[16]

1950–1991: THE HEARTLAND: A PLATEAU, DECLINE, AND COLLAPSE

INTRODUCTION: GLOBAL PROCESSES

In the second half of the twentieth century, there was an astonishing global economic and technological boom that some have described as the “Great Acceleration.” So rapid was growth, so fast was technological change, and so vast and diverse were human impacts on the biosphere that many scholars see the late twentieth century as the start of a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene. Humans began mobilizing resources on such a scale that they became the most important single force for change on the surface of planet Earth.1

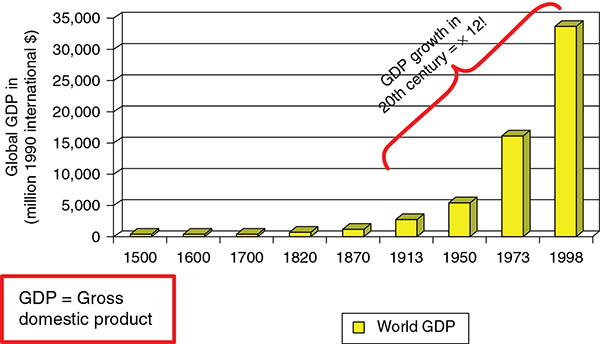

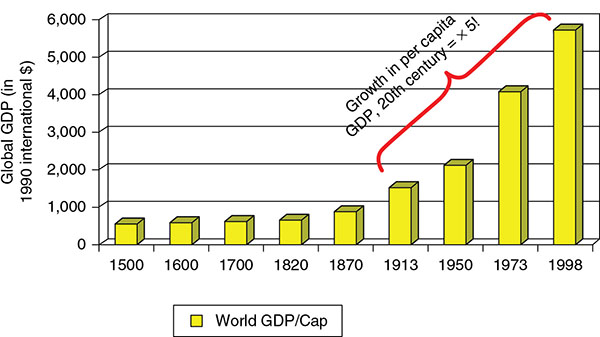

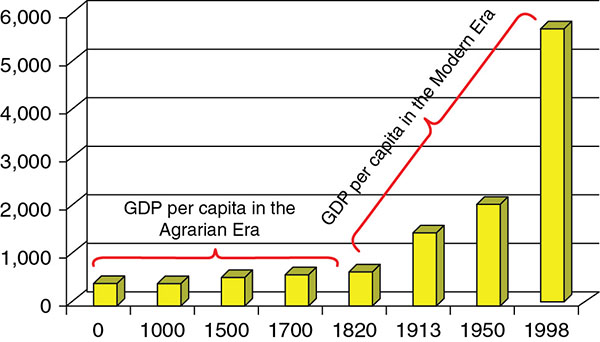

Economic statistics offer a pale reflection of these changes. We customarily focus on economic growth, but that of course is ultimately a measure of the scale on which humans mobilize the animals, the plants, the rivers, the energy, and the minerals of the biosphere. The acceleration was synergized by a new pulse of globalization. Between 1913 and 1950, the total value of international trade had fallen from about 8 percent of world production to just 5.5 percent. Then exports rose to about 10.5 percent in 1973 and to an astonishing 17 percent by 1998.2 Global exchanges spread innovations and stimulated economic growth. In the boom years of the 1960s and 1970s, rates of economic growth were faster than ever before (or after) in human history. Figures 16.1–16.3 illustrate some of the large changes in global GDP and global GDP per capita (the most general measure of increasing productivity) over long periods, to highlight the unprecedented growth rates of the late twentieth century.

Figure 16.1 Global GDP, 1500–1998, based on figures from Maddison, Monitoring the World Economy, 261.

Figure 16.2 Global GDP per person, 1500–1998, based on figures from Maddison, Monitoring the World Economy, 264.

Figure 16.3 Growth in GDP per person over two millennia, based on figures from Maddison, Monitoring the World Economy, 264.

Technological and organizational changes, many pioneered during the wars of the early twentieth century, drove growth. There were innovations in aviation, in health, in agriculture, in communications, and in how governments and corporations managed research, investment, and production. Nuclear power, developed as a result of massive wartime projects to develop nuclear weapons, added to the energy bonanza of fossil fuels and spun off new insights into fundamental physics. Computers, developed originally to help break enemy codes, improved the management of financial systems, manufacturing processes, government bureaucracies, and scientific research and accelerated global exchanges of information. As more countries and regions entered the fossil fuels era, energy was consumed faster than ever before. Figure 10.3 suggests that between 1900 and 1950, global energy consumption increased by about two and a half times, and then by about five and a half times between 1950 and 2000. By some estimates, global GDP multiplied by seven times in the second half of the twentieth century. Never before had humans been so numerous, or mobilized the resources of the biosphere on such a vast scale.

These momentous changes provide the backdrop to the history of Inner Eurasia in the second half of the twentieth century, because they put increasing stress on efficient mobilization of resources. In the Stalin era, low rates of growth in the capitalist world flattered the Soviet economy. In the second half of the twentieth century, faster growth rates in the capitalist world made Soviet growth seem less impressive, and highlighted its inefficiency.

The second half of the twentieth century was also an era of decolonization and imperial breakdown. So weakened were Europe's major powers by the end of World War II that they could no longer defend the global empires they had acquired from the late nineteenth century. Decolonization created new, independent nations, all of which had to find their way in a rapidly changing world. And they soon found that disparities in wealth, power, and industrial development exposed them to new forms of exploitation as they, too, tried to enter the world of fossil fuels. In Inner Eurasia, however, there was no decolonization after World War II. Here, decolonization would begin only at the end of the twentieth century, and would take distinctive forms.

A third crucial feature of the late twentieth century was the Cold War. Though happy to purchase western technology, the Soviet Union cut itself off from the capitalist world commercially, politically, and ideologically. Two world coalitions emerged, both of which would be courted by weaker or smaller powers, many of them former colonies. The two blocs were technological, ideological, economic, and military rivals, and their rivalry would dominate the second half of the twentieth century. Ultimately, the rivalry was between different mobilizational strategies, and in the middle of the century the Soviet Union looked like a mobilizational success. By the mid-1960s the Soviet Union had nuclear weapons, the missiles needed to deliver them, and the largest armies in the world. The first human space flight, by Yuri Gagarin on April 12, 1961, offered a stunning demonstration of Soviet technological and military prowess. The Soviet Union achieved military (though not yet economic) parity with the USA, the world's first modern superpower. With the development of nuclear weapons, both superpowers now had the power, if they chose, to launch attacks so destructive that they would have ruined much of the biosphere within just a few hours.

The Soviet system had clearly got some things right. And after the death of Stalin, the turbulence of the first half of the century gave way to a period of stability, during which many Soviet citizens felt that they were finally reaping the rewards of industrialization. That is why so many other countries were tempted to borrow from the Soviet formula for industrialization.

Then, in the 1970s, signs began to accumulate that the system was running down. Like the Russia of Catherine the Great, the Soviet system seemed to have reached a mobilizational plateau. As mobilizational pressure declined, accelerating growth rates in the capitalist world exposed the limitations of a strategy that was good at mobilizing resources, but less good at using them efficiently, because it had dispensed with the market driver of growth and innovation.

This chapter describes the Soviet mobilizational system in its most successful era, and in the era of decline. The system's weaknesses were hidden at first by the discovery of vast new stores of fossil fuels in its Inner Eurasian hinterlands. These kept the machine running as efficiency declined. Lulled into complacency, the Soviet nomenklatura settled into lives of power and privilege, while the Soviet mobilizational machine began to splutter and wheeze, and innovation stalled. In the mid-1980s, Soviet leaders attempted a radical overhaul, but succeeded only in weakening the machine further, just as the Great Reforms of the nineteenth century had destabilized the Tsarist system. But this time, events moved so fast that in 1991, just six years after reforms began, the Soviet mobilizational system fell apart, collapsing as suddenly as the Mongol Empire after the death of Khan Mongke.

THE SOVIET HEARTLAND, 1953–1991: A MOBILIZATIONAL PLATEAU

In the middle of the twentieth century, Soviet citizens born 50 years earlier had lived through changes as astonishing as those experienced by the followers of Chinggis Khan. The Soviet Union was now a superpower, and after the communist conquest of Inner Eurasia's other superpower, China, almost half the world's population lived under communist regimes. It began to seem that the mobilizational systems that dominated Inner Eurasia might end up dominating the world.

DESTALINIZATION: CHANGES IN THE POLITICAL SYSTEM

Stalin's death, on March 5, 1953, came as a profound shock. Millions of Soviet citizens had revered and feared Stalin in equal measure, and most could not imagine a future without him. The poet Yevgenii Yevtushenko remembered his own reaction:

I found it almost impossible to imagine him dead, so much had he been an indispensable part of life. A sort of general paralysis came over the country. Trained to believe that Stalin was taking care of everyone, people were lost and bewildered without him. The whole of Russia wept. So did I. We wept sincerely with grief and perhaps also with fear for the future.3

None of Stalin's lieutenants controlled all the threads from which Soviet policy was woven. And like Timur, Stalin did not nominate a successor. With a strong central government, but no obvious successor, some form of collective leadership was unavoidable.

In the days and weeks after Stalin's death, the survivors of Stalin's inner circle maneuvered cautiously in a dangerous, foggy, and unpredictable environment, fearing that the colossal pressures under which the system operated might blow it apart. Khrushchev admitted in his memoirs, “We were scared – really scared. We were afraid the thaw might unleash a flood, which we wouldn't be able to control and which would drown us.”4 Their sense of personal and collective danger had intensified just weeks before Stalin's death, when he announced the discovery of a plot to overthrow the leadership – the “Doctors’ Plot” – which was led by elite Kremlin doctors. Members of Stalin's immediate circle feared this was the start of a new purge that would sweep them all away. They were jittery, and their fears would soon be heightened by prison camp mutinies in the Vorkuta region, and an uprising in East Berlin in June.

Their nervousness explains some skittish policy decisions taken just after Stalin's death that look like attempts to release pressure by appeasing the population. On March 27, an amnesty for non-political prisoners in the camps freed more than a million prisoners. Those released included former members of the Soviet ruling elite, such as Molotov's wife, Zhemchuzhina (personally returned to Molotov by Beria), and Mikoyan's son.5 On April 1, prices were slashed on basic consumer goods by an average of 10 percent, and wages were raised by 8 percent during 1953. The new leaders increased planned output for consumer goods, and in 1953, for the first time since the 1920s, the production of consumer goods rose faster than that of producer goods. In August, the government reduced taxes on the private plots of collective farmers, and increased the prices it paid for procurements from collective and state farms. Production rose immediately on private plots. These shifts – pale reminders of the “retreats” of 1921 and 1934 – had an immediate effect on the popular mood. By agreeing to an armistice in the Korean War in July, the new leadership also lowered international tensions.

With Stalin gone, institutions mattered once more. Most members of the new leadership felt threatened by the NKVD (the Ministry of Internal Affairs) and its leader, Beria, and they began to chip away at the NKVD's power. Just weeks after Stalin's death, the NKVD announced that there was no foundation to the “Doctors’ Plot.” On April 10 the Central Committee condemned “violations of legality” by the security organs. Beria, an obvious candidate for the leadership, was now as exposed as Trotsky had been after the death of Lenin.

In his memoirs, Khrushchev claimed credit for the delicate maneuvers that led to Beria's arrest on June 28 at a meeting of the Presidium (as the Politburo was called between 1952 and 1966). Beria controlled the Presidium bodyguard, so senior military commanders, including General Moskalenko, the air defense commander, and Marshal Zhukov were invited to attend the decisive meeting and given permission to carry their weapons as they waited in an anteroom. Khrushchev describes what followed.

We arranged for Moskalenko's group to wait for a summons in a separate room while the session was taking place. [When Malenkov pressed a button to give the prearranged signal, the generals entered the room.] “Hands up” Zhukov commanded Beria. Moskalenko and the others unbuckled their holsters in case Beria tried anything.6

The operation went smoothly and Beria's police bodyguard did not try to prevent his arrest. After a brief trial, he was executed in December.

These changes began to lower the extreme tensions of high Stalinism. As in the 1920s, changes in the balance of power within the Soviet system were shaped by disputes over the succession. With Beria gone, the secret police now had no representative in the Presidium, and early in 1954, the new leadership broke up the NKVD's vast empire. The ordinary police stayed within a shrunken Ministry of Internal Affairs, while the secret police were placed under a new party committee, the “Committee of State Security” or KGB, headed by a Khrushchev loyalist, I. A. Serov. GULAG, the labor camp administration, was effectively abolished in 1957, when it was placed under the Ministry of Justice. The number of political prisoners fell sharply in the 1950s, and by the 1970s, Amnesty International estimated that there were no more than 10,000 political prisoners in a total prison population of almost 1 million.7

With the secret police cut down to size, two institutions now dominated the system: the Party and the government apparatus headed by the Council of Ministers. Stalin himself had often bypassed the Party in recent years, which may explain why Malenkov, when given the choice in March 1953 between a Party position and a position in the government apparatus, chose to become Chairman of the Council of Ministers. This left Khrushchev as the leading figure in the Party apparatus, and it soon became clear that, with Stalin dead and the secret police weakened, the Party and its Secretariat once again enjoyed the strategic advantages that had helped bring Stalin to power in the 1920s. Once again, it was the only Soviet institution with influence over officials within all the other governmental structures of Party, police, government, and army.

Power flowed back to the Party, as if by a law of Soviet political gravity that had been temporarily suspended by Stalin. In September 1953, Khrushchev became the First Secretary of the Party's Central Committee. He immediately began to fill key institutions with members of his own informal political networks. By 1956, about one third of Central Committee members had served under Khrushchev in the Ukrainian or Moscow Party machines.

Khrushchev maneuvered skillfully. In 1954, he resisted Malenkov's populist tactic of switching investment from heavy industry to consumer goods industries. This earned Khrushchev support within the powerful military and heavy goods ministries. In 1954, he launched the “Virgin Lands” program, whose aim was to increase food supplies by bringing the Kazakh steppes under the plow, while rallying the Party and people behind a grandiose new project.8 (See Chapter 17.)

In February 1955, Malenkov resigned as Prime Minister. Khrushchev now emerged as the dominant figure within the collective leadership. In 1956, he took the unexpected gamble of criticizing Stalin during a secret session of the twentieth Party Congress. He criticized Stalin mainly for his assault on the Communist Party, but Khrushchev's personal bitterness came out in asides excluded from the official transcript. According to one attendee, Khrushchev denounced Stalin as a coward, saying, “Not once during the whole war did he dare go to the front.”9 Khrushchev was not alone in seeking a reckoning with the Stalinist legacy. His “secret” speech was probably drafted by the historian P. N. Pospelov. It praised Stalin's achievements before 1934, implicitly asserting the legitimacy of the one-party state, of the Party's leadership, and of both collectivization and the industrialization drive. But the speech condemned the increase in Stalin's personal power after 1934, and his violent assault on Party cadres during the purges. It also condemned many of his decisions before and during the war. Its main target was not the Party or the system, but Stalin's personal power, his “cult of personality.” The speech praised the Soviet system, while blaming Stalin for its most serious failings and flaws.

Khrushchev's colleagues in the Presidium were appalled. Stalin's personal prestige had legitimized the Soviet system for so long that they feared Khrushchev's criticisms would undermine it. And they were at least partly right. News of the “secret speech” soon leaked out, prompting pro-Stalin demonstrations in Stalin's home republic of Georgia, covert anti-Soviet demonstrations in the Baltic republics, and eventually uprisings in Poland and Hungary. The speech alienated the Chinese leadership and prompted many communists outside the Soviet Union to resign from the Party. In 1957, a majority of Khrushchev's Presidium colleagues voted to sack him.

That should have ended Khrushchev's brief career as Party leader. But his rivals had underestimated the leverage Khrushchev now had through the Party apparatus. The secret speech had appealed to many within the Party, particularly those less close to Stalin. Khrushchev insisted that only the Party Central Committee, which formally elected the Presidium, had the power to sack him. With help from the army and KGB, both now headed by Khrushchev loyalists, members of the Central Committee were flown to Moscow from all parts of the Soviet Union. With Serov, the head of the KGB, in charge of the Kremlin guard, members of the Central Committee demanded a formal meeting of the Central Committee. The Presidium reluctantly agreed, Khrushchev was reinstated, and over the next few months, with the blessing of the Central Committee, he expelled his rivals, finally breaking up the leadership team formed by Stalin since the 1920s. Molotov, Kaganovich, and Malenkov were removed from office, but that was the extent of their punishment. Kaganovich, one of Stalin's toughest enforcers, phoned Khrushchev two days after the Central Committee meeting, begging him “not to allow them to deal with me as they dealt with people under Stalin.”10

By now, Khrushchev enjoyed something like the level of power that Stalin had in the early 1930s. He was undisputed leader of the Party and government, and already the subject of a small-scale cult of leadership. But his power still rested on, and could still be limited by, the Party apparatus. Between 1957 and Khrushchev's removal by the Presidium in 1964, Khrushchev failed (and may not even have tried) to create the type of arbitrary personal power that Stalin had wielded from the mid-1930s. Occasionally Khrushchev took decisions on his own authority that should have been taken by the Presidium or the Central Committee. He may even have tried to outflank the Party apparatus by increasing Party membership and setting limits on the tenure of Party officials. He tried to increase the role of local Soviets in local government and occasionally invited non-Party members to Party Congresses. It is not clear whether these initiatives reflect a genuine commitment to greater democracy within the Party, or a populist attempt to outflank the Party apparatus by mobilizing support at lower levels.

Whatever Khrushchev's intentions, it was unlikely that there would be a return to the type of dictatorial power wielded by Stalin. Stalin acquired his power in a period of extreme crisis, when Party members knew they faced daunting internal and external threats. Now the atmosphere was utterly different. The Soviet Union was a superpower; it had survived World War II; it had a powerful industrial and military establishment; it led a regional defense alliance (the Warsaw Pact), founded in 1955; its scientists had developed an atom bomb by 1949, and an H-bomb by 1953. In 1957, the Soviet Union launched the world's first artificial satellite, proving that it had the missile technology needed to deliver nuclear weapons. These successes raised the prestige of Soviet science, and created optimism in the USSR (and pessimism in the USA) that the socialist system would soon overtake the capitalist system of the USA industrially, technologically, and militarily.

In this more confident atmosphere, Party leaders no longer felt obliged to tolerate autocratic or erratic leadership. Like eighteenth-century Russian Guards regiments, they were willing to risk the occasional coup in the interests of more stable leadership. On October 13, 1964, while Khrushchev was on holiday on the Black Sea coast, the Presidium removed him from office. Khrushchev accepted the inevitable with little protest, and even took some pride in the manner of his removal. His son, Sergei, reported him as saying,

I'm already old and tired … I've accomplished the most important things. The relations between us, the style of leadership has changed fundamentally. Could anyone have ever dreamed of telling Stalin that he no longer pleased us and should retire? He would have made mince-meat of us. Now everything is different. Fear has disappeared, and a dialogue is carried on among equals. That is my service. I won't fight any longer.11

As in eighteenth-century Russia, a more confident leadership offered stability for its elites. Leonid Brezhnev's watchword, “stability of cadres,” captured with precision the new mood of the Soviet nomenklatura. Brezhnev would rise along a similar path to Khrushchev until he, too, became undisputed leader and the focus of a new leadership cult. But his power always rested on the Party apparatus and he ruled as a consensus politician. No longer could the Soviet system generate the extreme elite discipline of the 1930s. And that helps explain why it would never again be able to generate the extreme mobilizational pressure that had powered industrialization and victory in the Great Patriotic War.

CHANGING ATTITUDES AND LIFEWAYS

In the 1950s, Soviet citizens finally began to benefit from the sacrifices of the Stalin era. The ad hoc concessions of the early 1950s were replaced by more systematic concessions that became part of an informal “social contract” between government and people.

The Virgin Lands program set the tone. It was a vast mobilizational effort intended to improve food supplies and living standards. For a year or two it looked like a success. For the first time, Soviet grain harvests rose above the level of 1913: from 82.5 million tons in 1953, to 134.7 million tons in 1958. However, under intense pressure to raise output local officials cut corners and ignored warnings by agronomists about the fragility of steppe soils. By the early 1960s production was declining in almost half of the Virgin Lands. To fulfill its end of the new social contract, the government reacted not by demanding new sacrifices, but by buying food abroad, at the cost of precious reserves of foreign currency. Sixty years earlier, the Tsarist Empire had been a major grain exporter. From 1964, the Soviet Union became a major importer of grain.

Though this was a worrying sign, for most Soviet citizens life got better. Under Khrushchev, wages rose, school tuition fees (reintroduced under Stalin) were abolished, new consumer goods appeared, such as fridges and washing machines, the working day was shortened, and pensions and holiday entitlements increased. Khrushchev also invested in housing, a task Stalin had ignored. In 1957, Khrushchev launched a vast program to build cheap apartment buildings. Though unattractive (they were often described as Khrushchoby, a pun combining Khrushchev with the word ushchoby, or “slums”), the new apartments improved living conditions for millions, and reduced the number of people sharing kitchens and toilets in communal apartments, or kommunalki. These had been a major cause of domestic conflict, as families fought petty guerrilla wars in their corridors, kitchens, bathrooms, and bedrooms.

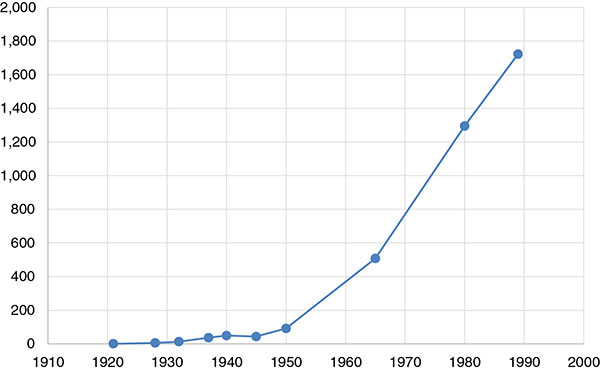

Rough estimates of Soviet consumption levels suggest that by 1950 they had reached about 110 percent of the 1928 level and by 1958 they had reached 185 percent.12 Living standards rose in both the towns and the countryside, making good the promise of a better life for working people after a generation of sacrifice. Improving living standards lent plausibility to Khrushchev's boast that the Soviet Union would catch up with and overtake the capitalist world. One measure of the change is the generation of electricity. Lenin had famously said that “Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country,” but it was not until the 1950s that electricity generation really took off, benefiting both consumers and industry (Figure 16.4).

Figure 16.4 Soviet electricity generation, 1921–1989 (milliard kWh). Based on Christian, Imperial and Soviet Russia, 437. Reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan.

However, policies intended to improve living standards committed the government not just to improvements but to sustained improvements, as expectations rose. Over the next two decades, maintaining that consumerist bargain would prove increasingly difficult as growth rates slowed, forcing the government to pay for improved living standards from existing resources rather than from gains in efficiency. Oil and natural gas or taxes on alcohol consumption helped pay for foreign grain that was used to feed livestock to maintain supplies of meat in the towns. Subsidies rose on food and consumer goods, on rents, electricity, and transportation, hiding real costs, distorting prices, and weighing down the budget. One measure of the extent of these subsidies was the rise in prices at collective farm markets, where peasants sold produce from their private plots at market prices.

In the long run, such methods were not sustainable. Between 1966 and 1970, per capita consumption of all goods and services rose at 5.1 percent per annum; by the early 1970s the rate had fallen to 2.9 percent, and by 1981 to 1.8 percent.13 By the early 1980s, even supplies of basic foodstuffs were unreliable, and rationing was introduced in some regions. Though the gap in living standards between the USA and the USSR had narrowed in the 1950s and 1960s, it began to widen again in the 1970s. In 1980, Soviet GDP per head was just under 50 percent that of the USA, only a slight improvement on the relative figure (40 percent) for 1938.14

While it kept prices low, the government could not supply enough high-quality goods. Consumers lived in a seller's market, characterized by chronic shortages, poor service, and lengthening queues, because the Soviet Union's 50,000 odd enterprises and 50,000 odd state farms and collective farms catered to planners, not to consumers. Where supplies were limited and unpredictable, consumers had to use informal methods to get goods, creating large semi-official quasi-markets or networks of barter. To buy goods such as cars, consumers exploited influential contacts, or paid bribes, or haggled with officials. All lived with the frustration and tedium of standing in endless queues. Indeed, queuing became a sort of informal tax on people's time. It could absorb hours each day, particularly for women, who did most of the shopping in a world where peasant ideas of gender roles still persisted. The stresses of living in a seller's market affected everyone, but none more so than single mothers. Though the Soviet system prided itself on the provision of childcare, the quality of care was poor.

In the 1970s, evidence began to accumulate of a growing health crisis. At first, industrialization and urbanization had raised levels of health care, reduced infant mortality, and increased life expectancy. Between 1950 and 1971, deaths during the first year of life had fallen from 80.7 for every thousand babies to 22.9. By 1987, they had risen again to 25.4 deaths per 1,000. While life expectancies were rising almost everywhere else in the world, life expectancy for Soviet males fell from 66.1 years to 62.3 years between 1960 and 1980, as a result of alcoholism, poor diets, and polluted urban environments.15 Health deteriorated because health services were underfunded, women were forced to use abortion as a form of contraception, pollution levels were high in the towns, and people drank more alcohol. Heavy drinking topped up the state budget, but also increased the number of industrial and traffic accidents and the level of domestic violence. The government made only tokenistic efforts to reduce alcoholism, because alcohol taxes generated such huge revenues. By 1984, alcoholic drinks accounted for about 12 percent of government revenue, because 90 percent of the cost of alcohol went into turnover taxes.16

Slowing growth threatened the social contract of the 1950s. But it also threatened the Soviet Union's other major goal: maintaining a defense establishment adequate for a modern global superpower. Waste and inefficiency meant that it cost more for the Soviet Union to maintain a modern defense establishment than for the USA, whose economy was about twice as large. Roughly speaking, this meant that the Soviet Union had to devote twice as large a share of output to defense as the USA, and that does not include the increasing costs of maintaining and policing the Soviet Union's eastern European empire. At huge cost, the Soviet Union did maintain a credible nuclear and conventional defense force in the 1960s and 1970s, and something like military parity with the USA. But by the 1980s, it was clearly falling behind. Soviet planners were slow to introduce computer technology, so that, while US weapons became smarter, the Soviet Union continued to rely on the number and explosive power of cruder weapons. These technological differences provide an apt symbol of the difference between a command economy that focused on mobilization and a market economy that focused more on innovation and the efficient use of resources.

As growth slowed, society changed, and so did popular attitudes. In 1928 about one fifth of the population lived in towns; in 1965 slightly over half; and by 1989 about two thirds of the population lived in towns. Between 1959 and 1980, the number of cities with more than 100,000 people doubled from 123 to 251.17 Educational standards also rose. As late as 1959, 91 percent of urban workers and 98 percent of rural workers had no secondary education; by 1984, just 19 percent of manual workers lacked secondary education.18 The peasant society of the 1920s was now a society of well-educated urbanites, with new expectations and a more critical attitude to politics and ideology.

As important as social changes was a growing awareness of change. Though the government jammed overseas broadcasts and censored printed information from the West, knowledge of conditions in the capitalist world seeped in through many channels, including western broadcasts, contacts with western visitors and students, and hurried official trips abroad. The sociologist Tatyana Zaslavskaia described the impact of her first trip abroad in 1957, to Sweden.

It made a very great impression indeed on me; before me was another, a different way of life, people with different values, needs, opinions, and different ways of organizing the economy and solving social problems. This experience not only broadened my mental outlook, it threw additional light on our own domestic problems. My own personal impressions shattered the idea I had been given that the life of working people in the West consisted mainly of suffering. We saw that, in fact, the countries of the West had in many instances overtaken us and we had lively discussions about ways of overcoming our own weaknesses.19

In the 1930s, a crude, Sunday School Marxism and the heroic slogans of Soviet propaganda could impress illiterate peasants disorientated by the upheavals of the first Five-Year Plans. They no longer impressed well-educated city dwellers in the 1970s, or students forced to take university courses in Diamat (or “dialectical materialism”). The social historian Boris Mironov describes how, as an exemplary undergraduate student at Leningrad University, he began to criticize Marxist dogma in three essays he wrote in 1961.

In the first, I demonstrated that under capitalism no impoverishment of workers had occurred …; in the second, I argued that capitalist profits were derived from the exploitation of natural resources and not that of workers; and in the third, I put forward the theses that in the USSR public property actually belonged not to the people, as socialism dictated, but to the nomenklatura and that Soviet workers were exploited as ruthlessly as anywhere.20

As in the nineteenth century, the most alienated were those on the fringes of the Soviet elite, with lots of education but few privileges.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Soviet intellectuals lived through a cultural thaw, while Khrushchev's secret speech (it was not secret for long) set a powerful precedent for criticism of the system. In 1962, Khrushchev allowed the journal Novyi Mir to publish Alexander Solzhenitsyn's novella about life in the labor camps, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. But Khrushchev's successors checked the thaw. In 1967, a military historian, A. M. Nekrich, who published a work criticizing Soviet lack of preparation for World War II, was dismissed from his position and attacked publicly for his criticisms of Stalin. The KGB began to clamp down on dissidents, who resorted to unofficial ways of publishing their writings. Some published abroad, while others borrowed the technology of chain letters, inviting readers to type out what they had read and pass it on in what came to be known as samizdat or “self-publication.”

In 1967, Yu. V. Andropov (1911–1984) became head of the KGB. Over the next 15 years he conducted a subtle and highly successful campaign against dissidents, using methods slightly less heavy-handed than Stalin's. He expelled influential writers such as Alexander Solzhenitsyn, but incarcerated other dissidents in camps or internal exile or in psychiatric hospitals. But as the KGB tried to drive dissident ideas underground, the same ideas began to spread within the Soviet ruling elite and even within the nomenklatura. By the 1980s, there was widespread and profound cynicism about Soviet achievements, goals, and methods of rule. Support for the system was being hollowed out from within. This is the main reason why the system collapsed so rapidly once the political elite itself gave up on it.

THE PROBLEM OF EFFICIENCY AND ECONOMIC GROWTH

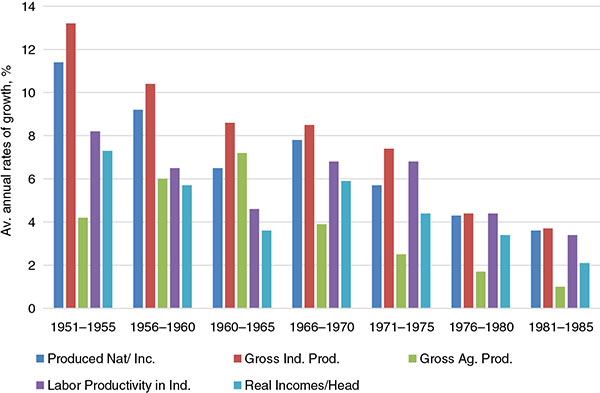

The system's primary failing was mobilizational. The elite began to lose faith in the system because it could no longer generate enough resources to satisfy consumers and maintain military parity with the USA. Soviet growth rates looked impressive in the 1950s and 1960s.21 Then growth slowed. Particularly worrying was the fear that official output figures flattered Soviet economic performance. Some calculations suggest that growth rates were actually falling by the 1980s. (See Table 16.1 and Figure 16.5.)

Table 16.1 The slowdown: Soviet economic growth, 1951–1985 (average annual rates of growth, official data, %)

| Produced national income | Gross industrial production | Gross agricultural production | Labor productivity in industry | Real incomes per head | |

| 1951–1955 | 11.4 | 13.2 | 4.2 | 8.2 | 7.3 |

| 1956–1960 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 5.7 |

| 1961–1965 | 6.5 | 8.6 | 7.2 | 4.6 | 3.6 |

| 1966–1970 | 7.8 | 8.5 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 5.9 |

| 1971–1975 | 5.7 | 7.4 | 2.5 | 6.8 | 4.4 |

| 1976–1980 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 1.7 | 4.4 | 3.4 |

| 1981–1985 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 2.1 |

Source: Table and graph based on White, Gorbachev in Power, 85; figures from Narodnoe khozyaistvo SSSR 1922–1972 gg. (Moscow, 1972), 56; and Narodnoe khozyaistvo SSSR za 70 let (Moscow, 1987), 58–59.

Figure 16.5 Average annual rates of growth, USSR, 1951–1985, based on Table 16.1.

What had gone wrong? At the deepest level, the system's problems arose from over-reliance on direct mobilization. The system built under Stalin was good at mobilizing resources, but not very good at using them economically so as to maximize the value they yielded. In a world where output was growing fast in the rest of the world, the Soviet Union was bound to run out of resources if it continued to use them so extravagantly. But that is what it did, turning, one by one, to a series of new resource bonanzas. Furs and grain had been major sources of resource wealth in Tsarist Russia. Stalin had tapped vast reserves of “spare” labor, but those reserves had now been used up, post-Stalin governments were unwilling to mobilize labor using extreme coercion, population growth was slowing in the Slavic heartland, and so was rural migration to the towns. What other forms of resource wealth were there?

In the post-war era, fossil fuels offered a new bonanza.22 In 1940, Azerbaijan still produced about 87 percent of Soviet oil, but in the 1950s the Soviet Union discovered vast new reserves of oil and natural gas in western Siberia. In the 1960s, new oil fields were found in western Kazakhstan and in Tiumen’ in western Siberia, and in 1968 oil overtook coal as the primary source of Soviet energy.23 By 1970, new fields were producing over 70 percent of Soviet oil. The Soviet Union started exporting oil again in the 1950s and by 1960 it was the world's second largest producer of oil after the USA. As in the 1920s, the “soft budget constraints” of the Soviet Union's non-capitalist economy allowed it to undercut capitalist producers; it sometimes sold oil at half the price of Middle East oil.24

The Soviet Union also began to produce natural gas on a large scale.25 Natural gas was discovered, first, as a by-product of the search for oil. It was used for street lighting in major cities of Tsarist Russia, but Soviet planners were slow to realize that it could produce energy more cheaply than coal or oil. In 1965, natural gas contributed just 2.4 percent of Soviet energy supplies, less than the contribution of wood and peat.26 But from the late 1950s, large gas fields were discovered in the Krasnodar region, Ukraine, and Central Asia, and above all in western Siberia. More than 230 new gas fields were discovered during the Seven-Year Plan (1959–1965). In 1965 the government established a separate Ministry of the Gas Industry of the USSR (which would eventually morph into today's Gazprom). By 1970 natural gas was supplying a fifth of Soviet energy requirements.27 From the mid-1970s massive gas fields were developed in the Tiumen’ region, which today accounts for 90 percent of natural gas production in the Russian Federation.28 The Soviet Union also built a large network of wide-diameter pipelines.

Fossil fuels, most from beyond the Soviet heartland, generated huge resource rents and plenty of foreign currency as international prices rose in the 1970s, after the 1973 oil crisis and the OPEC embargo on excess production. International prices for oil rose from below $20 a barrel to more than $40, and after the overthrow of the Shah of Iran in 1979, they would reach $70 a barrel, almost four times the price just 10 years earlier.29 In 1970, the Soviet Union had received $0.87 billion from oil exports; by 1980 it was receiving $12.97 billion, or 15 times as much.30 A recent calculation suggests that by 1980 the resource rents earned by the Russian Federation alone rose from almost nothing to about $250 billion a year for oil and almost $400 billion a year for gas.31

The bonanza from oil and gas hid the government's economic problems, while the “soft budget constraints” that allowed the Soviet government to sell energy abroad at fire-sale prices ensured that it would use these vast resources wastefully. Abundant gas and oil also tied the fate of the Soviet Union to global energy prices, and some began to talk of a Soviet “resource curse.”32 As the Netherlands found after the discovery of the Groningen gas field, a resource bonanza could have curious economic effects because, while resource prices are high, a country's real exchange rates may rise, encouraging imports and discouraging the manufacture and export of non-resource goods. This complex of issues came to be known as the “Dutch” disease. If resource rents were to start falling, would the Soviet Union still be able to maintain its consumerist bargain with the population, as well as its vast defense establishment?

For a time, the resource bonanza hid these problems. In 1987, Gorbachev argued that most apparent growth since the mid-1960s had come from two main sources: the sale of oil abroad and vodka at home.33

Clearly, the Soviet Union had to reduce its dependence on resources by improving efficiency and raising productivity. This was the fundamental challenge, and most Soviet economists understood the problem. Even in the Stalin era, some understood how dangerous it was to rely for too long on direct mobilization of resources. In the 1950s, after almost two decades of insisting that Soviet society had freed itself from the constraints of traditional economic laws, the government allowed economists to return to such problems. However, they did so within paradigms shaped by Marxism, which limited the solutions they could consider.

Most economists understood that raising efficiency meant finding ways of incorporating market forces within the command economy. Some looked to the NEP for a model of a society that combined planning and market forces.34 Unfortunately, the NEP period seemed to demonstrate the instability of any system that tried to combine planning and markets. While planning stifled entrepreneurial initiative, markets seemed to undermine planning. So how could market forces be incorporated within an economy profoundly biased towards direct mobilization?

One possibility was to set planning targets that rewarded productivity-raising innovations. But despite years of experimentation, it proved almost impossible to do this within the structures of the planned economy. It was not even clear how to measure productivity in a system whose prices were determined by planners rather than by supply and demand. Marx's “labor theory of value” also distorted prices by encouraging planners to overvalue labor, to undervalue resources, from water to oil and gas, and to ignore problems of scarcity. Planners understood that the statistical information they were using was artificial and distorted, and some preferred to use CIA estimates of Soviet productive capacity. Price distortions could have huge consequences, as in Central Asia's cotton economy, where water was treated as a free good, creating an ecological catastrophe as over-irrigation drained the region's major rivers.

Rewarding innovation was also tricky. Since the early 1930s, the main task of enterprises had been to get the job done, to fulfill the plan. And not to over fulfill the plan, because that would just ensure that next year the planners would raise targets. But whatever happened, no manager wanted to innovate at the risk of missing planned targets. After all, innovations were expensive and disruptive, and could take years of fixing and tweaking. In such an environment, managers feared innovating unless the government assumed all the risks, and that deprived managers of any incentive to innovate efficiently. Brezhnev once remarked that Soviet managers and planners shied away from innovations, “as the devil shies away from incense.”35

It was equally hard to know how to discipline inefficient enterprises, even if they could be identified. Some, such as power stations, were so vital that the government could not afford to let them close, however inefficiently they were managed. If the state did close an enterprise, it would then have to create a new enterprise to take its place, with no guarantees that the new enterprise would perform better. Disciplining workers was equally difficult where labor was in short supply. Most managers regularly hired more workers than they needed to make sure they could meet unexpected crises and deadlines.

Could tighter, better-informed planning solve the problem, perhaps with the aid of computers? Far too often, the central planners simply got their sums wrong, ordering the production of shoes of the wrong size or type, or designing clothes that no one wanted whatever the price. Part of the problem was that enterprises had to please planners, rather than the consumers who actually bought their products. Naturally, quality suffered. The Soviet Union produced more than twice as much footwear as the USA, but its quality was so poor that many didn't sell, and the Soviet Union had to import shoes; it produced more steel than the USA, but fewer useable finished products.36 Enterprises didn't care as long as they met their plan targets, and it was almost impossible to devise plans that measured quality rather than quantity. In any case, calculating the precise flows of resources needed to run an economy of over 200 million people, and more than 200,000 industrial enterprises, turned out to be a problem beyond even the theoretical capacity of computers. Markets really were better at providing economic information than planners.37 Besides, the government's attempts to limit the flow of potentially subversive information ensured that computerization would be a slow and painful process. Even photocopiers had to be registered with the police in case they were used to copy the wrong sort of information, such as the writings of dissident authors.

Soviet economists kept returning to the mechanisms that encouraged productivity in market economies. But introducing the market driver meant reducing rather than increasing the mobilizational power of the center, and creating legal and economic space for risk-taking and innovation by individual entrepreneurs. This is why most reform plans of the post-Stalin era depended on some form of decentralization. In 1957, Khrushchev devolved authority for many planning decisions to regional sovnarkhozy (“Regional Economic Councils”). The idea was that regional planners would use local resources more efficiently, but the real effect was to break inter-regional supply chains and encourage regional hoarding. The experiment was abandoned in 1965, after Khrushchev's removal.

Aleksei Kosygin presided over reforms introduced in 1963 that placed selected enterprises on a khozrashchet, or “economic calculation” basis. Such methods had been tried in the NEP period. They judged enterprises less by raw output targets than by profits, in other words, by the efficiency with which they met their targets. Managers were given greater control over contracts and supplies, which, in theory, allowed them to shop around for better deals. But where most enterprises lacked such flexibility, shopping around for cheaper supplies was extremely difficult, and promised few rewards. In 1969, wholesale markets accounted for only around 0.3 percent of national income.38

Events in eastern Europe in the late 1960s showed that decentralizing reforms could be politically dangerous. The reforms of the Czech “Prague Spring” in 1968 began with measures similar to those introduced by Kosygin. The logic of economic reform encouraged Alexander Dubcek (1921–1992), the First Secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, to allow the formation of independent trade unions and eventually of non-communist parties. In August 1968, after Dubcek began to talk of leaving the Warsaw Pact, Soviet leaders sent in 250,000 Warsaw Pact troops to prevent Czechoslovakia from drifting into the capitalist orbit.

Under an ageing leadership, scarred by war, time, and Stalinism, there was no longer much enthusiasm for tackling these thorny issues by the late 1970s. Living off the fat of a resource bonanza was so much easier. By 1980, the average age of Politburo members was 70, that of the Secretariat was 67, while that of the Council of Ministers was 65.39 Meanwhile, Brezhnev's policy of “stability of cadres” allowed a sometimes frustrated younger generation of regional bosses and industrial managers to entrench their power and authority at lower levels of government. This was particularly true in the republics, where a series of leaders, all from the titular nationalities of their republics, held power for much of the period after the fall of Khrushchev. In Azerbaijan, Heidar Aliev was head of the republican Party from 1969 to 1982; in Belorussia, Petr Masherov from 1965 to 1980; in Georgia, Vasili Mahavanadze and then Eduard Shevardnadze from 1953 to 1985; in Kazakhstan, Dinmukhamed Kunaev from 1960 to 1986 (with a brief spell out of office); in Kyrgyzstan, Turdakun Usubaliev from 1961 to 1985; in Tajikistan, Jabar Rasulov from 1961 to 1982; in Turkmenistan, Mukhamednazar Gapurov from 1969 to 1985; in Uzbekistan, Sharaf Rashidov from 1959 to 1983; in Ukraine, Petr Shelest and then Vladimir Shcherbitsky from 1963 to 1989.40 None of these leaders had much enthusiasm for decentralizing reforms that would threaten the networks of power and privileges they had built up while in office.

PERESTROIKA AND COLLAPSE: 1985–1991

By the mid-1980s, economic growth and globalization were eroding the economic and cultural barriers of the Cold War, while a booming global capitalism was raising the bar for economic, technological, and military success. Productivity rose around the world, and so did living standards for a growing global middle class. The planned economies of the socialist world struggled in a world where success meant not just effective mobilization, but also innovation and growth.

In the Soviet Union, generational turnover at the top released a torrent of reforms after 1985, and just six years later, in 1991, the system collapsed. The collapse was not inevitable, though without major reforms, continued decline was predictable. The system might have struggled on through decades of increasing senescence, like North Korea or Cuba, just as the Mongol Empire might have survived for a few more decades had Khan Mongke lived longer.41 But in both the major planned economies of the Soviet Union and China, new leaders decided that pre-emptive reforms were necessary to avoid collapse. The question was: how to reform the system? Leaders in these two former empires took very different approaches to the task, with very different outcomes.

1985–1990: LAUNCHING REFORM

As in 1260 and February 1917, transformation began at the top. In both China (after the death of Mao in 1976) and the Soviet Union (after the death of Konstantin Chernenko [1911–1985] in 1985), a new generation of officials and politicians came to power, with the energy and imagination needed to undertake fundamental reforms. All agreed that market mechanisms of some kind had to be incorporated within the planned economy. The tight grip of the center was stifling initiative, creativity, and innovation.

In the West, neoliberal economists saw the reforms of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher as examples of how to increase economic efficiency by reducing the role of the state and increasing the role of market forces. The key, according to the “Washington consensus,” was deregulation, reducing the grip of the state and unleashing the creativity of competitive markets. In the socialist world, they argued, governments should move fast to deregulate prices and privatize resources and businesses. Then they should step out of the way. Though such reforms might hurt consumers by removing subsidies on consumer goods, speed was necessary to circumvent opposition and unleash the full power of market forces.

But this was not the only possible model for reform. The East Asian tigers, such as South Korea and Singapore, had built vibrant market economies under strong states that actively managed economic development. This was also the path that China would take after Deng Xiaoping became paramount leader in 1978. Deng introduced cautious market reforms in particular regions, often with foreign help, advice, and finance, and the support of the Chinese diaspora.

In the Soviet Union, economic pressures mounted in the early 1980s. In the middle of a prolonged and costly war in Afghanistan launched in 1979, the price of oil and gas began to fall, slashing resource rents. Those generated just within the Russian Federation fell from over $250 billion a year for oil and $400 billion for gas in 1980 to less than $100 billion a year for oil and less than $200 billion for gas in 1990.42 At least one expert has argued that this change alone was

fatal for the Soviet economic and political system. The lack of alternative sources of revenues in the country led not only to the freezing of many investment projects and a drop in the population's living standards, but also to a complete destruction of the economic mechanism on which the Soviet system had rested over the previous two decades.43

Coincidentally, oil production in western Siberia and oil exports began to decline from the mid-1980s, because the most accessible oil fields were producing less, and the government had balked at the investment needed to find and exploit oil fields in more remote regions.44

These pressures help explain why, when the older generation of leaders left, between 1982 and 1985, reform came swiftly onto the agenda. Brezhnev died on November 10, 1982. He was succeeded as General Secretary by the former head of the KGB, Yuri Andropov. Despite his previous role, Andropov was widely regarded as an economic reformer. He had been impressed by the socialist market reforms he had seen as ambassador to Hungary before 1956. And as head of the KGB he understood better than his colleagues the cynicism and disillusionment of many Soviet citizens. He launched tentative reforms using both economic lures and political pressure. He attacked high-level corruption and tried to tighten work discipline. But he also tried to encourage the economic initiative of enterprise managers by increasing their control over budgets and bonuses.

However, similar reforms had not succeeded in the past. In any case, Andropov was unwell when he took office, and lacked the time and energy to introduce a sustained program of reforms. He vanished from public view in August 1983 and died on February 9, 1984.45 Though Andropov had hoped to be succeeded by his friend, the reformer Mikhail Gorbachev, his colleagues elected Konstantin Chernenko, the last leading member of the Brezhnev generation. Chernenko was already 72 and in poor health, so few were surprised when he, too, vanished from public view in December 1984. His death, on March 10, 1985, broke the log-jam. Gorbachev was elected as the new leader with the support of the long-term foreign minister, Andrei Gromyko.

Mikhail Gorbachev (1931–) represented a new generation of leaders, born in the Stalinist era but shaped by destalinization. Gorbachev claimed that many of his generation saw themselves as “children of the Twentieth Congress”; their “obligation” was to continue the reforms begun by Khrushchev.46 They had the commitment, the knowledge, the incentive, and now the power to launch serious reforms. For Soviet citizens, it was a relief to see a younger, more vigorous, and better-educated cohort of leaders. Wags asked, “What support does Gorbachev have in the Kremlin?” Their answer: “None – he walks unaided.”47

There was a rapid changing of the guard. Of 14 members of the Politburo in 1981, only 4 remained in 1986. Within a year of Gorbachev's accession, 70 percent of ministers were new. By 1989 all republican First Secretaries had been replaced, and most lower-level Party officials.48

Most of the new leaders understood the need for reform, though there was little agreement about details or strategies. Gorbachev gave his diagnosis in his 1987 book, Perestroika. Soviet economic growth had been slowing for at least 15 years and the Soviet Union was falling behind in efficiency, technology, and productivity. But over-abundant resources had allowed governments to postpone reform.

Our country's wealth in terms of natural and manpower resources has spoilt, one may even say corrupted us. That, in fact, is chiefly the reason why it was possible for our economy to develop extensively for decades. Accustomed to giving priority to quantitative growth in production, we tried to check the falling rates of growth, but did so mainly by continually increasing expenditures: we built up the fuel and energy industries and increased the use of natural resources in production.49

The challenge was to move from extensive growth based on mobilization of more resources to intensive growth based on more efficient use of resources. It was vital to make more effective use of the “human factor,” the creativity, initiative, and energy of the Soviet people, by reducing government supervision and increasing the rewards for innovative work. It was also vital to relax the government's grip on information so as to create a better informed populace. Abroad, he argued for a less confrontational foreign policy that would allow a reduction of the military budget. “Acceleration,” “new thinking” on foreign policy, and increased openness or glasnost’ became the watchwords of the new era of perestroika or “rebuilding.”

These reforms smacked of the Washington consensus, so it is no surprise that Soviet reforms would diverge sharply from the reforms that had begun in China. China's leaders resisted democratic political reforms, yet managed to integrate the market driver within a strong and apparently stable state structure, and generate remarkable rates of economic growth. Such a strategy worked in China partly because China still had large reserves of rural labor to drive rapid industrialization. Furthermore, capitalism had not been eradicated as completely as in the Soviet Union. In China, capitalism vanished for just a generation and memories of a market economy were still alive even in rural areas. In the early 1980s, when Chinese governments allowed individual households to farm separately, everyone remembered who had farmed which plots; many began to farm their former plots enthusiastically and sell their surplus produce.50 In contrast, three generations of Soviet citizens had lived without capitalism. That was long enough to efface all memory of the skills, the networks of credit and supply, and the habits of thought needed in a market economy. They knew nothing of buying and selling, of careful budgeting, or of entrepreneurial risk.51 When Gorbachev was in charge of Soviet agriculture, he told a Hungarian reformer that, “Unfortunately, in the course of the last fifty years the Russian peasant has had all the independence knocked out of him.”52

Yet Soviet leaders also proved less willing and able than their Chinese counterparts to learn from the capitalist world. In any case, the Russian capitalist diaspora, which might have helped with reform, was smaller and generally less entrepreneurial than the vast Chinese diaspora. Under Deng Xiaoping (1904–1997), the Chinese government sought out the expertise and advice of Chinese capitalists abroad, beginning with Hong Kong. Deng Xiaoping also dipped his toes more cautiously into market waters, trying out reforms in special regions rather than across the entire economy. His approach was experimental and pragmatic. As early as 1961, he had famously remarked that it didn't matter what color a cat was as long as it caught mice. In contrast, early Soviet reforms were based on the ideas of Soviet economic theorists with a limited understanding of competitive markets, and they were launched across the entire Soviet Union.

Finally, in the Soviet Union middle-level managers and officials had entrenched their power during the Brezhnev era, and managed to resist many initiatives from the center. In contrast, the Chinese government had retained immense authority over the regions, because the instability of the Cultural Revolution had prevented the consolidation of regional networks of officials and managers.

Like Andropov, Gorbachev's first reflex was to reach for the traditional levers of power. He tried to enforce work discipline and, with the support of Egor Ligachev, to reduce alcoholism. Like Tsar Nicholas II's disastrous experiment with prohibition at the beginning of World War I, the ill-prepared anti-alcohol reforms were a fiscal disaster.53 After several years of declining oil revenues, the sudden drop in revenues from vodka sales doubled the budgetary deficit from 3 percent of GDP to 6 percent in 1986. Anders Aslund argues that, “Perhaps more than any other single measure, the anti-alcohol campaign hastened the economic collapse of the Soviet Union.”54 The failure of this well-intentioned reform illustrates the government's unfamiliarity with capitalist accounting, and its continued reliance on “soft budget constraints.” Such commercial ignorance and fiscal indiscipline would eventually lead to hyperinflation and near bankruptcy.

More successful was Gorbachev's program of “new thinking” in foreign policy. Estimates of Soviet defense expenditure ranged from 17–25 percent of GDP in the mid-1980s. In an interview with Time Magazine in September 1985, Gorbachev noted, “We would prefer to use every ruble that today goes for defense to meet civilian, peaceful needs.”55 Early in 1986, he announced plans to abolish nuclear weapons. In November 1985, he held the first of several summits with President Reagan, and in 1989 the Soviet army withdrew from its disastrous attempt to prop up a pro-Soviet government in Afghanistan. So determined was Gorbachev to reduce defense expenditure that his government made no effort to protect its eastern European allies when their governments began to topple at the end of 1989.

Serious economic reform began in 1986. At the twenty-seventh Party Congress, Gorbachev described economic reform as “the key to all our problems, immediate and long-term, economic and social, political and ideological, domestic and foreign.”56 Like many Soviet economists, Gorbachev took the NEP era as the model for a socialist market economy. No one in the leadership had real memories of the era, unlike Deng Xiaoping, who had been a student in Moscow in 1926. So it was easy to forget how unstable it was, how government policy had lurched between qualified support for market forces and attempts to crush an emerging bourgeoisie of kulaks and Nepmen.

In November 1986, individuals and families were allowed to set up small businesses undertaking work such as taxi driving or car repairs. From January 1, 1987, for the first time since 1921, the government let some Soviet enterprises trade abroad independently rather than through the Ministry of Foreign Trade. By 1989, most Soviet enterprises could trade abroad on their own initiative. In May 1988, the government allowed the creation of cooperative enterprises, and within two years, cooperatives employed 2.4 percent of the workforce and accounted for 3 percent of Soviet GNP.57 A 1988 law allowed rural households to take out long leases on plots of land, and even to pass them on to their children. In principle, at least, this change allowed a slow breakup of collective farms and their transformation into small semi-independent farms. If the economic reforms as a whole were reminiscent of the NEP era, the first attempts at agrarian reform harked back to the Stolypin reforms under Nicholas II, though they were launched in a much less promising environment for individual farmers.

A June 1987 law on enterprises took effect early in 1988. Once more, it attempted to stimulate the creativity and initiative of Soviet enterprises and their managers. Enterprises still had to meet planned targets, but were given more leeway in deciding how to do so, and more control over prices and profit levels. Essentially, the reform reduced the number of plan indicators that Soviet managers had to meet, which increased the power and independence of enterprise managers and their control over their enterprises.

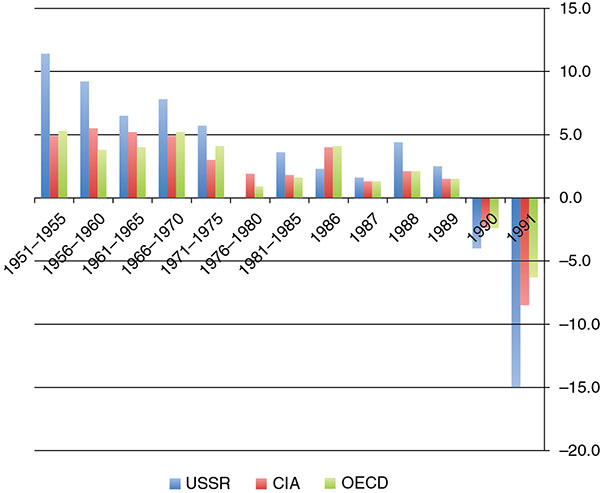

The economic reforms were intended to spawn a new entrepreneurial class, operating within and outside of the planning system. The hope was that this new class would compete with existing enterprises and raise average levels of efficiency and productivity. But that is not what happened. Though a new business class did appear, its members usually found it easiest to generate revenues by collaborating with officials or managers operating within the planned economy. Managers and independent entrepreneurs collaborated to tap a new revenue stream that used existing networks of influence and power to turn public assets into private wealth. In short, they continued to act like traditional mobilizers (“rent-seekers” in the economists’ jargon) rather than entrepreneurs. They siphoned public wealth into private pockets, from where it could be moved, if necessary, to foreign bank accounts. By doing so, they began a creeping privatization of Soviet assets that the government had never intended. Meanwhile, the planning system broke down before market forces were developed enough to replace it. Growth rates fell, and by 1990 total output began to decline (Table 16.2 and Figure 16.6).

Table 16.2 Soviet GDP: Various estimates of % rates of growth, 1951–1991

| Source | 1951–1955 | 1956–1960 | 1961–1965 | 1966–1970 | 1971–1975 | 1976–1980 | 1981–1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 |

| USSR | 11.4 | 9.2 | 6.5 | 7.8 | 5.7 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 4.4 | 2.5 | –4 | –15 |

| CIA | 4.9 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 3 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 4 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 1.5 | –2.4 | –8.5 |

| OECD | 5.3 | 3.8 | 4 | 5.2 | 4.1 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 4.1 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 1.5 | –2.4 | –6.3 |

Source: Data from White, Understanding Russian Politics, Table 4.1, 119.

Figure 16.6 Various estimates of Soviet economic growth rates (%), 1959–1991. Data from White, Understanding Russian Politics, Table 4.1, 119.

What went wrong? There is no easy diagnosis, though some of the crucial factors have already been described. Falling oil prices deprived the government of the hard currency it needed to pay for imports. By the late 1980s oil prices had fallen from a high of over US$70 per barrel to the pre-1973 level of $20, and they would fluctuate around $15–$30 a barrel until the end of the 1990s. Egor Gaidar, who managed market reforms in the Russian Federation in the early 1990s, described the fall in oil prices as “the final blow.”58

Another problem was that so few of the preconditions existed for a flourishing market economy. There was little understanding of how markets worked, and both officials and consumers treated entrepreneurs with suspicion. Soviet law offered little protection for private property or commercial assets, nor was there a body of commercial law, so it was hard to know what rights entrepreneurs had over assets or what commercial activities were legal or how courts would handle commercial conflicts. There was no commercial banking system to provide cheap loans. And the price system was chaotic; most prices were still set by government bureaucrats, while others (often for the same goods) were set by market forces. Many made huge profits by exploiting these anomalies rather than by producing new wealth.

In any case, the Soviet managerial class, the group with the most experience of managing the Soviet economy, understood mobilization but not markets. They were used to working in monopolistic environments. But the reforms gave them increased power over enterprises, which allowed them to generate pseudo-profits by exploiting the many contradictions between the planned economy and the emerging market economy. Arbitrage was much more promising than innovation. The result was a growth in rent-seeking rather than in productive entrepreneurial activity. The notion of rent-seeking entered modern economic discussion through the work of Anne Krueger. A simple definition is “a search for financial benefits from state help or state protection against competition rather than from improving efficiency.” And, as that definition suggests, rent-seeking is a modern equivalent of the tribute-taking typical of traditional mobilizational systems, including that of Russia, with the (important) difference that it takes place within a modern, capitalist economy.59

The reforms failed to create an attractive environment for genuine entrepreneurial activity, but they also made it difficult to keep producing and trading in the old ways. As managers sought new supplies and markets, existing supply chains snapped, and enterprises had to seek new ways of generating revenues. Raising prices was one possibility, but managers learned quickly that in a market environment that reduced demand. Where enterprises lacked cash, they bartered with other enterprises, using the professional fixers or tolkachi who had flourished by helping enterprises get around the anomalies of the command economy. I personally heard in 1990 of a company in Minsk whose repair section offered its services to other enterprises in return for subsidized consumer goods such as vodka and sausages. These were distributed to workers in lieu of wages, and workers used the same goods to engage in private barter.

The widening gap between subsidized state prices and free market prices offered spectacular opportunities for arbitrage. Such revenues can rightly be described as “rents” because they did not derive from competitive market activity and did not raise productivity or increase efficiency, but derived from state protection or other non-market advantages. “The best way to become truly wealthy in 1990 was to purchase oil from a state enterprise at the official price of $1 a ton and sell it abroad for $100 a ton and finance the transaction with cheap state credits.”60 Enterprises soon realized that they could purchase goods at subsidized official prices and resell them at free market prices through tame cooperatives. For example, grain could be imported at subsidized prices and resold at much higher market prices through cooperatives. Finally, cheap state credits allowed the new and largely unregulated cooperative banks to make vast profits by reloaning cheap government money on the private market and at commercial rates of interest.61 As such practices spread, a river of wealth transported Soviet assets into private bank accounts, many of them abroad.62 Entrepreneurs found that it paid to work with officials who controlled local resources and could issue (or refuse to issue) licenses to trade commercially. Such relations generated corruption on a massive scale.

Genuine entrepreneurial activity was particularly difficult in rural areas. Collective farms discouraged individuals from taking up individual leases, or offered them unsuitable land. Local suppliers of seed, fertilizer, and farm equipment usually had close ties with collective farm chairmen, and little incentive to support independent farmers trying to break through the many administrative and legal barriers they faced. And the government did not always help. In 1990, Egor Ligachev, the Politburo member in charge of agriculture, said in an interview that he would allow decollectivization “over his dead body.”63 And indeed, collectivization was not abolished. Though collective farmers were allowed to leave and set up independent farms, few choose to do so, and many collective farms survived perestroika.

Few pitied struggling entrepreneurs, even in the cities. Used to a price stability that depended on government subsidies, consumers resented the high market prices charged by cooperative restaurants or hairdressers or independent farmers, even if their products and services were of better quality. Government officials found that their own authority could generate incomes by forcing entrepreneurs to pay for administrative services or permits or inspections. Local officials imposed arbitrary taxes and rents on cooperatives, or insisted on onerous safety inspections unless they received bribes. Transporting goods meant running the gauntlet of GAI, the traffic police or “state traffic inspectorate,” which was notorious for fining drivers for imagined violations.64 The absence of a clear corpus of commercial and property law ensured that most entrepreneurial activities were of uncertain legality, so most businesses had to pay bribes or protection money to officials or racketeers.

As anomalies multiplied, production began to fall and many began to fear the system was breaking down. A 1987 article in Novyi Mir titled “You cannot be a little pregnant” argued that there was no half-way house between capitalism and a command economy.65 In 1987 Vasilii Selyunin and Gregory Khanin published an article in Novyi Mir called “Tricky Numbers,” arguing that Soviet statistics had greatly exaggerated Soviet economic achievements, and that real growth had been declining since 1960.66 Both friends and foes of reform began to understand that reform might end in a collapse of the entire system.67

Resistance to economic reform eventually pushed reformers towards political reform, in the hope that popular support for change would help them outflank resistance from their own officials. This was a dangerous gamble, because it assumed broad popular support for economic reforms. But many ordinary citizens were learning that reform might reduce job security and raise prices. After all, most Soviet citizens depended on the Soviet welfare net, with its pensions and its subsidized prices for housing, health, and basic consumer goods. Rising government subsidies had insulated them from the system's economic problems.

In Perestroika, Gorbachev described the gamble on political reform with his customary over-confidence.

The weaknesses and inconsistencies of all the known “revolutions from above” are explained precisely by the lack of … support from below, the absence of concord and concerted action with the masses. … It is a distinctive feature and strength of perestroika that it is simultaneously a revolution “from above” and “from below.”68

In retrospect, it seems clear that Gorbachev had little understanding of the implications of political liberalization when he promised further demokratizatsiia at a Party conference in June 1988.69 In practice, “democratization” meant surrendering the center's power over the reform process. Deng Xiaoping's son is supposed to have commented to a friend, “My father thinks Gorbachev is an idiot [for reforming the political system before the economic system] … [H]e won't have the power to fix the economic problems and the people will remove him.”70

Political reform began with increasing “openness” or glasnost’. Gorbachev understood glasnost’ as a willingness to make more information available to the population. The Chernobyl disaster showed both the need for and the limits of glasnost’. On April 26, 1986, a nuclear reactor blew up at Chernobyl, 100 kilometers north of Kiev, during a routine maintenance check. It released more radioactivity than the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The government said nothing for two critical days, and even refused to cancel a May Day parade in Kiev, despite winds from the north that exposed everyone present to high radiation levels. Then, in a sharp reversal, it published remarkably frank accounts of what had happened. The awkward combination of secrecy and candor provoked distrust and anger.

The frankness of glasnost’ proved as ideologically corrosive as the ideas in Khrushchev's secret speech. As censorship eased in 1987, the media carried increasingly open discussions of the crimes and victims of the Stalin era, and shockingly detailed critiques of the Soviet system. Banned novels were published; discussions about drug use and prostitution appeared in the press for the first time; and former enemies of the people such as Bukharin and Trotsky were rehabilitated. In 1987, Gorbachev announced that there must be no “blank spots” in Soviet history, and described the “crimes” of the purge era as “wanton repressive measures.”71 By 1990, the Soviet press was remarkably free, and foreign observers noted that the traditional Soviet fear of critical talk seemed to have disappeared, even in conversations with foreigners.

In January 1987, Gorbachev declared that, “A house can be put in order only by a person who feels that he owns this house.”72 In June 1988, the nineteenth Party conference announced the establishment of a new parliamentary body, the “Congress of People's Deputies,” one third of whose members would be chosen by popular election. The Congress, in turn, would elect a new two-house Supreme Soviet from among its members. These were radical changes in a system where, for over 50 years, formal elections had masked a form of co-option through the nomenklatura. Genuine elections, with multiple candidates, threatened the security of elites, and the governing role of the Communist Party, and conservatives began to fear for the entire Soviet experiment. In March 1988, a Leningrad teacher, Nina Andreeva, published a widely read critique of the reforms, with the covert help of conservatives in the Party Central Committee.73

The Congress of People's Deputies met in May 1989, and, though most of its members were Party members, many were not. Millions of Soviet viewers watched its robust debates with astonished fascination.

1990–1991: THE SYSTEM UNRAVELS

In 1990, the government began to lose control of the reform process. Suddenly, “informal” groups that existed outside the formal governmental structures began to shape Soviet politics. Organizations such as “Memorial,” whose goal was to remember the victims of Stalinism, had emerged as early as 1988. They gained the support of influential dissidents such as the physicist Andrei Sakharov, whom Gorbachev had released from internal exile in 1986. In March 1990, it was agreed to remove article 6 of the 1977 Soviet Constitution, which had guaranteed the political hegemony of the Communist Party. This formally ended the monopoly on power that the Party had enjoyed since 1918.

Economic reform, glasnost’, and democratization empowered regions and constituencies that had been politically invisible for most of the Soviet era, and ancient fault lines reappeared. These included regional, ethnic, and national divisions. The revival of nationalism came as a shock to politicians such as Gorbachev, who believed the Soviet Union had solved the “national problem.” But they should not have been surprised, as Soviet leaders from the time of Lenin and Stalin had built the idea of nationhood into the structures of the Soviet Union. In the Brezhnev era, the idea of “ethnogenesis” flourished within official ideology, along with increasingly essentialist notions of nationhood, while republican politics was increasingly dominated by local elites, national histories were increasingly taught in schools, and national intelligentsias had emerged with a strong commitment to national cultural traditions.74