was not to solve in the nineteenth century, that of the French Shore. But the union of British America, when it came, was in no position even to take up that vexed question; the Dominion of Canada had no international being until well into the twentieth century. Yet the French Shore was a problem which, had it been soluble by British-American union, might perhaps have carried the island into Confederation. When by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 France had acknowledged British sovereignty in Newfoundland, it had been granted limited fishing rights along and in a “French Shore,” defined only as extending from one designated point to another on the north and west coasts of the island, points which were shifted in the treaty of peace in 1783.34 The treaties gave French nationals no other rights on the Shore than the exercise of the traditional fishery, the right to catch bait, cut wood, take on water, and dry fish. By the middle of the nineteenth century, however, two trends had changed the situation. The Newfoundlanders were beginning to settle on the west coast in the French Shore, and to enter the fishery there; the French were replying by forming fishing-stations on the Shore,35 which they often employed Newfoundlanders to tend in the winter season. In circumstances where rights were so undefined, clashes occurred, and the Newfoundlanders became increasingly impatient with an imperial treaty that seemed to allow a violation by the French of the obvious rights of settlement and fishing along all the shores of the island, including the area where, the colonists held, the French had an equal, but not an exclusive, right to pursue the fishery.

The imperial government had in fact taken up the matter with the French as early as 1852, and pursued it in the cordial atmosphere obtaining in the relations of the recent allies of the Crimean War. This it did, despite protests from the island in which public opinion feared additional concessions might be made to the French. The outcome was the conclusion of a convention late in 1856, which was to be submitted to parliament for ratification in the session of 1857. Labouchere first sent a copy of the convention to Governor Darling in order to obtain the opinion of the Newfoundland ministry. Darling, however, failed to make the opposition of his government known. When his dispatch and the terms of the convention were made public in St John’s, an indignant outburst of protest followed. The difficulty was that to define the undoubted but vague French rights was to seem to increase them. The opposition took up the protest in the assembly and the legislative council and were joined by the supporters of the ministry. Darling was overwhelmed and gave way before the pressure. The result was a set of resolutions demanding that no convention should be ratified by the imperial parliament until approved by the assembly and people of Newfoundland. At the same time a delegation was dispatched to the other Atlantic provinces to seek support in opposing the convention.

Three hours after the terms of the convention were laid before it, the Assembly resolved that its terms were “subversive of the just rights and destructive to the interests of the people of this Colony, the concession without any real equivalent, of almost unlimited fishing privileges.”36 The resolution went on to express the Assembly’s “unanimous and unalterable determination never to give their assent to a measure so unjust.” It might well so speak: outside the Colonial Building, a great crowd milled and in the harbour most of the ships flew their flags “UNION DOWN.”37 And there was excited talk, Darling reported, of annexation to the United States.38 When the news reached him, Labouchere, in an important dispatch, the “Magna Carta” of Newfoundland, hastened to agree that the government of Newfoundland would be consulted before a convention was ratified. He wrote that “the consent of the community of Newfoundland is regarded by her Majesty’s government as the essential preliminary to any modification of their territorial or maritime rights,” and that the constitutional way of securing assent was submission of a measure to the colonial legislature, as had been done with the Reciprocity Treaty.39 The rights of self-government were thus generously acknowledged, a precedent for the ratification of the terms of British-American union.

The result, however, was failure to ratify the convention of 1857, which was wholly unacceptable to Newfoundland. Succeeding attempts to modify the régime on the French Shore were to fail and the island thus continued to be oppressed by a grievance the imperial government was incapable of removing. It can be understood, then, why the Newfoundlander could quote with approval from the Quebec Colonist: “The Newfoundland Fisheries – Union of the Colonies. If the British Provinces were united into a grand confederation, their rights would be better respected and their importance valued not only by the mother country but by foreigners…. We trust this treaty affair will impress upon our fellow colonists as well as ourselves the necessity of a Federal Union of the provinces at once. If it does, good may come out of what was considered a great evil.”40 To some degree, the French Shore was a factor predisposing Newfoundlanders toward union, in order that a larger body of colonial sentiment might bring its weight to bear on Whitehall.

After Newfoundland, the province with the problem most in need of solution by the imperial government was Prince Edward Island. There the land question dominated all politics, and made the island the Ireland of British America. The land grants of 1767 to absentee landlords had left the island a heritage of economic hardship and still more of social bitterness that had to be removed if the province were to know peace. A Land Purchase Act of 1853 had marked the adoption of the state purchase from the landlord for resale to the tenant, but the island lacked the means to begin to buy out the landlords.41 Its scanty revenues were, in fact, over half committed to the costs of the public-school system.42 It was this defect that the Act of 1857, mentioned above, sought to remedy. If an imperial guarantee were made, it would be possible to raise a fund at a low rate of interest and, when terms of sale had been agreed upon, begin to purchase and transfer the lands.

A guarantee, however, was not forthcoming. The Colonial Secretary, Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, admitted that the making of the original grant had resulted in evil, but in face of the island’s lack of revenue, he did not see how he could persuade the Treasury, oppressed by the cost of the Crimean War and grimly determined to continue the reduction in expenditures on the colonies, to agree to reverse the trend and guarantee such a loan.43 He therefore refused the request, and the island was left to try to deal with the problem of purchase by itself. The purchase of the Selkirk estate of 62,000 acres and other lands in 186044 marked the beginning of the end of the proprietary system in the island, but the foretaste only underlined the difficulty of completing an undertaking so much beyond the financial resources of the province, based as these were on custom duties only.

In more developed New Brunswick and Nova Scotia there was the common problem of railway construction, the main form of Victorian progress. Both provinces badly needed a small railway system for internal use. Although necessary, this was not extensive enough to attract sufficient private investment, and the railways had therefore to be built as public works. This proved very costly. By 1857 both had incompleted projects on their hands and a heavy increase in debt. The Nova Scotian line to Truro, the New Brunswick line from Saint John to Shediac, were a fragment of an uncompleted design, a railway line around the Bay of Fundy to connect both provinces with the continent. To complete the system and to carry the debt, a connection with some more extensive system of railways and a more abundant source of credit were needed.45 In both provinces an election was approaching, and nothing could be more helpful to a colonial government of those days than the prospect of railway construction. A connection westward with New England railways or a connection northward with the Grand Trunk Railway would, moreover, serve to rescue the provinces and their credit. It would also link the provinces and their ports with the continental hinterland, a matter some businessmen were beginning to think important. The old project of an intercolonial railway was the most attractive means to realize these aims, and its strategic value would help secure an imperial guarantee for the loan necessary to its construction. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick therefore joined with Canada in the approach to the Colonial Office in 1857 for a guarantee, but this renewal of the colonial effort to obtain imperial aid for the intercolonial railway project was turned down on financial grounds.46 With the Crimean War just over and the Indian Mutiny still not crushed, no mid-Victorian Chancellor of the Exchequer would risk the guarantee of a colonial loan. Perhaps more important was the agreement of all Victorian politicians that self-governing colonies ought to be self-sustaining, for their own good as well as for the good of the British tax-payer.

In this matter of the Intercolonial, the needs of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick approached those of Canada, which required the Intercolonial as an outlet for the Grand Trunk, as a strategic safeguard when ice closed the St Lawrence in winter, and above all, as a sleeping check on American rates on the line from Montreal to Portland and to a withdrawal of the bonding privileges on Canadian goods moving over that and other American lines. As “a Canadian gentleman” wrote to Lytton, the coming of the railway had made Canadian business dependent on American outlets from December to June, as the more primitive commerce of earlier times had not been. The withdrawal of the American bonding privileges would therefore be a commercial disaster and could be a political threat because of “the absolute state of dependence in which we are on a foreign Nation’s policy.” An intercolonial railway would not end the use of American ports, but it would be a commercial as well as a military reinsurance.47

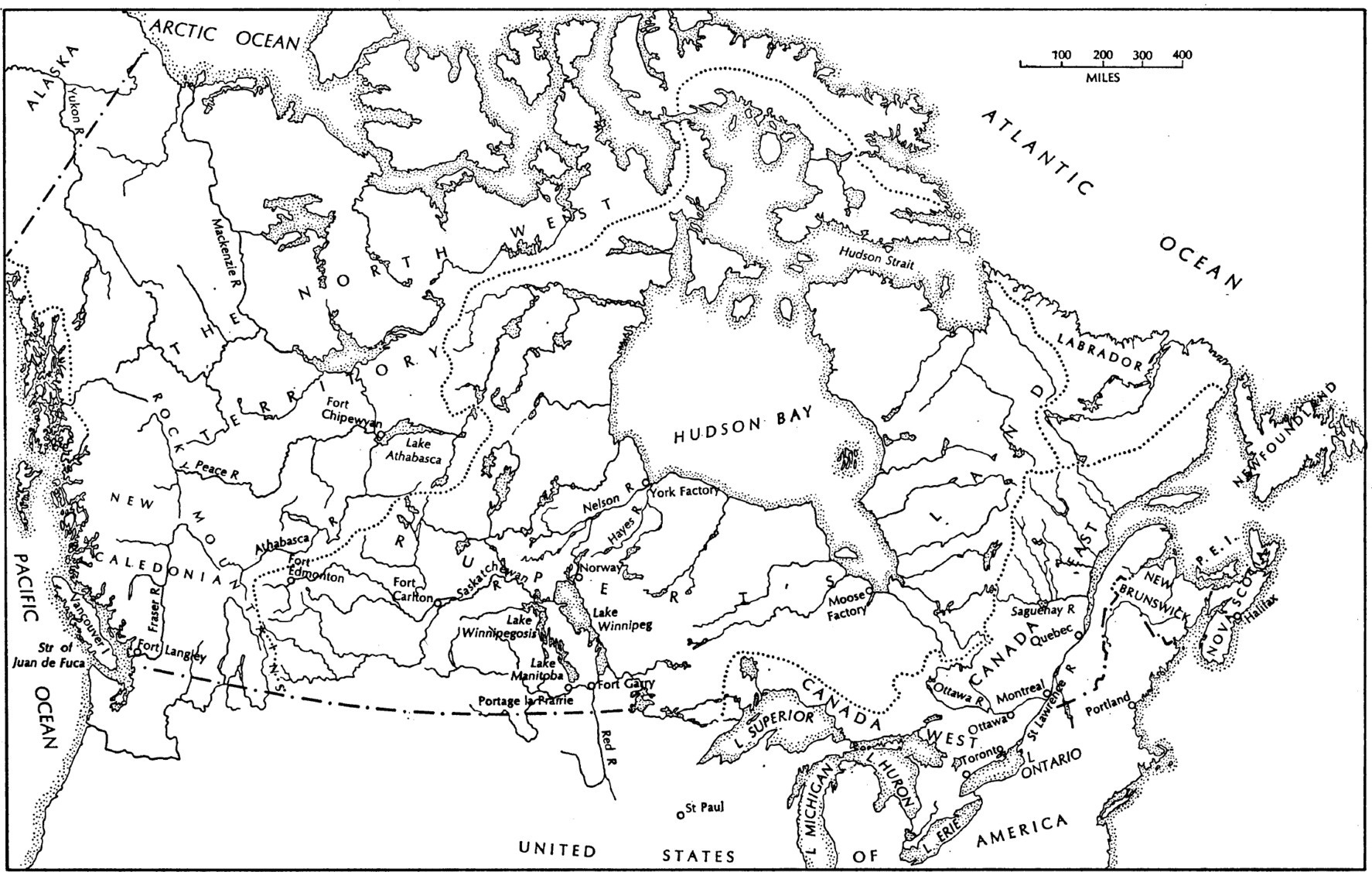

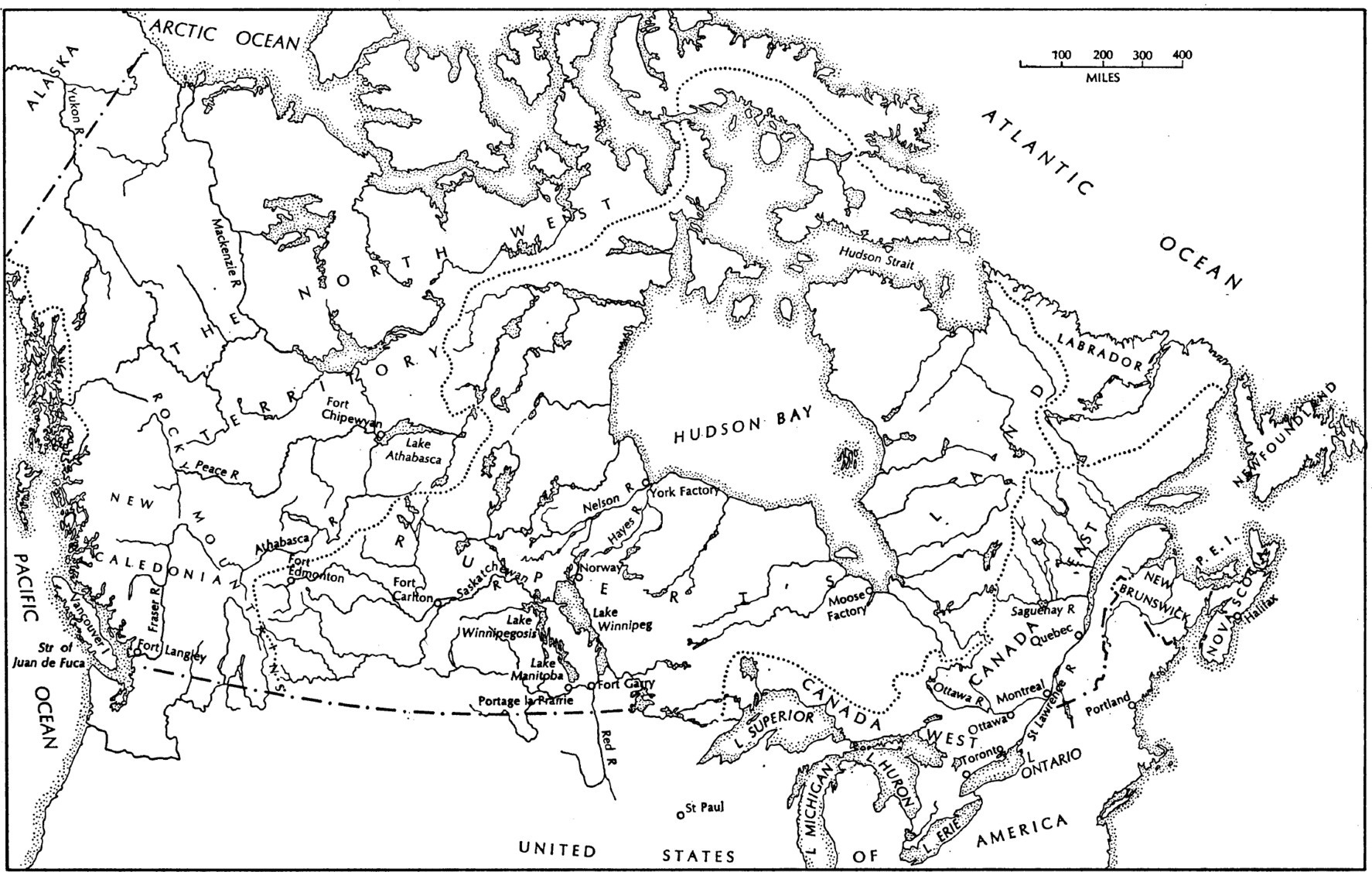

The Vast Emptiness of British North America, 1857

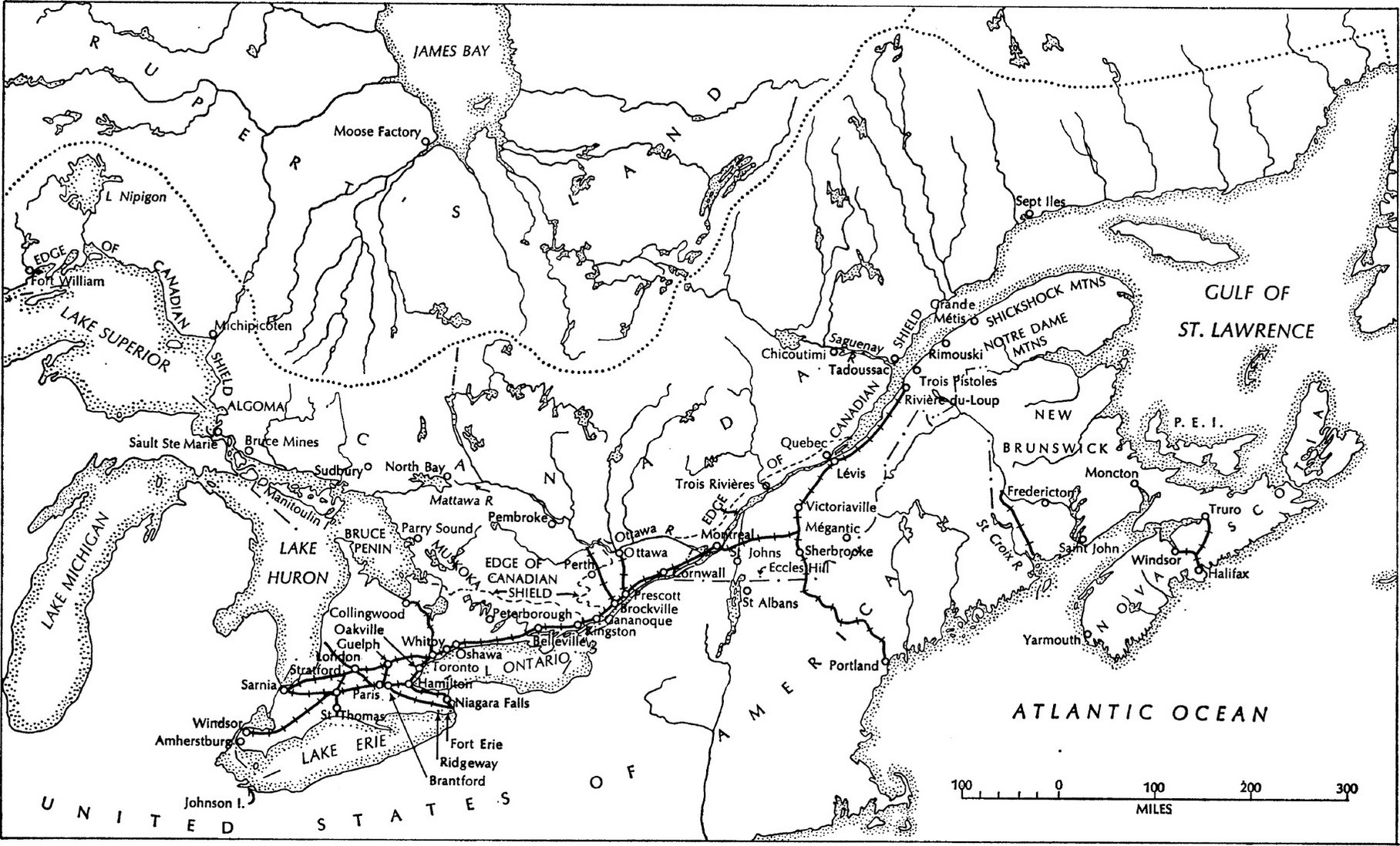

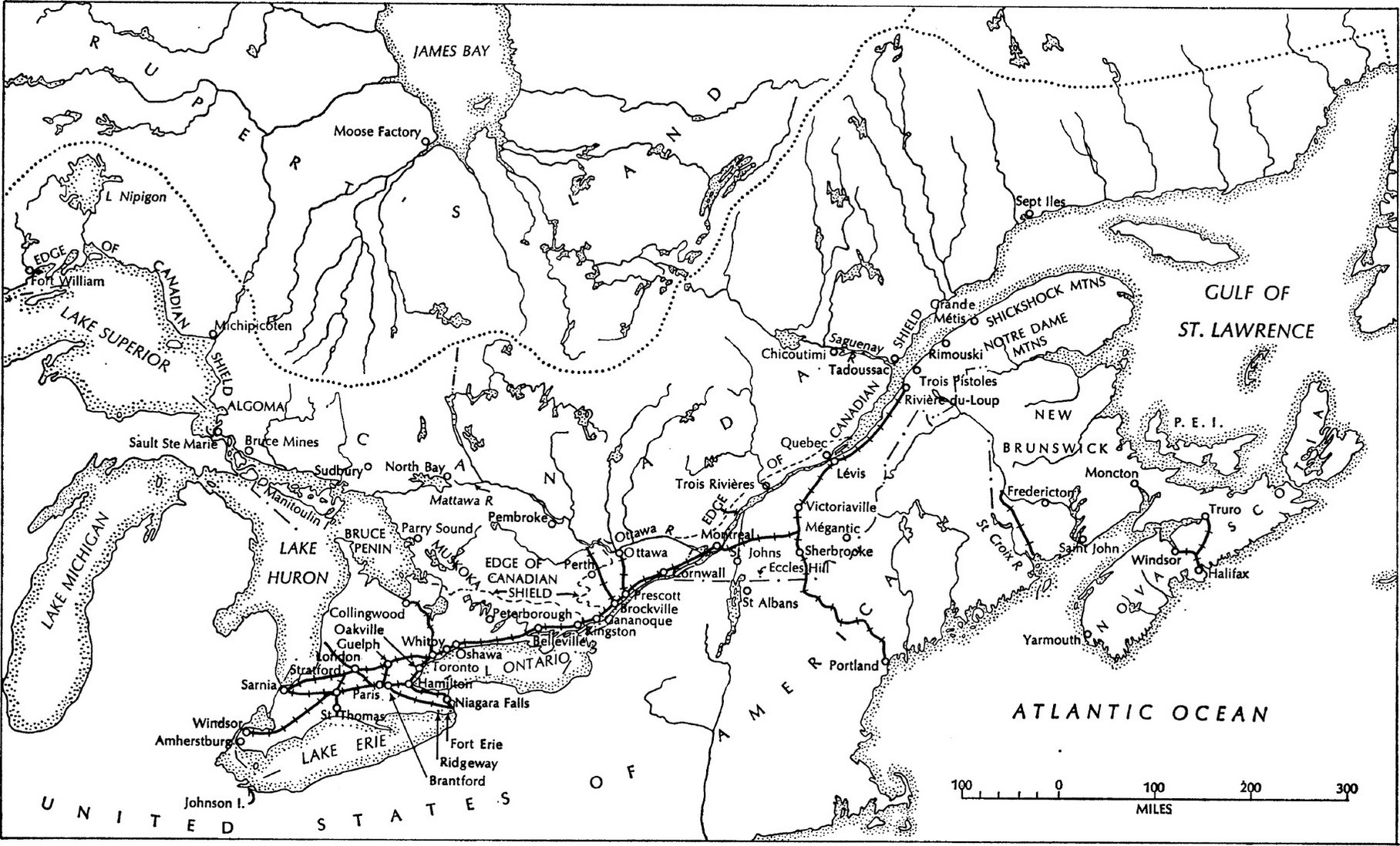

The Settled Provinces of British North America, circa 1860

To the two Atlantic provinces, then, the Intercolonial was an electoral expedient as much as a route connecting them with the continent; to Canada it was a guarantee of economic and even political independence. The need of the provinces for an imperial guarantee to ease the financing of their railways and improve their prospects of election, therefore, put them in touch with the dynamic expansion of Canada, a Canada which might attempt the resolution of problems that a liberal Victorian empire was disposed to evade. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick therefore sent delegates to London in 1858, to join the Canadians in pressing, not the union of the provinces, but the building of the Intercolonial.48 Most politicians of the Maritimes thought, as did Howe, for instance, and Lytton, that railway and commercial connections could well precede political union; the Empire would suffice for political framework. The governments of the Atlantic provinces were thinking mainly of a railway connection; on political union they were uncertain and undecided.

The insular and peninsular provinces, then, were beginning to feel the pull and counter-pull between their old maritime ties and those of the new continental attraction of Canada. The former were weakening, the latter strengthening. The continental would prevail over the maritime, the federal would undertake what the imperial refused or hesitated to do. But in 1857–58, the time was not yet. The Atlantic provinces returned answers of uncertain tone and purport to the Canadian proposal of August 1858, to discuss a union of British North America. In the end they waited for an imperial lead. But in this matter it had been decided in London that there would be no imperial initiative to carry forward the Canadian proposal that political union of British North America should be discussed by the British North American colonies. The Canadian initiative of 1858, bold and stirring as it seemed in Toronto, had been received in London with consternation, anger, and the final conviction that the Canadian initiative was provincial and self-seeking.