I have tried everything, and it’s no good.

—Attributed to Emperor Alexander Severus, c. 230 CE

Aristotle had shown how the Roman republic could save itself, or so it seemed to Cicero. Cicero had worked out the means to do it. His ideal commonwealth built on the free association of citizens inspired by great men to do great deeds would be rediscovered with delight by the buoyant age of the Renaissance and be passed along down to America’s founders.1

Cicero’s fellow Romans, however, paid no attention to his program of reform. Leading statesmen turned their backs on him. Although Cicero had held Rome’s highest office, they blocked his entry into the Senate. Men like the younger Cato, Julius Caesar, and his rivals Pompey and Crassus all knew something was seriously wrong with the Roman political system: it was suited to running a small city-state, not a vast empire. Each simply assumed he could ride out the coming chaos and emerge on top. Instead, all four would die violent deaths—while the republic itself, much as Polybius had predicted, passed into history.

As Cicero pointed out, Rome’s rot was moral and self-inflicted, and it started at the top. Julius Caesar proved that it was not just intellectuals who felt the chill of Polybius’s pronouncement of doom. He was descended from an ancient noble family, fluent in Greek, and widely read. As a young man, he set out to study the art of rhetoric on the island of Rhodes, an important center of Aristotelian learning.

On the way, however, he had been captured by pirates. By sheer force of personality, Caesar virtually took over the band of brigands. He made them applaud his speeches and admire the poems he wrote for them. After thirty-eight days his ransom was paid and the pirates released him, pledging to be friends forever. Caesar returned to Rome, raised a vigilante force of men and ships at his own expense, and sailed back to capture and crucify the pirates to the last man.

This was the kind of ruthless alpha male destined to rise to the top of Roman politics. Caesar did this in short order by crossing the Rubicon River north of Rome with his legions in order to bend the Senate to his will in 49 BCE; then by crushing his rival Pompey at the battle of Pharsalus two years later; and finally by being named dictator for life by the Senate two years after that, in 45 BCE.

It was a remarkable success, unprecedented in Roman annals. Still, Caesar suffered as much as anyone from the hole in the soul Plato and Polybius had left. There was no inward sense of triumph to match the outward of becoming sole ruler of Rome. When he stood and gazed out over the field of enemy dead at Pharsalus, which included the fine flower of Rome’s aristocracy, he said bitterly, “They would have it thus.”2 Caesar knew that his new extraordinary powers would only provoke jealousy and hatred (one of those he hoped would cooperate, Cato the Younger, chose suicide instead). He took them anyway because, “for all his genius,” as a friend later said in a striking remark, “Caesar could see no way out.”

During his dictatorship, Caesar sometimes spoke about carrying out important social reforms, especially relieving the crushing debt on Rome’s working families. In the end, he did little or nothing. As for himself, “my life has been long enough,” Caesar said at the height of his fame and adulation, “whether reckoned in years or in renown.” Victory had left the taste of ashes—and cost him a taste for living.3

On March 14, 44 BCE, Julius Caesar attended a dinner party at a friend’s house. At the height of the banquet, as the dishes were cleared away and the wine cups were refilled, the conversation turned to death.

Someone asked what kind of death would be best. Before anyone could speak, Caesar gave his answer. “An unexpected one,” he said.

The next day, on the ides of March, he got his wish.4

We don’t know if Caesar read Polybius’s Histories. We know his killer, Marcus Brutus, was steeped in it. While campaigning in Greece, he wrote a digest of Polybius’s work (now lost). He was also familiar with Cicero’s reform proposals, concocted out of Aristotle. Cicero’s own son was part of Brutus’s circle. However, as the descendant of one of Rome’s most illustrious houses, Brutus convinced himself something more drastic was needed to restore libertas as well as the mos majorum, the upright ways of Rome’s ancestors. He chose action over words, a dagger rather than a speech.

Caesar’s murder has been immortalized by Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar. This is appropriate, since the assassination was itself a piece of performance art in the tradition of Roman politics. Brutus and the other Liberators, as they dramatically called themselves, had no plans or strategy once Caesar was dead. They assumed the gesture would be enough to restore the old system. Instead, Caesar’s former allies Mark Antony and Caesar’s adopted son, Gaius Octavianus, rallied the Roman army and herded the Liberators out of the city. To paraphrase the French statesman Talleyrand, the murder of Caesar proved to be worse than a crime. It was a blunder—and the last act of the old Roman republic.

In that sense, the murder of Cicero five days later was the first act of the new Roman Empire. It came on the orders of Mark Antony, who had been the subject of some of Cicero’s most excoriating speeches (indeed, Antony demanded that the executioner bring him not just Cicero’s head, but also his hands, which had written them. With Cicero died the last hopes of a revived republic. After Brutus’s defeat at Philippi in 42 BCE, he and his fellow Liberator Cassius took their own lives. Twenty-one-year-old Octavianus, grandson of Caesar’s sister, emerged as the dictator’s heir in political as well as personal terms. His decisive victory over Egypt’s queen Cleopatra and Mark Antony at the battle of Actium in 31 BCE put the last touch on his supreme power.

Still, the decades of mob violence, gangster politics, and fashionable despair were finally over. Octavianus took the name Caesar Augustus, and the title princeps et imperator. However, Augustus was shrewd enough to see that the best way to secure his reign was to present it not as the establishment of something new, namely a Roman empire, but as the restoration of something old: Polybius’s and Cicero’s balanced constitution.

Augustus was like the architect who renovates an old apartment building by keeping the original Gilded Age façade but putting in completely brand-new fixtures. The façade included the conveniently dead figure of Cicero, who would be posthumously elevated to the status of a Roman Socrates—the virtuous man made impotent by the viciousness of his enemies, including the hated Mark Antony. It was a reputation Cicero would retain without interruption through Victorian times.

The façade also included the Roman Senate and the consulate, although the latter was now reduced to a merely ceremonial office. The new fittings included taking personal command of Rome’s legions, the largest army in the world, as imperator, or emperor—the key to stabilizing Rome all along—and taking personal control as princeps, or head of the Senate, of the provinces of Rome’s increasingly far-flung empire. The finished product, or principate, would be reviled by Romans who yearned for a return to the republic and also by some historians. But it worked. For almost three hundred years, the Augustan system maintained a solid and steady Pax Romana that protected one generation of critics after another from Rome’s enemies, even as those critics devoted their energy to trying to tear it down.

To his credit, Augustus sensed what was coming. He assembled a stable of writers, poets, and propagandists to convey the image that his principate had halted Plato’s cycle of inevitable decay and dissolution in its tracks. The poet Virgil composed an entire epic poem in the manner of Homer, the Aeneid, to persuade readers that everything in Rome’s history since its founding had been leading up to this magic moment:

Caesar Augustus, son of a god,* destined to rule

Where Saturn ruled of old in Latium, and there

Bring back an age of gold: his empire shall expand

Past Garamants and Indians to a land beyond the zodiac

And the sun’s yearly path …

To these I set no bounds, in space or time;

Unlimited power I give them.

“A great new cycle of centuries begins,” Virgil proclaimed. For Romans, “the lords of creation,” a bright new future had started.5 The problem was, no one believed him.

However, Rome’s educated elite remained plunged in gloom. “Too happy indeed, too much of a ‘Golden Age’ is this in which we are born,” wrote one with genuine bitterness.6 Augustus died in 14 CE. Literary Rome proceeded to portray his successors as corrupt and incompetent monsters, from Tiberius and Nero and Caligula to Domitian and Caracalla (the emperor who appears in all his malignant splendor in the film Gladiator). Gifted writers like Catullus and Juvenal painted imperial Rome as a cesspool of moral depravity. The image has persisted to this day. The historian Tacitus made his reputation, then and later, by tracing how the “trickle down” of corruption at the top by Tiberius, Nero, and Caligula triggered a decay of private morals and a blank passivity among Rome’s leading families in the face of tyranny.

The poet Lucan, who mourned rather than celebrated Caesar’s victory in his epic Pharsalia, wrote: “Of all the nations that endure tyranny our lot is the worst: we are ashamed of our slavery.” The satirist Propertius proclaimed that proud Rome was being destroyed by its own prosperity.

That remark is unintentionally revealing. The truth was that Augustus’s successors, even Nero and Caligula, presided over an unprecedented expansion of both the empire and its wealth. The Pax Romana protected one generation of its critics after another from the dark forces threatening the ancient world. Some of its rulers may have been mentally unstable and incompetent. In a brutal age, purges and bloodshed at the top were not unknown, and severitas was the rule more than the exception in dealing with outsiders. “You Romans bring a desolation,” Tacitus quotes one Briton complaining to his conquerors, “and call it peace.”7

All the same, what is remarkable is how this great empire managed to carry on and prosper, regardless of who was in charge. Far from being cowed by tyranny, the Roman Senate actually exercised far more power and influence than it liked to pretend. Diplomacy under Nero helped to establish peace along Rome’s frontiers; the emperors Tiberius and Claudius rendered important reforms to Roman provincial government.8 Meanwhile, the old Roman elite, having decimated itself in the civil wars of the republic, was steadily replaced by new men from the provinces, including Greece. They brought new energy and enthusiasm to the empire, just as Roman rule brought a new level of settled life to outlying areas around the world, from Britain to the desert reaches of Algeria and Mesopotamia.

The result was a strange duality in Roman culture under the empire. On one side, for three centuries legions marched, roads were built, and new provinces were conquered and plundered. Triumphs were celebrated, emperors were deified, and great temples were consecrated in their memory. Great monuments like the Colosseum and the Circus Maximus rose on the Roman skyline, as the empire’s citizens enjoyed an unparalleled prosperity and splendor. Yet Rome’s finest minds and spirits found it all empty and meaningless, even a sign of approaching doom.

A later age would develop a term for this disaffection: alienation.

But we can find its origin in Plato’s cave, when we realize all we do and see is a meaningless illusion, and we seem permanently shut out from the light and truth. Alienatio mentis became almost the occupational disease of Rome’s intelligentsia. In any case, Tacitus, Rome’s greatest historian, certainly suffered from it. He despised the imperial system even though he was writing under what posterity recognized as one of Rome’s best and most enlightened rulers, the emperor Trajan. Tacitus had to admit, “The interests of peace require the rule of one man,” and since Augustus, “all preferred the safety of the present to the dangers of the past.” Still, as historian M. L. Clarke puts it, Tacitus’s head was with the empire, but his heart was with the republic.9 He could not shake off the feeling that the reign of Augustus’s successors, which he savagely chronicled in his most widely read work, the Annals,† was only symptomatic of a deeper loss of Roman moral integrity and vitality. It was not just Caligula and Nero who were cruel and corrupt. The decay had infected all of Roman society.

In Tacitus’s eyes, the only place where you could find courage, manliness, and honor anymore was not in the Roman Empire, but on the other side of its frontiers. The naked, blue-painted natives of far-off Britain (Tacitus’s father-in-law had been governor there) and the Germanic tribes that crowded close to the Roman watchtowers along the Rhine seemed to Tacitus to display the kind of free manly virtues Romans once had and had lost.

The shame was that the Britons and Germans didn’t realize they had it so good. When they began to adopt Roman ways, like going to the baths and building villas and attending dinner parties, Tacitus sneered, “they call it civilization when in fact it is only slavery.”10

Tacitus is the first romantic anthropologist. His sentiments will reappear in the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau on the “noble savage,” among other places. But its roots are to be found once again in Plato and his Myth of Atlantis: the idea that at some primeval stage of humanity, long before the cycle of man’s degeneration began, men knew the truth clear and pure and obeyed the laws of God.

Atlantis’s inhabitants were such a people, Plato writes. But “when the divine element in them became weakened,” Plato says in the Timaeus, the former super-race of Atlantis became merely human. “To the perceptive eye,” Plato wrote in the Timaeus, “the depth of their degeneration was clear enough, but to those whose judgement of true happiness is defective they seemed, in their pursuit of unbridled ambition and power, to be at the height of their fame and fortune.”11 Zeus and the gods knew the truth, Plato says; and together they plotted the doom of Atlantis—a doom so devastating it vanished forever.

Once men knew the truth; one day they might know it again. But not before the cycle of decay and dissolution was complete, and not before existing institutions had dissolved away into nothingness.

It was precisely that nothingness which more and more Romans were yearning for.

By the time Tacitus died around 117 CE, the Roman Empire bore little resemblance to the one Polybius had known. It covered more than 2.5 million square miles from the Grampian Hills of Scotland to the Tigris and Euphrates and contained 65 million inhabitants. A network of 50,000 miles of stone-laid roads connected its most distant frontiers to its capital. It was also thoroughly Hellenized. Trajan’s successor, the emperor Hadrian, had been born in the Roman province of Spain but preferred speaking Greek to Latin. His boyhood nickname was “the little Greek,” and he became an honorary citizen of Athens. Emperors after Hadrian did most of their correspondence in Greek; Marcus Aurelius would even write his memoirs in Greek.

The migration of Greek families and Hellenized Asians into the Roman Senate that began under Augustus was now a tidal wave. Indeed, Rome could not have managed without them. Imperial Rome’s finest physicians were Greeks like Galen, who explained the functions of the human body, and Asclepiades (c.124–40 BCE) the mysteries of the human mind. The Greek Strabo established its map of the world while Ptolemy explained the movements of the stars and heavens. The famous jurists Papinian and Ulpian, who codified Rome’s laws, were also born and bred Greeks.

Alexandria, Cleopatra’s former capital, was fast becoming the intellectual center of the Roman world much as it had been the center of the Hellenistic one. The very fact that the great battles that decided the birth of the empire, from Pharsalus to Philippi to Actium, were all fought in Greece was proof that a shift of the center of gravity had been under way for more than a century—a shift that the building of a new imperial capital at Constantinople in 323 CE made official.

The presence of Greek thought and philosophy in Roman culture was more palpable than ever. Plato’s dialogues and Aristotle’s treatises, plus the innumerable commentaries on their works by generations of students, were part of the fabric of daily intellectual life. The graduates of Plato’s Academy remained active all through the empire, as were their Stoic, Epicurean, and Skeptic rivals; while the traditions of Aristotle’s Lyceum lived on in a multitude of scholars’ studies and laboratories, including Alexandria’s restored Library and Museum.

All the same, the trend was a self-defeating one. Even as the city by the Tiber crowned herself “mistress of the world,” the hole in the Roman soul yawned even wider. Under the dual impress of Plato and Polybius, all Greek philosophy managed to do was convince generations of Romans that the happiness of the human spirit depended on being indifferent to everything that their reality offered.12 Epicureans taught that men were happiest when they moved through the world like random atoms, just as the world itself was only a heap of atoms that had come together by chance, with no deeper meaning or purpose. The Skeptics (or Pyrrhonists) taught “that which is truly good is unknowable,” and since we have no means of knowing which of our judgments about the world are true and which are false, “therefore we should not rely upon them but be without judgements”—the perfect formula for a moral relativism that knows no bottom.13

The Stoics should have done better. They had understood that men and women had to live in the world, and came equipped, as Aristotle would have pointed out, with the moral and mental tools to deal with that fact. Man’s reason gives him the power to shape nature according to his needs, Polybius’s friend Panaetius the Stoic had told his patrons. The arts of civilized life, including building, tools, machines, and farming, were proof that humans were destined to build a future for themselves based on benevolent interdependence with others, under the protection of a divine providence.14

This softer, socially optimistic side of Stoicism made a deep impression on Cicero’s On Moral Obligations, where it mixed easily with Aristotelian notions of man as “political animal,” in other words born with an instinct to cooperate with others to achieve a common good.‡

All the same, it is the “hard” side of Stoicism that dominated the life and work of its most famous Roman exponent, the philosopher Seneca (4 BCE–65 CE). Seneca’s wise man is indifferent to pain and suffering; he has no fears and no hopes. He never gets angry, even when he sees his father killed and his mother raped.15 Seneca believed in humane virtues like gratitude and clemency, including toward slaves, and writes eloquently about their lasting benefit to others.

In the end, however, Seneca loved humanity more than he cared for human beings. He preached abstinence even while he owned one of the most sumptuous homes in Rome. Once, he attended the spectacles in the arena of which the Romans took great pride, with its gladiatorial combats and slaughter of wild beasts. He came back, he said, a worse person, because he had been among his fellow men. Roman society itself, he concluded, was nothing more than a collection of wild beasts.16

The characters in Seneca’s plays, which resemble The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in their taste for blood and horror, suffer unspeakable torments. However, the characters learn to bear their suffering with what Seneca called fortitudo and constantia, or constancy. They prefer to endure the “slings and arrows of outrageous Fortune,” in the words of Shakespeare (whose tragedies were heavily shaped by Seneca’s), rather than try to fight back.

Seneca’s solution to life’s inevitable cruelties was to withdraw. It was an increasingly attractive reaction in the later imperial age. The wise man must shun unnecessary human contact and connections, Seneca said. He must live within, and for, himself. He must cultivate the virtue of apatheia, literally an indifference to the fate of others—apathy even, in the last moment, to his own fate (faced by unjust accusations by the emperor Nero, Seneca and his wife chose suicide).17

Remain indifferent to pain and accept your fate. Consider yourself already dead, and live out the rest of your life according to nature. These Stoic lessons also fill the pages of Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, written a century after Seneca’s death and the one piece of serious philosophy to come from the pen of a Roman emperor.

From the watchtowers of Hadrian’s Wall in northern England, and the army camps along the Rhine and Danube frontiers, Marcus Aurelius could see the forces of barbarian darkness already gathering. He would spend his reign fighting to shore up the frontiers from attack, from the Germanic tribes in the north to the Parthians in the east. He would die on campaign along the Danube in 180 CE, worn out and without hope.

The Meditations were probably written during the bloody wars of the 170s, when it really did seem as if Rome might not survive. However, they tell us nothing about the tumultuous events taking place outside the emperor’s tent. Instead, they reflect a resigned state of mind that is influenced not only by Stoicism, but by the figure of Socrates. Socrates was a particular hero for Marcus Aurelius, as the man who accepts his mortal fate; a symbol of a philosophy that is indeed a “meditation on death.”

What are Alexander and Pompey and Augustus, Marcus Aurelius asks, compared with Socrates and Diogenes and Heraclitus—the man who said that nothing in the world is permanent? “This is the chief thing: be not perturbed, for all things are according to the nature of the Universal; and in a little time you will be nobody and nowhere.…” So leave this life satisfied, because He who releases you is also satisfied.18

Strange words to come from a man who was ruler of the known world. Socrates, Plato, Diogenes, and even Pythagoras appear several times in the Meditations. Aristotle, never. Aristotle’s outlook was precisely the one Marcus Aurelius wanted to warn against: the idea that man is born to take charge of his existence and solve problems in a practical way, by building a better house or a more efficient machine; to make a better empire and a better life. Man’s impulse toward energeia, considered action toward a desired end, was precisely the way of life the Meditations rejected.

“You have been a citizen of this great world,” Marcus Aurelius says to himself in his last meditation. “What difference does it make if it is for five years or one hundred?” Of course, for millions it was a very great matter. Sixty years after Marcus Aurelius’s death, from 245 to 270, every Roman frontier collapsed.19 For those who lived through it, the Stoic message of “bear and forbear” was very cold comfort. However, another thinker arose who would offer comfort, at least to those who had time and energy to devote to books and philosophy. He showed men that if they could not control the great disasters of the third century, they could rise above them. And if they could not save the empire, they could at least save their souls.

His name was Plotinus. He is without doubt the most important and influential thinker to appear between Aristotle and Saint Augustine. Yet we know almost nothing about him. His life is an enigma wrapped in a mystery. He declined to tell his disciples any details about his life. He even refused to have his portrait painted or a bust made of his likeness.

Plotinus was also the most relentlessly antimaterialist thinker in history. He taught his disciples that everything we see or imagine to be real is actually only a series of faded images of a higher realm of pure ideas and pure spirit, intelligible only to the soul. According to his student Porphyry of Tyre, he was even sorry that his soul had to live inside a physical body.20

That sounds a great deal like Plato, and Plato was always the central figure in Plotinus’s cosmic vision. But Plotinus had also read his Aristotle, and by putting the two together in a thoroughly original way, he transcended the traditional limits of ancient thought. It was a major breakthrough. From the last days of the Roman Empire through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Plotinus’s “Neoplatonism” offered a new dimension for the European intellect to explore, and a new challenge: how to make the rational soul one with the Absolute.

Plotinus appears to have been born in Lyco in Egypt, a city that was founded on the Lower Nile by priests of Osiris, probably around 205. Whether Plotinus had any family connection with the rites of Osiris, the Egyptian god symbolizing man’s hope for immortality, we will never know.21 When he came to Alexandria to study at age twenty-eight, his interests were not religious at all but philosophical. He set up with a teacher, Ammonius Saccas, who immersed him in Plato and also Aristotle.§

Later Plotinus became part of Emperor Gordian III’s entourage on his disastrous expedition against the Persians in 238. Gordian’s army suffered a crushing defeat; the survivors scattered in all directions, while the hapless Gordian, still in his teens, was murdered by his courtiers. Among the refugees was Plotinus, who found shelter first in Antioch and then in Alexandria. The whole experience must have confirmed Plotinus’s conviction that what we call “real life” is actually a realm of meaningless pointless suffering. Still, Plotinus refused to surrender to the usual Roman impulse toward bitter alienation. Instead he decided he was going to set up a school of philosophy to examine the alternatives—this time not in Alexandria or in Athens, but in Rome itself.

It was a momentous decision—and symbolic of a momentous break. What Plato’s Academy had done in the nearly five centuries since Plato’s death held no interest to Plotinus. He and his followers always called themselves “Platonists,” never “Academics.”22 The long tussles between the Academy and the Epicureans, Stoics, and others had led the formal heirs to Plato further and further away from Plato’s original ideas and doctrines. Now Plotinus brought them back to where they were supposed to start: the dialogues, including the Timaeus, which Plotinus read not just as a handbook for understanding astronomy or physics, as Cicero and others had, but as the key for understanding existence itself.

Since Socrates, thinkers had been obsessed with the question “What is the good life?” Plotinus decided it was time to revert to the earlier question, “What is reality?” What he discovered is that once we get the right answer to that question, it also provides the key to the other one. In other words, no truly virtuous or happy life is possible until we realize that everything, including ourselves, has its rightful place in a single spiritual realm: the Absolute One, Goodness or Being in Itself.

This may sound like Plato, but then Plotinus veers in a very different direction. Plato had seen reality as dual, with the spiritual and the material as totally separate and distinct realms. Plotinus wanted to treat them as a single totality, embracing Being in Itself and the smallest and most insignificant part of creation and everything else in between.

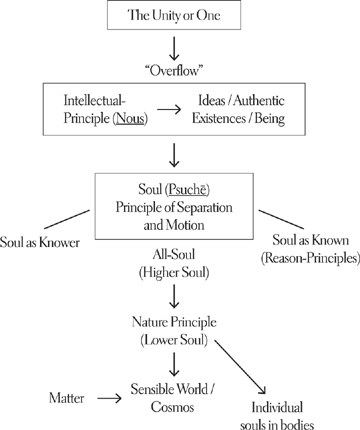

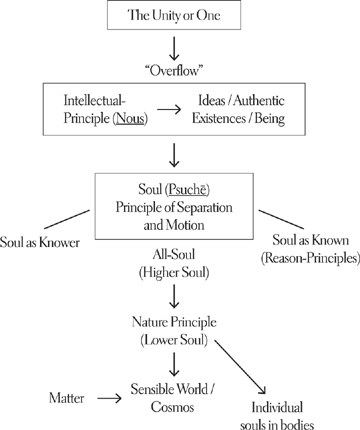

Plotinus’s universe doesn’t just exist. Like Aristotle’s, it forms a living system, a continuous spiritual emanation from the Being in Itself’s own perfection, like water cascading down the steps of an enormous pyramid or ziggurat. Its life-giving force flows down the steps, level by level, and then spreads across the rest of creation. Plotinus taught that the material world is not distinct from the spiritual. The cave still reflects the distant light of truth, no matter how dimly.

Instead, all things exist in a carefully ordered sequence, a sequence not only of time but of value, running from the purest and most spiritual—the One and its animating principle, Nous, or Being in Itself—down to the basest and most material, just as the steps of the ziggurat lead from one to the next.

Where did Plotinus get this idea? Obviously it comes from Plato and his vision of the Good in Itself, which not only is the summit of all knowable things, but also gives the rest of the Forms (and everything else knowable by reason) their very existence.23 But it also owes a debt to Aristotle’s Metaphysics. Plotinus saw at once that Aristotle had provided him with a built-in scale for ordering all reality. At the top sits pure Form, Aristotle’s invisible Prime Mover. Then comes the visible but imperishable realm of the planets and heavens. Next comes the realm of substances, informed matter, starting with man, then animate animals and inanimate plants, followed by the inorganic world of rocks, dirt, and water, as Aristotle’s life-giving, purpose-giving form gradually loses out to matter.

Finally, at the bottom, Aristotle put Prime Matter itself: without form, unlimited, and without extension, with no positive properties.24 Like pure Form, it is invisible to the human eye, but it remains a necessary component for everything sandwiched in between.

So far so good, if you are an orthodox follower of Aristotle. But Plotinus now put this together with Plato’s picture of God the Demiurge from the Timaeus, the Supreme Creator who crafts the universe out of the image of His own perfection, so that each element reflects the perfection of the whole. All of a sudden, Plotinus gave his generation a whole new luminous way of seeing the world and humanity’s place in it.

To understand its impact, we need to go back on our first Aristotelian walk through the woods but this time see it through Plotinus’s eyes. We see the same trees and shrubs and stones in the path and the clouds overhead, we hear the same creatures scurrying in the leaves and insects buzzing around our head, and we feel the same sun on our face and the same breeze blowing through our hair.

But now we see that everything expresses, to an exact lesser or greater degree, the animating life-giving spirit of mind and Being, which connects everything to everything else. From God Himself in the heavens and the sun in the sky, to me and Rover the chocolate Lab with his humanlike alertness and curiosity, the watchful deer in the shadows, the chipmunks and squirrels, the bees and other insects, and then the trees and other flora, down to the dirt and dead leaves: All form an ordered hierarchy of Being.

I curl a baby lizard in my hand, so transparently orange that it seems made of plastic. But then it moves, its tiny limbs reminding me that it carries the breath of divinity within it, less than that of my own soul but more than the twigs and leaves from which I extracted it—and all in harmonious proportion with one another. When the eighteenth-century poet William Blake spoke of seeing eternity in a grain of sand, he was speaking the language of Plotinus and Neoplatonism.

“All things follow in continuous succession,” Plotinus told his disciples, “from the Supreme God to the last dregs of things, mutually linked together and without a break.” At the top is the One and the Good, beyond knowledge and description. “As the One it is the first cause, and as the Good the last end, of all that is.”25 As part of its own perfection, the One produces Nous, or Being in Itself, which contains all the perfect intelligible forms necessary for creation. Nous in turn gives birth to the World Soul, just as in Plato’s Timaeus: it is both the generator and the container of the rest of creation, the means by which life flows out into the rest of existence, including the human soul, our direct point of contact with the source of all goodness and perfection.

The One’s spiritual giving does not stop there. It flows down uninterrupted through the animals and plants, down to the smallest speck of dust and least significant bits of matter, all of which still reflect to some infinitesimal degree the perfection of the whole. From one end to the other of the hierarchy, everything participates in a constant diminishing series of divine emanations.

These emanations, and the connections they forge, form what comes to be called the Great Chain of Being. Any time a thinker of the Middle Ages or Renaissance talks about “a scale of being” or “the ladder of perfection,” he is borrowing from Plotinus.26 And just as all things spiritual and material form rungs along the ladder, so God “fills them all with life … this single radiance [which] illumines all and is reflected in each, as a single face might be reflected in a series of mirrors.”27

The cosmos according to Plotinus

In his search for an ordered intelligible guide to existence, Plotinus had managed to fuse Aristotle’s regard for the material world as the work yard of form with Plato’s Demiurge as the procreative fountainhead of all truth. Yes, Plotinus says, we are born in a cave. But it’s not hard to find our way out. There’s a trail provided for us, because the links in the Chain of Being not only go down, like the steps of a ziggurat, they also lead up. The downward flow of divine perfection is matched by an equal upward striving of all things back toward their original source.

The human soul, which bears the largest share of that spiritual radiance that fills all material creation, feels that upward tug the most. We don’t have to be dragged forcibly out of the cave to see the light, either, as Socrates seemed to suggest in the Republic. Instead we are gently pulled out by our own innate attraction to perfection: because that perfection is our own true self.

This would be Plotinus’s great message to his own age and to the future. All of us, whether we know it or not, want to be one with perfection—or as later Neoplatonists will say, to be one with God. No one wants to live in the cave. We all want to see the light; and once we discover the true trail, we can retrace the path of the spirit back to whence it came.

Of course, finding the trail is the great difficulty. That is why Plotinus set up his famous school in Rome. For a time, it was more famous than the Academy. Plotinus resided in a Roman mansion belonging to two rich aristocratic women, mother and daughter, both called Gemina. There he drew to himself a circle of senators, doctors, well-to-do students, and literary types with whom he conducted a nonstop seminar in the manner of Plato’s dialectic.

The discussions seem to have gone on for days. They also—and this was unique in Greek or Roman philosophical circles—included women students and children (indeed, a number of distinguished Roman families made Plotinus their children’s guardian). His students were part of a last despairing generation of Romans. They desperately wanted answers. As the emperor Alexander Severus (who was an avid fan of Plato’s Republic) said, they had tried everything else and had found it was a waste of time. So they looked to their teacher, Plotinus, their guru almost, to explain how to find their way back to truth and spiritual health.

He, on the other hand, was content to take his time. As we know from the Enneads, the discussions ground on day after day, topic after topic. Increasingly, Plotinus realized that no dialectical process, no matter how rigorous, was going to lead to the big breakthrough he wanted: to see the truth for itself and grasp the last mysteries of existence.

Plato had written about the inadequacy of mere words to express reality—one reason he often turned to myth and allegory.28 The Pythagorean alternative had been to turn to the eternal truths of number and mathematics. But to Plotinus mathematical reasoning, too, seemed a series of clumsy symbols or signs, just as language did, compared with the raw truth of spirit and the One.

The trail out of the cave suddenly seemed a dead end. Plotinus decided there was only one way out: a leap of mystical illumination.

According to his student Porphyry of Tyre, Plotinus experienced this mystical union at least four times in the six years Porphyry studied with him. Plotinus’s description of what it was like stretched the normal boundaries of language—proving again to Plotinus the inadequacy of words to capture the most essential features of reality.

“Often I have woken to myself out of the body,” Plotinus wrote, “[I] had become detached from everything else and entered into myself.” Plotinus found himself surrounded by “beauty of surpassing greatness” and felt assured that “I belonged to the higher reality,” which lay beyond the realm of Intellect and belonged directly with the Divine.29

In the end, Plotinus’s system is less of a philosophy than a religion.30 At its core is a mystical, even ecstatic, union with God, the final leap in which we transcend all the limitations of matter, time, and space and become one with the One. The closest metaphor Plotinus could find to capture its delight was of a dance with eternity:

On looking on [the One] we find our goal and our resting-place, and around Him we dance the true dance, God-inspired, no longer discordant.… In this dance, the soul beholds the wellspring of Life, and wellspring of Intellect, the source of Being, [the] cause of Good, and root of Soul.…

In the divine dance, these highest spiritual qualities appear in themselves, undiluted by their presence in material creation. “They themselves remain, like the light while the sun shines.”31

For Plotinus, the task of the wise man is the same as it was for Socrates. It is to prepare the soul for the final revelation of truth. But no one has to wait to die to achieve it. Wisdom can be found here and now, through mystical union with the One that takes us “from this world’s ways and things” to a higher reality.

All around him and his school, the Roman Empire was steadily coming apart. Plotinus ignored it. He proposed to the emperor Philip creating a new city to be called Platonopolis, where Plotinus and other philosophers could find peace and shelter and study the nature of the universe. Unlike Plato’s original version in the Republic, this utopian city would be set up not to remake the world, but to escape from it.

Philip listened politely, but nothing came of the plans. With Germans streaming across the Rhine, Goths plundering cities in Greece, and the Parthians hammering away from the east, the emperor had other things to worry about. With Plotinus we have come to the last loosening of the ties of loyalty between the empire and its best and brightest. “The wise man,” Plotinus said, “will attach no importance to the loss of his country.”32 True happiness (eudaimonia) requires a flight from all worldly connections toward a higher end, the final union of the soul with God.

Plotinus had finally found the cure for the hole in the soul of his world-weary countrymen. The price was any commitment to, or belief in, the value of the Roman Empire or any other kind of politics. Don’t worry about those things, Plotinus said. Stay on the steep ascent to the One, and keep the soul focused on its ultimate goal. On his deathbed his last words were, “Strive to lead back the God within you to the Divine in the universe.”33

There was only one problem. Plotinus’s solution worked fine for those with the money and leisure to retire to a Roman villa to contemplate the eternal verities. What about everyone else?

Strangely enough, the answer lay just outside Plotinus’s door.

* That is, since he had defied Julius Caesar and built a temple to his memory.

† They would inspire Robert Graves’s I, Claudius, with their picture of Rome at its most vicious and X-rated.

‡ Similarly, the Stoic notion that all men are brothers because they share the same nature (logos) paid huge dividends in the development of Roman law and of how basic principles of justice can have universal application to all peoples everywhere—a development that is still going on in international law today.

§ Another student of Ammonius Saccas was a sharp-eyed, intense young man named Origen, who would use his master’s lessons very differently. See chapter 10.