[4]

1350–1500: WESTERN INNER EURASIA

PICKING THE BONES OF THE GOLDEN HORDE

West of the Urals, several different types of polity competed for control of the lands once ruled by the Golden Horde. (1) Fragments of the Golden Horde formed regional khanates, operating local versions of the smychka. (2) Two agrarian empires on the borders of Inner Eurasia, Lithuania/Poland and the Ottoman Empire, began to encroach on western Inner Eurasia. (3) Finally, Tver and Moscow, two vassal principalities in the forest lands of Rus’, emerged as possible successors to the Golden Horde.

PASTORALIST SUCCESSOR STATES

After the collapse of the Golden Horde, no pastoralist polity would ever again dominate the western regions of Inner Eurasia. In some ways this is surprising. After all, pastoralist khans inherited the geographical heartlands of the Golden Horde, as well as its cultural and political traditions.

There are two possible explanations. The first invokes contingency. No Timur or Chinggis Khan emerged with the luck, the skill, the ruthlessness, and the charisma needed to forge a ruling elite so disciplined that it could yoke together the region's steppes and settled regions. The second explanation invokes the momentum of long-term trends. The spread of farming from western Inner Eurasia – Inner Eurasia's long-delayed agricultural revolution – gave increasing demographic and economic heft to agrarian polities in the west. Slowly, the balance of power tipped against regional pastoralists in a prolonged seismic shift in power, wealth, and lifeways.

In the fifteenth century three new khanates emerged west of the Urals. The “Great Horde,” based on the Volga delta and the pasturelands of the north Caucasus, was the natural successor to the Golden Horde. However, Timur's ruinous invasions and the decline of trade through the Volga delta region impoverished the Horde and its leaders, forcing them to revert to crude booty raids on their neighbors. The power of Saray crumbled like that of Karakorum, and the Great Horde, though it survived for many decades, was finally destroyed in 1502 by the Crimean khanate. The Crimean khanate was created in 1449, from bases in Crimea and the Pontic steppes. It would survive under a single dynasty, the Girays, until 1783 and forge one of the most powerful polities in the region. Finally, the Kazan’ khanate, based in the lands of the Volga Bulghars, existed for a century, from 1445 to 1552, before it was conquered by Ivan IV, Tsar of Muscovy. Chinggisid khans ruled each of the khanates, and each constructed some form of smychka. Their armies came from the pasturelands along the Volga or north of the Caucasus and Crimea, but their ruling elites and officials generally lived in the region's trading cities, grew wealthy from commerce, and adopted Islam.1

The Kazan’ khanate was established by a Chinggisid, Ulugh-Muhammad (r. 1419–1445), a grandson of Toqtamish. Ulugh-Muhammad created the Kazan’ khanate in the final stages of a remarkable career during which he had sampled rule in each of the three new khanates. He briefly ruled the Great Horde before being driven out and fleeing to the west. In the 1420s, he allied with the Lithuanian ruler Vitautas (r. 1392–1430). In 1427, Vitautas helped him become khan of Crimea, but in 1437 he was driven from Crimea and headed north. He defeated a Muscovite army, captured Prince Vasilii II of Moscow, and charged a huge ransom for the prince's release. By 1445 he had taken up residence in Kazan’ where he founded a new khanate.2

Ulugh-Muhammad's lineage would rule Kazan’ until 1517. The Kazan’ khanate recruited its armies from nearby steppelands, and its leaders, like the Volga Bulghars, identified themselves both as pastoralists and as Muslims. But its pastures were more restricted than those north of Crimea, and so were the flows of commerce through its realms. Kazan’ could and did treat borderlands (including Rus’) as looting zones. But its rulers lived in the cities of Volga Bulgharia, above all in Kazan’ itself, and much of its material wealth came from taxes on trade between the lower Volga and the Baltic. With large farming populations, its economic base and social composition, apart from its Tatar elite, were similar to the rising power of Moscow, generating rivalries that echoed ancient conflicts between Volga Bulgharia and the principalities of Kievan Rus’. Yet Kazan’ had far fewer resources than the major cities of Rus’, and by the early sixteenth century Kazan’ already looked like a client state of Moscow.

The Crimean khanate was formed in the former ulus of Nogai and Mamaq by Hajji-Giray, a disgruntled Chinggisid prince from the Great Horde, who, like Ulugh-Muhammad, had fled into exile in Lithuania. The leading Crimean clans, the Shirins, Barins, Arghins, and Kipchaks, invited him to become their ruler when they, too, broke with the Great Horde. He became khan in 1449, made Bakhchesaray his capital, issued coins of his own bearing the figure of an owl, and established a dynasty that would rule for more than three centuries.3

The khanate's heartland in the Crimean peninsula was agrarian, urbanized, cosmopolitan, and highly commercialized. In addition to Tatars, its population included Greeks, Italians, Armenians, and many Turkic-speaking Jews, as well as an itinerant population of merchants from Russia, Central Asia, and the Mediterranean. Even the Crimean Tatars were largely sedentary. However, in the Pontic steppes to the north, Crimea's four major clans controlled large and powerful groups of pastoralists, many of them Nogai Tatars. There was a natural and ancient smychka between Pontic steppe armies and Crimea's trading cities. Herodotus had described similar relations almost 2,000 years earlier. Crimea's khans used their military power to tax trade routes running both east and west from Central Asia to the Mediterranean, and north and south from the Baltic and Rus’ to Azerbaijan and Persia. They also harvested slaves captured from Lithuania and the principalities of Rus’. The khanate's core population in Crimea lived from agriculture, livestock herding, grape-growing, and trade. Geography gave the Crimean peninsula many advantages in building a well-balanced smychka.

To the south, the main threat came from the rising Ottoman Empire, and at first Hajji-Giray sought defensive alliances with Lithuania and Muscovy. But in 1478, the logic of shared religion and the Ottoman expulsion of the Genoese after conquering Caffa and much of the Crimean coast (in 1475) forced Hajji-Giray's son, Mengli-Giray (r. 1478–1514), to accept Ottoman suzerainty. Having been imprisoned by the Ottomans, he had little choice. The khanate would remain an Ottoman protectorate, while preserving considerable independence, and in the sixteenth century its armies would rival those of Muscovy and Lithuania/Poland.

BORDERLAND EMPIRES: THE OTTOMAN AND LITHUANIAN EMPIRES

We will discuss the Ottoman and Lithuanian empires only in so far as their activities shaped Inner Eurasian history. But even a cursory examination of their role in the region can tell us much about the distinctive mobilizational challenges faced by Outer Eurasian empires that tried to expand into Inner Eurasia. Earlier Outer Eurasian empires, including Achaemenid Persia and the Han Empire, had dabbled in Inner Eurasian affairs, usually to defend themselves against pastoralist raiders. But despite their wealth and power, none succeeded in building durable Inner Eurasian empires. Why?

The problem was that it was extraordinarily difficult and expensive to use agrarian armies in the steppes, where there was little farming and few cities, and the benefits of invading the steppes rarely justified the massive cost. Armies had to bring most of their own food, fodder, fuel, and even water. Meanwhile, pastoral nomads were experts at harassing large, slow-moving infantry armies and their supply chains. Finally, there was little booty to be found in the steppes. As a result, Outer Eurasian polities rarely committed sufficient resources to the task of conquering and occupying Inner Eurasian lands.

The Osmanli or Ottoman Empire first took an interest in Inner Eurasia from the fifteenth century, as overlords of the Crimean khanate.4 The Ottoman Empire was founded at the end of the thirteenth century by a Muslim warrior prince called Osman (?–1324), from a base in western Anatolia. In 1326 Osman's successors captured Bursa and made it their capital. In 1354, they captured Gallipoli, on the European side of the Byzantine Empire. Under Murad I (ruled 1362–1389) they continued to expand in the Balkans, building the first slave-based Janissary army (“new army” or yeni çeri) in the 1360s. They used Janissaries to conquer Sofia in 1382 and then most of the Balkans, after defeating Serbia in 1389 at the battle of Kosovo. The Balkan region, while remaining culturally distinct from the Muslim Empire, would become one of the wealthiest and most populous provinces of the emerging empire, and in many ways its fiscal and geopolitical heartland.5

In 1402, after a devastating defeat at the hands of Timur, the Ottomans rebuilt their Janissary army. Like many earlier Muslim armies, it was formed from captives with no loyalties to anyone but the Ottoman state. The devşirme system had emerged in the 1380s to supply non-Muslim children, mostly from the Balkans, who were captured or taken as tribute to be trained as officials or soldiers. The Janissaries constituted one of Europe's first standing armies and one of the first to make extensive use of firearms. The Osmanlis were the first European state to form a permanent artillery unit; this certainly existed by 1400, when they used artillery against Constantinople. By the middle of the fifteenth century, they had also adopted from Hungarian models the idea of a wagenburg, or a linked chain of wagons armed with artillery to break cavalry charges.6

In 1453, Muhammad II (r. 1444–1446 and 1451–1481) conquered Constantinople, and his empire became the dominant power in the eastern Mediterranean. The conquest of Constantinople marked a political, cultural, and military revolution in the eastern Mediterranean. It drove European traders west into the Atlantic, where eventually they would find new routes to Asia and to the Americas. The Ottoman conquest of Constantinople also reoriented the politics of the Pontic steppes, as the Ottoman Empire began to dabble in Inner Eurasia in order to protect its interests in the Balkans. By the late fifteenth century, an Ottoman navy, built by Bayezid II (1481–1512), dominated the Black Sea. In 1475, the Ottomans conquered Crimea. They made the Crimean khans their suzerains, and took the major Black Sea ports from the Genoese and Venetians.

The Lithuanian Empire and its successor, the joint Lithuanian/Polish polity, formed by the Union of Kreva in 1385, would play a major role in the western borderlands of Inner Eurasia until the eighteenth century. While Lithuania counts as an Inner Eurasian polity, Poland counts as an Outer Eurasian polity. So the Union of Kreva created a “Commonwealth” that would be tugged in opposite directions by the different religious, fiscal, political, and military demands of Inner and Outer Eurasia.

The Lithuanian Empire had emerged in the power vacuum created in Inner Eurasia's western borderlands by the Mongol conquests. Soon after Batu conquered Rus’, a pagan chief, Mindaugas (Mendovg, r. c.1240–1263), conquered much of Lithuania from a base in the city of Vilnius.7 Under Mindaugas's successors, Lithuania defended itself against the Livonian order in modern Estonia, and began expanding into the soft western borderlands of the Golden Horde, in modern Belarus and Ukraine. Lithuanian rulers built forts to control the riverine trades from the Baltic to the Black Sea, and between Rus’ and western Europe. By 1300, Lithuania was a major eastern European power under a dynasty later known as the Gediminids after its best known ruler, Grand Prince Gediminas (Gedymin, r. 1316–1342). Gediminas was a contemporary of Khan Ozbeg of the Golden Horde.8 As the Golden Horde disintegrated in the mid-fourteenth century, Gedymin's son and successor, Algirdas (Olgerd, r. 1345–1377), declared that “All Rus’ must belong to the Lithuanians.”9 In 1362 Algirdas captured Kiev. In 1363, in alliance with Toqtamish, he defeated an army from the Golden Horde at the battle of Blue Waters. Lithuania now controlled most of modern Belarus and much of western Ukraine. Its power lapped the shores of the Black Sea and it was the largest polity in Europe.10

The challenge for Lithuania's rulers was to hold together an extraordinarily diverse polity. By the late fourteenth century, the largely pagan Lithuanians ruled a population of almost 2 million people, most of whom spoke East Slav languages and were Orthodox Christians.11 Lithuania's economy, like that of Rus’, was based on peasant farming of limited productivity, so that the region's elites sought wealth by taxing trade, or capturing and selling slaves, booty, and land. Lithuania was particularly keen to control trade along the Dnieper by allying with and eventually conquering Kiev, Galicia, and Volhynia, even as those principalities continued paying tributes to Saray.12 Through strategic marriage alliances, the Gediminids also built client relations with western principalities of Rus’ such as Smolensk and Pskov, and even, briefly, with Moscow.

The 1385 Union of Kreva transformed the politics and interests of this ramshackle empire by uniting Lithuania with Poland. The Lithuanian King Jagiello (r. 1377–1434) married the Polish Queen Jadwiga after converting to Catholicism in order to secure an ally against the Teutonic Knights. The union created a single Catholic dynasty ruling two formally separate kingdoms, with subjects whose diverse linguistic, cultural, economic, and religious traditions pulled them in opposite directions, westwards towards central Europe, or south and east towards Ukraine, the Black Sea, and the Golden Horde.13 Ironically, in 1384 Jagiello had nearly married a daughter of Grand Prince Dmitrii Donskoi of Moscow, a marriage that might have drawn Lithuania to the east, turning it into a major Inner Eurasian power and a possible successor to the Golden Horde. Jagiello's cousin and rival, Vitautas, ruled Lithuania as “dux,” under Jagiello, the “supremus dux,” but retained considerable autonomy. As the Golden Horde fell apart, Vitautas built a chain of forts between Kiev and the Black Sea that gave him control of the trade routes from the Black Sea through Kiev and eastern Europe.14 In 1399, however, his armies were checked at the Vorskla river by the armies of Edigu, the last ruler of the Golden Horde. Vitautas's defeat was caused in part by the desertion of his former ally and Edigu's rival, Toqtamish.

Further east, Vitautas gained partial suzerainty over the rising principality of Moscow, though Moscow remained a vassal state of the Jochid khanate. Prince Vasilii I of Moscow (r. 1389–1425) married Vitautas's daughter, and after becoming grand prince in 1389, he accepted his Lithuanian father-in-law as his suzerain until Vitautas's death 40 years later. Early in the fifteenth century, then, it was Lithuania that seemed to have replaced the Golden Horde as the imperial power in Rus’. Vitautas controlled Smolensk, enjoyed suzerainty over Moscow, and considerable influence over Vladimir, Tver’, Riazan’, and Novgorod, while his power also reached deep into the Tatar steppes.15

However, Lithuania's partial hegemony over Rus’ did not outlive Vitautas, who died in 1430. The Ottoman conquest of Constantinople created a new rival for control of the Pontic coastal polities of Wallachia and Moldavia, and in the 1480s Lithuania lost its outlets on the Black Sea. After 1475, when the Crimean khanate became a client of the Ottoman Empire and an ally of Moscow, there began a period of almost 50 years during which Crimean armies regularly attacked Lithuanian territory, capturing vast numbers of slaves. Crimean armies attacked Kiev in 1482, penetrated far into Poland in 1490, and attacked Vilnius in 1505.16 By the late fifteenth century, the ambitions of Lithuania/Poland's rulers in Inner Eurasia seemed to have been checked.

THE WEST: AGRARIAN SUCCESSOR STATES AND THE AGRARIAN SMYCHKA

The third group of possible successor states to the Golden Horde included some of the principalities of Rus’.17

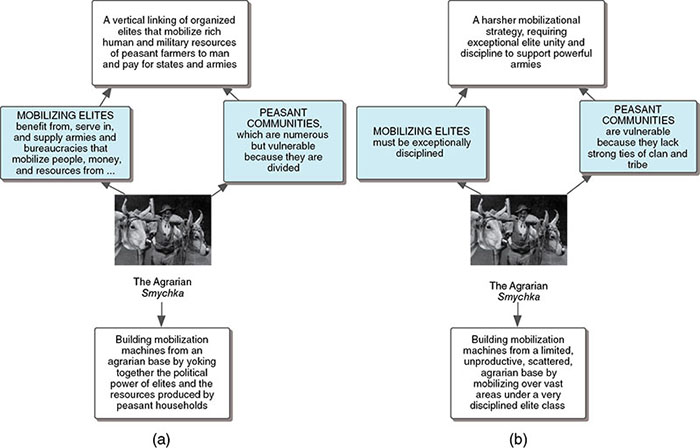

Unlike the borderland empires the Rus’ principalities could not avoid the mobilizational logic of Inner Eurasia. Here, as in parts of North Africa and Southwest Asia, polities based on agriculture emerged in regions long dominated by pastoral nomads. That changed many of the rules and strategies of state formation. So in this region it may prove illuminating to think of state formation using the slightly contrived metaphor of an agrarian smychka.

Here, too, state formation meant yoking together groups with different lifeways, cultures, and methods of mobilization. But while the nomadic smychka yoked groups divided by ecology and geography, the agrarian smychka yoked groups divided by class. It used the managerial and military skills of landed elites to mobilize the energy and resources of scattered populations of peasants. If in the nomadic smychka the role of leadership was to coordinate the actions of nomadic armies, in the agrarian smychka leaders had to coordinate the mobilizational activities of diverse, geographically scattered petty overlords in order to build armies. Local lords, in their turn, mobilized the labor, produce, timber, and other resources of local peasants. The agrarian smychka yoked together the productive energies of peasants and the mobilizational energy of local overlords to form, train, and supply armies that could protect the system from both external and internal enemies.

In Inner Eurasia, where resources were thin and scattered over vast areas, the mobilizational challenges of the agrarian smychka were particularly difficult. People, livestock, and resources had to be collected over vast areas. Yet the farming life, unlike the nomadic life, did not provide a natural training in warfare, so soldiers had to be specially trained. They also had to be supplied with food, equipment, horses, and weaponry. Furthermore, while in nomadic societies it was possible to mobilize most adult males, in agrarian regions it was possible to mobilize only a small proportion of the population, while the rest had to keep growing the crops that fed the army and paid for its weapons and equipment. This meant that, in order to form an army of comparative size to those of their pastoralist rivals, agrarian elites had to mobilize from much larger populations. So the agrarian smychka demanded more human, material, and financial resources and much more organization than the pastoralist smychka. It could succeed only if it enjoyed superiority in human, material, and organizational resources, and that superiority had to be very large indeed before it translated into a clear military advantage.

There is no need to overwork the metaphor of an agrarian smychka. Nevertheless, it may help bring out some distinctive mobilizational advantages and disadvantages of agrarian and pastoralist societies in Inner Eurasia. Agrarian societies suffered from significant military disadvantages, but they also enjoyed some important advantages, and these would slowly increase over many centuries.

First, clan and tribal structures were much weaker in agrarian societies, and created fewer barriers to centralized power. Ties between villages, unlike ties between pastoralist camping groups or clans, were extremely weak, so rulers and landed elites could usually control and tax villages one by one. As Marx famously argued in The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, peasants find it hard to defend themselves because they lack a sense of clan or class solidarity.

… the great mass of the French nation is formed by simple addition of homologous magnitudes, much as potatoes in a sack form a sackful of potatoes. In so far as millions of families live under economic conditions of existence that divide their mode of life, their interests and their culture from those of the other classes … they form a class. In so far as there is merely a local interconnection among these small peasants … they do not form a class. They are consequently incapable of enforcing their class interest in their own name … They cannot represent themselves, they must be represented.18

In Inner Eurasia, remoteness and isolation magnified these perennial weaknesses of peasant villages, and enhanced the power of the elites that “represented” them.

In Inner Eurasia, agrarian societies also enjoyed better prospects for growth than pastoralist societies. While pastoral nomadism had probably reached a peak of productivity as early as the first millennium BCE, agriculture was new in much of Inner Eurasia, and had room to expand. In any case, farming depends on plants more than livestock, so it mobilizes from lower on the food chain than pastoralism. That is why agriculture can generate more calories and support larger and more concentrated populations than pastoral nomadism. Over time these advantages accumulated, giving Inner Eurasia's agrarian regions more and more human and material resources until, eventually, the balance of power tipped decisively, and agrarian societies began to smother their nomadic rivals.

Meanwhile, as long as the balance of power in Inner Eurasia still favored pastoral nomads, agrarian polities had much to learn from the traditional smychka, and the many different ways it managed warfare, commerce, and the distinctive challenges of mobilization in Inner Eurasia (Figure 4.1a,b).19

4.1a,b

4.1a,bFigure 4.1a,b Two forms of the agrarian smychka.

RUS’ AND THE GOLDEN HORDE: 1237–1380

Before Batu's invasion, the principalities of Kievan Rus’ were already using simple forms of the agrarian smychka to mobilize armies that could protect them against the loosely organized pastoral nomadic groups in the Pontic steppes. But Batu's armies posed entirely new military challenges. They were better led, much larger, much better disciplined, and more ruthless than the steppeland societies familiar to the princes of Rus’. The Mongol invasion raised the bar for successful mobilization throughout Inner Eurasia, and leaders of Rus’ had to learn from it fast if they were to survive. It exposed the fundamental political, organizational, economic, and military weaknesses of the Rus’ principalities.

The first weakness was political. Rus’ was divided. Though formally subject to the grand princes of Vladimir, by the early thirteenth century the principalities of Rus’ were in practice independent, and each mobilized its own resources and armies. The Orthodox Church created a loose sense of religious identity, even if the real religion of most peasants had more to do with shamanic or magical traditions than with Christian theology. But a shared commitment to Orthodox Christianity was not enough to prevent endemic warfare between principalities over territory and booty. When Batu's armies invaded in 1237, they were able to pick off the capital cities of the major principalities one by one.

The second weakness was administrative. The princes of Rus’ had remarkably little power. Even in the fourteenth century, “Other than the swords of his retinue, a prince had only the aura of his office to make men do his will.”20 Princely armies of the Mongol era may even have been smaller than those of the Kievan era, just as princely households were probably poorer.21

The third weakness was economic. The armies of Rus’ were small because surpluses were small. Climates were harsh. On average only 140 days a year were frost free.22 Most soils were acidic, forest podzols, leached of nutrients and with low fertility. To farm, peasants had to clear the land, often using techniques akin to modern “slash-and-burn” farming. Then they plowed the cleared land using light, two-tined plows (the sokha), often moving around stumps rather than removing them. The primary crops had to be hardy. Rye, oats, and barley worked, while hay was cut to feed livestock. The fertility of the ash-covered soil would decline within a few years, after which new clearings would be made, and the older clearings would be left fallow for several decades. During the fifteenth century, more intensive, three-field systems began to appear, particularly where slash-and-burn farmers met up with each other (“where axe met axe” in the traditional phrase). Under the three-field system, one field would be left fallow each year, while one would be planted in spring with autumn crops and a third would be planted in the fall with crops that would be harvested the next summer. For such systems, heavier, usually horse-drawn plows were necessary, and livestock was crucial both for haulage and to provide manure. But to feed livestock farmers had to set aside special hayfields that, like fallow fields, could no longer feed humans. Even these more intensive systems yielded small and unreliable surpluses. Rarely did harvests amount to more than three times what was sown, so that even a small reduction in the harvest could mean famine.

With low and precarious yields, and small communities scattered over huge areas, mobilizing agrarian surpluses was extremely difficult. The existence of large, underpopulated regions on the northern, eastern, and southern borders of Rus’ added to the difficulty because, if pressed too hard, peasants could flee oppressive overlords. These difficulties explain why governments were so keen to mobilize non-agricultural resources, including forest products such as fish, berries, furs, timber, and honey, or livestock products from regions bordering the steppes. These goods could then be sent down the Volga or through the Pontic steppes to markets on the Black Sea, or westwards through the Baltic to the cities of Europe. All the towns of Rus’ levied taxes on commerce, while nobles, princes, and (later) monasteries taxed peasants and towns.

The trade in furs was particularly important; indeed, furs were so abundant and generated such huge revenues that, like oil today, they created a sort of “resource dependency.”23 (By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the trade in furs may have accounted for 10 to 25 percent of government revenue; a similar magnitude to the 25 percent yielded by oil and gas in 2005–2010.)24 Furs could also be used as the Chinese government used silks, as gifts to foreign envoys, or as an alternative to cash payments. The best furs, those with the thickest pelts, could be found only in the far north, and since at least the eleventh century, merchants and boyars of Novgorod had traveled up the Sukhona, Vychegda, and Pechora rivers to the lands of the Finnic-speaking Chud and Permians to extract high-quality furs by force or trade or tribute (iasak). Because indigenous communities saw little commercial value in them, furs offered immense possibilities for arbitrage as long as natives could be made to surrender them as tribute or persuaded to trade them for iron or trinkets or alcohol or tobacco or firearms. Revenues from the fur trade were shared between merchants and princes and their Mongol overlords. Growing demand for furs in Europe and the Muslim world drove colonization, as nearby regions were overhunted and new areas were opened up for exploitation. Eventually, increasing demand would drive Russian traders and their military escorts eastwards through Russia and into Siberia, just as it would eventually drive European traders westwards through North America.

The fourth weakness of the Rus’ principalities was military. Situated between agrarian regions and steppes, they faced two very different types of enemies and needed two very different types of armies, or armies that could do very different jobs. Cavalry worked on both fronts, but had to be used in different ways in the steppes or urban sieges. Before the middle of the fourteenth century, the princes of Rus’ mobilized armies in the simplest possible way, relying on informal ties of kinship and patronage. They assembled their own retinues, consisting of armed servitors and slaves from their own households and estates. Then they summoned their boyars and other members of the princely family to assemble with their retinues and meet at a particular time and place.25 In a crisis they could levy urban militias, but few towndwellers had military training and few towns could spare many recruits. So town militias were mostly used to move and transport fodder, supplies, and equipment. In the mid-thirteenth century, the most important units in a princely army were often units of Tatar troops supplied by their Tatar overlords or hired as mercenaries. No wonder princely armies were small. In the early Mongol period they rarely included more than a few hundred men. If joined by allies, and perhaps by pastoralist contingents and militias from the towns, they might amount to a few thousand men.

Rus’ armies were also undisciplined and untrained. There was no certainty that troops would show up, or, if they did, that they would fight on the right side. It was almost impossible to coordinate their movements on the battlefield, or to maintain discipline, particularly if there was a chance for looting, as booty or the capture of enemy troops for ransom provided one of the few rewards of soldiering. The one modest advantage enjoyed by Rus’ armies was long experience of fighting each other and pastoral nomads. Most princely armies were dominated by cavalry, and had some experience of the wars of speed, mobility, and deceit typical in the steppes. Inter-princely wars, like most wars in medieval Europe, were dominated by sieges, because cities warehoused wealth, and controlled the resources of surrounding lands.26 Pitched battles were unusual. They mostly occurred when one side tried to relieve a besieged city. When battles did occur, they were usually chaotic and small-scale affairs. Princes and commanders were reluctant to waste armies raised at great cost and effort, and usually retreated when faced with clearly superior forces.

These weaknesses explain why the princes of Rus’ had no choice about submitting and collaborating after Batu's invasion in 1237. Those princes that submitted could secure a iarlik or seal of princely office granted by the khans. They could also expect some Mongol military protection. But the khans were demanding overlords. Princes had to collect and hand over large amounts in tribute, and to take part in punitive raids on other principalities. Alexander Nevskii, who became prince of Novgorod just 15 years after Batu's invasion, received the title of Grand Prince of Vladimir (from 1252–1263) in return for a pledge of loyalty and help with Mongke's census of the Russian lands. In Novgorod, he used his own troops to protect Mongol census takers, knowing that resistance would provoke devastating retaliation. At the cost of humiliating symbolic concessions (the humiliation was real enough, and is reflected in chronicle accounts), Alexander Nevskii retained some independence in northeastern Rus’, and avoided ruinous punitive raids.27

Forests provided some protection because they reduced the mobility of nomadic armies, so, while steppe armies could launch devastating raids, only small contingents could stay in the north for longer periods. Soon, the khans of the Golden Horde discovered it was easier to control Rus’ indirectly through its princes. Indirect rule allowed Russian princes to build and maintain modest mobilizational machines that could raise the tributes and troops required by the Golden Horde. The Mongols also found it easier to manage Rus’ through a single grand prince, and this strategy would enhance the power and authority of the most powerful principalities, creating a fiercely competitive arena in which there could only be one final winner.

THE RISE OF MOSCOW: 1240–1400

Princes ruled from their capital cities. But with tiny agrarian surpluses, towns and cities were small. In thirteenth-century Rus’ no more than 30 towns had more than a few thousand inhabitants. The Mongol invasion ruined Kiev and Vladimir, the seats of the Kievan grand princes. By the end of the thirteenth century, other cities, such as Moscow and Tver’, were richer, more populous, and more powerful. Moscow and Tver’ also enjoyed strategic positions on the river systems that controlled the trade routes from Central Asia to the Baltic and Europe, and control of these routes was crucial because trade paid for much of the tribute demanded by Saray.

In the late thirteenth century, Novgorod and Pskov were the largest and wealthiest of the Rus’ cities. Far from the steppes, they had been spared during the wars of conquest. Novgorod had just over 20,000 inhabitants.28 It had grown wealthy by trading the furs and other resources of the far north through the Baltic to Europe, or through Rus’, the Volga river, and the Black Sea to the Mediterranean and Central Asia. But, though wealthy, Novgorod was militarily weak. Agricultural productivity was low, and its vast hinterlands underpopulated. Its oligarchic, merchant-dominated assemblies, or veche, elected and controlled their princes, who were usually too weak to raise large armies. So other, more powerful principalities, such as Rostov-Suzdal’, began to siphon resources from Novgorod's northern empire. In the western parts of Rus’, cities such as Smolensk or Kiev were weakened by their proximity to the rising power of Lithuania, while cities such as Riazan’, on the borders between the forest and the steppe, were vulnerable to steppe raids.

By the reign of Khan Ozbeg, early in the fourteenth century, Tver’ and Moscow had emerged as the most powerful principalities of Rus’. Neither was large. Moscow controlled about 20,000 sq. kilometers and had a total population of just a few hundred thousand people.29 However, both principalities combined modest agrarian wealth with strategic positions on the commercial waterways linking the Baltic to Central Asia and the eastern Mediterranean. And both were far enough from Lithuania and the Horde to enjoy some protection.

Saray's rulers took lineage seriously and usually respected local rules of succession. So, for the most part, they had supported the grand princes of Vladimir since the time of Alexander Nevskii. In 1304, Saray granted the iarlik as grand prince to the legitimate heir, Prince Mikhail Yaroslavich of Tver’, the son of Alexander Nevskii's brother and successor, Yaroslav. This was a golden opportunity for Tver’. But Mikhail missed his chance. His rival, Yurii Daniilovich, prince of Moscow (the elder son of Alexander Nevskii's son, Daniil), courted Saray more assiduously, ingratiating himself with Khan Ozbeg by demonstrating his control over the rich flow of goods through Novgorod, which supplied most of the silver for the vykhod or tribute. In 1316 Ozbeg transferred the title of grand prince to Yurii, despite his lack of legitimate claims to the title.30 Yurii returned from Saray with a royal bride (the khan's sister), and a contingent of Tatar troops. Next year, Prince Mikhail of Tver’ defeated Yurii's forces and their Tatar allies, and captured both Ozbeg's sister and his Tatar general, Kavgadii. The khan's sister would die in captivity. Mikhail and Yurii were summoned to the Horde, and in 1319 Khan Ozbeg had Mikhail executed. In the next four years, another four Jochid armies were sent to Rus’ to uphold the khan's authority and that of his new client, the prince of Moscow. The resistance suggests how reluctant most princes were to accept the princes of Moscow as legitimate grand princes.31

In 1322, Ozbeg returned the title of grand prince to the prince of Tver’, Mikhail's son, Dmitrii. But again, Tver’ missed its chance. In 1327, its citizens rebelled against an oppressive Mongol official, Schelkan. Ivan Daniilovich (r. 1327–1340), the new prince of Moscow since the death of his brother Yurii in 1327, joined a Mongol army in attacking Tver’. Tver’ was sacked, many of its citizens killed or enslaved, and its new prince, Alexander, fled to Lithuania.32 Prince Ivan Daniilovich of Moscow was made grand prince in 1331, and over the next few decades the title began to seem part of the natural heritage of Moscow.

These two episodes cannot convey the complexities of the long contest for hegemony between Moscow and Tver’, but they suggest some of the factors that determined its outcome. Crucial were the political skills of Ivan Daniilovich himself. He worked hard to cultivate support within the Golden Horde, spending many years in Saray, ingratiating himself with Khan Ozbeg and his advisers. The Soviet historian Nasonov calculated that he spent more than half of his reign in Saray or en route to the capital.33 But he also proved a competent gatherer of the Mongol tribute; hence, perhaps, his nickname of “Kalita” or “moneybags.” His mobilizational skills contributed to the growing prosperity of Moscow itself because, as grand prince, he made other princes hand over their shares of the vykhod to him before passing them on to Saray. That let him reduce the relative burden on his own principality. By the death of Prince Dmitrii Donskoi in 1389, just half a century after Ivan Kalita's accession, Moscow and its immediate surroundings contributed hardly anything to the tribute payments.34

With competent princes, Moscow's advantages multiplied. Prince Ivan used his growing wealth and influence to forge marriage alliances that bound other principalities such as Beloozero and Iaroslavl’ closer to Moscow. These alliances helped him muscle in on new sources of revenue, including the rich trade networks of Novgorod. As early as 1333 marriage alliances gave him control over Vychegda and Pechora, northern lands rich in furs that could be traded on to Saray and the Black Sea, or used as gifts or bribes or in diplomatic negotiations.35 Ivan also gained the support of the Orthodox Church. In the 1320s, Metropolitan Peter (1309–1326) moved to Moscow. He had supported Moscow in its conflicts with Tver’, and after his death in 1326 and canonization as a saint, his Moscow tomb became a shrine. Ivan persuaded Peter's successor, Theognostos (1328–1353), to settle in Moscow too, and during his long reign as metropolitan, Moscow became the permanent headquarters of the Russian Orthodox Church.36

Spared from Mongol raids for some 30 years under Ivan and his successors, Moscow grew wealthy and attracted increasing numbers of merchants, artisans, and impoverished princes. Moscow also shared in an economic and commercial boom that benefited much of northern Rus’ in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. Economic growth is apparent in urban construction. In 1367, Moscow built new stone walls that protected it from sieges. In Rus’ as a whole, perhaps 150 new monasteries were built in the century after 1350, often in remote areas, many inspired by the founding of the Holy Trinity Monastery by St. Sergius of Radonezh (c.1314–1392).37 The historian Kliuchevskii described this as “monastic colonization.”38

Moscow's leaders also managed to build an exceptionally united and disciplined elite group. In Rus’, as in the steppes, elite discipline was vital because human, material, and commercial resources were so thinly scattered that significant wealth could be controlled only by elite groups capable of coordinated mobilization over large areas. This was not a task for independent feudal lords, but demanded the synchronized action of many local lords. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Muscovy's boyar elite developed an exceptionally unified political culture. No other class or organization showed such unity, neither the church, nor the townspeople, nor the merchantry. Nancy Kollmann writes:

The boyars and grand princes depended upon their collective strength during the incessant warfare of the fourteenth century to maintain and increase their resources. Excessive internecine conflict (exemplified by the fifteenth-century dynastic war) threatened the elite's power and consequently their livelihood. The boyars’ military might also acted to restrain violence and to promote the grand prince's respect, for the boyars were armed and dangerous. In the fourteenth century their retinues formed the bulk of the sovereign's armies. In the very real leverage they possessed with regard to the sovereign might be found a source of the respect, personal association, and self-limiting constraints that are part of the political system we are examining.39

Why and how such a disciplined elite culture emerged in the principality of Moscow remains somewhat mysterious. Moscow's nobles may have modeled their behavior on the autocratic political culture of the Golden Horde, which they came to know more intimately than the leaders of any other principality. But Moscow's growing wealth and security surely played a role, because they made its prince an attractive patron to nobles from other principalities, even from Lithuania and the Golden Horde. Moscow's princely family also enjoyed a run of demographic good fortune. The ancient tradition of dividing a prince's inheritance between all living heirs could rapidly destroy even the wealthiest lineages. In the fourteenth century, accidents such as the plague pruned the princely line of the Daniilovichi to a single stem through which all its wealth flowed. Between 1353, when Ivan II succeeded his brother Simeon, and 1425, no younger brothers would survive to challenge the succession of a dying prince's sons. Dmitrii Donskoi (r. 1362–1389) shared the principality only with his cousin, Vladimir Andreevich, and the two ruled amicably, with Vladimir Andreevich recognizing the sovereignty of his cousin and loyally handing on his shares of the Jochid tribute.40

By 1400, Moscow was by far the wealthiest, the largest, and the most powerful of the Rus’ principalities. Its growing military power first became apparent in 1380 at the battle of Kulikovo against Emir Mamaq. However, Toqtamish's devastating raid in 1382 showed that Moscow was still weaker militarily than a declining Golden Horde. Moscow also lacked the reach or influence or prestige of Lithuania, which now controlled most of the Rus’ principalities along the Dnieper, including Kiev. Indeed, Lithuania would remain the dominant power in the west until the second half of the fifteenth century. As we have seen, Prince Vasilii I of Moscow (ruled 1389–1425) accepted the suzerainty of Vitautas, his father-in-law and Lithuania's ruler for several decades.

MOSCOW, 1400–1500: CIVIL WAR AND REUNIFICATION

During the long reign of Vasilii II (1425–1462), the cohesion of Moscow's elite was tested and tempered during a vicious succession struggle between two branches of the Daniilovichi. In 1432, Khan Ulugh-Muhammad of the Great Horde (the eventual founder of the Kazan’ khanate) granted the title of grand prince to Vasilii II, the son of Vasilii I. However, for the first time since 1353, a brother, Yurii of Galich, had survived the dying prince. He seized the throne in 1433. But he failed to gain the support of Moscow's boyars and other leaders, and was forced to return the principality to Vasilii. Over the next 20 years, a series of similar contests showed that Vasilii II enjoyed widespread support within the boyar elite, despite his limited political and military skills. When Vasilii II died in 1462, he had no surviving brothers and his son, the future Ivan III, inherited the throne unchallenged.

The civil wars of the mid-fifteenth century mark a critical turning point in the building of a Muscovite mobilizational machine. They were fought with traditional princely and boyar retinues, but by their end the prince of Moscow was beginning to concentrate large military forces in his own hands.

The war destroyed Vasilii's most powerful rivals for the title of grand prince and led to the annexation of their patrimonies and the takeover of their retinues. Other princes, already weakened economically through generations of partible inheritance, now found their lands so devastated they had little choice but to become vassals of the prince of Moscow. The few remaining independent princes were forced to pay Moscow a heavy tribute that left them too little revenue to maintain sizeable military retinues; Tver’ principality, once Moscow's most serious rival, could no longer field more than 600 men.41

Independent princes offered their service to Moscow's grand prince, and service soon turned into vassalage, as the wealth of former princes dwindled and that of Muscovy grew.

After his return to Moscow in 1447, Vasilii II issued coins proclaiming himself “sovereign of all Rus’.”42 In 1452 he established a client Tatar state, the khanate of Kasimov, on the border with Kazan’, for Kasim, a son of Ulugh-Muhammad of Kazan’, who had sought service with Muscovy. This gave Muscovy loose claims on the khanate of Kazan’ that would be cashed in a century later by Ivan IV. Vasilii II also created a closer relationship with the Orthodox Church, after appointing a new Metropolitan, Iona of Riazan’, in 1448 without consulting Constantinople. When Constantinople fell in 1453, this decision began to look like a remarkable act of foresight. The Russian Orthodox Church was now independent of all foreign authority, allowing an eventual convergence of religious and national identities that would resonate with all levels of Russian society.

When he died in 1462, Vasilii II passed the title of grand prince to his heir, Ivan III, without seeking Tatar consent. He was the first grand prince to do so. In his will, he enhanced his son's power by granting him more than half of his own lands, including the most populous and wealthiest parts of Muscovy.43 These steps towards a new principle of inheritance in the senior line can be traced in princely testaments from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries.44 They ensured that Muscovy, unlike so many of its rivals, would not divide its wealth and power each time a prince died, enabling it to eclipse principalities that persisted with such practices.

Ivan III ruled for 43 years from 1462 to 1505, and was succeeded by his son, Vasilii III (1505–1533). During these two reigns, Muscovy became a major political, economic, and military power. Sustained territorial expansion demonstrated and enhanced Muscovy's power, increasing its population, its economic and commercial resources, and its ability to attract wealthy and loyal servitors. In 1300, Moscow controlled less than the 47,000 sq. kilometers of today's Moscow oblast’. By the accession of Ivan III in 1462, it ruled c.430,000 sq. kilometers, or almost 10 times as much. At the death of Vasilii III in 1533, Muscovy ruled c.2,800,000 sq. kilometers, almost seven times the territory inherited by Ivan III.

Moscow conquered Riazan’ between 1456 and 1521. Iaroslavl’ was conquered in 1463; Perm in 1472; Rostov in 1474. Novgorod, by far the largest of these acquisitions, was conquered in 1478, giving Moscow access to vast territories in the north, and control over the fur trade. Its old rival, Tver’, was conquered in 1485. During the reign of Vasilii III, Muscovy gobbled up Pskov (1510), Smolensk (1514), and the last parts of Riazan’ (1521), enhancing its control over trade routes west to Poland and south to the Black Sea.

Under Ivan III, Muscovy became a fully independent state. At his accession, Ivan did not seek the blessing of Saray, nor did the khan of the Great Horde attempt to grant it. This was the first time since Batu's invasion, 225 years earlier, that a grand prince had not been confirmed in office by Tatar overlords. In 1480, Khan Ahmed of the Great Horde led an army north to reimpose Saray's authority. He found a Muscovite army waiting at the crossing on the Ugra river. Michael Khodarkovsky reconstructs what happened next:

Crossing rivers had always presented a serious logistical challenge to nomadic cavalry even when the foe was not in sight. With the Muscovite troops already positioned at the known fords, such a crossing would have been extremely hazardous. Ahmad chose to wait for the arrival of his ally, King Kazimierz of Poland. But the king's troops never arrived, because they were tied up by the campaign of [Ivan's ally, the Crimean khan] Mengli Giray in the southern regions of Poland-Lithuania.45

Ahmed waited three months. But by November the weather was turning and local pastures were exhausted. He may also have heard of Nogai attacks on the Horde's lands, possibly launched with Moscow's encouragement. So he withdrew. His retreat ended the last attempt of a steppe khanate to impose its authority on Moscow. Ever since, the so-called “stand on the Ugra” has been seen as a symbol of Moscow's emancipation from Tatar rule.

Three months later, Ahmed died in battle with the Nogai. But the Great Horde was already in trouble, threatened not just by a rising Muscovy, but also by the Nogai, who were threatened in turn by the Uzbek and Kazakh hordes, and by Crimea to the west. In 1502 Crimean armies destroyed the Great Horde, and the Crimean khanate could now claim to be the legitimate heir of the Golden Horde.

After 1480, Moscow renounced its obligation to pay tributes to the Great Horde, so that the entire tribute, and the elaborate machinery built up to collect it, was from now on used to support the principality of Moscow. Ivan kept paying smaller tributes to other khanates, including Crimea and Kazan’, though they looked increasingly like subsidies.46 Ivan certainly understood the symbolic significance of these changes, for he began styling himself “Tsar” or Caesar. Vasilii III reverted to the title of Grand Prince, partly because no other government recognized the new titles, but his successor, Ivan IV, would reassume the title of Tsar at his coronation in 1547.

BUILDING THE ARMY

How did Muscovy achieve such a powerful position? Sustained territorial expansion depended on the efficient transmutation of land, people, and resources into military power. At Ivan III's accession in 1462, mobilizing an army still meant asking boyars, princes, and other allies to deliver troops. The grand prince had direct control only over his own household forces, and those of his closest boyars, who brought their own followers, their dvoriane and deti boiarskie. When necessary, princes could also summon a peasant militia.47 These were unreliable ways of forming armies. There was no guarantee that the required forces would show up or that they would obey the prince's commands if they did appear. Nevertheless, the growing size of the Muscovite elite group and the increasing willingness of neighboring princes to ally with and ingratiate themselves with Moscow's princes ensured that even these crude methods could generate substantial armies.

Under Ivan III and Vasilii III, the size, power, discipline, and organization of the army increased significantly. Territorial expansion provided new lands that could be offered as estates to attract servitors from other principalities, or from Lithuania or the Tatar khanates. By the late fifteenth century, Tatars made up a significant group of servitors. They included for a while the disgruntled brothers of the Crimean khan, Mengli-Giray. Tatars commanded Tsarist troops in battles against Kazan’ and the Great Horde, and in 1471 a Tatar Tsarevich Danyar commanded a unit attacking Novgorod.48 New lands could also be used to pay princes and boyars serving as local governors or namestniki. As they submitted to the grand prince, former princes and boyars were fitted into an elaborate system of family precedence, or mestnichestvo, that preserved a symbolic sense of family honor and rank even as new arrivals lost their political and military independence.

The most effective way of using new land was to offer it (and the peasants who farmed it) to cavalrymen in return for military service. This was a natural extension of the ancient tradition of kormlenie, or “feeding,” under which officials were allowed to “feed” off the areas they were administering, as in the following charter from Ivan III.

I, Grand Prince Ivan Vasil'evich of all Russia, have granted to Ivan, son of Andrei Plemiannikov [the villages of] Pushka and Osintsovo as a kormlenie with the right to administer justice [pravda] [and collect fees for this service] and to collect taxes on the purchase, sale, and branding of horses.49

Similar methods were familiar in the steppes, where powerful khans routinely allocated pasturelands in return for military service. Chinggis Khan had done just this at the great quriltai of 1206, as had Batu soon after 1240. The system of granting land in return for military service may also have been modeled on the iqta of the Islamic world. Ivan's father, Vasilii II, had occasionally rewarded servitors with temporary grants of settled land. But it was Ivan III who turned these ad hoc experiments into the foundations of an increasingly powerful army and state.

In Muscovy, land grants in return for military service came to be known as pomest'e. Territorial expansion provided the necessary land.50 After conquering Novgorod, Ivan III confiscated over a million hectares of land from its nobles and churches, and settled 2,000 Muscovite servitors on these lands in return for military service. The same system was also introduced in Pskov, Riazan’, Smolensk, and other newly annexed lands. It was particularly effective at expanding the armies on Moscow's western borders, which helps explain Russia's military successes in this region in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, when Moscow conquered Novgorod, Pskov, Smolensk, and Chernigov.51

At little cost, the pomest'e system increased both the size and discipline of the army.52 But it also required an expansion of the princely bureaucracy beyond the level of household management. From 1499, government officials began keeping lists of who was liable for service, in an office that would become the formidable pomestnyi prikaz after 1550. The Kazan’ campaign of 1467, the first military campaign for which we have detailed reports, showed the emergence of a new type of military bureaucracy. The grand prince remained behind the battlefield, taking care of grand strategy, while commanders or voevody directed the battle. Preparations for mobilization were careful, and the army set off with a detailed plan of action. The “staff work” for the campaign was meticulous.53 Such planning would have been impossible without the increased discipline of the pomest'e system.

Nevertheless, we should not exaggerate the size of Moscow's armies. In the late fifteenth century, most mobilizations were still small scale. Until 1512, when the government began placing regiments in forts along the Ugra and Oka rivers and their fords, mobilization normally meant creating small armed contingents to defend fortified points along major invasion routes. Despite contemporary claims to the contrary, it is unlikely that Muscovite armies were larger than about 35,000 men before the late sixteenth century.54

A second crucial change was technological. In the late fifteenth century, for the first time, gunpowder technologies began to affect warfare in Inner Eurasia. Gunpowder had been used in warfare in China since the tenth century in the rudimentary forms of incendiaries, but when it arrived in Europe, it was already in the more developed form of an explosive to be used in cannon or guns. There is little evidence on the routes by which the technology was transmitted, but it almost certainly arrived through the Mongol Empire, and the first unequivocal illustration of a gunpowder weapon in Europe comes from the 1320s.55 Muscovite armies first encountered firearms while besieging Bulghar in 1376. These weapons may have come from Central Asia, where Timur began to use them at about this time. Moscow imported cannon, apparently from Bohemia (the words “pushka” and “pishchal’,” both referring to light cannon, are of Czech origin), and used them to defend Moscow against Toqtamish in 1382.56 By the early fifteenth century, both Moscow and Tver’ manufactured firearms. But it was under Ivan III that Muscovite armies began to use gunpowder weapons more systematically.57 Ivan III invited Italian arms makers to Moscow, using connections made through his marriage to Sophia Paleologa (the niece of the last Byzantine emperor), and in 1494 a cannon- and powder-making factory was established in Moscow. At first cannons were used mainly as fixed defenses or in sieges. Not until the 1520s would they be used in battle.58 Ivan also hired Italian military architects to rebuild the Kremlin's fortifications as his enemies, too, began to use cannon in sieges.

At first, gunpowder weapons had limited impact, particularly in the steppes. Muskets were inaccurate and slow to load, and cannons were dangerous (if badly made they exploded), and hard to move and aim. In the steppes, cavalry, bows and arrows, and swords retained their advantage much longer than in Europe.59 The main role of cannon on Muscovy's steppe frontiers was defensive. Steppe armies found it much harder to capture cities with cannon and modern defenses, which ruled out the sort of campaign that Batu had launched. As Khodarkovsky points out, “In 1500 the Crimean troops burned the suburbs of several Polish towns but could not capture them, just as the large Crimean army that reached Moscow in 1571 failed to take the city.”60 Increasingly, steppe armies besieged cities mainly to give themselves a free hand as they captured slaves and livestock from the surrounding countryside.

On Muscovy's steppe frontier, forts and fortification lines became increasingly important, as cannons and modern fortifications improved their defenses, and as Muscovy acquired the wealth necessary to build more forts and longer fortified lines. The main role of forts was “interdiction” – barring the way to steppe raiding parties, whether large or small, and cutting off their lines of retreat. Since Kievan times, princes of Rus’ had built fortified lines consisting of earthworks and small forts designed to block familiar invasion routes, particularly at key crossing points across major rivers. By the end of the fifteenth century, there was a long line of fortified points along the Oka river, defended by annual musters of troops. Indeed, under Ivan III and Vasilii III, the most expensive military activity may have been the building of frontier fortresses, though much of the cost was passed on to the frontier populations in the form of corvée labor.61 Over the next two centuries, building fortified lines would become the most important single way of advancing the frontier.

A defensive line consisted of fortified towns established in a line at strategic points near river junctions, fording places, or at likely portages. Forts were surrounded with long palisades, trenches, and earthworks. At each fort a garrison of troops was stationed under a military governor (voevoda), who held civil authority as well as command of the military. Between strongpoints outposts of various sizes filled in the line. Further out in the steppe areas advanced observation towers served as lookouts to give warning of approaching hostile parties.62

MUSCOVY: A RISING POWER

Increasing mobilizational power paid for Moscow's increasingly powerful armies and fortifications.

As long as Moscow was allied with the Crimea, relative freedom from slave raids stimulated economic growth. Populations grew, and by the mid-sixteenth century three-field rotations were common particularly in the more populous central regions.63 The pomest'e system probably encouraged agricultural intensification as landlords and government officials increased fiscal pressure on peasants.64 Peasants, in turn, put pressure on the land, the forests, and rivers.65 They worked arable land more intensively; they grazed more livestock on meadowlands; they exploited rivers for their fish, and forests for their furs, timber, firewood, honey, and wax. In these ways, mobilizational pressure was transmitted downward through Muscovy's class system to Muscovy's fragile ecological base in the land, the rivers, and the woods. Without abundant surplus land, such pressure would soon have exhausted Muscovy's thin soils, leading to depopulation and eventual decline. This is one more reason why territorial expansion was so crucial to mobilization. With more land, Muscovy's princes could turn the fiscal screws without destroying the principality's fragile ecological foundations.

Territorial expansion grew Muscovy's economy in other ways, too. The conquest of Novgorod gave Moscow access to rich commercial networks linking the Baltic, Lithuania, and Europe to the fur quarries of Siberia and the far north.66 The conquest of Novgorod also encouraged expansion to the north and north-east. In 1499 Moscow conquered the lands of the Yugrians and Voguls. The following account suggests the methods they used in this early experiment in northern colonization.

In November and December of 1499 three of [Ivan III's] generals, with 5000 men, after building a fortress on the Pechora, crossed the Ural on snow-shoes, in the face of a Siberian winter, and broke with fire and sword upon the Yugrians of the Lower Ob. The native princes, drawn in reindeer sledges, hurried to the invaders’ camp to make their submission; the Russian leaders scoured the country in similar equipages, their soldiers following in dogsledges. Forty townships or forts were captured; fifty princes and over 1000 other prisoners were taken; and Ivan's forces, returning to Moscow by the Easter of 1500, reported the entire and final conquest of Yugrians and Voguls.67

But profiting from the fur quarries of the north was difficult, because Muscovy still had limited access to the Baltic and Europe. In the late fifteenth century, Muscovy controlled a narrow strip of land near the Neva river (near modern St. Petersburg), which could be reached along the Volkhov river. By the 1480s the value of this route had declined as ships (particularly those of the Dutch) grew too large to navigate the Volkhov. Muscovite merchants now had to trade with Europe though Reval or Narva, whose rulers imposed heavy tolls on Muscovite goods.68 Gaining a Baltic port that would allow Moscow to increase trade with Europe's booming economy became a central aim of Muscovite military and diplomatic policy for the next two centuries.

To the south, Muscovy took over the entrepreneurial role once played by Saray. Huge trade delegations traveled along the Don or through the steppes to Moscow to exchange horses and other livestock produce for furs and forest goods.69 In 1486, a Greek employed by the grand prince reported to the duke of Milan that

[certain provinces] give in tribute each year great quantities of sables, ermines, and squirrel skins. Certain others bring cloth and other necessaries for the use and maintenance of the court. Even the meats, honey, beer, fodder, and hay used by the Lord and others of the court are brought by communities and provinces according to certain quantities imposed by ordinance …70

The importance of these southern trade networks helps explain why Muscovy and Lithuania competed so fiercely to control trade routes through Ukraine along the Dnieper.

The pomest'e system played an increasingly important mobilizational role from the late fifteenth century. If it was to work, peasants had to supply servitors with food, horses, cash, and recruits, so that mid-level servitors could build their own petty mobilizational machines. They could only do so if the government helped them bind peasants to the land, making it difficult to flee even the most predatory of landlords. As early as 1497, in the first law code to apply to the whole of Muscovy, peasants were forbidden to leave their lands before paying all outstanding dues and loans. Even then, they were only allowed to leave around St. George's Day (November 26), just after the harvest.

Elite demands on the rural population took many forms.

In one contract with the monastery on whose manor they lived, the peasants undertook to perform a wide variety of services, including cultivating the monks’ fields, mowing their hay, repairing their fences, building their weirs, weaving their fishing-nets and baking their bread. Under other arrangements, peasants gave their lords specified amounts of rye and oats, butter, cheese, flax and a small amount of money. By the end of the fifteenth century, such cash payments often formed part of the peasants’ dues.71

Expansion and fiscal and bureaucratic reforms allowed the princes of Moscow to mobilize cash as well as men and resources. Immunity grants list judicial fees that had been levied by princes since the Middle Ages, duties on trade, levied at the entrances to towns or at transit points such as river crossings, and many forms of labor service to support local officials or to build and maintain roads or fortifications.72 But cash revenues had limited importance before the middle of the sixteenth century, and the pomest'e system covered many of the costs of forming and equipping Muscovy's armies.

Moscow city was transformed. Fourteenth-century Moscow had a population of less than 20,000 people. I. E. Zabelin remarked that it resembled a “gentleman's country estate.”73 The most important building was the prince's fortress, the Kremlin, where the prince lived with his family and leading nobles, churchmen, officials, and merchants. The rest of the town extended little more than a kilometer or two from the Kremlin. Then you reached forest lands with small villages of just a few households.74 In the fifteenth century, the city grew fast. In the early sixteenth century, Moscow may have been bigger than London. According to Alef, its size owed less to its commercial than to its political and ecclesiastical importance, and the desire of princes and bishops and merchants to build impressive palaces and churches. Ivan III renovated the Kremlin and the city, with the help of Italian architects.75

The speed of Moscow's rise to power is a reminder that, under Inner Eurasian conditions, slight advantages accrued to the most powerful states in powerful positive feedback cycles. Wealth attracted servitors, who served in Muscovy's growing armies, which conquered new lands and generated even more wealth. None of this could work without luck, skillful leadership, and a high degree of elite solidarity. But elite discipline was a brittle resource. It had to be nurtured and maintained with care and skill because splits at the top could easily crack the entire system apart. The critical role of leadership in lands with limited surpluses surely helps explain the emergence and persistence of Muscovy's increasingly autocratic political culture.

Through loyal service to its Mongol overlords, careful husbanding of their human and territorial resources, a willingness to learn from their Mongol overlords, and a large dose of luck, the princes of Moscow had managed to create a principality far larger, more unified, and more powerful than any other in the former lands of Rus’. To a remarkable degree they had met the daunting challenge of building and managing an agrarian smychka that would allow them to defend their agrarian lands against the military power of their steppe neighbors. By 1500 Muscovy was a major international power. In the next century, it would build on that power. But it would also come close to collapse before achieving in the seventeenth century a hegemony over much of western and central Inner Eurasia.

NOTES

REFERENCES

- Ágoston, Gabor. “Ottoman Warfare in Europe 1453–1826.” In European Warfare, 1453–1815, ed. Jeremy Black, 118–144. Houndmills and New York: Macmillan, 1999.

- Alef, Gustave. “The Origins of Muscovite Autocracy: The Age of Ivan III.” Forschungen zur osteuropäischen Geschichte. Wiesbaden: Osteuropa-Institut, 1986.

- Alekseev, Yu. G. Gosudar’ Vseya Rusi. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1991.

- Andrade, Tonio. The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation and the Rise of the West in World History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Beazley, C. Raymond. “Russian Expansion in the Middle Ages.” In Russia's Eastward Expansion, ed. G. A. Lensen, 3–7. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1964.

- Birnbaum, Henrik. Lord Novgorod the Great: Essays in the History and Culture of a Medieval City-State, vol. 1. Columbus, OH: Slavica, 1981.

- Bushkovitch, Paul. The Merchants of Moscow, 1580–1650. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

- Childs, John. “The Military Revolution 1: The Transition to Modern Warfare.” In The Oxford Illustrated History of Modern War, ed. Charles Townshend, 19–34. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Crummey, R. O. The Formation of Muscovy, 1304–1613. London and New York: Longmans, 1987.

- Davies, Brian L. “Development of Russian Military Power, 1453–1815.” In European Warfare, 1453–1815, ed. Jeremy Black, 145–179. Houndmills and New York: Macmillan, 1999.

- Davies, Brian L. Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe, 1500–1700. London and New York: Routledge, 2007.

- Donnelly, Alton. “The Russian Conquest and Colonization of Bashkiria and Kazakhstan to 1850.” In Russian Colonial Expansion to 1917, ed. M. Rywkin, 189–207. London: Mansell, 1988.

- Etkind, Alexander. Internal Colonization: Russia's Imperial Experience. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012.

- Fennell, J. L. A History of the Russian Church to 1448. London and New York: Longman, 1995.

- Fennell, J. “The Tver Uprising of 1327: A Study of the Sources.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 15 (1967): 161–179.

- Fisher, Alan. The Crimean Tatars. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1978.

- Halperin, Charles J. Russia and the Golden Horde: The Mongol Impact on Medieval Russian History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985; London: I. B. Tauris, 1987.

- Halperin, Charles. The Tatar Yoke. Columbus, OH: Slavica, 1986.

- Hellie, R. Enserfment and Military Change in Muscovy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971.

- Hellie, R. “Russia, 1200–1815.” In The Rise of the Fiscal State in Europe, c. 1200–1815, ed. Richard Bonney, 481–505. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Keenan, Edward L. “Muscovy and Kazan’: Some Introductory Remarks on the Patterns of Steppe Diplomacy.” Slavic Review 27 (1967): 548–558.

- Keenan, Edward L. “Muscovite Political Folkways.” Russian Review 45, No. 2 (April 1986): 115–181.

- Khodarkovsky, Michael. Russia's Steppe Frontier: The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1500–1800. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2002.

- Kivelson, Valerie. “Merciful Father, Impersonal State: Russian Autocracy in Comparative Perspective.” In Beyond Binary Histories: Re-imagining Eurasia to c. 1830, ed. V. Lieberman, 191–219. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

- Kollmann, Nancy Shields. By Honor Bound: State and Society in Early Modern Russia. Ithaca, NY and London: Cornell University Press, 1999.

- Kollmann, Nancy Shields. Kinship and Politics: The Making of the Muscovite Political System 1345–1547. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1987.

- Lieven, Dominic. Empire: The Russian Empire and its Rivals. New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Lindner, Rudi. “How Mongol Were the Early Ottomans?” In Mongols, Turks and Others: Eurasian Nomads and the Sedentary World, ed. Reuven Amitai and Michal Biran, 282–289. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2005.

- Lukowski, J. and H. Zawadski. A Concise History of Poland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Martin, Janet. Medieval Russia, 980–1584, 2nd ed. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Martin, Janet. “North-eastern Russia and the Golden Horde.” In Cambridge History of Russia, Vol. 1: From Early Rus’ to 1689, ed. Maureen Perrie, 127–157. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Martin, Janet. “The Emergence of Moscow (1359–1462).” In Cambridge History of Russia, Vol. 1: From Early Rus' to 1689, ed. Maureen Perrie, 158–187. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Martin, Janet. Treasure of the Land of Darkness: The Fur Trade and its Significance for Medieval Russia. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Nasonov, A. N. Mongoly i Rus’. The Hague: Mouton, 1969.

- Ostrowski, Donald. Muscovy and the Mongols: Cross-Cultural Influences on the Steppe Frontier, 1304–1589. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Ostrowski, Donald. “Ruling Class Structures of the Kazan’ Khanate.” In The Turks, ed. Hasan Celâl Güzel, C. Cem Oğuz, and Osman Karatay, 6 vols., 2: 841–847. Ankara: Yeni Türkiye, 2002.

- Ostrowski, Donald. “Simeon Bekbulatovich.” In Russia's People of Empire: Life Stories from Eurasia, 1500 to the Present, ed. S. M. Norris and W. Sunderland, 27–35. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012.

- Ostrowski, Donald. “The Growth of Muscovy (1462–1533).” In Cambridge History of Russia, Vol. 1: From Early Rus’ to 1689, ed. Maureen Perrie, 213–239. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Ostrowski, Donald. “Troop Mobilization by the Muscovite Grand Princes.” In The Military and Society in Russia, 1450–1917, ed. Eric Poe and Marshall Lohr, 19–40. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2002.

- Richards, John F. The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

- Roublev, Mikhail. “The Mongol Tribute According to the Wills and Agreements of the Russian Princes.” In The Structure of Russian History: Interpretive Essays, ed. Michael Cherniavsky, 29–64. New York: Random House, 1970.

- Rowell, Stephen C. Lithuania Ascending: A Pagan Empire in East-Central Europe, 1295–1345. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Smith, R. E. F. Peasant Farming in Muscovy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

- Stevens, Carol B. Russia's Wars of Emergence 1460–1730. Harlow: Pearson, 2007.

- Subtelny, Orest. Ukraine: A History, 4th ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

- Tucker, Robert C., ed. The Marx–Engels Reader, 2nd ed. New York and London: W. W. Norton, 1978.

- Vernadsky, G. V. The Mongols and Russia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1953.

- Vernadsky, G. V.et al., eds. A Source Book for Russian History from Early Times to 1917, 3 vols. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1972.