[10]

1850–1914: THE HEARTLAND: CONTINUED EXPANSION AND THE SHOCK OF INDUSTRIALIZATION

A NEW ENERGY REGIME: THE FOSSIL FUELS REVOLUTION

In the nineteenth century, the old rules of mobilization were transformed by the energy bonanza of fossil fuels. Like a gold strike, fossil fuels created entirely new forms of wealth and power, made millionaires and paupers, and generated a feverish global rush for energy, resources, and new technologies. These changes would affect the Inner Eurasian heartland first, because that was the region of Inner Eurasia most sensitive to global competition. But over the next century, the fossil fuels revolution and its associated technologies would transform the whole world, including all of Inner Eurasia.

Since the beginnings of agriculture, some 10,000 years ago, most human societies had been powered by what E. A. Wrigley called the “organic energy regime.” They mobilized energy from recent photosynthesis: from human and animal labor (fed and fueled by the annual harvest), from wood, and in smaller amounts from wind and water power. Ultimately, this energy came from sunlight, captured by plants through photosynthesis, and diverted and mobilized for human use by agriculturalists. Eat wheat, and you are ingesting sunlight trapped within the last 12 months. Burn wood and you are releasing sunlight trapped during the lifetime of a tree. As the classical economists, such as Smith and Ricardo, understood, this meant that the energy flows mobilized by humans were limited by the annual harvest from fields and woodlands, in other words, by the area of land under crops and trees. Eventually, they argued, even the most efficient economies would hit an energy wall. Resource flows would slow, productivity would fall, businesses would fail, wages would crash, and societies would face the sort of demographic and resource crisis that all other organisms face when they have filled their ecological niche. This would be the end of growth.

In a country fully peopled – wrote Adam Smith – in proportion to either what its territory could maintain or its stock employ, the competition for employment would necessarily be so great as to reduce the wages of labour to what was barely sufficient to keep up the number of labourers, and, the country already being fully peopled, the number could never be augmented.1

In the late eighteenth century, signs were multiplying that growth was indeed slowing in the world's most advanced economies, such as the Netherlands. By Adam Smith's time, as A. W. Crosby puts it, “Humanity had hit a ceiling in its utilization of sun energy.”2

But growth did not end, because humans learnt how to tap into larger, and much more ancient supplies of photosynthetic energy, stored in fossil fuels. The breakthrough came in the eighteenth century, with technologies that made it possible to exploit the huge stores of fossilized photosynthetic energy buried and concentrated over several hundred million years in coal, oil, and natural gas. Many societies had burnt fossil fuels for heat. The revolutionary trick was to generate mechanical energy from them at reasonable prices. The first efficient coal-fired steam engines led human societies into an entirely new energy regime. Overnight, machines powered by fossil fuels gave access to a virtual labor force many times larger than that provided by humans and animals. Cheap energy, in its turn, stimulated the burst of innovations that would transform societies throughout the world in the nineteenth century.

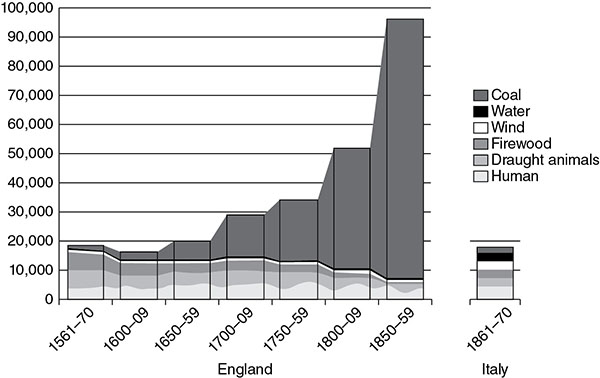

The crucial technical breakthrough came in England, a once remote island off the north-west of the Eurasian landmass, with ambitious governments, a dynamic economy, trade links that spanned the globe, an increasing fascination with science and engineering, and large amounts of accessible coal. Here, from the sixteenth century, coal was beginning to replace wood as a primary source of heat in manufacturing and households. Its use encouraged investment in better ways of mining, moving, and using coal. It encouraged canal building and the introduction of the first, crude, steam engines to drain coal mines. In the late eighteenth century, these same pressures yielded the James Watt steam engine, the first machine that could turn the heat from fossil fuels into mechanical energy, cheaply and efficiently. By 1850 England had successfully transcended the energy limits of the agrarian era. The amount of energy mobilized by each person in England and Wales had increased by almost five times, from the Neolithic maximum of about 20,000 Megajoules per person to almost 100,000 Megajoules (Figure 10.1). In effect, each person had acquired four new energy slaves. In 1776, James Watt's backer, Matthew Boulton, told Dr. Johnson's biographer, Boswell: “I sell here, sire, what all the world desires to have – POWER.”3

Figure 10.1 Increasing energy consumption in early modern England and Wales. Wrigley, Energy and the English Industrial Revolution. Reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Once the technologies had been developed to extract cheap mechanical energy from fossil fuels, they multiplied the power and divided the cost of production and transportation. Wrigley gives a striking illustration of how fossil fuels could magnify the productivity of human labor.4 A coal miner using about one horsepower/hour of his own energy could produce enough coal to generate 27 times that much energy if it was burnt in a steam engine operating at 1 percent efficiency. Even on these conservative estimates, it was as if each miner had been joined by 26 virtual labor slaves.5 Or we can think of the energy from fossil fuels in terms of woodland equivalents. In 1750, the amount of energy supplied in England and Wales by coal would have required about 4.3 million acres of woodlands; by 1800 it would have required c.11.2 million acres; and by 1850 about 48.1 million acres. These areas are the equivalents, respectively, of 13 percent, 25 percent, and 150 percent of the total area of England and Wales.6

Steam engines stimulated economic and technological change in many ways. They gave access to more cheap coal, as most of the world's coal fields lie so deep that they required steam engines to drain them. Fossil fuels stimulated innovation by posing new technological and commercial challenges, such as how to transport coal cheaply, or how to use steam engines to manufacture textiles. Increasing supplies of cheap energy drove other resource booms by lowering the costs of producing, transporting, and manufacturing metals, timber, cotton, and many other raw materials. Cheap energy also stimulated the search for new industries, such as the chemicals industry, many of whose early products were based on by-products of coal use. In 1970 almost 200 different chemical products were based on coal.7 By the twentieth century, fossil fuels were being used to produce fertilizers that made it possible to feed a world of several billion people. Humans had learnt, in effect, how to eat oil.

The sharp upturns at the end of each section of Figure 10.2illustrate the scale of the demographic, economic, and climatic changes that have transformed the world since the beginning of the fossil fuels revolution.8 But the graph also illustrates the costs of the fossil fuels revolution, which pumped back into the atmosphere and oceans vast stores of carbon dioxide that had been buried in fossil fuels over 300 million years. Today, increasing levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide and other “greenhouse” gases are beginning to transform global climates and acidify the world's oceans.

Figure 10.2 Hockey sticks: accelerating growth rates for population, life expectancy, GDP, and impacts on the climate system and biosphere. Brooke, Climate Change, Figure IV.3. Reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Since at least the nineteenth century, historians have debated the causes of these momentous changes that have created today's world. This is not the place to review those debates in detail, but in a history of Inner Eurasia, it is helpful to distinguish between two broad types of explanation for modern forms of growth, between two possible drivers of growth.

Most historians have explained the Industrial Revolution as a product of increased efficiency and innovation, driven by entrepreneurial competition and expanding markets. This is the “market driver of growth,” and it is driven primarily by the commercial strategies of mobilization that Marx called “capitalism.” Unlike traditional strategies of direct mobilization, which focused on the mobilization of resources rather than their efficient use, commercial mobilization drove growth by generating managerial and technological innovations that encouraged more efficient use of what was mobilized. Perhaps, as Marx argued, modernity is a product of the rapid spread of commercial methods since the sixteenth century. In the work of sociologists, the market driver of growth has often been linked to institutional “modernization,” to changes that created the preconditions for more efficient markets: clearer and more predictable legal structures and more rational and efficient forms of administration.

There can be no doubt that modern forms of capitalism stimulated innovation on scales never seen before in human history, and that helps explain the entrepreneurial and scientific creativity that generated the crucial technological breakthroughs. However, as E. A. Wrigley has argued in numerous publications, without new sources of energy, even the most innovative societies faced limits to growth. So, to explain the vast changes that have created today's world, we need to focus on the breakthrough innovations that released new flows of energy that allowed modern societies to escape the constraints of the organic economy.9 Here is our second, and perhaps most crucial, driver of modern growth: the vast new flows of energy unleashed by the fossil fuels revolution.

We can call this driver of growth the “fossil fuels driver.” It was very specific in its operation, and it was completely unexpected.

The Industrial Revolution – writes Wrigley – was unexpected by contemporaries. … Like Pandora and her husband when [Pandora's box] was opened, nothing in their past experience had prepared people at the time for what was to follow. The possibility of a transformation which would radically enhance the productive powers of society was at the time generally dismissed as idle optimism.10

Only in the mid-nineteenth century did economists of the generation of Arnold Toynbee, W. S. Jevons, and Karl Marx begin to understand that coal might generate growth on a scale that market forces alone could not explain. Without fossil fuels, modern societies are unthinkable. As Wrigley puts it, “An industrial revolution is physically impossible without access to energy on a scale which does not exist and cannot be secured in organic economies.”11 Figure 10.3gives some sense of the contribution of fossil fuel energy to today's world. To appreciate the importance of fossil fuels, it is enough to imagine what would happen if electricity generation ceased, gas supplies were cut, water pumps shut down, and supplies of oil and gasoline dried up overnight, forcing the global economy to depend on flows of energy no larger than those of 1850. After an initial period of chaotic and violent adaptation, the entire world would be driven back to the pre-industrial era of organic energy.

Figure 10.3 Increasing global energy supplies, 1850–2000, adapted from Crosby, Children of the Sun, 162.

These crude distinctions between different drivers of mobilization and growth can help illuminate many aspects of Inner Eurasia's history in the era of fossil fuels because they raise a fundamental question: What is the most effective way of mobilizing the energy bonanza of the fossil fuels revolution? How could traditional mobilizational systems best tame and harness the staggering energies of the fossil fuels driver?

Once fossil fuels technologies existed, it was clear that the power and wealth of entire mobilizational systems would depend on exploiting those technologies as effectively as possible. In Russia, those possibilities had been glimpsed even in the eighteenth century; in 1771, the Russian government offered James Watt a salary of £1,000 just on the rumor that he was building an improved steam engine.12 By the mid-nineteenth century, the importance of fossil fuels was increasingly apparent because the first countries to mobilize fossil fuel energy on a large scale generated astonishing economic, political, and military power within just a few generations. By the late nineteenth century they were global superpowers and ruled global empires. Powered by the ability to mobilize the energy of fossil fuels, industrialization had generated revolutionary new forms of transportation, including steamships and railways, which slashed the costs of moving people, goods, and armies across continents and oceans. Industrialization had also transformed military technology. “In terms of effective firepower the disparity between the rifle of World War One and the Napoleonic musket was greater than between the musket and the bow and arrow.”13 Finally, industrialization drove technological and scientific creativity, as investors, entrepreneurs, and governments sought new ways to profit directly or indirectly from the bonanza of cheap energy.

THE FOSSIL FUELS REVOLUTION IN INNER EURASIA: NEW CHALLENGES AND POSSIBILITIES

How should Inner Eurasian governments react to these revolutionary changes? Did their traditional mobilizational strategies prepare them to exploit the fossil fuels bonanza effectively?

The mobilizational machine built up in Muscovy and Russia over several centuries, like that of most traditional empires, was dominated by “direct mobilization.” Market forces, or “commercial mobilization,” played a subordinate role. In the past, direct mobilization had proved very effective even at innovating, because you could buy and deploy new technologies developed elsewhere. This is what Muscovite governments had done in the seventeenth century when faced with the challenge of gunpowder warfare. It was what the Mongol Empire had done when it hired Chinese siege equipment and military engineers, or scribes and financial managers.

But fossil fuels technologies were more complex than the gunpowder technologies of the seventeenth century. Would they work without the constant flow of large and small innovations and the careful managerial techniques generated within market economies? Would not excessive government control stifle innovation and investment? And could Russian governments learn to protect the fundamental institutions of property, banking, and law that were necessary for an effective and innovative market economy? If the market driver was in fact an essential ingredient of the fossil fuels revolution, Russia's traditional mobilizational methods would need a fundamental renovation.

These distinctions between different drivers of growth may help explain what might otherwise seem an anomalous feature of Inner Eurasia's modern history, and that of neighboring China. In the twentieth century, modern states in Russia and China achieved spectacular rates of industrialization after abolishing the market driver. To many, that was proof that capitalism and markets were not essential for the building of modern societies. For a time, the mobilizational strategies of the agrarian smychka seemed to work surprisingly well, even in the era of fossil fuels. However, in the late twentieth century it became clear that strategies of direct mobilization were less effective at managing mature fossil fuels economies, in all of which the market driver has played a significant role.

These distinctions between different drivers of growth are much easier to see in retrospect than they were at the time. And governments had to make difficult decisions. As they faced the complex challenge of keeping up with a rapidly industrializing West, we see governments in Russia, as in many other late-industrializing countries, twisting and turning in a pragmatic search for a workable middle ground that would allow modern forms of growth while preserving as much as possible of the traditional mobilizational structures on which their power was based. Debates over these complex challenges would drive fundamental policy decisions in Russia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and again in the early decades of the Soviet era.

What was obvious to Chinese and Russian leaders after the Opium Wars and the Crimean War was the terrifying increase in the military and economic power of Europe. Tonio Andrade has argued that Chinese gunpowder technology did not lag significantly behind that of the West even in the eighteenth century. But by the mid-nineteenth century, “the Chinese and British were in two different historical eras.” The Chinese were still in an era of cold weapons; the British had entered an era of “hot weapons,” manufactured and used with entirely new levels of scientific skill and precision.14 In the mid-nineteenth century, the challenge was particularly urgent for China, whose military technologies had stagnated during almost a century of relative peace after the defeat of the Zunghar Empire. Suddenly, it found itself threatened by highly industrialized European rivals who arrived by sea. China had rarely faced the danger of sea-borne invasion, and never faced iron-clad gunships with cannon, so it was completely unprepared, and its leaders had little time to consider how best to react. The Russian Empire, however, was protected by its location within Inner Eurasia. That gave Russian governments more time to consider their options.

This chapter will describe how the Russian heartlands were affected by the global changes of the late nineteenth century. The next chapter will focus on the rest of Inner Eurasia, which was, as yet, largely unaffected by the fossil fuels revolution. It will trace the continuing momentum of Russian expansion in a rapidly industrializing world, and the slow withdrawal of a declining China from its Inner Eurasian Empire.

THE IMPERIAL HEARTLAND: 1850–1900

Defeat in the Crimea forced Russia's rulers to take industrialization seriously. Before that war, the Russian Empire still looked like a global superpower. It was the largest contiguous empire in the world; it had the largest army in Europe; and it overshadowed Inner Eurasia and eastern Europe. It had even taken small steps towards industrialization. In the 1840s, industrial production grew rapidly from a small base, as the number of factories and mills rose from c.5,500 in 1833 to 9,848 in 1850, many of them using steam engines. Growth was particularly rapid in cotton production, and the first railways linked St. Petersburg to the royal palace of Tsarskoe Tselo and to Moscow.15 Russia's many military and diplomatic successes in the early nineteenth century explain why defeat in the Crimean War (1853–1856) came as such a shock. Like the Time of Troubles in the early seventeenth century, the Crimean War exposed dangerous weaknesses in Russia's mobilizational system.

THE DILEMMAS OF REFORM

Problems began with the army. Russia's army was expensive because it was huge, and permanently under arms. The costs of the Crimean War brought the government close to bankruptcy. Lifelong (or virtually lifelong) military service made it difficult to expand the size of the army in wartime because there were few trained reserves. Moving the army rapidly from front to front was difficult because of Russia's size and its pre-industrial, horse- and oxen-powered transportation networks. In 1860, Russia had only 1,600 kilometers of rail and even in 1870 it had only 8,000 kilometers of paved military roads.16 Poor transportation made it difficult to supply soldiers even with basic necessities such as clean drinking water, which helps explain the poor health of Russian troops. These weaknesses were compounded by rigidity in the methods used to recruit, train, and support an army based on the archaic institution of serfdom.

In 1853, the government responded to invasion as it had in 1812. It launched a massive recruitment drive that added a million new troops to a standing army of 980,000 men. However, resistance to recruitment and unrest in the borderlands meant that most troops were deployed not in Crimea but in Poland, the Caucasus, or in regional garrisons. In any case, there were no railway lines to Crimea. So, for much of the war, Russia's enemies, who had brought their armies and supplies by sea, outnumbered the Russians.

The war exposed the limitations of Russian weaponry. Most Russian soldiers still used smoothbore muskets that had changed little since the time of Peter the Great.17 They had a range of about 60 paces, while the Minié rifles of their opponents had a range of 200 paces. Allied artillery proved its superiority during the siege of Sevastopol, inflicting huge casualties. Russia's cannon were smoothbore weapons, with less accuracy and a shorter range; and their opponents had much more ammunition.18 Finally, it became clear that a modern army required better educated and motivated troops. While the Russian mobilizational system produced large numbers of tough, courageous, and often ingenious soldiers, most were also illiterate and poorly trained. This was hardly surprising as both serfowners and village communes had an interest in sending to the army their least healthy, least able, and least cooperative members.

These problems went to the heart of the Russian system, because the army was so deeply embedded in Russian society. Reforming the army would mean transforming Russian society as a whole, just as the building of Muscovy's cavalry armies had transformed the lives of Muscovite nobles and peasants.

Nicholas I died in 1855. A year later, his son Alexander II (r. 1855–1881) agreed to peace terms at a conference in Paris. Not since Narva in 1700 had the Russian Empire suffered such humiliation, and many in government circles began to think that major reforms were overdue. P. A. Valuev, a future Minister of Internal Affairs, wrote in 1855:

in waging war with half of Europe it was impossible any longer to hide behind the curtain of official self-congratulations to what degree and precisely in what areas of state power we lagged behind our enemies. It turned out that our fleet lacked exactly those ships and our army exactly those weapons needed to equalize the combat.19

But what needed to be reformed? What should be preserved? And how should the government tackle the delicate task of renovating its mobilizational machinery to deploy modern technologies, while keeping the machine working at almost full power?

THE “GREAT REFORMS”

In the decade after the Crimean War, the government of Alexander II launched a series of fundamental reforms known as the “Great Reforms.” These reflected a widespread conviction in government circles that reform required more than the introduction of new technologies. It also required a more fundamental social, economic, and legal renovation to incorporate some of the advantages of the market driver and, perhaps, even some degree of political freedom.

Within the circle of advisers around the new monarch, many believed it was necessary to abolish serfdom itself, the foundation of Russia's mobilizational system since the seventeenth century. Dmitrii Miliutin, who would preside over a massive reform of the army in the 1870s, argued that serfdom blocked military reform by preventing the introduction of shorter terms of service to build a trained reserve. This was because those demobilized from the army were automatically freed from serfdom, so that short terms of service would in practice mean a slow, de facto abolition of serfdom. Much better, he argued, to cut the knot of serfdom and recruit soldiers from the whole population, but for shorter terms. Others within the nobility and the upper bureaucracy were persuaded by the argument of economic liberals: that there was a link between freedom and economic growth. Growth, they argued, would be stifled as long as landlords relied on their monopolistic rights to serf labor, rather than having to pay wages. And peasants would continue to work inefficiently as long as they were not paid. It was vital, they argued, to encourage market forces that could encourage innovation and raise productivity in the country's most important sector, agriculture. Perhaps, at last, Russia had to turn from extensive to more intensive, market-driven strategies of growth. As early as 1841, a landowner told a government official:

A free man knows that if he does not work he is not going to be fed for nothing, and as a result he works hard. Here is my own experience: twenty versts from my estate of Zemenki, I have some unsettled land which I have worked using my own peasants, not under barshchina [labor dues or corvée], but by hiring them under a free contract. The same peasants who idle about on barshchina work extremely hard there and are even willing to work on holidays, as long as no one stops them. And they so value this work that they are reluctant even to annoy the overseer.20

Some nobles and officials argued that serfdom, like slavery, was simply wrong. Others argued that serfdom would provoke increasingly dangerous peasant revolts like the terrifying Pugachev uprising in the late eighteenth century.

Yet most nobles and officials still found it hard to imagine Russian society without the coercive ties of serfdom. As one official recalled:

[Noble] protests [against reform] expressed in vigorous terms more or less the same idea – that the emancipation of the serfs was premature; the result of the change, … would be that the estate owners would remain without working hands, the peasants because of their natural indolence would not work even for themselves, the productivity of the state would decrease, causing general inflation, famine, disease, and nationwide misery. At the same time would come insubordination on the part of the peasants, local disorders followed by widespread rioting – in a word, they predicted another Pugachev rebellion with all its horrors and with the addition of a “deeply plotted” democratic revolution.21

As one noble put it, “Why change that political system that made [Russia] a first-class power in the world? To undermine its foundations, everything that constitutes its strength and essence, is ill-advised and dangerous.”22

Paradoxically, Russia's long-established traditions of elite discipline allowed the government to introduce major reforms against the resistance of most nobles. In 1856, Alexander II invited the nobility to discuss how to reform the system:

the existing system of serf-owning cannot remain unchanged. It is better to begin abolishing serfdom from above than to wait for it to begin to abolish itself from below. I ask you, gentlemen, to think of ways of doing this. Pass on my words to the nobles for consideration.23

As Alexander should have expected, Russia's traditional political culture discouraged political initiatives, and nobles met his invitation with silence. When the government did get a more positive response, it was too radical. Nobles in Tver’ province interpreted Alexander's invitation as a step towards a consultative political system that might compensate nobles politically for the loss of authority over their serfs. In 1862, the Tver’ nobility went even further, calling for an elected assembly representing the people as a whole. The government rejected the idea outright.

In 1861, the government abolished serfdom unilaterally. One of its primary goals was to avoid the twin dangers of revolt from below or a coup from above by balancing the gains and losses of nobles and peasants. The Emancipation Statute abolished serfdom in law, and deprived landlords of most police powers over their peasants. It granted ex-serfs full possession of their households, and temporary access to the household allotments (usad'by) they had farmed for their own use. It also introduced a complex mechanism by which peasants could collectively buy the land they farmed from their landlords, using long-term government loans. Under this mechanism, which eventually became compulsory for both nobles and former serfs, peasant communes were obliged to pay off government mortgages in the form of “redemption payments” over 49 years. But the communes would continue to own the land collectively and redistribute it periodically to individual households, preserving the ancient tradition of “collective responsibility” for the redemption payments. By limiting the amount and inflating the price of the land that peasant communes could purchase, the government ensured that few peasants would be self-sufficient. This displeased the peasants, but guaranteed landlords a supply of cheap wage labor to replace free serf labor.

These arrangements tied peasants to their allotments and to their communes for many decades, slowing permanent migration to the towns, even as rapid population growth reduced the average size of allotments. Nevertheless, the severing of ties with their landlords forced peasants to engage more with market forces. As the English observer, Mackenzie Wallace, noted, as long as they were the property of their masters, most peasants had lived in a patriarchal world that shielded them from the market:

If the serfs had a great many ill-defined obligations to fulfill [under serfdom] – such as the carting of the master's grain to market … they had, on the other hand, a good many ill-defined privileges. They grazed their cattle during a part of the year on the manor land; they received firewood and occasionally logs for repairing their huts; sometimes the proprietor lent them or gave them a cow or a horse when they had been visited by the cattle plague or the horse stealer; and in times of famine they could look to their master for support. All this has now come to an end. Their burdens and their privileges have been swept away together, and been replaced by clearly defined, unbending, unelastic legal relations. They now have to pay the market price for every stick of firewood which they burn, for every log which they require for repairing their houses, and for every rood of land on which to graze their cattle. Nothing is now to be had gratis. … If a cow dies or a horse is stolen, the owner can no longer go to the proprietor with the hope of receiving a present, or at least a loan without interest, but must, if he has no ready money, apply to the village usurer, who probably considers 20 or 30 per cent as a by no means exorbitant rate of interest.24

Neither peasants nor landlords were happy with the reform, and there were protests from above and below. However, the reformers balanced the gains and losses with considerable skill, so that landlords and peasants soon came to grudging terms with the reforms. Peasant disturbances faded away within two years, and upper-class resentment dissipated in the gentry grumbling that Tolstoy described in Anna Karenina.

The abolition of serfdom cleared the way for other reforms. In 1874, Dmitrii Miliutin, the Minister of War, carried through the most fundamental military reform since Peter the Great. From henceforth, the army would recruit from all classes, and recruits would be released into the trained reserve after terms of service that were reduced from 7 years to 18 months for all with secondary education and to just 6 months for those with university education.25 Officer training was improved, and recruits were taught reading and writing. This change would help raise literacy in society as a whole. In the late eighteenth century, only 6 percent of Russia's population was literate. By 1850 the proportion had risen to 19 percent, and by 1913 to 54 percent, as a result of both education within the army and the spread of primary education.26 The military reforms made a difference that was apparent in Russia's next major war, against Turkey, in 1877. But the limits of Russian power became apparent once again at the 1878 Conference of Berlin, when the major European powers imposed a treaty denying Russia many of the fruits of victory, including the creation of a powerful Bulgarian state that would have enhanced Russian influence in the Balkans.

In 1864, the government established elected local government assemblies, or zemstva, and reformed the judicial system. These were significant gestures towards democratization, but their real impact was limited. Though separated from the bureaucracy and elected by all classes, the zemstva had limited administrative and fiscal powers and could be overruled by local governors. In practice, they were dominated by the nobility. The judicial reform introduced open courts, trial by jury, and some degree of judicial independence, but much of the population remained beyond their jurisdiction, and in the 1870s, as it faced the beginnings of a revolutionary movement, the government bypassed the new courts by introducing martial law in many provinces. These and other reforms, including a relaxation of the censorship and of government control over the universities, showed some willingness to relax the central government's grip on society as a whole. But in practice, like the local government reforms of Ivan IV (which also introduced elections), their real effect may have been to enhance the government's power by reducing the authority of the landowning class and increasing that of government officials.

Nearly bankrupt at the end of the Crimean War, the government also reformed its finances by shifting the burden of taxation towards indirect taxes and commercial activity. The poll tax, established by Peter the Great, was abolished in 1885; in practice it was replaced by the redemption dues that peasants now paid for their land. The shift away from direct taxes showed the increasing importance of market forces. Greater shares of government revenue now came from indirect taxes such as the excise on vodka sales (which accounted for up to 20–35 percent of revenue for most of the nineteenth century), from protective tariffs on imported goods (whose contribution rose from 12 percent in 1877 to 33 percent in the 1890s), and from the state-managed railways.

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CHANGE

Though powerful, the government was not the only shaper of economic and social change. Many other forces were in play, and in the late nineteenth century the market driver played an increasing role as Russia began to industrialize. But the exact nature and speed of Russia's evolution towards capitalism has been the subject of long and complex debates that began in the late nineteenth century. It may be helpful to distinguish between three main interpretations.

First, given the power and reach of the Russian autocracy, many historians have focused on the government's leading role in economic and industrial change. Alexander Gerschenkron argued that industrialization really began only in the 1890s, when Sergei Witte, the Finance Minister of Tsar Alexander III (r. 1881–1894), introduced a strategy of government-led industrialization. His approach was modeled on the protectionist strategies used by the USA in the early nineteenth century and theorized by the German economist Friedrich List.27 The government introduced high tariffs both to raise revenue and to protect its infant industries; it maintained pressure on the peasantry to pay redemption dues; and it placed the ruble on the gold standard in order to raise foreign loans for industrial development. With the money raised from taxation, tariffs, and loans, the government funded a massive program of railway building, with the Trans-Siberian railway as its centerpiece, and offered subsidies for the mining and metallurgical industries that would supply the energy and metals needed for the railways.

A second interpretation stresses the failure of economic and political modernization in late Tsarist Russia, and the preservation of traditional mobilizational structures. It argues that Tsarist attempts at modernization failed to generate rapid industrialization, but did create many of the tensions that would lead to revolution. Robert Allen, for example, argues that “The tsars did not lay the groundwork for rapid, capitalist development. In the absence of the communist revolution and the Five-Year Plans, Russia would have remained as backward as much of Latin America or, indeed, South Asia.”28 Traditional legal, social, and political structures and limited or uncertain property rights stifled entrepreneurial activity, discouraged foreign investment, and stunted growth in the largest sector of all, agriculture, creating a small but discontented industrial working class and massive rural unrest.

A third interpretation sees the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a period of vibrant economic growth and rapid industrialization. Independently of the government's plans, powerful commercial forces were at work, laying the foundations for a vigorous market economy. In this view, an eventual breakdown was far from inevitable. The system collapsed mainly because of a failure to manage the tensions caused by rapid growth. This position has been defended vigorously by Paul Gregory.29 The argument that follows borrows much from Gregory's research and from his interpretation of the economic and social history of Russia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But it emphasizes in particular the role of fossil fuels and the technologies needed to exploit them.

Gregory argues that there was significant economic growth even before the 1890s. Population growth was an important driver of economic growth, as the empire's population grew from 74 million in 1858 to 128 million in 1897, and 178 million in 1914. Its human resources had more than doubled in 50 years. The peasant population alone grew from 32 million in 1857 to more than 90 million by 1914 as a result of natural increase.30 Population growth was driven partly by improved medical knowledge and services. Boris Mironov has tracked changing demographic patterns in some detail, showing that, as mortality rates fell faster than fertility rates, populations increased particularly fast from the mid-nineteenth century.31 In the same period, Russia's national income rose by almost four times, even more rapidly than its population, which means there was also a significant, if modest, increase in per capita output (c.85 percent). Between 1861 and 1913 the average rate of growth of total output was similar to that of other major industrialized countries. It was surpassed only by the USA, Canada, Australia, and Sweden.32

As Gerschenkron argued, the building of a national railway network was another powerful driver of growth, as it was in all countries with large land areas, because it slashed transportation costs by land and cheapened the movement of labor and of export goods, particularly grain, cotton, and textiles. Indeed, the geographer Halford Mackinder, writing in 1904, argued that railways were revolutionizing geopolitics by allowing such rapid movement of troops and supplies over land, that for the first time in history, large land empires could emerge as global superpowers.

A generation ago steam and the Suez canal appeared to have increased the mobility of sea-power relatively to land-power. Railways acted chiefly as feeders to ocean-going commerce. But trans-continental railways are now transmuting the conditions of land-power, and nowhere can they have such effect as in the closed heartlands of Euro-Asia, in vast areas of which neither timber nor accessible stone was available for road-making. Railways work the greater wonders in the steppe, because they directly replace horse and camel mobility, the road stage of development here having been omitted.33

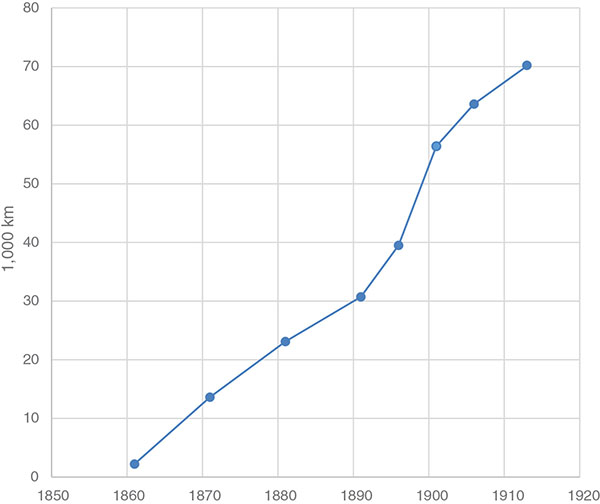

As early as the 1860s, the government started offering generous incentives to entrepreneurs willing to build railways or the metallurgical factories needed to manufacture track and rolling stock. The empire's railway network grew from 2,000 kilometers in 1861 to over 30,000 kilometers in 1891 (Figure 10.4). By the 1890s, the spectacular imperial successes of the other Great Powers and the equally spectacular decline of traditional powers such as the Ottoman and Qing empires had persuaded the Russian government that it had to support economic growth more aggressively. Under Sergei Witte, an entrepreneurial Minister of Finance of non-noble birth who had risen through the railway administration, the government began a massive program of railway building. Its centerpiece was the Trans-Siberian railway, 8,000 kilometers long, with hundreds of bridges, cuttings, and tunnels. It reached from Moscow to Manchuria and Vladivostok.

Figure 10.4 The Russian railway network, 1861–1913. Adapted from Christian, Imperial and Soviet Russia, 437. Reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan.

Railways helped unleash the market driver, particularly in agriculture. Cheaper transportation increased labor mobility and stimulated grain exports, mainly through Odessa. In the middle of the century, only 2 percent of the Russian grain harvest was exported; by 1900 Russia was exporting almost 18 percent, and Russia had become one of the world's largest exporters of grain.34 Grain exports increased despite contemporary claims, echoed by many historians, that Russia was undergoing a serious agrarian crisis. There was indeed an agrarian crisis in the most densely populated central agrarian regions; but growth was more rapid outside the old core area of Muscovy, particularly in the Baltic provinces, western Siberia, and the Pontic steppes. In the late nineteenth century, Russian grain production grew as fast as in Germany, by three times. Only the USA exceeded this rate of growth. Between 1883 and 1901, Gregory argues that agricultural output grew at 2.55 percent per annum, which was twice the rate of population growth. Furthermore, population growth did not necessarily mean rural impoverishment. On the contrary, the 26 percent increase in total output of consumption goods per capita between 1887 and 1904 must reflect, at least in part, a rise in average rural consumption levels. One sign of such modest improvements in rural living standards is that the price of land rose, as did the wages of agricultural laborers.35

Railway building encouraged growth in the production of coal, iron, and manufactured goods. Between 1891 and 1901, as the length of the Russian railway network doubled, so did production of coal and oil, while the output of iron almost tripled. By some estimates, industrial production grew in the 1890s at the astonishing rate of 8 percent.36 In the late nineteenth century, hand power still dominated smaller manufacturers. But the number of steam engines increased in large enterprises such as the machine-building works of the capital, from c.6,400 in 1887 to 21,000 in 1908, while their total horsepower increased from 166,000 in 1887 to 1,230,000 in 1908. By 1908 steam power already accounted for 87 percent of industrial power consumption. However, even in the very largest plants most secondary operations were still carried out by hand.37

The revolutionary nature of these changes is perhaps most apparent in the Pontic steppes, the eastern part of modern Ukraine. By 1900, the Pontic steppes had witnessed all three of the dominant technologies of the Holocene era, beginning with pastoralism, which was in decline, followed by farming, which was on the rise, and ending with industrialization which was just beginning. In the nineteenth century, agricultural production increased rapidly on the region's rich black soils, turning the “wild field” of the Middle Ages into the bread basket of the Russian Empire. But parts of the Pontic steppes were also transformed into one of Russia's first modern industrial regions, because the steppes contained coal and metal ores as well as farmlands. The vast reserves of coal in the Donets basin (the Donbass) were first discovered in 1721, during the reign of Peter the Great. By 1795 Donbass coal was providing coking coal for an iron works at Lugansk.38 Coal production remained small scale until stimulated by the arrival of railways. Donets coal drove steam engines and railways, while its coke fueled iron and steel works that made rails and rolling stock using iron ore from the Krivoy Rog region near Kharkovsk. Railways built with Ukrainian iron and steel and driven by Ukrainian coal cheapened grain exports and, when coupled with the mining of coal and metal ores, helped turn Ukraine into a major industrial center.

In the 1870s, a Welsh engineer, John Hughes, established iron works in the Donbass to supply rails under government contract, and in 1885 a railway line was built linking the Donets to the iron ores of the Krivoy Rog. Yuzovka, the town Hughes founded, is modern Donetsk (Figure 10.5). Nikita Khrushchev would arrive in 1908 and spend much of his youth here, working as a miner. His biographer, William Taubman, describes the town's early history:

Figure 10.5 John Hughes's home in Yuzovka.

John Hughes's British technicians and Russian and Ukrainian workers erected a vast industrial complex, including mines, blast furnaces, rolling mills, metalworking factories, and repair and other workshops. In due course, railroad spurs extended to several mines in and around the town. By 1904 the population of Yuzovka and environs had climbed to forty thousand; by 1914 it had reached seventy thousand. The Donbas is an area the size of Vermont; in 1913 its mines produced 87 percent of Russia's coal.39

For immigrants like Khrushchev, Yuzovka epitomized the worst aspects of capitalism. English workers lived in a special “English colony,” with English cottages supplied with running water and electricity and built along tree-lined streets. Most Russian workers lived in bleak ghettos. One wrote: “the ground was black; so were the roads. Not a tree was to be seen near the mine, not even a bush; no pond, or even a stream. And beyond the mine, as far as the eye could see, only the monotonous, sunburned steppe.”40 Khrushchev's father, Sergei, had lived in workers’ barracks with 50–60 in a dormitory, sleeping on plank beds with ropes stretched across the room on which they could hang their clothing. The night shift slept in the beds left by the day shift. In the Yuzovka mines, workers got used to crawling through unsafe, waterlogged shafts that were so hot that some miners worked naked.41

By 1900, Ukraine had replaced the Urals as Russia's major iron-producing region. In the Pontic steppes, we see a new ecological imperialism, the mobilization, with the aid of modern industrial technologies and fossil fuels, of agricultural and industrial resources that had been unusable as long as the steppes were ruled by pastoral nomads. What had been colonial borderlands were now integral parts of the Russian mobilizational system.

In the late nineteenth century, market forces and independent entrepreneurial activity played as important a role in economic development as government policy. Foreign capital, foreign entrepreneurs such as John Hughes, and imported technologies were crucial to industrialization. In this respect, Ukraine's experience was very different from that of an older industrial region, the Urals, whose iron industry dated from the time of Peter the Great. In 1891, there was only one modern iron producer in the Urals, which operated in partnership with a French company, while in Ukraine, with many more foreign entrepreneurs, there were modern blast furnaces and rolling mills.42 Even most industrial research came from abroad, despite the increasingly impressive achievements of Russian scientists such as Mendeleev, who did important research on the chemistry and geology of oil in the 1880s. Before the twentieth century, there was little contact between Russian science and Russian industry.43

Foreign capital and expertise played a particularly crucial role in Russia's nascent oil industry. Near Baku, on the shores of the Caspian Sea, oil seeping to the surface had been used since ancient times. Marco Polo described how naphtha was exported on camels, and in 1636, the German traveler Olearius saw petroleum being sold as a medicine and a lamp fuel. Though conquered briefly in the 1790s, the Baku region came under permanent Russian control after the 1813 treaty with Persia. As early as 1825, there were 125 shallow wells in the Baku region, but none were more than 30 meters deep and most were both primitive and shallow. Oil was extracted with buckets or by soaking it in rags.44 Steam-powered drills appeared in the mid-1860s and the first gusher was produced at a depth of 45 meters in 1870. In 1870, the Russian government allowed foreign investors into the region. Many came, including Alfred Nobel in 1873. Oil was relatively cheap to produce in Baku because it lay near the surface, and, after a Rothschilds loan allowed the building of a pipeline to Batum on the Black Sea, it could be transported cheaply to European and American markets, where it was used at first in the form of kerosene for lighting. Cheap production and transportation allowed Russian producers to undercut American producers, so the industry attracted foreign investment and grew rapidly in the 1880s. The Nobel consortium was particularly important in Baku and Grozny.

However, by 1900 oil wells had to be dug deeper, and as oil prices fell and costs of extraction rose, Russian firms reacted defensively, not by investing in more modern equipment but by cutting production. This was more in the spirit of “direct mobilization” than capitalism. In the coal industry, too, Russian producers responded to the challenge of mining at greater depths by cutting production, forming a producers’ syndicate, Produgol, in 1902, and passing higher costs on to consumers.45 These reactions suggest that Russian traditions of monopolistic control over valuable resources still limited the effectiveness of the market driver.

These early attempts to manage Russia's energy resources capture some of the differences between the market driver of growth and traditional methods of direct mobilization which were extensive rather than intensive. Given abundant resources, both strategies of mobilization worked well, but the traditional driver was, for the most part, less innovative and more wasteful of energy, labor, resources, and land. Still, however it was done, the Russian Empire was beginning to learn how to mobilize its vast reserves of energy and raw materials. Figure 10.6 charting coal and oil production from 1859 to 1917 shows the increasing importance of fossil fuels in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Figure 10.6 Chart of coal and oil production, 1859–1917. Data from D'iakonova, Neft’ i ugol’ v energetike tsarskoi Rossii, 165–167.

Exports linked the Russian economy more closely to world markets, particularly for grain, timber, oil, and textiles. By 1914 Russian grain exports were second only to those of the USA. Integration into the global economy was helped by the government's decision to put the ruble on the gold standard in 1897, in order to secure international loans for industrial growth. So successful was this maneuver that by 1914, Russia was the world's largest debtor nation, which is surely a sign not of sluggish growth but of rapid integration into the world economy and the growing importance of market forces. Gregory writes:

On the eve of World War I, Russia was the world's largest debtor. Its currency was backed by gold; the gold ruble exchanged at a fixed and stable rate with the currencies of the other industrialized countries. The stocks and bonds of Russian corporations, state governments, and the imperial government traded actively in financial centers not only in Moscow and Saint Petersburg but also in London, Paris, and Amsterdam. The multinational companies of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – the Singer Company, Siemens, and Krupp – had branches in Russia. Although foreign companies operating in Russia complained about corruption and the difficulty of obtaining necessary government licenses, the commercial laws of Russia appeared to provide sufficient stability to attract direct investment into Russia.46

But early in the twentieth century there were clear limits to Russian economic growth. Particularly in agriculture, most growth was still extensive. Labor productivity grew sluggishly, both in agriculture and industry, and communal land tenure in the villages limited, though it did not entirely block, the commercialization of rural life. Furthermore, the government's share of the economy, at about 8–10 percent, was probably the highest of all developing countries. Nevertheless, while foreigners complained about the difficult and sometimes corrupt business environment, there was also emerging a body of Russian corporate law, and flourishing commodity and capital markets.47 Nor was the government's role in driving economic growth as important as many supposed. It was, after all, confined mostly to the railways, and the closely linked metallurgical and mining sectors.

In so far as prices were set primarily by markets rather than by governments, it makes sense to describe the late Tsarist economy as a market economy, and Russian society as a rapidly evolving capitalist society. Manufacturing output increased rapidly, particularly in the 1890s and in the years just before World War I, and the proletariat, though small, was growing fast. Lenin, who studied such things closely, noted that between 1866 and 1903 the number of factories with more than 16 workers rose from 2,500 to 9,000.48 But, like Russia's populists (including his own brother), Lenin believed firmly that when it came, a Russian revolution would be a working-class revolution of the peasantry and the urban working classes rather than a bourgeois revolution.49 Furthermore, as Lenin understood, the preservation of the commune did not prevent increasing market activity in the villages, as more and more peasants leased their allotments, hired family members out as wage laborers in cities or other rural areas, sold surplus grain, and, particularly near big cities, engaged in artisan activities. The German historian Oskar Anweiler described Russian workers in this period as “economic amphibians,” because they lived both in the traditional rural economy and in Russia's rapidly industrializing cities.50

Though still archaic in many areas, Russia's economy was firmly launched on the path towards industrialization, and the market driver was playing an increasingly important role, alongside the direct mobilization of modern technologies. In Gregory's summary:

During the last thirty years of the Russian empire, Russia's economic growth was more rapid than western Europe's, but its rapid population growth held per capita growth to the west European average. The structural changes that occurred in the thirty years preceding World War I were in line with the first thirty years of modern economic growth elsewhere. Russia definitely had begun the process of modern economic growth by the outbreak of World War I.51

In 1899, Sergei Witte's assessment was similar. He argued that Russia's economy was in a “state of transition to the capitalist system.”

The changes that have taken place in Russian life in the past thirty years have had a direct impact on the conditions of development of our industry and commerce. The emancipation of the peasants from serfdom and the ensuing deep penetration of commercial and monetary relations into rural life, the development of the railroad network and the spread of credit in a variety of forms, the movement of population within the Empire and the settlement of new and hitherto unpopulated borderlands in the south and east, the gradual outflow of manpower from the land to other trades, the growth of cities, and the formation of new industrial regions and centers – all of these circumstances have changed the economic system of the Empire so much that commercial-industrial activity, which once affected the interests of only certain classes of the population, has now embraced the whole country.52

POLITICAL CHANGE AND DECLINING ELITE UNITY

However, rapid economic growth was disruptive. It stirred up discontents at many different levels of society, and in the early twentieth century these discontents, poorly handled by an often incompetent government, would generate a serious revolutionary crisis. But, as Gregory notes, the 1905 and 1917 revolutions followed periods of rapid growth, so they are best understood as growth pains rather than as signs of chronic backwardness.53 That suggests that, as long as the Russian elite could maintain a degree of cohesion and unity, the mobilizational machine might have contained growing pressure from below as it had many times in the past. Yet economic and social change had also loosened ties within the ruling group, weakening traditional respect for autocracy and creating new elite groups with distinct interests and modern political views. Meeting these complex political and social challenges required strong, clear-sighted, and well-informed leadership. Unfortunately, Russia's last Tsar, Nicholas II, lacked the political skills of a Peter the Great. Unlike his father, Alexander III, he also failed to listen to his more skillful advisers, and the autocratic Tsarist political system lacked the mechanisms needed to advise him well or steer his policies. A weak and indecisive autocrat struggled to navigate the choppy waters of a rapidly modernizing society.

The Great Reforms loosened the ties that bound Russia's elite groups to the autocracy. Abolishing serfdom cut ancient bonds between the nobility and the autocracy, while newer entrants to Russia's upper classes often had education, commercial skills, influence, ambition, and ability, but fewer ties to autocracy than the traditional nobility. The historian P. N. Miliukov wrote in 1903:

What must be mentioned first is the enormous growth of the politically conscious social elements that make public opinion in Russia. The gentry still play a part among these elements, but are by far not the only social medium of public opinion, as they were before the emancipation of the peasants. Members of the ancient gentry are now found in all branches of public life: in the press, in public instruction, in the liberal professions, not to speak of the state service, and particularly the local self-government. But it would be impossible to say what is now the class opinion of the gentry. The fact is that the gentry are no longer a class; they are too much intermingled with other social elements in every position they occupy, including that of landed proprietors. By this ubiquity the gentry have added to the facilities for the general spread of public opinion; but as a class they influence public opinion in an even smaller measure than in former times.54

Russian liberalism and a modern revolutionary movement both emerged soon after the Great Reforms. Both traditions owed their radicalism to the growing importance of the intelligentsia, those within Russia's emerging professional classes who were educated enough to have strong views about government and society, but lacked the traditional privileges that might have bound them to autocracy. The intelligentsia included both déclassé nobles and educated non-nobles, whether lawyers, teachers, doctors, veterinarians, statisticians, or agronomists. Many were hired as experts by the zemstva, and some were radicalized by working amongst the peasantry, particularly after the massive famine of 1891. According to one very rough estimate, the size of Russia's emerging professional classes – those earning wages through brain work – increased from about 50,000 in 1850 to about 400,000 by 1900. Russia's entrepreneurial classes also increased, turning the Muscovite merchantry into something like a modern “bourgeoisie.” In 1850, c.246,000 were officially registered as merchants; by 1900 there were 600,000, but there were many more petty traders and entrepreneurs, most of peasant origin.55

Russian liberals came, for the most part, from the upper and more educated sectors of the nobility. By the 1890s many “zemstvo liberals” had begun to argue for a national consultative assembly or Duma that could easily be established by forming a national equivalent of the provincial zemstvo, created in 1864. In 1895, moderate liberals asked the new Tsar, Nicholas II (1894–1917), to create such an elected advisory body. In an early sign of the political rigidity that would lead to his downfall, Nicholas dismissed the proposal as a “senseless dream.” In response, even conservative liberals began organizing a series of national zemstvo congresses to discuss possibilities for moderate political reform.

The Russian revolutionary movement also emerged from within Russia's elites, and many of its members shared the traditional elite commitment to unity and discipline, though they also shared the egalitarian goals and the revolutionary élan of the European revolutionary movement. However, its members were generally younger and many were students. The Russian revolutionary movement's distinctive combination of emancipatory goals and a commitment to party discipline is apparent from one of its earliest manifestos, “Young Russia,” which appeared in 1862:

Society is at present divided into two groups, which are hostile to one another because their interests are diametrically opposed … The party that is oppressed by all and humiliated by all is the party of the common people. Over it stands a small group of contented and happy men. They are the landowners … the merchants … the government officials – in short, all those who possess property, either inherited or acquired. At their head stands the tsar. They cannot exist without him, nor he without them. If either falls the other will be destroyed … There is only one way out of this oppressive and terrible situation which is destroying contemporary man, and that is revolution – bloody and merciless revolution – a revolution that must radically change all the foundations of contemporary society without exception and destroy the supporters of the present regime.56

In the 1860s and early 1870s most Russian revolutionaries were “populists.” They had, as yet, little understanding of capitalism or industrialization, and their goal was to liberate the peasantry and create an egalitarian peasant-dominated socialist republic. By the late 1870s, small numbers of populist revolutionaries were forming tight-knit revolutionary groups whose aim was to assassinate Tsar Alexander II. In 1881, one of these groups, Narodnaya Volya, or “The People's Will,” succeeded. In 1887, another group that included Lenin's elder brother, Sasha Ulyanov, was arrested for plotting to assassinate his successor, Alexander III. Its leaders were all executed.

A Russian Marxist movement emerged in the 1880s. Unlike the populists, the Marxists (who would soon include Sasha Ulyanov's younger brother, the young Lenin) did understand the transformative nature of capitalist industrialization. They insisted that Russia, like Europe, would pass through a capitalist phase of rapid growth and accelerating class conflict before building a socialism in which industrial workers, the proletariat, would be the main beneficiaries and the dominant class. No revolutionary group gained broad popular support before the twentieth century. Both Marxists and populists eventually split over the issue of whether to build a broad-based popular movement or to concentrate, instead, on disciplined conspiratorial action to overthrow the existing system.

Russia's conservatives, such as the royal tutor Konstantin Pobedonostsev, argued that the government had already made too many concessions to modernity. Now it was necessary once more to support the autocracy and Russian tradition. To rally this constituency, the government of Alexander III launched aggressive policies of Russification, suppressed regional nationalisms, and supported virulent and sometimes murderous forms of anti-Semitism. Somewhere in the middle of these conflicts were the many nobles and officials committed, like Sergei Witte, to a Russian version of the Meiji reforms in Japan: a rapid transition towards industrialization, presided over by a strong government capable of maintaining stability while developing industry and commerce.

DESTABILIZATION AND RESTABILIZATION: 1900–1914

Between 1900 and 1914, the strains of rapid economic and social change brought the Russian mobilizational machine close to collapse.

1900–1906: TEMPORARY BREAKDOWN

The Great Reforms were followed by three decades of relative social calm, despite the emergence of a revolutionary movement and the massive famine of 1891. From the end of the 1890s, popular protests began to increase in both rural and urban areas. During the global slump of 1900, employers fired workers and cut wages, particularly in the metal industries where growth had been most rapid in the 1890s. Industrial production, which had grown at 8 percent per annum in the 1890s, slowed to 1.4 percent per annum between 1900 and 1906.57 Troops were used to suppress strikes 19 times in 1893, 50 times in 1899, and over 500 times in 1902.58 The government suppressed strikes with force, and refused to legalize strikes or unions. This guaranteed that when strikes did occur, they would be violent. The government's one attempt to handle industrial protest with more finesse was a fiasco. Between 1901 and 1903, under a plan proposed by a police official, S. V. Zubatov, it organized official unions. Zubatov wrote:

An autocracy should keep above the classes and apply the principle of “divide and rule.” … We must create a counter-poison or antidote to the bourgeoisie, which is growing arrogant. Accordingly, we must bring the workers over to us, and so kill two birds with one stone: check the upsurge of the bourgeoisie and deprive the revolutionaries of their troops.59

In practice, the Zubatov unions provided government-sponsored training for would-be strikers and unionists. In 1903, Zubatov unions organized strikes in the oilfields of Baku and the industrial regions of Ukraine. Zubatov was sacked.

In rural areas, population growth exacerbated old resentments over land shortage and high taxation, particularly after the famine of 1891. The 1900 slump hurt peasants, because many relied on casual wage-labor and income from domestic industries. In 1902 rural protests broke out in the Ukrainian provinces of Kharkov and Poltava. By 1904, they had spread to most provinces west of the Urals. Rural communes, which the government still thought of as bastions of order, helped organize many protests. Riots often began with communal gatherings at which migrant workers brought news of protests in other regions. From commune meetings, groups of peasants, sometimes armed with pitchforks and clubs, would attack local government offices and destroy tax records, or burn the mansions of their landlords. By 1905, much of the countryside was in revolt.

Within Russia's upper classes, dissidence began to assume more organized forms. In 1902, the historian P. N. Miliukov and an ex-Marxist, P. B. Struve, founded an underground paper called Liberation to advocate for a constitutional government. In January 1904 a “Union of Liberation” was formed in St. Petersburg. It demanded an end to autocracy and an elected assembly with real legislative power. Support for “Liberation” came mainly from the non-noble educated and entrepreneurial classes. By 1905, liberalism of some kind was widespread within elite groups. But many of the goals of Russian liberalism were also shared by more radical oppositional groups, many of which saw liberal political reforms as a first step towards revolution. In 1900, a group of Russian Marxists, including Lenin and Martov, founded an illegal Social Democratic paper, Iskra, or “The Spark.” In 1903 the same group organized the first Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Party. The founding Congress of the party (technically its second Congress) was organized in Brussels in 1903, then moved to London after its members were expelled from Belgium, probably under Russian pressure. During the Congress the party split into a Bolshevik wing, led by Lenin, which stressed party discipline and unity and the importance of a popular uprising, and a Menshevik wing, headed by Martov, which was committed to building a broader popular movement. In 1901, populist groups formed a Socialist Revolutionary Party under the leadership of Victor Chernov (1873–1952).

Cutting across and sometimes intertwined with the pressures of economic change were those of ethnic conflict within an increasingly diverse empire in which official Russification had provoked local nationalisms. Though they originated among the small intelligentsia class, these nationalisms could prove powerful and dangerous if they managed to attract support from the much larger peasant classes in rural areas. Regional nationalisms were particularly developed in areas such as Poland, which had old national traditions. Ukrainian nationalism emerged in the nineteenth century, drawing inspiration from the historical traditions of Kievan Rus’ and Lithuania.60 The works of the great historian Kostomarov and the poet Taras Shevchenko created a powerful historiographical and literary tradition around which a modern sense of national identity would be forged within Ukraine's small intelligentsia. Government attempts to suppress Ukrainian-language writing and scholarship ensured that Ukrainian nationalism would become a significant force within the intelligentsia. In 1897 there appeared a moderate Ukrainian nationalist organization, the General Ukrainian Organization, and in 1900 a revolutionary organization, the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party. Though its roots lay within the Ukrainian intelligentsia, Ukrainian nationalism would prove powerful because, during the revolutionary crises of the early twentieth century, it would attract significant peasant support as well. Nationalist movements also appeared in the Caucasus, the Baltic provinces, and in Central Asia (on which, see Chapter 11). In Georgia, a region with strong national traditions and an ancient national history, Mensheviks found themselves at the head of a national movement that proved particularly powerful because it attracted significant peasant support. Though the key events of the 1905 revolution took place in the Russian heartland, protests in the peripheries destabilized and unnerved the government, and stretched its military resources.61

Given the many divisions between its opponents, the Russian government should have been able to cope with the simmering discontent inevitable in a rapidly industrializing society. But the deep humiliation of failure in the Russo-Japanese War, which began in January 1904, helped unite the government's opponents, turning serious difficulties into a potentially fatal crisis. In the major cities, each military defeat sparked new storms of protest during 1904. What finally united the various opposition groups was the Tsar's decision to use force against a peaceful workers’ demonstration in St. Petersburg on January 9, 1905. Ironically, the 100,000 or more workers who demonstrated for better working conditions were led by a priest, Father Gapon, who ran a union organized, like the Zubatov unions, under state auspices. The demonstrators’ petition reflected the rhetoric police officials thought appropriate on such occasions, but also showed the extent to which liberal slogans were beginning to link different oppositional movements.

We working men of St. Petersburg, our wives and children, and our parents, helpless aged men and women, have come to you, our ruler, in quest of justice and protection. … The bureaucracy of the government has ruined the country, involved it in a shameful war and is leading Russia nearer and nearer to utter ruin. We, the Russian workers and people, have no voice at all in the expenditure of the huge sums collected in taxes from the impoverished population. We do not even know how our money is spent. The people are deprived of any right to discuss taxes and their expenditure. The workers have no right to organize their own labour unions for the defence of their own interests. … The people must be represented in the control of their country's affairs. Only the people themselves know their own needs.62

Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstration and its protestations of loyalty, Nicholas ordered the police to disperse the protesters with gunfire and sabers. The police estimated that 130 were killed and 450 wounded. Others put the casualties much higher. All opposition groups now united behind the anti-autocratic program of the liberals. Demonstrations broke out in all major cities. They were supported by workers, intellectuals, and even, on occasion, by government officials. In May, professional associations formed a “Union of Unions.” In the industrial town of Ivanovo, an industrial strike committee modeled on Russia's traditional village communes constituted itself as a “Soviet” or “Council” of all workers. Soviets soon sprang up throughout the country. A St. Petersburg Soviet was formed on October 14 under the leadership of a young Marxist revolutionary, Leon Trotsky (1879–1940). Soon, other Soviets looked to it for leadership. Ominously for the government, military discipline began to break down. In May, there was a mutiny near Tashkent; in June, a mutiny on the battleship Potemkin in Odessa harbor.

In August 1905, the government made its first significant concession by offering to create a purely consultative elected body. By now, all but the most conservative liberals found such an offer insulting. On September 19, printers went on strike and workers in the two capitals followed suit. On October 7, railway workers stopped work, which prevented the movement of troops, most of whom were still in the Far East. Russia faced the first general strike in its history. Even bank workers and officials of the central ministries stopped work.

In desperation, Nicholas II turned to his former Finance Minister, Serge Witte, for advice. Witte had returned from the USA after negotiating surprisingly favorable peace terms with Japan at the treaty of Portsmouth. Witte persuaded Nicholas to back down. On October 17, in what would become a characteristic pattern of stubborn resistance followed by humiliating backdowns, Nicholas issued the “October Manifesto.” The document promised to grant basic civil liberties and establish an elected State Duma that would share legislative authority with the Tsar. This was a change of colossal significance and many protesters were delighted. It seemed to have replaced Russia's traditional autocracy with a constitutional government.

The October Manifesto split the large but fractured anti-Tsarist coalition. Conservative liberals formed an “Octobrist” party representing those willing to accept the Tsar's concessions. But most liberals demanded more. In October, they formed the “Kadet” (Constitutional Democratic) party, with Miliukov as one of its leaders. The Kadets, though dissatisfied with the October Manifesto, insisted on ending the general strike and all revolutionary activity. The October Manifesto seemed to be rallying elite groups around a reformed monarchy.

But popular protests continued. The Petrograd Soviet demanded further concessions to labor, and peasant insurrections peaked in November and December. In Tashkent, troops fired on a crowd of demonstrators immediately after the publication of the October Manifesto. Then discipline collapsed within the army. Many rank-and-file soldiers stopped obeying orders in the naïve belief that the October Manifesto had abolished existing structures of authority even within the army. Between October and the end of the year, there were mutinies in one third of all military units in European Russia, while mutinies along the Trans-Siberian railway prevented the return of troops from the East. In November, the government lost control of 10 major towns, including Moscow.

Despite the many danger signs, it turned out that divisions within the revolutionary coalition had given the government just enough leverage to survive. Having secured the half-hearted support of leading intellectuals, industrialists, officials, and military leaders, the government began to look more stable, and that persuaded many mutinous soldiers to return to barracks. The government offered soldiers improved pay and conditions, and on December 3, it used the army to arrest all 260 members of the St. Petersburg Soviet. Two weeks later, it used units that had mutinied just a few weeks earlier to suppress a working-class insurrection in Moscow. In the same month, troops began to suppress disorders in the Baltic States, Poland, the Caucasus, Siberia, and Central Asia. Early in 1906, the army began to crush disturbances in the countryside, making free use of martial law and the death penalty as it did so. Between 1905 and 1909, the government would execute almost 2,400 people on charges of terrorism; revolutionaries retaliated with at least as many assassinations.63 In early 1906, the return of troops from Manchuria and a French loan negotiated by Witte helped stabilize the government. In May, just after Witte had negotiated the French loan, Nicholas dismissed him.

As the government regained its balance, Nicholas began whittling away the promises he had made in October 1905. He insisted, first, that the government alone would draft the new constitution, the so-called “Fundamental Laws.” These were published just before the First Duma met in April 1906. The Fundamental Laws established a two-house parliament. The Duma, the lower house, was elected in separate class curia, in which the vote was weighted differently for different classes. In the upper house, the State Council, half of the members were to be appointed by the emperor, while the other half were to be elected by institutions such as the zemstva, the Academy of Sciences, and the clergy. On the all-important matter of the government's essential nature, the laws were contradictory and ambiguous. The Fundamental Laws declared that “Supreme, autocratic power” belonged to the emperor. Yet they also declared that no law could come into force without the consent of both houses of parliament. The emperor retained the right to appoint government ministers at his discretion, and the Duma received limited powers to question the government budget. Article 87 allowed the government to issue laws by decree when the parliament was not in session, though it was required to have them ratified at the next parliamentary sitting.