The Support Weapons

A major blunder was Rhodesia’s failure to invest in the production of ammunition even though it possessed an iron and steel industry and associated enterprises. Instead it had to purchase ammunition with some difficulty from abroad, with South Africa being the main supplier. It was a mistake to be utterly dependent on external sources as events in 1976 proved when the South African Prime Minister, B. J. Vorster, twisted Smith’s arm by withholding ammunition and fuel.

Although nothing was done to rectify this mistake, the Rhodesians did exploit their possession of a factory making nitrogenous fertilizer which provided a basic ingredient for the common high explosive, ANFO, which is used in the mining industry. The ingredients are ammonium nitrate pellets mixed with diesel which, when detonated, result in a high-velocity explosion. Thus ANFO allowed the local production of a singularly lethal range of bombs designed not only to improve the striking power of the jet aircraft but also those of the light aircraft such as the Cessna 377 Lynxes.

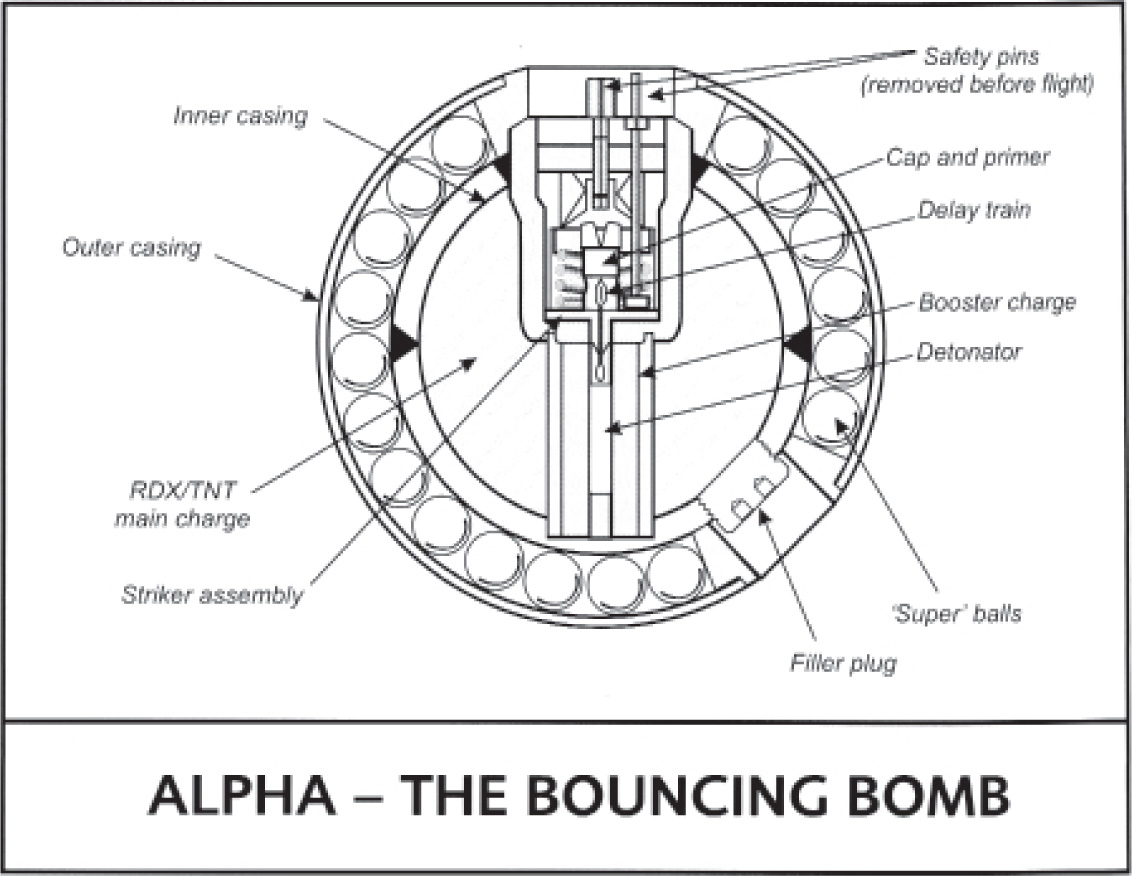

The Mk II or ‘Alpha’ bomb (as the first in the range of new projects) was designed to replace the Mk1 20lb bomb. The Mk1 had been withdrawn from service with the Canberra after several had detonated prematurely on 4 April 1974, destroying Canberra No. 2155, and killing Air Sub-Lieutenants Keith Goddard and Richard Airey, her pilot and navigator. Intended for conventional warfare in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the Canberra was designed to carry the 250, 500 and 1,000lb range of bombs to attack hard targets like bridges, bunkers and buildings. To arm the Canberra for the counter-insurgency warfare, and particularly attacks on concentrations of insurgents, the Rhodesians had adopted the locally produced Mk I 20lb wire-bound fragmentation bomb with a proximity fuse which detonated it close to the ground. The Rhodesian Air Force’s drawing office designed an aluminium bomb box to allow a Canberra to carry 96 Mk Is in its bomb bay to achieve the saturation of a target. There were three problems, however. The first was that accurate delivery required flying at a low altitude but, to avoid damage from its own bombs, the aircraft could not go lower than 1,500 feet above ground, the perfect height for the Strela missiles and within the range of the anti-aircraft guns possessed by the insurgents. The second was that the bomb pattern was a line of small bombs running through a target and not smothering it. The third problem was that the Mk I bombs on release could jostle together in the turbulent air stream within the opened bomb bay and, with armed proximity fuses, explode prematurely. The midair explosion on 4 April 1974 had not only killed Goddard and Airey but had robbed No. 5 Squadron of a role because there were few targets for its heavy bombs.

The challenge of returning the Canberra to the front line of the growing counter-insurgency effort was taken up by Group Captain Peter Petter-Bowyer when directing projects in early 1976 in collaboration with Squadron Leader Ron Dyer, the Senior Officer Air Armaments. Because the range of conventional bombs in stock was having a limited effect as too much of the blast and shrapnel was projected harmlessly upwards, Petter-Bowyer proposed saturating a target with small spherical bouncing bombs. He did so after reading of the use of hundreds of steel balls dropped from speeding United States Air Force jet fighters to shred the jungle in Vietnam. He understood that, to be effective and to achieve a concentrated spread, the proposed bombs had to be delivered at a height of less than 500 feet above ground at over 250 knots. An advantage of this was that the aircraft would be too close for a Strela missile to arm while presenting a fleeting target to the opposition’s machine guns. In addition, the high air resistance of a round bomb would slow it sufficiently to allow it to explode well behind the bomber. A cluster of round bombs, affected by each other’s turbulent, tumbling slipstream, would spread laterally to smother a wide area.

The invention and manufacture of the prototype of the small round Mk2 ‘Alpha’ bomb (‘Alpha’ being the first in the range of new projects) and its acceptance took just three weeks in early 1976 and another four weeks for it to be ready for operational use. As part of Petter-Bowyer’s team, a local engineering firm, Cochrane & Son, produced the casing leaving the technicians of the Rhodesian Air Force’s small armament section to fill the bombs—bomb-filling being a task that no other air force required of its staff. The bomb was double-hulled with the outer 155mm-diameter steel casing lined with 250 super-rubber balls between it and the inner 87mmdiameter steel sphere filled with RDX-TNT explosive. The optimum bombing height and speed was 300 feet above the ground at 350 knots. This spread the bombs which on impact bounced forward across the area. After 0.7 seconds of forward flight, an ingenious three-way detonating pistol exploded the bomb at a height between two and five metres. Forty-five per cent of the casing—against seven and a half per cent of the conventional antipersonnel bomb—would saturate the target. Although the detonator would be triggered regardless of whatever part of the outer casing hit the ground, it was not so sensitive that collisions in mid-air with another bomb or the accidental dropping by a handler would not set it off. To provide multiple airbursts over a wide area, 300 bombs would be carried in six specially designed hoppers fitted in a Canberra bomb-bay. As each hopper carried 50 bombs, the Canberra’s crew had the choice of dropping one hopper-load or a series of them (with a 0.6 second delay between each release) or all at once. Again the Air Force’s technical staff were involved as the hoppers were designed by the Drawing Office, headed by John Cubitt, and made in the Thornhill Station workshops. Spraying outwards, 300 bombs would devastate an area of 100 metres wide and 700 metres long. These bombs were particularly feared by ZANLA and ZIPRA and would wreak fearful damage on insurgent concentrations.46

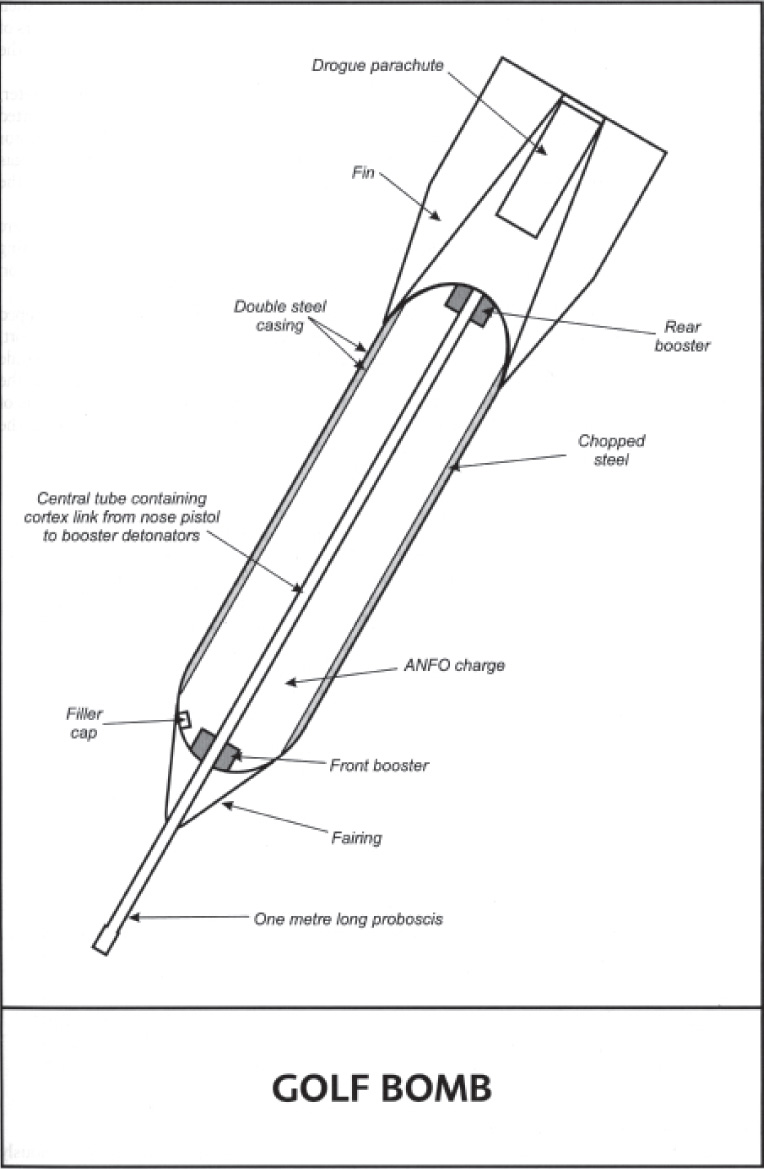

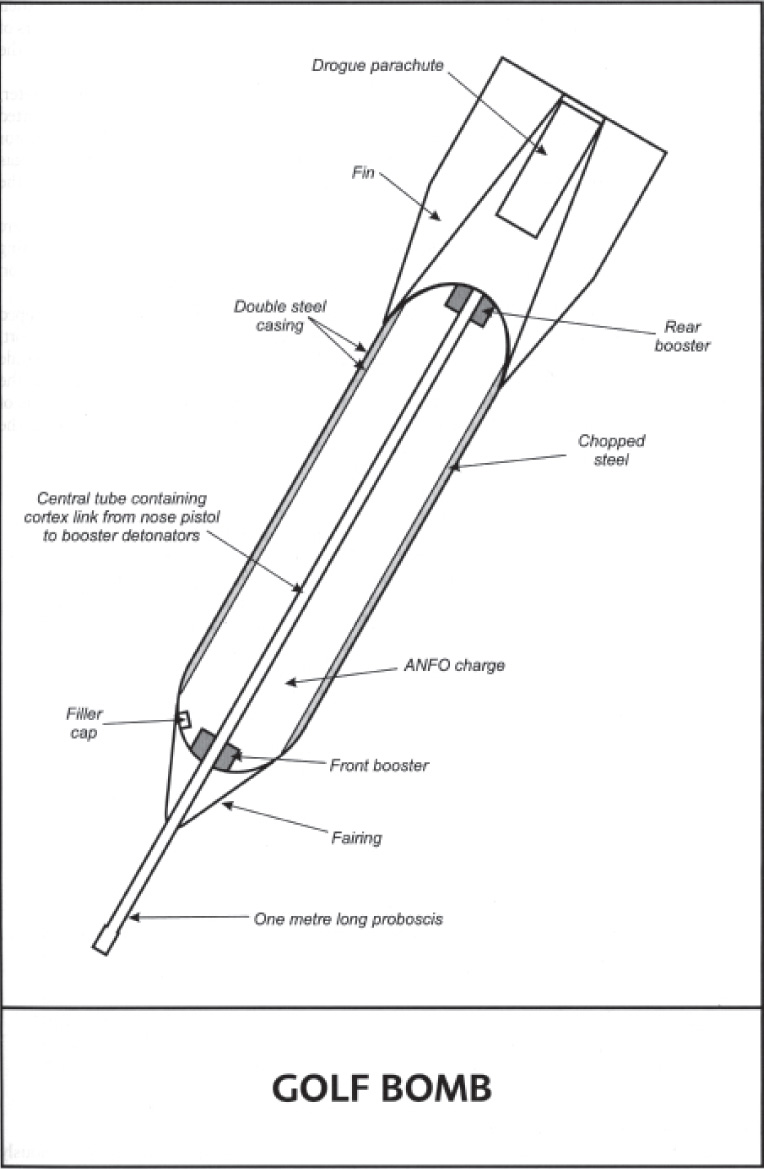

The second new bomb, the ‘Golf’ (being seventh in the series of projects) was ready for production by March 1977. Seeking a percussion bomb to clear bush-hiding insurgents, Petter-Bowyer had toyed with the concept of a fuel-air bomb using ethylene oxide. As the latter was unstable, expensive and difficult to procure, he settled on a 450kg double-skinned ANFO percussion bomb. In this case some 71,000 pieces of chopped 10mm steel bar filled the space between the skins. It sported a 984mm-long probe in the nose which contained a pentolite booster charge which meant it would explode the bomb’s 123kg of ANFO above ground. A second pentolite charge in the rear of the bomb casing detonated simultaneously, compressing the explosion to ensure maximum sideways effect. The compression of the explosion was such that the tail fin was often found at the impact point. The shock wave travelling at 2,745 metres per second was capable of stunning at 120 metres. The Golf bomb would be released by a Hunter at 4,500 feet above the ground in a 60° dive at 400 knots. As the safety height was 2,000 feet, the aircraft required a six-G pull-out to avoid shrapnel. The bomb would impact the ground at a 72° angle and clear 90 metres of bush, killing anything within that range with blast and beyond it with shrapnel. The Golf bomb’s safety distance for supporting troops was 1,000 metres if they were behind solid cover and 2,000 metres if they were in the open. The early version of the Golf had one bomb in a pair retarded by a vane to separate their points of impact for maximum effect. The vane was soon replaced by a more efficient locally made drogue parachute. The result was a bush-clearing pattern some 90 metres wide and 135 metres long.

The stunning success of this bomb led Petter-Bowyer and his team to provide the Lynx in 1978 with a similar capability to flatten the bush and to kill men in cover by designing the Juliet or Mini-Golf. Again it had a double skin filled with chopped steel bar. It had, however, no tail. Instead it had a large drogue parachute which arrested its fall and ensured it impacted the ground vertically. The nose cone held a steel ball or ‘seeker’, the outer casing of an Alpha bomb, which contained an electrical contact switch and was attached to a five-metre-long electrical cable. This connected the switch to the bomb’s batteries and to the detonator sited in the rear of the ANFO filling to achieve a downward and sideways explosion. The release of the parachute coincided with the dropping of the ball. The optimum height for the release was 300 feet above ground to allow time for the pendulum movement of the seeker to settle down and to strike the ground vertically beneath the bomb. The detonation occurred when the switch struck the ground, producing a fivemetre-high, shallow, cone-shaped blast of 30–40 metres’ radius. This would not only shred the bush but also kill anyone hiding in depressions, behind rocks and the like. Flight Lieutenant Spook Geraty, flying a Lynx, used the first bomb in anger on 18 June 1978. On 20 June, the renowned recce pilot, Flight Lieutenant Cocky Benecke, dropped four Mini-Golfs, killing seven insurgents. The Mini-Golf became a standard Fireforce support weapon. Too many failures to explode, however, led to the replacement of the cable detonator with the metre-long probe of the Golf bomb.

Diagrams by Genevieve Edwards

To enhance the capability of the newly acquired Lynx further, Petter-Bowyer’s project team also sought to improve the locally manufactured light frantan/napalm bomb, a metal cylinder with front and rear cones. The name ‘Napalm’ derives from the original 1943 ingredients aluminium naphthenate and aluminium palmate which were used to thicken petroleum into a gel. This has been superseded by Napalm B, a mixture of benzene, gasoline and polystyrene-thickener which burns at 850° Celsius and three times longer than the original gel. Some Western bombs were simply metal tanks, others metal cylinders with fins to pitch them downwards and away from their parent aircraft. None had stabilizing fins which made accurate delivery impossible but then napalm was intended to be an area weapon and usually dropped in clusters. Counter-insurgency demands accurate weapons to limit damage to unintended targets and thereby to public morale. The Rhodesians required a bomb with a predictable trajectory so that accurate aiming was possible, preferably with a forward fiery splash. The Rhodesian-made 17-gallon napalm bomb gave unsatisfactory results in terms of accuracy, spread and unburned fuel because the bursting charge ruptured the steel container in an unpredictable manner. The Lynx, being a light aircraft, also required the least drag possible when fitted with the bomb. What was required was an accurately delivered low-drag container that decimated on impact and sprayed the napalm droplets evenly. The Rhodesians moulded their new container out of woven glass net reinforced with asbestos fibres and bound with phenolic resin and, to ensure detonation, added two modified Alpha bomb fuses to ignite the flash compound. The resultant 16-gallon ‘Frantan’, or frangible tank, shattered on impact and spewed forward a cloud of flaming droplets. This gave the Lynx the ability to bomb accurately and predictably. These characteristics led to Hunters being armed on occasions with the new 16-gallon bomb in preference to the imported, and therefore expensive, 50-gallon steel napalm container.

A key requirement of air support in any counter-insurgency effort is an accurate and reliably visible target marker. The RRAF had experience of rockets, having acquired stocks of 60lb air-to-ground rockets, dating from the Second World War, which were fitted to rails under the wings of its jet aircraft. After 1965 it procured by devious means internationally the French-made Matra 68mm rockets and pod dispensers for its Hunters and the SNEB 37mm rockets and pods for its light aircraft, the Provost, the Trojan and the Lynx. The Rhodesian technical team was able to adjust the firing mechanism of the pods to allow the firing of single rockets or ripples of them.

The 37mm rocket, however, disappointed the Rhodesians because the head often buried itself on contact with the earth before detonating, throwing its fragments mostly harmlessly upwards. The problem of the target marker was solved in the early 1970s by inserting a mild steel tube containing 200 grams of white phosphorus between the high-explosive head of the 37mm rocket and its propellant chamber. The marker rocket was not only successful but improved the fragmentation of the head. Petter-Bowyer’s team then improved the explosive effect of the standard rocket tenfold by filling the extension tube with 100 grams of TNT, producing the ‘Long Tom’ rocket. Hundreds of the smoke and explosive extensions were machined, filled and assembled by the air force armourers at Thornhill. The heavier extended ‘Long Tom’ rocket was slower in flight but just as stable and accurate.47

A little-used, cheap weapon invented by Petter-Bowyer to arm the Hunter was nothing more than a six-inch steel nail stuck into the three-finned plastic flight of a playing dart. A local nail manufacturer supplied Petter-Bowyer with the headless nails. To achieve a wide dispersal on release, 4,500 darts were tucked together alternatively forward and backward and packed into a four-panelled, streamlined fibreglass container or dispenser. A pair of dispensers would be fitted to the hard points under a Hunter’s wing. Diving at 450 knots, the pilot would line up on his target with his gunsight and release the dispensers. After half a second of flight, explosive charges in the nose cones of the dispensers would split apart their panels, releasing a cloud of darts. The flying nails, pushed wider by their neighbours’ slipstream, would fan out to cover a wide area. The contents of a pair of dispensers would riddle an area 70 metres wide by 900 metres long. On 30 October 1977 this happened in a contact in the Sengwe Tribal Trust Land in southeastern Rhodesia with eleven insurgents being killed in the area of the flechette strike.48 On 27 May 1979 flechettes killed 26 top ZANLA commanders after an observation team overlooking the Burma Valley on Rhodesia’s eastern border had spotted their meeting. The leader of the group was struck by 26 flechettes.49 This silent killer was greatly feared by ZANLA. Its use, however, was limited by it being named ‘flechette’ before it was realized that the ‘flechette’ rifle round was an internationally banned weapon. The result was that it was decreed that it should only be used internally or in remote external areas.50

46 Petter-Bowyer, pp. 272–276; Anon, ‘The Armament Story’, The Zimbabwe Medical Society Journal, Issue No. 61, March 2008.

47 Cowderoy & Nesbit, pp. 119–124; Interview, Petter-Bowyer, 24 March 1992, information supplied by Alf Wild.

48 Petter-Bowyer, p. 303.

49 Petter-Bowyer, p. 353.

50 Anon. ‘The Armament Story’, The Zimbabwe Medal Society Journal, No. 61, March 2008, p. 29; Cowderoy & Nesbit, pp. 119–124; Interview, Petter-Bowyer, 24 March 1992.