[11]

1750–1900: BEYOND THE HEARTLANDS: INNER EURASIAN EMPIRES, RUSSIAN AND CHINESE

INTRODUCTION

Seen from Khuriye (modern Ulaanbaatar) or Bukhara, Kashgar or Yakutsk, Orenburg or Semipalatinsk, the history of the century and a half before 1900 was dominated not by industrialization and fossil fuels, but by the shifting balance of power between Inner Eurasia's two hegemonic powers, as the Russian Empire conquered Central Asia and started nibbling at China's traditional spheres of interest in Mongolia and the Far East.1

The area controlled by the Russian Empire increased from about 15 million sq. kilometers in 1750 to 18.2 sq. kilometers in 1858. By 1904, after Russia had conquered Transoxiana and temporarily occupied Manchuria, its empire controlled about 22 million sq. kilometers.2 It now included most of Inner Eurasia, and in Poland in the far west it had overflowed into Outer Eurasia. This was the empire's maximum extent, as defeat in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 would drive Russia out of Manchuria.3

It is striking that Russian expansion ground to a halt after filling most of Inner Eurasia. Indeed, this is one of the most powerful reasons for taking the idea of Inner Eurasia seriously as a unit of world history.4 Like the Mongol Empire and the Soviet Empire, the Russian Empire overlapped those borders, but only briefly, except in eastern Europe, which was, topographically, part of the great Inner Eurasian flatlands. The Soviet Union never directly controlled as large an area as the Russian Empire in 1900, but its informal empire was much larger, as it also dominated Mongolia, Xinjiang (before 1949), and most of eastern Europe (after 1945).

This chapter will consider Russian expansion in central Inner Eurasia, in the Kazakh steppe, and Transoxiana (western Central Asia). Then it will travel east, describing Russia's consolidation of control over the neo-Europe of Siberia, and its eventual advances into the Far East, Manchuria, and even Alaska. Finally, it will discuss Mongolia and Xinjiang (eastern Central Asia), regions that had fallen within China's Inner Eurasian empire but were beginning to slip from China's grip.

THE CHANGING NATURE OF RUSSIAN EMPIRE BUILDING

Before the mid-nineteenth century, Russian expansion was pragmatic, non-ideological, and driven largely by commercial, military, and strategic concerns. Russian rulers and officials treated ethnic and cultural differences primarily as administrative or fiscal challenges. Loyalty and religious affiliation seemed more important than ethnicity, and Muscovite and Russian governments had generally managed to co-opt regional leaders. After the conquest of Kazan’, for example, Tatar nobles had been allowed to retain their land and religious practices as long as they swore allegiance to the Tsar. Not until the eighteenth century did Russian Tsars, beginning with Peter, start demanding conversion to Orthodoxy in return for landownership.

In the nineteenth century, the ideological tone of Russian expansion changed, as the government developed a new and increasingly strident sense of imperial mission. Empire building by Russia's European rivals and new forms of nationalism gave an ideological edge to Russian expansion, and from the time of Nicholas I, Russian leaders and officials became more self-conscious about national and ethnic differences.5 In his Siberian reforms of 1822, Mikhail Speranskii began the practice of describing the empire's Asian subjects as inorodtsy, or “aliens.” After the Polish uprising of 1863, Russian governments begin to actively support the “Russification” of non-Russian regions, particularly in Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, and the Baltic provinces, where cultural and linguistic differences were smallest but, perhaps for that very reason, most threatening to Imperial cohesion.6 In regions such as Central Asia, where cultural differences were greater, Russian soldiers and officials took on many of the attitudes and methods of British India. They thought of Central Asia as a conquered colony with alien traditions.7

These shifts in Imperial attitudes would shape many aspects of Russian expansion in the nineteenth century. And they would shape how the empire's non-Orthodox populations responded to Russia's growing power. Adapting to the military, political, and commercial realities of Russian power was no longer quite enough. Local communities and their leaders had to develop counter-ideologies. These usually began with the defense of religious and cultural traditions, but eventually they would plant the seeds of new counter-nationalisms that would blossom only in the twentieth century.

THE KAZAKH STEPPES

The Russian Empire expanded into the Kazakh steppes using the same methods it had used in the Pontic steppes and the Urals.

During the eighteenth century, the three Kazakh Hordes had already accepted a loose Russian suzerainty. But it would take a long time to integrate them more fully within the Russian Empire. As in Siberia, the Pontic steppes, and the Bashkir and Kalmyk lands, expansion into the Kazakh steppes was less a matter of pitched battles than of a slow constriction of pastoralist lifeways through fort building, trade, and the planned and unplanned migration of peasant farmers from the Russian heartlands. Kazakh leaders and communities found their pasturelands shrinking, and their political and commercial options narrowing. In the Kazakh steppes, even more than in the Pontic steppes, Russian officials whose declared aims were defensive ended up playing the more aggressive role of boa constrictor.

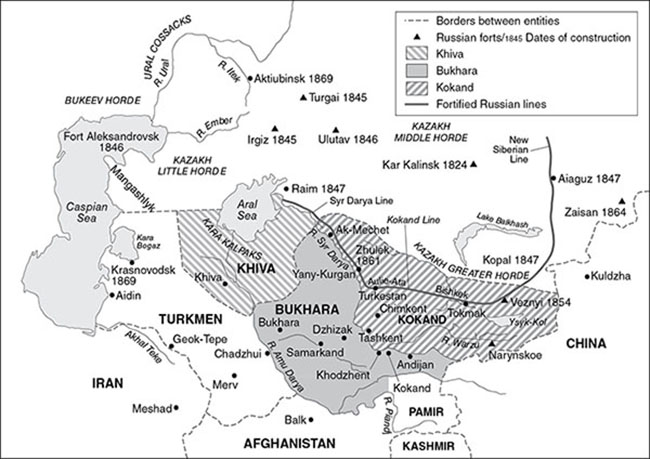

By the late eighteenth century, Russian fortified lines formed a huge loop that hemmed the Kazakh in on the western, northern, and eastern borders of their traditional pasturelands. Forts extended from Semipalatinsk in modern Kazakhstan (modern Semei, the site of many Soviet nuclear tests) northwards along the Irtysh river, west along the southern borders of Siberia to Omsk, and south to Uralsk in the Urals, then to Orsk and the Caspian Sea (see Map 11.1).

Map 11.1 Russian conquest of Central Asia. Rywkin, Russian Colonial Expansion to 1917, 209.

The destruction of the Zunghar Empire in 1750 had relieved pressure on the Great Horde's eastern borderlands. But Chinese control of Xinjiang created new frontiers and new pressures. In the early nineteenth century, the Great Horde faced a new imperial power, the Kokand khanate, which expanded north from Tashkent. These pressures explain why so many Kazakh leaders would come to see Russia as a potential protector.

Russian encirclement threatened traditional lifeways in many insidious ways. Winter camps or kstau were vital for traditional pastoralists, and their loss to forts or peasant immigrants could be ruinous. Groups of 20 to 30 households (auls) normally settled at winter camps for four or five months, so the sites had to be well sheltered, with good water and grazing. During summer migrations, poorer or older people were often left at the kstau to grow grain or gather hay.8 In spring most Kazakh set off to summer pastures or dzhailau, and auls broke into smaller groups, each of which might move several times during the summer. In the fall, the auls regathered at their winter camps. Some migrations extended over hundreds of kilometers, and required meticulous organization and the use of small advance guards.9

Shrinking pasturelands forced all but the wealthy to keep fewer horses (the animals with greatest prestige and military value), and to rely more on cattle, sheep, and goats. Sheep were particularly important because they were tough, could survive poor pastures and cold weather, and could be sold at the markets of Khiva, Bukhara, Kokand, or Orenburg. Those without enough livestock to live from herding hired their services to wealthier pastoralists, or looked for work in nearby towns or as agricultural laborers.10

Russia could tempt as well as strangle. Trade with Russia offered Kazakh khans prestige and wealth, and increased their room for maneuver. But trade was increasingly controlled by Russia and its forts, which quickly turned into steppeland commercial entrepots. Informally, Muscovite and Tatar merchants had traded across the steppes for centuries, but formal trade, with government backing, began in 1739 when the Russian government first allowed Russian traders to export precious metals to China and Central Asia.11 For much of the eighteenth century, Orenburg and Semipalatinsk were the major Russian bases for trade through the Kazakh steppe. From these and other steppe towns, huge caravans set out, each with several hundred wagons, protected by Kazakh guards.

There were annual or biannual caravans from Orenburg and Orsk to Bukhara, a journey of two to three months. On their return journeys they mainly carried cotton, as did Khivan caravans to Orenburg and Astrakhan. Three caravans left each year from Petropavlovsk to Tashkent, and two from Troitsk, on the Orenburg line, returning with fruits, rugs, silks, and craft goods.12 In the eighteenth century, Tatar merchants from the Kazan region, often working in partnership with Russian merchants, gained control of the trade routes through Kazakhstan that had earlier been dominated by “Bukharans.” The Russian government supported and protected Tatar merchants, because markets in the Central Asian khanates were closed to Christians.

Russia valued the Kazakh trade because many Russian industrial goods could not compete on European markets. By 1840, even before the conquest of Transoxiana, 37 percent of Russian exports traveled through the Kazakh steppes to Central Asia.13 Most steppeland trade was conducted through barter, but opportunities for arbitrage could make it very profitable. At the end of the eighteenth century it was possible to buy an iron kettle in Siberia for the equivalent of 2.50 rubles and exchange it in the Kazakh steppes for furs worth 50 rubles on foreign or Russian markets.14

Kazakh khans faced complex and bewildering choices as they responded to Russian, Chinese, and eventually Kokandi pressure. In the early nineteenth century, the Russian government eventually abolished the traditional khanates. In 1822, it removed the khan of the Middle Horde and placed his lands under Russian administration. In 1824, it also abolished the position of khan of the Small Horde, and began to govern much of the Kazakh steppe through regional sultans, tribes, and auls.15

The Great Horde preserved its independence slightly longer. The Qing conquest of Zungharia created new borders that crossed ancient migration routes, forcing many in the Great Horde to choose between Russian and Chinese overlords. In the early nineteenth century, the Kokand khanate expanded north into the Tashkent steppes, forcing those on the Russian side of the border to choose either Russian or Kokandi suzerainty.16 The Great Horde was finally conquered in the 1830s and 1840s after the failure of a major uprising in the Middle Horde, the Kenisary revolt. This lasted from 1837–1846 and was directed against both Russian and Kokandi encroachment. Its leader, Kenisary, noted sadly the absence of Kazakh unity.

The Russians come from the North, Kokand from the South. Having established fortifications, they trample us, from whom we have both this squeezing and this crowding, We, the children of the Kazakhs, What would we be if we had unity? Until now we have been split because we have no unity.17

Kenisary was the grandson of Khan Ablai of the Middle Horde, who had sought Chinese protection in the late eighteenth century. Today, Kenisary is regarded as the first great Kazakh nationalist. After defeating the Kenisary revolt, Russia built new fortified lines to the east of the Kazakh steppes and along the Syr Darya. These would eventually provide the launchpad for Russia's invasion of Transoxiana after 1865.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the Russian Empire had absorbed the Kazakh steppes militarily and administratively. Their cultural integration into the empire began with the emergence of a Russified Kazakh elite, mostly consisting of the children of Kazakh nobles educated in Russian schools. The absence of madrasas and established traditions of Islamic learning in the steppes made it easier for the Kazakh elite than those of Transoxiana to accept secular education.18 This was the milieu from which early Kazakh nationalists such as Choqan Valikhanov would appear. Valikhanov was the first to write down the great Kyrgyz epic poem Manas, which he described as the Iliad of the Central Asian steppes.

The ecological incorporation of the Kazakh steppes would largely be the work of peasant migrants, who followed Russia's soldiers and fort builders, attracted by military protection and the prospect of cheap, unfarmed land. The government made some attempts to limit migration, but many officials saw migration as a way of coping with growing land hunger in the heartlands. From the 1870s, the government began to encourage migration, and by 1914 about half the population of Kazakhstan and Semirechie had come from Russia, mostly illegally.19 The government supported colonization by planting settlements along post roads, while private entrepreneurs sent out khodoks or land scouts who leased plots from local Kazakhs and made them available to settlers. Settlers built farmsteads consisting mostly of earthen huts. Some paid local Kazakh for their land, and even worked farmland for them. Settler populations increased, and villages and small townships began to appear, until eventually the settlers were numerous and powerful enough to ask Russian officials for legal title to the lands they had once leased. The steppes were slipping from the grasp of Kazakh pastoralists.20

Despite government restrictions on migration, land hunger in Russia's central provinces and the 1890–1891 famine ensured that illegal settlement would continue. In Akmolinsk oblast’ in 1890, 9,000 would-be settlers arrived, doubling the number of settlers already in the region. A contemporary reported that:

settlers literally inundated all the Cossack and peasant settlements. Whole crowds of them roamed aimlessly about, spending their last means, seeking any kind of work … in such numbers that the situation became impossible. Lured by the letters of relatives about the abundance of the steppe lands, as if they were freely given out for settlement, and deceived in their bright hopes, … the spirits of the newly arrived naturally fall, and their helplessness makes a depressing sight.21

After the creation of the Resettlement Administration in 1896, the government supported colonization more actively, particularly near the Trans-Siberian railroad. Officials envisaged huge irrigation projects in the steppes that would support large populations of both Russians and Kazakhs, and create rich agricultural surpluses.22 Similar schemes would be introduced 60 years later under the Soviet Virgin Lands program.

Peasant migrations undermined traditional lifeways. Settler villages often cut traditional migration routes, or encroached on traditional winter camp sites, so many pastoralists had to find new niches in a rapidly changing world.

Some nomads cut hay for winter fodder and built winter shelters for a portion of their animals. Some began to spend their winters in dwellings of wood, sod, or mud, depending on the house styles of their nearest neighbors, or to put up a clay wall around their encampment of yurts. Deprived of their richest pastures, many Kazaks were forced to give up pastoralism partially or completely. Some who lived near lakes or rivers took up fishing. … Some settled at the edge of Russian colonies and eventually became a part of the settled community. Others hired out as mine workers or as agricultural laborers at harvest time. … At the Spassky mines, many of the Kazak employees were young men who worked only long enough to earn a bride price, then returned to the aul.23

As more Kazakhs took up farming, the government raised its estimates of the amount of “free” land available for settlement. A commission dispatched in 1895 and headed by the statistician F. A. Shcherbina concluded that the newly established farmlands were:

a historically necessary symbol of change from one form of economy to another. … Replacing the nomad with his eternally wandering herds there has arisen here a half-settled form of life and occupation with the land. And where the plow has cut into the bosom of the earth pastoralism has already started to break up and an agricultural way of life has begun.24

Nomadic lifeways that had survived for thousands of years were beginning to vanish.

TRANSOXIANA

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the only major region of central Inner Eurasia beyond Russia's direct control was Transoxiana. Here, in contrast to the steppes, there were powerful regional polities with their own armies, so conquest took the form of major military campaigns.

THE KHANATES

In the late eighteenth century, Transoxiana was still ruled by the three khanates that had emerged in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Bukhara, the richest and most populous, had about 3 million people; Khiva, the most compact, had about half a million; and Kokand had a population of about 1.5 million.25

The khanates ruled populations that were extraordinarily diverse, and this made it impossible to create a strong sense of ethnic cohesion even at the regional level.26 The khanates included pastoralists and farmers, Turkic and Persian speakers, tribes that identified as Turkmen or Uzbek or Tajik or Kyrgyz, and large slave populations, mostly of Persian or Russian origin. Most slaves worked in agriculture, though some rose high in the administration of the khanates. Those without a clear role or place in this patchwork world were usually poor. Many herded a few livestock, but not enough to make a living. In the middle of the nineteenth century, perhaps a quarter of Bukhara's population was indigent.27

But though many moved between the cities and the steppes, the most fundamental difference was still between the oases and the steppes, between farmers and pastoralists. The oases had stronger legal and educational traditions, well-educated clergy, wealthy merchants, and complex, if ramshackle, state structures. Between the cities, there were still large nomadic populations, kinship trumped bureaucracy, and religious traditions were still shamanic in their rituals and theology.28

Even in the steppes there was great political and cultural diversity. The Kazakh had khans, though their authority was limited, even in times of war. The Kyrgyz, who had been driven south by the Oirat in the seventeenth century and nomadized in eastern Transoxiana, the Kashgar region, and Semirechie, did not normally have overall khans, but could mobilize rapidly for war or raiding under temporary leaders known in the nineteenth century as manap. To allow for rapid mobilization, many Kyrgyz nomadized in large tribal groups, whose campsites were huge, sometimes stretching over 20 kilometers along rivers or mountain ridges. They often included several hundred families under the authority of a local leader or “beg,” who could form them into an army in just a few hours.29 In Turkmenistan, social structures were exceptionally egalitarian, and overall leaders, khans or serdars, were chosen only during major wars.

Transoxiana's rulers enjoyed only thin reserves of loyalty and legitimacy as they juggled these centrifugal forces. This meant that the power and wealth of individual rulers varied greatly, and depended to an exceptional degree on their personal skills. Chinggisid descent still mattered in both the cities and the steppes, but so, too, did a reputation for justice and Islamic piety.30 But the main challenge for the region's khans and emirs was to maintain control over both subordinate cities and regional steppe leaders and their armies. This was a messy, weak, and unstable version of the traditional smychka.

Methods of rule had changed little since the Timurid era.31 In the khanate of Bukhara, for example, the main provinces (vilayets) were ruled by governors known as hakim or beg, but military power depended on the support of tribal leaders. Below the vilayet was the tumen, and below that, the kent, the township or village. In the villages the dominant figures were the aksakals or elders. The primary function of all levels of government was the collection of taxes, most of which were levied on commerce or on land. But as few officials received salaries, there was an extra level of taxes, levied and assessed informally to pay the large and growing bureaucracy. Land taxes were crucial because, despite the importance of trade to the region's cities, irrigation agriculture still generated most of the region's wealth and food. Though some cotton and silk were grown, most crops were produced for subsistence or local trade. They included wheat, rice, and other grains, as well as garden produce such as melons and orchard fruits.32

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, all three khanates undertook modest reforms, mostly to improve their armies. Khiva and Kokand began to form standing infantry armies equipped with some modern weaponry, and Bukhara would begin forming its own standing armies under Emir Nasrallah from the 1820s.33 But tribal armies retained their importance in the military affairs and politics of all the khanates.

Late in the eighteenth century, the Bukharan and Khorezmian khanates both acquired new dynasties of Uzbek origin. In Bukhara, the Mangit dynasty, founded in 1753, ruled effectively from the accession of Emir Shah Murad (1785–1800). Shah Murad was a son-in-law of the last khan and a non-Chinggisid. He ruled, therefore, as an “emir,” which forced him and his successors into closer dependence on Islam. Shah Murad belonged to the Naqshbandiyya, and assumed the Arab title of amir al-mu'minin, the traditional title of the caliphs.34 Such titles provided an important counter-balance to the immense spiritual authority of the Bukharan ulama, which was magnified by their control of waqf foundations and their immunity from most taxes.35 The Bukharan emirate was known to its own people as Mawarannahr, Turan, or simply Buhara.36

In the 1830s, Emir Nasrallah (r. 1827–1860) enhanced the military power of the emirate by recruiting a standing army from farmers, townspeople, and Iranian or Kalmyk slaves.37 His forceful rule earned him the epithet of “the Butcher Emir” among his own subjects, and equal notoriety among the British for his execution of two British officers.38 But even Nasrallah failed to control outlying provinces. It took him 25 years to control Timur's homeland of Shahr-i-Sabz, and the more mountainous regions in eastern Bukhara were ruled by local “beks,” who obeyed the emirs of Bukhara in name alone.39 Nevertheless, Bukhara was more successful than either of the two other Central Asian khanates in building centralized military and political structures.

In Khorezm/Khiva, the Qongrat dynasty was founded in 1804 by Eltüzer Inaq, who assumed the title of khan despite not being a Chinggisid. Eltüzer's younger brother and successor, Muhammad Rahim (1806–1825), rebuilt the region's irrigation system, asserted his authority over neighboring Uzbek tribes, and launched booty raids against Turkmen tribes to the east and south, against Kazakh tribes to the north, and even against Persia and Bukhara.40 In 1839, Khiva defeated a Russian military expedition to the region. But the khan's power depended on his ability to negotiate with the pastoralist leaders who provided most of his troops. This meant that, like the princes of fourteenth-century Muscovy, he could never be sure which troops would turn up for military campaigns, or which side they would fight on.41

In the Ferghana valley, one of the most densely populated regions of Central Asia, a revived Kokandi khanate emerged in 1798, under the Ming dynasty, which had ruled in the region since the early eighteenth century. Kokand benefited most from the Qing defeat of the Zunghar Empire, which removed a dangerous neighbor and enriched Kokandi traders by expanding trade with the Tarim basin and China. In 1800 Kokand's ruler, Alim (1798–1810), assumed the title of khan, despite not being a Chinggisid.42 Buoyed by trade and military reforms, extensive investment in new irrigation systems and the production of cotton and silk, a series of skillful rulers supported expansion to the north towards Tashkent and the Kyrgyz steppes, southwards towards Badakshan, and eastwards into the Tarim basin. Alim's predecessor, Narbota Biy (c.1770–1798), had begun building forts in Kyrgyz lands, and used them to tax local tribes, to control migration and trade routes, and to manage lucrative trades in slaves and opium.43 Under Alim's rule and that of his son and grandson, Kokand conquered Tashkent and regions as far east as Bishkek, which it founded as a fort in 1825. Under Madali Khan (1822–1842), Kokand reached its largest extent and in 1826, an agreement with China gave Kokand partial suzerainty over Kashgaria (see below, p. 301).

However, military success was not matched by the building of durable political structures. Most of Kokand's troops were tribal irregulars. Even in the 1860s the khan directly controlled no more than 10,000 regular troops. Kokand was weakened by tribal rivalries between the sedentary and largely Iranian populations of Ferghana, and the Uzbek Kipchaks of the north.44 And the dynasty paid a price for its uncertain legitimacy, which encouraged murderous contests for the throne. A series of weak rulers failed to manage the complex alliance systems that had allowed Kokand to expand earlier in the century, and in its final years regional leaders made and unmade khans with a regularity reminiscent of the Golden Horde's “Great Troubles” in the fourteenth century. From the 1840s, Kokand fell increasingly under the control of the powerful and energetic Bukharan Emir Nasrallah.

Though the khanates were still independent in the middle of the nineteenth century, the ominous advance through the Kazakh steppes of Russia's wall of forts made their future look increasingly uncertain. Russian economic influence was also increasing. Since the late eighteenth century, the khanates had provided just enough stability to allow a modest revival of trade, which increased Transoxiana's wealth and attracted Russian commercial interest.45 Bukhara and Kokand concentrated on the China trade, importing silk, tea, and porcelains in return for horses and livestock, as well as opium and Russian furs. The khanates also exported large numbers of horses and livestock to Afghanistan and on to India, trades that explain the size and significance of the Indian commercial diaspora in Bukhara, Kokand, and also in Xinjiang. And the khanates remained at the heart of the flourishing Inner Eurasian slave trade, particularly Khiva, where Turkmen slave raiders sold captives taken mainly from Persian villages or the mountain villages of the Pamirs. In 1873, there were about 100,000 slaves in Khiva, Bukhara, and Turkmenistan.46

Central Asian trade with Russia grew briskly in the early nineteenth century. Arminius Vambery reported in 1863 that “there is no house, and even no tent, in all Central Asia, where there is not some article of Russian manufacture.”47 Central Asian caravans carried raw cotton, cotton cloth, silks, dyes, and fruit to Russia's fortified entrepots in the steppes, and Central Asian cotton became particularly important for Russia's first steam-powered textile factories in the 1830s and 1840s. There was a colony of Bukharan traders in Orenburg in the early nineteenth century, and Bukharans regularly frequented the great Nizhnii Novgorod markets.

THE CONQUEST OF TRANSOXIANA

By the 1860s, Russia was well prepared to conquer Transoxiana. It controlled the Kazakh steppes, its forts reached to the northern edges of Transoxiana, and its armies were being modernized after the disaster of the Crimean War. But in the 1850s and early 1860s, Russia was preoccupied with the Crimean War (1853–1856), and its brutal campaigns of conquest in the Caucasus. These ended with the capture of Shaikh Shamil in 1859, and the conquest of Circassia in 1864. But the Russian government remained unsure of the merits of a military conquest of Transoxiana after the bloody and expensive campaigns in the Caucasus. Though keen to defend the Kazakh steppes, to protect the lucrative trades with Central Asia, India, and China, and to release Russian captives in Transoxiana, Russian officials did not want conflict with Britain in Afghanistan, and were wary of the costs of conquering and administering such a vast and densely populated region.

The government was also ill-informed about Transoxiana. Some of that ignorance was dispelled by the first major diplomatic and trade mission to the emirates of Khiva and Bukhara in 1858. This was led by Colonel N. P. Ignatev, formerly the Russian military agent in London. Ignatev's mission was to increase trade with the emirates, to lower the duties paid by Russian traders, and to ensure that the emirates did not fall under British influence. Though the mission concluded trade agreements, its most important result may have been, in Ignatev's words, to disperse “the fog concealing the khanate from the Russian government.”48 Russian officials became more aware of the region's resources (particularly cotton, which had been an important part of the region's economy since ancient times) and its commercial possibilities. Popular support for advancing into Central Asia was encouraged by journalistic accounts of the presence of Russian slaves, many of them peasant migrants to the Kazakh steppes. Interest in Central Asia was also heightened by a growing sense of Russia's imperial mission.

The government's uncertainty about how to deal with Transoxiana is captured well in an 1864 memorandum by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Prince Gorchakov, written just before Russian troops entered Transoxiana:

The situation of Russia in Middle Asia is that of all civilized states which come into contact with semi-savage and itinerant ethnic groups without a structured social organization. In such a case the interest in the security of one's borders and in trade relations always makes it imperative that the civilized state should have a certain authority over its neighbours, who as a result of their wild and impetuous customs are very disconcerting. Initially it is a matter of containing their attacks and raids. In order to stop them, one is usually compelled to subjugate the adjoining ethnic groups more or less directly. Once this has been achieved, their manners become less unruly, though they in turn are now subjected to attacks by more distant tribes. The state is duty-bound to protect them against such raids, and punish the others for their deeds. From this springs the necessity of further protracted periodic expeditions against an enemy who, on account of his social order, cannot be caught … For this reason the state has to decide between two alternatives. Either it must give up this unceasing work and surrender its borders to continual disorder … or it must penetrate further and further into the wild lands … This has been the fate of all states which have come up against this kind of situation. The United States in America, France in Africa, Holland in its colonies, Britain in eastern India – all were drawn less by ambition and more by necessity along this path forwards on which it is very difficult to stop once one has started.49

Here, expressed in nineteenth-century diplomatic language, were all the familiar dilemmas of empire building in unfamiliar lands. Though dangerous and costly, expansion often seemed necessary to defend earlier conquests. Besides, in an age of imperialism, not to expand when opportunities appeared could be seen as a sign of weakness, particularly if there was a danger of British forces expanding into Central Asia from Afghanistan. Finally, the growing imbalance in the military, economic, and political power of the Russian Empire and Central Asia made conquest seem easier, cheaper, and less risky than ever before. (See Map 11.1)

Russia was drawn into Transoxiana through the lands recently conquered by Kokand. Between 1847 and 1854, Russia built two new lines of forts, one from the Aral Sea along the Syr Darya, the other southward from Semipalatinsk. In 1854, Russia built a fort at Vernoe (modern Almaty). With the formal goal of protecting Kyrgyz tribes on the northern borders of Kokandi territory, Russian forces now entered territory claimed by Kokand. In 1853, General V. A. Perovskii advanced 450 miles up the Syr Darya and captured the fort of Ak-Mechet, giving Russia control of much of the Syr Darya. Soon, Russian ships were sailing the Syr Darya.

The Kokandi-controlled city of Tashkent now offered an extremely tempting target. It was the richest and largest city in the region, with a population of 100,000 and almost 150 separate mahallas. It was also a gateway to trade with China and Transoxiana.50 As a Russian general wrote in 1861, “with Tashkent in our hands we shall not only dominate completely the Kokand khanate but we shall strengthen our influence on Bukhara which will greatly increase our trade with those countries and particularly with the populous Chinese towns of Kashgar and Yarkand.”51

In the middle of 1864, in response to Kokandi attacks, Russian forces advanced from Vernoe in the north-east under Colonel Cherniaev to join up with forces advancing eastwards from the Syr Darya line. The two detachments attacked Tashkent and, though greatly outnumbered, proved superior in discipline, training, and equipment. In June 1865, in disregard of orders, Cherniaev attacked Tashkent for a second time with just under 2,000 men and took the city. Russian casualties were extremely light, and the ancient muskets and cannons of the defenders could do little against the disciplined volleys and modern artillery of Russian units.52 Tsar Alexander II described the conquest of Tashkent as “a glorious affair,” and rewarded Cherniaev's disobedience by granting him a sword set with diamonds, and giving decorations and extra pay to his officers and troops.53

Gorchakov opposed further advances. Cherniaev argued for outright annexation. Others proposed creating protectorates over the khanates. But the next move was decided by events on the ground. In 1866, under pressure from Muslim clergy, Emir Muzaffar of Bukhara (r. 1860–1885) reluctantly declared war on Russia. Within months, his armies had been defeated. In 1868, an imposed treaty, consciously modeled on British treaties with Indian principalities, turned Bukhara into a Russian protectorate. In an 1873 revision of the treaty, the emir lost control over Bukhara's foreign policy and had to acknowledge himself “the obedient servant of the Emperor of All the Russias.”54

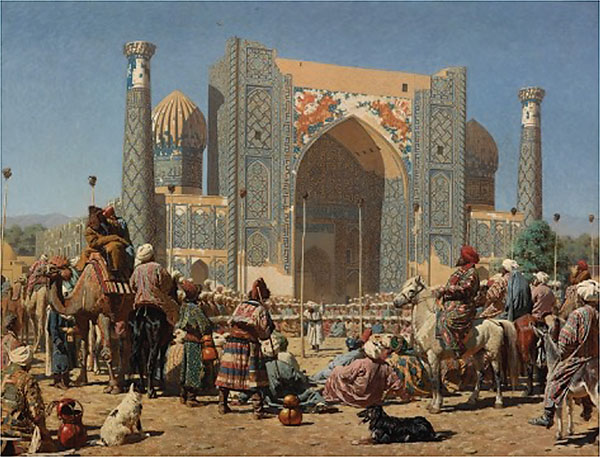

In 1867, the Russian government created a Turkestan Governor-Generalship under the command of K. P. von Kaufman (1818–1882). It included the Samarkand region, which was severed from the Bukharan emirate under the 1868 treaty. (See Figure 11.1.) Kaufman reported directly to the emperor, and governed the region until 1881. In the areas under his control, Kaufman began creating a governmental system which, like British rule in India and Chinese rule in Xinjiang, left most local authority to local Central Asian officials.

Figure 11.1 Vasilii Vasilievich Vereshchagin, They Triumph, 1872, shows Samarkand's central square, the Registan, after a battle during the Russian conquest of Central Asia. Vereshchagin traveled in Central Asia during the years of Russia's conquest of the region. This depicts the impaled heads of Russian troops in what was still part of the Bukharan emirate. It is an imperialist and orientalist vision, but was painted by an artist who did know the region. Courtesy of Tretyakov Gallery.

Conflicts with Khiva provoked Russian attacks from both Tashkent and the Caspian region. In 1873 Khiva, too, became a Russian protectorate, and some of its territory was hived off to the Turkestan Governor-Generalship. After trying to flee, the emir of Khiva was forcibly restored to power, and required to sign a treaty with Russia and abolish slavery. Kokand was conquered outright in 1875, after its forces attacked Russian troops. The following year, Kaufman stormed Andijan and abolished the Kokand khanate.

Wary of the financial and administrative costs of direct rule, and of its implications for relations with China and Britain, the government left the cut-down Bukharan and Khivan emirates as formally independent polities. They would retain formal independence until the collapse of Russia itself in 1917, but both lost territory, and their rulers were supervised by resident Russian “political agents.”

In practice, Russian conquest allowed the emirs of Bukhara to consolidate their power, as the presence of Russian troops enhanced their power in relation to regional tribal chiefs and to the Muslim clergy. Emir Abd al-Ahad (r. 1885–1910) presented himself to his subjects as the last defender of traditional Islam against the Russian invader. To the Russians he presented himself as a bastion of stability in a dangerous and hostile environment. Under Russian protection, Bukhara's last emirs accumulated great wealth. When the last emir, Alim Khan (r. 1910–1920), sought British help to flee abroad, he promised to bring assets worth £35 million.55

The conquest of Turkmenistan proved more difficult because here, as in parts of the northern Caucasus, there was no single polity to conquer or control.56 In 1869 and 1873, Russian forces established bases on Turkmen territory on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea, at Krasnovodsk and Mangashlyk. In 1879, Turkmen fighters, mostly of the Tekke tribe, defeated Russian troops at the desert fortress of Geok-Tepe, near modern Ashkhabad. They killed some 200 Russian troops in Russia's most serious military defeat in Central Asia. Two years later, troops from Russia's Caucasus command conquered most of modern Turkmenistan. General Skobelev conquered Geok-Tepe in January 1881, and massacred most of the Turkmen forces, insisting that “the duration of peace is in direct proportion to the slaughter you inflict upon the enemy. The harder you hit them, the longer they remain quiet.”57 The capture of Merv, in 1884, completed the conquest of Turkmenistan. After negotiating a border between Russian Central Asia and British-controlled Afghanistan in 1887, Russia would advance no further south until the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

At relatively little cost, the Russian Empire had conquered an area the size of western Europe, with a population of 9 million people, rich agricultural and commercial resources, and historical and religious traditions older than its own. Russian patriots celebrated. After Skobelev's conquest of Geok-Tepe in 1881, Dostoyevsky wrote: “In the whole of Asia, Skobelev's victory will resound, to its farthest borders … [demonstrating] the invincibility of the white tsar.”58

RUSSIAN RULE IN TRANSOXIANA

In Transoxiana, Russia established a system of imperial rule similar to that of British India, with strong central control but limited political or cultural influence at the local level. The military dominated the administrative and judicial structures of colonial rule. The Governor-Generals and most of their subordinates were military officers so that, until 1917, Russian administration retained the quality of an occupying army. In 1912, the future minister, A. V. Krivoshein, wrote:

When one has seen the universal predominance of the natives in Turkestan, one cannot but feel that this is still a Russian military camp, a temporary halting place during the victorious march of Russia into Central Asia.59

Few Russians could be found in the villages or in the mahallas of the towns and cities, and Muslim judges, village elders or aksakals, and fiscal officials continued to be elected in traditional ways.60 In the khanates, legal and governmental traditions survived as well. In Khiva, judicial torture was not officially abolished until 1888. Even modernizing reforms such as the abolition of slavery could have unexpected results. In Turkmenistan, it removed an important source of income and the labor of Turkmen women often replaced that of agricultural slaves. The end of slave raiding left many males without a traditional career, and in 1881, soon after the battle of Geok-Tepe, a foreign traveler noted that many men had turned in despair to alcohol and opium.61

With its large populations and ancient cultural traditions, Central Asia would never become as Russified as other conquered regions, even Muslim regions such as Kazan’ or Crimea. It is symptomatic that, while legally Central Asians were classified as inorodtsy, like other indigenous populations of the empire, Russian officials in the region described them as tuzemtsy, or “locals.”62 Cultural differences between colonizers and colonized remained stark, as in much of the Caucasus. While some Central Asian leaders and merchants moved between both worlds, educating their children in both Russian and Muslim schools, most Central Asians, or “Sarts” as the Russians called them, were barely touched by Russian culture, and continued to seek education within the traditional maktabs and madrasas. In Transoxiana, as in much of the Caucasus, Islam provided a sense of cultural cohesion, and of difference from the imperial heartland and its culture. Ferghana, which would become the center of the Basmachi resistance movement in the 1920s, was particularly important in this regard. Here, anti-Russian sentiment, often supported by local mullahs or Sufis, would provoke many small uprisings in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.63

Russia's administrative system preserved regional traditions by ignoring them. This allowed the survival of the traditional ulama, of many madrasas, and of the traditional Muslim courts overseen by elected qazis. Indeed, Central Asia's religious elites survived the conquest better than its political or tribal elites. In any case, Russia's colonial administration was chronically short of cash, so Russian Turkestan was seriously under-governed. Syr Darya province, with a population of almost 1.5 million in 1897, was managed by just 19 officials when first created in 1867. Forty years later, in 1908, Ferghana province's population of 2 million was managed by 43 officials, of which only two were translators.64

Russia's impact was greater in the towns. Russian towns grew up around army garrisons, often alongside ancient Central Asian towns. They attracted Russian traders, railway workers, and officials, and also a considerable number of illegal Russian migrants. The contrast between the traditional city, with its warren of streets and houses built around courtyards with no exterior windows, and Russian quarters built according to geometric plans along wide avenues, is still apparent today in cities such as Samarkand, Tashkent, or Bukhara. In this as in other things, Kaufman set a precedent with his plans for building a European city at Tashkent. Lord Curzon, who visited the city in 1889, found that the worlds of Russians and natives were even more distinct than in British Indian towns. By 1910, the Russian city of Tashkent occupied as large an area as the native city, though it had just a quarter of the population. Stephen Graham, who visited in 1914, found that the military still set the tone of the Russian city. But he also noticed a superficial Europeanization of some of the city's local population.

There are six cinema shows at Tashkent, two theatres, an open-air theatre, a skating rink, and many small diversions. The native turns up in the cinema, and there are generally long lines of turbaned figures in the front of the theatre. At the real theatres it is necessarily those who know Russian who take the seats. At the open-air theatre they play The Taming of the Shrew, at the Coliseum the Doll's House and Artsibasheff's Jealousy.65

Eventually, there emerged a small, Russified, Central Asian intelligentsia, whose members were interested in modernization, in modern education, and in modern forms of nationalism. Tatar intellectuals from the Volga and Crimean regions took the lead in attempts to forge new Turkic and Islamic national or cultural identities.66 Kazan’ had long been a commercial and intellectual intermediary between Russia and Central Asia, but its Muslim intellectuals also felt strong links to Bukhara, as an ancient center of Islamic learning. Many Turkic intellectuals were inspired by the writings of a Crimean Tatar, Ismail Bey Gasprinskii (1851–1914). In his newspaper, Terjiman (“The Translator,” first published in 1883), Gasprinskii argued for modern forms of education, including science and history as well as modern languages. He also argued for a common Turkic language, and the emancipation of women. Gasprinskii himself had traveled widely, living for a time in Moscow, where he was a student in a military academy, and in Paris, where he worked for a time as Turgenev's secretary. He introduced the first “new method” school in Crimea in 1884, and by 1900 such schools were common in Crimea and among Russia's Tatar population.67 The idea of a new form of education that would teach literacy and combine religious and secular education so as to prepare young Muslim students for the modern world came to be known as the “new method” education (usul-i jadid), or “Jadidism.” Jadidism would put educational reform at the heart of discussions about reform in the Muslim societies of Inner Eurasia. Gasprinskii himself saw the maktabs and madrasas of Bukhara as a symbol of all that was worst about Islamic conservatism.68

Attempts to forge a new pan-Turkic national identity within the Russian Empire would not succeed, partly because of splits between secular nationalists and those committed to traditional Islam, and partly because the Turkic languages of the empire had moved too far apart. In Tashkent, most Tatars (often described as “Nogais” by Russian officials) were so Russianized that they lived separately from other Central Asians, sent their children to Russian schools, and even dressed differently. Mehmed Zahir Bigiev, a Tatar who traveled in Central Asia in 1893, was shocked by the “complete ignorance of the world” of the famous madrasas he visited in Bukhara and Samarkand.69 But whether Tatar or Central Asian, the emerging intelligentsia was too small to have much impact on the 95 percent of the population who remained illiterate. As a result, Central Asia's first modern revolutionary movements would be dominated by Russian immigrants.70

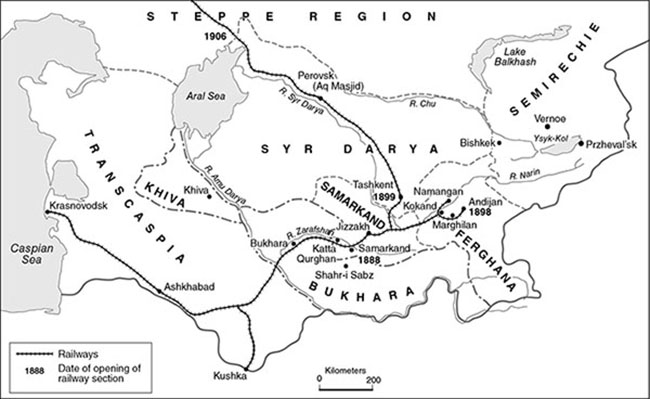

Russia ruled Central Asia not just through its armies, but also with modern technologies, of which the railway and telegraph were the most important. Here, as elsewhere in Inner Eurasia, vast distances meant that cheap and efficient ways of moving people, troops, goods, and ideas could prove transformative. (See Map 11.2.)

Map 11.2 Central Asia after Russian conquest. Khalid, Politics of Muslim Cultural Reform, xxiii, showing railways. Reproduced with permission of University of California Press.

By 1869, there was already a telegraph line between Russia and Central Asia. Printing arrived with the Russians but took off after the introduction of lithographic printing in 1883.71 Print was transformative in a society in which important knowledge had been disseminated primarily by word of mouth, from teacher to student. Traditional sharia law depended on the interpretation of printed texts by jurists so, in contrast to western legal traditions, no one expected printed laws to be self-explanatory. That is why increased reliance on printed texts was such a profound threat to older ways of thinking and older forms of knowledge. As Adeeb Khalid puts it, “Unlike the decades’ worth of learning in the madrasa that provided entrée to the cultural elite, access to the new public space required only basic literacy. … In the new public [space], the older cultural elite was increasingly marginalized.”72

Railway building transformed military and economic relations. In 1880, a military railway line was built from the Caspian Sea to Ashkhabad. By 1888 it reached Samarkand, and by 1900 it had reached Tashkent. The railway replaced older routes to Russia that used desert caravans to Krasnovodsk on the Caspian Sea, steamers to Baku or Astrakhan and train or river steamers to Moscow. Railways (and protective tariffs) killed off the traditional caravan trade to Russia and India. Soon it was cheaper and quicker to send goods by rail to Odessa and then by sea to Bombay than by caravan through Afghanistan.73 Railways also killed off many traditional urban crafts by bringing industrially produced Russian goods. The opening of the Orenburg–Tashkent Railroad in 1906 accelerated Transoxiana's economic incorporation within the empire. The Turksib railway, which would not be completed until 1930, was begun just before 1914, to ease the transport of cheap grain from Semirechie and western Siberia.

Cotton proved the most profitable of local crops, because it provided cheap raw materials for the empire's multiplying textile factories in Russia and Poland. Cotton was still produced by numerous small farmers, so it helped create a large and prosperous new class of Central Asian middlemen and merchants.74 Cotton production grew rapidly after the introduction of American varieties of cotton, because traditional Central Asian cottons were difficult to work and could be used only for inferior textiles. In 1884, Kaufman encouraged plantings of American varieties of long-fiber cotton; by 1888, large areas were devoted to American varieties, mainly in the Tashkent and Ferghana regions; and by the early twentieth century, American cotton had displaced local varieties in much of Central Asia. Cotton exports were carried at first on large camel caravans, but eventually by rail. They soon began to attract Russian commercial investment.75 Railways cheapened the export of cotton and fruit to Russia, and allowed the import of Russian grains to replace subsistence crops such as wheat, rice, alfalfa, and sorghum that had been displaced by cotton. Central Asia also offered a useful protected market for Russian manufactured goods, including iron and steel, which struggled to compete on international markets.76

However, cotton is a thirsty and demanding crop, and as its commercial importance grew, particularly for Russia, it began to take up more and more land and use more and more water, until it began to displace subsistence crops, warping the entire Central Asian economy in the interests of the empire. As Russia's Minister of Agriculture put it in 1912:

Every extra pud of Turkestani wheat [provides] competition for Russian and Siberian wheat; every extra pud of Turkestani cotton [presents] competition to American cotton. Therefore, it is better to give the region imported, even though expensive, bread, [and thus] to free irrigated land in the region for cotton.77

In 1885 about 14 percent of cultivated land in Ferghana was devoted to cotton. By 1915, cotton accounted for 40 percent of cultivated land in Ferghana, and perhaps half of all agricultural production in Russian Central Asia.78 Transoxiana, which had long been self-sufficient in grain and rice, now had to import both crops.

Cotton production supported a growing merchant class, and the associated economic boom drove urbanization. Tashkent's population grew from c.75,000 in 1870 to almost 250,000 in 1911. By 1911, the population of Samarkand was almost 90,000, while Kokand, in the heart of the cotton-growing region, had grown to over 110,000.79 Cotton drove many rural producers into debt. In spring, when most peasants were short of cash, cotton traders or tarazudars offered loans in cash and kind (including manufactured goods or tea, soap, and paraffin) in return for a commitment to produce a fixed amount of cotton at prices determined in advance by the traders.80 Like Chinese moneylenders in Mongolia, the cotton traders were in a strong position because of their links to the imperial power, though Russian officials in the region tried hard to limit indebtedness, rightly fearing it would encourage anti-Russian feeling.

The incorporation of Central Asia's economy into the Russian mobilizational system could not have taken place without a transformation in landownership as profound as the one that Russia had undergone in 1861. In 1886, tenants of waqf lands were declared hereditary owners of the land they used, and in 1913 all tenants were given ownership of their lands.81 Combined with the introduction of local elections, these changes destroyed the authority of traditional tribal elites, and may have helped reconcile much of the local population to the new Russian authorities. But, like cotton production, they also forced traditional farmers into market relations, exposed them to debt and bankruptcy, and allowed a new concentration of landholding in the hands of new commercial elites. Cotton growing forced more and more peasants to buy their food, often at inflated prices. Increasing numbers of peasants were transformed into day-laborers, or sharecroppers, many of whom had to surrender up to 80 percent of their harvest.82

By 1900, though culturally very different from the rest of Russia, Transoxiana had been successfully incorporated into the Russian imperial mobilizational machine. The region's economic and political fate was determined increasingly by decisions taken in the Russian heartland. Yet many aspects of its traditional culture would be protected, unwittingly, by a colonial regime that was underfunded, and more interested in cotton than in cultural change.

RUSSIA IN SIBERIA AND THE FAR EAST

By 1700, there were probably 300,000 Russians in Siberia; by 1800 there were 900,000. That was probably three or four times the number of indigenous Siberians. By 1850 there were 2.7 million Russians and by 1911 almost 8 million. By 1914 the population of Siberia had reached 10 million, as a result of a mass migration as significant in its scale and impact as that of European migrations to the USA in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.83 By the middle of the nineteenth century indigenous Siberians accounted for less than 20 percent of Siberia's population and by 1911 for less than 10 percent. Most Russian settlers lived in western Siberia. In the 1760s, a quarter of all Russians lived east of the Yenisei; in 1900, only about one fifth lived in eastern Siberia.84

SIBERIA AND THE FAR EAST BEFORE 1850

In the mid-eighteenth century, Siberia, like the neo-Europes of North and South America, consisted of expanding regions of European settlement and outlying regions in which indigenous populations came under increasing demographic, fiscal, military, and even epidemiological pressures that undermined traditional lifeways.

The Russian government mobilized resources, above all furs, through a network of forts established at strategic points along Siberia's major rivers, mostly in the forested southern half of Siberia. Settled by Cossacks, government officials, merchants, exiles, and increasing numbers of peasant immigrants from Russia, the forts turned into small towns and even cities, from which officials, soldiers, and merchants set off to control the more remote regions of the north and far east. Indigenous communities felt increasing pressure through demands for tributes (iasak), the taking of hostages, the occupation of traditional hunting grounds, new diseases, attempts at religious conversion, and occasionally military attacks.

Given Siberia's vast size, efficient communications between forts and towns were the key to mobilizing its resources. Rivers were Siberia's first roads. But from the 1740s, a post-horse system linked forts and towns along the northern edge of the Kazakh steppes. But it was slow. In 1787, a British traveler took two and a half months to travel from St. Petersburg to Irkutsk. Beginning in 1763, Russia built a road from Tiumen’ to Krasnoyarsk, known as the Siberian “trakt.” Though best known as the route by which convicts traveled to Siberia, the trakt also encouraged immigration and trade. Caravans and sledges began to carry goods and people along the new road.85 The trakt altered Siberia's urban geography, favoring towns through which it passed, such as Tiumen’, Tomsk, and Irkutsk, and marginalizing the towns it bypassed. The trakt explains why Tobolsk was displaced by Omsk as the capital of Siberia in 1824. New settlements multiplied along the trakt, even in remote regions such as the Baraba steppes, many of them settled by exiles.86

Farming and the discovery of metals turned Siberia into more than a fur quarry. The iron and copper of the Urals was exploited systematically from the time of Peter the Great, under the direction of a Tula gunsmith, N. Demidov. By the end of Peter's reign, the Urals had become one of Europe's major producers of iron, and Yekaterinburg was the region's industrial center. Further east, also in Peter's reign, silver and lead were discovered near Nerchinsk.87 In the 1830s, gold would be discovered in Buriatia, on the Mongolian border, and metals began to rival furs as the main driver of Siberian trade.88

However, furs remained important, particularly in eastern Siberia. The fur trade had a huge impact on indigenous lives because it reached into every corner of Siberia. Peter I had established a government monopoly on the sale of sables as early as 1697, and officials in eastern Siberia were ruthless in their demands. In 1697, a Russian expedition from Anadyr led by a Cossack, V. Atlasov, entered the Kamchatka peninsula. The local Itelmen population lived in independent forest villages, from hunting and fishing. In summer, like many communities in northwestern North America, they took large quantities of salmon. Because there was no political organization above the village level, and villages often fought each other and took captives as slaves, imposing the government's will meant conquering the region, village by village.89 The conquest took 50 years of savage fighting, during which 24,000 sables were taken, as well as many other furs. By 1738, the Itelmen population had fallen by almost half to about 7,000 and, though they now had firearms, they could no longer put up active resistance.90 By 1820 there were fewer than 2,000 Itelmen, most of whom were fully Russianized and lived like Russian settlers.91

To the north of Kamchatka, Russian forces encountered the Korak peoples, and, in the far north-east of Siberia, the Chukchi. The Korak and Chukchi had long traditions of inter-tribal warfare, and put up skillful and determined resistance, so the conquest of these regions also took the form of many small, but barbaric conflicts. In 1742, the Russian Senate issued an order demanding the extermination of Chukchi and Korak, or their settlement as farmers. In 1744–1747 a Cossack major, Pavlutskii, led an army of Cossack, Korak, and Yukagir to fulfill this order, until he was killed himself, leaving his head among the Chukchi who kept it as a trophy for many years.92

Korak numbers declined from about 13,000 in 1700 to fewer than 5,000 by the 1760s. They submitted formally in 1757–1758. But these wars were also costly for Russia. In 1764 the government abandoned Anadyr fort, the center of its operations in the far north-east, and the Chukchi, further north, mostly survived. Indeed, their numbers eventually increased as Russian governments adopted more peaceful methods of control, including trade and treaties, some of which recognized Chukchi rights over their lands. The extreme cold of the Chukchi homelands may have spared them from diseases such as typhus, which had decimated the Itelmen and Korak in Kamchatka.93

The momentum of the fur trade eventually carried Russian soldiers and colonizers into the Americas, where they encountered Europeans who had followed furs in the opposite direction, westwards, through North America.

Russian interest in North America began with an official expedition of exploration, under the Dane Vitus Bering, that left St. Petersburg in 1725, arrived at Okhotsk in 1727, and then entered the straits that now carry Bering's name. A second expedition under Bering left the new Kamchatkan port of Petropavlovsk in 1741 and discovered the Aleutian Islands. After learning that Captain Cook had sold sea otter pelts in China at a significant profit (they were highly valued at the Qing court), Bering began seeking sea otters in North America.94 In 1799 a Russian American Company was founded, modeled on the British Hudson's Bay Company and the East India Company, but designed primarily for the trade in sea otter furs.

Russians demanded sea otter and fox furs from the Aleutian (Unangan) islanders using traditional coercive methods. They settled on the island of Kodiak in 1784, using Aleuts as fighters in wars with mainland tribes, and began building forts along the Alaskan coast. Eventually, they built forts further south to supply grain for their Alaskan settlements. The furthest south was Fort Ross (“Rossiia”), just north of modern San Francisco, which was built in 1811. By the 1830s, 800 Russians lived in Alaska and the nearby islands, but this was too small a community to prevent British and American encroachment. Eventually, overhunting of sea otters, and the high cost of maintaining settlements so far away, persuaded the government to sell Fort Ross in 1841. In 1867 Russia sold Alaska to the US government for $7.2 million, ending its brief foray into the Americas.95

By the middle of the nineteenth century, most Siberian natives had lost their independence, and many elements of their traditional lifeways. Tribute and warfare exacted a huge toll, but so did smallpox, influenza, typhus, and syphilis. Commerce and cash undermined traditional lifeways because, as traditional subsistence activities lost their viability, local populations had to buy goods they had not needed before, including firearms, knives and gunpowder, vodka, tobacco, and many other goods supplied by Russian merchants. Sometimes they even had to buy furs to meet their iasak obligations. Bought on credit, such purchases left many in debt, and defaulters could be sold as slaves or forced to surrender traditional lands. Interest payments could accumulate fast. Within a few years, the debt on a small purchase such as an ax or a pair of boots could equal the value of an entire herd of horses.96 Until its abolition in 1825, the slave trade flourished in cities such as Tomsk, Tobolsk, and Yakutsk, which sold captives taken by the Kazakh or Kyrgyz, or enslaved in local wars or forced into debt slavery.97

In the eighteenth century, Russian governments also began to put religious pressure on the populations of Siberia. Peter the Great required all natives to convert to Christianity and demanded oaths of loyalty to the Russian Tsar. This last decree provoked a rebellion amongst the growing Muslim population of Tara, on the Irtysh, south of Tobolsk, which had become the main center for trade with Central Asia and the home of many of the Central Asian “Bukharans” who managed Russian trade in Siberia and the Kazakh steppe.98 Under Catherine the Great, policy towards non-Orthodox religions softened. West Siberian Tatars or “Bukharans” were allowed to build mosques, and by 1851 there were 188 mosques in western Siberia, mostly in Tobolsk province. In any case, most conversions to Christianity were superficial. Shamanistic beliefs and practices survived among the native population, and Christian saints such as St. Nicholas were adopted by local tribes such as the Khanti and the Yakut. The once shamanistic Buriat Mongols became Lamaist Buddhists in the eighteenth century. In the 1740s, the Russian government permitted the founding of lamaseries, and in 1764 it allowed the appointment of a Buriat chief lama. Mongol influences and Lamaist traditions of literacy explain why the Buriats were the only Siberian native peoples to have their own written language before 1917.99

Far from St. Petersburg, corruption was widespread and spectacular in Siberia. The first governor of the new province of eastern Siberia, created in 1756 with its capital at Irkutsk, was executed for corruption and extortion. Corruption reduced government revenues, so the central government worked hard to create a more law-abiding administrative system, but its efforts often had damaging side effects. The reforms introduced in 1822 by M. M. Speranskii were prompted by the corruption of his predecessor, Pestel. Though enlightened in their goals, Speranskii's reforms imposed laws and structures incompatible with traditional lifeways, beginning with the claim that the Russian state, not the local peoples, owned the lands of Siberia. Speranskii's reforms created three distinct categories of peoples: the settled, the nomadic (who pursued regular, predictable annual migrations), and the “wandering” (whose migrations were less regular). However, most Siberian peoples crossed all these categories, and the real effect of the reforms was to force many to become sedentary. As those in the “settled” category were subjected to the same laws and taxes as Russian state peasants, this meant paying new taxes, sometimes in addition to the traditional iasak.100

The Russian government used Siberia not just to extract resources and revenues, but also as a dumping ground for criminals and dissidents. By 1900 there may have been 300,000 exiles in Siberia, about 5 percent of its total population.101 Criminals, religious dissidents, beggars and prostitutes, prisoners of war, and political exiles all ended up in Siberia. Prisoners of war and political dissidents in particular created an intelligentsia amongst the Russian settlers, and laid the foundations for modern scholarship on Siberia's history, ethnography, and geography. Such educated dissidents included 90 of the Decembrists who had rebelled in 1825, writers from Radishchev to Dostoyevsky, Polish nationalists (a group that multiplied after the first partition of Poland in 1772, but was topped up after the Napoleonic Wars and the risings of 1830 and 1863), and later, socialists and populists including both Lenin and Stalin.

AFTER 1850: EASTERN SIBERIA, THE TRANS-SIBERIAN RAILROAD, AND MANCHURIA

In the late nineteenth century, the sale of Alaska and diminishing returns from furs reduced government interest in the Arctic regions of Siberia. The few Russians who settled in the Far North began to live like the local peoples; some adopted local languages and ceased to speak Russian. In the Far North, contacts with the empire were mediated by traders who visited native villages, where they bought furs, mammoth tusks, reindeer skins, and other local products in return for tobacco, tea, furs, guns and ammunition, knives, and other domestic metal goods. All trading involved vodka and it usually left natives deep in debt. But natives also adapted by altering their migration patterns to avoid new settlements or mines, whose inhabitants often seized their reindeer. Some leased their lands to commercial fishermen.102 The Chukchi began to trade with American Alaska, exchanging whalebone, walrus tusks, and reindeer hides for rum, molasses, knives, and Winchester rifles, which were cheaper and of higher quality than Russian trade goods. Many learnt American English rather than Russian.103

In the Far East, Russian Siberia began once again to encroach on China's sphere of influence in the Amur region and Manchuria. As in Central Asia, most advances were initiated by local commanders. In 1849, aware of increasing Chinese military weakness after the Taiping rebellion (1850–1864), a Russian naval commander, Gennadii Nevelskoi, hoisted the Russian flag at the mouth of the Amur. He wisely named the settlement Nikolaevsk in honor of Nicholas I (r. 1825–1855), and soon received Nicholas's retrospective backing for this bravura display. In 1854, Nikolai Muravev, who had been appointed governor of eastern Siberia in 1847, conquered the Amur region, which Muscovy and the Qing had contested in the late seventeenth century. Muravev built a fort at what is now Khabarovsk and once more St. Petersburg gave its blessing. Russia occupied the Island of Sakhalin, previously claimed by Japan, in 1853, and acquired it formally by treaty in 1875. In 1860, Vladivostok was founded just north of the Korean border, giving Russia a window on the East to match St. Petersburg's window on the West. The Chinese government had to accept what it could not prevent.

Once conquered, these distant acquisitions had to be defended, and that provided one of the justifications for building the Trans-Siberian railroad. Construction began in 1891, and by 1903 a single track ran the entire route. Like the Siberian trakt, the Trans-Siberian railroad had a profound effect on the towns and villages along its route. It accelerated migration, increased commercial exchanges, and allowed the rapid deployment of troops across the entire continent. It also encouraged imperial ambitions in the Far East. In 1893, Sergei Witte wrote to the Tsar:

On the Mongol–Tibetan–Chinese border major changes are imminent, which may harm Russia if European politics prevail there, but which could bring Russia countless blessings if we forestall western Europe in East Asian affairs. … From the shore of the Pacific and from the heights of the Himalayas Russia will dominate not only the affairs of Asia, but those of Europe as well.104

Many shared Witte's visions of Russia's future in the Far East, including the English geographer Harold Mackinder, who wrote in 1904, just before the Russo-Japanese War:

The Russian army in Manchuria is as significant evidence of mobile land-power as the British army in South Africa was of sea-power. True, that the Trans-Siberian railway is still a single and precarious line of communication, but the century will not be old before all Asia is covered with railways. The spaces within the Russian Empire and Mongolia are so vast, and their potentialities in population, wheat, cotton, fuel and metals so incalculably great, that it is inevitable that a vast economic world, more or less apart, will there develop inaccessible to oceanic commerce.105

Such ideas encouraged Russian imperial ambitions. Between 1896 and 1903, China allowed Russia to build a “Chinese–Eastern Railway” through Manchuria to Vladivostok and south to Port Arthur. In 1900, in the wake of the Boxer uprising, Russian forces occupied much of northern Manchuria to protect the railway.106 When the Russian government delayed on its promise to return Manchuria to China, Japan, which had industrialized rapidly in the decades since the Meiji restoration in 1868, and had its own ambitions in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia, launched a surprise attack on Port Arthur in January 1904. Japanese commanders understood how vulnerable Russian forces were at the end of very long supply lines, but they also understood that Russian power would steadily increase as the railway improved. In May 1905, in the straits of Tsushima, the Japanese sunk a Russian fleet sent around the world from the Baltic. A bloody stalemate in the fighting on land was resolved when revolution at home forced the Russian government to accept American offers of mediation and conclude the treaty of Portsmouth in August 1905.

Russian armies might well have won the Russo-Japanese War with better military decisions on land, more effective use of its navy, and greater political stability. Indeed, at the end of the war, Russia had more troops in Manchuria than Japan, whose armies were near to collapse.107 The Russian mobilizational machine nearly did what it had done so many times before. But with Russian forces at the end of thinly stretched lines of communication, and revolution in the heartland, a weakened and indecisive Russian government lost its nerve.

CHINA'S INNER EURASIAN EMPIRE

While Russia's empire expanded in Central Asia and the Far East, China's empire in Manchuria, Mongolia, and Xinjiang crumbled.

MONGOLIA BEFORE THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

Since the treaty of Dolonnor in 1691, and the defeat of the Zunghar Empire half a century later, Mongolia had become once more a colonial dependent of a Chinese Empire. In Qing thinking, the emperor was the direct ruler of Mongolia, as of Tibet, in his role as an incarnation of the Bodhisattva Manjushri.108

While the Oirat heartlands of the Zunghar Empire had been devastated, the Khalkha Mongol lands also suffered during the Zunghar wars, because of the military and tax burdens imposed to pay for them. But unlike Inner Mongolia, and much of Zungharia, Khalka Mongolia was not opened to Chinese migration, though it was opened to Chinese merchants, who soon dominated Mongolian commercial networks.

Mongolia had few towns. Most important by the late eighteenth century was Khuriye, the once nomadic tent city or ordo of the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu. Towns and lamaseries offered opportunities for employment or protection that could not be found in the steppes. As the headquarters of the Jebtsundamba Khutugtus, Khuriye attracted many lamas. They, in turn, drew in merchants and tradespeople. After the treaties of Nerchinsk (1689) and Kiakhta (1728), Khuriye had become an important stopping point for Russian and Chinese caravans traveling from Kiakhta to China. Here, they catered to the needs of the lamas and officials that gathered around the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu, and changed their horses and oxen for camels before heading south into the Gobi desert.109

Khuriye became a permanent town after 1778, when it settled where the Selbe river joins the Tuul river, at the site of modern Ulaanbaatar. The Tuul river supplied it with water, and BogdKhan mountain to the south shielded it from cold winter winds. Foreigners called the town Urga, after the Mongol word “örgö,” or “royal yurt.” Mongols referred to it as “Da Khuriye,” or “Great Lamasery.” Elsewhere, military camps such as Khobdo and Uliasutai also turned into permanent towns, but none were as large as Khuriye, though even Khuriye had no more than 7,000 people in 1820, a thousand of whom were lamas. The building of Gandan monastery in 1809 enhanced Khuriye's importance by providing a symbolic balance to the monastery of Erdeni Zuu in the former capital of Karakorum.110 The evolution of steppe towns such as Khuriye was a story that travelers through Khan Mongke's empire would have found familiar.

The larger lamaseries encouraged a low-grade urbanization, as sedentary populations of monks, clerks, artisans, and officials clustered around them. By the nineteenth century, there were 1,900 lamaseries in Inner and Outer Mongolia, and 243 living Buddhas. Most families had at least one son in a lamasery, so that monks may have accounted for one third of the male population in what amounted, in practice, to a form of welfare for poor nomadic households.111 The increasing number of formally celibate men who ended up in lamaseries may help explain Mongolia's demographic stagnation before the twentieth century.112 In 1800, Mongolia's population was probably smaller than in the time of Khan Mongke.

Chinese taxation was burdensome. Worst was the requirement to maintain the post-horse system and supply military garrisons, particularly along the border with Russia. Local communities had to support watch posts, each with 30 or 40 soldiers. That meant providing food, well-fed horses, clothing, and arms. In a largely non-monetary economy, the requisitioning of horses was particularly burdensome because, even if horses were paid for at their full value, herders lost their breeding potential, the main source of income for nomadic households and for the Mongolian economy as a whole.113 Mongolian nobles paid a heavy price in the ceremonial expenses associated with compulsory attendance at court functions in Beijing. In 1832 the zasag (or prince of a local “banner”) of Setsen aimag (or province) had to go to Beijing for New Year ceremonies. His costs, amounting to 5,000 taels (at a time when a soldier's pay was 18 taels a year), included payment for five camels used to transport ice from the Kerulen river, for the prince's personal use.114

New commercial networks were created in what had been a world without cash, mostly by the activities of Chinese merchants, who set up shops in the towns, or visited local settlements and lamaseries with their goods. Such networks gave Chinese merchants commercial power over all classes, particularly through the sale of goods on credit, which could create long-term indebtedness. By the later nineteenth century, Chinese merchants faced competition from Russian and Siberian traders.115

Qing administrative structures had weakened traditional political ties and created new local loyalties. The Qing had divided Mongolia into almost 50 banners (khoshuu). Officials used maps to fix the borders of each banner. Each was ruled by a governor or zasag, usually a local prince, from a banner center that was often just a collection of tents.116 The population of each banner was divided into sums, or “arrows,” each of which had to supply 50 troops. The Qing restricted movement between banners to make tax collection easier, but this cut traditional migration routes and undermined the authority of the clan leaders who had traditionally allocated migration routes. The erosion of traditional clan structures explains why rebellions were rare. When it occurred, protest took isolated, elemental, and spontaneous forms, and there would be no large rebellions until Qing power collapsed in 1911. Anti-Chinese riots were usually little more than drunken attacks on Chinese shops or traders.117

Like the Russian Empire, Qing Mongolia consisted of two broad groups, representatives, respectively, of the mobilizers and the mobilizees. The taiji or hereditary nobles and princes (technically descendants of Chinggis Khan) were free from taxation and symbolized by the color white.118 In the early nineteenth century, taijis could account for 10 percent of non-monastic lay males. Commoners, symbolized by the color black, were classified as the albatu (who served the state administration in the banners), the khamjilga, or serfs of the taiji (a status not abolished until 1923), and a smaller group of shabi, or lamasery serfs. There was a small class of slaves, many of them bankrupt debtors, or children sold by impoverished parents.119 Lamas made up a distinct class, symbolized by the color yellow. High lamas had similar privileges and rights to taijis. By the mid-nineteenth century, there were as many as 120 khutughtus in the Khalkha lands and Inner Mongolia, and their leader, the Jebtsundamba Khutugtu, owned tens of thousands of shabi.120