[8]

1600–1750: A TIPPING POINT: CENTRAL AND EASTERN INNER EURASIA BETWEEN RUSSIA AND CHINA

Modern maps that show great swaths of colored territory as clearly belonging to one or another khanate, kingdom, principality, or empire are fundamentally misleading about the real nature of sovereignty on the ground. The goal of any political power was to control the locus of extraction, such as a key bridge, port, mountain pass, or fortress.1

[H]ere it is not like in Russia, they [the Kazakhs] do not obey my orders.

Abulkhair, khan of the Kazakh Lesser Horde (r. 1718–1748)2

The rise of a new hegemonic power in the West had consequences that rippled through all of Inner Eurasia. But in the Far East, communities faced another rising power in Qing China. Over time, Muscovy and China would become the primary engines of change in Inner Eurasia, but the full impact of their power would not become apparent until the eighteenth century.

This chapter will describe changes between 1600 and 1750 in Siberia, in the pastoralist societies of Mongolia, Xinjiang, and the Kazakh and Pontic steppes, and in the more urbanized societies of southern Xinjiang and Transoxiana. With the exception of Transoxiana, this is when most regions of Inner Eurasia east of the Volga began to look like colonies of either Russia or China. In Siberia, Muscovite expansion crushed local communities, transforming them demographically, economically, culturally, and politically. By 1750, Siberia was already looking like a “neo-Europe”: a colony dominated by arrivals from the imperial heartland.3 Other regions of Inner Eurasia would also be transformed, but less fundamentally. They preserved their cultural traditions more successfully because they were never swamped demographically, so (with the near exception of Kazakhstan) they did not become “neo-Europes.”

But the expansion of Muscovy and China narrowed their options. In the seventeenth century, the conquest of Siberia tripled the area of Muscovy. (See Figure 6.2.) Under the Qing, the Chinese Empire almost doubled in size as it incorporated Xinjiang and eastern and western Mongolia. Indeed, Qing expansion was almost as dramatic as that of the Russian Empire. In western Mongolia, the Qing conquest of Zungharia in the mid-eighteenth century destroyed the last of the great steppe empires. In eastern Mongolia, in Xinjiang, in the Kazakh steppes and Central Asia, pastoral nomadic communities survived, but with greatly reduced power and independence.

MUSCOVITE EXPANSION INTO SIBERIA AND FIRST CONTACTS WITH CHINA

The Muscovite conquest of Siberia was rapid and similar to European expansion in North America. But there was also a crucial difference. European expansion created overseas empires, while Muscovy bordered on Siberia so its expansion created a single contiguous empire.

In 1600, Siberia's indigenous population probably numbered no more than 200,000.4 Had they not been protected by remoteness, they might have been conquered earlier by Türks, Tatars, Mongols, or Chinese. In fact, their contacts with these peoples were limited to the borderlands of southern Siberia, and had been confined to trade, occasional payments of tribute, and the odd military conflict. Moscow's intervention in Siberia was on a larger scale and much more dangerous, and its impact would prove as destructive and irreversible as European colonization of the Americas.

Muscovite traders and soldiers entered Siberia in pursuit of furs, a revenue stream that had lured the princes and merchants of Rus’ since the Middle Ages. In 1600, furs contributed almost 4 percent of Muscovy's income; by the middle of the seventeenth century, they accounted for 10 percent.5 Moscow's interest in Siberian furs and other resources increased after it conquered the Kazan khanate and the Volga river.6 In 1558, Tsar Ivan granted the Stroganov family of merchants monopoly rights over the resources of the upper Kama river. The royal charter specifically invited them to prevent the “Siberian Sultan” from stopping “our Ostiaks and Voguls and Ugrians from sending tribute to our treasury.”7 The Stroganovs mined iron and copper, and the salt of Solikamsk (“Salt-on-the-Kama”). They helped fund Ivan IV's Livonian war, which earned them royal patronage, but also made commercial sense given the importance of European commercial outlets for goods acquired in the East. Because their operations in eastern Muscovy had always required armed guards, the Stroganovs, like the merchant companies of Europe, were used to managing soldiers, and they did so under royal charters allowing them to occupy, exploit, and settle “empty” lands east of the Urals, along the Kama, Tobol, Irtysh, and Ob rivers. They used their private armies to extract tributes in furs from native populations of Voguls and Ostiaks.

In 1563, with Nogai support, a Kazakh leader, Kuchum, seized power from the khan of Sibir and took control of the rich fur tributes of western Siberia, drained by the Ob and Irtysh rivers. Kuchum refused to pay Moscow the tributes it had received from his predecessor. In about 1581, the Stroganovs invaded the khanate of Sibir from a base in Tiumen’, with an army of 500 Cossacks led by a former pirate, Ataman Ermak.8 By the end of 1583, Ermak's small army had defeated Kuchum at his capital, Isker, near modern Tobolsk. They secured the Tsar's reluctant blessing for the enterprise with a gift of 2,400 sables, 800 black fox furs, and 2,000 beaver pelts. Almost immediately, Tsar Ivan added to his many titles that of “Tsar of Siberia.”9 Within two years, Ermak himself, and most of his men, had succumbed to a grueling guerrilla counter-attack. Ermak drowned in the Irtysh river in 1585, fleeing from an ambush.10

Soon other armed groups from Muscovy secured control of the Irtysh river and began building forts (ostrogi) throughout western Siberia, as Kuchum's power and prestige evaporated. The most important new fort was at Tobolsk. In 1601, Mangazeia was founded in the heart of Samoyed territory, giving access to the Yenisei river system. In 1604 Tomsk was founded on the Tom, a tributary of the Ob river system. By 1620 there were already 50 fortified settlements in Siberia. The pattern of control established early in the seventeenth century would be reproduced many times. As military bases, forts could be used in defense or during pacification campaigns. But they also functioned as customs posts, choke points, and warehouses for the tribute or iasak. Soon, like the forts of the Pontic steppes, they began to attract peasant migrants. Within 50 years, this expanding network of strongpoints and safe houses would embrace most of Siberia (Map 8.1).

Map 8.1 Russian conquest of Siberia along riverways. Rywkin, Russian Colonial Expansion to 1917, 71.

Colonization paid handsomely, even in the inhospitable far north, where the furs were thicker and more valuable, and could be transported by sea to Archangel. Fur revenues increased by three times between 1589 and 1605, and eight times more by the 1680s.11 Such vast profits drove expansion even during the Time of Troubles, luring merchants and soldiers further east as local supplies of high-quality furs were exhausted. By the middle of the seventeenth century, supplies of furs were already declining in western Siberia, along the Yenisei by the 1670s, and in Yakutia by the 1680s, driving Muscovite fur traders further and further east into what would eventually be known as the Far East.

Turukhansk, the first large fort on the Yenisei river, was founded in 1607. (It would later become a place of exile, with many distinguished “guests,” including Stalin.) Novokuznetsk (Kuznetsky Ostrog) was founded in 1618 on the Tom river, in what is today a major coal mining region, the Kuznetsk basin or Kuzbass. Yeniseisk was founded in 1619 where the Yenisei joins the Tunguska, a tributary flowing from Lake Baikal. Lake Baikal was reached in 1631 and Yakutsk was founded in 1632 on the next major river system, that of the Lena. The vast Lena system of rivers dominated what came to be known as eastern Siberia, whose main city, Irkutsk, was founded in 1652. In 1641, a detachment of Cossacks under Ivan Moskvitin reached the Sea of Okhotsk. By 1690 Muscovy controlled most of far eastern Siberia, with the exception of the Amur region, Kamchatka, and Chukhotka.

The arrival of Muscovite merchants and soldiers transformed Siberia fast. In 1600 just a few thousand Russians lived in Siberia. By 1700, there were at least as many immigrants from Russia as there were indigenous Siberians, perhaps as many as 200,000 or 300,000.12 For millennia, Siberian communities had been largely independent, whether in the vast coniferous forests or taiga, or in the tundra lands of the far north where many herded reindeer. Now, within just a century, one of the largest regions of Inner Eurasia had been incorporated within a single empire. The Muscovite conquest of Siberia was as astonishing (and as destructive) as the creation of the Mongol Empire or the Spanish Empire in the Americas. And, as in the Americas, diseases such as smallpox, typhus, and syphilis often proved more ruinous to local populations than military conquest.

Merchants and officials had many ways of extracting furs.13 They included gift exchanges, the taking of hostages, intervention in local feuds, which encouraged local groups to help Muscovite forces against their own enemies, and all the myriad tricks of colonialism in regions without complex state structures. The government secured furs through a 10 percent levy on the fur trade. But it also traded furs on its own account, and on privileged terms. The simplest way of extracting furs was also the oldest: Muscovite officials inserted themselves within ancient networks of tribute or iasak. They demanded between 1 and 12 sable pelts (or their equivalent) from every male over 15, required oaths of loyalty, and took chiefs or their family members as hostages to ensure payment.14

This was resource mobilization of the most brutal kind – Siberia's equivalent to serfdom, which was never formally imposed on the region. And, just as wealthy landlords understood the value of treating their serfs well, so, too, Muscovite officials understood that, if used too crudely, the iasak system could ruin potential tax payers, so they continually exhorted officials to treat the natives kindly. Such exhortations had little effect because officials in Siberia knew that their own fate depended on the size of the tributes they exacted. But for the government, Siberian iasak payers were as important, in their way, as Russian tax payers, and sometimes Muscovite courts came down heavily on Russians who abused natives.15

Until the time of Peter the Great, no systematic attempt was made to civilize, Europeanize, or Christianize the local population. Formal missionary work began only in the early eighteenth century, when Peter appointed a bishop of Tobolsk, who was told to destroy pagan idols and baptize the local Ostiak people.16 Peter ordered the shaving of beards and the introduction of European clothing, civilizing projects that he had also imposed on his Russian subjects. In remote regions, conversion, like the payment of tributes, was often enforced by the crudest of means. One priest, Father Pykhov, described some of his methods:

In the last year of 1747, … I beat the new Christian, Ostiak Fedor Senkin, with a whip, because he married his daughter off at the said time and celebrated the wedding feast during the first week of Lent. I also beat his … son-in-law with a whip, because he buried his deceased son himself, outside of the church and without the knowledge of the priest. … Semen Kornilov Kortyshin was beaten with a whip because he never went to the holy church … I also beat the widow Marfa and her son Kozma with a whip … because … they kept in their tent a small stone idol, to whom they brought sacrifices.17

Locals claimed that, if offered a large enough bribe, the same priest often permitted traditional funerals.

Cossacks, officials, and merchants were followed by peasant farmers and exiles, and as early as the late seventeenth century, peasants (or farming Cossacks) outnumbered other groups of immigrants. The government was keen to settle peasants mainly to supply local garrisons and officials with food. But their arrival disrupted the lives of indigenous populations as they plowed up traditional hunting lands and introduced terrifying new diseases.18 Peasant migrants generally brought the lifeways, agricultural methods, and housing styles of their Russian or Ukrainian homelands, so that Siberian villages often looked like villages in Inner Eurasia's western heartland.

Many settlers were simply ordered to Siberia. These included Cossacks, many of whom settled permanently, and foreign prisoners of war, often known as “Lithuanians” because so many came from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In the seventeenth century, Siberia began to be used as a place of exile after the 1649 law code formalized Siberian exile as a punishment for criminal offenses. In the second half of the century, almost 30,000 people were exiled to Siberia. Other settlers fled the increasingly onerous burdens of serfdom to become Siberian “state peasants.”19 Old Believers also fled to Siberia, though many were sent as exiles, including the most famous religious dissident of the period, Avvakum. One final group of immigrants were women, forced or encouraged to settle in Siberia to correct the extreme gender imbalance among Russian settlers.20

Expansion into Siberia brought Muscovy into contact with new peoples and polities, first the Oirat and Khalkha Mongols, and eventually Qing China.

As early as 1616, Sholoi Ubashi Khunt-Taiji (1567–1623?), a prince of the Khotoghoid Oirat Mongols, asked Muscovy for guns and gunpowder.21 In 1647, Muscovy signed a treaty with the founder of the Oirat (Zunghar) Empire, Erdeni Baatur Khung-Taiji (r. 1635–1653), permitting free trade between Mongols and Siberian natives and agreeing to share the resulting tributes.22

Eventually, Muscovy entered China's sphere of influence and here it met up with another gunpowder empire. The first Muscovite agent to enter China was Ivan Petlin, who traveled from Tomsk to Beijing in 1618.23 Petlin's report, written in 1619, is the earliest surviving Russian eyewitness account of China. The next formal Muscovite mission to China left in 1653, and was followed by two more in 1658 and 1668, led by a Bukharan trader from Tomsk, Setkul Ablin.24 As North American furs glutted European markets, Siberian merchants began to eye the Chinese market. Direct trade between Muscovy and China began from the late 1630s, along several routes. Before 1689, merchants from Muscovy (many of Central Asian origin) traded in the huge market at the salt Lake of Yamysh in Zungharia, where they met Central Asian and Oirat merchants bringing Chinese goods such as silks, linen, rhubarb, tea, and porcelain. From the 1650s goods also began to travel through Irkutsk and Mongolia, and eventually through western Manchuria along tributaries of the Amur river.25

The first military clashes between China and Muscovy occurred in the 1650s, after Erofei Khabarov led an expedition from Yakutsk to the Amur river. Though the battlefield was remote, both armies were equipped with the most up-to-date gunpowder technologies and fortification technologies.26 In 1652, Manchu troops unsuccessfully attacked Khabarov's camp at the abandoned Dahur town of Albazin, and by the 1670s Albazin had become a powerful symbol of Muscovite power in the region. But with both armies at the end of long, fragile, and costly supply lines, diplomacy proved as important as arms. Moscow was more interested in trade than conquest, while the Chinese hoped for Moscow's military neutrality in its looming conflicts with the expanding Oirat Empire (which are described later in this chapter).

Inner Eurasia's two superpowers had a lot to learn about each other. In 1674, Nikolay Gavrilovich Milescu, a Moldavian Greek educated in Constantinople, led a Muscovite embassy to China.27 At the Chinese border he was met by a Chinese official, Mala. The two exchanged diplomatic niceties that illustrate the delicacy of these first diplomatic encounters, and the mutual ignorance of Inner Eurasia's two superpowers. In Beijing, Milescu was presented to Emperor Kangxi. He agreed reluctantly to most Chinese ceremonial demands, including the kowtow, though he insisted on bending down unusually rapidly.28 The Chinese treated the mission with the suspicion they reserved for most trade missions from the steppes.

In 1685, Chinese troops forced the Muscovite garrison at Albazin to surrender. These events were the prelude to the treaty of Nerchinsk, negotiated in August and September of 1689. The treaty marked a fundamental turning point in relations between Muscovy and China and in the history of Inner Eurasia as a whole. As a Mongolian historian has noted, the treaty demonstrated that the steppe heartlands of the regions had now become “a peripheral region lying between two regional world empires.”29 The treaty also began to change the very idea of borders and territoriality throughout eastern and central Inner Eurasia, by introducing for the first time the sedentary ideal of precisely definable borders between polities, borders that could be described by lines on a map.30

China was keen to keep Muscovy neutral after the military victories of the Oirat ruler, Galdan, in 1688, and its officials were beginning to understand the extent of Muscovy's power. At the fortified town of Nerchinsk, the two delegations met in 1689 on terms of scrupulous symbolic equality. Each delegation had exactly the same number of men. Their guards were only allowed to carry swords and were searched for concealed weapons. And the ambassadorial tents were placed so that the ambassadors could each sit in their own tents while they met, which avoided forcing one delegation to visit the other first. The ritual duel continued at the first meeting, on August 22.

The Russians approached the meeting tents with great pomp and circumstance. They paraded their soldiers with drums, fifes, and bagpipes, and the ambassador and his staff rode up on horseback dressed in their finery, with much cloth of gold and black sable fur in evidence. The Russian tent was floored with Turkish carpets, and a silk-and-gold Persian carpet covered the ambassador's table, upon which stood his papers, an inkstand, and a clock. The Manchus had approached the tents with equal pomp, “in all their Robes of State, which were Vests of Gold and Silk Brocade, embroider'd with Dragons of the Empire,” but upon hearing of the Russians’ regalia, the Manchus decided to use understatement to symbolize their magnificence. They removed all marks of dignity except one great silk umbrella carried before each official.31

The first negotiations between Russia and China were conducted in Latin. The Chinese had two Jesuit translators, one French, the other Portuguese. The Muscovite delegation had a Polish translator of Latin.

With the preliminary rituals completed, Muscovy and China proceeded to carve up much of northeastern Inner Eurasia. Muscovy kept Nerchinsk, but gave up Albazin and all claims on Mongolia. This consigned Mongolia to the Chinese cultural, political, and commercial sphere until the twentieth century. Moscow also promised to remain neutral in the wars between the Qing and the Oirat Zunghar Empire. Muscovite merchants were permitted to trade in China, as long as they carried passports. Symbolically, the treaty marked a shift in Chinese foreign relations, for it was the first modern Chinese treaty that seemed to concede the equality of a foreign power.32

The new treaty reoriented Muscovite trade through eastern Inner Eurasia. By the 1690s, the Oirat wars had cut the trade routes through the Kazakh steppes, Lake Yamysh, and Zungharia. A more central route, through Yeniseisk, Irkutsk, and Mongolia, may have been used as early as 1649, when Chinese goods first appeared on markets in Yeniseisk. The first large Muscovite caravan used it in 1674. After 1727 it would become the main Russian route to China. Bukharan merchants, who had traded in Siberia since the fourteenth century, set up warehouses and businesses in western Siberia and sent their own caravans along the route through Irkutsk. In 1686–1687 business along the route was so brisk that Irkutsk ran out of warehouse space.33 Between 1690 and 1730, as war flared in Mongolia, traders from Russia began to use a route even further east, through Nerchinsk and western Manchuria.

The first formal trade mission under the new treaty left Nerchinsk in December 1689. At first the trade was open to licensed private traders, but only the richest could afford the many costs and delays, as it took at least three years to travel from Moscow to Beijing and back. The main goods exchanged were Russian furs and Chinese cloths, in particular silks, cottons, and damasks. Though limited to one or two caravans a year, the trade could be profitable. By 1700, the value of traded goods amounted to 240,000 rubles, more than the entire value of the Central Asia trade.34 Some merchants continued to use the shorter route through Khuriye (Urga) in Mongolia, setting out from Irkutsk instead of Nerchinsk. Khuriye (modern Ulaanbaatar) lay at the border between the grassy northern lands of Mongolia through which horses and oxen provided transport, and the Gobi desert, where camels were the main form of transport. That made it a natural stopping point for caravans, as they switched from horses and oxen to camels, and Russian merchants were allowed to trade there from 1706.35 By the second decade of the eighteenth century, there was a glut of goods on both sides, and the caravan trade declined. One of the last great caravans set out in September 1727, with 637 wagons, 1,650 horses, 565 cattle, 205 men, and goods worth over 330,000 rubles.36 After long delays it reached Beijing, but most of its goods remained unsold. After 1762 the Russian government left the China trade to private merchants.37

In 1728, Russia negotiated a new treaty with China at Kiakhta, a Siberian town not far from Nerchinsk, and near the border with Mongolia (Figure 8.1). For the first time in the region's history, there appeared a fixed international border. The Kiakhta treaty allowed trade caravans, but also allowed trade at Kiakhta itself. The Russians and Chinese both had long experience of border markets, but the Kiakhta markets proved unusually successful, while the caravan trade to China withered.

Figure 8.1 Kiakhta today. Arkady Zarubin, https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiakhta#/media/File:Kyahta.s_gory.JPG. Used under CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/.

Kiakhta was in many ways a typical Siberian town of the period, dominated by its fortress, with a population of officials, soldiers, artisans, and traders. It also had a Chinese settlement. A German traveler described it in 1772:

It consists of a fortress, and a small suburb … There are three gates, at which guards are constantly stationed: … The principal public buildings in the fortress are a wooden church, the governor's house, the customs house, the magazine for provisions, and the guard house. It also contains a range of shops and warehouses, barracks for the garrison, and several houses belonging to the crown; the latter are generally inhabited by the principal merchants … [The Chinese town] is situated about a hundred and forty yards south of the fortress of Kiachta … Midway between this place and the Russian fortress, two posts about ten feet high are planted, in order to mark the frontier of the two empires: one is inscribed with Russian, the other with Manshur [Chinese] characters.38

The Kiakhta treaty of 1728 set up mechanisms to resolve further disputes, and these worked so well that the treaty stood until 1860, when the balance of power had shifted against China. Stable relations with the Russian Empire gave the Qing the freedom to impose their authority over their own borderlands, and gave Russia the time it needed to consolidate its grip on Siberia.

MONGOLIA: QING HEGEMONY AND THE DEFEAT OF THE ZUNGHAR EMPIRE

The first negotiations between Russia and China took place during the huge wars between the Qing and the last great steppe empire, that of the Oirat Zunghars. Ending as they did with the destruction of the Oirat, and the empire they had created, the Zunghar wars count as a major turning point in the history of Inner Eurasia.

Mongolian history in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries was shaped primarily by the Zunghar wars, the rise of the Qing dynasty in China, and the spread of Buddhism within Mongolia.

EASTERN MONGOLIA AND THE RISE OF THE QING

The Qing dynasty came from the Manchurian borderlands of northeastern China, which explains why they understood the steppe world much better than the Ming. Indeed, in some ways the Qing can be counted as one more of the China's northern dynasties, along with the Yuan. That may be why they devoted huge resources to the task of managing and eventually dominating the Mongolian steppes.

The founder of the Qing dynasty was a Jurchen leader, Nurhachi (b. 1559, r. 1616–1626), from the Manchurian borderlands. This was a region of farmers and pastoralists, with many ties to Mongolia. From the 1630s, many Khalkha Mongol leaders would support the Qing, first as military allies, but eventually as overlords and protectors of the Khalkha, particularly as the military threat grew from the rising Zunghar empire in western Mongolia. The Qing reinforced a sense of shared heritage through marriage alliances with Khalkha leaders, and cultural borrowings, including the Mongol script.

In 1636, Nurhachi's son Huang Taiji proclaimed himself emperor, renamed his dynasty the Qing (or “pure”), and accepted the submission of most Inner Mongolian leaders.39 Like his father, Huang Taiji (r. 1627–1643) regarded himself as the heir of the Yuan dynasty, which implicitly gave the Mongols high status in the new empire. But the Qing would rapidly become Sinicized, and Mongolia would once again begin to look like a Chinese colony. In 1644, under Emperor Shunzhi (1643–1661), the Qing entered China and took Beijing as their capital. Nurhachi's great grandson, Kangxi, would rule China for 60 years, from 1661–1722, and the Qing dynasty would survive until 1911.

Any possibility of building an independent Mongolian Empire had probably vanished after the death, in 1634, of Ligdan Khan (b. 1588, r. 1604–1634) of the Chahar Mongols. Ligdan Khan was the last of the true Chinggisids, and the last representative of the Yuan dynasty. With his death, and the capture of his sons by Emperor Huang Taiji, the eastern Mongols lost a powerful unifying focus, and never again would Chinggisid lineage prove the key to political power in Mongolia. Two years after his death, the Qing began dividing Khalkha Mongolia into “banners” (koshuu, a term similar in its original usage to the older tumen, a military formation). Each banner was headed by a local hereditary prince or “ruling lord” (Zasag noyon), or by a local lamasery, and was supposed to provide about 7,500 soldiers. Banners, like the military units favored by Chinggis Khan, were military rather than tribal units, so they cut across the military authority of traditional leaders. But they were also territorial units, so they shut off traditional migration routes, which further limited the power of local leaders. Nevertheless, lamaseries and local princes remained the dominant forces in the lives of most Mongolians, as they owned large numbers of serfs, controlled traditional migration routes, and employed commoners to herd their livestock.40

In 1640, six years after Ligdan's death, and in the shadows of a rising Qing dynasty, there was one last attempt to revive pan-Mongolian solidarity at a quriltai held in Tarbagatai, in Zungharia. This was attended by 44 Mongolian leaders from both the Khalkha federations of the east and the Oirat in the west. The quriltai adopted a common legal code and agreed to adopt Buddhism, in its reformed “Yellow Hat” or dGe-lugs-pa form, as the religion of all Mongols.41 The quriltai also agreed to punish any Mongols who attacked other Mongols. But it could not establish a single supreme ruler, and failed spectacularly to prevent further conflicts.

In the absence of a single political and military leader, religious figures played an increasingly important role in Mongolian politics, as they did in Central Asia and Xinjiang. Even Ligdan Khan had based his political and military ambitions as much on Buddhism as on his Chinggisid genealogy, and he had been a great patron of Mongolian Buddhist scholarship.42 In 1639, several Khalkha leaders accepted Zanabazar (1635–1723), the son of the Tushetu khan, as a living Buddha (or Khutugtu), and as the religious leader of all the Khalkha Mongols.43 Only 4 at the time of his election, Zanabazar was sent to Tibet to study under the 5th Dalai Lama (1617–1682), the leader of the Yellow Hat school of Buddhism. Zanabazar came to be known as the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu, from the Tibetan for “Reverend Noble One.” Because of his height, he was also known as Öndör Gegeen or “Tall Majesty.” After returning to Mongolia, Zanabazar built a lamasery in 1680, around which would grow the settlement of Khuriye (modern Ulaanbaatar). The high prestige of the new office of Jebtsundamba Khutugtu owed much to Zanabazar's talents as a painter, a sculptor, a writer, and translator of religious texts. He also invented a new Khalkha script, the Soyombo script. Zanabazar lived for long periods near Erdeni Zuu lamasery in former Karakorum, where he built a forge and produced sculptures of remarkable beauty. His work was part of a larger flowering of Buddhist scholarship and art that followed the second conversion to Buddhism from the late sixteenth century.

Zanabazar held the office of Jebtsundamba Khutugtu until his death in 1723, and the office itself would survive for another two centuries, until 1924. The Jebtsundamba Khutugtus (often known by the Mongols as “Öndör Gegeen”) enjoyed both religious and political authority among most eastern Mongolian tribes, as Zanabazar was, technically, a Chinggisid. Over time, the Jebtsundamba Khutugtus acquired a status in Mongolia similar to that of the Dalai Lama in Tibet. They also acquired great wealth through grants of serfs.44

But Zanabazar was incapable of overcoming the political divisions that left the Khalkha vulnerable to both the Qing and the Oirat. In the 1670s and 1680s, power in Khalkha Mongolia was disputed between the western Zasagtu khan and the eastern Tushiyetu khan. When the Oirat leader Galdan, ruler of the rising Zunghar Empire, lent his support to the Zasagtu khan, the Tushiyetu khan killed both the Zasagtu khan and Galdan's brother. This act provoked a massive Oirat invasion of eastern Mongolia in 1688, which drove most Khalkha leaders, including the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu, into Inner Mongolia. Here, after an appeal from the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu, Kangxi agreed to protect the Khalkha leaders and their followers.45 Khalkha leaders now faced the same dilemmas as Bohdan Khmelnitskii at the western end of Inner Eurasia, and debated whether to seek Muscovite or Chinese aid against the Oirat. But cultural links to the Qing and the closeness of Qing power decided the issue. As the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu put it, “the Manchus have the same kind of religion and wear the same clothing as the Mongols. However, the Russians have a different kind of religion. Therefore, it would be a good idea for us to submit to the Manchus.”46

In 1691, after Qing armies had repelled Galdan's invasion, most Khalkha leaders accepted Chinese suzerainty at the Convention of Dolonnor (modern Duolun) in Inner Mongolia. The gathering was summoned by Emperor Kangxi and attended by 550 Khalkha nobles, as well as by the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu, Zanabazar.47 Zanabazar lived in Beijing until 1701, where he became a close friend of the emperor, Kangxi. He eventually returned to Mongolia and supervised the rebuilding of the Erdeni Zuu lamasery.

The 1691 treaty of Dolonnor marks a fundamental turning point in the political history of eastern Mongolia. The submission of so many regional khans to the Qing left the spiritual authority of the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu as the only unifying force in Khalkha Mongolia.48

WESTERN MONGOLIA AND THE RISE AND FALL OF THE ZUNGHAR EMPIRE

As the Khalkha fell into the Qing orbit, the Oirat Mongols, whose lands were remote from both the Qing and Muscovite empires, built Inner Eurasia's last great steppeland empire.49

In the fifteenth century, under Esen, the Oirat had been, briefly, a major international power. But in the sixteenth century they were divided and weak, though they continued to be active along the Silk Roads, and in the trading cities of Xinjiang, from Turfan to Kashgar.50 Oirat leaders granted licenses to caravans of “Bukharan” traders traveling through the Tarim basin and Zungharia, and controlled the trade in satins and tea. Particularly important was their control of the oasis of Hami, “the door, opening and closing access to China.”51 The Oirats also benefited from the creation of a new, Siberian branch of the Silk Roads in the early seventeenth century. Whether driven by warmer steppeland climates or expanding commercial opportunities, Oirat populations increased in the early seventeenth century, and agriculture spread in Zungharia. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, demographic and military pressure from the Khalkha Mongols under Altan Khan, and the Kazakh under Taulkel Khan (r. 1586–1598), drove Oirat leaders to seek new pasturelands and new opportunities to the north and west, where Muscovite expansion into Siberia was creating new markets. Eventually, these pressures would drive two major migrations out of the Oirat lands, one to the Volga region in 1630, and a second, under a group known as the Khoshut, to Tibet in 1635–1637. (The first, or Kalmyk, migration is described later in this chapter.)

Population growth played an important role in the rise of a new Oirat Empire with its heartland in Zungharia. Several major Oirat leaders came from the relatively agrarian and urbanized Ili valley region, formerly the heartland of Qaidu's empire, for this area, though dominated by pastoralists, allowed some intensification as it contained farming regions and towns. An early seventeenth-century Oirat leader, Kharakula (d. 1634), conquered much of western Mongolia, encouraged agriculture, built a capital, and invited foreign craftsmen, including Russians. His son, Erdeni Baatur Khung-Taiji (r. 1635–1653), established a unified Zunghar federation from the mid-1630s. The nineteenth-century Russian Sinologist Bichurin described Erdeni Baatur Khung-Taiji as the Oirat Peter the Great. He encouraged agriculture and urbanization.52 In his time, and as the result of trade agreements with Muscovy, the salt-trading city of Lake Yamysh became one of the largest cities in Inner Eurasia.53 He was also interested in cultural modernization. Under Khung-Taiji, many Oirat leaders adopted Tibetan Buddhism, a process aided by the fact that in 1640, at the time of the last pan-Mongolian quriltai in Tarbagatai, a Khoshut Oirat leader, Gushi, had become effective ruler of Tibet. Another Khoshut, Zaya Pandita (1599–1662), created an Oirat script. With his disciples, he translated much Buddhist writing into the new written language.

In 1643, Oirat armies inflicted a devastating defeat on the Kazakhs. In 1647 Erdeni Khung-Taiji negotiated a border treaty with Muscovy, dividing the Siberian tribute between the two expanding empires. (See above, p. 180.) Once again, the Oirat were becoming a significant regional power.

Khung-Taiji's second son, Galdan Boshugtu Khan (b. 1644, r. 1678–1697), was sent to study in Tibet. He returned to become the Oirat leader in 1678, with the support of the Dalai Lama. In 1678–1680, he conquered the Tarim basin and much of Zungharia. This gave him a rich revenue base and control over the trade routes between China and Central Asia. Though none of the Zunghar leaders were Chinggisids, in 1682 the Dalai Lama granted Galdan the title of “Boshugtu Khan,” or khan by divine grace, which effectively licensed him to use the title of khan.54

Like his father, Erdeni Khung-Taiji, Galdan was a modernizer. He encouraged farming and urbanization, particularly around Khulja, on the Ili river. He incorporated cannon into his armies by mounting them on camels. He supported mining for metals, and encouraged the production of gunpowder. Indeed, his interest in Xinjiang and Central Asia was motivated in part by the need for saltpeter. He minted coins and printed books in the newly invented Oirat script.55 Like his predecessors, Galdan found that from Zungharia he could control the major trade routes from China to Central Asia and Muscovy.

Eventually, though, conflicts over trade created friction with both Muscovy and China. At the beginning of his reign, Galdan sent an official embassy to China, the first from the Oirats for two centuries.56 The Qing reluctantly allowed it to trade. But, as had happened so many times before, the trade missions grew in size as more and more traders and Oirat leaders sought a share in their profits. Qing officials became increasingly unhappy. In southern Siberia, Galdan clashed with Muscovy, and in the 1680s he secured control of the trade routes and major trading towns of southern Kazakhstan, which gave him a choke hold on the fur roads between Central Asia and Siberia.

In 1688, Galdan invaded eastern Mongolia, to avenge the murder of his brother and his ally, the Zasagtu khan. (See above, p. 185.) He captured the monastery of Erdeni Zuu, the effective capital of the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu, Zanabazar, and one of the largest permanent settlements in the Khalkha lands. As we have seen, his victories eventually drove most Khalkha leaders into the arms of the Qing, at the 1691 Convention of Dolonnor. The Qing finally turned on Galdan after signing the treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, which ensured Muscovite neutrality in any wars with the Oirat.

The Qing rejected Galdan's demand that they punish the Tushetu khan for killing Galdan's brother, and began to cut back Oirat trade missions. The restrictions on trade were galling and dangerous for Galdan, whose followers resented their exclusion from the China trade.57 That Galdan faced serious internal problems is shown by the defection of several Zunghar leaders, including Galdan's nephew, Tsewang Rabtan, in 1689. These splits point to one of the empire's basic weaknesses, the lack of a clear ruling lineage. Unlike Chinggis Khan, Galdan and his successors faced regular challenges from rival clans and tribes.58

As splits emerged within the Oirat leadership, the Qing emperor, Kangxi, decided on a massive mobilizational effort to crush the Zunghar Empire. Qing and Oirat armies fought an indecisive battle at Ulan Butung in 1690. But the next year, most eastern Mongol leaders accepted Qing suzerainty at Dolonnor. The Qing could now pursue the Oirat without worrying about uprisings in eastern Mongolia. In 1695, famine forced Galdan to move eastwards from the Khobdo region, probably with no more than 20,000 troops. This time, Kangxi himself led a vast army of perhaps 400,000 into Mongolia. In May 1696, at the Terelzh river near Khuriye, Kangxi's army defeated Galdan, whose forces now numbered no more than 10,000.59

The vast scale of the Qing mobilization and the huge difference in the size of the armies undoubtedly affected the outcome, but so did Chinese use of cannon, built with the help of Jesuit missionaries. But Galdan's defeat was also due to internal conflicts, as his army was demoralized and weakened by the attacks of his nephew, Tsewang Rabtan.60 Nevertheless, moving the vast Qing army through Mongolia was costly and risky, and despite all its advantages, the Qing armies could easily have lost the battle at the Terelzh river.61 If they had, lack of supplies would soon have forced them to retreat.

After his defeat in 1696, Galdan and some 5,000 followers headed west. In September, a refugee from this pathetic army reported that “Galdan was now extremely impoverished and short of supplies, that he not only lacked food, yurts and tents, but even somewhere to go, as he was surrounded on all sides. Now, he feeds himself on roots.”62 Famine drove soldiers to desert, and by November, Galdan had only 100 men. He died in March 1697. His opponents claimed he took poison, depriving Kangxi of the chance to publicly humiliate and execute him.63

Despite the rout of Galdan, the Zunghar Empire, protected as it was by distance, would survive for another half century. It reformed under Galdan's nephew and successor, Tsewang Rabtan (1697–1727). At first, Tsewang was conciliatory towards the Qing. He surrendered Galdan's ashes in 1698, and handed over Galdan's daughter the next year. He had little choice. His empire was impoverished by war and squeezed on three sides by Russia, the Kazakhs, and the Chinese. But soon, like his predecessors, Tsewang began to rebuild and diversify the economy, by encouraging agriculture, industry, and trade. A Russian report of 1734 noted the results a generation later.64 Grain of all kinds was widely grown, and now not just by Muslim captives but also by Zunghars. The Oirat had lots of salt to sell and produced fine vegetables. They exploited their control of the east–west trade routes by selling tea and silks westward, or importing brick tea and cloths that could be sold in Zungharia itself. Large trade missions, often headed by Central Asian (or “Bukharan”) merchants, traveled regularly to China and Tibet.

Like his contemporary, Peter the Great, Tsewang encouraged industrialization by creating iron and weapon manufactures using foreign (including Russian) experts. He also set up leather-processing and cotton cloth-making enterprises. Many of these factories probably depended, like those of Peter the Great, on forced labor. Farmers were moved from the Tarim basin to the region around modern Urumqi, and each year several hundred women were sent to Tsewang's settlement in the Ili valley to sew uniforms for the army. In 1731 the Russian envoy, Ugrimov, met a Swede, Renat, who had been captured at the battle of Poltava and exiled to Siberia. In 1716 he was captured by the Oirat as a member of Buchholtz's expedition to Lake Yamysh, after which he was charged with the production of cannons, powder, and mortars.65 With Renat's help, the Zunghars even printed books and produced the first modern maps of the region. According to Perdue, the Zunghar maps were more accurate and detailed than anything available to the Russians or Chinese in the eighteenth century.66 Renat would eventually return to Sweden.

Tsewang, like Peter the Great, tried to build up industry to produce arms and uniforms for the army, and luxury goods for the Oirat ruling elite.67 He rebuilt his military power from a base near Khulja in the Ili valley. In 1698, just a year after Galdan's death, Tsewang launched devastating attacks on the Kazakhs. Twenty-five years later, in 1723, he launched new attacks that would permanently weaken the Kazakh Great Horde.68 Conflicts in the Tarim basin between Ishaqiyya and Afaqiyya branches of the Naqshbandiyya prompted Tsewang to invade southern Xinjiang in 1713, to take hostages from ruling families, and exact tributes from the region's cities. Each year, Zunghar military units arrived in the Tarim cities to exact tributes, including large amounts of silver and grain from Kashgar, and smaller levies on goods such as cotton and saffron, as well as labor services including milling and transportation.69

Competition for Siberian tributes irritated relations with the Russian Empire, but both sides benefited from increased trade between Zungharia and Siberia, and they avoided outright war. In 1717 Tsewang turned east and overran the Koko Nor region in support of the Dalai Lama, after which he seized control of Tibet. However, in 1720, Qing armies expelled the Zunghars from Tibet. From 1728 until near the end of the nineteenth century, Tibet became, in effect, a colony of the Qing Empire. This indecisive conflict, though fought mostly in Zunghar lands (Qing armies captured Hami and Turfan), was immensely costly for China, and created discontent in Khalkha Mongolia, whose populations paid for much of the Qing mobilizational effort. It also raised the prestige of the Zunghar armies. John Bell, a Scot in the service of the Russians, described a battle between the Qing and the Oirat in 1718. (See also Figure 8.2.) It illustrates the difficulties Qing armies faced at the end of lengthy supply lines:

Figure 8.2 Giovanni Castiglione, War Against the Oirat. Reproduced from Golden, Central Asia in World History.

the Chinese, being obliged to undertake a long and difficult march, through a desert and barren country, lying westward of the long wall; being also encumbered with artillery, and heavy carriages, containing provisions for the whole army during their march; had their force greatly diminished before they reached the enemy. The Kontaysha [Tsewang Rabtan], on the other hand, having intelligence of the great army coming against him, waited patiently on his own frontiers, till the enemy was within a few days march of his camp, when he sent out detachments of light horse to set fire to the grass, and lay waste the country. He also distracted them, day and night, with repeated alarms, which together with want of provisions, obliged them to retire with considerable loss.70

As we have seen, the essential problem for all agrarian armies in the steppes was to protect infantry armies that needed significant supplies of food and water, unlike their opponents who, as Bell pointed out, “having always many spare horses to kill and eat, are at no loss for provisions.”71 Any solution depended on gaining a massive material superiority over their steppe opponents. It was necessary to devote large forces to the protection of supply trains, and, eventually, to build fortified storage areas. Since the Han era, no Chinese army managed to spend more than about three months in the steppelands, and Kangxi's armies faced the same limitations. The Qing managed to defeat the Oirat only after overcoming this limitation by building new supply lines deep into the steppes.72

Meanwhile, war also took its toll on the Zunghars. In 1732, Ugrimov reported that most of the men had been taken to the wars.73 In 1731, Tsewang's successor, Galdan Tsereng (r. 1727–1745), defeated a Qing army. But in 1738, he negotiated a truce under which the Zunghar agreed to remain west of the Altai. There followed more than 15 years of peace early in the reign of the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736–1795). Zunghar attacks on the Kazakhs drove them into the arms of the Russians, as earlier Zunghar attacks had driven the eastern Mongols to seek Chinese protection. In 1731, for the first time ever, Kazakh khans formally sought Russian protection.

After the death of Galdan Tsereng in 1745, conflicts over the succession encouraged one contender, Amursana, to flee to the Qing in 1754. The emperor, Qianlong, seized on these divisions to finally crush the Zunghars. He assembled an army of perhaps 200,000, including many Mongols, in western Khalkha. In the spring of 1755, with Amursana in command of part of the army, Qing forces advanced into Zungharia as far as the Ili valley, meeting no resistance on the way. The Oirat leader Davatsii was eventually captured in Kashgar.74 This was the end of the Zunghar Empire. The Chinese army distributed leaflets promising peace if Zunghars accepted that they were now Chinese citizens. Qianlong demobilized his huge and expensive army for fear of provoking new uprisings, and prepared for a meeting at Dolonnor at which he expected the Zunghar leaders to swear loyalty as the Khalkha leaders had done 60 years earlier.75

Instead, in late 1755, Amursana turned on the Chinese, slaughtered a Chinese contingent in Khulja, and began to form a new Zunghar army. Qianlong assembled a new and even larger army of some 400,000, which marched through Mongolia and into Zungharia in 1756. There was a brief uprising in Mongolia, provoked by the cost of supporting this colossal army, but Amursana failed to join it, or to create a united Zunghar army. Eventually, he fled to Russian Siberia, where he died in Tobolsk of smallpox.76

No effective Zunghar opposition remained, and the Chinese army began to exterminate the population of Zungharia. Zlatkin writes that, of a population of some 600,000 people, only 30,000–40,000 survived, and only because they fled to Russian territory; while other estimates suggest that a million Oirat may have died.77 The genocide was systematically aimed at young men. One commander who had captured a group of Oirat was told by the emperor to “take the young and strong and massacre them,” and hand over the women as booty.78 According to a Chinese source, 40 percent of 600,000 Zunghars died of smallpox, 20 percent fled to the Russians and Kazakhs, and 30 percent were killed by the army. So great were the losses in Zungharia that Qing officials began to plan ways of repopulating the region by settling Han peasants, Manchu bannermen, and Chinese Muslims, or Hui.79 Those who fled to Russia were sent to the Kalmyk lands on the Volga if they acknowledged Christianity, but returned to Zungharia if they refused. There they faced Kazakh harassment, and many were captured and sold as slaves in Siberia.

By 1758 the conquest of Zungharia was complete. Mopping up operations drew Qing armies into the Tarim basin cities the following year, while some Qing contingents reached Talas for the first time in 1,000 years, as well as Kokand and Tashkent.80

In the history of the last great pastoralist empire, we see several determined and skillful efforts to build a new mobilizational machine from a base in the steppes, while using many of the skills and resources of the agrarian lands and introducing modern industries. However, the military base of the empire was still the traditional smychka, and the Oirat failed because they could not mobilize sufficient human or material resources in a world in which populations, productivity, and military power were growing in neighboring agrarian lands, and its own territory was being squeezed on all sides. Nor did any of the leaders show the political skills needed to hold together a grand Oirat coalition. The Qing benefited both from their superiority in numbers and resources, and from divisions within the Oirat leadership.

The Zunghar Empire survived as long as it did largely because it was so far from China and Muscovy. That is also why defeating it required an exceptional mobilizational effort on behalf of the most populous state in the world. So vast was the mobilization that, for the first time ever, it allowed Chinese armies to spend more than a hundred days in the steppes.81 The mobilizational achievement depended partly on the growing commercialization of the Chinese economy, which allowed the government to purchase grain over large areas without imposing excessive burdens on the peasantry of the northwestern provinces.82

As Perdue argues, the crushing of the Zunghar counts as a fundamental turning point in world history, for it marks the end of the pastoralist empires that had shaped Eurasian history for two millennia.83 Defeat of the Zunghars also marks the rise of Chinese control over what would eventually become Xinjiang. The region was now more closely controlled by China than it had ever been under the Han, the Tang, or the Yuan. With control of both Mongolia and Xinjiang, China became once again a major Inner Eurasian power.84

There is a curious global coda to the history of the Zunghar Empire. Pekka Hamalainen has shown that, just as Inner Eurasia's last pastoralist empire was being crushed, North America's first pastoralist empire was being constructed by the Comanche, using horses imported to the Americas by the Spanish.85 The Comanche Empire, too, was based on a sort of smychka that allowed highly mobile cavalry armies to generate great wealth from neighboring regions through a complex combination of trade, slave raiding, farming, and tribute exaction. The Comanche Empire survived for a century, well into the nineteenth century until it, too, was smothered by an emerging agrarian superpower, the USA.

CENTRAL INNER EURASIA: THE URALS AND THE KAZAKH STEPPES

Muscovite expansion into the Urals and the Kazakh steppes was a much slower process than the conquest of Siberia, but it began in the seventeenth century. This section surveys Muscovite relations with the Kalmyk, the Bashkir, and the Kazakh.

THE KALMYK

Early in the seventeenth century, as the Qing and Romanov dynasties consolidated their power, the politics of the Volga region was transformed by the arrival of the Kalmyk (Turkish for “Oirat”) in the steppes north of the Caspian Sea.86

As demographic, military and political pressure increased on the pasturelands of western Mongolia, regional leaders had to plan for an uncertain future. Trade was one option available to them, but another, familiar to anyone who had joined a raiding party, was to take over the pasturelands of other, weaker, groups of nomads. In 1608, a large raiding party of Khoshut Oirats moved deep into the Nogai steppes north of the Caspian Sea, where they found promising new pasturelands. In 1630–1632, a Torghut leader, Qo Orlog, who had earlier tried to negotiate trade relations with Muscovite officials in Siberia, led a much larger invasion into the Nogai steppes.87 After a well-planned but difficult migration, in which they fought their way through the territory of several groups of Kazakhs, he and his followers settled north of the Caspian Sea. Here, they displaced local Nogai tribes and began to nomadize on the eastern shores of the Volga. This dangerous migration into already occupied steppelands illustrates the increasing claustrophobia of the steppelands, as well as the growing military power of the Oirat. Oirat groups would continue to arrive in the Caspian steppes in the seventeenth century. There were particularly large migrations in the late 1670s and 1680s.

The Nogai had nomadized in the Caspian steppes for over a century, since the Muscovite conquest of Astrakhan in 1556.88 The Kalmyk drove them west into the Caucasus steppes, where they became dependents and allies of the Crimean khans. The Kalmyk, once established on the Caspian steppe, built an effective new smychka, based mainly on the exploitation of looting zones. They raided widely, sometimes into Muscovite territory, but more often towards Khiva or the Caspian or Pontic steppes.

The Kalmyk so disrupted trade between Central Asia and the Black Sea region that Moscow received appeals from Bukhara, Khiva, and Balkh to form an anti-Kalmyk alliance. In the 1620s, the Kalmyk seized pasturelands on either side of the southern Volga in the former heartlands of the Golden Horde. From here, they looted the lower Volga area and northwards into Bashkiria in the Urals, and even into southern Siberia. Their first serious defeat came in 1644, when a Kalmyk army was trapped in the mountains of the north Caucasus and largely destroyed, along with its leader or tayishi, Qo Orlog. The Kalmyk snubbed Muscovy's first attempts at negotiation in 1648, claiming that they occupied Nogai lands by right of conquest. In 1651 the Kalmyk inflicted a massive defeat on Crimean and Nogai forces.

In 1655, the Kalmyk leaders signed a treaty or shert’ with Moscow, a symbolic act made more palatable for the Kalmyk by treating the Tsar of Muscovy as the legitimate successor of Jochi, and therefore a Chinggisid. For Moscow, alliances with the Kalmyk and the Don Cossacks were attractive, because they offered dangerous cavalry allies for the wars with Poland and Turkey that were inevitable after Moscow's entry into Ukraine in 1654. But managing these new alliances would prove a complex task, with endless possibilities for misunderstanding, deceit, and conflict. The Russian translation of the 1655 shert’ implied Kalmyk subordination, though documents signed along with the treaty allowed the Kalmyk to interpret it as an alliance of equals. Moscow granted the Kalmyk use of pasturelands along the Volga, ordered Muscovite and Bashkir forces not to attack the Kalmyk, and allowed the Kalmyk to trade in the towns of the southern Volga. In 1657 Crimea offered the Kalmyk an alliance, after which Moscow improved its terms, sending the leading Kalmyk tayishis rich gifts, permission to use more pasturelands, and the right to trade duty-free in nearby towns. In 1660 Muscovy signed a new treaty with the Kalmyk, sweetened with gifts, but including the demand that the Kalmyk submit hostages. “Step by step,” writes Khodarkovsky, “the Kalmyks were embarking on a slippery road that would inevitably lead to their growing dependence on Moscow.”89

In 1664, Moscow sent symbols of office to a new chief tayishi, including a gilded silver mace. The symbolism clearly implied that the Tsar had the right to confirm the Kalmyk ruler in office, just as Moscow had assumed the right to appoint Cossack atamans. In 1669, a new tayishi, Ayuka, signed new treaties. These contained further restrictions, including permission to trade only in Astrakhan and Moscow, and bans on diplomatic contacts with Muscovy's enemies. Kalmyk power was at its height during Ayuka's long reign, from 1670–1724. In the first quarter of the eighteenth century, the Kalmyk counted as a major military power and received delegations from Russia, the Ottoman Empire, and even Qing China.90

Eventually, though, Kalmyk power would be undermined by the same slow advance of fortified lines that would tame their Kazakh and Bashkir neighbors. Under Peter I, Muscovy began to build new fortified lines in the Volga, Bashkir, and Kazakh steppes. These limited the freedom of movement of Kalmyk armies and, like a vast guliai-gorod, they also provided protection for a slow advance by Russian settlers. The Tsaritsyn line, completed in 1718, linked the Don to the Volga, cutting off migration and trade routes from the Caucasus to the north. The Russian government controlled trade through these lines, only allowing registered merchants to trade with the Kalmyk. In the background, under the partial protection of the new fortified lines, settlers encroached on what had once been Kalmyk pasturelands, coming from Don Cossack villages, from fishing villages along the Volga, and even, later in the eighteenth century, from German immigrants.91

After the 1720s, the unity and power of the Kalmyk declined precipitously as Russian settlers and forts closed in on their pasturelands. Impoverished Kalmyk began to seek work in Russian towns or manufactures. In 1771, most of the remaining Kalmyk – about 150,000 people or 31,000 households – took the desperate gamble of heading back east on the promise of a Qing welcome in Zungharia, which was now depopulated after the defeat of the Zunghar Empire. Once again, the Kalmyk embarked on a terrifying long march through the territory of their old enemies, the Kazakh. Only a third survived. About 11,000 households had stayed behind in Kalmykia, and when these, too, attempted to emigrate, the Russian authorities persuaded them to stay by offering lavish gifts. The remaining Kalmyk became integrated more fully within the Russian administrative system and large areas of Kalmyk pasturelands were opened to peasant settlers.

THE 1730s: THE CONQUEST OF BASHKIRIA AND THE URALS

In the 1730s, the Russian Empire established its control over the Urals region, with its valuable agricultural lands, its furs, and its mineral wealth.

The Bashkir were a diverse group of mainly Turkic-speaking peoples, who had adopted steppe forms of Islam in the fourteenth century and lived on both sides of the Urals mountains. They included pastoralists in the south, and forest peoples in the north, many of whom spoke Finno-Ugric languages, and depended on hunting, the taking of furs, and fishing and beekeeping. In the seventeenth century, the Bashkir occupied a much larger region than today's Bashkir autonomous republic, whose capital is Ufa. Much of their land had fallen within the Kazan khanate, and then the Siberian khanate, between the Volga, Yaik (Ural after 1775), and Tobol rivers.

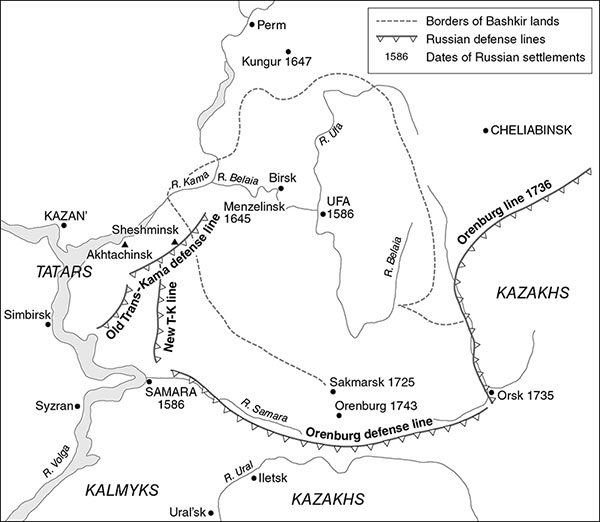

The conquest of Bashkir territory transformed Russian relations with all peoples east of the Volga. The key change was the decision in the 1730s to build a new line of forts running east from the Volga, around the southern end of the Urals, and up into the Kazakh steppes and southern Siberia. This was the so-called Orenburg line (Map 8.2). Ivan Kirilov, the official who masterminded these schemes, argued for a more active imperialism in the steppes. He compared Russian penetration of Central Asia to Spanish conquest of the Americas, arguing that if Russia did not act others might conquer the region first. Bashkir territory also yielded large amounts of furs, and included important routes to Siberia and major iron and copper manufacturies. By 1762, Bashkiria contained over 50 iron smelters and mills and almost 50 copper smelters and produced 70 percent of the empire's iron and 90 percent of its copper.92

Map 8.2 Russian expansion in Bashkiria and the Kazakh steppes, eighteenth century. Rywkin, Russian Colonial Expansion to 1917, 188.

Muscovy had started building forts on Bashkir territory soon after the conquest of Kazan’. Most were paid for by imposing onerous tributes on the local population. A governor of Ufa warned in the seventeenth century that over-zealous tribute collectors had seized horses and beaver pelts from local communities, and taken women and children as hostages, which threatened to drive away tribute-paying communities.93 Even more damaging was the influx of settlers that followed the building of Russian forts. Early in the seventeenth century, Moscow ordered a governor of Ufa to keep peasant migrants out of Bashkir lands:

these migrant Russian, Tatars, Chjuvashes, Cheremises, and Votiaks settled in many villages in their [the Bashkirs’] ancient territory. They ploughed the fields and cut the hay, cut down much of the forest including good bee trees … and because of the great number of people in their territory, the wild animals … have fled and the beaver have been wasted. They have begun to kill the animals and catch the fish and there is no place for the horse herds and cattle.94

A rebellion broke out in 1705, when the Bashkir chose an ambitious new khan, Sultan Murat. In 1708 Bashkir armies approached Kazan’. But the Bashkir suffered from both political and military divisions and their armies were soon crushed. With weak traditions of leadership, their soldiers fought with little cohesion. They normally fought on horseback, using bows, arrows, and sabers, and Russian units learnt to attack them after winter when their horses were poorly fed.95

To secure control of the Urals region, Russia planned new forts, mainly at strategic river crossings which acted as natural borders between different peoples. Forts at such points provided diplomatic bases for gift-giving and negotiations with local chiefs, and also staging points for punitive raids. The planned Orenburg line of forts was intended to cut the Bashkirs off from the Caspian and Kazakh steppe, while earlier lines had already cut them off from Kazan’. In 1734, the Empress Anna dispatched to Ufa a large expeditionary force, the “Orenburg Expedition,” led by Ivan Kirilov. Its composition reflected the growing influence of Enlightenment-era thinking in Russia. It included, as well as soldiers, “a geologist, a pharmacist, a botanist, a historiographer, an artist, several office clerks, a surgeon, a priest, several students from the Greek–Latin–Slavonic Academy, and a number of army officers.”96 In August, Kirilov laid the foundations for the new fortified town of Orenburg (called Orsk after 1743, when Orenburg was moved further west on the Ural river), at the junction of the Ural and Or rivers.

Bashkir leaders understood all too well the real significance of the Orenburg Expedition. In August 1734, they nearly destroyed a Russian detachment, prompting the dispatch of a much larger military force, and igniting a brutal five-year war in which Bashkir soldiers fought on both sides. Russian forces massacred the inhabitants of several Bashkir villages. But fort-building proceeded rapidly in 1735 and 1736, slowly tipping the military balance of power. By 1738 most Bashkir had submitted. A new uprising in 1740 prompted even more vicious retaliation. Urusov, the Russian commander, claimed that by September 1740, 1,702 Bashkir had been killed or had fled, 432 had been executed, 1,862 had been sent to Russia as serfs, 301 had been knouted and had their noses cut off, while 107 villages had been burned and lots of livestock had been seized. The new Russian governor estimated that 30,000 Bashkir had died out of a population of about 100,000. The real toll was probably much higher, magnified by deaths from starvation, disease, and cold.97

By the middle of the eighteenth century, Russia had completed a further line of forts extending southwards from the Urals to the Caspian Sea. This cut migratory routes through the “Ural gates” that had been used by pastoralists for several millennia.98 Russia now abandoned its more northerly line of forts in the Urals, having moved its military frontier some 500 kilometers south in just a few years.

THE KAZAKH STEPPES

Like the Chinese, Russia managed relations with nomadic peoples through trade as well as war. While Muscovite forces were crushing the Bashkir, trade boomed at Russia's new forts on the edge of the Kazakh steppes. Russia allowed both the Kazakh and the Kalmyk to trade without paying the customs duties demanded from Russian and foreign merchants. Forts and Kazakh protection provided enough security to attract merchants from as far afield as Kashgar, Bukhara, and Khiva to trade at new towns such as Orsk, Orenburg, and Semipalatinsk. Later in the century, Orenburg overtook Astrakhan as the largest entrepot for trade in and beyond the western Kazakh steppes.99

Huge caravans of 500 or more camels loaded with merchandise and silver traversed the Kazakh steppe between Orenburg, Khiva, and Bukhara. The safe passage of these caravans depended on their protection by local Kazakh and Kalakalpak leaders, some of whom exacted a safe passage fee, while others preferred to rely on presents and access to Russian markets as a reward.100

These profitable trades gave Russian officials great influence in the steppes.

While most of the populations of the three Kazakh hordes nomadized, their khans, like the khans of Crimea, were more urbanized, and often resided in the commercial cities of the Syr Darya. In the early eighteenth century, the Lesser Horde used pastures north-east of the Caspian Sea, along the Emba and Yaik rivers. It could field about 30,000 warriors. The Middle Horde, which occupied the central and northern Kazakh steppes, could field about 20,000 warriors. And the Greater Horde, whose lands in Semirechie bordered on Oirat lands in Zungharia, could field about 50,000. In 1691, Oirat envoys told the governor of eastern Siberia in Irkutsk that the Kazakh controlled 11 major towns including Turkestan (formerly Yasi), which was the residence of the khan of the Greater Horde throughout the seventeenth century.101

As Russian, Kalmyk, and Oirat pressure increased, trade became increasingly important for Kazakh leaders. Caravans traveled through the steppes from Central Asia to the Urals, Kazan’, and Russia, to the fortified cities of southern Siberia, and eastwards through Semirechie, Zungharia, and Kansu to China. The Siberian caravans were particularly important after the Kalmyk migrations of the early seventeenth century cut traditional caravan routes to Central Asia through Astrakhan. Eventually, after an expedition into the eastern Kazakh steppes led by Buchholtz in 1716, Russia began building a new line of forts from Omsk (1716), along the Irtysh river, to Semipalatinsk (modern Semey), whose fort was completed in 1718. By the middle of the eighteenth century, this line, and the line of Urals forts running south from Uralsk to the Caspian Sea, had woven a noose around the entire Kazakh steppe. (See Map 11.1 for the line of forts.)

As the Russian presence in Siberia grew, trade with Bukhara began to flow through the southern Siberian towns of Tobolsk and Tara. The Kazakh benefited from these trades, as all caravans through the Kazakh steppes had to pay for protection. This is why Peter described the Kazakh as “the key and the gates to all of Asia.”102

To their east, the Kazakh faced another rising empire, the Oirat. In 1643, Oirat armies under Erdeni Baatur Khung-Taiji, the father of Galdan Khan, led the first major Oirat expedition into Semirechie, defeating Kazakh armies under Khan Jahangir (d. 1652). In 1681, under Galdan Khan, the Oirat renewed their attacks on the Kazakh Great Horde, and over the next four years they seized much of the southern Kazakh steppes. This gave the Oirat temporary control not only of the eastern branch of the Silk Roads, but also over parts of the new, northern branches from Bukhara to Siberia.103

The defeat of Galdan in 1696 temporarily eased Oirat pressure, and the Kazakh hordes united once more under Sultan Tawke (r. 1680–1715). In Kazakh tradition, Sultan Tawke is regarded as the creator of the most important Kazakh code of laws, the “Zhety Zhargy” or “Seven Laws.” This was probably drawn up in the last third of the seventeenth century, during the Oirat wars.104 But in 1723, after the revival of Oirat power, Sultan Tawke's successor, Pulat Khan (1718–1730), suffered a massive defeat near Talas at the hands of Galdan's successor, Tsewang Rabtan (1697–1727). The Oirat sacked several Syr Darya cities including Turkestan and Tashkent. These defeats are known in Kazakh histories as “the great calamity.” Retreating Kazakh armies and their herds inflicted great damage on major Central Asian cities, including Samarkand and Khiva.

The Oirat threat drove Kazakh leaders to formally seek Russian protection for the first time, an event that marks a fundamental shift in power relations in the Kazakh steppes. Khan Abulkhair of the Lesser Horde (r. 1718–1748) accepted Russian overlordship in 1731, realizing that his 400,000 followers could no longer maintain secure migration routes without Russian goodwill. In 1726, he asked permission to enter Russian territory. In 1730, Empress Anna Ioannovna granted his request for Russian citizenship, on terms similar to those granted earlier to the Bashkir and Kalmyk. Many of Abulkhair's nobles opposed these negotiations, fearing that they not only dishonored the Kazakh, but also weakened them commercially and militarily. Russia now required the Kazakh to protect and guide Russian caravans, and accept Russian instructions about their migration routes.

Russian negotiations with Kazakh leaders proved extremely important and we have detailed notes on them from Mohammed Tevkelev, a Russian translator and diplomat, and a Muslim Tatar. It was during these negotiations that the idea first surfaced of building a fort at the Or river (later Orenburg/Orsk) where Kazakhs could trade with Russian merchants. In 1733, Tevkelev prepared a formal memorandum recommending the building of a fort at Orenburg, under the pretense that it had been requested by the Kazakh. These ideas would shape Russian policy in the region for many decades.105 In 1732 and 1740, the khans of the Middle Horde made similar agreements on behalf of their 500,000 odd followers, though, like all Kazakh khans, they lacked the authority to enforce such agreements on their followers.106

It would take almost a century before the Russian Empire could claim secure control of the Kazakh steppes. But these early concessions undermined the already limited power of Kazakh khans. By the middle of the eighteenth century, no Kazakh groups could flourish without Russian support and goodwill.

TRANSOXIANA

After the end of the Shibanid dynasty in 1598, Transoxiana was divided between regional dynasties based in Bukhara, Khiva, and eventually Kokand. These dynasties would dominate the region for over two centuries. The khanates (or emirates, as many rulers were not Chinggisids) should not be thought of as territorial states. Each dynastic system teetered perpetually on the brink of fragmentation, in a world of constantly shifting alliances in which many regional leaders claimed Chinggisid heritage. Like earlier polities in Transoxiana, the three major dynasties ruled city-based mobilizational systems, and had to continuously negotiate for influence over outlying towns and cities and regional steppe armies. As a result, the borders of the new khanates were neither clear nor stable, and their power waxed and waned, depending on the skills of particular rulers, and changes in the productivity of agriculture and the profitability of international commerce.

In Bukhara, Jani Muhammad, a Chinggisid and the son of a refugee from the Russian conquest of Astrakahan, seized power in 1599. The Janids or Ashtarkhanids would rule Bukhara until the mid-eighteenth century. The first powerful Ashtarkhanid khan, Imam-Kuli (1611–1641), drove the Kazakh out of Tashkent in 1613, undertook repairs to Bukhara's irrigation systems, and maintained stability during a long reign. But he made little effort to enforce his authority over regional Uzbek chiefs. He was aware of the rising power of Muscovy, and made efforts to contact Moscow, even promising to release Slavic slaves. The first mission, sent in 1613 during the Time of Troubles, was stopped before it got to Moscow. A second mission, dispatched in 1619, prompted a return mission from Moscow, led by Ivan Kokhlov. Unfortunately, Kokhlov's reports on Transoxiana were so hostile that they discouraged Muscovy from sending of further missions.107

Imam-Kuli eventually went blind, abdicated in favor of his younger brother, and set off on a pilgrimage to Mecca. That journey took him through Persia, where a still-surviving portrait of him was painted.108 Later, Bukhara's irrigation systems fell into disrepair, which may help explain the appearance of economic decline suggested by debasement of the coinage.109 In the early eighteenth century Bukharan power fragmented, leaving a network of city-states that owed merely nominal obedience to Bukhara.110 After 1709, Bukhara lost control of the Ferghana valley, which eventually became the independent khanate of Kokand.

In 1740, the Persian leader Nadir Shah (r. 1736–1747) launched a series of devastating invasions of Transoxiana, which mark a turning point in Central Asian history.111 From this point on, non-Chinggisid rulers would become increasingly important. Symbolically, at least, these changes mark the end of the Chinggisid dynastic era in Central Asia. The last Chinggisid khan of Bukhara was murdered in 1747.

Bukhara itself became increasingly conservative and theocratic in its attitudes and methods of rule:

the city and khanate crystallized into an almost classical pattern of a Muslim polity of its time, cherishing and even enhancing traditional values while ignoring or rejecting the vertiginous changes initiated by the Europeans but now reaching other parts of the world. Most khans, especially the virtuous Abdalaziz (ruled 1645–81), were devout Muslims who favored the religious establishment and adorned Bukhara with still more mosques and madrasas.112

The arts and theology thrived while political power decayed. Though Bukhara flourished as a center of crafts, political fragmentation reduced regional trade, as regional chiefs levied local tolls. By the middle of the eighteenth century, Khan Abulfayz controlled little beyond his royal palace. Nevertheless, Bukhara remained an important center of international trade. A late eighteenth-century observer noted that “there is always a multitude of people from Persia, India, China, Kokand, Khujand, Tashkent and Khiva, as well as Russian Tatars, Georgians and various nomadic peoples,” and it was even possible to find European clocks and Frankish brocades.113

Further north, Khorezm had long threatened to break from Bukhara's control. In 1619, Khan Arab Muhammad I (r. 1603–1623) established a new Shibanid dynasty of Khorezmian rulers, the Yadigard, with its capital at Khiva. The Yadigard dynasty would survive until the early eighteenth century. Turbulence in the steppes and in the Syr Darya cities controlled by the Kazakh reduced the flows of commercial wealth that had traditionally sustained the wealth and power of Khorezm. But Khiva remained active in the slave trade. Though its ruling elites were mainly Uzbek, the khanate's population of about 700,000 people included a huge, and mainly Iranian, slave population.114 Slaves were used partly to maintain Khiva's extensive system of irrigation canals, which covered hundreds of kilometers, allowed the production of wheat, fruit, and cotton, and probably supported two thirds of the khanate's population.115

Khiva was the most ecologically and politically compact of the Central Asian khanates. But it faced constant pressure from Turkmen nomads on its borders, who often enjoyed the support of Sufi holy men.116 Rulers negotiated military coalitions with Turkmen tribes, but this was never easy because the Turkmen, unlike most Inner Eurasian pastoralist groups, had extremely egalitarian tribal structures. Blood-money payments, for example, were the same for all Turkmen, unlike other steppe regions, in which they varied according to the status of those involved. Political egalitarianism explains why the Turkmen rarely had strong leaders except in times of war, when they would elect wartime leaders or serdars, who were sometimes known as “khans.”117

Abulghazi Bahadur Khan (r. 1643–1663), the son of the founder of the Yadigard dynasty, was an able soldier as well as a historian. Like Babur, he wrote in Turkic, a reflection of the fact that the population of Khiva, unlike that of Bukhara, was mostly Turkic speaking. Also like Babur, he had traveled widely in his youth, in Transoxiana, Persia, and even to the Kalmyk lands.118 The last effective Yadigard khan was Shir Ghazi (1715–1728), who successfully defeated a Russian military expedition of 300 men, sent by Peter the Great in 1717–1718, and led by Bekovich Cherkasskii. That expedition reflected Peter's over-ambitious dreams of building a trading empire from Russia through Central Asia to India.119