[18]

1991–2000: BUILDING NEW STATES: GENERAL TRENDS AND THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION

“[F]rom the very beginning, Russia was created as a supercentralized state. That's practically laid down in its genetic code, its traditions, and the mentality of its people.”1

Vladimir Putin

“Central Asia, the Caucasus, and even Russia have not in fact been struggling toward democracy. They are not temporarily trapped between communist dictatorship and liberal democracy. Rather, like many failed (or half-heartedly attempted) African transitions of the 1950s and 1960s, and again in the 1990s, these regimes have comfortably settled into new forms of authoritarianism that might continue for decades.”2

INTRODUCTION: AFTER THE BREAKUP: THE WORLD AND INNER EURASIA

The breakup of the Mongol Empire in 1260 snapped threads that had woven Inner Eurasia into a single mobilizational system with many links to Outer Eurasia. When the Mongol Empire collapsed, Eurasia as a whole became less connected. Seven hundred years later, the breakup of the Soviet Empire had the opposite effect. It ended the divisions of the Cold War and allowed the creation of new commercial, intellectual, and personal networks within a capitalist system that now included most of the world. The mechanisms of breakdown were also different. The Mongol Empire was seriously over-extended by 1260, which is why the death of a leader was enough to break it apart. Modern technologies of communication and transportation made distance more manageable in 1991, which explains why the Russian Republic, the largest surviving ulus after 1991, reached from eastern Siberia to the Baltic and the Black Sea.

The Soviet collapse can also be seen as a continuation of the process of decolonization that began after World War II. Like Europe's former colonies, post-Soviet states had to build new forms of legitimacy, new power structures, and new economies within a capitalist system in which they were latecomers, and within borders that were often arbitrary and made little geographical, ethnic, political, or economic sense.

This chapter focuses on the 10 years after the breakup of the Soviet Union, though occasionally it looks towards the first decade of the twenty-first century. It will describe some general trends, and then focus on the Russian Federation, the largest and most influential of the new post-Soviet states. Chapter 19 will survey more briefly the histories of new states in other parts of Inner Eurasia.

The Mongol Empire split into four new uluses, two of them within Inner Eurasia. Though all inherited Mongol traditions of governance, they would have quite distinctive histories depending on their geography, resources, and neighbors, and on the quality of their leadership. The Soviet Empire split into almost 30 distinct republics, 10 of which fall clearly within Inner Eurasia. All post-Soviet states inherited similar traditions of governance from the Soviet era, but they, too, would evolve along very diverse pathways.

I will refer to the 10 unambiguously Inner Eurasian post-Soviet republics using the awkward but precise acronym PSIERs, or Post-Soviet Inner Eurasian Republics. I include within this category the Russian Federation, Belarus, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Mongolia, and Azerbaijan. I exclude Moldova and the Caucasus republics (apart from Azerbaijan), as well as the post-Soviet polities of the Baltic and eastern Europe, on the grounds that these were not unambiguously part of Inner Eurasia. Though part of the Soviet Empire, the republics of the Caucasus had histories shaped by their quite distinctive geography, while Moldova and the Baltic republics had long been oriented to the West rather than towards Inner Eurasia. Ukraine (whose name means “Borderland”) is an interesting in-between case because, like the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania, it straddled the imaginary but important border we have drawn between Inner and Outer Eurasia. Ukraine's in-betweenness would have a profound impact on its post-Soviet history.

The idea of a distinct group of Post-Soviet Inner Eurasian Republics is helpful because there were some striking differences between the histories of the PSIERs and other post-Soviet states. These differences provide one more justification for the central argument of this book: that the history of Inner Eurasia really does have a certain coherence.

Of all the PSIERs, by far the largest, wealthiest, most powerful, and most influential was the Russian Federation, which included about 75 percent of the territory of the former Soviet Union. Russia survived now as a cut-down version of the Soviet Empire. So large was the Russian Federation that it continued, though with diminished force, to play the role of Inner Eurasia's heartland.

At the time of writing, 26 years after the collapse, all 10 PSIERs still exist, though Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine have survived serious internal conflicts, and there have been dangerous border conflicts, the latest being between Ukraine and the Russian Federation. All 10 PSIERs belong to the United Nations. All the PSIERs now have market or semi-market economies, and are integrated to some degree within world markets. And all have retained many of the forms of democratic government. But after early experiments with market reforms and more democratic styles of rule, most swung back towards more centralized styles of government and economic management. None have retained the Soviet Union's Marxist ideology despite widespread nostalgia for the Soviet era.

THE CHALLENGE

All post-Soviet leaders understood that the Soviet strategy of direct mobilization would no longer work in a world where growth trumped raw mobilization. They understood that their mobilizational strategies would have to incorporate market forces to some degree. Many post-Soviet countries in eastern and central Europe and the Baltic republics welcomed the challenge of economic reform with optimism and enthusiasm. But in Inner Eurasia, most leaders approached the task more cautiously and with much less enthusiasm. They knew that as they tried to build new systems with new forms of legitimacy, they would have to maneuver carefully to find the right balance between market forces and long-established traditions of direct mobilization and centralized governance.

All post-Soviet republics would end up somewhere on a spectrum between two main models of reform, which I will describe as the “neoliberal” and “Chinese” models of reform.

The neoliberal reform model was associated with the “Washington consensus,” a series of economic strategies applied to Latin American countries by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In the 1970s and 1980s it shaped the economic reforms of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.3 Advocates of this model insisted that excessive government interference in economic matters stifled market forces and slowed growth. To unleash the full creative potential of competitive markets, governments needed to limit their economic role. Applied to the former Soviet Empire, this model suggested the urgency of privatization, price liberalization, and a reduction in the economic role and power of the state. Key steps towards reform would include: the privatization of state-owned assets, deregulation of prices, the removal of most state subsidies, and the liberalization of internal and external trade. And change had to be fast to lock reforms in place. It was clear that such reforms would cause widespread suffering at first, but supporters of the Washington consensus model insisted that reforms would quickly unleash the market driver of growth, generating wealth that would trickle down to the population at large. Most neoliberal economists insisted that these were universal principles, so there was little need to modify reform programs to account for the particular historical, institutional, and cultural traditions of different countries. Twenty-six years after the reforms began, it is easier to see the limits of such a program. But in the early 1990s, for politicians seeking a rapid transition to a prosperous market economy (a transition to “normality,” as many put it), such programs offered the only clear way forward.

In contrast to the Washington consensus, the Chinese reform model (sometimes described as the “Chinese consensus”) preserved a large, even dominant, role for the state in economic management. To some degree, this model reflects the policies of all the East Asian “tiger” economies – South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, as well as China itself. In these countries, governments played a dominant role in directing and planning the economy and society, protected infant industries with tariffs, and invested generously in infrastructure, education, and social welfare. The Chinese model took the market driver very seriously, but insisted that political stability, careful planning, and the preservation of traditional social safety nets were equally important. And instead of “big bang” reforms, it introduced reforms more slowly and cautiously. The Chinese model was generally implemented more pragmatically, and was less driven by formal economic theory, so it adapted naturally to local historical and cultural traditions, and local traditions of governance. Many western economists treated the Chinese model with disdain, arguing that it was historically outdated, economically illiterate, and morally unacceptable. But early in the twenty-first century its strengths are easier to see. China's rapid economic development since the 1980s has demonstrated the potential of such an approach to economic reform, though critics have argued that it pays little or no heed to democratization and human rights, and will eventually stifle growth.

SOME GENERAL TRENDS

All the states created after the collapse of the Soviet Union had to find some balance between these approaches. Leaders in much of eastern Europe, and also in the Russian Federation, lurched violently towards market reforms, before making the many course corrections needed to balance market forces against local traditions and realities. Most of the PSIERs adopted a more cautious approach, closer to the Chinese model, and preserved many of the centralized political and economic structures of the Soviet era.

One crucial factor shaping the reform process was the extent of elite continuity. In 1991, as in 1260, elite continuity ensured that earlier habits of rule survived into the new era. In eastern Europe, there was considerable elite turnover. In the PSIERs, though, new leaders had mostly been formed within the Soviet nomenklatura, or at its margins. In the Russian Federation, an interview-based study of 1,800 individuals found that 78 percent of those in elite positions in 1993 had been members of the Communist Party in 1988, and at least 25 percent were children of the nomenklatura, while over 60 percent of members of the Soviet nomenklatura still held positions comparable to those they held in the late Soviet period.4 And they brought their Soviet-era attitudes with them. Egor Ligachev, one of the more conservative members of Gorbachev's Politburo, remained a communist after the collapse of the Soviet Union, helped found a revived Communist Party in 1993 after the 1991 ban on the Party was deemed unconstitutional, and was elected three times to the post-Soviet parliament as a communist, until losing his seat in 2003. As the oldest member of the Duma he was, briefly, the “father of the house.”

As David Remnick puts it, in Russia the average former apparatchik “hardly left his chair.”5 Gordon Hahn writes:

Russia's revolution from above involved the mass co-optation and incorporation of the former Soviet party-state's institutions and apparatchiks into the new regime. These institutions and bureaucrats constrained the consolidation of democracy and the market by bringing their authoritarian political culture and statist economic culture into the new regime and state, producing to date an illiberal executive-dominated and kleptocratic and oligarchical political economy.6

There was considerable elite continuity in most of the PSIERs. In 1997, seven heads of post-Soviet states had been First Secretaries of republican branches of the Communist Party, while for several years, meetings of heads of CIS member states looked remarkably like Politburo meetings of the late Soviet period.7 In Kazakhstan, a 1995–1996 interview study concluded that almost 70 percent of the elite had held executive or Party positions in the late Soviet era. In the Kazakh regions, too, there was significant continuity. One regional governor (or akim) commented in an interview that, “My experience as head of this oblast in the eighties has served me very very well in my present job. I rely still almost exclusively on the contacts I had in that period.”8 In Ukraine, Leonid Kravchuk, a former ideology secretary in the Ukrainian Party, emerged as leader after re-badging himself as a Ukrainian nationalist. In Belarus, former communist leaders survived until the 1994 elections, after which Aliaksandr Lukashenka, though not a high-ranking member of the Soviet nomenklatura, built a centralized system remarkably like that of the Soviet era, staffed largely by former members of the nomenklatura. In almost all of the Central Asian republics except for Kyrgyzstan, the new elites were dominated by former communist leaders, many with strong personal followings dating from the Soviet era, and anchored within regional clan networks. In none of the Central Asian republics were Soviet-era leaders challenged by strong pro-democracy movements.9

A high level of elite continuity was inevitable in the PSIERs because, in contrast to much of post-Soviet eastern Europe, there had not emerged coherent and powerful alternative elites. In Ukraine, as one contemporary put it:

power [had to] be given to someone. It is completely natural that it should fall into the hands of the nomenklatura. We simply did not … have any other social and political milieu which is sufficiently advanced in both quantity and quality, and therefore capable of building a state.10

Continuity in the political culture of PSIER elites was matched by continuity in popular attitudes. This was very different from the Baltic republics and eastern Europe, where Soviet rule had been imposed on societies with distinctive political and historical traditions. In most of the PSIERs, many, even within the liberal intelligentsia, preserved a Hobbesian respect for strong state structures. In March 1991, Gorbachev held a Soviet-wide referendum on the future of the Soviet Union.11 All republics of the Union took part, 80 percent of the population voted, and 76.4 percent voted to preserve the Union. Support was strongest in rural areas and Central Asia, and weaker in the large cities. Nine months after Gorbachev's poll, the Union had run aground, and moods changed, but a widespread nostalgia for the strong government of the Soviet era persisted, nevertheless. In Russia, though the Communist Party was banned in August 1991, former communists were not excluded from politics, and after the ban on the Party was declared unconstitutional in 1993, the revived KPRF or Communist Party of the Russian Federation performed well in elections. When polled in 1995, most Russians agreed that things would have been “better if everything had stayed as it was in 1985.”12 The stability and security of the “era of stagnation” looked increasingly attractive in the rear-view mirror of societies in economic free-fall.

Continuity in elite membership and popular political attitudes limited the break with past political traditions and methods in most of the PSIERs. As the formal structures of the old order crumbled, many of its informal structures, habits of mind, networks, and methods of administration and rule survived. Hardly any leaders of the PSIERs were committed democrats or free marketeers, and many came from the generation of nomenklatura politicians that had consolidated their power under Brezhnev, and lacked enthusiasm for perestroika. As formal structures broke down, such informal attitudes acquired great significance.13 The cultural momentum of old traditions of mobilization and elite cohesion helps explain why all the PSIERs would return within a few years to relatively centralized strategies of political and economic management.

The importance of elite continuity is shown by the example of the one PSIER in which there was considerable elite turnover. This was Mongolia, and Mongolia's fate in the 1990s was quite distinctive. By the end of the 1990s Mongolia had a highly marketized economy, and was generally classified as democratic and “free.” It was also much more open to international influences than any of the other PSIERs. True, Mongolia had also been less integrated into the Soviet economy than the other PSIERs, but all the same, its very different trajectory shows, as does the history of other countries, such as South Korea, that there was nothing impossible about the idea of a rapid transition from an authoritarian and largely planned economy to a market economy with relatively democratic political structures.

In most of the other PSIERs, elite continuity ensured the survival of traditional attitudes to revenue raising and mobilization, as well as to governance. In the 1990s, much revenue generation looked more like tribute-taking – like the Muscovite practices of kormlenie (“feeding”) or iasak – rather than the generation of capitalist profits. Modern economics defines such methods as “rent-seeking.” There are highly technical definitions of rent-seeking, but, as in Chapter 16, we can define it simply as “a search for financial benefits from state help or state protection against competition rather than from improving efficiency.”14 While regarded as a legitimate activity in traditional mobilizational systems (it is essentially the same as tribute-taking), within capitalist societies rent-seeking looks archaic, inefficient, exploitative, and illegitimate. Nevertheless, many post-Soviet officials and entrepreneurs persisted with such methods because they understood them. In November 1994, just as he turned away from radical market reforms, Aliaksandr Lukashenka, the newly elected President of Belarus, asked on live TV, “Do you know what a market economy is, can you work in market conditions?” When his audience answered, “No,” he continued, “And do you know what a planned economy is?” When his audience answered, “Yes,” he remarked, “Right, we will build what we know.”15

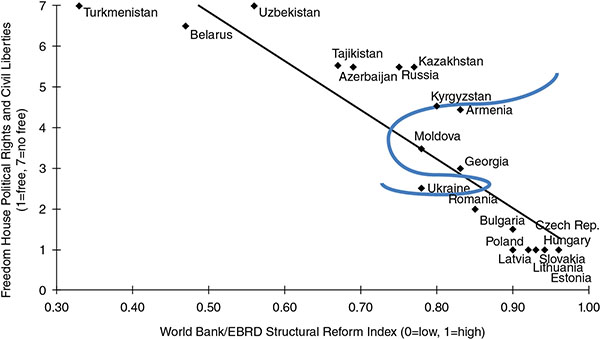

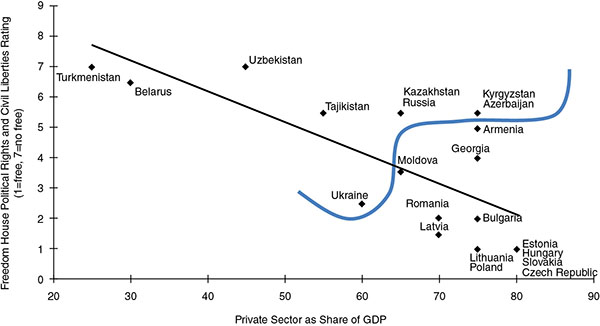

The contrast in methods of governance between the PSIERs and other post-Soviet polities is apparent from Figure 18.1, which is based on crude measures of democratization and marketization in 2005.16 According to these measures, the least democratic countries in 2005 (those above 4 on the “y” axis) were all PSIERs, with the exception of Armenia, which had also been part of the Soviet Union. The one PSIER with a better rating for democratic governance was Ukraine, whose western provinces had never belonged to Inner Eurasia, and whose democracy remained fragile and contested. The PSIERs were also laggards in market reforms, according to the World Bank's index of structural economic reform. Figure 18.2 shows that, with the exception of Kyrgyzstan and Azerbaijan, the PSIERs were also slower to privatize state assets.

Figure 18.1 Democracy and market reform in the PSIERs: the curved line separates PSIERs from other post-Soviet states. Based on Aslund, How Capitalism was Built, 246. Reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Figure 18.2 Democracy and privatization in the PSIERs: the curved line separates PSIERs from other post-Soviet states. Based on Aslund, How Capitalism was Built, 192. Reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press.

The twin challenges of political and economic reform were closely linked, but it may help to consider them separately because this can help explain why, in most of the PSIERs, the task of state building trumped the task of building modern market economies.

POLITICAL CHALLENGES

The collapse of Soviet-era borders, ideologies, and structures of legitimation forced a new generation of leaders to look for new forms of legitimacy and elite cohesion. None sought legitimation through Marxist ideology, even though most were former communists. However, the democratic rhetoric of the perestroika era, and the need to seek broad popular support after the collapse of older political structures, forced new leaders, whatever their own preferences, to seek legitimacy in three main ways: as democrats, as pro-marketeers, and as nationalists. Few had deep commitments to these goals so they moved towards them cautiously and sometimes grudgingly. Most would build “managed democracies,” with formally democratic structures controlled through electoral manipulation and government-managed mass media. They would also make grudging concessions to market forces. But the most congenial way of building support and legitimacy was through new forms of nationalism. Yet even this could be a tricky maneuver, given the artificial borders and the complex ethnic mixture of many PSIERs. Building new forms of elite cohesion was also a complex and messy process. In the new era, it depended on permissive attitudes to profit-making and rent-taking, and the preservation of traditional political networks and ties, many of them built in the Soviet era.

In all the PSIERs, political legitimacy meant building modern nation-states. But, with the exception of Mongolia, few of the Soviet-era republican borders coincided neatly with ethnic borders. Nevertheless, all the new leaders understood that they would have to live with Soviet-era borders because trying to renegotiate them could lead quickly to dangerous military conflicts. If they needed any reminder of these, it was provided by the bloody five-year civil war in Yugoslavia after 1991. That showed what could have happened on a much larger scale in the former USSR, with nuclear weapons thrown in for good measure. There were border wars in Moldova, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, and in Chechnya and Tajikistan. But in the 1990s there were no wars over the large Russian diasporas within the borders of Ukraine or the Baltic republics or Kazakhstan. Elite continuity played a role in this relatively peaceful transition because, despite the many centrifugal forces in play, most leaders of the PSIERs shared a common political culture and felt themselves to be more or less on the same team.

The primary task of all the new leaders, one faced by many former colonies in the twentieth century, was to build new power structures and new forms of legitimacy within borders that sometimes made little sense. Outside the Russian Federation and Mongolia, both of which inherited powerful national traditions, these tasks were so complex that they trumped the two other challenges of democratization and market reform.

With so many centrifugal forces at work, the first task was to prevent unraveling below the republican level. The breakdown of Soviet mechanisms of control, including the Communist Party itself, weakened links between the center and the regions. This was particularly dangerous where there were significant ethnic differences. At the edges of Inner Eurasia, in Moldova, Georgia, and Tajikistan, internal revolts were driven largely by ethnic and cultural tensions between new republican rulers and groups that did not fit easily into emerging national templates. The rulers of Ukraine and Kazakhstan, the largest of the new republics outside the Russian Federation, had to tread carefully to avoid igniting irredentist movements among their large Russian populations. All new leaders had to try to build a new vertikal’ of power that could bind regions to centers.

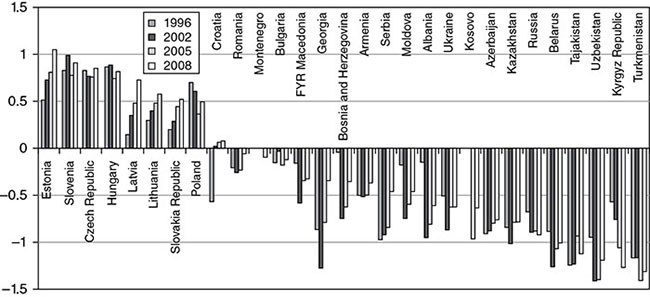

Both ethnic and political tensions had to be managed within the formally democratic parliamentary structures inherited from the Soviet era. But Soviet traditions, with their carefully managed parliaments, elections, judicial systems, and media, also showed how to use democratic structures as a form of legitimation, without letting them constrain central power. Figure 18.3 uses 2008 World Bank data to assess confidence in the rule of law in 29 post-Soviet republics. It uses expert evaluations of property rights, contract enforcement, confidence in the police and courts, and the pervasiveness of crime and violence. The PSIERs occupy 9 of the last 10 places, in a striking demonstration of the extent to which their leaders managed to remain above the law.

Figure 18.3 The rule of law in post-Soviet countries: World Bank data on confidence in the rule of law, based on expert assessments, and focusing mainly on property rights, contract enforcement, the police and courts, and the pervasiveness of crime and violence. Based on Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, 136. With permission of John Wiley & Sons.

ECONOMIC CHALLENGES

In most of the PSIERs except Russia, where there already existed a strong national tradition, and economic reforms had been debated at great length in the era of perestroika, the challenge of state building overshadowed the task of economic reform. Instead of systematic economic reform we see in most of the PSIERs grudging and ad hoc reactions to a new, capitalist environment in which market forces could no longer be ignored. Reforms in the Russian Federation, the demands of international agencies such as the IMF, and the pressures of international markets all required adaptation to market forces. The new republics also had to deal with the severe economic consequences of the breakup of the Soviet Union, which cut long-established supply chains.

Four general economic trends are worth highlighting: (1) changes in total output; (2) the role of resource exports; (3) changes in levels of marketization; and (4) increasing inequality.

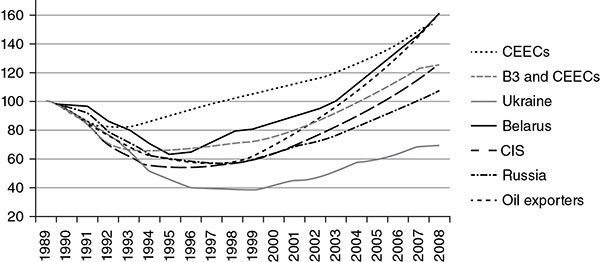

Estimates of economic output per capita in all post-Soviet states show a period of sharp economic decline followed by a period of recovery in the late 1990s. As Figure 18.4 shows, the fall was generally steeper in the PSIERs than in the Baltic republics and central and eastern Europe, and the upturn came later in the 1990s. However, in the first decade of the twentieth century, economic growth in some of the PSIERs, particularly those with large resource sectors, matched, and sometimes exceeded, output growth in the other post-Soviet republics.

Figure 18.4 GDP as % of 1989 level in post-Soviet countries. CEEC = Central–Eastern European Countries; SEEC = South-Eastern European Countries; B3 = Baltic republics; CIS = Commonwealth of Independent States (most former Soviet republics, excluding Baltic republics). Based on Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, 50. With permission of John Wiley & Sons.

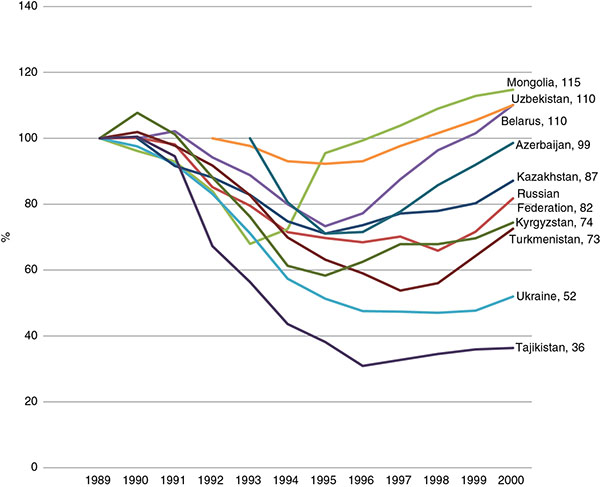

Figure 18.5, which is based on data from the World Bank (shown in Table 18.1) gives changing gross national income (GNI) per capita for the PSIERs between 1989 and 2000. Though such statistics provide an extremely crude sketch of complex changes, they do have important stories to tell. First, the decline was universal in the first half of the 1990s. In all post-Soviet republics, the sharp decline was caused by the breakdown of Soviet-era planning mechanisms before the emergence of robust market economies. In the PSIERs, per capita output fell to between 55 percent and 80 percent of the 1989 level. (Data for Uzbekistan flatter its performance because the base year is 1992, when output had already fallen.) In Ukraine and Tajikistan, output fell well below 50 percent. Output was generally lowest between 1994 and 1997, after which it began to rise, but only in Mongolia, Uzbekistan, and Belarus did output per capita exceed the 1989 level by 2000. Mongolia is exceptional in that the collapse ended early, in 1994, and was followed by rapid recovery. In Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and the Russian Federation, output had reached 80 percent of the 1989 level by 2000, and in Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan, it had reached 70 percent. In both Ukraine (where it had reached only about 50 percent) and Tajikistan (about 35 percent), the recovery had barely started before 2000.

Figure 18.5 GNI per capita as % of 1989 level, 1989–2000. Based on Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, 333. With permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Table 18.1 GNIs of PSIERs, 1989–2008, taking 1989 as base

| Country | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

| Russian Federation | 100 | 100 | 98 | 85 | 80 | 72 | 70 | 68 | 70 | 66 | 72 | 82 | 89 | 95 | 103 | 116 | 127 | 141 | 158 | 172 |

| Mongolia | 100 | 96 | 93 | 84 | 68 | 72 | 96 | 99 | 104 | 109 | 113 | 115 | 121 | 126 | 136 | 153 | 162 | 180 | 203 | 223 |

| Belarus | 100 | 102 | 94 | 89 | 80 | 73 | 77 | 88 | 96 | 102 | 110 | 118 | 128 | 140 | 162 | 184 | 209 | 232 | 261 | |

| Ukraine | 100 | 98 | 92 | 83 | 71 | 57 | 51 | 48 | 47 | 47 | 48 | 52 | 60 | 65 | 73 | 85 | 90 | 100 | 112 | 118 |

| Uzbekistan | 100 | 98 | 93 | 92 | 93 | 98 | 102 | 105 | 110 | 116 | 122 | 128 | 142 | 155 | 170 | 188 | 206 | |||

| Kazakhstan | 100 | 92 | 88 | 83 | 75 | 71 | 74 | 77 | 78 | 80 | 87 | 103 | 116 | 128 | 141 | 153 | 170 | 186 | 189 | |

| Turkmenistan | 100 | 102 | 98 | 92 | 83 | 70 | 63 | 59 | 54 | 56 | 64 | 73 | 91 | 106 | 127 | 150 | 164 | 187 | 212 | 233 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 100 | 108 | 101 | 88 | 76 | 61 | 58 | 63 | 68 | 68 | 70 | 74 | 82 | 82 | 89 | 96 | 99 | 107 | 118 | 127 |

| Tajikistan | 100 | 100 | 95 | 67 | 56 | 44 | 38 | 31 | 33 | 35 | 36 | 36 | 43 | 47 | 52 | 60 | 65 | 70 | 77 | 85 |

| Azerbaijan | 100 | 81 | 71 | 72 | 78 | 86 | 92 | 99 | 110 | 122 | 138 | 152 | 187 | 255 | 314 | 368 |

Source: Based on Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, 333, from World Bank figures. With permission of John Wiley & Sons.

These figures suggest that recovery depended less on the extent of market reforms than on the maintenance of strong, stable state structures. The eventual recovery was rapid in several countries where economic reforms stalled, but there was no political breakdown, including Uzbekistan, Belarus, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan. The recovery was weakest in Tajikistan (which broke down in civil war), and in Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan (in both of which political divisions weakened the state, and made it difficult to introduce coherent economic policies). Mongolia is exceptional because here market reforms were introduced more enthusiastically than in any of the PSIERs, and by a relatively stable and democratic state, and the recovery came exceptionally fast. At the other extreme, Turkmenistan provides another exception to the general rule. Here, there was little political or economic reform, and no political breakdown, but recovery was slow. That may be a hint that even the Chinese reform model required taking market forces seriously. Turkmenistan in the 1990s, like the Soviet Union in the 1970s, still relied primarily on resource revenues (from oil and gas); as late as 2010, only about 25 percent of Turkmenistan's economy was privatized.17

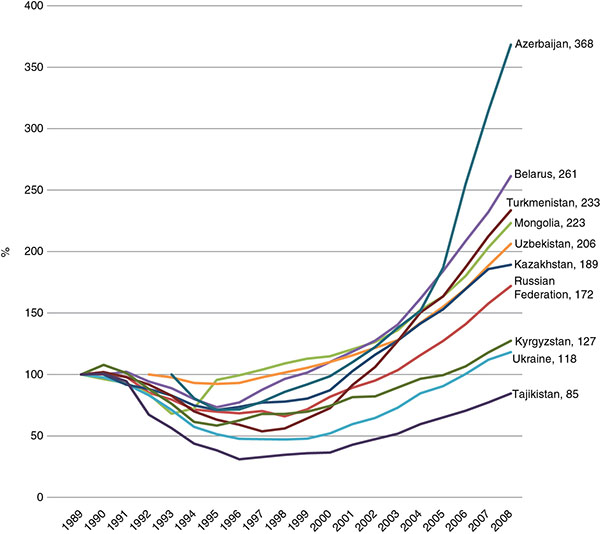

A second important trend, which becomes apparent after 2000, is the close relationship between economic recovery and resource exports. Resource exports offered one of the quickest paths to recovery, and a simple and effective way of entering world markets with limited restructuring of enterprises or the national economy.18 But this strategy depended on having goods such as oil and gas that could be sold profitably on international markets. Among the PSIERs, the four major oil and gas exporters were Russia, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan. In all four, the beginning of recovery coincides with an upturn in global oil prices from 1998, combined with a sharp fall in the value of most PSIER currencies after the 1998 financial crisis. Increasing resource exports help explain why some of the steepest increases in economic growth in the first decade of the twenty-first century were in countries that undertook the least political and economic reform, in Azerbaijan (whose GNI per capita in 2008 was 368 percent of the 1989 level), and in Turkmenistan (233 percent), followed by Kazakhstan (189 percent). (See Figure 18.6.) Russia, too, relied increasingly on resource rents. A recent estimate suggests that by 2008, Russian Federation rents from oil and gas rose from under $100 billion in 1998 to, respectively, $300 billion and $600 billion in 2008.19 Rents on such a colossal scale reduced the pressure for market reforms in all the PSIERs with significant exportable resources. But such high rents are unlikely to persist, which will eventually pose fundamental challenges to economies that have allowed resource wealth to postpone the task of economic reform.20

Figure 18.6 GNI per capita as % of 1989 level, 1989–2008. Based on Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, With permission of John Wiley & Sons.

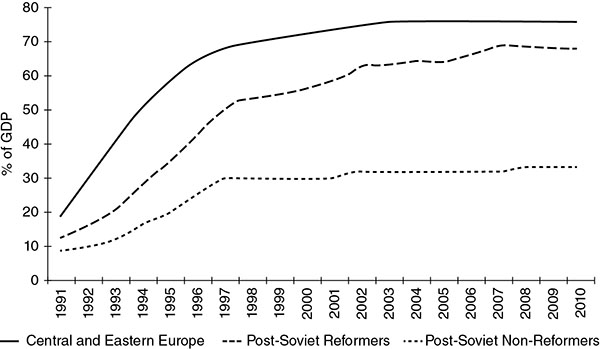

The third large economic trend, in levels and rates of market reform, suggests some reasons for differences in the rate and timing of economic decline and recovery. Figure 18.7provides a rough comparison of levels of privatization, while Figure 18.2 above compares levels of privatization and democratization in 2010. Figure 18.7 shows that the PSIERs privatized later and with less enthusiasm than the countries of central and eastern Europe, in many of which the private sector accounted for almost 70 percent of GDP by the late 1990s. Figure 18.7 also shows that the PSIERs themselves fall into two very different groups. All the PSIERs privatized some industries in the first half of the 1990s, but in Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Belarus, privatization had stalled at under 30 percent of GDP by the mid-1990s, while in the other PSIERs, average levels of privatization had reached about 50 percent by the mid-1990s, and would continue to rise slowly for the next decade and a half, to about 60 percent.

Figure 18.7 Private sector as share of GDP in different groups of post-Soviet societies: the “non-reformers” among the PSIERs were Turkmenistan, Belarus, and Uzbekistan. Aslund, How Capitalism was Built, 191. Reproduced with permission of Cambridge University Press.

Table 18.2 gives the dates at which different countries achieved benchmark levels of price liberalization and trade liberalization. Countries are ranked in descending order, according to the year in which each country reached a score of 4 for price liberalization (the level at which only a small number of administered prices remain). The second column gives the date at which each country achieved a level of 4 for trade liberalization; here, a level of 4 indicates the removal of all major restrictions on imports and exports (apart from agriculture), and of most export tariffs, as well as low levels of government involvement in imports and exports and a convertible currency.

Table 18.2 Years when transition economies reached EBRD scores of 4 for price liberalization and liberalization of foreign exchange and trade

| Country | Price liberalization | Foreign exchange and trade liberalization |

| Hungary | 1990 | 1991 |

| Bulgaria | 1991 | 1994 |

| Czech Republic | 1991 | 1992 |

| Slovak Republic | 1991 | 1992 |

| Croatia | 1992 | 1994 |

| Latvia | 1992 | 1994 |

| Macedonia, FYR | 1992 | 1994 |

| Poland | 1992 | 1993 |

| Estonia | 1993 | 1994 |

| Lithuania | 1993 | 1994 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 1994 | 1995 |

| Romania | 1994 | 1994 |

| Kazakhstan | 1995 | 1996 |

| Armenia | 1996 | 1996 |

| Georgia | 1996 | 1997 |

| Azerbaijan | 1997 | 2005 |

| Belarusa | 1997 | |

| Mongolia | 1997 | 1997 |

| Ukraine | 1997 | 2008 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1998 | 2008 |

| Slovenia | 1999 | 1993 |

| Albania | 2000 | 1992 |

| Russian Federation | 2000 | 1996 |

| Montenegro | 2001 | 2007 |

| Serbia | 2001 | 2009 |

| Moldova | 2005 | 1995 |

| Tajikistan | ||

| Turkmenistan | ||

| Uzbekistan |

EBRD = European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. PSIERs are in bold.

Ranked in descending order by year in which each country reached score of 4 for price liberalization. A score of 4 for price liberalization indicates that only a small number of administered prices remain. A score of 4 for foreign exchange and trade liberalization indicates the removal of all quantitative and administrative import and export restrictions (apart from agriculture) and all significant export tariffs, insignificant direct involvement in exports and imports by ministries and state-owned trading companies, no major non-uniformity of customs duties for non-agricultural goods and services, and full and current account convertibility.

aNote that Belarus reached a score of 4 for price liberalization in 1997, but then dropped.

Source: Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, Table 5.1, 103. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons. EBRD transition indicators available at http://www.ebrd.com/country/sector/econo/stats/timeth.htm

Table 18.2 shows that the PSIERs were much slower than most eastern European and Baltic countries to liberalize prices and trade. Most eastern European and Baltic countries had reached a level of 4 on the index of price and trade liberalization by the middle of the 1990s. But with the exception of Kyrgyzstan, most PSIERs achieved level 4 for price liberalization only in the second half of the 1990s. Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan had not achieved this level even in 2008, while Belarus reached level 4 in 1997, but then fell back to lower levels. The PSIERs lagged even further on measures of trade liberalization. While many reached level 4 in the 1990s, Ukraine and Azerbaijan did not do so until the first decade of the twenty-first century, and Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan had still not reached that level in 2008.

Despite the arguments of the Washington consensus, these graphs show no automatic link between market reform and overall economic growth in the PSIERs. Neither Belarus nor Uzbekistan committed to serious market reforms, but the economic decline ended earlier in these countries (by the middle of the 1990s), whereas in Russia and Ukraine, which committed more decisively to market reform, it ended only after the 1998 crash. Figure , which gives figures on output up to 2008, shows that output per capita continued to rise fast in Belarus and Uzbekistan, despite the absence of serious market reforms, while it rose much more slowly in Russia, and in Ukraine it had barely returned to 1989 levels by 2008. Mongolia is the only PSIER that seems to show a simple correlation between market reforms and economic growth.

Nor is there clear evidence for a correlation between economic growth and levels of democratization. Recovery was slow in both Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan, yet Figures 18.1 and 18.2 (above) suggest that these were among the most democratic of the PSIERs in 2005. Output recovered much faster in Turkmenistan, Belarus, and Uzbekistan, which were the least democratic of the PSIERs according to these charts.

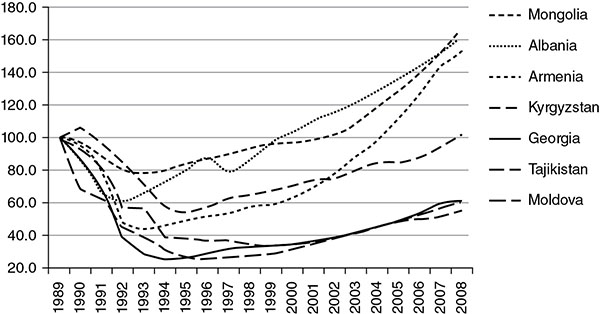

All in all, the degree of institutional breakdown may have had a greater impact on economic production than the degree of market reform or democratization.21 Countries such as Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Belarus preserved many of the institutional structures of the Soviet era; institutional changes were greater in countries such as Russia and Ukraine; while institutions broke down almost entirely in some countries that suffered civil wars. Figure 18.8 suggests that post-Soviet republics such as Moldova, Georgia, and Tajikistan, all of which endured periods of civil war, had the slowest economic recoveries. The other country in which recovery was slow was Kyrgyzstan; here there was considerable early reform, but also significant political instability.

Figure 18.8 Changing GDP in poorer post-Soviet countries as % of 1989 level. Based on Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, 52. With permission of John Wiley & Sons.

The fourth large economic trend, which is obscured by figures on national economic output, is a sharp and universal rise in inequality. Though there was significant inequality in power and access to wealth in Soviet societies, material inequalities were limited because the wealthy could not own significant assets (even if they could control them), while at the lower end of the scale, most people enjoyed high levels of job security, an extensive welfare net, and subsidized prices for basic goods, including rents and heating.

With the breakup of the Soviet Union, inequality and poverty increased sharply in all post-Soviet republics. The World Bank estimated that between 1988 and 1998, the number of people living on less than $2.50 a day in all post-Soviet republics rose from about 2 percent to 21 percent. The numbers living in dire poverty rose fast as unemployment increased, subsidies were cut on rents, heating, and basic foodstuffs, and inflation slashed the real value of wages and pensions. In Russia, average real wages in August 1998 (at the height of that year's financial crisis) were a third of the level for late 1991.22

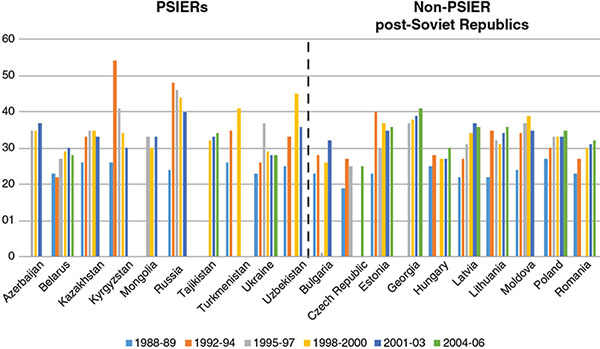

Gini coefficients provide a crude measure of income inequality. They range between 0 (perfect equality) and 100 (perfect inequality, an economy in which one individual owns everything). In 1988–1989, according to World Bank data, the Gini coefficients for all Soviet-bloc countries fell within a range from 19 to 27; 10 years later, all had risen above 26, but the highest rates were in some of the PSIERS, particularly in the mid-1990s, after which the coefficients fell slightly. Nevertheless, in Russia, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, Gini coefficients had risen above 40 by 2000, equaling the highest levels in major industrialized countries such as the USA. In Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan they had also risen to the mid-30s. (Table 18.3a, b and Figure 18.9.)

Table 18.3a, b Gini coefficients for selected post-Soviet republics, 1988–2006

| (a) | ||||||||||

| Year | Azerbaijan | Belarus | Kazakhstan | Kyrgyzstan | Mongolia | Russia | Tajikistan | Turkmenistan | Ukraine | Uzbekistan |

| 1988–1989 | 23 | 26 | 26 | 24 | 26 | 23 | 25 | |||

| 1992–1994 | 22 | 33 | 54 | 48 | 35 | 26 | 33 | |||

| 1995–1997 | 35 | 27 | 35 | 41 | 33 | 46 | 37 | |||

| 1998–2000 | 35 | 29 | 35 | 34 | 30 | 44 | 32 | 41 | 29 | 45 |

| 2001–2003 | 37 | 30 | 33 | 30 | 33 | 40 | 33 | 28 | 36 | |

| 2004–2006 | 28 | 34 | 28 | |||||||

| (b) | ||||||||||

| Year | Bulgaria | Czech Republic | Estonia | Georgia | Hungary | Latvia | Lithuania | Moldova | Poland | Romania |

| 1988–1989 | 23 | 19 | 23 | 25 | 22 | 22 | 24 | 27 | 23 | |

| 1992–1994 | 28 | 27 | 40 | 28 | 27 | 35 | 34 | 30 | 27 | |

| 1995–1997 | 1 | 25 | 30 | 37 | 31 | 32 | 37 | 33 | ||

| 1998–2000 | 26 | 37 | 38 | 27 | 34 | 31 | 39 | 33 | 30 | |

| 2001–2003 | 32 | 35 | 39 | 27 | 37 | 34 | 35 | 33 | 31 | |

| 2004–2006 | 25 | 36 | 41 | 30 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 32 | ||

Source: Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, 349, based on World Bank figures. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Figure 18.9 Gini coefficients for selected post-Soviet republics, 1988–2006. Based on Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, 349, from World Bank figures. With permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Measures of changing income levels can be deceptive, mainly because in the Soviet era and to some extent even in the 1990s, incomes were not the best measure of access to resources. Particularly in the PSIERs, many loss-making enterprises continued to receive subsidies, so that, even if wages fell or were not paid for long periods, employment rates did not fall as fast as in eastern Europe, and housing and basic supplies were protected for many workers. Barter also protected living standards for many in the 1990s. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that levels of inequality rose extremely fast, and millions of people who would have been protected from extreme poverty in the Soviet era lost that protection. Rising inequality helps explain the persistent nostalgia for Soviet times in all the PSIERs.

THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION: A DIMINISHED HEARTLAND

The large trends considered in the previous section will help make sense of the different histories of the various PSIERs. The rest of this chapter will describe the rebuilding process in the Russian Federation.

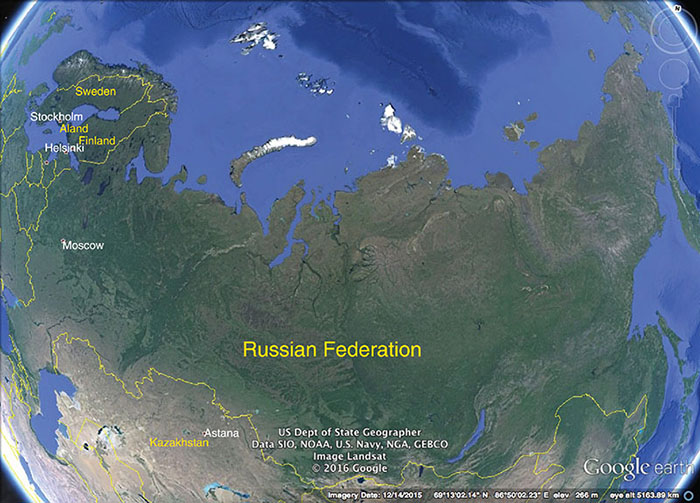

Though diminished in size, wealth, and global influence, the Russian Federation dwarfed all the other PSIERs (Map 18.1). Its size, economic weight, and close connections with the former Soviet bloc and the old imperial heartland ensured that it would continue to act as Inner Eurasia's heartland power. However, particularly in Mongolia and Central Asia, it had to share that role with a resurgent China.

Map 18.1 Google Earth map of the Russian Federation.

Russia was the heir to Russian national traditions, so that building new forms of legitimacy was a less difficult and less urgent task than in the other PSIERs, though Russia did have to deal with the painful challenge of giving up its status as a superpower. Like all the PSIERs, Russia abandoned Marxism as a legitimizing ideology. In its place Russia's new leaders adopted a pragmatic combination of Russian orthodoxy (with church leaders playing a prominent role in state rituals), Russian nationalism, and nostalgia for the Soviet past. Immediately after the Soviet collapse, the primary tasks were to build a market-based economy and new institutional structures. Because the intense reform debates of the perestroika era had mostly taken place in Russia, this was the only PSIER whose leaders entered the post-Soviet era with relatively coherent ideas about reform. Only in Moscow did the reform debates generate real momentum for reform, and only here did the new leader (Boris Yeltsin) owe his position to his advocacy of reform.

1992–1995: THE ERA OF REFORM

Plans for a rapid transition to a market economy were already in the air in 1990. Polish reforms offered an influential model, supported strongly by advocates of the “Washington consensus.” There were both political and economic arguments for moving fast. Shock therapy promised a quick transition to “normality.” Reformers hoped that rapid reforms would create viable market economies before opponents could mobilize to block reform or build powerful rent-extracting empires. Reformers also hoped that a quick transition would limit the pain. After a short, sharp shock, they argued, markets would revive, and benefits would start “trickling down” to the population.

Poland led the way in January 1990. Under the Balcerowicz program, most prices were liberalized, the currency was devalued, and controls on imports were removed. The pain was immediate. Prices doubled within a month, while wages fell by almost 40 percent and total production by a similar proportion.23 In Russia, in mid-1990, a group of pro-market economists including Stanislav Shatalin and Grigorii Yavlinskii proposed a similar program, the “500-Day” Plan. In November 1991, the Russian parliament granted Yeltsin the right to rule by decree, and he used these powers to launch radical market reforms early in 1992, relying on his prestige as Russia's first elected leader and the most visible opponent of the August 1991 coup.

The dramatic simplicity of shock therapy was very much in Yeltsin's style. He is supposed to have approved of the 1990 “500-Day” reform plan without reading a word of it, impressed by its “zippy title and taut timetable.”24 He launched the 1992 reforms with the support of a group of radical young economists, of whom the best known was Egor Gaidar (1956–2009), a Soviet-trained economist who had taken to Friedmanite economic theory with a convert's zeal.

Gaidar saw shock therapy as a necessary evil to prevent the greater evil of total breakdown followed, perhaps, by a civil war as bloody as that of 1918–1921. After his death, the Economist commented:

By the winter of [1991] Russia had two months’ worth of grain left, and producers were refusing to sell their crops to the state at regulated prices. Shops were empty. There was no money to import food, either: foreign-exchange reserves stood at $27m and the country's foreign debt, inherited from the Soviet Union, was $72 billion. The only option for Mr Gaidar and his team was to abolish price regulation and allow free trade.25

In November 1991, Yeltsin told Russia's Supreme Soviet that “The time has come to act decisively, firmly, without hesitation … A big reformist breakthrough is necessary.”26 Yeltsin argued for rapid price liberalization (which would mean sharp price rises); stabilization of the currency and a balanced budget (which would threaten jobs in heavily subsidized industries, and cut welfare payments); and rapid privatization (a complex process for which there were no good precedents). Privatization would be managed by another young pro-market economist, Anatolii Chubais. Yeltsin promised that the pain would be brief. “Everyone will find life harder for approximately six months, then prices will fall and goods will begin to fill the market. By the autumn of 1992 the economy will have stabilized.”27

In November and December of 1991, the government began issuing the relevant reform decrees. One provided for the deregulation of 80 percent of producer prices and 90 percent of consumer prices. Energy prices and transportation prices were excluded, as were some basic foodstuffs such as bread (and vodka), at least for a few months.28 Another decree removed most limitations on the right to trade and to import goods from abroad.

The reforms were introduced on January 2, 1992. To the surprise of many, there was little resistance, despite the fact that prices rose by 250 percent within a day. Inflation cut real wages, erased savings, and destroyed the real value of pensions for millions. Consumers were partially compensated by the disappearance of queues and the reappearance of goods that had not been available for years, including fresh fruit. Removing many subsidies and cutting the military budget by 70 percent eliminated most of the 1991 budget deficit, which had reached 30 percent of GDP.29

The reforms did not halt the decline in production or end inflation. Inflation was caused, in part, because banking systems were chaotic, ill-regulated, and poorly adapted for a market economy. Cooperative banks operated with little regulation and many were linked to (and served the interests of) particular enterprises. Soviet-era politicians ran the central bank and insisted on printing money to keep essential enterprises afloat, to maintain living standards, and to preserve something of the traditional welfare net. Meanwhile, the republican banks of all the other PSIERs continued to print Soviet rubles, so no single government controlled monetary supply. Kyrgyzstan was the first republic to establish an independent currency, in May 1993. In July 1993, the conservative Russian Minister of Finance, Viktor Geraschenko, who had hitherto supported massive subsidies, suddenly declared all Soviet-era bank notes null. This simple measure broke up the common ruble zone, forcing each republic to create its own national currency within just a few months. In principle, at least, inflation could now be tackled separately in each new currency zone.30

Reformers argued that rapid privatization was essential to lock in the reforms. Selling state assets would block a return to the command economy, and allow the formation of new, independent businesses, run and owned by a new class of independent entrepreneurs. But privatization was a colossal and unprecedented challenge. How could you sell off most of the resources of the largest country in the world, and do so fairly, efficiently, and in ways that encouraged entrepreneurial activity? Privatization also had to be fast, because covert privatization had already begun under perestroika, as managers learnt how to extract rents by selling goods manufactured at subsidized prices through cooperatives charging market prices. In the 1990s, such practices came to be known as prikhvatizatsiya, a pun combining the ideas of privatization and robbery with violence (prikhvat’ means to grab). In October 1991, Yeltsin admitted that “Privatization in Russia has gone on for [a long time], but wildly, spontaneously, and often on a criminal basis.”31 The task facing Anatolii Chubais was to formalize, regularize, legalize, and democratize the sale of the assets of the largest country in the world.

The Privatization Program adopted in June 1992 was the last major reform in a hectic six-month period of transformation. Anatolii Chubais opted to privatize by issuing vouchers, nominally worth 10,000 rubles (worth c.US$22 at the time) to every Russian citizen. These could be used at auctions to buy shares in companies, or they could be traded to others. Auctions began in December 1992 and continued until the middle of 1994. In 18 months, over 16,000 large enterprises, each with more than 1,000 workers, were privatized. Many were bought by their own workers, but banks and independent entrepreneurs soon bought up vouchers, and began concentrating control in their own hands. Over 100,000 smaller enterprises had also been sold to private owners, often their former managers. Private housing was, in effect, given to existing tenants. By the end of 1994, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) estimated that more than 50 percent of Russia's GDP was produced in the private sector.32

In the rural sector, privatization was not a success, as few collective farmers were willing to risk going it alone. For all their inefficiency, collective farms, like Mongolian negdels, provided protection. They usually worked closely with local officials, and offered technological, medical, veterinary, and legal services that no other institution could yet provide. Life outside them was tough.

In the abstract, if a collective farm is disbanded, what is left are the hundreds of households that subsist on their so-called “private plots.” The “private plot” is a shorthand for a small holding consisting usually of a house, a vegetable garden, a few livestock pigs and chickens, and rights to a hay meadow where fodder can be cut to sustain the animals over the long winters.33

No private plot had enough resources for a viable independent farm, particularly in an environment where relations with officials, carriers, and wholesalers were monopolized by collective or state farms. As a Buriat economist put it:

The collective farmers under socialism were subject to administrative serfdom. Today they are subject to economic serfdom. Their plots are too small to produce a surplus, and even if they succeeded, there is no public transport now and they cannot take produce to market on their backs. They have to rely on the collective farm to plough their land as they have no machines. That means they have no alternative but to bow to the farm leadership, to give their labor at any rate the boss will offer. The vast majority cannot even escape to the city – they don't have the money to pay to get there.34

From 1993, farming was broadly privatized but collective and state farms survived in the new form of “corporate farms,” which were jointly owned by their members. Many continued to operate as in the past, but gradually the number of smaller individual farms also increased.

Despite their limitations, the economic changes were huge. In just a few years, the private sector, which had barely existed in the Soviet era, accounted for almost 70 percent of Russian GDP. This, argues Anders Aslund, an enthusiast for shock therapy, was “the most fundamental change brought about by the transition.”35

Nevertheless, flourishing competitive markets did not appear overnight. Production continued to fall throughout the 1990s, on a scale comparable to the capitalist Depression of the 1930s.36 By 1995, Russia's total GDP had fallen to about 60 percent of the 1990 level, and by 1998 to about 55 percent before it began rising again. Not until after 2000 did GDP return to the level of 1990, as underused plant and labor began producing again. After 2002, growth owed more to increasing productivity and new capital formation, as well as resource exports, but after the 2008 global financial crisis, Russia's total GDP fell back to just above the 1990 level.37

Inflated Soviet output figures may have encouraged over-estimates of the extent of the decline in production, but figures on physical output show that the decline was real. By 1994, Russian steel production had fallen to 55 percent of 1990 levels, and even in 2003 it had returned to only 70 percent of that level. In Russia, as in most of the PSIERs, the economic collapse was greater than in eastern Europe.38

For ordinary Russians, the results were dire. According to a recent estimate, the number living below officially defined “poverty” levels rose from about 12 percent to about 34 percent (a third of the population) in 1992 alone. The number fell to about 22 percent by 1997, but returned to almost 30 percent during the 1998 crisis, before falling back to about 13 percent by 2010. Average real wages fell by a half between 1992 and 1998, reaching just 150 percent of the official poverty level.39 All too often, wages were simply not paid in the 1990s, though subsidized enterprises protected the living standards of their workers by preserving their rights to accommodation and heating, and even, sometimes, by supplying goods in kind. In the 1990s, the subsidies supplied by enterprises may have equaled almost 10 percent of GDP. Subsidies were particularly important in the more than 400 Russian “monocities” with a single major employer.40

Poverty rates varied greatly between different regions of Russia, and were significantly higher in rural than in urban areas, while in towns, poverty rates were generally higher in smaller towns.41 Government spending on health and pensions fell by between 30 percent and 50 percent between 1990 and 1995.42 The decline in incomes and social welfare inevitably affected health. In 1992, death rates rose above birth rates, and since then the rate of natural increase of the Russian population has been negative.43 By one estimate, life expectancy in Russia in 2005 was two years less than in the 1950s.44 Levels of inequality, as defined by Gini coefficients, almost doubled between 1991 and 1993, rising from about 25 to 43, and reaching levels typical of the more unequal developed capitalist countries. They have stayed at these high levels ever since.45

The breakdown was particularly severe in regions such as Siberia where economic distortions had been most extreme under the command economy. Many enterprises and institutions, and sometimes entire cities, could no longer survive in a world of real market prices. There was widespread impoverishment as military bases closed and subsidies were cut for large enterprises. Without massive subsidies, two of the region's most important sectors, forestry and fishing, turned out to be economically unsustainable.46 By 1999, Siberian economic output had fallen to almost 40 percent of the level in 1990 and infant mortality in the early twenty-first century was twice as high as in Moscow. Many left the region. Between 1990 and 2009, Siberia's population fell by 7 percent and that of the Far East by 20 percent. The population of Magadan fell by 60 percent. Populations increased only in the Tiumen’ region, which flourished after the discovery of huge reserves of natural gas. Siberia's frontier capitalism also generated high levels of crime and corruption; in 2000 Siberian murder rates were three times higher than in Moscow.47

Given the social costs of Yeltsin's reform program, it is not surprising that rising opposition soon brought it to a halt. Within months of its introduction, members of the Russian Supreme Soviet, which was still dominated by former members of the Communist Party, began demanding slower reform and the maintenance of generous government subsidies, even if this meant continued inflation. By the summer of 1992, a strong opposition coalition was emerging, dominated by former communists. Its members insisted on preserving the state's traditional economic role, partly on the grounds that Russian traditions required a strong state, and partly because of the shocking costs of shock therapy, and fear of a slow slide into economic and political anarchy. The opposition was led by Ruslan Khasbulatov, the Speaker of the Russian Supreme Soviet, and a Soviet-era economics professor. He was closely allied to Yeltsin's Vice-President, Alexander Rutskoi, a former fighter pilot. From the middle of 1992, the Supreme Soviet blocked further price liberalization. Similar divisions between market reformers (or “Westernizers”) and supporters of more traditional strategies of rule and mobilization (often described as “statists” or “Slavophiles”) would emerge in many of the PSIERs.

There were strong theoretical, political, and even ethical arguments against shock therapy. Subsidized prices for consumer goods and energy prevented a catastrophic decline in living standards and enabled many enterprises to keep functioning and supporting their workers with housing and supplies. The examples of Hungary and China also suggested that a slower, more carefully regulated process of marketization might work better than Polish-style shock therapy. Besides, many argued that building market economies was not just a matter of introducing universal economic principles and institutions, but required culturally appropriate institutional and legal frameworks, none of which could be created overnight despite the claims of neoliberal economists. Finally, most opponents of rapid reform admired the achievements of the Soviet-era command economies and wanted to preserve their most valuable features.

Reformers responded that it was vital to complete the reforms fast. Without serious privatization and price liberalization, the Russian economy would be left in a sort of economic limbo that limited competition, and allowed rent-takers to exploit artificial price differentials and stymie genuine market activity. As the experience of the NEP era had already suggested, an economy suspended half way between the market and the command economy could flourish in neither. The limits of price liberalization were already reducing pressure on enterprises to introduce efficient practices and technologies. And well-placed individuals were already making huge fortunes by acquiring goods and assets at subsidized state prices and selling them at market prices.

Reformers insisted that half-hearted reforms could only encourage corruption. And corruption was indeed flourishing in an environment where connections and bribes counted for more than innovation or efficient management, creating an entire class of rent-takers dominated by an uneasy alliance of officials from the Soviet nomenklatura and canny new entrepreneurs from the post-Soviet class of “oligarchs.”

Holding the levers of industrial production in their hands and threatening the collapse of industry, managers were able to demand subsidized credits from the government. They received the credits, made money from government subsidies rather than profits in the market, and socked their money into Swiss bank accounts and foreign investments. In one notorious case, the president of Lukoil, who had no real assets in 1991, increased his worth to $2.4 billion by 1995. In monopoly conditions managers set prices as they wished, further fueling inflation. Corruption, bribery, and criminality became part of the fabric of daily life in Russia. One report prepared for Yeltsin in January 1994 claimed that criminal mafias controlled in some fashion 70 to 80 percent of all business and banking.48

The so-called “Komsomol” economy provides a good example of these methods. The Soviet-era youth organization, the Komsomol, enjoyed high prestige and controlled large assets. During perestroika, institutions generally found it easier to trade than individuals, and Komsomol officials became adept at exploiting their power, often in partnership with young businessmen such as Mikhail Khodarkovskii, who would become one of the richest of the oligarchs.49 Komsomol officials and their partners set up commercial banks and construction companies, and soon dominated entertainment, the video market, and tourism, earning massive revenues as they did so.50

Official connections mattered because officials had the power to license or to block new commercial ventures and to control the rules under which they operated. They could also determine the terms on which state property was sold. In some cases entire ministries were privatized, leaving their former ministers as major shareholders.51 Many government officials, including Viktor Chernomyrdin, the founder of Gazprom, the former Ministry of the Gas Industry, became extremely wealthy in this way. The new generation of oligarchs mostly made their money in partnership with influential government officials.

Oligarchs built their business empires by making use of their links to state officials, allowing them to obtain various sources of income – including government subsidies, preferential access to foreign exchange, allocation of export quotas, and provision of preferential import tariffs – and also state property. Thus, they typically made their first millions through commodity trading, importing scarce goods or financing brokering.52

Meanwhile, the government was losing its grip on the economy. After 1991, the oil industry was in such chaos that output almost halved, slashing both state and commercial revenues. Strikes by unpaid workers shut down entire oil fields, oil was stolen and sold illegally, enterprises in oil-producing regions set up as independent businesses. Often it was not clear who really owned the oil or the infrastructure needed to pump, refine, and transport it.53 During the economic reforms, the government tried to take control of the industry so as to organize its eventual privatization. Three large oil companies were created: Lukoil, Yukos, and Surgut, each operating like most other large oil companies by linking exploration, production, refining, and marketing within a single organization, and each marked for slow privatization once it had managed to regain control over its many subordinate companies. But enforcing control was not easy, and sometimes involved local wars between officials, police, and gangs.

There was violence at every level, as Russian mafias – gangs, scarily tattooed veterans of prison camps, and petty criminals – ran protection rackets, stole crude oil and refined products, and sought to steal assets from local distribution terminals. As the gangs battled for control, a contract, all too often, referred not to a legal agreement but to a hired killing. In the oil towns, the competing gangs tried to take over whole swaths of the local economy – from the outdoor markets to the hotels and even the train stations.54

Similar battles for control occurred in other sectors of the economy, too, including the media. And the ever-closer symbiosis between officials and entrepreneurs began to generate fantastic levels of wealth. Courts could do little to prevent corruption given the absence of a strong tradition of judicial independence, low pay for judicial officials, which invited bribery, and the extreme difficulty of interpreting a rapidly changing and often contradictory body of commercial and criminal law. Indeed, with commercial law itself in a state of flux, it was impossible to engage in business of any kind without breaking some laws, and this exposed all entrepreneurs to blackmail. As trade took off, gangs offered “protection” to cafés, owners of market stalls and kiosks, and small shops in return for regular payments. Most gangs were organized under a “roof” or krysha, a powerful gangster or official who protected them in return for a share of their revenues. In 1993, a St. Petersburg gang with about 100 members lived well off the takings from 60 firms, including brothels. The gang assigned a “bull” to patrol markets at night, and the bull expected to graze on the market's produce and services.55 In the 1990s, most entrepreneurs needed a roof, but in the late 1990s levels of criminality began to decline as the government re-established its authority and criminal gangs were squeezed out (or sometimes hired) by legal security companies.

The challenge of dealing with these problems was complicated by widening divisions within the new ruling elite. At the end of 1992, faced with growing opposition to economic reforms, Yeltsin sacked Gaidar as Prime Minister and turned to an experienced politician from the Soviet nomenklatura, the former gas industry boss, Viktor Chernomyrdin. The Supreme Soviet accused Yeltsin of dictatorial behavior (Khasbulatov described him and his colleagues as a “collective Rasputin”) and tried to rescind his right to rule by decree. Yeltsin and his colleagues accused their opponents of blocking reforms that limited their own access to Soviet assets.

Russia's Soviet-era constitution offered no clear way of resolving these tensions between the President and the Supreme Soviet, so the deadlock generated a constitutional crisis. In September 1993, Yeltsin dissolved the Supreme Soviet, in a move that was technically illegal. The Supreme Soviet ignored the order and announced that the President had been replaced by the Vice-President, Rutskoi. On October 3 and 4, supporters of the Supreme Soviet tried to take over the radio station at Ostankino to publicize their cause. Yeltsin brought in tanks to bombard the Supreme Soviet in the so-called “White House,” where, just two years earlier, he had defied the August putsch (Figure 18.10). The bombardment cost several hundred lives. It was particularly shocking because this was the first time military force had been used in an internal conflict since the Civil War.56 Rutskoi and Khasbulatov were arrested. Western leaders were strikingly generous in their assessments of Yeltsin's handling of the crisis, partly because Yeltsin's opponents seemed even less democratically inclined than Yeltsin himself, while Yeltsin's supporters at least seemed committed to market reform. Whoever won, it was becoming clear that a strong government would be needed to manage change. Both sides now understood this.

Figure 18.10 Tanks firing on the “White House,” the home of the Russian Supreme Soviet, October 4, 1993. Courtesy of Peter Turnley. Reproduced with permission of Getty Images.

The conflicts of 1993 could have gone either way. A successful anti-Yeltsin coup might have brought Rutskoi to the presidency on an anti-reform platform, perhaps in alliance with the revived Communist Party. That outcome would surely have slowed the pace of reform even further. But even Yeltsin's violent victory would concentrate more power in the hands of the President. However, Yeltsin's success ensured that in Russia, at least, there would be no fundamental retreat from the economic reforms of 1992.

Yeltsin drafted a new constitution under which the President enjoyed increased powers, including the right to choose the Prime Minister. Izvestiya described the new form of government as a “Super-Presidential Republic.” Yeltsin conceded in an interview, “I don't deny that the powers of the President in the draft constitution are considerable, but what do you expect in a country that is used to tsars and strong leaders?”57 With some changes, the 1993 constitution remains in force today. It replaced the Russian Supreme Soviet with a two-house parliament. The lower house, the Duma, contained 450 members, half elected by a majority in individual constituencies, the other half distributed to parties on the basis of their overall proportion of votes. The upper house, the Council of the Federation, contained two members from each of the Federation's 89 republics. Parallels with the 1906 Fundamental Laws were hard to miss, and some described Yeltsin as a “President-Tsar.”58

By 1994 many key features of the Russian Republic's modern economic and political system were already in place. The price system was largely unregulated, and a significant proportion of productive assets was privately owned. The government was evolving as a parliamentary system with a strong President and limited or ambiguous division of powers. Most Russians understood that things could have been worse. After all, the Russian Federation did not fall apart, there was no civil war, and the economy did not collapse completely.

1995–2000: CONSOLIDATION AND STABILIZATION

But partial economic reform and a new constitution did not guarantee stability. In the mid-1990s, the Russian government faced three main dangers: (1) a war in Chechnya that threatened to break up the Russian Federation; (2) a resurgent Communist Party, and a new nationalist party under Vladimir Zhirinovskii, both of which threatened to roll back reform; and (3) a corrupt and stagnant economy.

The centrifugal forces of the reform era had loosened Moscow's grip on the Russian Federation's 89 provinces and autonomous regions. Indeed, before the final collapse of 1991, Yeltsin himself had invited non-Russians to “seize as much sovereignty as you can handle.”59 Particularly in non-Russian regions, many local leaders took him at his word. In Kazan’, the capital of Tatarstan, Mintimer Shaimiev, the First Secretary of the regional Communist Party, supported the August 1991 putsch, and ignored Yeltsin's economic reforms.60 He ran Tatarstan through a network of relatives he had placed in key political or business positions, many of whom were elected to the regional parliament.

Fearing that the Federation itself might disintegrate, Yeltsin negotiated a “Federation Treaty” in 1992, which kept most regions, including Tatarstan, within the Federation. The methods he used to bring regional leaders into line illustrated the extent to which Yeltsin was already “managing” Russia's young democracy. A 1997 Moscow Times article reported that Kirsan Iliumzhinov, the millionaire businessman and leader of Kalmykiia, was disciplined in 1993 by government threats to expose the corrupt methods he had used to build up his fortune. The threats persuaded Iliumzhinov to accept the authority of the federal government, adding, helpfully, that “everything good” comes from the “center.”61

But these methods did not work in Chechnya. Here, Jokhar Dudaev, a former officer in the Soviet armed forces, who had been deported to Kazakhstan as a child along with most of the Chechen population, had been elected leader by a council of elders. In the Caucasus, the problems Tsarist governments had failed to solve in the nineteenth century remained unsolved at the end of the twentieth century. Dudaev rejected Yeltsin's Federation Treaty, and demanded real independence. In December 1994, over the opposition of the Russian Duma, Yeltsin sent in troops. The Russian army, demoralized and weakened by cuts in funding, performed badly. Casualties were high, and the invasion ended in a stalemate. In 1996, Yeltsin negotiated a humiliating withdrawal, leaving Chechnya's status, and that of the entire Federation, unclear until 1999, when the situation was clarified during a brutal second Chechen war launched in August 1999 and managed by Yeltsin's eventual successor, Vladimir Putin.

Equally dangerous for Yeltsin himself and for the entire process of reform was the rising power and influence of political parties that looked back fondly to the Soviet era. Most important were the revived Communist Party of the Russian Federation (or KPRF), under Gennadii Ziuganov, and Vladimir Zhirinovskii's “Liberal Democratic” party, which was neither liberal nor democratic, but essentially nationalistic in its ideology. In parliamentary elections held in December 1993 under the new Yeltsin constitution, Zhirinovskii was the main winner, followed by the Communist Party. In the 1995 parliamentary elections, Yeltsin's opponents secured well over 50 percent of the vote, and it began to seem that the communist leader, Gennadii Ziuganov, might win the 1996 presidential election, returning a partially capitalist Russia to communist rule.

By early 1996, Yeltsin's popularity had fallen to its lowest level. His public performances, sometimes fueled by alcohol, were bizarre and embarrassing, and his health seemed to be failing. However, Yeltsin decided once again to stand for election. He had the support of the West, which still saw him as the most democratic and market-oriented candidate for the presidency. He was supported by most of the administration, and by the wealthy emerging group of oligarchs, some of whom now controlled large sections of the media. He could also count on significant support from the army and the siloviki, or “power ministers,” who had supported him in his conflicts with the Supreme Soviet. He remade himself, losing weight and temporarily giving up hard liquor. He forced enterprises to pay overdue wages, and, at the risk of a return to hyperinflation, raised salaries and pensions. Despite widespread nostalgia for the Soviet past, it turned out that much of the population did not relish the prospect of a return to communist rule. To the surprise of many, Yeltsin won the 1996 presidential election decisively. In the first round of the 1996 election, Yeltsin gained 35 percent of the vote and Ziuganov 32 percent; in the runoff election in July, Yeltsin gained 54 percent and Ziuganov 40 percent.