Dear Diary,

Outside the zoo, a small crowd of people gathered, and we joined them and looked up toward a brick archway. Music filled the air, and bronze animals started moving in a circle. A penguin played a drum; kangaroos played horns; an elephant played the accordion; a bear banged a tambourine; a hippo played the violin; and on top, two monkeys rang a big bell.

“Mono,” Monkey Boy said, since he’s proud of his new word.

“This is …?” Miguel asked.

“The Delacorte Clock,” Mom said. “It does this every half hour. When Matt was in a stroller and Mel was in pigtails, they adored this clock.”

“Pigtails?” Miguel asked.

I shot Mom a look that said: “Please don’t explain!” Too late. She’d already picked up her hair in two high bunches.

Sometimes she doesn’t get it! After Spring Fling, she met Justin and said, “I’ve heard a lot about you,” when it would have been much better not to say anything!!

Miguel smiled and said, “I like it. Me gusta” (May Goo Stah). I wasn’t sure if he meant the clock or the pigtails.

We left the zoo and walked south, past artists drawing flattering charcoal portraits of tourists, artists drawing insulting caricatures of tourists, people selling  shirts to tourists, and horse-drawn carriages giving rides to tourists.

shirts to tourists, and horse-drawn carriages giving rides to tourists.

Who knew New York was so STUFFED with tourists?

An old black horse made me think of Black Beauty. I looked at Mom and whispered, “Carriage ride?” She whispered, “Too expensive.” (No surprise.) So we just watched carriages clip-clop by. One had a couple in it, but they weren’t being very couple-y. The man was taking photos of the park on his side, and the woman was taking a video of the park on her side.

Next stop: the Plaza. We went up the red carpet, held on to the gold stair rail, pushed through the revolving door, and walked under the big chandelier to the Palm Court, where dressed-up people can have tea and listen to harp music. I showed Miguel the big painting of Eloise, who lived at the Plaza with Nanny; her dog, Weenie; and her turtle, Skipperdee. I love Eloise, but Miguel didn’t even know who she was. You can be famous in one country and unknown in another! Even though it was a little embarrassing, everyone had to wait for me to go to the Plaza’s bathroom, since I’d been writing when I was supposed to have gone at the zoo. (I prefer fancy bathrooms anyway!)

Next we crossed Fifth Avenue, passed the FAO Schwartz clock, and headed north. Mom and Matt were walking ahead, and Miguel and I were behind. I wanted to say something deep or romantic, but somehow I started telling him about how Cecily’s cat likes to bite the end of toilet paper rolls, then race through the apartment with tp flying behind him. I also told him about how Cheshire once licked some water—but it was sparkling water—and it made him sneeze sneeze sneeze!

My stories made Miguel laugh, and that felt good.

Mom smiled at us and said, “I hope your shoes are comfortable, Miguel, because in New York, everyone gets lots of exercise without even trying.”

At the corner of East 70th Street, we reached a mansion that used to belong to a rich guy named Frick. Mom took me once last fall. The Frick is loaded with masterpieces, but it’s small—so it’s not overwhelming like the Met. The problem? You have to be ten to be allowed in.

When Mom planned Miguel’s day, she forgot that Monkey Boy is not even eight!

“What are we going to do?” I asked.

“Have a hot dog?” Matt suggested.

Mom bought us hot dogs from a hot dog man under an umbrella. I got mine with ketchup; Miguel did too. I think he was a little surprised that we ate them standing up—Spanish lunches are often two-course (or even three-course) sit-down meals.

“Delicioso” (Day Lee See Oh So), Miguel said, and Mom offered him another one. He accepted and asked, “You know how we say ‘hot dog’?” I shook my head. “Hot puppy! ¡Perrito caliente!” (Pair E Toe Cahl E N Tay). Matt cracked up. “And you know how we say ‘children’ in slang?”

“¿Niños?” (Nee Nyose), I asked.

“Mocosos (Mo Co Sohs). It means ‘Snotty noses.’ ”

“Ewwwwwww!” Matt shouted, happy as can be.

A lady with long legs followed by a puppy with short legs scowled at Matt as though he were a problem child—which, of course, he is.

Mom looked worried. “Matt, listen carefully. Can you pretend to be ten?”

“Sí,” Matt said.

“No monkey business,” Mom added.

“But I’m a mono mono!” Matt started scratching his armpits and ooh-ooh-oohing.

“I need you to be a serious boy,” Mom said. “We’ll stay just a few minutes, but I’d hate for Miguel to miss the Frick. It has three Vermeers!” To us, she added, “I hope Matt doesn’t get ants in his pants.”

Miguel looked alarmed. “Ants?”

Mom laughed. “It’s an expression! It means: I hope he doesn’t get restless—antsy.”

Inside, she showed her membership card, and the man asked how old we were. Mom said, “Twelve, eleven, and ten.” He eyed Matt suspiciously, but Matt flashed his Angel Boy Smile, and the man waved us in.

“Behave,” Mom whispered again, and handed us Art-Phone audio guides. Miguel’s was in español (S Pon Yole).

We walked through the peaceful courtyard with its trickling fountain, then entered the big room.

“The kids sometimes play a museum game,” Mom started explaining. I nearly died because I didn’t think Mom even knew about Point Out the Naked People.

“A game?” Miguel said.

“Yes. Sometimes I ask them, ‘If you could have one painting in this room, which would you choose?’ ” Oh, phew! That museum game! “Everyone walks around, then we meet in the middle, and I say, ‘One two three,’ and we all point to our favorite.”

“Ready?” Mom said.

We walked around, then met in the middle. “All right,” Mom said. “Uno dos tres.”

We were pointing in different directions, and I said, “You go first, Mom.”

“I love the Rembrandt self-portrait.” We walked over to it.

“You’re supposed to say why,” I said.

“Because he looks kind and real and sad and wise.”

“If you could save only one painting in the whole world, would this be the one?” Matt asked.

“What would happen to the others?” Mom said.

“I don’t know. Fire? A flood? Turpentine?”

She looked pained, so Matt changed the question. “I just mean: Is this your top favorite painting of all time?”

“I think so.” Mom turned to Miguel and said, “Doesn’t Rembrandt have a wonderful face? I always say hello to him when I come here. I like to think of him as an old friend. Maybe a grandfather.”

Grandpa Rembrandt.

I looked to see if Miguel thought Mom was crazy—loca (Low Cah)—but he just smiled. Mom continued, “I like to think he’s saying, ‘And what have you been up to since you last came to see me?’ ” She laughed. “Okay, someone else’s turn. Matt, you go.”

Matt said, “Same as Mom.”

“Copycat!” I rolled my eyes. “How about you, Miguel?”

“I have picked Felipe IV” (Fay Leap Ay Qua Tro).

“Velázquez’s Philip IV,” Mom said. “Why?”

“I like seeing our king in your country.” Maybe since Mom is an art teacher, Miguel added, “And I like the gold in his cloak and the orange in his hair.”

I gave Miguel a smile and I think he winked. But maybe it was just a funny blink? I wanted to ask him, but then I realized that you can’t ask a boy if he winked at you or not.

“And you, May Lah Nee?” Miguel asked. For a second, I started picturing myself giving him a little kiss right then and there, but of course I had nowhere near enough guts. Besides, we were with my family!

“Your turn, Mel!” Matt said, which yanked me out of my daydream.

I said, “Georges de La Tour.” We walked over, and I said I liked how the candlelight was reflected in the girl’s, Mary’s, face, and how the light coming through her fingers turned them see-through, like when you shine a flashlight behind your hand. Then I noticed its title, The Education of the Virgin. I did not want Miguel to read that, so I said, “Let’s keep going!”

Mom said, “Shall we go to the Fragonard Room to see The Progress of Love?”

“No!!” I said too loudly, since that title was even worse.

Miguel said, “It is very tranquil here.”

“No Snotty Noses,” I agreed.

Right on cue, Matt bounded over, looked up and down the long hallway, and said, “Mom, you’d kill me if I ran back and forth, right?”

“Correct,” she said. “So you’d end up dead and I’d end up in jail. Don’t do it, okay?”

“Okay,” Matt said.

“Slow down and let the paintings speak to you.”

“Okay,” Matt said. Then he whispered to me, “Naked Statue Alert,” and pointed out some R-rated sculptures on the long table behind us.

Mom sighed and led us to the room with the George Washington painting.

“Can I sit down?” Matt asked, eyeing an ancient embroidered chair.

“Don’t you dare!” Mom practically shouted. “In fact, we’d better go—though I hate to rush you, Miguel.”

“I don’t mind to leave,” Miguel said. “A skyscratcher, a zoo, a hotel of luxury, a museum—I have already seen a lot of New York.”

“We’re just getting started!” Mom said, adding that rascacielos (Ra Ska Syell Ohse) is skyscraper not skyscratcher.

We were about to go when Matt pointed out the window by the coat check and shouted, “Baby ducks!” He started hollering, “Melanie!! Miguel!!” until I whispered, “Matt, you’re ten.”

“Oh yeah. I forgot.”

I looked out the window and saw a little pond with goldfish and lily pads and purple and white flowers, but no ducks.

Suddenly I saw the ducklings too, and they were adorable (Odd Or Ob Lay). “¡Pato!” (Pa Toe), I said, and pointed at one.

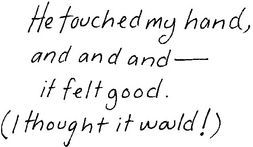

“Patitos” (Pa Tee Toes), Miguel replied. He was behind me, and he held my pointing hand in his hand and moved it from duckling to duckling, and we counted together in Spanish. There were eight or ocho (Oh Cho). I wish there had been eighty!!! I liked the way his hand felt holding mine up.

Soon other people came over to see what we were staring at. Before long, there were more people oohing and aahing at the ducklings than had been oohing and aahing at the paintings. The baby ducks followed their mom everywhere, hopping over and scooting under the lily pads.

“Vámonos” (Ba Moan Ohs), Mom said, which means “Let’s go.” She suggested we walk across Central Park, and I couldn’t object since I’d sent Miguel that Nature Girl e-mail.

Mom must have read my mind, because she said, “A little sunshine will feel good and will help Miguel get over jet lag. Once we get to the West Side, we’ll take a taxi. Deal?” I nodded.

Central Park is giant. You could walk all day and not see it all. It goes from the East Side (Fifth Avenue) to the West Side (Central Park West). And from 59th Street all the way up to 110th.

We walked and walked (well, Matt also skipped), and Miguel liked how people on horseback trotted by and how teams of kids were playing sports and how a few mothers were jogging with babies in special strollers and how we were in a park but surrounded by tall buildings. The grass in one area was freshly cut, and Matt said it smelled “green,” and I said “verde” (Bear Day), and we all talked about whether colors have smells. We passed Bethesda Terrace and got to Strawberry Fields. Miguel said, “Strawberry? Fresa?” (Fray Sa).

Mom started singing the Beatles song (she never gets embarrassed!), then pointed out the Dakota, the building where John Lennon was killed in 1980. She explained that his widow, Yoko Ono, gave a million dollars and got lots of different countries to send plants and help make a Garden of Peace.

Miguel took a photo of the black-and-white mosaic that says IMAGINE, and Mom started singing that song too. “Imagine all the people, living life in peace …”

Suddenly a squirrel dashed out and Miguel shouted, “¡Ardilla!” (R D Ya). I said that squirrels are totally common here, no big deal, but Miguel didn’t care. It was as if he had seen an endangered rhinoceros or something. He took more photos of the squirrel than he’d taken of the penguins or polar bears or monkeys or me. Combined! He even asked me to take one of him in front of a tree with a squirrel climbing up the trunk. Which I did, but I was a teeny tiny bit annoyed because I’d never been upstaged by a bushy-tailed squirrel before.

If I had pointed at the squirrel, would Miguel have taken my hand and helped me count all the squirrels in the park?

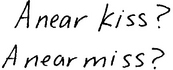

Instead of passing Tavern on the Green, we walked north to the theater where Shakespeare plays are performed outdoors in the summer. There’s a statue of Romeo and Juliet, and Juliet’s head is tilted up, and her hair is falling straight down behind her, and she’s on tiptoe, and she and Romeo are almost (but not quite) kissing. I don’t think Miguel noticed it, but I did:

Will Miguel and I kiss again?

When he was far away, I missed him soooo much. But now, even though he’s right here, it’s as if I still miss him a tiny bit. What is there between us, now that the Atlantic Ocean isn’t between us? Do girls usually think about love and stuff more than boys? And did I imagine Miguel as too good to be true? In Spain, he seemed to know about everything, but here there’s so much he doesn’t know about—like squirrels! Maybe when you’re on vacation, everything and everyone seems extra wonderful? When Miguel went to Galicia, even he described rain as magic mist, not gloppy drops. Does everything depend on how you look at it?

Back home, we showed Miguel our many mice and one little fish, Wanda. My bedroom was a mess, so I closed the door, but Matt proudly showed Miguel his room—and new bullfighter poster.

Speaking of posters, I’m glad I remembered to take down my sketches from the closet doors, a.k.a. Mom’s Art Gallery. Matt’s dorky doodles are up on display, along with postcards of real art. Mom could have been a curator. (That’s the word for a person who arranges museum shows.) Right now she has a bunch of postcards up. She calls it her “American Exhibit.”

Miguel complimented Matt’s pitiful sketches and looked at the American flags by Jasper Johns, bones by Georgia O’Keeffe, farmers with a pitchfork by Grant Wood, soup cans by Andy Warhol, and cowboys by Frederic Remington.

“Cowboys!” Miguel said. “We learned about them in school.” He looked closely at a painting by Norman Rockwell of ten happy people and an old lady serving a giant turkey. “Thanksgiving. We studied this too.”

It seemed funny to study stuff we take for granted.

“Did you learn about Harriet Tubman?” I asked, pointing to a Jacob Lawrence postcard. He shook his head. “She helped slaves escape.”

“We learned about slavery,” Miguel assured me. He pointed to some Jackson Pollock splotches. “You like?”

“Not as much as these.” I showed him a chubby baby by Mary Cassatt. He smiled and it was almost as if we were playing Mom’s museum game, just the two of us.

“And this?” He pointed to a funny photograph by William Wegman of a dressed-up dog with an umbrella.

I laughed. “My mom has weird taste—in art.” Since his dad and my mom had dated, I didn’t want him to think I thought that she had weird taste in people.

I pointed to a country scene by Grandma Moses. “She was in her seventies when she began these oil paintings.”

“Inspiring, yes?” He put his hand next to mine, and suddenly we were inspired and were showing each other the tiny trees and horses and children, our fingers almost touching.

Matt blurted out, “Miguel, come watch TV!” I wanted to bonk Matt on the head, but Miguel went toward the sofa and sat down. And conked out! Mom said it’s tiring to talk another language all day, so it was good he was taking a catnap or siesta (Sea S Tah).

His siesta is also giving me a chance to catch up in you. When too much happens and I don’t write it down, I get so full of words I feel as if I might burst.

Mom is next to me emptying the dishwasher. She just said, “Miguel is a nice young man.”

I didn’t disagree.

She probably wanted me to say more, but I stayed quiet.

P.S. Should I put the necklace Miguel gave me back on? Would that seem too obvious? Or would that be nice? Would he even notice??

Dear Diary,

I wrote another little poem.

I decided to put the necklace back on.

Fans open and close.

Maybe relationships do too.

Dear Diary,

Uncle Angel came over to pick up Miguel and to have dinner. Instead of cooking, we ordered in. Mom and Dad wished that they’d been able to cook an elaborate homemade meal, but I think Uncle Angel and Miguel got a kick out of seeing how New Yorkers sometimes make dinner.

They get out their menu file, make a decision, and make a phone call!

“Should we order in Indian?” Mom said.

“We don’t speak Indian!” Matt said, because he loves that joke.

“Or Korean?” Dad asked. “Japanese? Vietnamese?”

“How about Malaysian?” Matt said.

“¿En serio?” (N Sare E O), Miguel asked. “Are you serious?”

“It’s yummy!”

“I’ve never had Malaysian,” Uncle Angel said.

“We could do Italian or Mexican or Cuban,” Mom suggested.

“Any foods are okay,” Uncle Angel said. “Don’t molest yourself.”

“What?!” Matt said, looking shocked.

Mom corrected Uncle Angel’s English: “We say ‘Don’t trouble yourself,’ ” she said, then explained to us that No se moleste (No Say Mow Less Tay) is a common expression in Spanish.

We settled on Thai, Dad phoned in our order, and around fifteen minutes later, our doorman called to announce the delivery. Mom said, “Send him up.” Uncle Angel was amazed.

Mom was looking for money for the dinner and tip; Dad was showing Uncle Angel our apartment; Miguel and I were setting the table; and Matt’s job was to pour the milk.

Not a hard job, but obviously beyond him.

“Oh no!!!” Matt said.

Mom was in the doorway paying the delivery man.

“What’s the matter?”

“You know how you always say you’ll love me no matter what?” Matt asked.

“What did you do?”

“And you know how everyone says, ‘Don’t cry over spilt milk?’ ”

“Matthew Martin, what are you trying to pull?”

“People shouldn’t yell over spilt milk either.” Matt scrunched up his face, hoping his adorableness would save him.

Mom looked at the kitchen floor and saw that he had dropped an entire quart of sticky chocolate milk on it. If Miguel and Uncle Angel hadn’t been there, she might have exploded, but since they were, she just sighed, put down the brown bag of satay and spring rolls, and helped Matt mop up.

We lit candles, and it felt like a dinner party, even though it was take-in. I hope I’m a good host, because Miguel is a good guest—he kept refilling everyone else’s water glasses and offering seconds to the rest of us before taking more himself. In Spanish and English, everyone talked about politics and Santiago Calatrava, a famous architect from Valencia who designed our World Trade Center PATH station. Mom also described Miguel’s first full day here. She said he saw New York in a nutshell.

“Nutshell?” Miguel asked, looking handsome by candlelight.

Mom explained.

“Nooo Yorrrk een ay nutta shell!” Uncle Angel repeated, delighted.

Suddenly Miguel said, “The gift!” Uncle Angel dug into his bag and handed Mom a ceramic plate with Don Quixote on it. Mom said, “Thank you! Our whole family will enjoy this!” But I confess I wish he’d brought something just for me.

Uncle Angel smiled and got out a cigarette, which made us four M’s stop smiling and start looking at each other. Dad said, “Mind not smoking inside?”

Uncle Angel looked surprised but said, “No, no. Clearly. Ees okay.” He put away his cigarettes and got out his guidebook that explains New York. And we all planned our next tourist stop: Broadway.

P.S. I wish I had a guidebook to explain Miguel. And Cecily. And maybe Justin too.