[14]

1930–1950: THE STALINIST INDUSTRIALIZATION DRIVE AND THE TEST OF WAR

INTRODUCTION

After 1929, the Stalinist mobilizational drive swept like a hurricane through Inner Eurasia, transforming institutions, people, ideas, lifeways, and landscapes. After 1941, the Stalinist hurricane merged with the even larger storm of World War II. The twin storms of industrialization and war left behind vast amounts of human and material debris, but they also dragged the Soviet Union into the era of fossil fuels. In its dependence on mobilizational pressure and on foreign technologies, the Stalinist industrialization drive was similar to the mobilizational drives of seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Muscovy. But the impact of Stalinist industrialization was magnified many times over by the power of industrial technologies, by the vast energies released by fossil fuels, and by the compression of colossal changes into just two decades.

This chapter continues the story of the previous two chapters, and maintains the focus on the heartlands of Inner Eurasia, which drove most major changes in most of Inner Eurasia for most of the twentieth century.

THE LEFT TURN AND COLLECTIVIZATION: 1929–

Despite simmering internal conflicts, by 1929 the Communist Party was united behind a strong new leader, Stalin, who would show himself to be as able, decisive, and brutal as Peter the Great. Ruling-class unity rested not just on shared goals, but also on political networks held together by ties of patronage, Party discipline, and hopes for a better future, managed by the Secretariat, and institutionalized within a nomenklatura structure similar to Peter's Table of Ranks. The unity and discipline of this elite allowed the government to build the world's first modern “command economy,” that is to say, a modern industrial economy,

in which the coordination of economic activity, essential to the viability and functioning of a complex social economy, is undertaken through administrative means – commands, directives, targets and regulations – rather than by a market mechanism.1

This was never really a “planned economy,” except in the rough sense that the government set goals and exerted pressure. The government simply did not have enough power or information to plan an entire economy. But it could exert pressure, and on a colossal scale. What drove the system was a combination of direct mobilization and modern technologies.

By 1928, Stalin and many others within the Party were both convinced by, and temperamentally inclined towards, the idea of industrializing through a vast and, if necessary, coercive mobilizational drive. The resources were there. They just had to be rounded up. In 1928, Stalin told local officials in Siberia:

Take a look at the kulak farms, you'll see their granaries and barns are full of grain; they have to cover the grain with awnings because there's no more room for it inside. … I propose that:

- you demand that the kulaks hand over their surpluses at once at state prices;

- if they refuse to submit to the law, you should charge them under Article 107 of the RSFSR Criminal Code and confiscate their grain for the state, 25 per cent of it to be redistributed among the poor and less well-off middle peasants.2

On November 7, 1929, after the harvest was in, Stalin published an article called “The Great Turn.” It announced an all-out drive to eliminate the private sector in the countryside by combining peasant farms into large collective farms or kolkhozy, and expropriating the richer peasants, the kulaks. All this was to be done in just a few months.

Party officials who had visited the villages two years in a row to squeeze out grain at rock bottom prices now returned once more. This time, their task was to collectivize all farms before the spring sowing. They organized village meetings at which they tried to encourage the heads of poorer households to pool their resources in collective farms, which would be supplied with buildings, land, and livestock expropriated from the richer farmers, the kulaks. Altogether, about a million kulak households, or 5–6 million individuals, were driven out of their villages, often into labor camps, sometimes in the middle of winter. Within two years several hundred thousand had died.3 John Scott, an American welder who worked in Magnitogorsk in this period, met a former kulak who explained the chaotic and violent processes by which peasants could be classified as kulaks:

the poor peasants of the village get together in a meeting and decide: “So-and-so has six horses; we couldn't very well get along without those in the collective farm; besides he hired as many last year to help on the harvest.” They notify the GPU [secret police], and there you are. So-and-so gets five years. They confiscate his property and give it to the new collective farm. Sometimes they ship the whole family out. When they came to ship us out, my brother got a rifle and fired several shots at the GPU officers. They fired back. My brother was killed.4

The assault of 1.5 million Party members and officials on 124 million peasants succeeded because of the strategic weaknesses of all peasantries – their illiteracy, their geographical dispersion, and the lack of organizational and informational networks to coordinate resistance. They lacked the unity, the discipline, and the organizational ties that bound the Party together, and this allowed the Party to deal with the peasantry not as a class, but village by village. In the 1920s, Russia's peasants lived in 614,000 rural settlements, whose average size was just 200 people, or 30–40 households.5 Expropriation of the kulaks, or “sub-kulaks” (kulak sympathizers) split the villages and deprived them of natural leaders. But the villages did not split as easily as Party members had hoped, partly because the wealthier peasants, like Mongolian lamaseries, provided employment, patronage, protection, and loans to poorer peasants. Entire villages often opposed dekulakization, and army or police units had to be brought in to enforce collectivization. In despair and uncertainty, or just because they could no longer cope, peasants slaughtered half the livestock in the Soviet Union, wiping out about a quarter of the value of the country's agricultural stock.

Collectivization was chaotic partly because officials and police were as confused as the peasants. They had to act fast, under huge pressure, and on poorly thought-through and contradictory orders that they often did not understand. Despite the chaos, by February 1930 the government claimed that half of all peasants had joined collective farms, though most kolkhozy existed only in the paperwork of local officials. Meanwhile the chaos threatened the spring sowing. In January and February of 1930 there were 1,500 anti-government protests or incidents in rural areas, involving a quarter of a million individuals. Protests peaked in March, when there were 6,500 incidents involving perhaps 2 million individuals.6 The sharp increase in protests was prompted partly by an article published by Stalin on March 2, in which he denounced the excesses of local officials. They had become “dizzy with success,” he warned, and some had relied incorrectly on coercive methods. Instead, he insisted, collectivization had to be carried out with the support of the peasantry. Party officials backed off, and many villagers left the recently established collective farms. By July even government statistics suggested that only a quarter of the peasantry and a third of the sown area belonged to collective farms.

But the advance was soon renewed, and a combination of government concessions (contained in a new “Collective Farm Charter”), the removal of potential leaders through dekulakization, and sheer exhaustion, persuaded many peasants to accept collectivization. Yet the worst was still to come. In 1932 and 1933, excessive demands for procurements, the disruption of collectivization, inefficient management, and poor weather combined to create one of the greatest of modern famines. The famine was concentrated in Ukraine, the Volga region, the North Caucasus, and Kazakhstan. Between 4 and 6 million may have died, though some estimates put the casualties higher.7

The writer Mikhail Sholokhov (1905–1984), who had fought in the Civil War and would become a member of the Party in 1932, wrote to Stalin about the worsening situation in his home region of Veshenskaia on the Don. In January 1931, he wrote,

In most kolkhozes cattle are dying on a massive scale … In the Veshenskaya raion, … if things stay the same, if kolkhozes are not provided immediately with fodder, only 20–30% of cattle will remain, and even those will not be capable of work, directly threatening the spring sowing campaign. … Comrade Stalin! The situation in the raions of the former Donetsk district is, with no exaggeration, catastrophic. … But the local press is silent, party organizations are doing nothing to improve the situation by feeding the animals that are still alive.8

A year later, in April 1932, he described the emerging “war” in the villages.

On the farms a real [formennyi] war is being waged by agricultural officials arriving to take cows; they beat whoever gets in their way, mainly women and children; the collective farmers themselves rarely get involved but when they do it can end in murder.9

Next year, in April 1933, he was describing the famine.

In this raion [Veshenskaia], as in other raions, collective farmers and individual farmers are dying from hunger; adults and children have swollen bellies and are eating things no human should eat, beginning with the corpses of animals that have died, and ending with oak bark and the roots of swamp plants. In short, our raion is no different from other parts of our region.10

In the mid-1930s, the government made some modest concessions to the rural population. The 1935 Model Collective Farm Code allowed collective farmers to keep a small plot of land for their private use and to sell what they produced on private plots at free market prices. In effect, these provisions recreated the private gardens of the nineteenth-century peasant usad'ba. Access to a private plot made up for the fact that labor on the kolkhozy generated hardly any income because the government paid so little for the produce of collective farms. As most collective farms coincided with pre-revolutionary communes, the parallels with serfdom were obvious to everyone, particularly once collective farmers were denied the right to travel without the permission of the collective farm director or the local Soviet.11 Some joked bitterly that the initials of the All-Union Communist Party (VKP in Russian) meant “second serfdom” (Vtoroe Krepostnoe Pravo).

By 1936, the government had more or less killed off capitalism in the countryside. Despite the chaos and destruction, collectivization extended the mobilizational reach of the government because officials now dealt with a quarter of a million collective farms or kolkhozy, and smaller numbers of state farms or sovkhozy, each with a government-appointed director, instead of the 25 million individual households of the 1920s. Lazar Kaganovich (1893–1991) bragged that increasing government procurements showed the increasing power of the government over the peasantry (or “the enemy” as he called them).12

But while the government increased its grip on rural produce, the amounts produced on Soviet farms fell. Not until the mid-1950s would harvests regularly exceed those of the late 1920s. So, merely to maintain existing levels of production, the government had to pump resources back into the villages. Tractors were introduced by establishing “Machine Tractor Stations” (MTS), which owned and serviced farm machinery and rented it to collective farms. Though tractors looked like fossil fuels machines, for a time all they did was replace the draught power of horses slaughtered during collectivization.

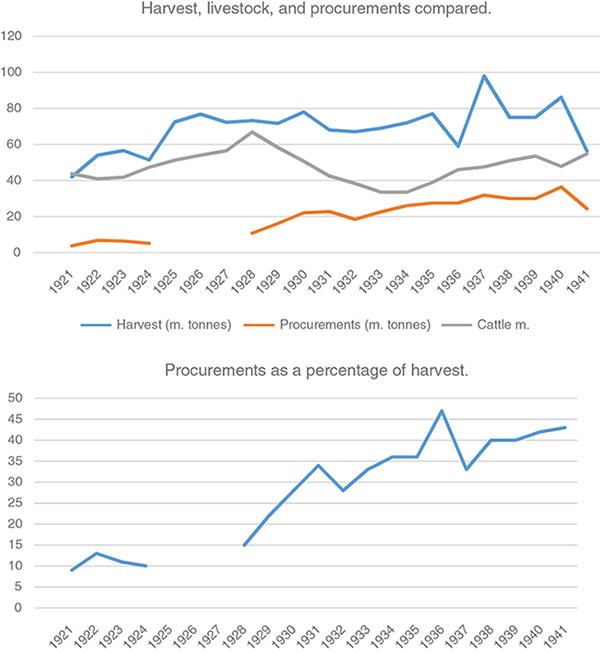

The charts in Figure 14.1 illustrate the difference between growth and mobilization, between stagnating agricultural output and increasing mobilizational power. They suggest that, as a way of increasing output, collectivization was a spectacular failure. Total agricultural output did not increase between 1928 and 1940, while the number of cattle fell. But collectivization succeeded as a strategy of mobilization. In just 10 years, procurements, the share of agricultural produce mobilized by the government, increased from 15 percent to over 40 percent. The Soviet government was now exerting the sort of mobilizational pressure that Muscovite and Tsarist governments had exerted at their height.

Figure 14.1 Two charts showing the meaning of collectivization. Data from Christian, Imperial and Soviet Russia, 273. Reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan.

INDUSTRIALIZATION AND THE BUILDING OF A NEW MILITARY APPARATUS

The government used its increasing mobilizational power to squeeze out the labor, food, and cash needed to industrialize and rearm Soviet society.

The first industrialization plans were produced in the 1920s before the government knew how it would pay for them. In 1928, Gosplan published an ambitious plan for industrial growth, only to have its targets raised and the time for completion shortened by a year. Between 1928 and 1932 total investment doubled, and by 1936 investment was four times the 1928 level.13

How did the government find the labor, cash, resources, and energy it invested in the industrialization drive? Though collectivization reduced agricultural production, it made a vital contribution to the industrialization drive. In 1935, one third of government revenues came from the “turnover tax,” the difference between the low prices the government paid for agricultural procurements and the high prices it charged for agricultural produce in the towns.14 Grain exports, which earned much of the foreign currency needed to pay for foreign technology, increased even during the famines of 1932/3.15 (In Magnitogorsk, early in 1933, John Scott heard complaints about the lack of sugar, to which one worker replied, “We still have to export a lot to get the money to buy rolling mills and other such things that we can't make ourselves yet.”)16

Collectivization also gave the government more control over rural labor. Between 1928 and 1932, dekulakization and voluntary migration from collectivized villages provided 8.5 million of the 11 million new recruits to the urban labor force.17 Recruiters were sent to the villages to lure workers with promises of a glittering life in the city, heroic challenges, and large bonuses. Newspaper campaigns talked up the opportunities and excitement of building socialism. Many peasants, disillusioned with life on collective farms, accepted the challenge. Meanwhile, the productivity of agricultural labor increased even as production stagnated. Per capita output on the farms rose by almost 30 percent between 1928 and 1937, because the agricultural labor force was smaller than in 1928, worked harder, and used more machinery.18

The government did not just mobilize peasant labor. Engineers or recent graduates or people with special skills were moved by government order to huge construction projects. In 1930, the entire staff of Magnitostroi trust, based in Sverdlovsk (former Yekaterinburg), was sent to Magnitogorsk, which was still little more than a huge construction site in the steppes. They were not pleased.

[M]any greeted the [relocation] notice as a personal tragedy. It was very difficult, even pitiful, to forsake the comfort of one's own apartment in the busy and well-known city. And for what? To settle God knows where, in the middle of some deserted mountain of the steppe.19

Many, including kulaks, were mobilized much more brutally. In Magnitogorsk in the early 1930s, 40,000 kulaks lived in a “Special Labor Settlement” surrounded by barbed wire, while criminals lived in a special “Corrective Labor Colony.”20 By the mid-1930s, John Scott reported:

Some fifty thousand Magnitogorsk workers were directly under GPU [secret police] supervision. About eighteen thousand de-kulakized, well-to-do farmers … and from twenty thousand to thirty-five thousand criminals – thieves, prostitutes, embezzlers, who performed unskilled labor usually under guard – these formed the reservoir of labor power needed to dig foundations, wheel concrete, shovel slag, and do other heavy work. The criminals … were usually isolated from the rest of the city. They went to work under armed guard, ate in special dining-rooms, and received almost no pay.21

Slave labor played a significant role in Soviet industrialization, as it had in the Mongol mobilizational system. It was particularly important in large prestige projects such as the building of the White Sea canal between Leningrad and the Arctic, and in remote regions such as northeastern Siberia, where it was hard to attract free labor. By 1929, Soviet planners realized that those in labor camps could “come to the assistance of those economic enterprises which experience an [unskilled] labor shortage,” and they began to incorporate “the work performed by those deprived of liberty” into their production plans.22

Forced labor was not cheap, because it required a vast apparatus of camps, guards, administrators, railways, lorries, and suppliers to move and manage workers who were hostile, unskilled, poorly fed, and of low productivity. But forced labor made brutal mobilizational sense, particularly in the north, where the work was harshest. It helped built the White Sea canal, new sections of the Trans-Siberian railroad known as the Baikal-Amur Magistral (BAM), and it was used to mine gold, silver, and industrial metals along the Kolyma river, or to log timber that could pay for foreign machinery, or to build new industrial cities such as Magnitogorsk in the Urals or Magadan in the far east or Norilsk in the far north. In Stalin's final years, the camps accounted for one third of Soviet gold production, a large share of coal production, and significant amounts of other products such as timber.

But even Soviet leaders wondered at times if free labor might prove more productive and cheaper.23 A former inmate of the camps who tried to calculate the cost of forced labor in food, clothing, accommodation, and the costs of maintaining the guards and camps concluded that

those savings which were actually produced through the forced-labour system were likely to be swallowed up by the very high cost of maintaining the machinery of coercion, which expanded simultaneously with the expansion of forced labour.24

As we have seen repeatedly, such wastage is to be expected from a system dependent primarily on direct mobilization, and more concerned to achieve set goals than to achieve them efficiently.

One measure of the mobilization of human labor for industrialization is the “participation rate,” or the proportion of the working-age population (aged from 15 to 64) working for wages. Between 1928 and 1937, this rose from 57 to 70 percent, which may be faster than in any other rapidly industrializing country.25 Between 1926 and 1939 the urban population rose from 26 to 56 million, and the numbers employed in industry, building, and transportation increased from 6.3 to 23.6 million.26 Those mobilized also worked harder than before. Peasants who migrated to the towns had to learn to work hard all year round, and at the more regular rhythms of industrial production.

Women worked a lot harder. Declining wages forced more women into the industrial labor force, while official feminist propaganda also encouraged women to enter the paid workforce. The percentage of women in wage-earning employment rose from 27 percent in 1932, to 35 percent in 1937, to 53 percent during the war.27 Yet little was done to reduce the domestic burden of women or to encourage men to share in domestic work, and scarcity and queuing increased the time spent on tasks like shopping and laundering. The number of public cafeterias, laundries, and childcare facilities increased, but not fast enough to compensate for the burden of domestic labor. Indeed, such services can be seen as part of the government's mobilization strategy, as they made it just possible for more women to take up the double burden of domestic labor and wage labor.

Paradoxically, the combination of a double or triple burden for Soviet women and significant social services lowered birth rates, which prevented a population explosion and allowed an eventual raising of per capita incomes. It also ensured that grandmothers played a disproportionate role in childrearing, education, and managing households, ensuring the preservation of traditional attitudes, religious habits, and songs and stories.

As our mothers spent their time at the universities and Komsomol meetings, the grandmothers gently rocked our cradles, singing the songs they had heard from their mothers back in the days when the bolsheviks were just being born. Whether Comrade Stalin liked it or not, traditional values were being instilled alongside the icons of the new era.28

Inside Soviet enterprises and factories, workers faced harsh industrial discipline. The government built up the authority and power of managers and directors. Kaganovich insisted that “the earth should tremble when the director walks around the plant.”29 Managers generated pressure that was transmitted down through the system. Grigorii (Sergo) Ordzhonikidze, who headed Vesenkha from 1930, is a paradigmatic example of the “fixer” or “pusher” (tolkach), a type who could also have been found in the entourage of Chinggis Khan or Peter the Great.

Without markets to resolve problems of resource allocation, the Soviet economy relied instead on intervention by bureaucratic authority. Ordzhonikidze's fiendish appetite for work and his ability to find and motivate capable subordinates allowed him to alleviate but not fully eliminate many of the chronic distribution problems the Soviet economy faced. Memoirs of Ordzhonikidze's term at Vesenkha and later at the People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry never fail to mention his prodigious capacity for working late into the night, calling factory directors personally to demand results or to order scarce construction materials shipped to a particularly vital project.30

The role of fixers such as Ordzhonikidze illustrates the importance of sheer pressure in the Soviet mobilizational drive. As Stalin once told Voroshilov during a routine industrial crisis, “We'll put some pressure on and help them adapt.”31

Soviet managerial practices used the time-and-motion ideas of F. W. Taylor, whose methods had impressed Lenin. The government introduced piece-rates, raised work norms, stretched the working day, and cut holidays. Enterprises had immense power over their employees because they did not just pay wages; they also allocated flats and ration cards, so that being fired could deprive you of wages, apartment, and food. In 1930 the government abolished unemployment pay, on the grounds that unemployment no longer existed, and it was indeed true that the government's insatiable demand for labor provided plenty of work.

The government mobilized money with equal determination, by shifting resources from consumption to investment. In 1928, about 82 percent of national income was consumed by households; in 1937 just 55 percent, which represents one of the fastest recorded declines in consumption in the modern era.32 Despite rapid growth in the urban population, the government spent little on new housing. Urban living conditions deteriorated, as more and more people crowded into small, badly built, poorly equipped communal apartments. In Moscow, in 1935, 6 percent of renting families occupied more than one room, 40 percent had a single room, 24 percent occupied part of a room, 5 percent lived in kitchens and corridors, and 25 percent lived in dormitories.33 Conditions in provincial towns were much worse, particularly in new towns such as Magnitogorsk, where for many years most people lived in temporary barracks or even in dugouts or tents, with no clean water, no proper sewerage system, and little heating during the cruel steppe winters. Many tried to survive by keeping cows in the cities. In 1932, an inhabitant of Aktiubinsk in Kazakhstan wrote to Pravda:

Do the local authorities have the right to forcibly take away the only cow of industrial and office workers? … How can you live when the cooperative distributes only black bread and at the market, goods have the prices of 1919 and 1920? Lice have eaten us to death, and soap is given only to railroad workers. From hunger and filth, we have a massive outbreak of spotted fever.34

In 1936, the deputy director of a factory complained about a recent arrival in a factory dormitory who had brought chickens into the dorm.

Perhaps it is possible to bring in chickens, cows and pigs. But then it will be a barn, and not only in the room because the chickens also block up the corridor. It's not necessary to have chickens walking around in the corridor.35

In the early and mid-1930s, the rural population paid for industrialization by surrendering the grain they produced at knock-down prices. The urban population paid through low wages and high taxes on basic necessities, from vodka to matches and salt, as well as sustained pressure to buy government bonds.

But the Soviet system invited collaboration as well as coercing it. The mobilization of both skilled and unskilled labor depended on rewards and opportunities as well as on threats. You could earn bonuses for over-fulfillment, and Alexei Stakhanov, the Donbas coal miner who produced 14 times his planned output with the support of a team of colleagues and some judicious cheating, became a national hero.36 Many, particularly from poor rural backgrounds, found new opportunities in the 1930s, and these help explain the system's ability to generate enthusiastic support from many of its citizens. There was great social mobility so that, despite appalling conditions, many found the material and sometimes the spiritual quality of their lives improved.37 For peasants, the opportunities and glitter of town life offered a sharp contrast to the bleak monotony of life on collective farms. In the second half of the 1930s, conditions stabilized in the countryside and living standards began to rise in the towns. Average real wages rose during the second Five-Year Plan (1932–1937), and the supply of consumer goods increased. Besides, government expenditures on social welfare, on medical and educational services, on crèches, canteens, and laundries, though grossly inadequate, did make a difference. Hundreds of thousands of working-class Russians also moved into positions of privilege and influence they could not have dreamed of in the Tsarist era.

Genuine enthusiasm played an important role in the industrialization drive. It was encouraged by the press, but also by a widespread conviction that Soviet industrialization, for all the chaos and hardship, was creating a new world. As in a battle, even the hardships could be inspiring. John Scott wrote:

In Magnitogorsk I was precipitated into a battle. I was deployed on the iron and steel front. Tens of thousands of people were enduring the most intense hardships in order to build blast furnaces, and many of them did it willingly, with boundless enthusiasm, which infected me from the day of my arrival.38

Propaganda helped. Ever since the October Revolution, the Communist Party had understood the political and ideological power of modern mass media – the press, the cinema, literature, and the radio. In the 1930s, in a partial compromise with the traditional values of its mainly working-class citizens and officials, the government abandoned the radical social and cultural ideas of the early Bolsheviks. It began to support traditional family values, abolished the right to abortion, and made divorce more difficult. History syllabi dropped their focus on class history and told more engaging patriotic stories of great individuals and historical events. Nicholas Timasheff described this return to more traditional values as “the Great Retreat.”39 The combination of Russian patriotism and socialist ideals could generate powerful loyalties. Stalin's comments in a 1937 article celebrating the twentieth anniversary of the revolution would have resonated with many Soviet citizens:

The Russian tsars did many bad things. They plundered and enslaved the people. They waged wars and grabbed territory in the interests of the landowners. But they did do one good thing – they created a huge state that stretches all the way to Kamchatka. We have inherited that state. And for the first time we, the Bolsheviks, have brought together and consolidated this state as a single, indivisible state … for the benefit of the workers.40

The government invested heavily in education. Between 1926 and the late 1930s, literacy rates rose from about 40 percent to about 75 percent. Among the young, they may have risen to 90 percent. Because the government believed women were crucial to the education of the very young, it supported women's education, particularly in rural areas, so that, by the late 1930s, literacy rates among women may have reached 80 percent.41

Introducing new ideas meant suppressing traditional ideas and customs. Officially atheist, in 1924 the government established a “League of Atheists.” After the death of Patriarch Tikhon in 1924 (the Patriarchy had been restored in 1918), the Soviet government did not allow the election of a successor until 1943. In the early 1930s the Soviet government discriminated against all major religions, including Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism. In Siberia in the 1920s, government officials confiscated costumes and drums of shamans. Shamans, in turn, fought back against Soviet medical and educational reforms, which threatened their traditional roles as healers and teachers.

The money, labor, and resources mobilized by the Stalinist government paid for the new technologies of the industrial era. Ideas, innovations, and scientific procedures developed first in the capitalist world played a critical role in Soviet industrialization, because Soviet enterprise managers, like Muscovite merchants, were too hemmed in by the state to introduce major innovations on their own initiative. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union had inherited a modest but rather good tradition of science and technology from the Tsarist era. And within the constraints of the Soviet system, Soviet engineers, scientists, and even managers often showed great creativity as they adapted western technologies to Soviet conditions, often in environments of extreme stress.

The Soviet government mobilized foreign technologies above all for the army. It bought foreign technologies, as its agents “combed European and American military establishments, weapons labs, and technical institutes in order to divine the secrets of up-to-date Western arms.”42 It also engaged in industrial espionage on a huge scale. By the 1930s, Soviet leaders assumed that the best technologies could be found in the USA. The Gorkii car plant was modeled on Ford's River Rouge works, and the iron and steel factories of Magnitogorsk were modeled on the United States Steel Works of Gary, Indiana, and designed by Arthur McKee and Co. of Cleveland, Ohio, specialists in building blast furnaces.43 In the early 1930s, the Soviet government spent huge amounts on research and development, with some spectacular results, particularly in military technology. Soviet designers sometimes improved significantly on their original models. Soviet airframes, for example, were of the highest quality and the Soviet Union was the first country to produce polybutadiene synthetic rubber.

By the late 1930s, Soviet factories were making some of the best tanks in the world. The process began with the reverse engineering of French tanks designed by Renault and captured during the Civil War. In late 1929, the Politburo sent a government mission abroad with direct orders from Stalin to (in Voroshilov's words) “take all measures, spend the money, even large amounts of money, run people to all corners of Europe and America, but get models, plans, bring in people, do everything possible and impossible in order to set up tank production here.”44 In 1930, the mission returned with American and British designs that would provide the basis for the Soviet T-34, T-26, and T-27 tanks. In February 1932, Ordzhonikidze was put in charge of Soviet tank production. Soviet tanks ran on diesel rather than gasoline, which proved important in World War II because captured supplies of Soviet diesel oil were useless for German tanks.45

The systematic adaptation of foreign technologies to mobilize Inner Eurasian resources is a pattern we have already seen in the Mongol era, with the spread of gunpowder technologies to Muscovy, and during the industrialization drive of the nineteenth century. Alexander Herzen once imagined a peasant revolution creating a Chinggis Khan armed with the telegraph, and Trotsky is supposed to have described Stalin as Chinggis Khan with a telephone. Whoever originated it, the metaphor is precise. Radios, tanks, and nuclear power were to Stalin what writing, siege engines, and cannon were to Chinggis Khan: expensive but formidable technologies that could be bought, adapted, and used by a sufficiently powerful mobilization system.

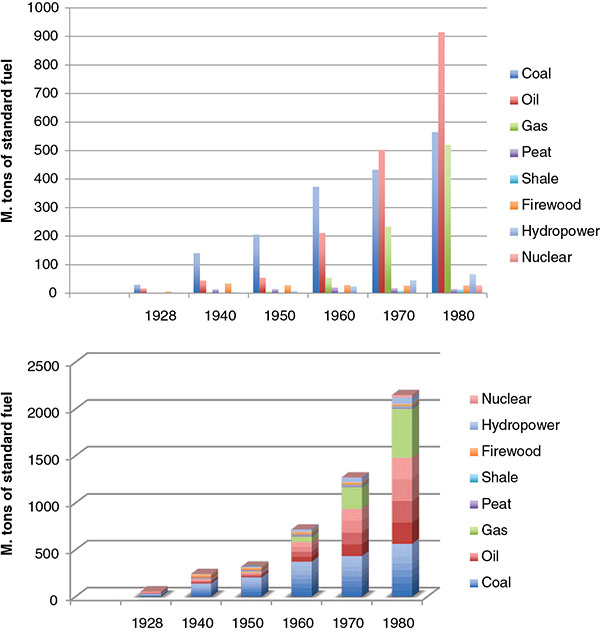

Foreign technologies were particularly important in helping unlock the Soviet Union's vast supplies of energy. Today, the Russian Federation is the leading producer of hydrocarbons in the world, but the remote location and poor quality of many energy sources meant that exploiting them was difficult and expensive.46 Table and the two graphs in Figure 14.2present the same data in different ways to illustrate the importance of different fossil fuels to the Stalinist industrialization drive.

Table 14.1 Soviet fuel and energy production and consumption, 1928–1980

| Date | Coal | Oil | Gas | Peat | Shale | Firewood | Hydropower | Nuclear | Total energy | Apparent consumption |

| 1928 | 29.8 | 16.6 | 0.4 | 2.1 | n.a. | 5.7 | 0.2 | 0 | 54.8 | 50.9 |

| 1940 | 140.5 | 44.5 | 4.4 | 13.6 | 0.6 | 34.1 | 3.3 | 0 | 241 | 243.3 |

| 1950 | 205.7 | 54.2 | 7.3 | 14.8 | 1.3 | 27.9 | 7.5 | 0 | 318.7 | 328.7 |

| 1960 | 373.1 | 211.4 | 54.4 | 20.4 | 4.8 | 28.7 | 23.8 | 0 | 716.6 | 665.5 |

| 1970 | 432.7 | 502.5 | 233.5 | 17.7 | 8.8 | 26.6 | 45.6 | 1.3 | 1267.4 | 1113.8 |

| 1980 | 565.2 | 915 | 519.8 | 15 | 13 | 27 | 67 | 27.2 | 2149.2 |

All units in “million tons of standard fuel,” the common denominator in Soviet energy accounting: 1 ton of standard fuel = 7 × 10 ↑ 9 calories.

Source: Campbell, Soviet Energy Technologies, Table 1.1. Reproduced with permission of Indiana University Press.

Figure 14.2 Two charts showing total Soviet energy production, 1928–1980, and relative contribution of different fuels. Based on Campbell, based on Soviet Energy Technologies, 10. Reproduced with permission of Indiana University Press.

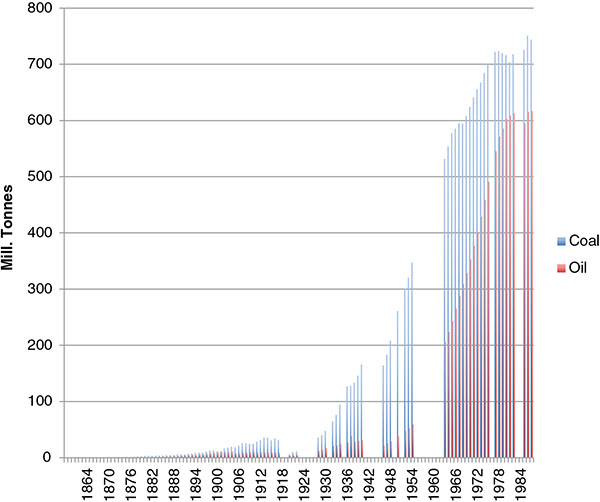

The first thing these figures show is that total energy production in the Soviet Union multiplied by more than 4.5 times in the first 12 years of industrialization, by almost 6 times in just over 20 years, and by about 40 times in the half century between 1928 and 1980. Coal production alone rose by almost 7 times during the 20 years covered in this chapter, while oil production tripled. Fossil fuels and hydropower brought the Soviet Union into the electric age, as electricity production rose from 3.2 to 31 billion kilowatt hours in the decade before the war.47 But during the first Five-Year plans, coal was king. Between 1929 and 1940 the Soviet Union opened more than 400 new mines.48 They played a vital role in industrialization, partly because almost 200 different chemical products are based on coal. Figure 14.3 (which uses slightly different data from Figure 14.2) highlights the sharp increase in the use of fossil fuels from the 1930s, by tracking their production over more than a century. The Soviet Union really committed to fossil fuels only during the first Five-Year plans.

Figure 14.3 The Soviet Union enters the fossil fuels era: coal and oil production in Russia, 1859–1987. Note that measuring by total weight underestimates the increasing importance of oil, which is a more concentrated source of energy. Table 14.1 shows oil overtaking coal by 1970 because it gives standardized measures of energy production. Data from D'iakonova, Neft’ i ugol’ v energetike tsarskoi Rossii, 165–167.

These graphs also highlight the late arrival of the other major fossil fuels: oil and natural gas. Though important in the Stalin era, oil would become dominant only in the second half of the century, along with natural gas. The slow rise of oil and gas reflects, in part, the difficulty and cost of exploiting oil and gas fields in Siberia and Central Asia, far from the heartland, and often in inaccessible regions with high transportation costs.

THE STALINIST MOBILIZATIONAL MACHINE

Without a disciplined elite, the Stalinist system could not have contained the extreme pressures of the industrialization drive. It survived because changes in the 1930s increased the tautness of an already tightly coiled mobilizational machine.

Collectivization and the industrialization drive increased the sense of danger in Soviet society as a whole, but particularly within the Soviet nobility, the nomenklatura. Collectivization's war on the peasantry revived the Civil War mood of a besieged garrison. In 1933, Bukharin told a friend that during the Civil War, he had seen

things that I would not want even my enemies to see. Yet 1919 cannot even be compared with what happened between 1930 and 1932. In 1919 we were fighting for our lives. We executed people, but we also risked our lives in the process. In the later period, however, we were conducting a mass annihilation of completely defenceless men, together with their wives and children … [This experience, he added, had caused] … deep changes in the psychological outlook of those Communists who participated in this campaign, and instead of going mad, became professional bureaucrats for whom terror was henceforth a normal method of administration and obedience to any order from above a high virtue.

The whole process had caused, he wrote, “a real dehumanization of the people working in the Soviet apparatus.”49

Military metaphors flourished in the 1930s, not just because they appealed to Party propagandists, but because they captured the lived experiences of Soviet officials and citizens. Economists talked of production “fronts,” writers of “engineering the human soul” (a phrase of Stalin's), and journalists of “saboteurs” and “traitors.” A world of battlefronts, of “us” and “them,” discouraged independent thought. Wars were launched on ignorance and religion. Within universities, research institutions, newspapers, and schools, the limited intellectual freedoms of the 1920s were curtailed during the first Five-Year Plan. Marxists replaced non-Marxists, textbooks parroted an increasingly rigid official line, and debate disappeared from the newspapers. It was in this atmosphere, in 1932, that the Party established the basic principles of “socialist realism,” and made all writers join a single Union of Soviet Writers. Culture, too, was being mobilized. Socialist realism demanded that cultural work be judged not mainly by aesthetic criteria, but by its contribution to the building of socialism. Aesthetic judgments were made increasingly by censors and politicians rather than by artists or writers.

Many remained loyal to the Party because it offered the only path to privilege. Elite privileges multiplied in the early 1930s. In 1931 Stalin officially attacked “egalitarianism,” arguing that the best workers and officials deserved higher wages and privileges. Party officials were the first to get train tickets or hotel reservations or apartments or scarce consumer goods. Officials’ importance in the new hierarchy depended on the importance of the organizations they worked for, so police and Party officials usually went to the front of the queue, followed by officials from the army, heavy industry then light industry, union organizations, and educational organizations.

In Magnitogorsk, a special suburb was built for foreign specialists, as in nineteenth-century Yuzovka. It was known as Amerikanka, but its name changed to Berezka when Soviet bosses moved in. In a city where many still lived in tents and dugouts (Figure 14.4), Berezka had large, independent cottages with indoor toilets and special restaurants. Avraamii Zaveniagin, the city's director in 1933, built several large houses for himself and his close colleagues, using American designs to create a suburb modeled on Mount Vernon in Washington, DC. It was enclosed with walls and protected by armed guards.

Along with the factory director on the new street lived the city party secretary, the chief of the Magnitogorsk security police … the factory's chief engineer …, the chiefs of various shops, the chief engineer of the mine, and the factory's chief electrician (the latter two were valued “prisoner” specialists in exile).50

Figure 14.4 Tent city, with Magnetic Mountain in the background: Magnitogorsk, winter 1930. Kotkin, Magnetic Mountain. Reproduced with permission of University of California Press.

For such people, the rhetoric of working-class power had real substance.

In the early 1930s, the multiple dangers of war with the peasantry, the metaphorical war for industrialization, and the prospect of future wars with capitalist rivals combined to reinforce the cohesion, power, and authority of the Party and its leaders. In 1933 a correspondent told Trotsky that even the surviving old Bolsheviks, though they hated and feared Stalin, would often add that, “If it were not for that (we omit their strong epithet for him) … everything would have fallen to pieces by now. It is he who keeps everything together.”51 On his last trip abroad in 1936, Bukharin told the exiled Mensheviks, Lydia and Fedor Dan, that Stalin was “a small, wicked man … no, not a man, a devil.” But he added,

He [Stalin] is something like the symbol of the party. The rank-and-file workers, the people believe him. We are probably responsible for it ourselves … and this is why we are all … crawling into his jaws knowing for sure that he will devour us.52

Such thinking paralyzed Stalin's opponents. But in the early 1930s there were still limits to Stalin's power. In 1932, when Stalin heard of an internal Party document proposing that he be removed from power, he demanded the execution of its author, an ex-partisan commander, M. N. Riutin (1890–1937). The Politburo opposed him and he had to settle for Riutin's imprisonment instead. In the early 1930s, Stalin's power was still based largely on the Party, and that limited his power.

But in the mid-1930s, his lieutenants let Stalin escape even these modest checks on his power. In December 1934, a disgruntled communist, Nikolaev, murdered Sergei Kirov (1886–1934), the leader of the Leningrad party, in his headquarters at Smolny, from where the October Revolution had been launched 17 years earlier. There is no evidence for Khrushchev's suggestion that Stalin ordered Kirov's murder, but Stalin did exploit the assassination skillfully to increase the sense of danger and enhance his own power. On his personal authority, he issued new orders for dealing with terrorism. The so-called Kirov decrees created special tribunals to try suspected terrorists, ordered terrorist cases to be dealt with within 10 days, denied the accused defense counsel, denied any right of appeal in terrorist cases, and required that death penalties be carried out immediately after sentencing. Stalin's decree was published in Pravda before it was discussed by the Politburo. Two days later, the Politburo lamely endorsed this judicial revolution, effectively conceding that Stalin's personal authority now exceeded that of the Party. The Kirov laws provided the legal justification for the purges of the late 1930s, and survived until Stalin's death in 1953.

Much of the muscle of the Stalinist system was provided by its police agencies. The first Soviet police institution, the Cheka, was created just after the October Revolution. In 1921, the Cheka was replaced by a smaller and less powerful institution, the “State Political Administration” (GPU). In the late 1920s, the government increased the size and powers of the secret police, and in 1927, Stalin demanded that GPU agents be placed in all government offices and army units. He used the GPU during the procurement campaigns and in his conflicts with Party rivals, who were subject to police harassment and arrest once expelled from the Party.

The power and reach of police organizations grew rapidly after 1929. An expanded and better-funded GPU supervised the deportation of kulaks and their families during the collectivization drive. In 1930, a new organization was created to supervise the labor camp population, which grew from 30,000 in 1928 to 300,000 in 1930 and more than 500,000 by 1934.53 This was GULAG, or the “Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps,” the organization that would manage the vast system of some 476 labor camps that emerged in the Stalin era.54 In 1934, the secret police and GULAG were absorbed within an expanded “People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs,” the NKVD. For the next 20 years, this huge organization managed the vast machinery of internal coercion. Nevertheless, we should not exaggerate its power or size. In the mid-1930s, there were only half as many police of all kinds as there had been at the end of the Tsarist era.55

The Kirov laws allowed Stalin to break one of the few remaining limits on his power: the taboo against using the secret police against Party members. Previously, Party members had normally been protected from police interference. The new laws effectively placed Stalin's personal decisions beyond any formal legal or institutional constraints, including the Party. Whereas previously political authority had flowed primarily through the Party apparatus, now Stalin or his private Secretariat could issue orders more or less at will, through any channel he chose, including the secret police.

The independence of the Party declined precipitously. Party Congresses had met annually in the 1920s. In the 1930s they became rare and perfunctory. After 1934, only two more met in Stalin's lifetime, in 1939 and 1952. In 1938, formal Politburo meetings were replaced by ad hoc meetings of Party, government, police, or military officials, summoned on Stalin's personal authority. The key figures of the leadership were now the “secret five”: Stalin, Molotov, Voroshilov, Mikoyan, and Kaganovich, together with a number of other loyal followers, who had gathered around Stalin during the Party conflicts of the 1920s and in the early 1930s.56 In May 1941, Stalin became the head of Sovnarkom, the Committee of Ministers, while keeping his previous post as General Secretary of the Party. This put him at the head of the two key drivers of the Soviet polity.57 Not even his closest and most experienced loyalists could seriously challenge Stalin from the mid-1930s; indeed, they were as vulnerable to arrest as any other Soviet citizen. What had been a Party dictatorship became a personal dictatorship, as there was no longer any point at which major decisions could be resolved below Stalin himself.

Between 1936 and 1939, there took place a massive purge of the ruling elite, reminiscent, in its scale and brutality, of the oprichnina of Ivan the Terrible.58 Stalin's sponsorship of Eisenstein's film Ivan the Terrible suggests that he understood the parallels. The most visible signs of the purges were a series of show trials, organized with great theatricality in 1936, 1937, and 1938. They subjected former leaders of the October Revolution to public humiliation before condemning them to death. Victims included Stalin's closest Bolshevik comrades, such as Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin, and Rykov. They also included military and political leaders of the Civil War, such as Marshal Tukhachevskii, the leader of the Red Army who did much to reform the Soviet army in the early 1930s, and two leaders of the NKVD, Yagoda and Ezhov. Ezhov's arrest and execution in 1939 marked the end of the most violent phase of the purges, though low-level purges continued for the rest of Stalin's rule.

As Oleg Khlevniuk has shown on the basis of archival materials released in the 1990s, there can now be no doubt about Stalin's personal role in the purges. He really did believe his opponents formed a “fifth column” that threatened the entire Soviet project, and he personally signed thousands of death warrants.

[W]ithout Stalin's orders, the Great Terror simply would not have taken place, and the mass repressions … would have remained at the normal or slightly elevated level that was seen in the mid-1930s and again from 1939 until Stalin's death.59

The purges were driven partly by Stalin's increasing paranoia, but also by the very real threat of war. The Soviet Union was born in war and civil war, and members of the Soviet elite knew how many dangerous enemies they had inside and outside the country. In the late 1930s, the threat of German or Japanese attacks increased. But the government feared attacks from within as much as attacks from abroad. In a speech to the Central Committee plenum of early 1937, Stalin said,

Winning a battle in time of war takes several corps of Red Army soldiers. But reversing that victory at the front requires just a few spies somewhere in army headquarters or even division headquarters, able to steal the battle plans and give them to the enemy. To build a major railway bridge would take thousands of people. But to blow it up, just a few people would be enough.60

During the Spanish Civil War, between 1936 and 1939, Stalin interpreted the failures of the Soviet-backed Spanish Republican armies as daily proof of these internal dangers. Many years later, in his memoirs, Kaganovich still described the 1937 purges as a pre-emptive strike against a dangerous Fascist “fifth column” inside the country.61 But the government's paranoia also arose from the difficulty of getting real information. Not only was the Stalinist government short of officials and police, it was also short of real information because its methods ensured that most officials hid the truth from their superiors most of the time. One scholar has written that: “Under Stalin's dictatorship, the Soviet state was basically blind.”62

Below the surface of the purges, as the government flailed around in search of real or imagined enemies, a vicious pre-emptive war killed or imprisoned millions. Proportionately, the elite suffered most. By 1939, at least 200,000 Party members had been executed, and over 65 percent of the army's high command. At lower levels, relatives and friends of victims suffered, as well as many totally innocent people, some the victims of personal quarrels, some simply caught up in the cogs and flywheels of the Stalinist mobilizational machine. Solzhenitsyn reports a case from Novocherkassk of a woman who visited the local police to ask what she should do about a child whose parents had been arrested, and was herself arrested to fulfill the NKVD's latest quota for arrests.63 The government deliberately whipped up paranoia about internal enemies, and encouraged denunciations on suspicion.

Driving the purges were specific orders to the NKVD to remove “anti-Soviet elements” and members of suspect nationalities. The orders assigned local quotas for arrests, imprisonment, and executions. Having received their quotas, local NKVD officials would summon meetings of local officials and hand out their own quotas, mostly based on the large police files of “anti-Soviet elements.” Those arrested were often tortured to obtain confessions about other potentially anti-Soviet elements.64 According to KGB archives, over 780,000 people were executed between 1931 and 1953, the vast majority in 1937 and 1938. However, there can be little doubt that many deaths went unrecorded, so this counts as a low estimate.65 The prison camp population rose from 500,000 in 1934 to about 1.2 million in 1937 and almost 2 million in 1941.66 In all, some 8 million people may have spent some time in the camps before 1940.67 Conditions in the camps were so appalling that annual death rates of 3.5–7 percent were normal, and in some years, such as 1939 and during the war, as many as 10 percent of inmates may have died each year.68 However, by any calculations, the purges did not kill nearly as many people as the collectivization famines of 1932–1933.

Like Mongke's purge of Guyug's supporters in 1252, this was not a war of conquest but an elite blood-letting, designed to eliminate dissidents and temper a new leadership group even as it caught up many innocent victims. Party members themselves understood its harsh logic. Lev Kopelev, who was arrested in 1945 while serving with the army in Germany, wrote that in prison, his support for Stalin never wavered. “[I] believed that the generals, the men of the N.K.V.D., the judge and the jailers were all blood of my blood, bone of my bone; that we were all soldiers in one army.”69 If anything, the chaos and the stresses of the 1930s enhanced the ruling elite's sense of unity and discipline. As Moshe Lewin put it:

The creation of a hierarchical scaffolding of dedicated bosses, held together by discipline, privilege and power, was a deliberate strategy of social engineering to help stabilise the flux. It was born, therefore, in conditions of stress, mass disorganization, and social warfare, and the bosses were actually asked to see themselves as commanders in a battle. The Party wanted the bosses to be efficient, powerful, harsh, impetuous, and capable of exerting pressure crudely and ruthlessly and getting results, “whatever the cost.”70

Sheila Fitzpatrick has emphasized another aspect of the purges: they made room for a new generation of leaders, totally loyal to Stalin. By 1939, and largely because of the rapid turnover of personnel caused by the purges, many of the vydvizhentsy, the working-class experts trained in the late 1920s, reached the upper ranks of the Party and government. Their youth, their limited formal education, their Civil War experiences, and their relatively impoverished backgrounds ensured that they would make tough, loyal, energetic, and disciplined subordinates.

Aleksei Kosygin (1904–1980) is representative of the entire generation.71 Born in the first decade of the century, he joined the Red Army during the Civil War, attended a technical college in the early 1920s, worked in cooperative organizations in Siberia, and joined the Party in 1927. In 1931, as one of the vydvizhentsy, he was sent to the Leningrad Textile Institute. When he graduated, in 1935, he rose fast. By 1937 he was director of a textile factory; by 1938 he headed the executive committee of the Leningrad city Soviet; and in 1939, at the age of 35, he became People's Commissar (Minister) for light industry for the entire Soviet Union. He would stay at the top of the system until his death in 1980. Nikita Khrushchev was another representative of this generation. Lazar Kaganovich, though not strictly a vydvizhenets, as he rose to power through the Party Secretariat, was perhaps the last survivor from this generation. He was born in 1893 to a poor Jewish family from Chernobyl in Ukraine, and died in July 1991, just six months before the collapse of the Soviet Union.72 In 1925, he became first secretary of the Ukrainian party, and played an active role in suppressing resistance to collectivization. In the 1930s, he managed the building of the Moscow subway, and subsequently managed the railway system and heavy industry.

As Sheila Fitzpatrick has shown, members of Kosygin's generation would shape Soviet history from the 1930s until the system collapsed in 1991. They included Leonid Brezhnev (1906–1982), Nikita Khrushchev (1894–1971), Dmitrii Ustinov (1908–1984), and Andrei Kirilenko (1906–1982). In the early 1980s, 50 percent of Politburo members came from this group. Those who rose to the top during the 1930s were to Stalin what Chinggis Khan's keshig had been: a loyal and disciplined body of followers who owed everything to their leader, who understood mobilization, and had the energy, determination, and ruthlessness needed to do whatever had to be done in a time of great danger and spectacular opportunities.

BENEFITS AND COSTS: MOBILIZATION V. EFFICIENCY

Mobilization is not the same as efficiency, and there can be no doubt that the Soviet mobilizational system wasted colossal human, material, and financial resources. As in the mobilizational systems of Muscovy and the steppes, the task of mobilization – finding and deploying enough resources – trumped efficiency – the task of using resources economically. The Stalinist industrialization drive showed that the same mobilizational rules could apply also to the building of a modern fossil fuels-driven industrial society. But the human, material, and financial waste really was colossal. John Scott wrote of his time in Magnitogorsk:

Semi-trained workers were unable to operate the complicated machines which had been erected. Equipment was ruined, men were crushed, gassed, and poisoned, money was spent in astronomical quantities. The men were replaced by new ones from the villages, the money was made good by the State in government subsidies, and the materials and supplies were found somehow.73

The army complained that 40 percent of machine guns produced in 1930 had to be returned to the factories for retooling. No wonder. The factories often got around inspectors by wining and dining them lavishly. In 1933, a Vesenkha official reported that

at Factory #8 of the Artillery-Arsenal Association and at the Tula Armaments Factory a system was established of entertaining visiting representatives of the … Commissariat of Heavy Industry, and the NKVM [Commissariat for Military and Naval Affairs] with meals, dinners, and drinking bouts on business trips, [creating] the danger that as a result the army might receive and [quality-control inspectors] might pass substandard production.74

The official concerned recommended banning the sale of liquor in factory restaurants, and Ordzhonikidze backed him.

The important question for Soviet agencies and managers was: did they have enough labor, energy, and resources to get the job done? And the most effective managers and Party bosses generally got what they needed by hoarding resources so that they had reserves of labor, cash, and materials in a crisis. That often got the job done, but at huge cost.

Measuring the scale and efficiency of Soviet industrialization is not easy. Available statistics are not detailed or reliable enough to allow great precision. However, the opening of Soviet archives after 1991 has shown that Soviet statistics, despite an element of propaganda, were not wildly inaccurate. This is not surprising. After all, the statistics used by Soviet propagandists were also used by Soviet economists, managers, and planners. As Joseph Berliner argues, the archives suggest that the western researchers who worked with Soviet-era statistics “had got it largely right.”75

But, however accurate they were, interpreting Soviet statistics is not easy, partly because rapid technological change altered the nature and value of what was being measured. How can one compare the respective values of tractors and horses? It is hard to measure changing output either in physical terms, because the goods themselves changed, or in value terms, because the value of the ruble also changed. As the output of machinery increased in the 1930s, its value fell relative to that of more traditional products, so that calculations based on 1928 prices suggest more rapid industrial growth than calculations based on 1937 prices. Furthermore, prices set arbitrarily by planners and insulation from global markets make value comparisons with other countries difficult. In what follows we will rely on some of the most careful computations of Soviet economic growth in the 1930s.76 Where they reveal very large changes we can have some confidence in them, and for our purposes it is the large changes that are most telling.

In 1928, agriculture still accounted for 48 percent of national income, or slightly less than in 1913; by 1940, agriculture's share of national income had fallen to about 30 percent.77 Industry, construction, and transport together accounted for about 32 percent in 1913, and about 28 percent in 1928. By 1940, they accounted for about 46 percent of national income. Employment figures show an equally significant shift in the relative importance of different sectors. In 1926, about 72 percent of the workforce was employed in agriculture, and 6.3 percent in industry, building, and transport. By 1939, only 48 percent was employed in agriculture, while the numbers in industry, building, and transport had risen to 24 percent.78

Soviet estimates suggest that by 1940 Soviet national income was more than six times as large as in 1913 and five times as large as in 1928.79 These figures set an upper limit to available estimates, and it is striking that they roughly match the increase in energy from fossil fuels. The most influential western estimates, those of Abram Bergson, are lower; they suggest that national income in 1940 was 2.75 times the 1928 level if one uses 1928 prices, and 1.6 times that level using 1937 prices.80

Should we be impressed by these changes? At a time when most capitalist economies were in the doldrums of the Great Depression, the Soviet achievements looked impressive. And whatever the statistics tell us, the Soviet performance in World War II shows that something really did change. By the end of the war, the Soviet Union had been transformed into a modern military superpower.

But, as this suggests, the achievements were concentrated mainly in defense and heavy industry. Indeed, it is only a slight exaggeration to describe the industrialization drive as an “armaments” drive. The entire economy was put on a war footing, particularly after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in September 1931. Industrial production shifted into new areas, of which the most important were armaments, automotive industries, machine tools, and electrification. The number of artillery units produced rose from just under 1,000 in 1929/30 to 15,000 in 1940. In the same period tank production rose from 170 per annum to 2,794, and aircraft production from 899 to 10,565.81 Defense accounted for only 2.6 percent of industrial production in 1930 but for 22 percent in 1940.82 Growth was less impressive in consumer goods industries, and there was no significant growth in agricultural output. Though urban living standards may have improved slightly in the middle 1930s, as a whole real wages probably declined by somewhere between 17 percent and 43 percent between 1928 and 1937.83

Though efficiency was not the primary goal of Soviet industrialization, attempts to measure its efficiency illustrate the dominant role of direct mobilization. To what extent did the industrialization drive depend on raw mobilization of hitherto unused resources, and to what extent on using those resources more efficiently? One very general measure of efficiency is GNP per head, or gross national production divided by population. Calculating this statistic is difficult, but the most recent attempts suggest that, while production per head did not rise at all between 1913 and 1928, between 1928 and 1937 it rose by 60 percent, though it stagnated in the years before the war.84 Between 1928 and 1937, when Soviet rates of growth were fastest, Soviet gross domestic product (GDP, which is more or less interchangeable with GNP) per head rose from about 19–32 percent of the US level, from 29–40 percent of the UK level, from 40–53 percent of the German level, and from 78–108 percent of the Japanese level. Particularly interesting is the comparison with Japan, whose GDP per head in 1913 was similar to that of the Soviet Union, though it had embarked on a capitalist path of industrialization.85

However, estimates of GDP per head are at least in part measures of direct mobilization, as more Soviet workers worked harder than ever before with new types of equipment and increased energy inputs from fossil fuels. Other statistics show better the extent to which mobilization trumped efficiency. If outputs are divided by a measure of inputs in the form of labor, capital, and land, the result is a quantity known as “total factor productivity,” or TFP. The growth of TFP over time offers a notional measure of “that part of economic growth attributable to increased efficiency of technology and resource allocation.”86 While different attempts to estimate changes in total factor productivity between 1928 and 1940 give different results, they suggest the same general conclusion: mobilization was much more important than increasing productivity.87 Improved efficiency counts, on the best estimates, for no more than 24 percent of growth in this period, and probably much less, perhaps as little as 2 percent.88 The productivity of labor may have increased as people worked harder than ever before, but the efficiency with which capital, resources, and energy were used probably declined, as the government solved its most urgent problems by throwing more and more resources at them.

The calculations of Paul Gregory suggest that raw mobilization played a much greater role in the Soviet industrialization drive than in the late Tsarist era. Gregory argues that, “faster input growth ‘explains’ the entire growth differential between the Soviet and tsarist eras.” In both periods, growth was “extensive”; it depended largely on increased inputs. However, “In the tsarist case, 70 percent of growth was accounted for by the expansion of factor inputs; in the Soviet case, a higher 84 percent was accounted for by factor inputs. Although the margin of error in these estimates could be substantial, tsarist productivity appears to have grown faster than Soviet productivity.”89 If correct, these conclusions are surely linked to the fact that the Tsarist industrialization drive used both direct mobilization and market forces to drive growth, while Soviet industrialization depended almost entirely on mobilization.

In other words, it makes sense to regard Soviet industrialization as the result of a massive mobilizational drive. Most technological innovations came from outside the system, which means that when the flow of major innovations dried up, the system was bound to stagnate. Robert Lewis argues that as early as the late 1930s, “The Soviet Union had started to slide into a situation where, across much of the economy, substantial further technical modernization only occurred piecemeal and intermittently in response to central drives to modernize particular areas.”90 As R. W. Davies writes,

By the end of the 1930s it was already becoming apparent that the system which had managed to bring about technological revolution and economic growth from above was incapable, without drastic reform, of encouraging technological innovation from below. [This] deficiency, … ultimately proved fatal for the Soviet economic system.91

THE “GREAT PATRIOTIC WAR” AND ITS AFTERMATH: 1941–1953

During World War I all combatant governments leaned heavily on strategies of direct mobilization, because such strategies work well in the crisis of war, when getting the job done fast was more important than getting the job done efficiently. During the 1930s, Soviet citizens got used to warlike crises, to campaigns, to emergencies, to sudden, unexpected demands, and to danger.

Ever since 1931 – wrote John Scott – the Soviet Union has been at war, and the people have been sweating, shedding blood and tears. People were wounded and killed, women and children froze to death, millions starved, thousands were court-martialed and shot in the campaigns of collectivization and industrialization. I would wager that Russia's battle of ferrous metallurgy alone involved more casualties than the battle of the Marne. All during the thirties the Russian people were at war.92

Industrialization Soviet-style prepared Soviet citizens well for total war. The “Great Patriotic War,” as World War II was called in the Soviet Union, provided the first major military test of the Stalinist mobilizational system.

THE TEST OF WAR

All members of the Soviet Communist Party knew that their achievements would eventually be tested in war. The Great Patriotic War began on June 22, 1941, when the armies of Nazi Germany and its allies crossed the Soviet borders with 5.5 million men, 5,000 planes, 2,500 tanks, and 600,000 motor vehicles, along a 2,000-kilometer front stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea.

How ready was the Soviet Union? Unlike Tsarist Russia in 1914, or the principalities that faced Batu's invasion in 1237, the Soviet Union had a strong, united, and disciplined government. And it turned out, to the surprise of many (perhaps even Stalin), that it could also command the loyalty of most of its subjects. The industrialization drive had laid the foundations for a large defense establishment and the system had exceptional experience of mobilizing in a crisis. It was well designed for the emergency of war.

However, there were also serious weaknesses, some self-inflicted, and it was these that tempted Hitler to gamble on a war of two fronts. The Soviet army had been modernized fast in the 1930s, but the purges had removed many of its best commanders and military engineers, and demoralized those left behind. Many commanders had little experience when the war began, and most Soviet pilots and tank crews had just a few hours of training. Much Soviet military equipment was sub-standard, and the army had little motorized transport; in 1941, the Red Army still used horses to haul much of its artillery and heavy equipment. The chaos of the purge era had slowed production in crucial areas such as oil, iron, and steel. The German General Staff concluded after analyzing the Soviet army's poor performance against Finland in 1939 that it would collapse under a determined assault. Hitler commented, “You have only to kick in the door and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down!”93

Stalin himself made serious blunders. He shared Hitler's assessment of Soviet military prospects, so he did everything he could to postpone a conflict. Apparently on Hitler's initiative, Germany and the USSR signed a non-aggression pact on August 23, 1939. In secret protocols this carved up eastern Europe, giving Germany a free hand in Poland, and effectively restoring to the USSR much of the territory lost in 1918 in the Baltic region and western Ukraine. Germany invaded Poland on September 1, Britain and France declared war on Germany, and the Soviet army marched into eastern Poland and western Ukraine, and forced the Baltic states to sign military pacts effectively placing them under Soviet protection. In 1940, the Soviet Union took control of the Baltic states. Finland was invaded in November 1939 after refusing to sign a similar pact, but the Soviet army soon got bogged down in a brutal border war.

In the newly occupied territories, the Soviet government immediately launched purges of possible anti-Soviet elements. They shot over 20,000 Polish officers at Katyn in April and May of 1940, and removed 370,000 people to the Soviet Union. But up to the moment of Germany's invasion on June 22, 1941, anti-Nazi sentiment was treated as a crime, and the USSR kept supplying Nazi Germany with oil, grain, and other strategic goods, as required under the Nazi–Soviet pact. Stalin even refused to prepare defensive plans, and ignored the accumulating evidence of an imminent attack. As late as June 16, 1941, he described an intelligence report on an attack as “disinformation, not a ‘source’.” Given the huge number of such reports, he may often have been right.94

As a result, the Soviet army was utterly unprepared for the attack when it came. According to the Army Chief of Staff, Georgii Zhukov, when informed of the attack at 3 a.m. on June 22, Stalin insisted the attack was a “provocation by the German military” that did not reflect Hitler's intentions, so he ordered Soviet troops not to open fire.95 Most commanders obeyed, waiting for hours before receiving permission to return fire. German sources reported that 1,500 Soviet planes were destroyed on the ground because they had not received permission to take off.96 Further, as a result of the Nazi–Soviet pact, the Soviet Union had advanced well beyond the fortified lines prepared along its 1939 borders. Economically, too, there were serious failings. Though Soviet planners had talked of relocating industry away from the frontiers, most industry remained around Leningrad and Moscow and in the Ukraine.

These failures help explain the catastrophic defeats in the second half of 1941. The Red Army lost over 5 million killed, wounded, or captured in the first five months of the war, some 60 percent of its productive capacity in crucial areas such as coal, iron, and steel production, and about 40 percent of its rail network.97 German forces occupied the Donbass and Moscow coal fields, halving Soviet coal production.98 By November 1941, Soviet industrial production had fallen to less than half the level of the previous year. By December, German troops were close to Leningrad and Moscow, and had conquered the Baltic, eastern Poland, and the Ukraine. No Russian state had suffered such a catastrophic defeat since the Time of Troubles. The initial collapse was so total that even Stalin himself momentarily despaired.

But Stalin and his government kept their nerve. During the catastrophic first few months, the government began a new mobilization of resources and people that would eventually grind down Germany's armies. Ferocious discipline was imposed within the army, so that retreating armies put up fierce resistance. Stalin spoke to the nation on July 3, admitting something of the scale of the disaster, demanding the creation of militia units and describing some of the measures being taken for defense. On June 24 a special committee was set up to evacuate industries from near the front. By November, over 1,500 entire factories had been dismantled and transported by rail to the Urals, western Siberia, the Volga region, and Central Asia, along with 10 million workers and evacuees.99 By the middle of 1942, most of these factories were producing again. This was an astonishing achievement. The government also built new industries away from the Soviet heartland, in Siberia and Central Asia.

Civilian factories converted to munitions production, and the percentage of GDP devoted to defense rose from about 18 percent in 1940 to an astonishing 70 percent in 1942, after which foreign supplies began to ease the burden, reaching almost 20 percent of Soviet GDP in 1943 and 1944.100 There were remarkable displays of patriotism from soldiers and civilians. Some 420,000 men were mobilized from labor camps in 1941, and most fought bravely and loyally for the Red Army, though the presence in their rear of special units of Smersh’ (“Death to Spies”) with machine guns aimed at deserters helped maintain discipline. Civilians in munitions factories worked long hours on starvation rations. In Leningrad they worked under enemy bombardment. Mobilization for war undermined civilian production so that many people had to grow their own food in allotments, or planted crops in public parks, “laying the groundwork for the dacha socialism of later years.”101

At times, the danger seemed to be of over-mobilization, and in the early months of the war, when the government's slogan was “All for the front!” that danger was significant. Mark Harrison comments, “the civilian economy collapsed, the minimum tolerance limits of society were breached, overworking and undernourishment became widespread, civilian mortality rose, and the infrastructure of war production was undermined.”102 By 1942, the government had learned that it had to take care of the rear, where it would find the reserves of labor, raw materials, and equipment needed to win the war.

The first military successes came when the German armies were halted outside Moscow. They were also checked outside Leningrad, which would endure a 28-month-long siege, during which one third of its population of 3 million would die. The German attack on Moscow was repulsed by a well-planned counter-attack in December 1941. German troops were ill-equipped for the extreme cold of a Russian winter during which even the oil in tank engines froze. They were driven back by fresh troops from Siberia led by Marshal G. Zhukov. Zhukov's defeat of the Japanese army at Khalkhyn Gol in eastern Mongolia in August 1939 had persuaded the Japanese to concentrate their efforts on the Pacific rather than in Siberia, and this ensured that the Soviet Union would have to fight on only one front. The Moscow counter-attack showed that the German blitzkrieg had failed to break the Soviet Union. Given a long war, and the chance to mobilize more resources, the balance of power was bound to shift in favor of the Soviet Union, with its huge reserves of people, energy, and resources. In 1942, Soviet military production began to rise fast.

Hitler, who was aware of his own armies’ shortage of fuel, decided not to renew the attack on Moscow in 1942, despite the advice of his generals. Instead, he sent his armies towards the oil-rich lands of the Caucasus and the Caspian. He had long been obsessed with oil, which he saw as “the vital commodity of the industrial age and for economic power. He read about it, he talked about it, he knew the history of the world's oil fields.”103 In August 1941, he told his generals that the primary goal was not to take Moscow but “to seize the Crimea and the industrial and coal region on the Donets, and to cut off the Russian oil supply from the Caucasus areas.”104