In a finite group ![]() of order N, the order of every subgroup is a divisor of N. On the other hand there need not be a subgroup with order d for every divisor d of N. For example, in the tetrahedral group, as one can see easily, there is no subgroup of order 6. We shall now prove, however, that for every power pa of a prime dividing N there is a subgroup with the order pa.

of order N, the order of every subgroup is a divisor of N. On the other hand there need not be a subgroup with order d for every divisor d of N. For example, in the tetrahedral group, as one can see easily, there is no subgroup of order 6. We shall now prove, however, that for every power pa of a prime dividing N there is a subgroup with the order pa.

DEFINITION: A group is said to be a p-group if the order of each of its elements is a power of the prime p.

We determine the largest possible p-groups in the finite group ![]() .

.

DEFINITION: A subgroup of ![]() is said to be a Sylow p-group, if its order is equal to the greatest power of the natural prime p dividing N.

is said to be a Sylow p-group, if its order is equal to the greatest power of the natural prime p dividing N.

For example, the four group is a Sylow 2-group of the tetrahedral group. A Sylow p-group of ![]() is denoted by Sp or by

is denoted by Sp or by ![]() . The normalizer of Sp in

. The normalizer of Sp in ![]() is denoted by Np the center of Sp by Zp.

is denoted by Np the center of Sp by Zp.

THEOREM 1. For every natural prime p, every finite group contains a Sylow p-group.

Proof: If the order N of ![]() is 1, then the theorem is clear. Now let N > 1 and assume the theorem proven for groups of order smaller than N.

is 1, then the theorem is clear. Now let N > 1 and assume the theorem proven for groups of order smaller than N.

If in the center ![]() of

of ![]() there is an element a of order m.p, then the factor group

there is an element a of order m.p, then the factor group ![]() / (am) is of order

/ (am) is of order ![]() and contains by the induction assumption a Sylow p-group

and contains by the induction assumption a Sylow p-group ![]() /(am) of order pn-1, where

/(am) of order pn-1, where ![]() is not divisible by p.

is not divisible by p.

![]() is of order pn and therefore is a Sylow p-group of

is of order pn and therefore is a Sylow p-group of ![]() .

.

Now let there be no element of order divisible by p in the center ![]() of

of ![]() . If the order of

. If the order of ![]() were divisible by p, then the factor group of

were divisible by p, then the factor group of ![]() with respect to a cyclic normal subgroup (a)

with respect to a cyclic normal subgroup (a) ![]() 1 is of order divisible by p. But then by the induction hypothesis

1 is of order divisible by p. But then by the induction hypothesis ![]() /(a) would contain a Sylow p-group

/(a) would contain a Sylow p-group ![]() 1, and therefore would contain elements b(a) of order divisible by p. Then the order of b in

1, and therefore would contain elements b(a) of order divisible by p. Then the order of b in ![]() would be divisible by p. Therefore the order of

would be divisible by p. Therefore the order of ![]() is not divisible by p. If p†N then e is the Sylow p-group sought. If p/N then it follows from the class equation

is not divisible by p. If p†N then e is the Sylow p-group sought. If p/N then it follows from the class equation

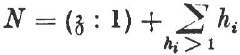

and from p † (3:1), p/N, that at least one hi > 1 is not divisible by p. ![]() contains a normalizer Ni of index hi > 1 and therefore Ni contains, by the induction hypothesis, a Sylow p-group

contains a normalizer Ni of index hi > 1 and therefore Ni contains, by the induction hypothesis, a Sylow p-group ![]() . Since p † hi,

. Since p † hi, ![]() is also a Sylow p-group of

is also a Sylow p-group of ![]() .

.

COROLLARY: For every prime divisor p of the order of a finite group there is an element of order p (Cauchy).

The order and exponent of a finite group have the same prime divisors.

It is a p-group if and only if its order is a power of p.

THEOREM 2: If ![]() is a Sylow p-group of

is a Sylow p-group of ![]() and

and ![]() a normal subgroup of

a normal subgroup of ![]() , then

, then ![]()

![]()

![]() is a Sylow p-group of

is a Sylow p-group of ![]() ;

; ![]()

![]() /

/![]() is a Sylow p-group of

is a Sylow p-group of ![]() /

/![]() .

.

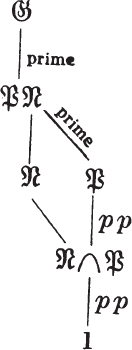

Proof:1 A subgroup ![]() of

of ![]() is a Sylow p-group if and only if

is a Sylow p-group if and only if

1. The order of ![]() is a power of p (written: pp),

is a power of p (written: pp),

2. The index of ![]() is prime to p (written: prime).

is prime to p (written: prime).

Now we may construct the diagram to the left and, observe first that ![]()

![]() :

:![]() is prime to p, and

is prime to p, and ![]() :

:![]()

![]()

![]() is a p-power. From the second isomorphism theorem it follows that

is a p-power. From the second isomorphism theorem it follows that ![]()

![]() :

:![]() is a p-power, and

is a p-power, and ![]() :

:![]()

![]()

![]() is prime to p, from which the theorem follows.

is prime to p, from which the theorem follows.

If a Sylow p-group ![]() is a normal subgroup of

is a normal subgroup of ![]() then it is the only Sylow p-group, since for every other Sylow p-group it

then it is the only Sylow p-group, since for every other Sylow p-group it ![]() 1 follows that

1 follows that ![]() 1

1![]() is of p-power order, but

is of p-power order, but ![]() :

:![]() 1

1![]() is prime to p; and therefore

is prime to p; and therefore ![]() 1

1![]() =

= ![]() =

= ![]() 1. Consequently a Sylow p-group Sp of a finite group

1. Consequently a Sylow p-group Sp of a finite group ![]() is the only Sylow p-group of its normalizer NP.

is the only Sylow p-group of its normalizer NP.

THEOREM 3: All Sylow p-groups of a finite group ![]() are conjugate under

are conjugate under ![]() . Their number when divided by p leaves a remainder 1.

. Their number when divided by p leaves a remainder 1.

Proof: Let the Sylow p-groups of ![]() be

be ![]() =

= ![]() 1, …,

1, …, ![]() r.

r.

Under the mapping ![]() of

of ![]() onto the group of inner automorphisms,

onto the group of inner automorphisms, ![]() is represented as a permutation group. Since conjugate subgroups have the same order, the

is represented as a permutation group. Since conjugate subgroups have the same order, the ![]() i are transformed into each other by

i are transformed into each other by ![]() , so that we obtain a representation Δ of

, so that we obtain a representation Δ of ![]() as a permutation group of degree r. By a remark above,

as a permutation group of degree r. By a remark above, ![]() transforms only

transforms only ![]() 1 and no other

1 and no other ![]() i into itself. Consequently there is only one system of transitivity of first degree. The other systems of transitivity of Δ have a degree > 1 which is a divisor of

i into itself. Consequently there is only one system of transitivity of first degree. The other systems of transitivity of Δ have a degree > 1 which is a divisor of ![]() : 1 and which, therefore, is a p-power. Consequently r ≡ 1 (p).

: 1 and which, therefore, is a p-power. Consequently r ≡ 1 (p).

![]() transforms the s =

transforms the s = ![]() :Np Sylow p-groups conjugate to

:Np Sylow p-groups conjugate to ![]() under

under ![]() among themselves, and as above it follows that s ≡ 1 (p). If there were another system of conjugate Sylow p-groups, then its members would be transformed into each other by

among themselves, and as above it follows that s ≡ 1 (p). If there were another system of conjugate Sylow p-groups, then its members would be transformed into each other by ![]() in systems of transitivity whose degree would be divisible by p. The system would therefore contain a number s1, divisible by p, of Sylow p-groups; on the other hand we conclude for s1, just as we did for s, that s1 ≡ 1 (p). Consequently all Sylow p-groups are conjugate to

in systems of transitivity whose degree would be divisible by p. The system would therefore contain a number s1, divisible by p, of Sylow p-groups; on the other hand we conclude for s1, just as we did for s, that s1 ≡ 1 (p). Consequently all Sylow p-groups are conjugate to ![]() , Q.E.D.

, Q.E.D.

THEOREM 4: Every p-group ![]() in

in ![]() is contained in a Sylow p-group.

is contained in a Sylow p-group.

Proof: We replace ![]() by

by ![]() in the proof of the previous theorem. Let the transformed objects again be

in the proof of the previous theorem. Let the transformed objects again be ![]() 1, …,

1, …, ![]() r. The degree of a system of transitivity of Δ is either 1 or a p-power. Since r ≡ 1 (p), there is certainly a system of transitivity of degree 1. Therefore there is a

r. The degree of a system of transitivity of Δ is either 1 or a p-power. Since r ≡ 1 (p), there is certainly a system of transitivity of degree 1. Therefore there is a ![]() i which is transformed into itself by all the elements of

i which is transformed into itself by all the elements of ![]() . Since

. Since ![]()

![]() i is a p-group which contains

i is a p-group which contains ![]() i, we have

i, we have ![]() , Q.E.D.

, Q.E.D.

THEOREM 5: Every subgroup ![]() of

of ![]() which contains the normalizer Np of a Sylow p-group Sp, is its own normalizer.

which contains the normalizer Np of a Sylow p-group Sp, is its own normalizer.

Proof: We must show that x ![]() x-1

x-1 ![]()

![]() implies

implies

x ![]()

![]() .

.

In any case Sp and xSpx-1 are Sylow p-groups of ![]() , and by Theorem 3 there is a U in

, and by Theorem 3 there is a U in ![]() such that U x Sp x-1U-1 = Sp;

such that U x Sp x-1U-1 = Sp;

therefore U x ![]() Np

Np ![]()

![]()

therefore x ![]()

![]() Q.E.D.

Q.E.D.

THEOREM 6: If the p-group ![]() contained in the finite group

contained in the finite group ![]() is not a Sylow p-group, then the normalizer N

is not a Sylow p-group, then the normalizer N![]() of

of ![]() is larger than

is larger than ![]() .

.

Proof: If p † ![]() : N

: N![]() then the theorem is clear; if, however

then the theorem is clear; if, however ![]() : N

: N![]() = pr, then

= pr, then ![]() transforms the pr subgroups conjugate to

transforms the pr subgroups conjugate to ![]() in systems of transitivity whose degrees are 1 or numbers divisible by p. Since

in systems of transitivity whose degrees are 1 or numbers divisible by p. Since ![]() is transformed into itself, there are at least p subgroups

is transformed into itself, there are at least p subgroups ![]() 1 =

1 = ![]() ,

, ![]() 2, …,

2, …, ![]() p, conjugate to

p, conjugate to ![]() which are transformed into themselves by

which are transformed into themselves by ![]() . Consequently N

. Consequently N![]() 2 is greater than

2 is greater than ![]() 2, and therefore N

2, and therefore N![]() is greater than

is greater than ![]() , Q.E.D.

, Q.E.D.

COROLLARIES:

1. Every maximal subgroup of a p-group is a normal subgroup; therefore it is of index p.

2. If a p-group is simple then it is of order p.

3. The composition factors of a p-group are of order p and therefore every p-group is solvable.

Information on the intersection of different Sylow p-groups is given by

THEOREM 7: In the normalizer of a maximal1 intersection ![]() of two different Sylow p-groups of

of two different Sylow p-groups of ![]() we have:

we have:

1. Every Sylow p-,group of N![]() contains

contains ![]() properly.

properly.

2. The number of Sylow p-groups of N![]() is greater than 1.

is greater than 1.

3. The intersection of two distinct Sylow p-groups of N![]() is equal to

is equal to ![]()

4. Every Sylow p-group of N![]() is the intersection of N

is the intersection of N![]() with exactly one Sylow p-group of

with exactly one Sylow p-group of ![]() .

.

5. The intersection of N![]() with a Sylow p-group of

with a Sylow p-group of ![]() which contains

which contains ![]() is a Sylow p-group of N

is a Sylow p-group of N![]() .

.

6. The normalizer of a Sylow p-group of N![]() in N

in N![]() is equal to the intersection of N

is equal to the intersection of N![]() with the normalizer of a Sylow p-group of

with the normalizer of a Sylow p-group of ![]() which contains

which contains ![]() .

.

Proof: ![]() is in a Sylow p-group

is in a Sylow p-group ![]() of

of ![]() and by hypothesis

and by hypothesis ![]() . Therefore by Theorem 6:

. Therefore by Theorem 6: ![]() .

. ![]() is a p-group in N

is a p-group in N![]() , thus by Theorem 4 it lies in a Sylow p-group

, thus by Theorem 4 it lies in a Sylow p-group ![]() of N

of N![]() . By Theorem 4,

. By Theorem 4, ![]() lies in a Sylow p-group

lies in a Sylow p-group ![]() of

of ![]() . Since

. Since ![]()

![]()

![]() contains

contains ![]() and thus is larger than

and thus is larger than ![]() ,

, ![]() =

= ![]() . Therefore

. Therefore ![]() =

= ![]() ∩ N

∩ N![]() =

= ![]() is a Sylow p-group of N

is a Sylow p-group of N![]() , and the

, and the ![]() in

in ![]() =

= ![]()

![]() N

N![]() is uniquely determined by

is uniquely determined by ![]() . Since every p-group in N

. Since every p-group in N![]() is in a Sylow p-group of

is in a Sylow p-group of ![]() , the intersection of two distinct Sylow p-groups of N

, the intersection of two distinct Sylow p-groups of N![]() is equal to

is equal to ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is the intersection of two different Sylow p-groups of

is the intersection of two different Sylow p-groups of ![]() , N

, N![]() contains several Sylow p-groups.

contains several Sylow p-groups. ![]() =

= ![]()

![]() N

N![]() is a normal subgroup of n

is a normal subgroup of n![]() = N

= N![]()

![]() N

N![]() . If we have

. If we have

![]()

for an x in N![]() , then it follows that

, then it follows that ![]() , and therefore by 4.,

, and therefore by 4., ![]() , consequently np = N

, consequently np = N![]()

![]() N

N![]() is the normalizer of p in N

is the normalizer of p in N![]() , Q.E.D.

, Q.E.D.

As an application of this theorem, we shall show that every group ![]() of order pnq is solvable (p, q are two distinct primes).

of order pnq is solvable (p, q are two distinct primes).

If a Sylow p-group ![]() is a normal subgroup, then

is a normal subgroup, then ![]() /

/ ![]() is cyclic and by Theorem 6, Corollary 3,

is cyclic and by Theorem 6, Corollary 3, ![]() is solvable. Hence

is solvable. Hence ![]() is solvable. Now suppose

is solvable. Now suppose ![]() is not a normal subgroup of

is not a normal subgroup of ![]() ; then

; then ![]() : N

: N![]() = q, N

= q, N![]() =

= ![]() .

.

If the intersection of any two different Sylow p-groups is 1, then there are 1 + q. (pn -1) elements of p-power order, and therefore there is at most one subgroup with order q. Consequently a Sylow q-group ![]() , is a normal subgroup of

, is a normal subgroup of ![]() , and

, and ![]() /

/![]() is isomorphic to

is isomorphic to ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() /

/![]() , and

, and ![]() are solvable,

are solvable, ![]() is also solvable. Finally let

is also solvable. Finally let ![]() be a maximal intersection of different Sylow p-groups greater than 1. The number of Sylow p-groups of N

be a maximal intersection of different Sylow p-groups greater than 1. The number of Sylow p-groups of N![]() is > 1, is not divisible by p, is a divisor of pnq and therefore is equal to q. Also it follows from the previous theorem that

is > 1, is not divisible by p, is a divisor of pnq and therefore is equal to q. Also it follows from the previous theorem that ![]() lies in q different Sylow p-groups of

lies in q different Sylow p-groups of ![]() . Therefore

. Therefore ![]() is the intersection of all the Sylow p-groups of

is the intersection of all the Sylow p-groups of ![]() .

. ![]() is a normal subgroup of

is a normal subgroup of ![]() , and the factor group

, and the factor group ![]() /

/![]() has as the maximal intersection of different Sylow p-groups the element 1. By what has already been proven,

has as the maximal intersection of different Sylow p-groups the element 1. By what has already been proven, ![]() /

/![]() is solvable. Moreover the p-group

is solvable. Moreover the p-group ![]() is solvable. Consequently

is solvable. Consequently ![]() is solvable, Q.E.D.

is solvable, Q.E.D.

For many applications the following theorem is useful:

THEOREM 8 (Burnside): If the p-group ![]() in the finite group

in the finite group ![]() is a normal subgroup of one Sylow p-group but is not a normal subgroup of another Sylow p-group, then there is a number r, relatively prime to p, of subgroups

is a normal subgroup of one Sylow p-group but is not a normal subgroup of another Sylow p-group, then there is a number r, relatively prime to p, of subgroups ![]() conjugate to

conjugate to ![]() which are all normal subgroups of

which are all normal subgroups of ![]() but which are not all normal subgroups of the same Sylow p-group of

but which are not all normal subgroups of the same Sylow p-group of ![]() , so that the normalizer of

, so that the normalizer of ![]() transforms the

transforms the ![]() i transitively among themselves.

i transitively among themselves.

Proof: Among the Sylow p-groups which contain ![]() as a non-normal subgroup,

as a non-normal subgroup, ![]() , is chosen so that the intersection

, is chosen so that the intersection ![]() of

of ![]() , with the normalizer N

, with the normalizer N![]() of

of ![]() is as large as possible. Let

is as large as possible. Let ![]() =

= ![]() 1,

1, ![]() 2, …,

2, …, ![]() s be the subgroups conjugate to

s be the subgroups conjugate to ![]() in the normalizer N

in the normalizer N![]() of

of ![]() . Along with

. Along with ![]() , all the

, all the ![]() i, are also normal subgroups of

i, are also normal subgroups of ![]() . The normalizer N

. The normalizer N![]() of

of ![]() contains N

contains N![]() . Let

. Let ![]() 1,

1, ![]() 2, …,

2, …, ![]() s, …,

s, …, ![]() r be all the groups conjugate to

r be all the groups conjugate to ![]() in N

in N![]() . Along with

. Along with ![]() , all the

, all the ![]() i are normal subgroups of

i are normal subgroups of ![]() .

. ![]() is contained in a Sylow p-group

is contained in a Sylow p-group ![]() * of N

* of N![]()

![]() N

N![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is not a Sylow p-group of

is not a Sylow p-group of ![]() , while, by hypothesis, a Sylow p-group of N

, while, by hypothesis, a Sylow p-group of N![]() is also a Sylow p-group of

is also a Sylow p-group of ![]() , then

, then ![]() * is larger than

* is larger than ![]() .

. ![]() * is in a Sylow p-group

* is in a Sylow p-group ![]() of N

of N![]()

![]() N

N![]() ,

, ![]() is in a Sylow p group

is in a Sylow p group ![]() of N

of N![]() and

and ![]() in a Sylow p-group of

in a Sylow p-group of ![]() of

of ![]() . Since the intersection of

. Since the intersection of ![]() with N

with N![]() contains

contains ![]() *, and therefore is larger than

*, and therefore is larger than ![]() , then by the construction of

, then by the construction of ![]() the Sylow p-group

the Sylow p-group ![]() of

of ![]() is contained in N

is contained in N![]() , and therefore a fortiori

, and therefore a fortiori ![]() is contained in N

is contained in N![]() .

.

Since ![]() contains the Sylow p-group

contains the Sylow p-group ![]() of N

of N![]()

![]() N

N![]() , we have

, we have ![]() =

= ![]() . Since therefore a Sylow p-group of N

. Since therefore a Sylow p-group of N![]()

![]() N

N![]() is already a Sylow p-group of

is already a Sylow p-group of ![]() is relatively prime to p. If all the

is relatively prime to p. If all the ![]() i were

i were

normal subgroups of the same Sylow p-group of ![]() , then the latter would be contained in N

, then the latter would be contained in N![]() . But then the groups

. But then the groups ![]() i conjugate to each other in N

i conjugate to each other in N![]() would be normal subgroups in all the Sylow p-groups of N

would be normal subgroups in all the Sylow p-groups of N![]() . Then

. Then ![]() would be a normal subgroup of the Sylow p-group

would be a normal subgroup of the Sylow p-group ![]() * of the intersection of N

* of the intersection of N![]() with

with ![]() . But

. But ![]() * is larger than

* is larger than ![]() , and this contradicts the definition of

, and this contradicts the definition of ![]() , as the intersection of

, as the intersection of ![]() with N

with N![]() ; therefore the

; therefore the ![]() i are not all normal subgroups of the same Sylow p-group of

i are not all normal subgroups of the same Sylow p-group of ![]() , Q.E.D.

, Q.E.D.

The positional relationships of the subgroups of ![]() constructed in this proof can be seen from the diagram on the left.

constructed in this proof can be seen from the diagram on the left.

1. Nilpotent Groups.

Fundamental for the theory of p-groups is the following statement:

THEOREM 9: The center of a p-group different from e is itself different from e.

Proof: From the class equation for a group of order pn > 1:

![]()

where the summands pi run through indices > 1 of certain normalizers. Therefore ![]() : 1 is divisible by p, and consequently

: 1 is divisible by p, and consequently ![]()

![]() e.

e.

COROLLARY:The (n + 1)-th member of the ascending central series of a group ![]() of order pn is equal to the whole group.

of order pn is equal to the whole group.

The members of the ascending central series are defined as the normal subgroups ![]() i of

i of ![]() such that

such that ![]() is the center of

is the center of ![]() /

/![]() i. Now either

i. Now either ![]() i =

i = ![]() or, as just proven,

or, as just proven, ![]() i + 1 is larger than

i + 1 is larger than ![]() i, and therefore certainly

i, and therefore certainly ![]() n =

n = ![]() .

.

By refinement of the ascending central series of a p-group we obtain a principal series in which every factor is of order p. It follows from the Jordan - Hölder - Schreier theorem that:

Every principal series of a p-group has steps of prime order.

The index of the center of a non-abelian p-group is divisible by p2. This follows from the useful lemma: If a normal subgroup ![]() of a group

of a group ![]() is contained in the center and has a cyclic factor group, then

is contained in the center and has a cyclic factor group, then ![]() is abelian. Since

is abelian. Since ![]() /

/![]() is generated by a coset A

is generated by a coset A![]() , all the elements of

, all the elements of ![]() are of the form AiZ where Z is in the center.

are of the form AiZ where Z is in the center.

Therefore

![]()

and ![]() is abelian

is abelian

If we apply the result found above to a p-group in which ![]() then:

then: ![]() and since

and since ![]() is abelian, it follows that:

is abelian, it follows that:

The factor commutator group of a non-abelian p-group has an order divisible by p2.

A group of order p or p2 is abelian. In a non-abelian group of order p3, the center and the commutator group are identical and are of order p.

DEFINITION: A group ![]() is said to be nilpotent1 if the ascending central series contains the whole group as a member, i.e., if

is said to be nilpotent1 if the ascending central series contains the whole group as a member, i.e., if

![]()

The uniquely determined number c is called, following Hall, the class of the group. Therefore “nilpotent of class 1” is the same as “abelian ![]() e.”

e.”

THEOREM 10: In a nilpotent group of class c it is possible to ascend to the whole group from any subgroup by forming normalizers at most c times.

Proof: Let ![]() be nilpotent of class c; let

be nilpotent of class c; let ![]() be a subgroup. Certainly

be a subgroup. Certainly ![]() 0 is contained in

0 is contained in ![]() . If

. If ![]() i is already contained in

i is already contained in ![]() , then by the definition of

, then by the definition of ![]() i + 1, it follows that

i + 1, it follows that ![]() i + 1 is contained in the normalizer of

i + 1 is contained in the normalizer of ![]() . By at most c repetitions of this procedure we obtain the result.

. By at most c repetitions of this procedure we obtain the result.

COROLLARY: Every maximal subgroup of a nilpotent group is a normal subgroup and therefore is of prime index.

Therefore in a p-group ![]() the intersection of all the normal subgroups of index p is equal to the Φ-subgroup defined earlier. The factor group

the intersection of all the normal subgroups of index p is equal to the Φ-subgroup defined earlier. The factor group ![]() /Φ is an abelian group of exponent p. By its order pd the important invariant d = d(

/Φ is an abelian group of exponent p. By its order pd the important invariant d = d(![]() ) is defined. The significance of d is made clear by the following BURNSIDE BASIS THEOREM: From every system of generators of

) is defined. The significance of d is made clear by the following BURNSIDE BASIS THEOREM: From every system of generators of ![]() exactly d can be selected so that these alone generate

exactly d can be selected so that these alone generate ![]() . By the general basis theorem this theorem need only be proven for

. By the general basis theorem this theorem need only be proven for ![]() /Φ.

/Φ.

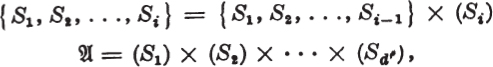

An abelian group ![]() with prime exponent p is called an elementary abelian group. If

with prime exponent p is called an elementary abelian group. If ![]() is of order pd then it is possible to generate

is of order pd then it is possible to generate ![]() by d elements: Let S1 be an element

by d elements: Let S1 be an element ![]() e in

e in ![]() : let S2 be an element

: let S2 be an element ![]() not in (S1); let S3 be an element of

not in (S1); let S3 be an element of ![]() not in {S1, S2}; let Sd′ be an element of

not in {S1, S2}; let Sd′ be an element of ![]() not in {S1, S2, …, Sd′-1} and {S1, S2, …, Sd′-1} =

not in {S1, S2, …, Sd′-1} and {S1, S2, …, Sd′-1} = ![]() . Then (Si) is of prime order p so that we must have

. Then (Si) is of prime order p so that we must have

![]()

It follows from this that

and since ![]() : 1 = pd, , we see that d = d1. Therefore a finite elementary abelian group is the direct product of a finite number of cyclic groups of prime order. Conversely a direct product of a finite number of cyclic groups (S1), (S2), …, (Sd) of order p is an elementary abelian group. The elements S1, S2, …, Sd in the direct product representation are said to be a basis of

: 1 = pd, , we see that d = d1. Therefore a finite elementary abelian group is the direct product of a finite number of cyclic groups of prime order. Conversely a direct product of a finite number of cyclic groups (S1), (S2), …, (Sd) of order p is an elementary abelian group. The elements S1, S2, …, Sd in the direct product representation are said to be a basis of ![]() . The above method of construction shows that every generating system of

. The above method of construction shows that every generating system of ![]() contains a basis. Therefore d is the minimal number of generators. Consequently every system of d generators is a basis of

contains a basis. Therefore d is the minimal number of generators. Consequently every system of d generators is a basis of ![]() . The number of basis systems of

. The number of basis systems of ![]() can be calculated easily:

can be calculated easily:

In the above construction there are pd-1 possibilities for S1; after choosing S1, there are pd-p possibilities for S2 and so forth, so that we obtain the number (pd – 1) (pd – p)· … · (pd – pd−1) as the number of basis systems of ![]() . If S1, S2, …, Sd is a fixed basis and T1, T2, …, Td is an arbitrary basis then the mapping

. If S1, S2, …, Sd is a fixed basis and T1, T2, …, Td is an arbitrary basis then the mapping

![]()

defines an automorphism of ![]() and conversely. Therefore it follows that:

and conversely. Therefore it follows that:

The number of automorphisms of an elementary abelian group of order pd is equal to ![]() . If we set

. If we set

![]()

then the number is equal to ![]() . From the general basis theorem in II, § 4, it follows that:

. From the general basis theorem in II, § 4, it follows that:

The number of automorphisms of a p-group of order pn (n > 0) and d generators is a divisor of

![]()

Remark: The highest power of p which divides this number is ![]() , and since 0 < d

, and since 0 < d ![]() n, this number is a divisor of

n, this number is a divisor of ![]() , as can easily be seen. Therefore the number of automorphisms of an arbitrary group of order pn is a divisor of the number of automorphisms of the elementary abelian group of order pn.

, as can easily be seen. Therefore the number of automorphisms of an arbitrary group of order pn is a divisor of the number of automorphisms of the elementary abelian group of order pn.

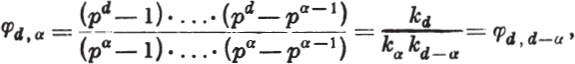

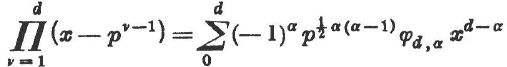

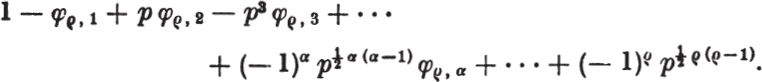

For later theorems it is important to obtain several formulae about the number φq, α of subgroups of order pα in the elementary abelian group of order pd. Let 0 < α ![]() d. Every subgroup of order pα is elementary.

d. Every subgroup of order pα is elementary.

If S1, S2, …, Sa are the first α elements of a basis of the whole group, then these α elements are a basis of a subgroup of order pα. Conversely, as we have seen previously, every basis of a subgroup of order pα can be extended to a basis of the whole group. Since the elements S1, S2, …, Sα can be chosen in

![]()

different ways, and every subgroup of order pα has ![]() different basis systems, then

different basis systems, then

(1)

where k0 = 1. From this the reader can derive the recursion formula

(2) ![]()

for ![]() , where

, where ![]() If we set

If we set ![]() for rational integers α which are larger than d or smaller than 0, then the formula is valid generally. From this formula we derive the congruence

for rational integers α which are larger than d or smaller than 0, then the formula is valid generally. From this formula we derive the congruence

(3) ![]()

and the polynomial identity

(4)

by induction. If we set x = 1, then

(5) ![]()

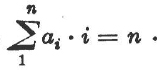

An abelian group of order pn can be decomposed, by the basis theorem, into the direct product of cyclic groups of orders pn1, pn2, …, pnr. Here the exponents n1, n2, …, nr are determined uniquely to within order. Therefore we say: The group is of type (pn1, pn2, …, pnr). If we order the by size so that pj occurs aj times as the order of a basis element, then we say: The group is of type

![]()

Here the non-negative integers αi are bound only by the relation

3. Finite Nilpotent Groups.

The direct product of a finite number of nilpotent groups is nilpotent, as is easily seen. For example, the direct product of a finite number of p-groups is nilpotent. The following converse is important:

THEOREM 11: Every finite nilpotent group is the direct product of its Sylow groups.

Proof: The normalizer of a Sylow group is its own normalizer by Theorem 5, and therefore, by Theorem 10, it is equal to the whole group; consequently every Sylow group is a normal subgroup.

Let p1, p2, …, pr be the various prime divisors of the group order, and assume we have already shown that

![]()

Then the normal subgroups Sp1 · Sp2 · … · Spi and SPi+1 have relatively prime orders so that their intersection is e; and therefore

![]()

But from the equation ![]() it follows, by comparing the orders, that the whole group is the direct product of its Sylow groups.

it follows, by comparing the orders, that the whole group is the direct product of its Sylow groups.

THEOREM 12: The Φ-subgroup of a nilpotent group contains the commutator group.

Proof: As we saw earlier, the Φ-subgroup is equal to the intersection of the whole group with its maximal subgroups. By the Corollary to Theorem 10, every maximal subgroup of a nilpotent group is a normal subgroup of prime index, and therefore every maximal subgroup of a nilpotent group contains the commutator group. Consequently the Φ-subgroup of a nilpotent group contains the commutator group.

Remark: We have further that ![]() , which can be derived from the definition of the Φ-subgroup as the intersection of the whole group with its maximal subgroups.

, which can be derived from the definition of the Φ-subgroup as the intersection of the whole group with its maximal subgroups.

For finite groups we have the converse:

THEOREM 13 (Wieland): If the Φ-subgroup of a finite group contains the commutator group, then the group is nilpotent.

Proof: As in the proof of Theorem 11 it suffices to prove that every Sylow group is a normal subgroup. If the normalizer of a Sylow group were not the whole group, then it would be contained in a maximal subgroup which on the one hand would contain the Φ-subgroup and therefore the commutator group; and on the other hand, by Theorem 5, must be its own normalizer. Since this is not possible, every Sylow group must be a normal subgroup of the whole group.

THEOREM 14 (Hall): If the normal subgroup ![]() is not contained in

is not contained in ![]() i but is contained in

i but is contained in ![]() i + 1, then the following is a normal subgroup chain without repetitions:

i + 1, then the following is a normal subgroup chain without repetitions: ![]()

Proof: We have ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() is not contained in

is not contained in ![]() i, (

i, (![]() ,

, ![]() ) is not contained in

) is not contained in ![]() i–1, and therefore

i–1, and therefore ![]() is not contained in

is not contained in ![]() . We apply the same argument to

. We apply the same argument to ![]() , etc., Q.E.D.

, etc., Q.E.D.

4. Maximal abelian normal subgroups.

It is natural to consider the maximal abelian normal subgroups as well as the maximal abelian factor group. In general abelian normal subgroups which are contained in no other abelian normal subgroup are neither uniquely determined nor isomorphic to each other, as is easily seen in the example of the dihedral group of eight elements. The center seems to be more appropriate as a counterpart of the factor commutator group, as we already have seen in the theorems on direct products.

In any case, there is, in every group whose elements e = a1, a2, …, are well ordered, a maximal abelian normal subgroup. We can construct an abelian normal subgroup ![]() ω for any index ω in the following way:

ω for any index ω in the following way: ![]() 1 = e; let

1 = e; let ![]() ω be the union of all

ω be the union of all ![]() r with v < ω; let

r with v < ω; let ![]() ω be equal to the normal subgroup generated by

ω be equal to the normal subgroup generated by ![]() ω and aω if this normal subgroup is abelian. Otherwise let =

ω and aω if this normal subgroup is abelian. Otherwise let = ![]() ω =

ω = ![]() ω. The union of all the

ω. The union of all the ![]() ω is a maximal abelian normal subgroup.

ω is a maximal abelian normal subgroup.

A maximal abelian normal subgroup of a nilpotent group is its own centralizer.

Proof: The centralizer ![]() is a normal subgroup of

is a normal subgroup of ![]() . If

. If ![]() contained

contained ![]() properly, then by Theorem 14, a center element X

properly, then by Theorem 14, a center element X ![]() in

in ![]() /

/![]() would be contained in

would be contained in ![]() /

/![]() 1 so that the subgroup generated by X and

1 so that the subgroup generated by X and ![]() would be larger than

would be larger than ![]() . But since this subgroup containing

. But since this subgroup containing ![]() would also be an abelian normal subgroup, we must have

would also be an abelian normal subgroup, we must have ![]() =

= ![]() .

.

If ![]() and

and ![]() are of orders pn and pm, respectively then the index pn–m is a divisor of the number of automorphisms of

are of orders pn and pm, respectively then the index pn–m is a divisor of the number of automorphisms of ![]() , whereupon, by Part 2, it follows that

, whereupon, by Part 2, it follows that

5. The automorphism group of ZN.

We wish to determine the automorphism group of the cyclic group ZN for N > 1. For this purpose we consider ZN as the residue class module (quotient module) ![]() of the additive group of integers with respect to the submodule of integers divisible by N. The operators of ZN are given by the multiplications

of the additive group of integers with respect to the submodule of integers divisible by N. The operators of ZN are given by the multiplications ![]() by the rational integers t;

by the rational integers t; ![]() and

and ![]() are equal if and only if t1 and t2 are congruent mod N.

are equal if and only if t1 and t2 are congruent mod N. ![]() is an automorphism if and only if t is relatively prime to N. The number φ(N) of automorphisms of ZN is equal to the number of residue classes (cosets) mod N which contain numbers relatively prime to N (prime residue classes).

is an automorphism if and only if t is relatively prime to N. The number φ(N) of automorphisms of ZN is equal to the number of residue classes (cosets) mod N which contain numbers relatively prime to N (prime residue classes).

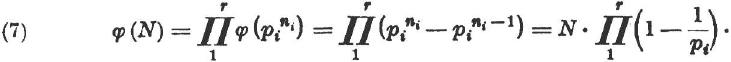

The automorphism group of ZN (cyclic group of order N) is isomorphic to the group of prime residue classes mod N. If N is the product of relatively prime numbers m1, m2, then ZN is the direct product of two characteristic cyclic groups of orders m1, m2. For the automorphism group we have the corresponding situation; in particular

![]()

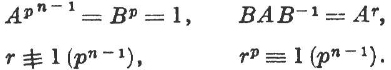

If N is the n-th power of a prime p then a residue class is prime if and only if it consists of numbers relatively prime to p; the number of these residue classes is pn – pn – 1. If ![]() is the prime power decomposition, then

is the prime power decomposition, then

The residue class ring ![]() is a field and therefore, by II, § 7, the automorphism group of Zp is cyclic of order p–1. A rational number g whose order mod p is p–1 is said to be a primitive congruence root mod p. g has an order which is divisible by p–1 mod pn; say therefore, it has the order (p — 1) · pr. The order of

is a field and therefore, by II, § 7, the automorphism group of Zp is cyclic of order p–1. A rational number g whose order mod p is p–1 is said to be a primitive congruence root mod p. g has an order which is divisible by p–1 mod pn; say therefore, it has the order (p — 1) · pr. The order of ![]() is then equal to p-1, mod pn. If a = 1 + kpm, then it follows from the binomial theorem that

is then equal to p-1, mod pn. If a = 1 + kpm, then it follows from the binomial theorem that ![]() . Therefore a ≡ l(pm) implies that

. Therefore a ≡ l(pm) implies that ![]() . However if m > 1 or if p is odd then

. However if m > 1 or if p is odd then ![]() implies that

implies that ![]() . If p is odd, then 1 + p is of order pn–1 mod pn, (1 + p).g1 is of order

. If p is odd, then 1 + p is of order pn–1 mod pn, (1 + p).g1 is of order ![]() . If p = 2, then 1 + 22 is of order 2n–2 mod 2n (n > 2). Since –1 is congruent to no power of 5 mod 4, there are, mod 2n, the 2n–1 different prime residue classes

. If p = 2, then 1 + 22 is of order 2n–2 mod 2n (n > 2). Since –1 is congruent to no power of 5 mod 4, there are, mod 2n, the 2n–1 different prime residue classes ![]() . As a result we obtain:

. As a result we obtain:

If n < 3 or p is odd, then the automorphism group of ![]() is cyclic of order (p — l)pn–1. The automorphism group of Z2n, for n > 2, is abelian of type (2n–2, 2) with the associated basis automorphisms 5 and –1.

is cyclic of order (p — l)pn–1. The automorphism group of Z2n, for n > 2, is abelian of type (2n–2, 2) with the associated basis automorphisms 5 and –1.

6. p-Groups with only one Subgroup of Order p.

A non-cyclic abelian group of exponent pn contains at least two different subgroups of order p.

Proof: Let A be an element of order pn and let B not be a power of A. Then the order pr of B mod (A) is greater than 1, but at most pn. We have

![]()

Therefore ![]() and

and ![]() generate two different subgroups of order p.

generate two different subgroups of order p.

We wish to find non-abelian groups of order pn which contain only one subgroup of order p.

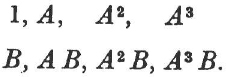

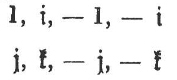

An example is the quaternion group. By the theorem of Hölder it is defined by the relations ![]() as a group of order 8 with generators A and B. Its eight elements are called quaternions; they are

as a group of order 8 with generators A and B. Its eight elements are called quaternions; they are

If instead we write

![]()

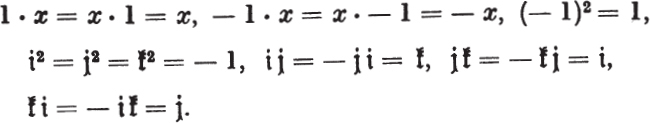

then we have the following calculational rules:

From this we conclude that there is only one subgroup of order 2 and exactly three subgroups of order 4. The center is equal to the commutator group which is equal to (—1).

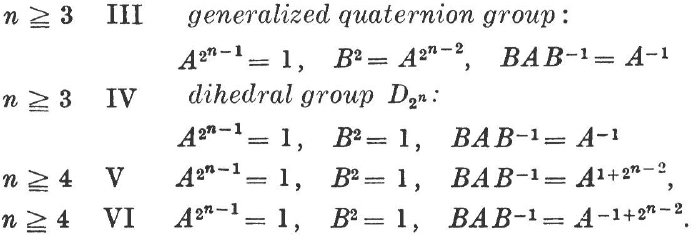

The generalized quaternion group is defined by the relations

![]()

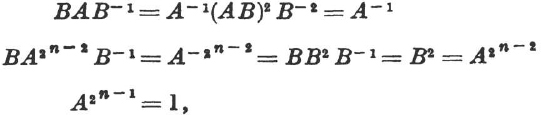

as a group generated by A, B, and of order 2n, by the Hölder Theorem. Since

![]()

this group contains only one subgroup of order 2. The elements ![]() and B generate a quaternion group.

and B generate a quaternion group.

The relations above can be written more elegantly in the form

![]()

The new relations follow from those above.

From the new relations, however, it follows that

and therefore the old relations follow.

If A′ is of order 2n–1, B′ of order 4, and if A′ and B′ generate the whole group, then

![]()

Therefore all the calculational rules which are valid for power products of A and B also remain valid for the corresponding power products of A′ and B′

Since A′ and B′ generate the whole group, (A′) is a normal subgroup of index 2, and every element can be written uniquely in the form

![]()

Therefore the mapping ![]() is an automorphism of the group. The number of all the automorphisms is equal to the number of pairs A′, B′ It follows by simple enumeration that:

is an automorphism of the group. The number of all the automorphisms is equal to the number of pairs A′, B′ It follows by simple enumeration that:

The quaternion group has exactly 24 automorphisms. The generalized quaternion group of order 2n has exactly 22n–3 automorphisms for n > 3.

In the automorphism group A of the quaternion group, the inner automorphisms form an abelian normal subgroup J of order 4. An automorphism which commutes with all the inner automorphisms is itself an inner automorphism. Since it changes each generator by a factor in the center, there are at most 2·2 such automorphisms.

A group A having order 24, and containing a normal subgroup J of order 4 which is its own centralizer, must be isomorphic to ![]() 4.

4.

This is because a central element of A must be in J, and an element of order 3 must transform the three elements ![]() e in J in a cyclic manner. Then, since according to the results of Sylow there are elements of order 3, the center is e, and there is no normal subgroup of order 3. From these results also, the index in A of the normalizer N3 of a Sylow 3-group is 4. A transitive representation of A in 4 letters is associated with N3. The representation is faithful since the intersection of all 3-normalizers contains only center elements with orders 1 or 2 and therefore is e. Since A consists of 24 elements, A is isomorphic to

e in J in a cyclic manner. Then, since according to the results of Sylow there are elements of order 3, the center is e, and there is no normal subgroup of order 3. From these results also, the index in A of the normalizer N3 of a Sylow 3-group is 4. A transitive representation of A in 4 letters is associated with N3. The representation is faithful since the intersection of all 3-normalizers contains only center elements with orders 1 or 2 and therefore is e. Since A consists of 24 elements, A is isomorphic to ![]() 4.

4.

The automorphism group of the quaternion group is isomorphic to the symmetric permutation group of four letters.

The quaternion group is the only p-group tvhich contains two different cyclic subgroups of index p but only one subgroup of order p.

Proof:1 Let ![]() be of order pn and let it contain two different cyclic subgroups

be of order pn and let it contain two different cyclic subgroups ![]() 1 and

1 and ![]() 2, of index p.

2, of index p. ![]() 1 and

1 and ![]() 2 are different normal subgroups of index p, and therefore their intersection

2 are different normal subgroups of index p, and therefore their intersection ![]() is of index p2. Moreover

is of index p2. Moreover ![]() is in the center and contains the commutator group. It follows for any two elements x, y that xp and yp are in

is in the center and contains the commutator group. It follows for any two elements x, y that xp and yp are in ![]() , and that

, and that

![]()

If p is odd, then (xy)p = xpyp, and therefore the operation of raising to power p is a homomorphy. Since the group of p-th powers is contained in ![]() , by the first isomorphism theorem the elements whose p-th power is e form a subgroup whose order is at least p2 There are at least two different subgroups of order p in this subgroup.

, by the first isomorphism theorem the elements whose p-th power is e form a subgroup whose order is at least p2 There are at least two different subgroups of order p in this subgroup.

If p = 2, then (xy)4 = (y, x)4 x4y4 = x4y4. Now we conclude just as above that either ![]() = 1 and

= 1 and ![]() 1,

1, ![]() 2 are two different subgroups of order 2, or there are two subgroups

2 are two different subgroups of order 2, or there are two subgroups ![]() 1

1 ![]()

![]() 2 of order 4 by the first isomorphism theorem. We may assume that

2 of order 4 by the first isomorphism theorem. We may assume that ![]() 1 is in

1 is in ![]() . If

. If ![]() 1 is different from

1 is different from ![]() 1, then

1, then ![]() 1 is in

1 is in ![]() and

and ![]() 1 ·

1 · ![]() 2 is an abelian group of order 8. Since it contains two different subgroups of index 2, it is not cyclic, and therefore it also contains two different subgroups of order 2. If, in conclusion,

2 is an abelian group of order 8. Since it contains two different subgroups of index 2, it is not cyclic, and therefore it also contains two different subgroups of order 2. If, in conclusion, ![]() 1 =

1 = ![]() 1, then the whole group is of order 8. Let

1, then the whole group is of order 8. Let ![]() = (A) and

= (A) and ![]() 2 = (B). If there is only one subgroup of order 2 then B2 = (A B)2 = A2, and therefore the group is the quaternion group.

2 = (B). If there is only one subgroup of order 2 then B2 = (A B)2 = A2, and therefore the group is the quaternion group.

THEOREM 15: A p-group which contains only one subgroup of order p is either cyclic or a generalized quaternion group.

Proof: Let ![]() be of order pn and let it contain only one subgroup of order p. First let p be odd. If n = 0, 1, then the theorem is clearly true. We now apply induction to n.

be of order pn and let it contain only one subgroup of order p. First let p be odd. If n = 0, 1, then the theorem is clearly true. We now apply induction to n.

Every subgroup of index p is cyclic by the induction hypothesis, and therefore by what was proven previously there is only one subgroup of index p in and ![]() , therefore

, therefore ![]() itself is cyclic.1

itself is cyclic.1

Now let p = 2 and let ![]() be a maximal abelian normal subgroup.

be a maximal abelian normal subgroup. ![]() is cyclic and its own centralizer. Therefore

is cyclic and its own centralizer. Therefore ![]() /

/![]() is isomorphic to a group of automorphisms of

is isomorphic to a group of automorphisms of ![]() . We shall show that only one automorphism of order 2 can occur, namely, the operation of a raising the elements of

. We shall show that only one automorphism of order 2 can occur, namely, the operation of a raising the elements of ![]() to the power –1. Since this automorphism is not the square of any other automorphism of

to the power –1. Since this automorphism is not the square of any other automorphism of ![]() , it follows that

, it follows that ![]() :

: ![]() is either 1 or 2. If we set

is either 1 or 2. If we set ![]() = (A) and assume that B

= (A) and assume that B ![]() e(

e(![]() ), B2 ≡ e(

), B2 ≡ e(![]() ), then as a preliminary BAB–1 must be shown to be equal to A–1. In fact, we want to show further that the group generated by A and B is a generalized quaternion group with relations (8) and (9). Then the theorem will be proven.

), then as a preliminary BAB–1 must be shown to be equal to A–1. In fact, we want to show further that the group generated by A and B is a generalized quaternion group with relations (8) and (9). Then the theorem will be proven.

Since B cannot commute with all the elements of A, (B2) ![]() A, and there is a subgroup

A, and there is a subgroup ![]() 1 of

1 of ![]() which contains (B2) as a subgroup of index 2. The group

which contains (B2) as a subgroup of index 2. The group ![]() 1(B) contains the two different cyclic subgroups

1(B) contains the two different cyclic subgroups ![]() 1 and (B) of index 2; and therefore it is, as was previously shown, the quaternion group. If A is of order 2m then: B2 = A2m – 1. We also conclude (AB)2 = A2m – 1 Therefore A and B generate the generalized quaternion group of order 2m + 1.

1 and (B) of index 2; and therefore it is, as was previously shown, the quaternion group. If A is of order 2m then: B2 = A2m – 1. We also conclude (AB)2 = A2m – 1 Therefore A and B generate the generalized quaternion group of order 2m + 1.

THEOREM 16: A group of order pn is cyclic if it contains only one subgroup of order pm (where 1 < m < n).

Proof: There is a subgroup ![]() of order pm.

of order pm. ![]() is contained in a subgroup

is contained in a subgroup ![]() 1 of order pm + 1 and is the only subgroup of index p in

1 of order pm + 1 and is the only subgroup of index p in ![]() 1. Therefore

1. Therefore ![]() 1 is cyclic and consequently

1 is cyclic and consequently ![]() is cyclic. Since every subgroup of order p or p2 is contained in a subgroup of order pm, and since the only subgroup of order pm is cyclic, there is only one subgroup of order p and one of order p2. Since the generalized quaternion group contains some subgroups of order 4, we conclude from the previous theorem that the whole group is cyclic.

is cyclic. Since every subgroup of order p or p2 is contained in a subgroup of order pm, and since the only subgroup of order pm is cyclic, there is only one subgroup of order p and one of order p2. Since the generalized quaternion group contains some subgroups of order 4, we conclude from the previous theorem that the whole group is cyclic.

If in a p-group, every subgroup of order p2 is cyclic, then there is only one subgroup of order p, and conversely.

If there were two different subgroups of order p then we can assume that one of them is contained in the center. But then the product of the two subgroups is a non-cyclic group of order p2. Conversely, in a non-cyclic group of order p2 there are certainly two different subgroups of order p. Now one can easily prove:

THEOREM 17: A group of order pn in which every subgroup of order pm is cyclic, where 1 < m < n, is cyclic except in the case p = 2, m = 2 in which case the group can also be a generalized quaternion group.

7. p-Groups with a Cyclic Normal Subgroup of Index p.

We shall determine all the p-groups which contain a cyclic normal subgroup of index p. This problem will now be solved for non-abelian p-groups, which contain some subgroups of order p. If ![]() is of order pn then in

is of order pn then in ![]() there is an element A of order pn – 1 and an element B of order p which is not a power of A. A and B generate

there is an element A of order pn – 1 and an element B of order p which is not a power of A. A and B generate ![]() , and the subgroup (A) of index p is a normal subgroup. Therefore

, and the subgroup (A) of index p is a normal subgroup. Therefore

If for odd p the element B is replaced by an appropriate power, then we can take r = 1 + pn – 2.

If p = 2, n = 3, then we must have r ≡ — 1 (4). If p = 2, n > 3, then there are three possibilities for r,

![]()

The number r is not altered mod 2n – 1 if B is replaced by BAμ.

If ![]() then the commutator subgroup is of order 2; in the other two cases it is of order 2n –1.

then the commutator subgroup is of order 2; in the other two cases it is of order 2n –1.

If r ≡ — 1, then ![]() and therefore there is only one cyclic subgroup of index 2. Thus r is uniquely determined by the group. As a result we obtain:

and therefore there is only one cyclic subgroup of index 2. Thus r is uniquely determined by the group. As a result we obtain:

The groups ![]() of order pu – 1 which contain an element A of order pu –1, are of the following types:

of order pu – 1 which contain an element A of order pu –1, are of the following types:

a) ![]() abelian:

abelian:

b) ![]() non abelian, p odd:

non abelian, p odd:

![]()

c) ![]() non-abelian, p = 2:

non-abelian, p = 2:

Groups of different type are not isomorphic. From Hölder’s theorem it follows that all types exist. For n = 3, V will coincide with IV, and VI with II.

Now it is simple to give all groups of order p3. We must now investigate among such all those in which the p-th power of every element is e. A group in which all squares are equal to e is abelian since

![]()

If the group is non-abelian and p is odd, then it is generated by two elements A and B such that the relations

![]()

hold. By III, Theorem 21, these relations define a non-abelian group with generators A, B and order p3, in which, for any two elements x, y, we have:

![]()

Thus the p-th power of every element is equal to e. As a result we obtain:

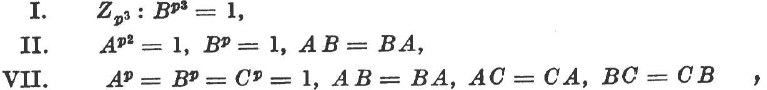

There are p for every prime number p, five types of groups of order p3, namely the three abelian types:

and two non-abelian types, which are, for p = 2; III, quaternion group and IV, the dihedral group, and for odd p the types

1. If a p-group contains a cyclic normal subgroup of index p, then every subgroup different from e has the same property.

2. For odd p, the following properties hold for abelian groups of type (p, pn – 1) and for non-abelian groups of order pn having a cyclic subgroup of index p, where m is a number greater than zero and less than n:

a) The number of subgroups of order pm is 1 + p in both cases.

b) The number of cyclic subgroups of order pm is, in both cases, 1 + p or p according to whether m = 1 or m > 1.

c) The number of elements whose pm-th power = e is pm + 1 in both cases.

d) In both groups, every subgroup whose order is divisible by p2 is a normal subgroup. Therefore for m > 1 there are equally many normal subgroups of order pm.

e) The number of automorphisms is pn(p-1).

3. The two types of non-abelian groups of order p3 can be defined by the relations

for all p by an appropriate choice of generators A, B.

4. If a 2-group contains a cyclic subgroup of index 2 and is neither abelian of type (2, 2) nor the quaternion group, then the number of its automorphisms is a power of 2.

5. In a finite group, the index of the normalizer over the centralizer of a Sylow p-group with d generators is a divisor of kd. If the order of the group is divisible neither by the third power of its smallest prime factor p, nor by 12, then every Sylow p-group is in the center of its normalizer.

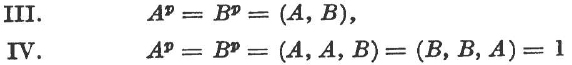

6. In an abelian p-group ![]() with the exponent pm, the characteristic chains

with the exponent pm, the characteristic chains

and

give rise to a characteristic series through the refinement process which was given in the proof of the Jordan-Hölder-Schreier Theorem. There is only this one characteristic series. (Here ![]() pv denotes the group of the pr-th powers and

pv denotes the group of the pr-th powers and ![]() pv denotes the group of all elements whose pv-th power is e.)

pv denotes the group of all elements whose pv-th power is e.)

7. Theorem 2 in § 1 admits the following corollaries: If ![]() is a Sylow p-group, in

is a Sylow p-group, in ![]() , N

, N![]() its normalizer,

its normalizer, ![]() a normal subgroup of

a normal subgroup of ![]() , then

, then

a) N![]()

![]() /

/![]() is the normalizer of the Sylow p-group of

is the normalizer of the Sylow p-group of ![]()

![]() /

/![]() of

of ![]() /

/![]() ;

;

b) N![]() is contained in the normalizer N

is contained in the normalizer N![]() of the Sylow p-group

of the Sylow p-group ![]() =

= ![]() ∩

∩ ![]() of

of ![]() ;

;

c) N![]()

![]() =

= ![]() ; therefore by the Second Isomorphism Theorem

; therefore by the Second Isomorphism Theorem

![]()

(Hint for a): If x![]()

![]() x–1 =

x–1 = ![]()

![]() , then by Theorem 3: x

, then by Theorem 3: x![]() x–1 = v

x–1 = v![]() v–1 is solvable for v in

v–1 is solvable for v in ![]() , therefore v–1x

, therefore v–1x ![]() : for every x in

: for every x in ![]() , x

, x![]() x–1 = v

x–1 = v![]() v–1 is solvable for v in

v–1 is solvable for v in ![]() .)

.)

With the help of c) it should be shown that the φ-subgroup of a finite group is nilpotent.

In the study of finite groups the question arises naturally as to the number of elements or subgroups with some given property. The results obtained in connection with this question do not lie very deep.

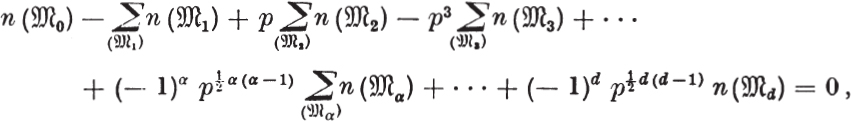

The following systematic derivation of the enumeration theorems in p-groups is due to P. Hall.

THEOREM 18: (Counting Principle): Let ![]() be a finite p-group.

be a finite p-group. ![]() α denotes any subgroup of index pα which contains Φ(

α denotes any subgroup of index pα which contains Φ(![]() ). Let (

). Let (![]() ) be a set of complexes such that each complex

) be a set of complexes such that each complex ![]() in (

in (![]() ) is contained in at least one subgroup of index p. Let n(

) is contained in at least one subgroup of index p. Let n(![]() α) be the number of complexes of (

α) be the number of complexes of (![]() ) which are contained in

) which are contained in ![]() α. Then

α. Then

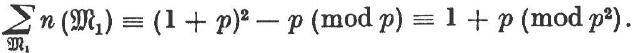

where the summation ![]() is extended over the φd, α subgroups

is extended over the φd, α subgroups ![]() α of

α of ![]() .

.

Proof: We shall show that the number of times that an element ![]() in (

in (![]() ) is “counted” with the appropriate sign on the left of the equation above is equal to zero.

) is “counted” with the appropriate sign on the left of the equation above is equal to zero.

The intersection of all ![]() α which contain

α which contain ![]() , contains φ(

, contains φ(![]() ) and therefore is an

) and therefore is an ![]()

![]() . By hypothesis

. By hypothesis ![]() is contained in an

is contained in an ![]() 1 and therefore

1 and therefore ![]() > 0. The number of all

> 0. The number of all ![]() α’s which contain

α’s which contain ![]() is equal to the number of all

is equal to the number of all ![]() α’s which contain

α’s which contain ![]()

![]() , i.e., φ

, i.e., φ![]() , α. Therefore the number of times that

, α. Therefore the number of times that ![]() is “counted” is

is “counted” is

But this number is zero, by §3, Formula 5, Q.E.D.

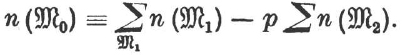

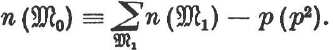

THEOREM 19: The number of subgroups of fixed order pm(0 ≤ m ≤ n) of a p-group ![]() of order pn leaves 1 as a remainder when divided by p.

of order pn leaves 1 as a remainder when divided by p.

Proof: If n = 0, then the theorem is clear. Now let n > 0 and assume that the theorem is proven for p-groups whose order is less than pn. If m = n then the theorem is trivial. Let m < n. For Theorem 19, let (![]() ) denote the set of all subgroups of

) denote the set of all subgroups of ![]() of order pm. Then:

of order pm. Then:

and by the induction hypothesis

![]()

moreover the number of all ![]() 1 is φd, d –1, therefore by §3 congruent to 1 mod p, so that

1 is φd, d –1, therefore by §3 congruent to 1 mod p, so that

![]()

follows, Q.E.D.

THEOREM 20: (Kulakoff): In a non-cyclic p-group of odd order pn, the number of subgroups of order p(0 < m < n) is congruent to 1 + p modulo p2.

In the non-cyclic group of order p2 there are p + 1 subgroups of order p. We apply induction on n and assume n > 2.

The number of all ![]() 1 is φd, d – 1, and therefore, since d > 1, is congruent to 1 + p mod p2. Let m < n-1, (

1 is φd, d – 1, and therefore, since d > 1, is congruent to 1 + p mod p2. Let m < n-1, (![]() ) be the set of all subgroups of order pm. By the Counting Principle it follows that

) be the set of all subgroups of order pm. By the Counting Principle it follows that

By Theorem 19

![]()

and by §3, 2., the number of all ![]() 2 (namely φd, d – 2) is congruent to 1 mod p. Consequently

2 (namely φd, d – 2) is congruent to 1 mod p. Consequently

For the non-cyclic ![]() by the induction hypothesis. As was shown, the number of all

by the induction hypothesis. As was shown, the number of all ![]() 1 is congruent to 1 + p(p2). If there is no cyclic subgroup of index p in

1 is congruent to 1 + p(p2). If there is no cyclic subgroup of index p in ![]() , then

, then

If ![]() contains a cyclic subgroup of index p, then the theorem follows from the solution of Exercise 2a at the end of §3.

contains a cyclic subgroup of index p, then the theorem follows from the solution of Exercise 2a at the end of §3.

THEOREM 21 (Miller): In a non-cyclic group of odd order pn, the number of cyclic subgroups of order pm (1 < m < n) is divisible by p.

Proof: If ![]() contains a cyclic subgroup of index p, then the theorem follows from the solution of Exercise 2b at the end of §3. To continue, let every subgroup of index p in

contains a cyclic subgroup of index p, then the theorem follows from the solution of Exercise 2b at the end of §3. To continue, let every subgroup of index p in ![]() be non-cyclic, m < n-1 and assume the proof has been carried out already for smaller n. Let (

be non-cyclic, m < n-1 and assume the proof has been carried out already for smaller n. Let (![]() ) be the set of cyclic subgroups of order pm. We find the congruence:

) be the set of cyclic subgroups of order pm. We find the congruence:

By the induction hypothesis each of the numbers n(![]() 1) is divisible by p, and therefore the desired number n(

1) is divisible by p, and therefore the desired number n(![]() 0) is also.

0) is also.

THEOREM 22 (Hall): The number of subgroups of index pα in ![]() is congruent to φd, d(mod pd – α + 1). The number of those subgroups which do not contain Φ(

is congruent to φd, d(mod pd – α + 1). The number of those subgroups which do not contain Φ(![]() ) is consequently divisible by pd – α + 1.

) is consequently divisible by pd – α + 1.

Proof: If d = n, then the number in question is already known to be φd, α. Let n > 1 and let the theorem be proved for smaller n. If α = 0, then the theorem is clearly true. Let α = 0, then n(![]() β) is equal to the number of all subgroups of index pα – β in

β) is equal to the number of all subgroups of index pα – β in ![]() β. Therefore n(

β. Therefore n(![]() β) = 0 if β > α; but otherwise by the induction hypothesis

β) = 0 if β > α; but otherwise by the induction hypothesis

![]()

Since ![]() and therefore by § 3

and therefore by § 3

![]()

we have

![]()

The Counting Principle now gives the congruence

But by the Counting Principle, the right side of the congruence is exactly the number of subgroups of index pα in an elementary abelian group of order pd, so that

![]()

Exercise (Kulakoff): In a non-cyclic p-group of odd order pn, the number of solutions of xpm = e(0 < m < n) is divisible by pm + 1.

Exercise: The number of normal subgroups of order pm in a group of order pn(0 < m < n) is congruent to 1 (mod p).

If p is odd, 1 < m, and ![]() is non-cyclic then, more precisely, the number is congruent to 1 + p (mod p2).

is non-cyclic then, more precisely, the number is congruent to 1 + p (mod p2).

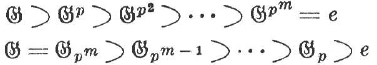

P. Hall has generalized the concept of a terminating ascending central series by defining:

A chain of normal subgroups of ![]()

![]()

is called a central chain if ![]() i/

i/![]() i + 1 is contained in the center of

i + 1 is contained in the center of ![]() /

/![]() i + 1 (i = 1, 2, … r).

i + 1 (i = 1, 2, … r).

If the ascending central series (See II § 4, 3.) terminates, then it is a central chain. The following definition is still more useful: A chain of subgroups

![]()

is said to be a central chain if the mutual commutator group (![]() ,

, ![]() i) is contained in

i) is contained in ![]() i + 1 (i = 1, …, r). Since for every xi in

i + 1 (i = 1, …, r). Since for every xi in ![]() i, x in

i, x in ![]() :

: ![]() and thus certainly xxix–1

and thus certainly xxix–1 ![]()

![]() i, it follows that

i, it follows that ![]() i is a normal subgroup of

i is a normal subgroup of ![]() and that

and that ![]() i/

i/![]() i + 1 is contained in the center of

i + 1 is contained in the center of ![]() /

/![]() i + 1. The converse is clear.

i + 1. The converse is clear. ![]() r + 1 is contained in

r + 1 is contained in ![]() 0; if it has already been shown that

0; if it has already been shown that ![]() r + 1 – i is in

r + 1 – i is in ![]() i where i < r, then

i where i < r, then

![]()

and therefore ![]() . Hence

. Hence

![]()

Consequently ![]() =

= ![]() .

.

If a group has a central chain, then it is nilpotent and the length of every central chain is at least equal to the class of the group.

Now it is natural to define the descending central series for an arbitrary group ![]() as

as ![]() where

where ![]()

![]()

If ![]() has a central chain (1) then it follows by induction that:

has a central chain (1) then it follows by induction that: ![]() and therefore

and therefore ![]() If, conversely, the descending central series is equal to e from the (r + 1)-th place on, then

If, conversely, the descending central series is equal to e from the (r + 1)-th place on, then ![]() is a central chain. If c is the class of

is a central chain. If c is the class of ![]() , then

, then ![]() and therefore

and therefore ![]()

In a nilpotent group, the class c can be found from the relation:

![]()

By Chapter II, § 6, ![]() i is a commutator form of

i is a commutator form of ![]() of weight1 i and of degree 1 and is generated by the higher commutators (G1 G2, … Gi) where Gj

of weight1 i and of degree 1 and is generated by the higher commutators (G1 G2, … Gi) where Gj ![]()

![]() . Therefore

. Therefore ![]() i is a fully invariant subgroup of

i is a fully invariant subgroup of ![]() .

.

For every subgroup ![]() of

of ![]() it follows that

it follows that

![]()

If ![]() is a normal subgroup of

is a normal subgroup of ![]() , then

, then

![]()

It follows from this that:

Every subgroup and every factor group of a nilpotent group is itself nilpotent, and the class of the subgroup or factor group is at most equal to the class of the whole group.

We wish to state something about the positional relationships, and the mutual commutator groups, of members of the descending central series and of an arbitrary central chain.

If ![]() is a sequence of subgroups of an arbitrary group

is a sequence of subgroups of an arbitrary group ![]() , so that

, so that ![]() it follows immediately that is a normal subgroup of

it follows immediately that is a normal subgroup of ![]() . If moreover

. If moreover ![]() then it follows by induction that

then it follows by induction that![]() In nilpotent groups of class c we can conclude from this that:

In nilpotent groups of class c we can conclude from this that:

(4) ![]() i is contained in

i is contained in ![]() c – i (since otherwise we would have

c – i (since otherwise we would have ![]() c = e).

c = e).

1 ![]() i is also called the i-th Reidemeister commutator group.

i is also called the i-th Reidemeister commutator group.

Now we claim that in the general case

![]()

We carry out the proof by induction on i. By hypothesis

![]()

Let i > 1 and assume we have already proven that ![]() for all k.

for all k.

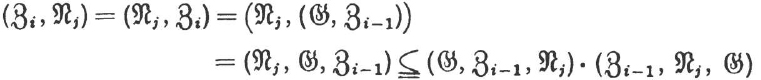

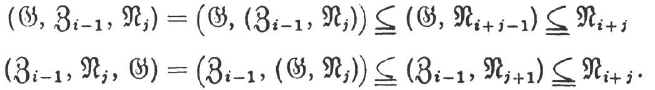

Then by II. Theorem 14:

and by the induction hypothesis:

Therefore

![]()

If we set

![]()

then

![]()

We can now show by induction on the weight that:

An arbitrary commutator form f(![]() ) of weight w is contained in

) of weight w is contained in ![]() w.

w.

This is true if w = 1. Now let w > 1, and assume that the statement is already known to be true for commutator forms with weight less than w. We have f(![]() ) = (f1(

) = (f1(![]() ), f2(

), f2(![]() )) where the fi are commutator forms of weight such that w = w1 + w2. By the induction hypothesis it follows that

)) where the fi are commutator forms of weight such that w = w1 + w2. By the induction hypothesis it follows that ![]() thus

thus

![]()

In particular it follows that

![]()

![]()

A nilpotent group of class c is always k-step metabelian, where k satisfies the inequality

![]()

Moreover if we set ![]() –1 =

–1 = ![]() –2 = … = e then in general

–2 = … = e then in general

![]()

In particular, ![]() i, commutes with

i, commutes with ![]() i elementwise.

i elementwise.

THEOREM 23 (Hall): If the non-abelian normal subgroup ![]() of the p-group

of the p-group ![]() is contained in

is contained in ![]() i, then its center is of order at least pi

i, then its center is of order at least pi ![]() itself is at least of order pi + 2, its factor commutator group is at least of order pi + 1.

itself is at least of order pi + 2, its factor commutator group is at least of order pi + 1.

Proof: Since ![]() i commutes with

i commutes with ![]() i elementwise,

i elementwise, ![]() is not contained in

is not contained in ![]() is in the center of

is in the center of ![]() and, by Theorem 14, is at least of order pi so that a fortiori the center of

and, by Theorem 14, is at least of order pi so that a fortiori the center of ![]() is of order divisible by pi + 2. Since p2/

is of order divisible by pi + 2. Since p2/![]() :

: ![]() (

(![]() ), the order of

), the order of ![]() is divisible by pi + 2. Since

is divisible by pi + 2. Since ![]() is not abelian, we can find in the normal subgroup

is not abelian, we can find in the normal subgroup ![]() ′ of

′ of ![]() a normal subgroup

a normal subgroup ![]() 1 of

1 of ![]() with

with ![]() , of index p under

, of index p under ![]() ′.

′. ![]() /

/![]() 1 is a non-abelian normal subgroup of

1 is a non-abelian normal subgroup of ![]() /

/![]() 1 and so we conclude as above that

1 and so we conclude as above that ![]() :

:![]() 1 is divisible by pi + 2. Consequently

1 is divisible by pi + 2. Consequently ![]() /

/![]() ′ has an order divisible by pi + 1, Q.E.D.

′ has an order divisible by pi + 1, Q.E.D.

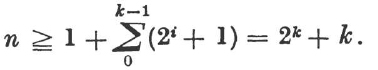

Now if in a p-group of order pn, ![]() then

then ![]() and therefore as was just shown,

and therefore as was just shown, ![]() . If

. If ![]() is now (k + 1)-step metabelian, then

is now (k + 1)-step metabelian, then

The order of a (k + 1) step metabelian p-group is divisible by p2k + k.

Remark: Under the hypothesis of Theorem 23 it can be shown by the same methods that the factor groups of the ascending and descending central series of the normal subgroup ![]() have an order divisible by pi, with the possible exception of the last factors different from 1. The proof is left to the reader.

have an order divisible by pi, with the possible exception of the last factors different from 1. The proof is left to the reader.

1. In a finite group ![]() the intersection of all the normal subgroups whose factor group is an abelian p-group is called the p-commutator group of

the intersection of all the normal subgroups whose factor group is an abelian p-group is called the p-commutator group of ![]() and is denoted by

and is denoted by ![]() ′(p).

′(p).

Prove: The p-factor commutator group ![]() /

/![]() ′(p) is an abelian p-group. Moreover, the commutator group of

′(p) is an abelian p-group. Moreover, the commutator group of ![]() is the intersection of the p-commutator groups, and the factor commutator group is isomorphic to the direct product of the p-factor commutator groups. Moreover,

is the intersection of the p-commutator groups, and the factor commutator group is isomorphic to the direct product of the p-factor commutator groups. Moreover, ![]()

2. For an arbitrary group ![]() , the class may be defined by the following property: Let the class be equal to c, if

, the class may be defined by the following property: Let the class be equal to c, if ![]() c+1 is a proper subgroup

c+1 is a proper subgroup ![]() e and

e and ![]() e + 1 =

e + 1 = ![]() e + 2 = … Let the class be equal to zero, if the group coincides with its commutator group.1 Let the class be infinite if

e + 2 = … Let the class be equal to zero, if the group coincides with its commutator group.1 Let the class be infinite if ![]() i + 1 is a proper subgroup of

i + 1 is a proper subgroup of ![]() i for all i.

i for all i.

For nilpotent groups the two definitions of class coincide.

Prove: If the class c is finite then ![]() e + 1 is the intersection of all normal subgroups with nilpotent factor group, and the factor group

e + 1 is the intersection of all normal subgroups with nilpotent factor group, and the factor group ![]() /

/![]() e + 4 is also nilpotent. Hence we shall call the factor group

e + 4 is also nilpotent. Hence we shall call the factor group ![]() /

/![]() e + 1 the maximal nilpotent factor group. Its class is c . The class of every factor group is at most c.

e + 1 the maximal nilpotent factor group. Its class is c . The class of every factor group is at most c.

If the class is infinite, then there are factor groups of any given class.

3. In finite groups of class c we can obtain ![]() e + 1 the following way:

e + 1 the following way:

For every prime number p we form the intersection ![]() p(

p(![]() ) of all normal subgroups of p-power index.

) of all normal subgroups of p-power index.

Prove: ![]() p itself is of p-power index. Hence we shall call the factor group

p itself is of p-power index. Hence we shall call the factor group ![]() /

/ ![]() p the maximal p-factor group of

p the maximal p-factor group of ![]() .

.