The transition between war and peace was to be a prolonged one. This early 1950s advertisement for Ryders’ seeds still gave prominence to vegetables over flowers.

AS THE LONGED-FOR peace became more of a future reality than a far-off dream, so the victory diggers of England started to pause in their efforts. By 1943, when Lord Woolton was rather optimistically appointed Minister of Reconstruction, many gardeners were impatient to abandon the vegetable plot and reconstruct their flower borders. In July 1942 Cecil Middleton and his listeners took it for granted that he would talk about ‘leeks, lettuces, and leather-jackets’, rather than ‘lilac, lilies, and lavender’, but in February 1944 – with VE Day still fifteen months away – he was forced to try and bring them back to the Dig for Victory fold. ‘There is nothing’, he said, ‘I would like better than to put my lawn down again and to refurnish the borders; I should just love to cut bunches of roses and lilac and herbaceous flowers again, but the time is not yet. The need for growing food at home is as great, if not greater, than at any time during the war, and we must not relax for a moment, rather should we make still greater efforts for we may yet know what it is to be hungry.’

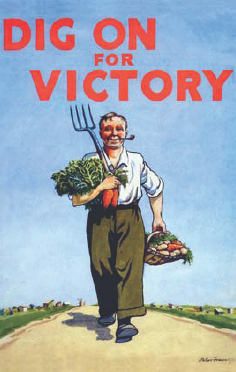

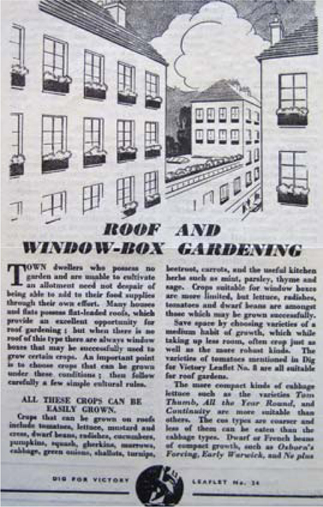

In 1944 a ‘Gallup’ poll by the British Institute of Public Opinion indicated that over 50 per cent of people assumed that once peace was declared rationing would ease and food supplies would flow in from pre-war supply lines again. Allotment take-up began to slump, and in response the government, headed by the Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Information, launched new advertising campaigns. At the opening of every Dig for Victory show in the summer of 1944 a telegram from the Minister of Agriculture was read out to further encourage efforts: ‘We have, in the last five years, achieved on the garden and allotment fronts a great deal of which we can be proud. But the war is not yet won, and even when the Nazi gangsters are beaten, food will be scarce. Perhaps scarcer than now. So carry on – do not rest on your spades, except for those brief periods which are every gardener’s privilege.’ New slogans and new posters were tried out, including ‘Dig On for Victory’, ‘Dig to Keep Well Fed’ and ‘The need is GROWING’. A short campaign saw ‘old hands’ encouraged to provide advice and encouragement to new diggers, and planning for the future was the new theme. ‘You Need A Plan’ and ‘Better Planning, Better Gardening, Better Crops’ sparked applications for the constantly reissued Planning a Plot Dig for Victory leaflets. For those who still did not have access to an allotment, Dig for Victory Leaflet No. 24 was on the subject of Roof and Window-box Gardening, and the Ministry of Agriculture’s warning that ‘we shall have to maintain Home Food Production to the utmost into the post-war years’ might have encouraged windows everywhere to be decorated with lettuces.

‘Dig On for Victory’, ‘Dig for Plenty’ and ‘Dig for Peace’ were all phrases used in the final year of the war.

The removal of park railings in Britain (for their metal content) had brought into sharp focus the worth of humble vegetables, as they became increasingly subject to theft. Stealing from wartime vegetable gardens was classed as ‘looting’, and could result in a heavy fine or even a prison term. Onions were the most common casualties of theft as they have to be left on the surface to dry out once harvested, but leeks and other above-ground vegetables suffered as rationing became tighter.

If the situation was difficult in Britain, it was worse in much of occupied Europe. By the end of 1945 the scheme of allotments and home food producers was in use across mainland Europe to try to stave off a humanitarian disaster. In Germany food rations had been severely cut since the winter of 1944, and, with the collapse of the Nazi regime and the destruction of transport links, the winter of 1946–7 was to become known as the ‘Hunger Winter’. The Royal Horticultural Society sent its popular image-based The Vegetable Garden Displayed into Germany but by the spring of 1946 it was estimated that calorific provision in the British-occupied zone fell as low as 1,050 calories a day. In Moscow, over 1.5 million people turned 35,000 acres into allotments and Victory Gardens, while across the Soviet Union as a whole 11.5 million people cultivated plots.

One of the last Dig for Victory leaflets to be issued appealed to those who really did not have any garden space!

Commencing in January 1945, the year that was finally to see both victory in Europe and victory over Japan, the government brought out its own monthly Allotment & Garden Guides. The guides eschewed such fripperies as flowers and concentrated on ‘helping you get better results from your vegetable plot and fruit garden’. Providing an overview of what needed doing that month, what should have been done the previous month, and the ideal of planning ahead for the next month, the guides carried the unwelcome message that ‘this will be the tightest of the war years so far as food supplies are concerned’ and that only those who did not ‘rest on their spades’ would be able to provide for their families. As demobilsation started, and rationing tightened (with bread being rationed for the first time from July 1946), the 1943 prophecy by Robert Hudson (Minister for Agriculture) that ‘When the day of victory dawns the need for the little man and his wife to go on producing their own food will be just as pressing’ was fulfilled.

With the end of the war, public parks and private land that had been requisitioned for the provision of allotments were returned to their original purposes, often with only a few months warning for the irate allotment holders. Allotment numbers fell rapidly from 1.5 million to around 500,000 in the following decades. After the First World War an almost immediate decline in allotment numbers had conflicted with increased demand by returning servicemen facing economic depression, but after five years of war on the Garden Front many allotment holders had had enough by 1946. In an attempt to keep up interest even the Allotment & Garden Guides had to admit that a ‘happy fringe of flowers’ around the edge of an allotment was allowable, although any more than 10 per cent of a plot devoted to flowers on a plot merited an inquisition by the local allotment association.

Allotment & Garden Guides were published every month through 1945. The request to ‘Please Keep’ hinted not only at economy but that they would be needed in future years.

The winter of 1946–7 was one of the worst on record, with large swathes of the country enveloped in fog and snow from 21 January to 16 March 1947. Root vegetables were impossible to extract from frozen ground, and even winter cabbage, leeks and Brussels sprouts suffered under the extreme conditions. For the plant nurseries battling to recover from the wartime restrictions this was a final blow. Plants that had survived the war suffered in the freeze, and many businesses were forced to rebuild their stock from European and American nurseries. In 1948 the charismatic Harry Wheatcroft imported a peachy-yellow standard rose that was to repopulate the gardens of the post-war suburbs; he called it ‘Peace’.