“IT’S WHEN YOU FOLLOW YOUR FAULT LINES, CHOOSING THE APPEARANCES OF THINGS OVER THE THINGS THEMSELVES, THAT YOU TAKE THE WRONG PATH AND MAKE A FOOL OF YOURSELF.”

I don’t know where Mam Jeanne finds phrases like that. If what she tells us is to be believed, all she knew in her childhood was the gray cover of the syllabaire1 and a book of mental arithmetic that stopped at the rule of three. Perhaps adages do have some truth to them, age sometimes bringing with it reason. And old women are the ones who begin speaking like a book in grave times, even though they’ve never read anything.

When we’re sitting on the curb in front of Mam Jeanne’s house, it’s one of our favorite subjects, me and the little professor: ages and paths. Why are you coming here and not going there? Which part of you controls the path that you’re following? Do all steps lead somewhere? Popol, my brother, says that I took my first step at one year old. That means I’ve been walking for twenty-three years. I know exactly how many steps are between the curb in front of Mam Jeanne’s house and the main entrance to the great cemetery, between the great cemetery and the linguistics building, between the linguistics building and the branch of the commercial bank where the armed foreign service members in uniform sometimes go, between the branch of the commercial bank and my sidewalk curb. I also know that, ever since childhood, all of my steps bring me to the curb in front of Mam Jeanne’s house. My place of meditation, where, as the sentinel of lost footsteps, I spend my time pondering the logic of pathways. Sentinel of lost footsteps. The little professor is the one who calls me that. And yet he’s just like me, only thirty years older. Or I’m like him, thirty years younger. Sentinels of lost footsteps. We spend a lot of time talking about paths, without being able to change anything about them. And in the evenings, we ask ourselves questions that remain unanswered. What path of poverty and necessity could have led a boy born in a Sri Lankan village or a shantytown in Montevideo to find himself here, on a Caribbean island, shooting at students, robbing laborers, obeying the orders of a commander who doesn’t even necessarily speak the same language as him? Of what use is the part of his salary that he sends home to a mother or a wife? Did he rape someone for the first time in his home village, maybe a childhood friend or a cousin? Or is that a habit that comes with estrangement, with the discomfort of barracks in an unknown country? Did he learn from his peers? When you’re dying of boredom and in possession of weapons, violence can serve as a collective pastime. And for that umpteenth teenager who was found dead next to the military base where the soldiers born in Sri Lanka or Montevideo or anywhere else in the world were kept, what need for tenderness or money or maybe for travel pushed him into the arms of his rapists? Between Julio, the most solitary boy of Burial Street, who hides the fact that he doesn’t like girls from others and from himself—because even on our street, overpopulated by the living and the dead, there’s a place for secrets—and the boys who sleep in the beds of service members in need of exercise and high-ranking officials of the Occupation, will any of them ever be the masters of their desires and bodies? And the pretty spokeswoman from Toronto or Clermont-Ferrand who will placate the media, talking about the investigation currently underway into the teenager’s death and of the first findings which, of course, point to a suicide—at what age did she learn to lie? Does she also lie about her loves and desires? What is being? Between a journey that ends in catastrophe, or a collapse right where one already is, what is the heaviest kind of defeat? What future awaits a girl who grew up on Burial Street, with dead people rotting in the tombs of the great cemetery for neighbors? I am thinking of Sophonie and Joëlle, the two women I love. I believe that I’ve always loved them, without ever feeling the need to choose between them, or even get too close to them. What kind of future will they forge for themselves? I am thinking, too, of the little brunette who works for the United Nations civilian mission, the one I watch every Wednesday, so sad and so proud at the wheel of her service vehicle. What path of arrogance and depression did she follow to get from her Parisian suburb to her current position, from her childhood to the Wednesday nights drinking beer at Kannjawou, the restaurant-bar? And me—where am I going? For the moment, I’m living through this journal, which I keep in order to stay focused on my occupied city and on my neighborhood, which is inhabited by as many dead people as living ones, as well as the comings and goings of the thousands of strangers I come across, and those of the ones I’ve never really come across. You can make out only their outlines behind the tinted windows of their luxury cars and official vehicles. Today, I’m idling on my sidewalk curb, playing at being a philosopher. But tomorrow, who will I be? And how will I, like everyone else, live truth and falsehood, and strength and cowardice, at the same time? Which self do you end up becoming, and at the end of which path?

THE LITTLE PROFESSOR ARRIVED FROM ANOTHER ERA AND ANOTHER NEIGHBORHOOD WITH THE SAME QUESTIONS. And in the evenings, when he leaves me on my sidewalk curb and returns to the solitude of the library, I know that he is bringing our questions with him. I stay and listen to the sounds of the cemetery. If I ever write a novel, as Mam Jeanne, Sophonie, and the little professor have suggested, the cemetery will be its main character. All major characters have two lives, two faces. The cemetery has two lives. One of them, the official one, is during the day. With funeral processions. Grief laid bare to the commotion of the crowds. The speeches of officials. Instructions for standards, order, positions. Fanfares and grand scenes of despair, like a big street theater play where everyone knows exactly what his or her role is: the moment when this lady should lose her hat, or that one should lift her arms to the sky. The schedules that dead people and their companions must follow. During the daytime, the cemetery is careful to preserve its image, just like a person. But in the evenings when the shows are over, it has another life. A more secret one, but more a truthful one, too. A crazy one. The pickaxes of the grave-robbers. Their pranks. Their laughs, sometimes, a little noise so that they can breathe, for silence makes death feel all too present. The shadows who murmur prayers to gods who can’t be called upon in front of everybody. The homeless people or thugs who pile into tombs that they refer to as their “apartments”. The black candles. Mam Jeanne tells us that once upon a time, after the sun had set, ministers and generals and artists and businessmen would often come to the paths of the great cemetery. Talent pillagers, who would spoil the grave-robbers’ job prospects by seizing one or another corpse in particular in order to take away a part of its body—a hand, if he had written well, or its better foot, if he had played soccer—and wield it like a talisman. It is a weakness of the living to want to usurp the qualities of the dead. Accompanied by sidekicks—magicians and professional killers—they came to assure themselves that this enemy or that rival would never be seen again, or to try to extort the secret of their success from their dead body. Apparently, even foreign dignitaries would come to steal ideas from dead geniuses. The craziest beliefs and the most perverse vices are universal. But these days, talent pillagers have become rare. Our dead people no longer hold any appeal. The rich, the gifted, and the other high-quality people have left to die somewhere else. Wealth and poverty, and success and failure, have always been waging warfare here. The richer I am, the farther away I go. Catch me if you can. The great cemetery isn’t the resting place for great men anymore. Its new inhabitants and their visitors are unknown people with ordinary lives. The only ones buried there are the lesser people, dead of ordinary sicknesses that a doctor would have been able to cure. Little, unimportant corpses, who invented nothing and don’t deserve a place in the shackles of memory.

I’VE HAD THIS HABIT OF KEEPING A JOURNAL SINCE CHILDHOOD. For my sixth birthday, Sophonie gave me a notebook. Sophonie has always had the gift of being one step ahead of others, understanding their needs and expectations even before they do. I remember that there was a lion on the cover and that my classmates laughed at it. Writing is not in fashion on Burial Street. It’s a rare type of madness, and spending time far away from the commotion of parties and brawls makes you a kind of foreigner. During my childhood I would go seek refuge at Mam Jeanne’s house so that I could write. She let me scribble whatever I wanted in silence. But then the moment would come when she couldn’t stop herself from talking about the first Occupation. She didn’t call it “the first” because she wasn’t expecting a second one. I’ll never forget the day when the foreign troops arrived. She shut herself up in her room with her cat, Loyal, and didn’t utter a single word the whole day. I think it was the only day I’ve ever seen her cry. I was thirteen years old. I had never seen so many weapons and tanks outside of movies. Popol, Wodné, and Sophonie tried to mobilize the young people, telling them: we must do something. Joëlle and I followed them without knowing what to say. We didn’t speak the right language. Two or three years can make a big difference when it comes to mobilizing. “Mobilization” was the rallying cry, but we didn’t “mobilize” as such. The adults—the shoemaker, the undertakers, the akasan* vendor, the old bookbinder who already had very few old books to bind—demanded that we leave them the hell alone, shouting to us that there wasn’t anything left to preserve. Not dreams. Not dignity. The kids threatened to smash our faces in. Only Julio had accepted our invitation. He prefers boys, but not shaved heads. There weren’t many voices of protest. It was as though people had gone to bed. As though it was the whole world that had taken possession of our streets. The occupiers’ ruse was the abundance of flags, colors, uniforms. The friendly smiles of the generals and the spokespeople. Their rhetoric of friendship and multilingualism. How can you revolt against an enemy that’s constantly changing its tone and its face? Of all the kinds of unhappiness, without a doubt, the worst is powerlessness. Everything played out above our heads. Both literally and figuratively. Planes and helicopters. And the heads of state who had said yes, you can come to our country. And the private English and Spanish teachers who were suddenly now making a fortune. Popol, Sophonie, and Wodné, who led Joëlle and me, weren’t taking the failure of their first initiative well. When you’re fifteen years old and love your country, you might then wonder, what kind of temple is it when its caretakers turn into doormats, brown-nosers? Ten years later, that feeling of abandonment—and above all, that anger—hasn’t ever left us. Anger about everything, angry at everyone and at ourselves. This anger will kill us, or will cause us to kill, maybe, taking aim at the wrong target. I think, too, that powerlessness has divided us a little bit. It was at that time that Popol and Wodné had their first conflicts. Before, nothing had ever separated them. Defeat brings with it division, and the end of any lost battle brings reproach for any fellow fighter who didn’t fight well enough. Out of all the adults, Mam Jeanne was the only one to really welcome us. On the night of the landing, she had come out of her room, motioned to us to come inside, offered us tea, and said, “My little ones, this is a land without anyone in charge. Look at these people marching in the street. No one is watching over them; no one’s fighting for them. And it’s always been like that. So all these vultures come to prey on them. You will suffer. We will all suffer. And suffering needs air, it needs space. You can spit on it or you can suffocate. So, when it comes time to spit, don’t go after the wrong target.”

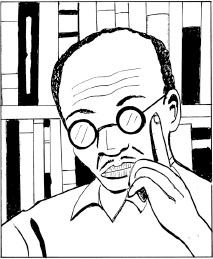

WHEN YOU’RE ANGRY OR ALONE IN AN IMPASSE, YOU BELIEVE THAT THINGS HAVE ALWAYS BEEN THE SAME. Exhausted from constantly searching for the right words or a good attitude, Mam Jeanne sometimes wails that it’s always been the same, ever since her childhood. And yet she’s the one who told me that even underneath what seems like emptiness, there is movement. She’s the one who told me about the resistance efforts against the first Occupation. She’s the one who told me not to spit on the wrong targets. You can’t ask someone—even a force like Mam Jeanne—to be one hundred percent clear-sighted twenty-four hours of the day. We’re all allowed to get a little worn down. When Popol, Wodné, and Sophonie began to take an interest in politics, they did some research. Joëlle and I followed them everywhere, in their footsteps and in their thoughts. That was how we learned the history of the lost battles, the sacrificed lives, the efforts of those who had dreamed of a better life for everyone. Always. Before, after, and during the periods of dictatorship. Before, during, and after the first Occupation. There had always been brave souls to say no. The little professor had fought, too, in his own way. In the corner of his library, he has an old mimeograph machine, like a relic from another era, and I assume that it was used to print illicit pamphlets and newspapers. I also once met an old man at his house who doesn’t talk very much. But I know who he is: Monsieur Laventure. The dictatorship had stolen his wife from him. He spent three years in prison. No one had seen him since his incarceration, and everyone believed him to be dead. But one day, he came back to life. Skinny. A matchstick of a man. He had been kept in isolation. His “widow” had married his best friend and his oldest comrade-in-arms. They are still together, and he has stayed alone, all while taking up the fight again by their side. I’m afraid to approach him, and have never dared ask the little professor to make introductions. It’s not easy to see a legend, a hero who has led a life of battle and sacrifice, up close. That’s how he’s spoken of in the progressive circles at the university. I don’t know what there is between him and the little professor. The little professor has never described himself as a “militant”. A bit of mystery resides in even the most open of people. And for them, secrecy was how they survived. They’ve held on to their reflexes from times past. During the dictatorship, if you spoke, you died. The little professor tells us with a smile how, in his youth, when there were more than three of them and one of them was keeping quiet—even if they were talking about soccer or their studies or love affairs—the others would ask him to open his mouth and say something, anything. A joke about the weather, a psalm, a La Fontaine fable. Because if the secret police arrested them after their conversation, the torturers would ask them to report exactly what each of them had said. “You have to say something, so that the others don’t have to invent something, or be beaten, for your silence.” Today, you can speak. Everyone speaks. A teacher who’s more preoccupied with his career than with the lives of others can play at being a revolutionary during class. On every street corner is a man or a woman who harangues the people hurrying by. The Occupation’s civilian staff has multiplied the number of conferences and seminars that obedient job seekers can attend. There’s no shortage of declarations of intention. You even hear, ten years too late, voices denouncing the occupiers. Everyone speaks. And words allow you to score a few points in the scramble to look good. That’s called democracy. If you lie, everyone listens to you. If you tell the truth, no one will listen to you anymore. They’ll respond to you with the gentle voice of a pretty, tanned spokesperson, saying that it’s nice that you’re expressing yourself. But the guns remain. And the tanks. And the unhappiness. And it’s still every man for himself. These days, it’s crazy what people talk about, but does talking still serve any purpose? Sometimes, the little professor and I fall into silence on my sidewalk curb. I love that man, but deep down, I don’t know him well and I still don’t understand him. I could ask him, too, about the unplanned paths that people wind up following. It’s true that he comes from the other side of town, and here, every neighborhood is a little world with its own laws and codes.

THE LITTLE PROFESSOR WAS BORN ELSEWHERE. Up high, is what Wodné would say—Wodné, who divides the whole land into two regions: down below, up high. It’s a very simple kind of geography, an implacable one, which he applies to humans, too. Those from down below. Those from up high. He claims that it’s a mistake to want to cross the border. That once you’ve changed sides, it’s impossible to return. Every human should live in their own place, shouldn’t force their destinies by entering a world that belongs to other people. Sophonie sometimes comes back from the bar where she works with stories about the customers. Wodné never listens to them. “The customers’ problems aren’t the same as those of the servers. The Whites. Or the almost-Whites. It’s a bar for the occupiers and their assistants. For those who are connected.” I can’t say that he’s wrong to point out these differences. And it’s true that the money that the clients in the bar drink down is procured by our poverty. The bar is called Kannjawou. A beautiful name that means a big party. But Burial Street isn’t invited. You have to pay to go to rich people’s parties. When poor people come close, all the rich have to do is raise the prices to discourage them. Sophonie is the only one in the neighborhood who goes to Kannjawou. And Popol and me, who accompany her on Wednesdays because her shift ends very late. But she doesn’t enter through the main door. Just like the servants at the little professor’s house in the old days, who didn’t have the right to use the main entrance. From time to time, the little professor consents to talk to me about his childhood. His father was a notary public at a time when, although they weren’t exactly rich, the notaries were Latinists and scholars who wove quotations from Bourdaloue or Montesquieu into their conversations. Montesquieu at the dinner table every evening. Quotations followed by exegesis. And his mother had taught him table manners: it’s not the mouth that goes to the fork, it’s the fork that raises to the mouth. He laughs about it and admits to having disappointed his parents a little by choosing to be a professor, a difficult career path. He believes that the blame lies with novels. He read many of them during his childhood. Too many, perhaps. They allowed him to imagine something else, a world, a light, beyond the rules of deportment, procedural flaws, Jesuitism. He still reads them and lends me as many as I want. I go to his house to borrow them, or he brings them to me. Novels. It’s one of the things that connect us. Him, an almost-rich man who in his childhood had the luxury of choosing which of his two parents he liked better, who lives in a neighborhood where flowers still grow, in a two-story house with a guestroom, who possess a car he rarely uses, and a library in which there are more books than there are tombs in the first section of the great cemetery that encloses our street. And me, a little guy from Burial Street who had only his brother Popol for a parent, who has never eaten to satisfaction, who has never been taught the art of holding a fork. In his childhood, he read to appease boredom. For me, it was often to appease hunger. The truth is, whether you’re nobody’s son or a notary’s son, you need a lot of sentences and characters in order to build up a sort of land in your head, filled with hiding places and refuges. With all due respect to Wodné, who hates when people move, our heads are full of travel. The little professor and I—he in his bedroom belonging to the son of a notary, where his mother would come in to tuck him in and turn out the light, and I on my sidewalk curb or in the little house without a shower or a bathroom that I share with Popol—we have been, on occasion, swordsmen and astronauts, rebellious and passive, inventors, knights in shining armor, prison escapees, poets and mercenaries. It doesn’t matter if our reasons are different; the little professor and I have walked far in the world of books, where we’ve met many people whose destinies have haunted us, just like those of the living.

THOSE LEAFING THROUGH THE PAGES OF THIS JOURNAL MIGHT PERHAPS FIND NOTHING OF INTEREST.

Nothing happens. Nothing, in any case, that’s worth the trouble of telling. An occupied country is a lifeless land. I could write down that the old bookbinder only gets by thanks to the work that the little professor and a few scholars bring him. That he doesn’t see very well anymore and that he no longer can control his movements well, so that when he hands the books over, his few clients notice that the title doesn’t match the book. I could write down that the cobbler couldn’t find any customers and had to close up shop. That the Halefort gang works at a frenetic pace, robbing corpses with the speed of a machine. That matches are still played at the stadium, and powerful but clumsy players sometimes take shots that pass over the bleachers and take off towards the cemetery. That our two major neighbors, the stadium and the prison, have opposite destinies: the bleachers at the stadium don’t receive many people anymore, while the prison never empties out. To the contrary, in fact: its population never stops growing. All that is true. And more things, too. But an occupied country is a land without a sky or horizon, where it would be wrong to believe that as long as there’s life, there’s hope. Everything that I could write down in this journal would only be an expression of despair, or of a fight for survival. At dawn on Burial Street, the windows look out onto sad faces. Women step out into the street to sweep in front of their houses, moving mechanically. They exchange greetings that are just as mechanical, and sometimes they sing laments sadder than funeral chants. The Occupation is dead calm. The city has become a vast prison, in which each prisoner seeks his own sliver of life, mistrusting others. Not everyone is given the power to make a detour and think about something other than their own survival. Sophonie and the little professor are my heroes because they are capable of such detours. Sophonie is a whole family unto herself, and always has been. The bread for Joëlle and their father, Anselme, that’s all her. The idea for the Center for kids, that was all her. Managing conflicts among our group of students and youth, that’s all her. The self-confidence that Popol has acquired, and the useful and modest plan of action he’s developing, that’s all her. I’m angry with myself for preferring Joëlle to her, at least with my eyes and my body. You can love two people at the same time, but maybe not in the same way. Ever since childhood, I have loved Sophonie with too much respect, and Joëlle with too much indulgence. In the shadows. In the solitude of my notebooks. And when I have wanted to love them for real, hoping to hold their hands or try to kiss them, Popol and Wodné have held me back. In the group, I am the little one, the youngest. And the scribe. Mam Jeanne encourages me. Write about your rage, the passing time, the little things, the country, the lives of the dead and the living that inhabit Burial Street. Write, little one. I write. I take note. But we won’t get rid of the soldiers and make the water run again with words. Yesterday they attacked protestors again with rubber bullets and tear gas. Perhaps one day, it’s they who will get rid of us.

THE LITTLE PROFESSOR HAD TO MAKE A LARGE DETOUR IN ORDER TO COME TO US.

One day, in the courtyard of the humanities college, he heard Popol talking about the cultural center that we had created for the neighborhood youth. When you’re faced with political failure, you can sometimes take refuge in songs and poems. The Center gives us the feeling of being alive and of being able to take some kind of action. Popol was talking to a professor who was a sort of mentor to several students. A loudmouth who sometimes supported our protests without actually marching with us, who’s never given anything to anyone other than undeserved excellent grades to his students. He was born on a street like our own. There are a lot like him who teach at the college. Who play at being progressive without particularly wanting to relive their pasts. They have no pasts, for that matter. The loudmouth was born at age thirty during his first trip abroad. His scholarship gave birth to him. While abroad, he learned that all our misfortunes—poverty, the Occupation—come from a chronic deficit of “scientific thought”. “You’ve created a cultural center for the neighborhood youth? Is your approach based on scientific thought, or is it another one of those folkloric initiatives that’s useless for modernity and development?” All of his sentences begin with “scientific thought.” He never visited our Center. It was too small for him. He was busy preparing poses and expressions in front of his mirror and inventing an accent that existed for only his mouth. The loudmouth specializing in “scientific thought” never came to Burial Street. But one Saturday we saw the little professor arrive with boxes of books. Stunned but polite, Popol took him on a tour of the premises. Things here are all so small, decayed, or wobbly that it’s almost ridiculous to give them names: studio, bedroom, meeting room. Here, other than the great cemetery, which looks like what it’s called, the names we give to things never correspond to their realities. Our premises! It’s a passageway between two houses. Not even a corridor. A clearing between walls, sheathed with four little bits of sheet metal. Mismatched chairs. Holes in the walls. A few books on a lopsided shelf. A non-place transformed into a discussion space, despite the heat when it’s sunny and the leaks when it rains. As decoration, there’s a faded banner that says “Down with the Occupation,” some children’s drawings, and a badly aged photo in which you can barely make out the features of Charlemagne Péralte.* Only his mustache is still visible.

“Is it true that his grave was dug deeper in the earth than the ones in the great cemetery?”

“Yes. We have to talk about these things: no grave has ever been dug with so much anger. Deep like an abyss. As though it was to drown his body in the bowels of the earth. But you can’t bury legends with a pickaxe.”

“So we’re hanging up his photo. And no one is allowed to mess with his mustache with ink or pencil. Anyway, we don’t have ink or pencils.”

It’s Hans and Vladimir who are speaking like that. Two of the cleverest kids, and also two of the most skillful when it comes to throwing stones. They’re famous for having broken the windows of a military truck. Mam Jeanne threw a party in their honor, with cake and liquor. They welcomed the little professor on behalf of the others, sealing the deal with a handshake. Childhood also has its leaders. And in order to choose them—unlike fake wise men who hesitate and dither—they’re smart enough to elect their friends and to get to the heart of things quickly.

THE CHILDREN CHOSE THE LITTLE PROFESSOR RIGHT AFTER HIS FIRST VISIT.

The next Saturday, he came back. In his shirtsleeves, with a larger reproduction of the Péralte photo, pencils, and colored paper. He helped Popol repair the shelf and install a few more. Then he read to the children.

“Hey, little professor, are you coming back?”

He told them that he would come back. Ever since, Burial Street has sort of become his street, too, and everyone calls him the little professor. He comes every afternoon. In the evenings, he and I ponder ages and paths. Wodné, who presides over the association and takes his title very seriously, is trying to find out the little professor’s hidden motives and advises me not to trust him. Why would a professor—the son of a notary, the heir to such a beautiful house—want to extend friendship to guys from Burial Street? I don’t know why. Or there is a major reason why. Without a doubt, he comes to see Joëlle. Sometimes they wind up talking, and she can’t see the expression in his eyes when he looks at her. Everyone sees how he looks at her. The children. Mam Jeanne. Even the old bookbinder, who doesn’t see much of anything anymore. Wodné sees it, too, and he can’t stand the tenderness and dazzlement in the little professor’s eyes. “Sensible hatred is a formidable weapon,” a great French philosopher once wrote. Wodné has hatred. It’s grown stronger over time. What does the little professor want? No doubt he has strayed from his path, like many others. Or his heart is leading him blindly. Allowing his footsteps to take him where they may. Without thinking any further than the children’s happiness and our evening conversations. Without planning anything. Like Sophonie, who still hasn’t learned to protect herself. She works. Takes correspondence courses, volunteers for organizations that protect women’s rights, takes care of Anselme. Some people are just there. As they are. In real life. And there are others whose very presence is a lie. An illusion. Effective when it fools the whole world. Ridiculous when it fools only the illusionist. Like that loudmouth who was born in a rural area and rolls his Rs in front of the mirror, who sings the praises of the occupiers’ scientific minds and plays at being brave when he’s got nothing to fear. There are also those who put off their existence until tomorrow. When the circumstances are right. At the university, there are many professors and students who repeat that phrase: when the circumstances are right. Are you going to the protest? When the circumstances are right. Will you help us start an organization with some people from the neighborhood? When the circumstances are right. What should we do to send the occupiers away? Wait until the circumstances are right. I don’t go to the university anymore. I’m pretending to work on a thesis about the history of the great cemetery. But I see too well how it happens. I’ve already written many papers. That’s how I earn a living. For rich people’s kids, who prepare for their futures by paying me to write their assignments for them and then put their names on them. It can be useful to know how to put sentences together. I don’t make out too badly. For the poor kids, those from Burial Street or neighborhoods like our own, I do it for almost nothing. But I’m not thinking about the future. No need to have a diploma to see how the circumstances for unhappiness were right a long time ago, and are still right. No need to have a diploma to know that the titles are worth more than the knowledge, and there’s a war on among those of us from Burial Street and similar neighborhoods to be the first to obtain the title of master or doctor and to flee without looking back, without ever looking back to watch the others running behind us. I don’t have any ambition. Living? To find a little bit of happiness from day to day. The little bit you’re able to find. To see the children laugh. To contemplate Joëlle in all her beauty. To walk at night with Popol and Sophonie. To drink tea at Mam Jeanne’s. To chat in the evenings with the little professor. Deep down, I don’t need very much. To write things down in my notebooks. Could it be possible that at my age, the time of wanting has already passed?

MAM JEANNE MAINTAINS THAT YOU WILL ALWAYS GO WRONG AT SOME POINT IF YOU MAKE TOO MANY PLANS. It’s good to follow your instincts, without claiming that your actions will fit logically into a vision of the future. Mam Jeanne doesn’t say anything that she’s not able to illustrate with examples. In this case, she’ll point out what happened to the sad dead people who were victims of bad speculation. When the cemetery was attracting as many rich people as a tourist site, wealthy and considerate parents would leave tombs in the great cemetery for their young or still-unborn children to inherit. A property title, sometimes given to a lawyer for safekeeping or put away in the trunk of family valuables, bestowing the right to a plot vast and deep enough to accommodate several generations in the best corner of the cemetery, at the end of a pathway lined with flowers. The calculation seemed accurate. The number of living people was increasing rapidly, and since all were someday going to die, you could assume that the total chaos that ruled over the city would also one day take over the cemetery. People walking all over it. Makeshift beds that they’d trade off occupying, sleeping only half the night. A perpetual racket that didn’t bode well for the dead’s repose. Rich people don’t like crowds. To shelter themselves from the barbarous invasions, they had to put up protections around their territory. Fences, concrete, lawns. Providing for their descendants. But by the time their heirs were born, lived, and died, they discovered the flowers that had once lined the pathways had dried up. The royal blue had faded, and you could see the sad color of the stones underneath the paint. A thousand rainy seasons had drowned the gravel and the lawn in a dirty sea. Of the little palace that had been built to serve as their last dwelling, only a dilapidated ruin remained, isolated in a swamp. The rich people that are buried today in the great cemetery at the end of Burial Street are considered to have come down in the world. If they had been able to choose without betraying their families, they would have rejected their own burial plans and followed the example of the nouveaux riches who fled the old city, even in death, and paid for graves in the new cemetery. The one further north. The beautiful cemetery that sits atop agricultural land bought from peasants. Too far away for pedestrians, and lit up at night like a Christmas tree.

MAM JEANNE IS RIGHT. Sometimes things change so fast that it would be wrong to imagine you could have thought about them ahead of time. The cemetery at which our street ends used to be called the outer cemetery. Today no one calls it that anymore. Houses have sprung up on the hilltops, replacing trees. Humans, unlike trees, don’t have their feet incrusted in the earth. They only know how to walk on top of it. And so the earth takes its revenge. Each human step brings up dust. On windy days, big specks of it blow down from the hills, leaving a white powder on the ladies’ black hats and the gentlemen’s dark jackets. During our childhood, our gang of five used to like to climb up to the tops of the hills to look at the dead people that were furthest away. And the stadium. And the two cathedrals, both the old one and the new one. And the Tax Directorate building. We had the city at our feet. Two cities: the one that we knew, and the one we could only imagine. We are from a city in which multiple forbidden towns cross paths. In our ramblings, we would sometimes come across a neighborhood with gates as high as prison walls and dogs that barked loudly and stayed at their houses. We knew then that we had gone beyond the boundaries of our own city. You don’t enter the other half of the city with five people at a time. It’s a solitary path, and you can’t follow it without betraying your own intentions. We didn’t know this. We were the gang of five. I had borrowed this phrase from something I’d read and thought that it described us well. We were the right age. Even if we didn’t have a scholarly father lost in his work. Even without a father at all, except Joëlle and Sophonie’s father Anselme, who had told fortunes to earn a living before falling ill and who swore that one day he would take back the land that had been stolen from him in Arcahaie. Anselme was not aging well. Gout and delirium. The girls had to mother their own father. But childhood is rebellious, and you can get revenge on the real world by dreaming up your futures. We dreamed up the future. Joëlle spoke of the handsome gentlemen who would take her far away. Wodné and Popol sketched out landscapes in their heads. Wodné wanted skyscrapers and highways. Popol thought that Wodné’s landscapes were lacking in soft colors and imagination. Sophonie said that you should never wait around for dreams to come true, nor leave your responsibilities to someone else. If she wanted to leave, she wouldn’t need anyone to serve as her guide. She would bring back flowers from her long walks, which she kept alive in pots that she would place on the windowsill of Anselme’s bedroom. The four of them talked all the time about changing the world. The courses of study they would have to follow. “It takes knowledge to change things.” The actions they would need to take. They mentioned the names of the heroes who would serve as their examples. As for me, I drank up their words. Other than that, I was lost in my novels and I came out of them only to ask myself a question to which I still don’t know the answer: which of the two sisters was my favorite? Joëlle was the imp who wasn’t afraid of anything. She had learned everything very fast. Faster than the others. By the second grade, she’d already caught up to them and was the best in her class. I loved hearing her discuss things on the same level as the others. Especially with Wodné, who always cheated when he was losing and then looked very sad, as though he were going to die, when someone beat him. Sophonie brought me books that she borrowed from the middle school library and from her wealthier friends. She was already almost a young woman, with curves and breasts. Joëlle was still only an idea. A skinny little thing who walked fast, forcing us to keep up with her. But I was a reader of novels, and like many characters in those novels, I had a hard time choosing between what was and what would be. Between the potential and the possible. I used to go ask Mam Jeanne if I could love two people at the same time. Also, why the children of Burial Street, unlike the children I met in my novels, never had more than one parent. Or had no parents at all. Sophonie and Joëlle had only Anselme. Immacula, their mother, had died when Sophonie was four and Joëlle was still a baby. Wodné, who lived with his aunt, had a mother who lived in the countryside. Popol and I didn’t have parents at all, and we hadn’t for a long time. It was the same for the kids who came to the Cultural Center. One out of two parents in the best of cases. It was one of Sophonie’s ideas, the Center. For the kids. They didn’t have parents, but we could at least give them a place to make friends. And to dream up the future, like we used to. Children have things to tell each other, too. Sophonie went to see Mam Jeanne to tell her about her idea. Mam Jeanne thought it was a good one. “Young people did things like that during the first Occupation. Some good people came from it. Not all of them. For some people, however much you expose them to the best, they’ll always choose the worst. But let’s create this Center for kids.” She organized a fundraiser and then gave us the money that she had collected for us to buy the first books. Wodné wanted instructional texts that would serve as introductions to civic education and social consciousness. Sophonie preferred equal amounts of everything. Why couldn’t poor children descend twenty thousand leagues under the sea, travel in a hot air balloon, and fight with swords to avenge their friends? If you don’t have dreams, why would you want to fight for them in the real world? Mam Jeanne settled the argument in favor of an even split between dreams and reality. She also went to see the owners of the houses on either side of the corridor, who engaged every day in a war of abuse and trash. Put a stop to your arguments over a strip of land that’s of no use to you. Handshake. Done deal. She passed on the message that nobody would throw their trash into the corridor anymore. Frantic lovers would have to content themselves with a tomb or the little passage behind the cobbler’s workshop. Or the workshop itself, since old Jasmin never opened it anymore, except to air it out. It had been a long time since anyone had brought him shoes to repair. Mam Jeanne had convinced everyone by threatening to pour cat piss on their heads. It’s a practice that goes back to the first Occupation. Her first victim had been a Marine who had ventured onto our street one night. “It’s already too much that they’re screwing over our living. But they’d better leave our dead the hell alone.” She has a technique for getting cat piss into a container. She’s had a long series of cats, whose names she inscribes on a seventy-five-year-old almanac that she’s never dreamed of taking down from the wall. The latest one is Loyal, who will die soon. The collaborators, those show-offs—many of them have earned their dose of Loyal’s piss. No one wanted to ignite the wrath of Mam Jeanne, and everyone brought what they could for the Center. The cobbler, the old bookbinder, the fried-food vendors, the unemployed… Even Halefort, the leader of the grave robbers, showed up with his gang. They brought sheets of metal and even did the handiwork themselves voluntarily. After all, during the day, grave robbers are ordinary citizens, and there’s nothing to stop them from contributing to the life of the community.

TODAY THE GANG OF FIVE NO LONGER EXISTS. Sometimes we go get a beer together, but the atmosphere is always tense, and what’s the point of repeating an unpleasant experience over and over? Perhaps there’s nothing worse than reaching adulthood in an occupied city. Everything you do comes back to that reality. Friendship requires a foundation of dignity, something like a common purpose. We’ve now lost the future, our common interest, always hypothetical. We live in a present of which we aren’t the masters. Every uniform, every administrative procedure we have to undertake, every news report reminds us that we are subordinates. Julio still doesn’t like shaved heads, but he met someone—I don’t know how—who works for the civil mission. He fell in love with his long hair. The officer with the long hair sometimes comes looking for him in the evenings. The scrawny little boy we used to make fun of at school has become a young man with fine features and gentle manners. It works pretty well for Julio to resemble a young girl. The little professor and I watch him climb up into the diplomatic service’s armored vehicle. From her balcony, Mam Jeanne pretends not to see anything. I think she hasn’t managed to decide on which attitude to adopt regarding Julio’s love affairs. These things are never straightforward. Julio has changed. He smiles. And a smile is a good thing for a boy who used to live in the silence of his little room and the solitude of his desires, never laughing, never talking, who had no friends, who feared assault from those whom he loved. We all change. And you can’t always tell if it’s a change for the better or for the worse. Joëlle became the most beautiful of all the girls. She could choose whoever she wanted to be her lover. Strangers stop their cars when they see her on the street and invite her to hop in, or else they just take the time to look at her without asking for anything and then go back to what they were doing before. Mam Jeanne criticizes her for not knowing what to do with her beauty. And I continue to love her in contemplative silence. I miss our conversations. Before, she used to be full of theories and ideas. We would try to solve the world’s problems from my sidewalk curb. Now, we only talk to each other once in a while. That’s another thing I share with the little professor. We spend a lot of time looking at Joëlle. That’s another reason why he comes to the neighborhood. And when we’re discussing the tragic or bland fates that befall the heroines in our novels, she’s the one we’re really talking about, although we don’t dare refer to her by name. She’s with Wodné, who made his first suicide threat to her when he was eighteen. He walked around in the street with a vial that he claimed was filled with poison. We were all very frightened. Except Sophonie, who saw his actions as only the first instance of emotional blackmail. Sophonie has become a young woman with a strong body. She stopped going to college when Anselme’s illness reached an advanced stage. She’s a waitress at Kannjawou. Anselme is now confined to bed and isn’t all there anymore. In the evenings, after washing him and laying him down in clean sheets, his eldest daughter sets a glass of water on the bedside table, kisses him on the forehead, and says to him quietly as she’s leaving, I’m going to Kannjawou. He hears only the last word and believes that she’s planning a big party for him in the countryside where he grew up. The old man’s eyes begin to shine, and they say, Bring me. It will be the most beautiful of kannjawous. But exodus has replaced kannjawous. The people who lived there had enough of breaking their backs over a land that no longer gives them anything, so they left. And no one ever returns to the countryside. It’s not like in the legends that they used to soothe us with during our childhoods. The old people would tell us that the dead, tired of resting, would rise, take a little tour of the town, revisit the places they used to go, quickly grow weary of the world of the living, and return to take their places again in their tombs. The countryside is a tomb, and no one wants to be buried there alive. The countryside is like an old woman who’s been abandoned by all her descendants and who prattles on, all alone. The countryside is a place for hiking and parking for the Occupation soldiers, who watch over the goats and the cacti and who piss and shit in the rivers. They say that there are some who escape from their barracks to see the goats up close and embrace them, for lack of human lovers. The countryside is the evangelical missions, the pastoral part of the Occupation, who sell their god to the farmers in exchange for wheat and flour. The country-side is home to Halefort’s cousin, who’s known as Windward Passage. Seven times he took to the sea. Seven times the American Coast Guard brought him back. Today, he’s chosen to live in prison, and prefers never to come out if his other option is to return to the countryside. The countryside is a cemetery even vaster than ours, where humans, animals, and plants watch themselves die.

THERE IS NO LONGER A GANG OF FIVE. Our attempts to go out together always turn out badly. Wodné doesn’t drink alcohol and wants Joëlle to follow his example. There’s a silent command in his eyes, and Joëlle, half bravery and half cowardice, orders a beer that she doesn’t end up drinking. She’s more beautiful than ever, but she’s lost her impishness. Ever since Wodné’s suicide threat, they share a need for oaths that’s more solid than a wall. They’ve each finished their degree and want to continue with their studies. Soon it will be each for themselves in the race for a scholarship. That frightens Wodné. He’s afraid of the wall collapsing. Out of the five of us, he’s always been the most alone, ever since childhood. Living with an aunt who does nothing except pray and groan. Joëlle and Sophonie, Popol and me—we all came in pairs. Someone to argue with. To laugh with. He didn’t have anyone. And one day he came up to Popol and extended his hand. That’s how it is on Burial Street. When you can’t be alone any more, you choose a brother. A friend. In that way, we’re imitating the people who come to the cemetery to visit the grave of someone they hadn’t known before. A sort of post-mortem adoption. A stranger, chosen because of the flowers on his grave. Or because his name had a nice ring to it. Or just by letting chance dictate which tomb to stop in front of, this one rather than that one. And then they pray for the soul of the departed. You have to pray for someone, to connect with someone in order to feel less alone. Wodné was so lonely that one day, he came towards Popol, took a spinning top from his pocket, and said: Do you want to play with me? They’ve played together ever since. At friendship. At climbing onto the roof of Mam Jeanne’s house to fly kites. At activism and social consciousness. At being students, enrolling in the same university in order to take the same courses. But Wodné was so alone that even after he’d found companionship, he still felt loneliness. And the fear that comes along with it. And he clings to them, like glue. He acts as if he owns the people who are close to him. If you come too close, I’ll bite. Sophonie never forgave him for Joëlle’s tears during his first supposed suicide attempt. They barely speak to each other anymore. He barely speaks to me any more, either. He doesn’t like my sources of revenue. The students from private universities who sometimes give me their essays to write. I meet up with them at the Champ-de-Mars. They won’t come all the way down to Burial Street. Usually, the exchanges take place at the Place des Héros. I started during my senior year of high school. Ever since then, I’ve technically coauthored several theses, whose signatories have bragged about their knowledge in front of fancy committees. I don’t take these accomplishments seriously—they’re just to make ends meet. They allow me to learn about a wide variety of subjects, like the relationship between fiction writing and historical writing, or the difference between positive law and common law when it comes to cohabitation. Information, perhaps, for future novels. Wodné doesn’t care for it. I don’t know what offends him the most: that I’m doing work for people who are more fortunate than we are? That I’m speaking to them, which according to him is already too much complicitness? That a reader of novels is getting mixed up in scientific work? That what I write gets high grades from the most senior members of the college faculty? That in doing so, I’m proclaiming that I’m different from him? He and Joëlle form a radical couple who disapprove of many things. They refuse to speak to those who don’t come from Burial Street, like we do. To those who aren’t enrolled in any given humanities program. To those who belong to another generation. To those who don’t define themselves as “militants.” To those who belong to other groups of “militants”. This makes for a lot of people they won’t speak to. And Wodné doesn’t forgive me for my friendship with the little professor. They’re a united couple. But only when they’re together. When Joëlle is alone and comes to chat with the little professor and me, she acts much less dogmatic, and her eyes have some of the liveliness they did when she was a reckless child. The old spark appears there, making her seem younger. Mam Jeanne is right: everything is in the eyes. In the eyes of the little professor, when he’s looking at Joëlle, I can see praise and admiration. The rapture of someone who is looking at all the beauty in the world. In Joëlle’s eyes, the happiness of being loved. The marvelous reflection of her own light. As for me, I don’t count. We’ve known each other for forever. She’s used to my gaze and doesn’t find anything new in it. But the little professor came from far away to love her. As though he had wandered for a long time, as though everything he had lived before was only a long road that led him to her. I suppose that it’s a nice surprise, someone who comes to you and says, I am happy that you exist, apparently without asking for anything in return. Wodné still criticizes me for reading too many novels. It bothers him if I lend one to Joëlle. But sometimes people come to copy exactly the thing they hate. More and more, he has come to resemble Pasha, the character from Doctor Zhivago who speaks only in clichés and reprimands. We are all in books, living proof that the characters you find there really do exist. That by stripping off the disguises, you end up seeing who is who. The little professor and I spend a lot of time establishing the resemblances between living people and characters from novels. But the little professor never mentions Wodné. Out of tact.

THE PROBLEM IS THAT I HAVEN’T YET BEEN ABLE TO UNDERSTAND WHAT WODNÉ AND HIS “MILITANT” GROUP ARE FIGHTING AGAINST, NOR WHAT THEY STAND FOR. They only associate with each other, and their world is so small that there’s no room for any actions that include other people. When Sophonie had the idea for the Center, they weren’t crazy about it, even if Wodné did want to take charge of it right away. The gang of five didn’t really have a leader. And freedom is a form of distance. With time, Wodné created his own gang. They’re preparing. Everything they do is preparation. For what, I don’t know, but it will never happen. Two years ago, Popol and Wodné got in a fight. Both of them had bruises on their faces for months afterward. I know that it was Popol who threw the first punch. The whole street was shocked. The cobbler, the old bookbinder, the fried-food vendors, all of them tried to intervene. People called it blasphemy, sacrilege. It was as though Peter and Paul had thrown aside the Gospel and started hitting and kicking each other. Mam Jeanne had to come down into the street to put an end to the brawl. I never did ask Popol why he had broken his rule: never initiate an act of violence. With my brother, too, silence is part of our life. Popol has never been a talker. During our childhood, I used to annoy him by wanting to discuss what I’d read with him. At the end of a novel, I’d run to him to talk about the characters that had pleased or bothered me. About the hatred or affection that I’d come to feel for this or that one. What did he think about a son who abandoned his inheritance? A lover who couldn’t choose between rebellion and safety? He’d respond that he wasn’t the right person for that type of conversation. That he trusted me to find out for myself. He hasn’t changed. Still talks very little. Keeps his thoughts secret until they become actions, the meaning of which is always very clear. Wodné called a meeting so that he could rant about the poisoned chalices of the petty-bourgeois intellectuals. Sophonie wasn’t there. Everyone was waiting for Popol’s reaction. He contented himself with gathering the children together and helping them organize the books that the little professor had given them. End of meeting. Since he works a lot, I often correct his papers for him. I’m heavy-handed when it comes to syntax errors. Sometimes he asks me to revise my corrections. Not to be forgiving, but to be fair. We—the gang of five—were lucky enough to discover the power of language when we were very young. We stumbled upon words very early. But not all the boys and girls from streets like Burial Street had this experience. With all due respect to Wodné, who likes to think of us as the wretched of the earth, we’ve already gone to places that the others never will. Through words. Even without the extensive details and stories that fuel Monsieur Vallières’s ravings, even if for many subjects we’ve only skimmed the surface: however modest it may be, we have a place in the private club. We can discuss with the little professor, contradict him, correct him. We’re learning how to become the little professor, and Wodné never misses an opportunity to show him that we, too, can talk about serious philosophy and cultural revolution. I appreciate Popol’s silences. All those words that have become our passports, all those words that have made us the intellectual beneficiaries of the neighborhood—we haven’t yet learned how to make good use of them. For us. For the little kids of Burial Street. Mam Jeanne often tells us about the fortunes and misfortunes of the little kids like us who came from nothing, claiming to serve every good cause so that they could cash in on all of them. This or that elected official who had sworn by individual liberties and social justice before his election, and then afterwards opposed programs designed to fight illiteracy, confiding to those close to him the secret of his politics: if everyone from his hometown finally learned to read, what would become of him? We don’t know what to do with all these words. Halefort drinks a lot. The self-righteous and superstitious people from the neighborhood avoid him and tell their children not to respond to his greetings. They tell themselves that a graverobber attracts death, and a man who knows only how to desecrate tombs isn’t worth their acknowledgment. Halefort has a son with a woman who comes from a neighborhood even poorer than ours. The boy sometimes comes to see him. I suppose it’s whenever there’s nothing left to eat in the dumpster where he must live. Halefort will then give him whatever he has, and if he sees us pass by he asks us: “You guys, who know how to read, what are you planning to do so that my son won’t become a graverobber?” Popol grows quiet and waits to speak until he has an answer. Maybe he waits too long. Wodné quickly came to understand the power of making a fuss. If you start off by yelling, you’ll end up on top.

MY BROTHER AND I ONLY REALLY TALK ON WEDNESDAY EVENINGS. It’s the most crowded night, when the bar is open late. A flood of aid workers from all the Organizations-Without-Borders, allied countries, Occupation personnel, and young bourgeois are there. It’s a night of dancing and it lasts for a long time. We go together to wait for Sophonie, so that we can accompany her home after the bar closes. It’s all that’s left of the long walks of long ago. Of the lightness of times past. Going as a pair. And returning as a trio. Could it be that all the steps of our childhood—when Sophonie freed the lizards and dragonflies that Wodné had tied to a string; when we looked for hidden places in the sea where we could learn to swim, naked; when life was nothing but a big kannjawou, for Anselme, Mam Jeanne, the old people, the young people, all the Burial Streets and everyone from every corner of the world; when I learned from Wodné and Popol words whose meanings I didn’t know but which sounded like promises—were nothing but lost steps?

THERE ARE SOME EVENINGS WHEN MAM JEANNE CALLS DOWN FROM HER BALCONY TO INVITE THE LITTLE PROFESSOR AND ME TO COME UP AND HAVE SOME TEA WITH HER. To talk to us about the past. Mam Jeanne is the doyenne of Burial Street. Only the cemetery was born before her. In her stories, the past is all bric-a-brac. Everything is jumbled together. The time when women couldn’t enter the old cathedral without missals and mantillas, and would be pardoned for their adultery if they made substantial donations to the archdiocese treasury. The time of matinees at the Cinema Parisiana, tissues in hand for the tears brought on by an Italian actor, Amedeo Nazarro, who always played the son of a nobody and with whom all the young girls were in love. The time of the railroad, whose trains transported more cargo than passengers. The time when trees bloomed on Center Street, attracting turtledoves and wood pigeons, before the prison was built. The time when the Palais Orchestra performed on the Champ-de-Mars on Sundays, alternating waltzes, contra dancing, and military marches. In Mam Jeanne’s stories, the past will never be over. It will last for an eternity, distinct from the present. It’s difficult for her to match dates to facts. In order to recall the month or even the year, she has to think about it, count on her fingers. Except when she talks to us about the first Occupation. “There was nothing worse.” Not the yaws epidemic, when the disease attacked the feet and arms of the poor. In the countryside, no one dared any longer to clasp a friend’s hand, kiss his fiancée, drink from the same cup as his neighbor. Nor Hurricane Hazel. The crops and livestock carried away by the wind. The convoys of clothes and food sent to the flooded areas, which were held up for several days by the violence of the swollen rivers carrying trees and livestock. Nor the years that were unreasonably dry. The adults threw their hands up to the sky. And the children’s hungry eyes leaked tears of dust. “Yes, there was all of that. But the worst was when the boots came.”

HISTORY ISN’T ONLY MADE UP OF CATASTROPHES. In Mam Jeanne’s memories, there were also a lot of joyful times. In the past, there were plenty of kannjawous. “Circuses. Amusement park rides. Carnival parades, when those were still an attraction. With stilts as high as tall houses. Masks, both funny ones and not-so-funny ones: General Charles Oscar, bloodthirsty rapist, who died by the sword, just as he had lived. Beautiful Choucoune with the legendary ass, the mixed-race woman who had ruled over the hearts of the seaside shopkeepers, and who alone caused more suicides and bankruptcies than a financial crisis. Queens, each one prettier than the last. How beautiful it all was! The inauguration of the International Exposition. In ’49, I think. The singer Lumane Casimir, the most beautiful voice we had ever heard here. And the first jet of the illuminated fountain. The crowd was amazed and let out a cry of “Ah!” as though they had witnessed a miracle. The parade with horses. And the sports contests, the dances, the bursts of fireworks.” But the most beautiful of all was the departure of the Marines. “Even the funeral processions felt joyful. Here, on Burial Street, the children gave out sticks with ribbons attached that were the color of the flag, and the parents used them to decorate the coffins of their dearly departed. I don’t believe in ghosts, but it seemed to me as though there were songs of rejoicing coming from the great cemetery. Even the dead were celebrating that day.”

She says this, and is then overcome by sadness. They came back. This time, when they entered, they didn’t kill anyone. Not the little heroic soldier. Nor the rebellious farmers. Nor the ordinary citizens shot down by wayward bullets or drunken Marines who didn’t appreciate the muted anger in their eyes. They came back. They had meetings and conferences, agreements and resolutions made by do-gooder assemblies. They came back, with pretty spokespeople you could fall in love with. Men with crazy hair who don’t seem all that bad and who smoke joints with the other people their age. With little brunettes with wounded eyes who seem to be doing so badly that you want to feel sorry for them. But as Mam Jeanne says, “Foreign boots are foreign boots. On the ground, they’re all the same heavy footsteps.”

MAM JEANNE CLAIMS THAT IT’S A STROKE OF LUCK TO LIVE ON A STREET THAT ENDS WITH DEAD PEOPLE. It makes you learn very quickly how to distinguish what is real from what is false. Every day there’s a parade before us of dead people sealed up in their coffins. We don’t see their faces. But we see the faces of the living people who accompany them. And Mam Jeanne wants the things that are happening in your heart to show up on your face. According to her, even the most naïve of kids can see, if he looks closely, which widow’s face is covered in real tears for a useless dead man whom she nevertheless continues to love. Which loved ones or friends are focused on something else and finding the time slow to pass. Which group of dice players knows that for all of them their luck has just changed, that from now on life is nothing but a slow slip into death, the partner that they’re burying only the first in a long series. Which screams from a prodigal son ring false, and are all a sham.

LOOKING CLOSELY, YOU CAN SEE THAT JOËLLE DOESN’T HATE THE LITTLE PROFESSOR. In fact, she’s the only one to call him by his first name, Jacques. And in the evenings, she comes to join our conversation, faking a nonchalant walk that doesn’t hide the fact that she’s hurrying. Only for a few sentences. I give them a moment alone, claiming to have an errand to do in the neighborhood or some work to finish. It’s crazy how much she looks then like the little mischievous girl who, almost twenty years ago, on one July morning, had suggested that we go see the hurricane up close. Anselme already wasn’t walking too well at that time, but he was managing okay with his cards. He was still feeding his children by selling the future to people begging for miracles. He was getting out of bed only to receive clients. His cards next to him on the bedside table, he believed strongly in the power of speech. He expected the things he said to come true as much as his clients did. Disappointed clients sometimes returned to him with insults and demands for reimbursement, as his quack predictions had never materialized, or the opposite had come true. The pretty woman he had predicted would come to the lonely man hurting for love had turned out to be a shrew. The handsome man actually a bully. Wealth actually grinding poverty. This or that announced trip had turned into a never-ending wait, despite the sums of money paid to myriad brokers and officials. He gave the money back with excuses. Reality had lied. For Anselme, words create the world. It was enough for him to say, “One day, I’ll get my land back and we will have the most beautiful kannjawou, my daughters,” then wait for the day to arrive. Sophonie was skeptical. Anselme hadn’t seen Immacula’s death, nor the more ordinary problems, coming. He couldn’t see that he would never manage to take back the land that had been taken from him by shady lawyers and the henchmen of whatever despot had been in power at the time. That his daughters weren’t farmer princesses at all, and would have to fight to survive. That even if these mythical lands did exist, they wouldn’t know what to do with them. That they were daughters of Burial Street, second-class citizens who would know neither sowing and harvest nor the luxuries of hilltop mansions. Anselme hadn’t seen the occupiers’ boots coming, nor the civilian staff who would go drinking at Kannjawou. A seer who had been struck by blindness. A fallen wealthy farmer who had failed on Burial Street. But Joëlle believed in her father’s predictions. Gullible little girls don’t listen to the news. To convince her of his powers, he informed her of what everyone else already knew: that a hurricane was coming. “Tomorrow. Don’t be scared. You see, your father knows everything that is to come.” Wind wouldn’t do any harm to his children, especially not to his favorite one. And so according to Joëlle, who was firm in her convictions, we could go see the hurricane up close. And even if it might be risky, it would be worth it to see what was in the middle of the wind. I loved that expression: in the middle of the wind. I had written it down in my notebook, and sometimes, to remember the gang of five, I reopen that notebook to the page with the middle of the wind. Wodné didn’t think that it was wise to go see the hurricane closer up. Popol didn’t say anything. Joëlle insisted. It’s not good to be afraid. Sophonie decided that we would go, to please her little sister. And also to defy Wodné. We went out into the street. The wind struck us in the face, but we could still see the outlines of each house and walk in the rain. In the beginning it was very pleasant. If that’s what they call danger… But then, very quickly, the wind pushed us in the direction of the cemetery. Impossible to resist, to choose our own path, to turn back. The wind brought us to where the dead were resting. The left-hand side of the great gate had been ripped away and was being pulled towards the inside of the cemetery as though it were as light as a feather. The water ran and covered the pathways. The new tombs, whose cement hadn’t yet fully dried, had turned into little ponds. When the middle of the wind arrived, it was a frenzied madness that left nothing in its wake and swept everything on the earth up towards the sky; the water that came crashing into our eyes made the horizon disappear. Groping for shelter, we hid in an unlocked vault that had been under construction. Together, holding each other’s hands, we held the gate in place. In front of us floated coffins that looked like crazy boats. We waited. Fortunately, the middle of the wind was moving. After several hours, it left to go elsewhere. We walked in the mud and rain, trying to avoid stepping on the bodies and thousands of objects that the storm had lifted from their tombs. The hurricane had done more in several hours than Halefort’s gang had in years. We didn’t want to split up or go to Wodné’s aunt’s house or to the girls’ house, where Anselme was probably asleep and dreaming of kannjawou, or to our house, where in any case there weren’t any adults. So we took shelter in Mam Jeanne’s house, spending the night there. Joëlle hadn’t trembled or whined. She’d wanted to see and she had seen. We had gone into the middle of the wind and we came back out again. It’s that Joëlle that I leave in the little professor’s company in the evenings. A little girl with lively eyes, asking to see. Their conversation never lasts very long. Wodné is always there, watching over them. Joëlle rejoins him silently. Then I walk a little longer with the little professor, up until College Street. Then I go on my own way. We walk in opposite directions, but the ends of our nights are similar. It’s the time when we become our dreams and spend a long time with characters from books. If we must, as Wodné says, always find a difference, it’s just that the little professor has more characters in his house than I do in my room.

IS WHAT IS TRUE FOR PROCESSIONS ALSO TRUE FOR BARS? Seated on the low wall that borders the courtyard of kannjawou, I like to observe the clientele. On Wednesdays, when Popol and I go to wait for Sophonie, Monsieur Régis, the owner of the bar, allows us to sit on the wall and have one beer each. He’s not a bad guy. The staff members like him. He has a sense of humor. “With what I charge my clientele, I can afford to give you a beer.” It’s the third bar that he’s opened. The first two didn’t work out very well. After those two failures, he learned. A residential neighborhood. A name that’s a little mysterious: “Kannjawou”. Shadowy corners. Music that they’ll like. Wait for the first foreigner. “Since they’re all attracted to the idea of being an explorer—we’ve known that since Christopher Columbus—the first one will bring another. The second will bring a third. Life is good in the New World.” Monsieur Régis is a beefy guy, a force of nature with a tendency to gain weight and go running on Saturdays. “A restaurant owner shouldn’t be either too fat or too thin. Too fat, you look sleazy. Too skinny, you look stingy. I like to stay between the two.” His wife’s name is Isabella. She calls him on the phone twenty times every night, and he responds that he should have done as his best friend, who lasted only a week in the bonds of marriage, did. Go far away, like Christopher Columbus did. Because it’s no treat to answer the same questions every evening. “How many patrons tonight? Are the servers looking presentable?” Nor is it fun to live under such financial surveillance. Monsieur Régis doesn’t have a cent to himself. “It’s Isabella who holds onto the money. Because of her name, she thinks she’s a queen. And she’s Catholic, as the other Isabella was. Except that unlike King Ferdinand, I have no ships, I’ll be forever in debt thanks to this bar, and no one’s yet offered to make me a saint.”

From our wall, we watch Sophonie fuss around, going from one table to the next, smiling at her customers, pretending not to notice our presence. “At the bar, I’m working. The smiles are for the customers.” This is what she says. But most of the customers don’t even notice that she’s smiling at them. She serves them drinks at least once a week, but when they pass her in the street they don’t recognize her. It doesn’t matter. Sophonie has always done things just because they seem right to her. Necessary. This job is for Anselme. And for Joëlle, who will show them. So, no matter if the customers can be crude. And all things considered, there’s little chance that she’ll run into any one of them anywhere but the bar. After closing time, they head out in groups towards their apartments or houses in chintzy neighborhoods, at the wheels of their cars, which are draped in the colors of international institutions or NGOs. Their journeys will end at the top of some hill or another. And not a sad, ramshackle hill, shaking with the coughs of tuberculosis, like the ones that loom over the cemetery and shelter the sanatorium, where the poor people who are going to die from some contagious disease are hidden away. Nice hills, with their own names that start with “Belle”—Bellevue, Belleville—at the end of a private street, protected by sentry boxes, watchdogs, and security guards. They come down to the bar to slum it. Outside of those escapades, many of them only know the upper part of the city. That expression, the upper part of the city, comes from one of the bar’s customers, one of the few with literary alcoholism: he tends to rhapsodize about literature whenever he drinks. Monsieur Vallières, who thinks his ravings are an important piece of work, he says that, like the human body, cities are divided in two parts: upper and lower. The problem is when the line of demarcation is lost. “Tell me. Can you still tell who is who here?” He drinks too much and talks a lot. Words tussle with each other in his mouth. Too many things come out at the same time. Bickering. Contradicting each other. They say he failed at his career as a Latin scholar. Thanks to a family inheritance, he owns a store that he runs in the old-fashioned way, to the great despair of his sons. In his family, he plays the role of intermediary between his father, who imposes his will with the power of his legacy and his strength of character and who had wanted his son to become a man of great refinement, and his sons, unsophisticated bloodsuckers whom he refers to as garbage. The bar is his theater. Strangely enough, it’s also a form of resistance for him. He often raises his voice. This bothers the younger members of the Occupation staff, who don’t like to hear any voices other than their own and the racket of the music they’re dancing to. He looks at them and shouts, “Aren’t I at home here?” Monsieur Régis likes him very much and sometimes sits down at his table. Monsieur Vallières takes advantage of this when it happens, retelling his memories as an egghead and a scholar. Literature, fancy language. Entire pages of Historia. The Renaissance, revolutions, Genghis Khan and Mata Hari. The other customers, the younger ones—aid workers, or children of wealthy parents—avoid him and don’t talk as much, or in any case not about things like the Renaissance, revolutions, Genghis Khan and Mata Hari. Wodné would say that Monsieur Vallières is an old bourgeois, distrusted by young people because he hasn’t learned how to adapt to modernity. I personally believe that at the rate they’re drinking, they’re running away from him because he looks like he could be their future. At least, if any of them know how to read things other than relationships and instructions. For lack of an audience, he sometimes invites us to sit with him at his table. Even if you’re rich and cultured, you do what you can with what you have. Two little guys from Burial Street might be interesting and make very nice substitutes if the only other audience you have is the least sophisticated members of the middle class and arrogant technocrats, the civil arm of the Occupation. His madness makes him pragmatic. Although Popol and I are only pretending to listen to him, Monsieur Vallières appreciates the company of us representatives of the “lower parts”.

YES, MAM JEANNE, WE ARE ALL WRONG ABOUT SOMETHING. It’s persisting in that wrongness that makes even the strongest emotion collapse into pretense. This is true for the little brunette who comes to the dance floor of Kannjawou every Wednesday for the wrong joy and pain. Just as it applies to the people we call the Bewildered, every Saturday morning. On Saturday mornings, the ultimate day of the dead, hearses line up one after the other on Burial Street. Latecomers and hotheads therefore don’t know which convoy is which, and wind up accompanying a corpse they hadn’t known to the tomb. I don’t count Monsieur Pierre, a retired public-service worker who comes every Saturday to accompany the dead. Malicious gossipers say that he’s obsessed with numbers and statistical problems. Accompanying the departed to their tombs is a mental exercise and a nice healthy walk for him. If that’s the case, Monsieur Pierre doesn’t want to make a mistake on his accounting. But there are people who stupidly pick the wrong procession. By the time they realize they’ve made a mistake, they’re suffocating in a crowd of strangers. The most determined of them will take the risk of offending someone and make their way to the sidewalk, sputtering excuses. If their procession is far behind, they’ll find a shadowy corner in which to wait so they can slide in when it passes by. If it had already gone by, they’ll hurry forward, almost running in their funeral clothes, in order to catch up to their group before the last shovelful of dirt is placed on the coffin. The ones who lack courage or are simply more polite don’t dare to disturb the mood. Offering their arm to an inconsolable old woman begging for support or listening to the confidences of the chatty people who want to brag about their relationship to the dead, they follow the wrong procession up to the cemetery entrance and then slip away discreetly before the speeches begin.