[3]

1350–1500: CENTRAL AND EASTERN INNER EURASIA

THE CRISIS OF THE MID-FOURTEENTH CENTURY AND THE FRAGMENTATION OF THE GOLDEN HORDE

If the thirteenth century was an era of expansion and increasing regional connections in much of Eurasia, the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries were dominated by decline and devolution. Climate change and the movement of diseases across the continent would shape the histories of many parts of Inner and Outer Eurasia.

CLIMATE CHANGE AND THE BLACK DEATH

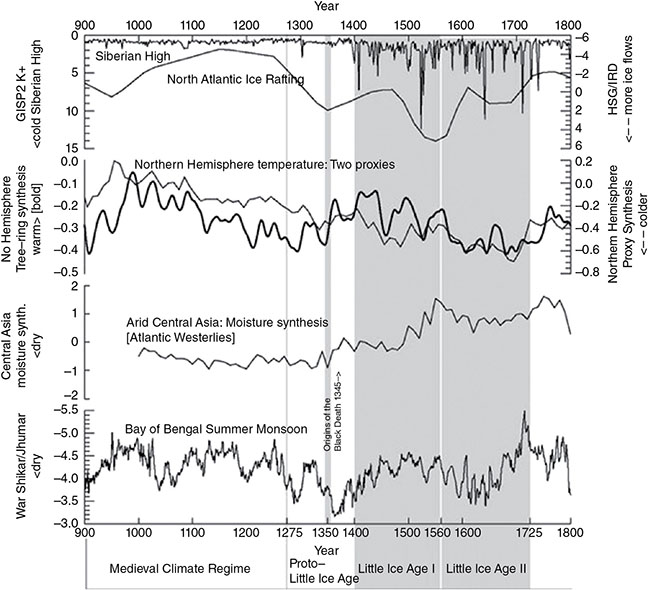

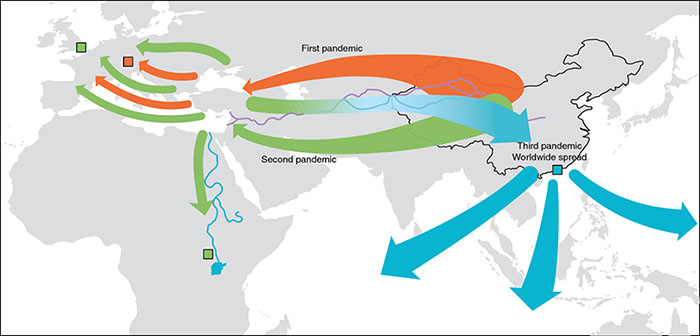

Beginning in the late twelfth century, climates in many parts of the world started to cool, beginning a slow descent into the Little Ice Age, whose coldest phase would be in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.1 In much of Inner Eurasia, though, climate change seems to have taken rather different forms, leading in some regions to warmer and wetter climates. Climate change was the first of two large trends that would shape many aspects of Eurasian history for several centuries. The second large trend was a series of plague epidemics that first struck in the middle of the fourteenth century. Climate change and plague may have been linked if, as John L. Brooke has suggested, increasing moisture in the steppelands multiplied the populations of fleas and rodents that carried the bubonic plague across Inner Eurasia from China to the Mediterranean world (Figure 3.1).2

Figure 3.1 Little Ice Age and the Black Death. Brooke, Climate Change, Figure III.10, 258. Reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press.

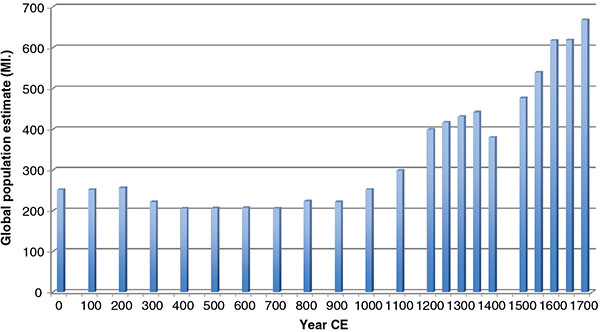

These large trends generated a demographic, economic, and political crisis that affected much of Eurasia in the mid-fourteenth century. As Figure 3.2 shows, available demographic evidence, though imprecise, suggests that this was the only century in the last millennium in which global populations actually declined, though there were several such periods in the previous millennium, some of them possibly linked also to the Black Death.3

Figure 3.2 Global population estimates to 1700 CE. Brooke, Climate Change, Table III.1a, 259. Reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press.

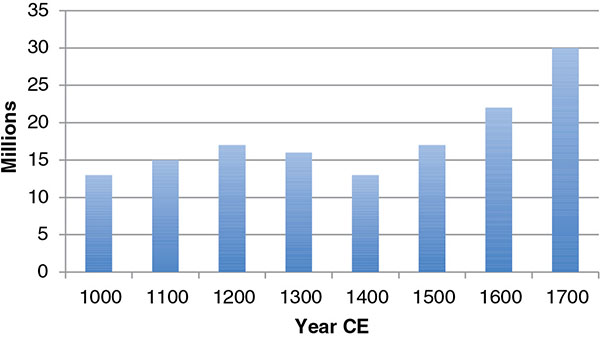

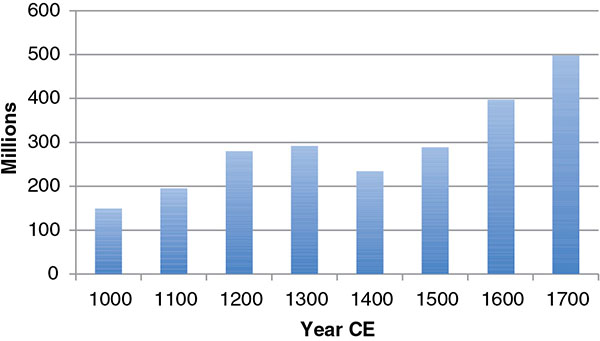

In Inner Eurasia, where surpluses were smaller and less certain than in Outer Eurasia, and climatic instability could quickly stir up widespread conflict, the impact of such crises was magnified, as the charts suggest. According to Biraben's figures (see Figures 3.3 and 3.4), the population of Inner Eurasia may have declined in both the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, while in Eurasia as a whole, the decline is most evident in the fourteenth century. The Eurasia-wide extent and scale of the fourteenth-century crisis can be explained, in part, by the increasing connectedness of the thirteenth-century “world system.” As Abu-Lughod put it, “just because the regions had become so interlinked, declines in one inevitably contributed to declines elsewhere, particularly in contiguous parts that formed ‘trading partnerships.’”4 In Plagues and Peoples, William McNeill explained how the expansion of exchange networks after 1000 CE guaranteed that the plague would reach regions whose populations lacked immunity to it, so that the plague took the horrifying form of what Alfred Crosby has called “virgin soil epidemics.” These are epidemics “in which the populations at risk have had no previous contact with the diseases that strike them and are therefore immunologically almost defenseless.”5 Recent scholarship has demonstrated the close link between large-scale plague epidemics and integrative pulses that link once separated regions, for this was not the first time that the bubonic plague (Yersinia pestis) had spread through Inner Eurasia.6 It had also spread in the sixth century CE during the so-called Justinian Plague, after which it recurred for two more centuries. As in the fourteenth century, the Justinian Plague probably originated among rodent populations in northern Xinjiang before spreading along migration and trade routes of the Silk Roads, along the southern borderlands of Inner Eurasia, to the Mediterranean and Europe (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.3 Biraben: populations of Inner Eurasia, 1000 to 1700 CE. Data from Biraben “Essai.”

Figure 3.4 Biraben: populations of Outer Eurasia, 1000 to 1700 CE. Data from Biraben “Essai.”

Figure 3.5 Possible routes for the spread of bubonic plague during three pandemics, in the 6th–8th, 14th–17th, and 19th–20th centuries. Wagner et al., “Yersinia pestis.” Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.

The “Black Death” struck first in the middle of the fourteenth century, and then recurred, with declining virulence, for several hundred years. The first wave may have killed 30–40 percent of the population in both urban and rural areas. The Black Death reached Khorezm in 1345, and Saray in 1346. When it reached Khan Ozbeg's lands in October and November of 1346, a contemporary reported that “the villages and towns were emptied of their inhabitants,” while 85,000 deaths were reported in the Crimea.7 The plague reached Caffa, and from there Italian merchants fleeing Janibeg's besieging armies may have carried it to Italy. In 1348, the plague spread to the Levant and northern Africa. In 1349 it reached Spain, northwestern Europe, and Britain, as well as the Baltic and Scandinavia. By this circular route it entered Rus’ from the north-west, through the Baltic, reaching Pskov and Novgorod in 1352 and other parts of Rus’ the next year. The fact that the Black Death did not reach Rus’ directly from Saray suggests that by this time exchanges between Russia and Europe through Novgorod were more vigorous than those between Russia and Saray.

In 1353, the plague killed Prince Simeon of Moscow, one of his brothers, and both of his sons, as well as the Orthodox Metropolitan Theognostus. Prince Simeon's will captures the apocalyptic horror felt by contemporaries. “And lo, I write this to you so that the memory of our parents and of us may not die, and so that the candle may not go out.”8 In central Russia, the plague may have killed a quarter of the population. After its first assault, the plague struck Saray and the Russian lands again in 1364, 1374, and 1396, and for the last time in 1425.9 But its impact diminished as populations acquired increasing immunity. Its periodic returns explain why populations did not reach their pre-plague levels again until 1500, 150 years after its first appearance in western Inner Eurasia.

THE FRAGMENTATION OF THE GOLDEN HORDE

The Black Death was particularly destabilizing in Inner Eurasia, with its smaller surpluses and cities, and more fragile polities. It certainly helped shatter the Golden Horde, the one Mongol successor state that survived into the mid-fourteenth century. But other factors were important, too. The Ottoman seizure of Gallipoli in 1354 throttled trade through the Bosporus, while the collapse of the Yuan dynasty in 1368 reduced trade along the Silk Roads, and declining silver production in Central Europe created a bullion shortage.10 Goods that had been carried through the southern borders of the Golden Horde after the collapse of the Il-Khanate in the 1330s began once more to flow south through Iran or northwards through Rus’.11 In the last two decades of the fourteenth century, Timur's devastating campaigns (see below) ruined many of the cities and trade centers of the Golden Horde, including its new capital, New Saray. By the early fifteenth century, the ancient trade in silks and spices through the Pontic steppes had declined as increasing amounts of Chinese goods were carried through the Indian Ocean. The extensive trade networks once managed from Saray fell under the control of regional powers, from Novgorod to Lithuania to Crimea, Kazan’, and Moscow.12

If these changes felled the Golden Horde, the Black Death finished it off. The bubonic plague flourished in armies on campaign, pruned ruling lineages, and ignited vicious succession struggles. In the late 1350s, Batu's lineage died out amidst brutal fratricidal conflicts. Khan Berdibeg (r. 1357–1359) succeeded to the khanate probably after murdering his father, Janibeg (r. 1342–1357), the builder of New Saray. Berdibeg was murdered by another brother, who was murdered in turn by another brother, Nawroz. Nawroz, the last of the Batuids, left no heir. Now each of the four leading noble families in the Golden Horde began to support rival claimants to the throne. In a fractal repeat of the breakup of the Mongol Empire, the Golden Horde split into regional uluses, each of which now had to build its own, regional smychka.13

After 1360, the Golden Horde fell apart during a twenty-year civil war that Russian sources call “The Great Troubles.” Khans succeeded each other with dizzying speed as regional leaders put up rival claimants. Rivals fought over four core territories: (1) Crimea and the Crimean steppe; (2) the steppes and cities of the north Caucasus; (3) the Volga delta region around Saray; and (4) the steppes of Kazakhstan and the cities of the Syr Darya and Khorezm. Each region had once been a princely ulus and each yoked together agrarian regions and commercial cities with pastoralist armies from the steppes. Eventually, (5) a fifth core region emerged near modern Kazan’, in what had once been Volga Bulgharia. In the fifteenth century, each of these regions would support mobilizational systems based on cut-down versions of the smychka.

The career of Emir Mamaq (d. 1381) illustrates the complexities of “The Great Troubles.”14 Mamaq had been Khan Berdibeg's leading emir (or beglerbegi), and also, in a common Mongol configuration, his son-in-law and marriage ally. Like Nogai in the previous century, he held lands in Crimea, the Crimean steppe, and the western borderlands. Not being a Chinggisid, Mamaq could only rule through, or with the support of, Chinggisid puppets. In 1361, he helped install Khan Abdullah in Saray. He then returned to Crimea to raise troops, leaving a power vacuum in Saray, during which three different khans were enthroned. For the next 20 years, there would be two major regional centers, one at Saray and the other with Mamaq in the Crimean steppes. This was a familiar division of power in the region, which had been prefigured a century earlier in the time of Nogai, and would recur again many times as rival systems appeared in the Volga delta and Crimea. Numismatic evidence suggests that the division between these two regions lay along the Volga itself, as coins minted under Mamaq are more common in cities west of the river, except for the brief periods when Mamaq and his puppet khans controlled Saray.15

As Saray's wealth and power ebbed, the borderlands fell away. Moldavia seceded in c.1359. In 1363, after the defeat of Jochid forces by the Lithuanian prince Ol'gerd at the battle of Blue Waters, the Podolian lands and most of the lands between the Dnieper and Dniester rivers stopped paying tribute. The rising Baltic power of Lithuania began to nibble away at the ancient heartlands of Kievan Rus’ along the Dnieper. Khorezm apparently became independent after 1361, for after that date its coins no longer carried the name of a Jochid khan. Astrakhan and Saraychik also rejected Saray's authority. At times Saray's rulers controlled little beyond Saray itself.16

With Batu's line extinguished, two other Jochid lineages challenged for power in the center of Inner Eurasia: the lineage of Batu's elder brother, Orda, and that of another brother, Shiban. In 1372, a descendant of Orda known as Urus Khan (d. 1377) moved west from his capital at Sygnak on the Syr Darya, conquered New Saray, and declared himself khan of the Golden Horde. (Urus's real name was Muhammad, but he was nicknamed Urus because of his resemblance to the Slavic Rus’.)17 Two of his former followers, another Jochid, Toqtamish, and a non-Chinggisid general known as Edigu, from the ulus of Shiban, sought the help of the rising Central Asian ruler Timur to overthrow Urus Khan. With Timur's support, Toqtamish (fl. 1375–1405) conquered Saray twice, in 1376 and again in 1380.18 Both Toqtamish and Edigu would have long careers with many odd twists and turns.

To the west, Mamaq controlled the traditional flows of tribute from Rus’. So important was the Rus’ tribute for Mamaq that when Grand Prince Dmitrii of Moscow (1359–1389) failed to deliver the full tribute because of chaos in the Horde and declining trade between Novgorod and the Baltic, Mamaq transferred the grand princely patent to the prince of Tver, only to return it after Muscovite armies defeated those of Tver. In 1380, Mamaq sent an army north to exact the full tribute from Moscow. At Kulikovo field, in September 1380, Prince Dmitrii of Moscow inflicted the first major defeat of Rus’ forces over those of the Golden Horde. The battle looms large in Russian historiography, but it was never just a conflict between a colony and its steppe overlords. Mamaq represented just part of the khanate, and he was allied with Lithuania, though no Lithuanian armies turned up to support him. Mamaq's troops were a motley collection of pastoral nomads, Genoese mercenaries from Crimea, and contingents from other Rus’ principalities.19 In 1381, Mamaq was defeated by Toqtamish on the Kalka river near Azov. He fled to Caffa, whose Genoese rulers murdered him.

Toqtamish now reunited the two main regions of the Golden Horde and in 1382 reasserted its authority in a brutal raid on Moscow. According to the Nikon chronicle:

Until then the city of Moscow had been large and wonderful to look at, crowded as she was with people, filled with wealth and glory … and now all at once all her beauty perished and her glory disappeared. Nothing could be seen but smoking ruins and bare earth and heaps of corpses.20

Awed by this reminder of the military power still wielded by the Jochid khans, several princes of Rus’ headed for Saray and submitted to Toqtamish. Khorezmian coins in his name show that he even reasserted Saray's authority over Khorezm.21

The revived Golden Horde lasted for just a decade. In 1390 and again in 1395, Timur crushed Toqtamish's armies and sacked Saray. After his second defeat, Toqtamish fled to Lithuania and was succeeded as khan by his former ally, Edigu (fl. 1395–1420). Edigu came from the Manghit tribes of the ulus of Shiban and would later be regarded as the founder of the Nogai (or “Manghit”) Horde. Like Mamaq, Edigu ruled the Golden Horde as beglerbegi through a series of Chinggisid puppets. The Golden Horde finally disintegrated after Edigu's death in 1420.

CENTRAL ASIA AND TIMUR

As the Golden Horde crumbled, new mobilizational systems emerged. The remarkable career of Emir Timur (c.1336–1405) illustrates a mobilizational possibility that would never be explored so thoroughly again: that of building a powerful smychka in the complex ecological patchwork of Transoxiana. Timur's career and those of his successors illustrate the difficulties of such a project, and help explain why, despite its wealth and sophistication, Central Asia provided an unstable foundation for a powerful mobilization system.

Timur was known as the “lame” (Aqsaq Timur) because an arrow wound to his right knee left him with a limp.22 Not being a Chinggisid, he never assumed the title of khan but ruled, like Mamaq and Edigu, as the emir and marriage partner of Chinggisid puppets. When Ibn Khaldûn met him outside Damascus in 1401, Timur explained, “I myself am only the representative of the sovereign of the throne. (As for the king himself) here he is,” and Timur pointed to a row of men standing behind him, one of whom was his Chinggisid stepson, but it turned out the boy had left the room.23

In the 1360s, Timur built up a powerful polity based on a smychka similar to that of Qaidu. It yoked the military power of Central Asian steppe armies (mostly from Transoxiana rather than Zungharia) to the commercial, financial, and technological resources of Transoxiana's cities. He extracted booty from a colossal looting zone reaching from Iraq and Anatolia to Russia and south to northern India. Timur also managed the unusual feat of yoking together the very different cultural and religious worlds of Central Asia's cities and steppes. He himself followed sharia law and supported Muslim institutions in the cities, but he accepted the more collectivist tribal rules of the steppes and many of his supporters followed traditional pastoralist religious traditions.24 However, unlike Chinggis Khan, Timur failed to ensure a smooth succession after his death. The Timurid polity survived his death in 1405, but would never again be as powerful as during his lifetime.

Timur was born in c.1336 in a pastoralist milieu in Kish (modern Shahrisabs), south of Samarkand. He belonged to a Turkicized tribe of Mongol pastoralists, the Barulas, who had adopted Islam and developed close ties with the region's cities. Some of their chiefs owned agricultural and urban land, though most Barulas lived as pastoral nomads.25 Like Chinggis Khan, Timur acquired his political and military skills in a world of vicious inter-tribal conflicts, complicated by the threat of invasion either from the khans of Moghulistan in the east, or from the Qara'unas in the south. The Qara'unas were descendants of Mongol armies settled in Afghanistan, who were ruled by Chagatay khans until the death of Tarmashirin in 1334.26 For these rival groups, Central Asia's cities were prizes to be fought over, but also sources of power because they were the hubs of networks of political influence, and could supply cash, luxury goods, and markets for booty, while their populations provided recruits and their workshops produced high-quality weaponry. The cities were also fortresses.27 In the late fifteenth-century memoirs of Babur, founder of the Mughal dynasty, we have a vivid description of warfare in this region, with its pitched battles and sieges, its betrayals and rapid reversals of fortune.28

Timur's rise to power, like Temujin's, shows the importance of building elite structures disciplined by mutual advantage rather than just by the looser ties of kinship. As Manz points out, the struggles of Timur's youth were not strictly between tribes but rather for control over tribes, their armies, and the cities they controlled.29 More reliable than the tribe was the uymaq, the personal household, retinue, or guard of a chief, the Central Asian equivalent of the Mongol keshig.

An uymaq was an elite military formation organized as a great household under the leadership of its chief. The chief was supported by his family and by other lesser chiefs and their followers whose support was won by delicate negotiations and/or by success in war. The uymaq chief used his military support to collect taxes from townsmen and peasants, and to establish, in effect, a local territorial government commonly based in a citadel or fortress.30

The uymaq that gathered around Timur would eventually form the core of a new and highly disciplined ruling elite. Like many young pastoralist leaders, Timur learned his craft leading livestock raids, and members of these raiding parties would dominate the retinue of 300 or so soldiers that formed his uymaq. Timur's retinue was as diverse as Chinggis Khan's. Manz has identified 18 close followers, some related by marriage, some from smaller tribal groups, some with no tribal connections, and some, perhaps, of slave origin.31

His loyal followers made Timur a force to be reckoned with. Like Chinggis Khan, he extended his power by judiciously supporting and then betraying the region's most powerful rulers. In 1360, he supported an invasion of Transoxiana by the Moghul ruler, Khan Tughlugh-Temur (r. 1347–1363). In return, Tughlugh-Temur made Timur chief of the Barulas tribe and the Kish region. Within a year, Timur had switched his allegiance to Husain, the leader of the Qara'unas, and then back again to Tughlugh-Temur. After switching sides once more, in 1364, Timur and Husain drove Tughlugh-Temur out of Transoxiana, and Husain was elected emir at a special quriltai. Six years later, Timur overthrew Husain and arranged his execution.

Timur was elected emir of Transoxiana at a quriltai in 1370. He distributed Husain's many wives, taking some himself (including a Chinggisid, Saray Malik Khanim, who became his favorite wife), and giving others to his close followers, to form new ties of kinship within the emerging ruling elite.32 In the next 15 years he placed his own followers at the head of most of the major tribal units and armies of the Chagatay ulus, including the Qara'unas. Like Chinggis Khan, a combination of toughness, skill, and luck had helped him build a new ruling class whose members owed him everything.

As the ruler of Transoxiana, Timur controlled a large, powerful, and disciplined army. At its core were contingents of pastoral nomads, whose families accompanied them on the longer campaigns.33 Its strike force consisted of heavy cavalry, commanded by close followers of Timur, who were supported by large land grants. The cities provided infantry levies. On some campaigns Timur's army included elephants and, probably for the first time in the region, artillery and handguns. Timur's hybrid army of pastoralists, infantry, and artillery was much more expensive than traditional steppe armies so, while it could mobilize resources, it also depended on a vast flow of resources to keep it in the field. This may help explain why Timur, unlike Chinggis Khan, failed to build a durable system of tribute-taking outside his homeland. Instead, he treated conquered regions beyond his Chagatay ulus as looting zones. Looting zones became and remained the main source of Timur's wealth.

From 1380, Timur campaigned almost continuously, generating huge flows of booty that fueled and sustained his empire. Between 1381 and 1386 his armies fought in Khorasan and northern Afghanistan. In 1386 he invaded Persia. In the same year he began a long northern campaign against his former ally, Toqtamish, ruler of the Golden Horde. In 1390, Timur's armies pursued Toqtamish to the Volga, where they defeated him near modern Samara, then captured and looted his capital, Saray. In 1392, Timur set off on a five-year campaign in Persia and northern Mesopotamia. In 1394, his armies attacked Toqtamish once more, then raided north almost as far as Moscow, before looting Saray again on their return in 1395. New Saray would never recover and trade routes shifted south to the benefit of Timur's own capital, Samarkand.34 In 1398 Timur invaded northern India and sacked Delhi, in a campaign that would provide the symbolic justification for his descendant Babur's conquest of India a century later. In 1399, Timur campaigned in Syria and Anatolia. In 1404, he launched an ambitious invasion of China. His armies set off early the next year but got no further than Otrar, where Timur died. His death ended all plans for invasion, a powerful reminder of the crucial role of individual leaders in pastoralist politics.

Cities and the people and wealth they contained were the main prize of most of these campaigns. Once a city had surrendered, Timur's armies would seal up all but one entrance to prevent unauthorized looting and stop inhabitants from fleeing with their property. Tax collectors and torturers moved through the conquered city, assessing its wealth, finding what was hidden, and extorting tributes. What they took was carefully registered before being divided between the commanders of Timur's army, and only when the leaders had their share were ordinary soldiers allowed to plunder. Where cities resisted or tried to outwit him, Timur put their inhabitants to the sword, erecting pyramids of their skulls as a warning to others. After the destruction of Isfahan in 1388, the historian Hafiz-i Abru claimed to have counted 28 pyramids, each with about 1,500 skulls.35

Ibn Khaldûn witnessed the fall of Damascus in February 1401. After the town fell,

[Timur] confiscated under torture hundredweights of money which he seized. … Then he gave permission for the plunder of the houses of the people of the city, and they were despoiled of all their furniture and goods. The furnishings and utensils of no value which remained were set on fire … [Then the army was allowed to plunder the city for three days.] When the soldiers had seized all the furniture and utensils left in the city, they drove out of it in fetters men, women, and children, except those under five years old and the feeble aged.36

Timur lavished great care on his own lands. In the Chagatay ulus, he supported agriculture and commerce and rebuilt major cities, adding mosques, palaces, and fortifications.37 With his son Shahrukh, he renovated irrigation systems in what may have been the last large-scale irrigation works undertaken before the Russian conquest in the nineteenth century.38 Though personally illiterate, Timur valued cultural booty. He spent huge amounts adorning and enriching his capital, Samarkand. He had a lifelong passion for architecture, which he indulged in the great cities of Central Asia, particularly Samarkand. He collected beautiful objects, such as porcelains. He was interested in philosophy and poetry and played a good game of chess, and his interest in scholarship and scientific matters seeded a cultural renaissance in Central Asia in the early fifteenth century.

A Spanish ambassador, Clavijo, visited Samarkand in 1404. In Timur's time, the city had huge suburbs in which there lived craftsmen transported from conquered regions.

From Damascus he brought weavers of silk, and men who made bows, glass and earthenware, so that, of those articles, Samarcand produces the best in the world. From Turkey, he brought archers, masons and silversmiths. He also brought men skilled in making engines of war. … There was so great a number of people brought to this city, from all parts, both men and women, that they are said to have amounted to one hundred and fifty thousand persons, of many nations.39

According to Clavijo, there were so many captives that many lived outside the city “under trees and in caves.” He reported that Samarkand's markets were abundant and contained many foreign goods.

Russia and Tartary send linen and skins; China sends silks, which are the best in the world (more especially the satins), and musk which is found in no other part of the world, rubies and diamonds, pearls and rhubarb, and many other things. … From India come spices, such as nutmegs, cloves, mace, cinnamon, ginger, and many others which do not reach Alexandria.40

Though sedentary and nomadic regions were integrated into Timur's empire, the symbolic divisions of the smychka were never blurred.Pastoralists, most of whom were Turkic, specialized in warfare, while officials from the sedentary population (mostly Persian) dominated civilian government and managed the mobilization of resources, often under the supervision of Turkic emirs. The two spheres of warfare and government remained distinct ethnically, culturally, functionally, and administratively.41

After Timur's death in 1405, there followed a 15-year civil war that ended with the victory of his fourth son, Shahrukh (r. 1405–1447). Timur's successors all succumbed to the lure of Central Asia's magnificent cities. Like all Timur's sons, Shahrukh had grown up in a more urbanized environment than his father. He shifted his capital south to Herat in Khorasan, and devoted far more attention than his father to cultural and religious concerns. He spent lavishly on the beautification of major towns, and encouraged painting and literature. Shahrukh's son, Baysonghur, who ruled in Astarabad, was a passionate bibliophile, while his other son, Ulugh-Beg, who ruled in Samarkand (r. 1411–1449), earned fame as an astronomer and scholar. He encouraged the study of science and mathematics, and his observatory in Samarkand made some of the most precise astronomical measurements of the age and produced a new star catalogue. Ghiyath al-Din Khwandamir, a fifteenth-century historian, wrote:

Mirza Ulughbeg … was unique among His Imperial Majesty Shahrukh's sons for his great learning and patronage and among all his peers for his justice and equity. He united the wisdom of Galen with the magnificence of Kay-Kaus, and in all the arts, especially in mathematics and astronomy, there was no one like him.42

Even more striking was the cultural flowering of the court of Sultan Husayn Bayqara (r. 1469–1506), another grandson of Timur, who ruled in Herat. During his rule, Herat enjoyed a renaissance of Persian and Chagatay Turkic literature and art; it was also home to the great poet, Mir Ali Shir Nava'i, who wrote in both Persian and Turkic.

Like the later khans of the Golden Horde and Central Asia, Timur's successors became so urbanized that they lost their grip on the military power of the steppes. Indeed, their failure to maintain control of the steppes, and the large flows of booty that steppe armies could mobilize, highlights the remarkable political and military achievement of Timur. On the other hand, it may be that the sort of campaigns Timur had led were simply unsustainable. Under his successors, conquest gave way to diplomacy, trade, and cultural exchanges. Efficient management of the region's irrigation systems sustained agriculture. The patronage of wealthy and well-educated rulers supported architecture, scholarship, and the arts, and the region's twin capitals, Samarkand and Herat, were regarded as among the Islamic world's most beautiful cities.43

But while the cities flourished, the armies languished, and the flows of booty they had generated dried up, weakening the bonds of patronage and personal loyalty that held rulers and the army within a single political force field. In the second half of the fifteenth century, Timurid rulers survived in Samarkand (until 1501) and Herat (until 1507) more through luck than skill. But their military and political power dwindled, and they became increasingly vulnerable to challenges from the steppes. Many of the city-states of Central Asia came under the sway of charismatic religious leaders, as rulers tried to achieve through religious cohesion what Timur had achieved through alliance building, warfare, and the redistribution of booty.

Sufis spread Islam among Turkic and Mongol tribes throughout the steppe regions of Central Asia, the Tarim basin, and modern Kazakhstan and Xinjiang. Some acquired great political influence through the organization of tariqas, or sufi schools or brotherhoods. The most powerful of the proselytizers came from the Naqshbandiyya tariqa, whose authority would eventually rival that of the region's emirs. The Naqshbandiyya order received its name from Baha al-Din Naqshband (1318–1389), a Sufi master and near contemporary of Timur from north-east of Bukhara, who encouraged his followers to participate in political and commercial life. Many sufi acquired great wealth, particularly in the form of charitable endowments or waqf, while some became marriage allies of regional leaders. As Millward writes:

Their claims of descent from the prophet Muhammad, chains of initiation, networks of lodges, close ties to merchants and rulers, tombs which served as pilgrimage sites and their often considerable wealth made the larger Sufi orders (tariqa) especially the Yasawiyya and Naqshbandiyya powerful institutions with growing religious and political influence in the Mongol imperial period and after.44

Particularly influential in the fifteenth century was the Naqshbandiyya Khwaja Ahrar (1404–1490). Originally a farmer and merchant, Khwaja Ahrar became an influential teacher, and an adviser to the Timurid rulers of Samarkand. He dominated the city's political life for over 30 years after 1457, ruling at first with the military support of the Uzbek khan Abul-Khayr, but then in the name of the relatively weak Timurid rulers, Abu-Sa'id (1451–1469) and his son Ahmad (1469–1494).45 As Shaikh ul-Islam, Ahrar became the region's most important theologian, and through Sufi networks his influence extended deep into Moghulistan.

Part of the appeal of such figures was that many of their practices made sense in a steppe world of shamanic religions. Characteristic is a story told of Khoja Ishaq Wali (d. 1599), who spread Islam in the Tarim basin, Zungharia, and Semirechie. On hearing that a Kyrgyz chief was seriously ill, and his followers were making offerings to “idols,” he dispatched one of his own followers, whose prayers caused the chief to sneeze, stand up, and profess his commitment to Allah and his one servant and prophet, Muhammad. The chief's Kyrgyz followers immediately converted, and the silver from one of the idols was donated to the Sufis.46 Sufi power arose, in part, from their ability to work within the very different worlds of urban and steppe Islam.

But despite their broad cultural appeal, the religious traditions of the Sufis lacked the capacity of the traditional smychka to mobilize military power, and never again would Central Asian rulers form a mobilizational system as powerful as that of Timur.

MOBILIZATION IN THE KAZAKH AND MONGOLIAN STEPPES

When the yoke that held the smychka together snapped, its two beasts lumbered off in different directions to graze, and the smychka stopped working. We can see the process with exceptional clarity in the fifteenth century as old yoking mechanisms broke down.

In the fifteenth century, two large confederations emerged in the steppes of Central Asia and Mongolia: the Kazakh and the Oirat. Both formed powerful regional mobilization systems capable of modest predation on neighboring regions, but neither created a durable smyckha. Their attempts to do so illustrate the difficulties of such a project, and the complexity of the maneuvers that political and military virtuosi such as Chinggis Khan and Timur had made seem simple.

THE KAZAKH AND UZBEK STEPPES

In the Kazakh steppes north of Transoxiana, two distinct pastoralist confederations emerged early in the fifteenth century: the Kazakh and the Uzbek. Both were ruled by Jochid lineages descended from Orda or Shiban. And both would play a significant political, economic, and eventually symbolic role in the region up to present times. The Kazakh and Uzbek eventually split along ecological lines: the Kazakh kept their base in the steppes where now they provide an ethnonym for modern Kazakhstan, while the Uzbek settled in the urbanized south of Transoxiana and provide an ethnonym for modern Uzbekistan.

Originally, the Kazakh steppes fell within the ulus of Jochi's eldest son, Orda, sometimes known as the “White Horde.” But they also included the ulus of Batu's brother, Shiban, in the “Uzbek” steppes, north of the Caspian Sea. The ethnonym “Uzbek” probably referred, originally, to people of the Golden Horde, or the people of Khan Ozbeg.47 Shiban's ulus is sometimes called the “Blue Horde.” Both uluses had access to the cities of the Syr Darya and Semirechie, and the Silk Road trade routes that passed through these lands, while Orda's ulus also bordered on Oirat Mongol lands in Zungharia. For pastoralists in the Kazakh steppe, the natural mobilizational strategy was to control or tax resources from Silk Road commerce and from the cities of the Syr Darya and Transoxiana. But there is evidence that, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, there may have been small towns and areas of farming not just along the Syr Darya, but even in northern Kazakhstan, so even in the deep steppe there were opportunities to mobilize resources on a small scale from towns and farming regions.48

As we have seen, leaders from both the uluses of Orda and Shiban had played an active role in the politics of the Golden Horde after the extinction of the Batuid lineage in 1359. Toqtamish, a descendant of Orda, ruled Saray from 1377 to 1395, before being driven out by Timur, while Edigu, a descendant of Shiban, became the last ruler of the Golden Horde. Edigu claimed both Jochid ancestry and descent from the first Islamic caliph, Abu-Bakr. In steppe lore he would become a legendary figure, particularly among the Nogai (Mangit).49

After Edigu's death in 1420, power fragmented in the Central Asian steppes before the eventual emergence of two new confederations, loosely descended from the uluses of Orda and Shiban. In 1429, in “Chimgi-Tura” (“Chingis town,” modern Tiumen’) in western Siberia, a 17-year-old Shibanid chief, Abul-Khayr, was elected khan of a federation of 24 tribes from the “Uzbek” or Shibanid steppes. He proved an able leader, and stories of his rise are full of tropes familiar from the history of Chinggis Khan. His success in politics and war earned him the support of many regional leaders. Having defeated and executed his rival, Mahmud Khan, on the Tobol river, he “collected from his foe boundless spoil, ranging from rosy-cheeked slaves, racers, pack camels and tents, to hauberks, various arms and coats of mail, all of which were piled up before the khan's very tent. The khan then deigned to bestow them on his amirlar and bahadurlar according to their rank and fame.”50 He raided Khorezm in 1431, gained the allegiance of tribes from the ulus of Orda, conquered several Syr Darya towns in 1446, and made Sygnak his capital.51 By 1450, his rule extended from the Urals to Lake Balkhash and the Irtysh river. After the death of Timur's son, Shahrukh, in 1451, he began to play a role in succession contests in Samarkand, and married a daughter of Ulugh-Beg. This would create ties with urban Transoxiana that proved important a generation later and may have launched the migrations that would bring large numbers of Uzbek south.52

Abul-Khayr's treatment of Urgench, which he captured in 1431, suggests a ruler who understood the workings of the smychka, and the importance of gaining support both in the steppes and the cities. According to a contemporary report, Abul-Khayr

ordered the opening of the treasury, whose contents former rulers had gathered with great labor and many cares, and ordered two eminent emirs to sit at the doors of the treasury, as all of the commanders, companions of the khan and simple soldiers entered in twos and took as much [money and valuables] as they could take away and left. All the soldiers, according to the khan's command, [entered the treasury] and each took as much as they could and left.

Having done this, however, Abul-Khayr organized assemblies of the city's scholars, clerics, and poets to seek their support.53

With a bit more skill or luck, Abul-Khayr might have absorbed the Timurid domains in Transoxiana and once again yoked together the very different resources of Central Asia's cities and steppelands. However, such prospects were ended in 1457 when Abul-Khayr's forces were defeated by an Oirat army from western Mongolia. Abul-Khayr's authority was undermined and his forces split. In 1458, two descendants of Urus Khan, Giray and Janibek, whose father Abul-Khayr had killed, led 200,000 of Abul-Khayr's people eastwards to the Chu river in the Semirechie region of Moghulistan, whose ruler, Esen-buka-khan (1429–1462), granted them pasturelands in one of the few regions of steppe that was underpopulated.54 The 1458 split would provide a foundation myth for the modern Kazakh and Uzbek nations. It may be that it divided Abul-Khayr's followers according to ancient divisions between the lineages of Orda and Shiban.

Abul-Khayr died in 1467, and Giray and Janibek assumed leadership over most of his followers. To those they now ruled, they provided both a new dynasty and a new ethnonym, that of “Kazakh,” a word that meant something close to “freebooter” and is related to the word “Cossack.”The Kazakh dynasty would endure for over 350 years.55 Under Giray's son, Buyunduk (ruled 1480–1511),56 the Kazakhs secured control of most of the Syr Darya region, making Yasi (later Turkestan) their capital. Buyunduk's successor, Kasim Khan (r. c.1509–1523), was a son of Janibek. During his reign, the Kazakhs formed a more or less stable khanate, with an urban base in the prosperous Syr Darya cities. Some considered Kasim Khan the most powerful ruler since Jochi, and the true founder of the Kazakh khanate. It was claimed he could field a million warriors. The Kazakh became a significant international power, and negotiated with Muscovy.57 By Kasim's death in 1523, the Kazakhs controlled lands reaching from the Ural river to Semirechie.

Meanwhile, with a small group of followers, Abul-Khayr's grandson, Muhammad Shibani (1451–1510), fled west to Astrakhan. Then he returned and, with the support of the Yasawiyya Sufi order, whose members provided him with a retinue of a few hundred soldiers, he headed for the religious center of Bukhara.58 Muhammad Shibani became a devout Muslim, eventually claiming the title of “Imam of the Age, the Caliph of the Merciful One,” a way of advertising his Sunni credentials to his Sufi supporters and also to the Shia ruler of Persia, Shah Isma'il.59 For several years, like his later rival, the Timurid Babur, he and his armies roamed Transoxiana, trying to build a stable mobilizational system. In 1500, Muhammad Shibani seized Bukhara. The next year, he besieged Samarkand and expelled Babur.

Babur described the siege of Samarkand in his memoirs, which give a vivid account of warfare in this region. During the siege, which lasted many months, there were constant attacks and counter-attacks. Babur describes one occasion when the besiegers faked an attack on one side of the town, while sending several hundred men to scale the walls from another side, using siege ladders wide enough for several men to climb side by side.

Some Uzbeks were on the ramparts, some were coming up, when these four men arrived at a run, dealt them blow upon blow, and, by energetic drubbing, forced them all down and put them to flight. … Another time Kasim Beg led his braves out through the Needle-makers’ Gate, pursued the Uzbeks as far as Khoja Kafsher, unhorsed some and returned with a few heads.60

Eventually, the besiegers began to attack each night, beating drums and shouting beneath one of the city gates. And the city began to run short of supplies. People began to eat dogs and asses, and Babur knew the end was near when some fled the city:

The soldiers and peasantry lost hope and, by ones and twos, began to let themselves down outside the walls and flee. … Trusted men of my close circle began to let themselves down from the ramparts and get away; begs of known name and old family servants were amongst them.

Eventually, Muhammad Shibani allowed Babur to leave on a journey into exile that would eventually take him to Delhi as founder of the Mughal dynasty.

In 1507 Muhammad Shibani conquered much of eastern Khorasan, finally ending Timurid power in the region. The Shibanid conquest of Transoxiana was buoyed by a huge influx of perhaps two or three hundred thousand migrants from the Uzbek steppes to the more settled regions of Transoxiana. This migration reduced the demographic pressure in the Kazakh steppes that had fueled tribal conflicts in the late fifteenth century.61 It also shifted the linguistic balance in Transoxiana from Persian towards Turkic languages.

In 1500, Muhammad Shibani signed a peace treaty with the Kazakh leader, Buyunduk. This partitioned Central Asia, more or less along ecological lines. Though it did not prevent bloody warfare along the Syr Darya in the next decade, the treaty did allow the Uzbek leaders to establish their power in Transoxiana, while the Kazakhs consolidated their grip on the Kazakh steppes. By 1500, there had emerged two Central Asian mobilizational systems, one based in the Kazakh steppes and along the Syr Darya, the other in Transoxiana. All the components of a new smychka were present, but no Timur appeared to yoke them together into a larger mobilizational system.

MONGOLIA

After the collapse of the Yuan dynasty in 1368, no Mongolian power structures survived above the level of regional tribal leaders. But Mongolia was no longer a colony of China, and Ming China, whose leaders came from the Chinese heartland, showed little interest in Mongolia. Within Mongolia, traditional power structures re-emerged and local leaders began, once again, to form regional systems of rule.

Two larger regional coalitions appeared in the early fifteenth century. They are known to historians as the Khalkha and the Oirat. The Khalkha emerged in eastern Mongolia and had Chinggisid leaders, while the Oirat (Kalmyk in Turkic) emerged in western Mongolia and had non-Chinggisid leaders. Conflicts between these groupings recapitulated the Han era rivalries between the Xiongnu and Yüeh-chih, and the sixth- and seventh-century divisions within the Türk Empire. The rivalry between Oirat and Khalkha would persist until its apocalyptic finale in the mid-eighteenth century, when the Khalkha lands became a Chinese colony again, and the Oirat were destroyed by Chinese and Khalkha armies.

The Oirat are first mentioned in the writings of Rashid al-Din as western rivals of Chinggis Khan.62 Because Qutuqa, an early thirteenth-century ancestor of the leading Oirat clans, had married daughters of Chinggis Khan and Jochi, the Oirat elites counted as quda, or marriage allies of the Chinggisids.63 But, like Timur, they could not legitimately claim the title of “khan.” Like all steppe confederations, the Oirat included many different tribes, traditions, and languages. Some, such as the Uighurs and Kereyit, were not strictly Mongol. Oirat lands included prosperous agricultural regions and rich pasturelands, and because they straddled the eastern Silk Roads the Oirat, like the Mongols and Türk before them, collaborated with Central Asian merchants to control and tax trade along the eastern Silk Roads. This explains why many Muslim names appear within the Oirat ruling elites, and why Oirat tribute missions to China were often led by Central Asian merchants. Their commercial interests also explain why the Oirat were so keen to open markets on the Chinese border.

In the early fifteenth century, under Toghoon (d. 1438) and his son Esen (r. 1438–1454), the Oirat established a short-lived hegemony over the whole of Mongolia. Toghoon defeated the Khalkha in 1434 and secured control of much of Qaidu's former territory of Zungharia, as well as the lands around Karakorum and north of the Chinese frontier.64 In 1438, the Ming agreed to open horse markets where the Oirat and their allies could send tribute missions and trade with Chinese merchants. Not surprisingly, given the fat profits to be made through trade and diplomacy, many Oirat and merchants were keen to join the missions, so they grew in size, and their demands became more insistent. According to the official history of the Ming:

Formerly, Oirad emissaries had never exceeded fifty persons; [later] in order to obtain ranks and bestowals from the Court [they] increased to more than two thousand people. The court issued several decrees ordering reductions, but each was ignored. Killing and looting occurred at the arrival and departure of each mission.65

In 1449, the Chinese refused to accept a “tribute” mission of 3,000 people. The Oirat leader, Esen, invaded China and captured the emperor, keeping him prisoner for a full year. In 1452/3 Esen defeated the eastern Mongolian khan, and proclaimed himself khan, the only non-Chinggisid ever to do so in Mongolia.66 This breach with Mongolian political etiquette offended many Mongol leaders, including some of his own commanders.67 But it seems that, unlike Temujin or Timur, he had also failed to build a sufficiently loyal and disciplined following. In 1454, he was murdered by chieftains disgruntled by his assumption of the title of khan and the miserly rewards he offered them. Nevertheless, Esen's victories had shifted the balance of military power along China's northern borders enough to persuade the Ming to start building a new and more powerful “Great Wall” along the southern edge of the Ordos.

With no obvious successor to Esen, the Oirat confederation collapsed. Though they had managed to assemble powerful armies and control significant flows of wealth for several decades, the Oirat had failed to build a durable smychka, or establish relations of equality with China. Geography undoubtedly complicated their task, for the western Mongolian homelands of the Oirat were far from any major agrarian power. This shielded them from attack, but limited the possibilities for mobilizing resources from sedentary regions.

NOTES

REFERENCES

- Abu-Lughod, Janet L. Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250–1350 New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Adshead, S. A. M. Central Asia in World History. London: Macmillan, 1993.

- Akhmedov, B. A. Gosudarstvo Kochevykyh Uzbekov. Moscow: Nauka, 1965.

- Alef, Gustave. “The Origins of Muscovite Autocracy: The Age of Ivan III.” Forschungen zur osteuropäischen Geschichte. Wiesbaden: Osteuropa-Institut, 1986.

- Atwood, Christopher P. Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York: Facts on File, 2004.

- Babur. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor, trans. Wheeler M. Thackston. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Biraben, J. R. “Essai sur l’évolution du nombre des hommes.” Population 34 (1979): 13–25; the crucial data from this is also available in Cambridge World History, Vol. 5: Expanding Webs of Exchange and Conflict, 500CE–1500CE, ed. Benjamin Z. Kedar and Merry Wiesner-Hanks, 19. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Brooke, John L. Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Clavijo, Ruy Gonzalez de. Narrative of the Embassy of Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, to the Court of Timour at Samarcand A.D. 1403–6, trans. Clements R. Markham. London: Hakluyt Society, 1859.

- Crosby, Alfred W. “Virgin Soil Epidemics as a Factor in the Aboriginal Depopulation in America.” William and Mary Quarterly (Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture) 33, No. 2 (1976): 289–299.

- Crummey, R. O. The Formation of Muscovy, 1304–1613. London and New York: Longmans, 1987.

- Dale, Stephen. Garden of the Eight Paradises, Babur and the Culture of Empire in Central Asia, Afghanistan and India (1483–1530). Leiden: Brill, 2004.

- Dale, Stephen. Indian Merchants and Eurasian Trade, 1600–1750. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Egorov, V. L. Istoricheskaya Geografiya Zolotoi Ordy v XIII–XIV vv. Moscow: Nauka, 1985.

- Fedorov-Davydov, G. A. Obshchestvennyi Stroi Zolotoi Ordy. Moscow: Moscow State University, 1973.

- Golden, P. B. An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1992.

- Golden, Peter B. Central Asia in World History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Halkovic, S. A. The Mongols of the West. Bloomington: Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, Indiana University, 1985.

- Hambly, Gavin. Zentralasien. Fischer Weltgeschichte, Vol. 16. Frankfurt: Fischer, 1966.

- Ibn Khaldûn. Ibn Khalduûn and Tamerlane: Their Historic Meeting in Damascus, 1401 A.D. (803 A.H.), ed. and trans. Walter J. Fischel. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1952.

- Jagchid, Sechin and Van Jay Symons. Peace, War, and Trade along the Great Wall. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989.

- Janabel, Jiger. The Rise of the Kazakh Nation in Central Eurasian and World History. Los Angeles: Asia Research Associates, 2009.

- Klyashtornyi, S. G. and T. I. Sultanov. Kazakhstan: Letopis’ Trekh Tysyacheletii. Alma-Ata: Rauan, 1992.

- Langer, Lawrence N. “The Black Death in Russia: Its Effects upon Urban Labor.” Russian History 2 (1975): 53–67.

- Lapidus, Ira M. A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Levi, Scott C. and Ron Sela, eds. Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

- Lukowski, J. and H. Zawadski. A Concise History of Poland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- McChesney, Robert D. Waqf in Central Asia: Four Hundred Years in the History of a Muslim Shrine. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

- McNeill, W. H. Plagues and Peoples. Oxford: Blackwell, 1977.

- Manz, Beatrice Forbes. The Rise and Rule of Tamerlane. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Martin, Janet. Medieval Russia, 980–1584, 2nd ed. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Millward, J. A. Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007.

- Olcott, Martha. The Kazakhs, 2nd ed. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1987.

- Parker, Geoffrey. Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

- Perdue, Peter C. China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2005.

- Pierce, Richard A. Russian Central Asia 1867–1914. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1960.

- Pokotilov, Dmitri. History of the Eastern Mongols during the Ming Dynasty from 1368–1634, trans. R. Loewenthal, addenda and corrigenda by W. Franke. Philadelphia:Porcupine Press, 1976.

- Roemer, H. R. “Timur in Iran.” In Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 6: The Timurid and Safavid Periods, ed. P. Jackson and L. Lockhart, 42–97. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Schamiloglu, Uli. “Mongol or Not? The Rise of an Islamic Turkic Culture in Transoxania.” Published as “Beautés du mélange.” In Samarcande, 1400–1500, La Cité-oasis de Tamerlan: Coeur d'un Empire et d'une Renaissance, trans. and ed. V. Fourniau, 191–203. Paris: Autrement, 1995.

- Schamiloglu, Uli. “The Golden Horde.” In The Turks, ed. Hasan Celâl Güzel, C. Cem Oğuz, and Osman Karatay, 6 vols., 2: 819–835. Ankara: Yeni Türkiye, 2002.

- Smith, Richard. “Trade and Commerce across Afro-Eurasia.” In Cambridge World History, Vol. 5: Expanding Webs of Exchange and Conflict, 500CE–1500CE, ed. Benjamin Z. Kedar and Merry Wiesner-Hanks, 233–256. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Soucek, Svat. A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Vernadsky, G. V. The Mongols and Russia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1953.

- Wagner, David M.et al. “Yersinia pestis and the Plague of Justinian 541–543 AD: A Genomic Analysis.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 14, No. 4 (April 2014): 312–326.

- Zlatkin, I. Ya. Istoriya Dzhungarskogo Khanstva. Moscow: Nauka, 1964.