[1]

INNER EURASIA IN THE LATE THIRTEENTH CENTURY: THE MONGOL EMPIRE AT ITS HEIGHT

THE WORLD IN 1250

First it should be known that in every clime of the world there have been and are people who dwell in cities, people who live in villages, and people who inhabit the wilderness. The wilderness dwellers are particularly numerous in territories that are grass lands, have fodder for many animals, and are also far from civilization and agricultural lands.1

In 1250, human societies were still divided into zones so disconnected that they could almost have lived on separate planets. Human communities in Afro-Eurasia, the Americas, Australasia, and the Pacific had barely any contact with each other.

Of these world zones, the Afro-Eurasian zone, reaching from the Cape of Good Hope to northeastern Siberia, was by far the largest, had the most people, the greatest variety of cultures, cuisines, and technologies, and enjoyed the most vibrant exchanges of goods, peoples, ideas, and even diseases. These exchanges were most vigorous within the densely populated agrarian societies of Outer Eurasia, from China through South-East Asia, to India, the Middle East, North Africa, the Mediterranean region, and Europe. But increasing exchanges also forged connections through the southern parts of Inner Eurasia, along the so-called Silk Roads.2 Many of these connections were created by regional pastoralists and traders. But they flourished best when Outer Eurasian empires that bordered on Inner Eurasia, such as China or Persia, became interested in long-distance trade through the region, and protected merchant caravans or sent caravans of their own, or when powerful Inner Eurasian empires tried to tap the wealth of neighboring regions of Outer Eurasia, or when both types of polities existed simultaneously.

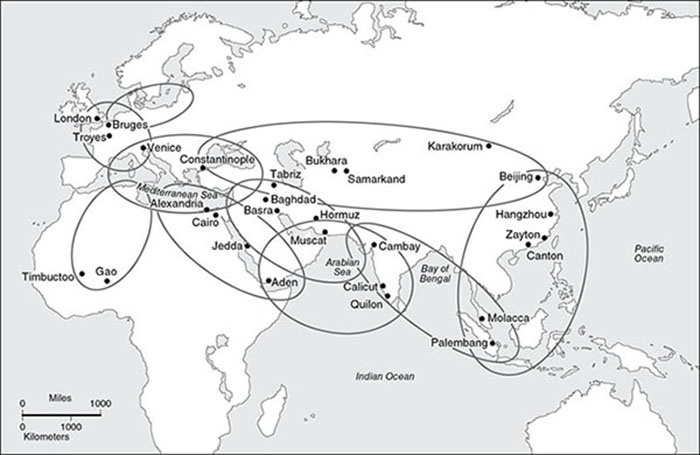

Since the first millennium BCE, such mechanisms had driven several pulses of trans-Eurasian integration. At the start of the Common Era, large empires in Han China, Persia, and the Mediterranean, and steppe empires such as the Xiongnu in Mongolia, or borderland empires such as the Kusana in modern Central Asia and Afghanistan, synergized transcontinental exchanges. A second integrative pulse coincided with the rise of Islam from the seventh century CE.3 It linked powerful empires in the Mediterranean region, Persia and China, with Turkic steppe empires. In the thirteenth century, the Mongol Empire emerged during a third integrative pulse, and helped create long-distance exchanges more vibrant than ever before.4 Janet Abu-Lughod has argued that this pulse created the first Afro-Eurasian “world system,” by briefly linking eight regional networks of exchange into a single system (Map 1.1).5

Map 1.1 Abu-Lughod map of Afro-Eurasian trade circuits prior to 1500. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony, 34. Reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press.

The globalizing pulse of the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries networked more of Afro-Eurasia more powerfully than ever before. In Inner Eurasia, with its scattered populations and limited surpluses, new flows of wealth could have a spectacular impact. Here, they jump-started political, economic, cultural, and military mobilization in a sort of “sparking across the gap.”6 The Mongol Empire's Chinggisid rulers understood what vast arbitrage profits could be made by moving goods such as silk or tea or silver, which were rare and expensive in one part of Eurasia but common and cheap in another, and many Mongolian leaders, including Chinggis Khan's own family, formed profitable trading partnerships, or ortoq, with Central Asian merchants.7 These yoked the financial and commercial expertise of Central Asian cities and merchants to the military power of Mongol armies, in alliances that mobilized what were, by Inner Eurasian standards, colossal amounts of wealth.

By protecting trans-Eurasian commerce, Mongol rulers encouraged travel and trade along the Silk Roads. For the first time in world history, many individuals crossed the entire continent. They included Marco Polo, the Mongol soldiers and commanders who campaigned from Mongolia to eastern Europe, and the Nestorian Christian missionary Rabban Sauma, who left northern China for Persia in about 1275, before traveling to Rome and Paris as an ambassador of the Mongol ruler of Persia, the Il-Khan.8 In about 1340, Francis Balducci Pegolotti, an agent of the Florentine mercantile company of the Bardi, compiled a handbook for Florentine merchants, which asserted confidently that, “The road you travel from Tana [modern Azov] to Cathay is perfectly safe, whether by day or by night, according to what the merchants say who have used it.”9 At about the time that Pegolotti's guidebook was published, the Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta accompanied caravans from the Black Sea through the Pontic and Khorezmian steppes to Central Asia and on to India. He may have traveled to China before returning to his native Morocco and making one final trip across the Sahara.10

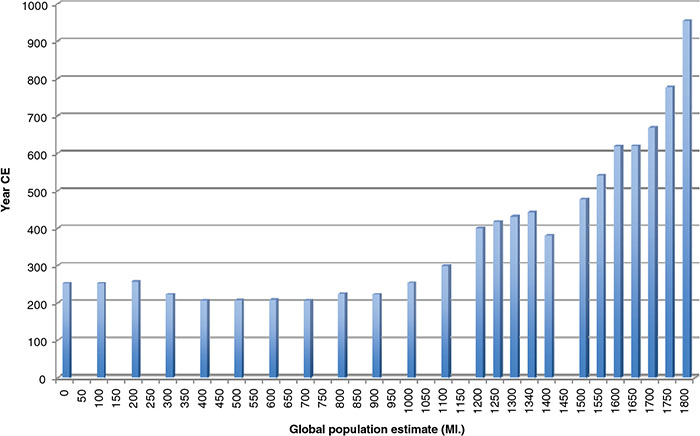

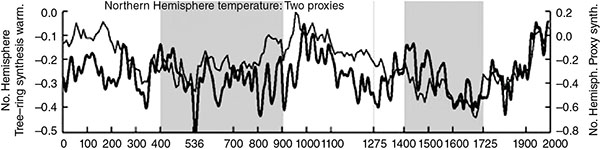

Warmer climates and several centuries of demographic growth helped drive the thirteenth-century pulse of integration. Particularly in previously underpopulated regions on the borders of major agrarian regions, populations rose fast from late in the first millennium CE, as peasants migrated down the demographic gradient into underpopulated regions in southern China or western Inner Eurasia, bringing new technologies and new crops or crop varieties, and driving commerce and urbanization (Figure 1.1). According to McEvedy and Jones, the population of Outer Eurasia changed little between 200 and 800 CE, by which time it was 180 million.11 Then growth picked up. By 1000 CE, 215 million people lived in Outer Eurasia, and by 1200 CE, 315 million. In much of Eurasia, population growth may have been linked to the generally warmer and wetter climates of the “Medieval Climate Anomaly,” which John L. Brooke dates to 900–1275.12 During this period northern hemisphere temperatures were on average more stable and warmer than they would be again until the twentieth century (Figure 1.2).13

Figure 1.1 Global populations over 1,800 years. Brooke, Climate Change, 259. Reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Figure 1.2 Climate change 1 CE to 2000 CE. Brooke, Climate Change, 250. Reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press.

The Medieval Climate Anomaly played out somewhat differently in Inner Eurasia. Here, it generated long periods of drought and cold from 1000 CE until the late fourteenth century. These bleak conditions provide the background to the civil wars of Chinggis Khan's youth, as they limited livestock levels and impoverished pastoralists. Climates were particularly cold during the 1180s and 1190s. However, recent tree-ring evidence suggests that there was a brief period of exceptionally wet conditions in Mongolia between 1211 and 1225, during which expanding grasslands allowed livestock herds to multiply, fueling the explosive growth of the Mongol Empire under Chinggis Khan.14 But colder, drier conditions returned to Inner Eurasia for much of the thirteenth century, after which humidity increased in the late fourteenth century, reaching a peak between 1550 and 1750.15

Demographic information for Inner Eurasia is even less reliable than for Outer Eurasia. However, except for brief periods of growth in livestock populations, it is unlikely that there was sustained long-term growth in the steppe zones, because pastoral nomadic societies had probably reached their maximum carrying capacity as early as the first millennium BCE, after which there remained no unused regions of steppeland.16 Growth was also limited in the oases of Central Asia, where deserts limited the farmable area, while irrigation agriculture could flourish only in periods of political stability and under rulers who maintained and extended irrigation canals. However, in the agrarian fringes of Inner Eurasia, along the western borderlands of Kievan Rus’, populations probably did increase. Here, peasant farmers from eastern Europe brought new lands into cultivation, often under the protection of new regional principalities. Even here, though, a combination of arid conditions, poor forest soils, and warfare during the Mongol invasions probably slowed growth in the first half of the thirteenth century.

The figures of McEvedy and Jones suggest that the population of Inner Eurasia grew from about 9 million in 800 to about 12 million in 1100 and 16 million in 1200 (when the population of Outer Eurasia was about 315 million). Then growth slowed, rising to just 17 million by 1300. Most of this growth was probably in the agrarian lands of Kievan Rus’. The different population histories of different parts of Inner Eurasia mark the beginnings of a belated agricultural invasion of Inner Eurasia that would eventually transform the entire region.

KARAKORUM: THE MONGOL EMPIRE AT ITS APOGEE, AND A PUZZLE

Mongol power was at its height between 1250 and 1260. In the late 1250s, Khan Mongke ruled the largest land empire that had ever existed (see Figure 0.2). His authority reached from eastern Europe to the newly conquered regions of Persia (the Il-Khanate), to Central Asia, Xinjiang, Mongolia, and northern China. No single ruler would control such a vast area again until the late nineteenth century, when the Russian Empire ruled slightly less territory than Mongke.

As remarkable as the Mongol Empire's size was the speed of its creation, a story told in Volume 1 of this history. Andrew Sherratt's metaphor of “sparking across the gap” is apt here, with its hint that in regions of limited human and material resources such as Inner Eurasia, weak external charges can spark explosive change. In any case, pastoral nomadic communities were inherently unstable. Sudden outbreaks of disease, or the climatic shock known as dzhut (which covered grass with ice so that herds starved to death) could destroy herds and ruin families and clans in days. Instability was guaranteed by the constantly changing relationship between natural resources (above all grasslands and water), the size of herds, and the size of human populations. Sudden changes in any of these factors could ignite wars over pasturelands and herds because, since the middle of the first millennium BCE, there were no remaining reserves of pasturelands. Local wars, in turn, could cascade into large military mobilizations and long-distance military migrations with the formation of regional military alliances.17

In 1150 CE, Mongke's grandfather, Temujin, the founder of the Mongol Empire, was an outcast in a Mongolia torn apart by vicious civil wars. Half a century later, in 1206, Temujin assumed the title of Chinggis Khan, becoming supreme ruler of the Mongols and their many allies. At his death in 1227, Chinggis Khan's empire reached from northern China to Central Asia. Juvaini, a Persian who served the Mongols and visited their capital, Karakorum, in 1252–1253, knew individuals of Chinggis Khan's generation who had lived through these astonishing years. He described their experiences in typically flowery language:

they [the Mongols] continued in this indigence, privation and misfortune until the banner of Chingiz-Khan's fortune was raised and they issued forth from the straits of hard-ship into the amplitude of well-being, from a prison into a garden, from the desert of poverty into a palace of delight and from abiding torment into reposeful pleasances; their raiment being of silk and brocade, … And so it has come to pass that the present world is the paradise of that people…18

Karakorum, the empire's capital from 1235 to the 1260s, provides an apt symbol of these astonishing changes. It was built near the Orkhon river, in a region fertile enough to support some agriculture. Many khans had built their winter camps here, and some had built imperial capitals. The area had been sacred to the Xiongnu in the second and first centuries BCE, to the Türk in the sixth and seventh centuries CE, and to the Uighurs in the eighth and ninth centuries.19 Chinggis Khan understood and valued the region's imperial traditions, for many Uighurs served him, so he knew that the Uighur Empire had built a capital nearby at Karabalghasun/Ordu-Baligh. Before settling on Karakorum as his own winter camp in c.1220, Chinggis Khan surveyed the old Uighur site and found a stone stele, inscribed in Chinese with the name of the third Uighur emperor, Bogu kaghan (759–779). In 1235, Chinggis Khan's heir, Ogodei, recruited a Chinese official, Liu Ming, to start building a capital with mud walls, permanent buildings, and a complex of royal palaces (Figure 1.3).20

Figure 1.3 Karakorum. Reconstruction of Ogodei's palace, from a University of Washington site. Courtesy of Daniel C. Waugh.

Karakorum grew like a gold rush town. Oceans of wealth arrived as military booty or with trade caravans. Fortunes were made and lost with such dizzying speed that commercial rules lost all meaning. Juvaini writes:

At the time when he ordered the building of Karakorum … [Ogodei] one day entered the treasury where he found one or two tümen [thousands] of balish [gold ingots]. “What comfort,” he said, “do we derive from the presence of all this money, which has to be constantly guarded? Let the heralds proclaim that whoever wants some balish should come and take them.” Everybody set forth from the town and bent their steps towards the treasury. Master and slave, rich and poor, noble and base, greybeard and suckling, they all received what they asked for and, each having obtained an abundant share, left his presence uttering their thanks and offering up prayers for his well-being.21

People as well as goods flowed towards Karakorum: merchants, ambassadors, princes, priests, and soldiers, and also captives. The Mongols mobilized vast numbers of captives, most of them artisans, from all parts of the empire, and, despite its remote location, Karakorum became remarkably cosmopolitan.22 The Franciscan friar William of Rubruck, who visited in 1254, met people from China and Korea, from Central Asia, Turkey, and Europe.23 But Rubruck was not impressed with the city itself, perhaps because he had lived in Paris. “[D]iscounting the Chan's palace,” he wrote, “it is not as fine as the town of St. Denis.”24 Even when the khan was in residence with all his followers, Karakorum's population was probably less than 15,000.25 Marco Polo visited in the early 1270s (10 years past its prime) and described it as three miles in circumference and “surrounded by a strong rampart of earth, because stones are scarce here.”26 Beyond its two main streets, which have been excavated by Soviet and Mongolian archaeologists, most of its dwellings were probably tents.27

Despite its size and remoteness, for a few years Karakorum acted as a capital for much of Eurasia. In August 1246, leaders came from all parts of Eurasia to the quriltai that elected Khan Guyug as the empire's third supreme ruler.28 Juvaini, who first visited Karakorum just six years later, provides a glittering roll call of this international gathering:

when messengers were dispatched to far and near to bid princes and noyans [Mongol lords] and summon sultans and kings and scribes, everyone left his home and country in obedience to the command. … Sorqotani Beki [mentioned first, presumably because she was the mother of Juvaini's boss, the Persian Il-Khan] and her sons arrived first with such gear and equipage as “eye hath not seen nor ear heard.” And from the East there came Köten with his sons; Otegin and his children; Elchitei; and the other uncles and nephews that reside in that region. From the ordu of Chaghatai [Chinggis Khan's second son] came Qara, Yesü, Büri, Baidar, Yesün-Toqa and the other grandsons and great-grandsons. From the country of Saqsin [Saray, on the Volga delta, Batu's capital] and Bulghar, since Batu did not come in person, he sent his elder brother Hordu [khan of the “Blue Horde” in the Kazakh steppes] and his younger brothers Siban, Berke, Berkecher and Toqa-Timur [all of whom we will meet later; now we move to sedentary regions of Inner and Outer Eurasia]. From Khitai [China] there came emirs and officials; and from Transoxiana and Turkestan the Emir Mas'ud [the son of Mahmud Yalavach, whom we will also meet] accompanied by the grandees of that region. With the Emir Arghun there came the celebrities and notables of Khorasan, Iraq, Lur, Azerbaijan and Shirvan. From Rum [Anatolia] came Sultan Rukn-ad-Din and the Sultan of Takavbor; from Georgia, the two Davids; from Aleppo, the brother of the Lord of Aleppo; from Mosul, the envoy of Sultan Badr-ad-Din Lu'lu; and from the City of Peace, Pabhdad, the chief cadi Fakhr-ad-Din. There also came the Sultan of Erzerum, envoys from the Franks [probably a reference to the mission of the Franciscan, John of Plano Carpini], and from Kerman and Fars also; and from ‘Ala-ad-Din of Alamut, his governors in Quhistan, Shihab-ad-Din and Shams-ad-Din.29

The gatherings at which Chinggis Khan's three successors were enthroned (in 1229, 1246, and 1251) were perhaps the most international meetings of leaders before the twentieth century: the thirteenth-century equivalents of meetings of the United Nations. But deep in the Mongolian steppe, it was not easy to support such numbers. According to Juvaini:

this great assembly came with such baggage as befitted such a court; and there came also from other directions so many envoys and messengers that two thousand felt tents had been made ready for them: there came also merchants with the rare and precious things that are produced in the East and the West. When this assembly, which was such as no man had ever seen nor has the like thereof been read of in the annals of history, was gathered together, the broad plain was straitened and in the neighbourhood of the ordu there remained no place to alight in, and nowhere was it possible to dismount. … There was also a great dearth of food and drink, and no fodder was left for the mounts and beasts of burden.30

How was it possible to generate such power in an environment of such scarcity? The Mongol Empire raises this puzzle in an acute form. But the puzzle is more general and applies to the whole history of Inner Eurasia. Why did the world's largest contiguous empires appear in this region? How did the Mongol Empire, the Russian Empire, and eventually the Soviet Union mobilize such power and wealth despite Inner Eurasia's ecological limitations?

Answering that puzzle will be one of the main tasks of this volume. The rest of this chapter will focus on the mobilizational strategies and methods used by pastoral nomadic polities like the Mongol Empire.

SOME RULES OF MOBILIZATION IN INNER EURASIA

The mobilization systems that emerged in Inner Eurasia can seem puzzling because so many of our ideas about mobilization and state formation are derived from the study of agrarian polities in Outer Eurasia.

In agrarian regions, the rules of state formation are well understood. It was not difficult mobilizing resources from peasants because peasants everywhere are tied to their villages, and weakened by geographical dispersion, limited education, and resources. So the main challenge for elites keen to “feed on” peasant resources was to build mobilizational structures just strong enough to extract labor and resources household by household or village by village. Coercion always played a significant role, so elites had to have disciplined groups of enforcers that could back up the demands of local tax collectors or overlords. But to deal with individual villages, these groups did not need to be large. However, coercion rarely worked on its own. Elites claimed legitimacy for their fiscal claims by aligning themselves with systems of religious belief or rule that justified their authority. They also offered protection for households and land. And, as so many traditional “how to rule” manuals insisted, it made sense to limit fiscal demands, both to earn the gratitude of peasants and to ensure they lived well enough to keep producing and paying year after year. Where agrarian populations were large, and elite groups were organized over large areas, such methods could mobilize enough people and resources to build imperial armies and magnificent cities, to support wealthy aristocracies, to engage in international trade in luxuries, and all too often, to mobilize the resources and people of neighboring regions through warfare and conquest.

It is because these rules seem so obvious that the rather different rules of mobilization in traditional Inner Eurasian societies can seem puzzling.

In the first place, resources were more scattered in Inner Eurasia, in contrast to Outer Eurasia, where they were concentrated conveniently in barns, villages, towns, and cities. In Inner Eurasia, would-be mobilizers had to mobilize people, animals, and resources scattered in small denominations over large areas. State-building was the political equivalent of a livestock muster. To mobilize over large areas, mobilizers had to be mobile. Like pastoral nomads and their livestock, they had to do a lot of grazing over large areas, and their grazing had to be coordinated over vast distances. Indeed, the larger the area the better, as more grazing meant more resources, so that advantages accumulated to large systems, in distinctively Inner Eurasian economies of scale. This powerful feedback cycle helps explain why Inner Eurasia, despite its limited human and material resources, was home to the largest contiguous empires ever created.

Where land was abundant and people scarce, mobilizers focused on people and animals, rather than land. This is why, for leaders such as Chinggis Khan:

human capital was of primary importance … and the political struggles that accompanied the formation of the Mongol state concentrated on the control of people and herds rather than territorial gains. The demographic imbalance also meant that in order to continue to expand, the Mongols had to make use of the already conquered (and submitted) subjects. The first and perhaps most wide-ranging means for Mongol mobilization was therefore the army.31

Agriculturalists in Inner Eurasia would come to share similar ideas on mobilization. In 1763, a Russian noble, Count Zakhar Chernyshev, wrote, “[A] state is able to support its army not through the extensiveness of lands, but only in proportion to the people living in them and the revenues collected there.”32

MOBILIZING RESOURCES IN THE STEPPES

Pastoralist societies used distinctive mobilizational strategies that arose from their distinctive lifeways. Unlike peasants, pastoralists were highly mobile. They grazed their animals over large areas, and they were used to controlling and directing the movements of large animals. In short, they were good at rounding up scarce calories over large areas. Inner Eurasian pastoralists traditionally used five main species of livestock: horses, cattle (or yaks in highland regions), sheep, goats, and camels. Around these animals there developed entire lifeways that included the use of tents made from wooden frames, usually covered with felt (gers in Mongolian or yurts in Turkic languages), regular, well-understood and controlled migration routes, and a clear division of labor by gender, age, and rank.33 So well adapted were these lifeways to the steppelands of Inner Eurasia that many of their features have survived today in parts of Central Asia and Mongolia.

The construction of the ger – and the organization of domestic space within it – today is virtually indistinguishable to that described by William of Rubruck and Marco Polo in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. … The uurga pole-lasso, the making of airag (fermented mares’ milk), and a whole range of other current pastoral techniques date back to the thirteenth century at least.34

Mobilizing resources from pastoralists was harder than mobilizing from peasants. Pastoralists could flee easily, they were good fighters, and they generally had few resources apart from their herds. But mobilizing armies of pastoralists was relatively easy. Pastoral nomadic lifeways trained everyone in the handling and hunting of large animals and the skills needed to navigate over large distances and survive in the steppes, while constant petty feuds over pasturelands, livestock rustling, or vengeance for crimes provided regular training in combat.35 Forming armies was much easier and cheaper in the steppelands than in agrarian regions.

Those armies could be used, in turn, to mobilize resources from neighboring agrarian regions. In the ninth century CE, a Chinese official noted:

for us to mobilise our forces would take at least ten days or a few weeks, while for them [the Uighurs] to take our men and animals prisoner would take at most a morning or an evening. By the time an imperial army could get there, the barbarians would already have returned home.36

In summary, forming armies was cheap and easy in the steppelands, but mobilizing resources was difficult, because they were scarce and scattered; whereas in agrarian regions, there were plenty of resources and people, but forming armies was complex and expensive because peasants lacked military skills.

These differences explain why, in the pastoral nomadic world, mobilization began with the formation of armies rather than with the collection of resources to pay for armies. And forming pastoralist armies began with the ties of kinship and tradition that structured pastoral nomadic societies. Households were embedded within systems of rank and lineage, of clans and family groups, that controlled the allocation of pasturelands and adjudicated disputes.37 Where military skills were almost universal, building small raiding parties was easy, because the same leaders who allocated pasture routes could also summon young men for combat. But raiding parties allowed little more than the odd booty raid. Building larger mobilizational systems in the steppes was a more complex operation, and involved two further steps: binding smaller armies into larger armies, and finding resources worth a significant mobilizational effort.

Linking armies required difficult negotiations between local and regional leaders, to create leadership structures that could coordinate the activities of separate armies over large areas. Such negotiations could only work if the rewards seemed substantial, so building military alliances and identifying promising mobilizational targets went together. For pastoral nomads, the most promising targets were neighboring agrarian regions, where resources were more abundant and diverse than in the steppes. This helps explain the geography of pastoral nomadic mobilizational systems, most of which emerged in a zone along the southern fringes of Inner Eurasia, from the Ordos in northern China, through Central Asia to the Pontic steppes. Here, pastoral nomads could mobilize from nearby agrarian regions or cities or trade routes. As Thomas Barfield has shown, using steppe armies to mobilize from agrarian regions was the preferred strategy of all Inner Eurasia's most powerful pastoralist empires. (See Map 1.2.)38

Map 1.2 The zone of ecological symbiosis. Adapted from Encarta.

The techniques used by pastoralists to mobilize resources from agrarian regions became increasingly varied and sophisticated over 2,000 years. At their simplest, they took the form of crude booty raids whose destructiveness made long-term mobilization impossible. But over time there appeared systems of regular, sustained tribute collection, often combined with lucrative trading relationships. These more restrained methods of mobilization could evolve into formalized systems of tax collection and trade that could transfer huge amounts of wealth into the steppes and enrich thousands of pastoralists over many years.39

But none of these methods worked without some way of binding together regional nomadic armies into durable and disciplined coalitions. And this was the most difficult challenge for would-be mobilizers in the steppes: holding together military alliances that could mobilize from agrarian regions over many years, despite being formed from diverse, geographically scattered groups of pastoralists. Given the volatility of steppe politics, maintaining loyalty and discipline was an extraordinarily difficult juggling act that required a carefully calculated and ever-changing mixture of rewards and punishments. That required great political finesse from leaders because, in a world with few formalized institutions, alliances that depended almost entirely on personal relationships could snap in an instant over a casual insult or a single bad decision or military reverse.

What could hold such alliances together? First, flows of booty, skillfully distributed, could bind individuals, clans, and whole tribes into larger alliances. Knowing that their leader had the necessary vision and political skills made it worthwhile for regional chiefs to accept subordination to a supreme khan. Indeed, it often makes sense to think of such systems not as “states,” but rather as businesses, medieval versions of Walmart, perhaps, whose profits and costs were shared by leading participants.

… according to the Mongol tradition [the empire] was a joint property of the whole family of Chinggis Khan, among whom the Qa'an was only primus inter pares. The conquered lands were regarded as a common pool of wealth, that should benefit all the family members, and this principle was expressed in granting to individual princes local rights, mainly revenues from the conquered areas or lordship over a certain segment of the population.40

Most important of all in a world of personalistic politics were the skills of individual leaders and the cohesion and discipline of leadership groups. Building elite discipline began with family, clan, and lineage networks, the default social glue of most human societies without bureaucratic institutions. A skillful and charismatic leader could use such ties to build large, powerful, and disciplined mobilizational systems by the modular addition of clan to clan and tribe to tribe.

But ties of kinship depended on trust and were easily broken. So the most powerful mobilizational systems in Inner Eurasia braced ties of kinship with more impersonal ties of mutual advantage, service, and military discipline. Temujin was a master at reinforcing or replacing ties of kinship with more reliable ties of fealty and mutual advantage to build a loyal and disciplined following. By skillfully balancing rewards (derived from large flows of resources from agrarian regions or trade) and discipline (based on the leader's power to promote, demote, and even execute followers), Temujin's keshig, his group of immediate followers, set a benchmark for elite discipline that would shape politics in the region for many centuries.

The great North African Muslim scholar Ibn Khaldûn (1332–1406) used the Arabic term asabiyya to capture the importance of elite cohesion and discipline. In 1401, during the siege of Damascus, he explained to Timur (who already understood this perfectly well) that “[s]overeignty exists only because of group loyalty (“asabiyya”), and the greater the number in the group, the greater is the extent of sovereignty.”41 The extraordinarily high level of discipline within the Mongol elite would find an eerie echo seven centuries later in the astonishing elite discipline of the Stalinist nomenklatura.

Elite discipline is important in all mobilizational systems. But it was peculiarly important in Inner Eurasia, where potential targets were well defended, surpluses were smaller, resources and potential allies were dispersed, politics was volatile, and institutional structures were fragile. Here, mobilizing large flows of resources meant exerting exceptional pressure over large areas, and in mobilizational systems, as in steam engines, the amount of pressure that could be exerted depended on the strength and resilience of the container. Too much pressure, and a mobilizational system, like a boiler, could burst. But an elite riveted together by a leader with charisma, and the skill needed to balance rewards and punishment, could generate enormous pressure and mobilize vast resources even from bases in the relatively impoverished lands of Inner Eurasia.

THE SMYCHKA: YOKING TOGETHER STEPPE ARMIES AND AGRARIAN RESOURCES

A simple metaphor or model may help bring together these ideas on the distinctive challenges of mobilizing in the Inner Eurasian steppes. In the 1920s, Soviet leaders talked of building socialism by “yoking together” the proletariat and peasantry, just as peasant farmers yoked teams of oxen or horses behind a plow. They called this “yoking together” a smychka. (See Chapter 13.)

Pastoral nomadic mobilization systems in Inner Eurasia also depended on a sort of smychka that yoked together two large social beasts: armies from the steppes, and wealth generators from agrarian regions. As Anatoly Khazanov, Thomas Barfield, Nicola Di Cosmo, and others have shown, the most successful steppe rulers built large and disciplined armies that could mobilize large flows of resources from wealthy agrarian regions. Like the peasant's plow-team, the Inner Eurasian smychka yoked together social beasts that would otherwise have grazed separately. Indeed, this is why it makes sense to describe the large political systems created so many times in the steppes as “empires,” or polities that ruled over peoples with very different cultural, ecological, and historical traditions.

But to hold a smychka together, you needed a strong yoke and a skillful driver. If the first two components of the smychka were steppe armies and agrarian wealth, the third was elite discipline. Without the yoke and the whip, the two beasts headed off in different directions and plowing ceased. No steppe empire could survive long without a high level of elite discipline and cohesion. The peculiar importance of good leadership under the difficult mobilizational conditions that existed in Inner Eurasia helps explain a persistent bias towards autocratic rule in many regions of Inner Eurasia. (Figure 1.4.)

Figure 1.4 Diagrammatic representation of the smychka.

Because historians have normally focused on state formation in agrarian regions, the metaphor of a smychka may seem back-to-front. But thinking in this slightly counter-intuitive way can highlight some distinctive features of Inner Eurasia's political history. For example, the idea of the smychka emphasizes the geographical, cultural, ethnic, and political division between the armies that mobilized Inner Eurasian resources and the farmers, traders, and city-dwellers who produced most of these resources. Yoking these groups together was never easy, so another distinctive feature of the smychka is the sustained cultural tension between different regions. This is a feature that steppe empires share with modern empires in so far as both are large mobilizational systems in which outlying regions differ in their cultural and historical heritage from the mobilizational heartlands. No steppe empires managed to generate a sense of solidarity that could bridge such deep ecological, cultural, and ethnic chasms. And, as sociologists from the time of Durkheim have argued, building durable or stable polities from components that do not share basic religious, cultural, or political norms is extremely difficult. The failure of the traditional steppe smychka to build widely accepted forms of legitimacy was one of its main weaknesses, and we will see many examples of the political fissures this could cause.

Of course, the cultural divide was far from absolute, which points to another important feature of the smychka. Its two lead animals were forced into close contact and over time they adapted to each other's habits and ways of doing things. In addition to wealth, people, and resources, the smychka mobilized consumer goods, knowledge, technologies, and cultural goods, including religions. We will see that agrarian regions, such as Muscovy, learnt much about politics, mobilization, and warfare from steppeland overlords. But even more cultural and economic wealth flowed in the opposite direction.

As Juvaini wrote of the Mongols in the imperial period:

all the merchandise that is brought from the West is borne unto them, and that which is bound in the farthest East is untied in their houses; wallets and purses are filled from their treasuries, and their everyday garments are studded with jewels and embroidered with gold…42

The Mongol military machine mobilized the military skills of Chinese military engineers, including their use of gunpowder weapons, particularly bombs, often fired by trebuchets, and “fire-lances.” They may even have used the first true guns, which recent evidence suggests were invented in the Xia Xia state while Chinggis Khan was alive.43 The Mongol bureaucracy mobilized the bureaucratic skills of the Uighurs, and the fiscal skills of Muslim merchants. Religious traditions, too, circulated within pastoral nomadic empires, and were inspected carefully for their political and ideological value.

Over time, pastoral nomadic elites adopted many of the technologies, consumer goods, and cultural goods of the agrarian world, and gradually habits of consumption and even prayer began to transform the culture and lifeways of the steppes, and particularly the steppe elites. At least since the time of the Khazar Empire, late in the first millennium, some pastoral nomadic elites had converted to religions from the agrarian world. These cultural transfers suggest some of the ways in which steppe empires decayed. The traditions of the agrarian world had their greatest impact on pastoralist elites, and over time they could divide khans from the herders who made up their armies. Pastoralist leaders who became too used to the cities from which they drew most of their wealth, and to the silks, wines, and religious traditions of the agrarian world, could quickly lose their grip on steppeland armies, as the agrarian and steppeland drivers of the smychka began to pull in different directions.

Finally, the metaphor of a smychka highlights the importance of the constantly shifting balance of power between pastoral and agrarian regions. The smychka required military superiority, so it was difficult to operate in regions such as Central Asia, where pastoralist groups were divided and the balance of power between farmers and pastoralists was more even. Particularly in the more urbanized regions of Central Asia, the balance of power between agrarian and steppe regions was so stable for so long that the smychka’s two beasts constantly butted heads, creating a perpetual stasis. The most favorable configuration for a successful smychka was when steppe armies had a clear military superiority over nearby agrarian regions from which they mobilized.

THE FINAL YEARS OF THE MONGOL EMPIRE

The Mongol Empire was the most powerful mobilizational machine of this kind ever created in Inner Eurasia. But it, too, shows the brittleness typical of the smychka. The empire nearly fractured during the short reign of Guyug (r. 1246–1248). But it held together during the reign of Mongke (r. 1251–1259), who had inherited some of the political skills of his grandfather, Chinggis Khan.44 After his election in 1251, Mongke launched a brutal purge of the Chaghatayid and Ogodeid lines, descendants of Chinggis Khan's middle sons. As many as 300 Chinggisid nobles and commanders may have been tried and executed, after being hunted down by military search parties organized in huge military nooses as if for battue hunts.45

For a decade, Mongke balanced rewards and discipline skillfully to maintain elite discipline, and the empire continued to expand during two new campaigns of conquest that generated the vast flows of resources described by Juvaini. The first campaign, under Mongke's brother, Qubilai, invaded southern China. The second, under another brother, Hulegu (1217–1265), conquered Persia and parts of Mesopotamia. Both campaigns yielded huge rivers of booty that could be redistributed to regional elites. Government officials collected resources and booty at strategic urban centers, under the supervision of three secretariats, one in Beijing, one in Besh-Baligh, and one in Transoxiana.46 The western regions, ruled by Mongke's cousin, Batu, were less tightly integrated into the system. But even Batu, by now the senior Chinggisid, accepted Mongke's authority and participated in his military campaigns. In August 1253, Batu's officials told William of Rubruck that, “Baatu [Batu] has no power to do without Mangu Chan's [Mongke Khan's] consent. So you and your interpreter must go to Mangu Chan [Mongke Khan].”47 They were not making this up. Perhaps because he was aware that major sources of booty might be drying up, Mongke was meaner with the empire's wealth than his predecessors. So, when Batu requested 10,000 ingots of silver to buy pearls, Mongke sent him 1,000, as a loan against future grants, along with a lecture on thrift.48

In 1259 the Mongol Empire seemed more powerful than ever before. A year later, it did not exist. Mongke's sudden death in August 1259 illustrated the key role of leadership in the smychka, because immediately after his death the system sheared apart, splitting from top to bottom.

NOTES

REFERENCES

- Abu-Lughod, Janet L. Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250–1350. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Allsen, T. T. Commodity and Exchange in the Mongol Empire: A Cultural History of Islamic Textiles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Allsen, T. T. Mongol Imperialism: The Policies of the Grand Qan Mongke in China, Russia, and the Islamic Lands, 1251–1259. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Allsen, T. T. “Mongol Princes and their Merchant Partners.” Asia Major 3, No. 2 (1989): 83–126.

- Allsen, T. T. “Spiritual Geography and Political Legitimacy in the Eastern Steppe.” In Ideology and the Formation of Early States, ed. H. J. M. Claessen and J. G. Oosten, 116–135. Leiden: Brill, 1996.

- Andrade, Tonio. The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation and the Rise of the West in World History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Atwood, Christopher P. Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York: Facts on File, 2004.

- Barfield, Thomas J. The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China. Oxford: Blackwell, 1989.

- Biran, Michal. Chinggis Khan. Oxford: Oneworld, 2007.

- Biran, Michal. “The Mongol Empire and Inter-Civilizational Exchange.” In Cambridge World History, Vol. 5: Expanding Webs of Exchange and Conflict, 500CE–1500CE, ed. Benjamin Z. Kedar and Merry Wiesner-Hanks, 534–559. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Biran, Michal. Qaidu and the Rise of the Independent Mongol State in Central Asia. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press, 1997.

- Brooke, John L. Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Cook, Michael. “The Centrality of Islamic Civilization.” In Cambridge World History, Vol. 5: Expanding Webs of Exchange and Conflict, 500CE–1500CE, ed. Benjamin Z. Kedar and Merry Wiesner-Hanks, 385–414. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Dardess, John W. “From Mongol Empire to Yuan Dynasty: Changing Forms of Imperial Rule in Mongolia and Central Asia.” Monumenta Serica 30 (1972–1973): 117–165.

- De Rachewiltz, I. The Secret History of the Mongols: A Mongolian Epic Chronicle of the Thirteenth Century, 2 vols. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2004.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola. “State Formation and Periodization in Inner Asian History.” Journal of World History 10, No. 1 (Spring 1999): 1–40.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola, ed. Warfare in Inner Asian History: 500–1800. Leiden: Brill, 2002.

- Dunn, R. E. The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: A Muslim Traveller of the 14th Century. London: Croom Helm, 1986.

- Fletcher, J. F. “The Mongols: Ecological and Social Perspectives.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 46, No. 1 (1986): 11–50.

- Fuller, William C., Jr. Strategy and Power in Russia, 1600–1914. New York: The Free Press, 1992.

- Jackson, Peter. “From ulus to Khanate: The Making of the Mongol States c.1220–c.1290.” In The Mongol Empire and its Legacy, ed. R. Amitai-Preiss and D. O. Morgan, 12–38. Leiden: Brill, 1999.

- Juvaini. The History of the World-Conqueror by ‘Ala-al-Din Ara-Malik, trans. from the text of Mirza Muhammad Qazvini by John Andrew Boyle. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997.

- Khazanov, Anatoly M. “Pastoral Nomadic Migrations and Conquests.” In Cambridge World History, Vol. 5: Expanding Webs of Exchange and Conflict, 500CE–1500CE, ed. Benjamin Z. Kedar and Merry Wiesner-Hanks, 359–384. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Kiselev, S. V. and N. Ya. Merpert. “Iz istorii Kara-Koruma.” In Drevnemongol'skie Goroda, ed. Kiselev, 123–137. Moscow: Nauka, 1965.

- Levi, Scott C. and Ron Sela, eds. Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

- Liu, Xinru. “Regional Study: Exchanges within the Silk Roads World System.” In Cambridge World History, Vol. 4: A World with States, Empires and Networks 1200 BCE–900 CE, ed. Craig Benjamin, 457–479. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- McEvedy, C. and R. Jones. Atlas of World Population History. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

- Minert, L. K. “Drevneishie pamiatniki mongol'skogo monumental'nogo zodchestva.” In Drevnie Kul'tury Mongolii, ed. R. S. Vasil'evskii, 184–209. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1985.

- Minert, R. S. “Mongol'skoe gradostroitel'stvo XIII–XIV vekov.” In Tsentral'naia Aziia i Sosednie Territorii v Srednie Veka, ed. V. E. Larichev, 89–106. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1990.

- Olschki, L. Guillaume Boucher, a French Artist at the Court of the Khans. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1946.

- Pederson, Neil, Amy E. Hess, Nachin Baatarbileg, Kevin J. Anchukaitis, and Nicola Di Cosmo. “Pluvials, Droughts, the Mongol Empire, and Modern Mongolia.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, No. 12 (March 25, 2014): 4375–4379.

- Phillips, E. D. The Mongols. London: Thames and Hudson, 1969.

- Polo, Marco. The Travels of Marco Polo, trans. R. Latham. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1928.

- Rashid al-Din Tabib. Compendium of Chronicles: A History of the Mongols, 3 vols., trans. W. M. Thackston. Cambridge, MA: Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University, 1998–1999.

- Rogers, Clifford J. “Warfare.” In Cambridge World History, Vol. 5: Expanding Webs of Exchange and Conflict, 500CE–1500CE, ed. Benjamin Z. Kedar and Merry Wiesner-Hanks, 145–175. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Rossabi, Morris. Voyager from Xanadu: Rabban Sauma and the First Journey from China to the West, 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

- Rubruck, Friar William of. The Mission of Friar William of Rubruck: His Journey to the Court of the Great Khan Möngke, 1253–1255, trans. P. Jackson with D. Morgan. London: Hakluyt Society Series 2, 1990.

- Sherratt, Andrew. “Reviving the Grand Narrative: Archaeology and Long-Term Change.” Journal of European Archaeology 3, No. 1 (1995): 1–32.

- Sneath, David. “Mobility, Technology, and Decollectivization of Pastoralism in Mongolia.” In Mongolia in the Twentieth Century: Landlocked Cosmopolitan, ed. Stephen Kotkin and Bruce A. Elleman, 223–226. New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1999.

- Vladimirtsov, B. Y. Obshchestvennyi Stroi Mongolov: Mongol'skii Kochevoi Feodalizm. Leningrad: Academy of Sciences Press, 1934.

- Yingsheng, L. “Eastern Central Asia.” In History of Civilizations of Central Asia, 6 vols., 4: 574–584. Paris: UNESCO, 1992–2005.

- Yule, Sir Henry, trans. and ed. Cathay and the Way Thither, Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China. London: Hakluyt Society, vols. 33, 37, 38, and 41: 1913, 1924, 1925, 1926.