[19]

1991–2000: BUILDING NEW STATES: BEYOND THE HEARTLANDS

In much of eastern Europe, the task of building a new state with a market economy and a democratic political system was launched with purpose and enthusiasm. Independence came as an exciting, if daunting challenge. In the Russian Federation, too, leaders tackled the task of state building with a clear sense of purpose and direction. But in the other PSIERs, independence arrived unexpectedly and without invitation. New states were cobbled together, and reforms were introduced on the run or resisted. Though some populations, particularly in Ukraine, welcomed independence, the leaders of most of the PSIERs had little enthusiasm for reform, and struggled to find their balance in unfamiliar and rapidly changing surroundings. Sally Cummings writes of Kazakhstan,

Kazakhstan was born by default. The republic's independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 was neither the result of secessionist demands by its leadership, nor a national liberation movement; it resulted from the decision by Moscow to withdraw its maintenance of the Soviet edifice.1

The strategies and decisions taken by the new leaders were shaped, as in Russia, by Soviet traditions of governance, because most of the new leaders had learned their trade within the Soviet nomenklatura. This explains many similarities in the histories of the new states, in particular their almost universal drift back towards centralist styles of government and economic management. But their histories were also driven by ancient geographical, historical, and cultural differences; by the geopolitics of a capitalist world that was larger, more complex, and more dynamic than the Soviet Union; and by the sometimes off-the-cuff decisions of individual leaders and the unexpected contingencies of a fast-moving environment. Despite some common features, the histories of the PSIERs also diverged in many important respects.

This chapter will survey the histories of the non-Russian PSIERS, before 2000, with the occasional glance beyond that date. It will begin with the Slavic republics, Belarus and Ukraine, then move on to the Central Asian republics. It will end by discussing Xinjiang and Mongolia, two regions that had not formally been part of the Soviet Union but were part of Inner Eurasia.

THE SLAVIC REPUBLICS: UKRAINE AND BELARUS

Despite cultural similarities, and shared historical traditions, Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine would take very different paths in the post-Soviet world.

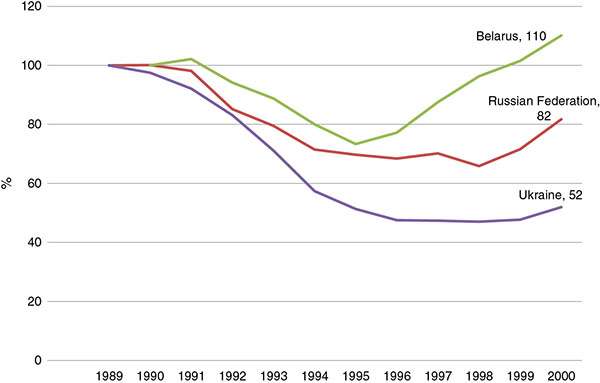

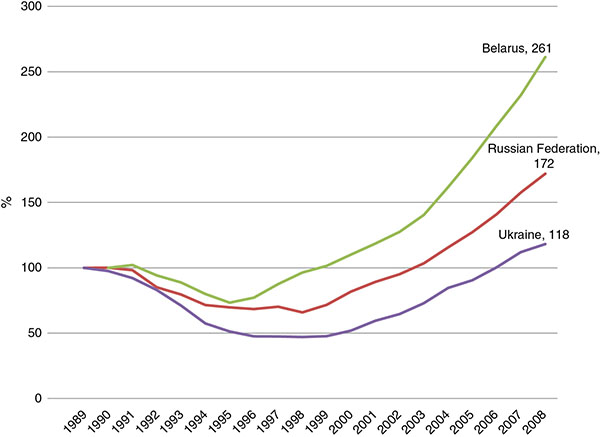

Even their patterns of decline and recovery were different. Of the three Slavic republics, Belarus took the fewest steps towards political or economic reform, and retained strong, centralized state structures, but suffered the smallest economic decline and enjoyed the fastest recovery. Russia undertook significant economic and political reforms, and retained relatively strong state structures, but its economic decline was greater, and its recovery later than in Belarus. Finally, Ukraine introduced significant political and economic reforms, but they were managed by a weaker, more divided, and less stable state, and this may help explain why Ukraine's economic decline went further, and its recovery came later than in Belarus or Russia. (Figures 19.1 and 19.2.)

Figure 19.1 Changing GNI of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, 1989–2000 as % of 1989 level. Based on Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, 333, from World Bank figures. With permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Figure 19.2 Changing GNI of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, 1989–2008 as % of 1989 level. Based on Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, 333, from World Bank figures. With permission of John Wiley & Sons.

UKRAINE

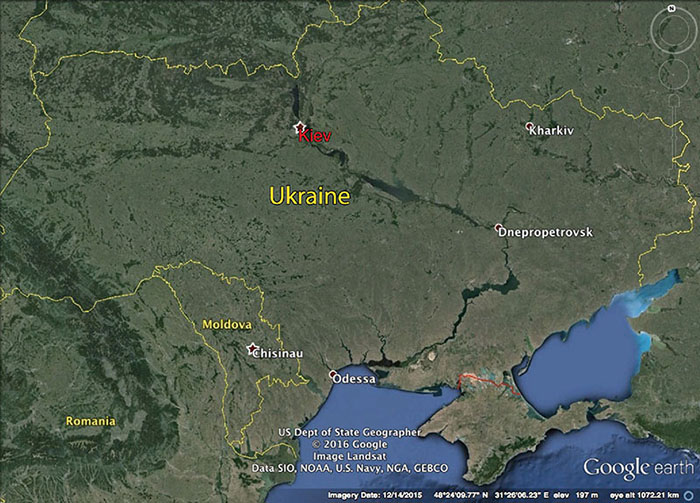

Modern Ukraine has a population of almost 50 million, and an area larger than any western European state (Map 19.1). Russian historians have generally treated Ukraine as the homeland of Rus’, and an integral part of Russia and Russian history, while Russian linguists have generally regarded Ukrainian as a dialect of Russian. But Ukrainian scholars, such as the great nineteenth-century historian Mykhailo Hruhshevsky, saw Ukraine as a distinct nation, with an independent national history and a language of its own.

Map 19.1 Google Earth map of Ukraine.

Ukraine's various regions were incorporated piecemeal into the Russian Empire from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries up to the Stalin era. East of the Dnieper river, Ukraine included much of the Pontic steppes, regions that had once been controlled by the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean khanate, but had then been settled by Cossacks and Ukrainian and Russian soldiers and farmers, before becoming a major industrialized region in the late nineteenth century. West of the Dnieper, Ukraine reaches into Podolia and Volhynia, which had been parts of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, into Galicia in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, and even into regions on the shores of the Black Sea that had been part of the Ottoman Empire. Today, most Ukrainians who identify as Russian live east of the Dnieper (the most Russian-dominated region is the Crimea), and most who identify strongly as Ukrainian live in western Ukraine. There are also significant Polish and Jewish minorities and other, smaller ethnic groups.

Geographically, historically, and culturally, Ukraine (“Borderland”) straddles the borders between Inner and Outer Eurasia, and that simple geographical fact would dominate Ukraine's post-Soviet history. Generally speaking, its western regions looked towards Europe, while its eastern regions looked towards Russia and Inner Eurasia.

Modern forms of Ukrainian nationalism arose in Kiev and in Ukraine's western regions, amongst a Ukrainian intelligentsia that emerged in the nineteenth century. By the late nineteenth century, Ukrainian nationalism was influential enough to provoke Tsarist repression. An independent Ukrainian state existed briefly during the years of revolution and civil war, and, though Ukraine did not survive as an independent state, it did survive as a distinct Soviet republic during the Soviet era, so some of the structures and forms of statehood survived. Ukrainian nationalism was suppressed for most of the Soviet era, but revived, like many other regional nationalisms, in the era of perestroika and glasnost’.

Like many colonial borders, those of Ukraine, as drawn up in the early 1920s, complicated the task of nation building, because those who identified as Russian were almost as numerous as those who identified as Ukrainian. This ensured that tensions between competing ideas of Ukrainian statehood would muddy attempts at state building and reform. At the time of writing (2017), these divisions, which once seemed manageable, have ignited a slow-burning civil war in the Russian-dominated eastern regions.

In the late 1980s, even many who did not identify primarily as Ukrainians supported the idea of Ukrainian independence. The nuclear accident at Chernobyl in April 1986 highlighted Kiev's dependence on decisions taken in Moscow. In February 1989, the Taras Shevchenko Ukrainian Language Society emerged as one of the first large organizations not under the direct control of the Communist Party. Revelations were published about the fate of Ukrainian nationalists during the purges, and the collectivization famines known in Ukraine as the “Holodomor,” or “Death by Hunger.” There was growing interest in the independent Ukraine of the Civil War years, and in Cossack history, which became a potent symbol of Ukrainianness. The Ukrainian flag appeared at demonstrations in 1989, first in western Ukraine, then in Kiev. In March 1989, there were elections to a Ukrainian Congress of People's Deputies, the Verkhovna Rada. Informal organizations appeared, such as the Ukrainian nationalist organization Rukh. In October 1990, there were pro-independence protests by students on Kiev's central square, the Maidan. In August 1991, just after the failed Moscow coup, the Rada voted almost unanimously for independence, in a declaration that referred to the “thousand-year tradition of state building in Ukraine.”

In December 1991, as the Soviet Union disintegrated, Leonid Kravchuk was elected Ukraine's first President. Though a member of the Communist Party since the 1950s, his own biography reflected Ukraine's checkered past. He was born in Volhynia, on lands that were part of Poland before the Soviet invasion in 1939. He was a long-time member of the Soviet nomenklatura, and the background he shared with other post-Soviet leaders surely eased the task of partitioning the Soviet Union at the end of 1991. Like many regional leaders, Kravchuk did not actively oppose the August 1991 coup in Moscow, but did not support it openly enough to prevent his election as President three months later.

Ukraine's borderland status was reflected in its first steps in foreign policy. It looked both to the east and the west. In 1992, Kravchuk agreed to lease the Sevastopol naval base to Russia for five years, and Russia agreed to maintain flows of cheap oil and gas to Ukraine. But Ukraine also accepted a deal brokered by the USA, to hand over Ukraine's nuclear weapons to Russia, and soon, it was receiving US aid. In 1994, Ukraine became the first post-Soviet state to sign an agreement of cooperation with the European Union (EU).2

Immediately after independence, even many Russian-speaking Ukrainians identified as Ukrainian. On December 1, 1991, more than 90 percent of the population voted for independence. The Ukrainian nationalist organization Rukh even tried, though without much success, to attract Russian members. The issue of Ukrainian identity was in any case subtle and confusing. According to the 1989 census, 73 percent of Ukraine's population identified themselves as ethnically Ukrainian, and 22 percent as Russian, in a total population of 51.4 million. But many who identified as Ukrainian did not nominate Ukrainian as their main language, and less than 50 percent used Ukrainian most of the time. Even in 2001, it appeared that 80 percent of the population used Russian as their “primary language of communication,” while most publications and television programs were still in Russian.3 Widespread use of Russian reflected the dominant role of Russian in the Soviet era, particularly in the towns and the eastern regions. It had been the language of government, of management, of many educational institutions, and most of the media.

Not surprisingly, differences over the nature of a Ukrainian nation emerged early. A 1989 poll of Rukh members showed that 73 percent gave nation building as their first priority while in Ukraine as a whole, only 12 percent put this goal first. In 1990, a symbolic “linking of hands,” joined by 1 million Ukrainians, reached from Lviv in the west to the largely Russian-speaking city of Kiev, but did not extend into eastern Ukraine.4 The size, importance, and geographical concentration of the Russian minority raised many practical problems for the new nation. For example, the Ukrainian army was formed from units of the Soviet army stationed on Ukrainian soil at the end of 1991. About 70 percent of its officers identified as Russian. Where would their loyalties lie in the event of a conflict with Russia, perhaps over the future of Crimea, a Russian-dominated region that had been incorporated within Ukraine only in 1954, under Khrushchev? In 1992, when soldiers and officers of the new Ukrainian army began taking oaths of allegiance to the new state, some 10,000 officers refused the oath, and were allowed to retire or leave for Russia.5

These differences made it risky to insist too strongly, as many Ukrainian nationalists wished, on the new state's “Ukrainianness.” Russian speakers in particular argued for a federal state, with at least two national languages. Yet on the crucial constitutional issue, the nationalists got their way. Chapter 1, article 2 of Ukraine's 1996 constitution declared that, “Ukraine is a unitary state. The territory of Ukraine within its present border is indivisible and inviolable.” Chapter 1, article 10 dealt somewhat ambiguously with the issue of language, giving Russian a secondary status below Ukrainian.

The state language of Ukraine is the Ukrainian language. The State ensures the comprehensive development and functioning of the Ukrainian language in all spheres of social life throughout the entire territory of Ukraine. In Ukraine, the free development, use and protection of Russian, and other languages of national minorities of Ukraine, is guaranteed.

As a result of this article, all official documents, including election documents, had to be published in Ukrainian, a language unfamiliar to many Ukrainians.

Differences over national identity created divisions on many important issues. While Ukrainian nationalists sought a unitary state with strong ties to Europe, many in the Russian-dominated eastern regions sought a federal state with at least two national languages, and continuing ties to Russia. These fundamental divisions created space for genuinely democratic debates, and by the mid-1990s, Ukraine was widely reckoned to be one of the most democratic of the PSIERs. But divisions also weakened the young state and limited its power to develop coherent policies both at home and abroad. The demographic and political balance between the Russian-dominated east and the Ukrainian west yielded governments formed after complex and often difficult negotiations, which involved awkward tradeoffs on policy and personnel, and prevented the development of coherent long-term programs of reform.

These divisions were compounded by the complex challenge of building a post-Soviet economy. Political drift guaranteed drift on economic policy, too. Before 1993, the National Bank of Ukraine issued ruble credits with little restraint, and by 1992, inflation had reached 2,500 percent. Ukraine's GDP fell further than in any of the former Soviet republics except those such as Tajikistan and Moldova that disintegrated in civil war. Yet political divisions made it difficult to formulate coherent strategies for recovery or reform. Apart from Tajikistan, Ukraine would be the last of the PSIERs to return to 1989 levels of production, well after 2000.

The depth and persistence of Ukraine's economic decline had many causes. They included the loss of Soviet orders for Ukraine's huge coal, metallurgical, and weapons industries, most of them in the east. These regions had supplied most of the Soviet defense sector before 1991. Ukraine lost Soviet subsidies, and, with little gas or oil of its own, it had to depend on Russia for most of its energy. The slow recovery also reflected the weakness of a divided state, and its limited control over economic change. Even more than in Russia, half-hearted and contested programs of economic reform created a vast arena for rent-taking and corruption, while a weak state was all too easily co-opted by an increasingly wealthy and powerful class of oligarchs. The central government surrendered much of its economic control to regional councils, factory directors, and farm managers, the very class that had consolidated so much power in the later years of the Soviet era. The power of the regions helps explain the success of Ukraine's oligarchs, many of whom came from regional industrial fiefdoms such as the industrial center of Dnepropetrovsk. This was the home territory of Ukraine's second President, Leonid Kuchma, a former director of a Soviet-era missile factory.

Kuchma, who had been Prime Minister under Kravchuk, replaced his former boss as President in 1994. He launched a significant, and reasonably successful, program of privatization which, like the Russian program, used vouchers issued to citizens, which were rapidly bought up by entrepreneurs. A second round of privatization sold off major assets, often at very low prices, and mainly to Ukraine's emerging business class. Since 1996, most of Ukraine's GDP has come from the private sector, though many of the largest industries remain in state hands. Limits on price liberalization allowed rent-taking, particularly in transactions involving goods such as gas and oil that were subsidized by both the Russian and Ukrainian governments. Continued subsidies allowed huge arbitrage profits, while privatization let entrepreneurs acquire state resources and enterprises at knock-down prices.

Corruption reached from regional oligarchs to the top of the political system. Towards the end of his final term in office, President Kuchma was widely suspected of having arranged the assassination of a journalist investigating high-level corruption. By the mid-1990s, Ukraine's distinct combination of weak central government and powerful regional oligarchs was beginning to create a new ruling elite, dominated by oligarchs with regional bases, and their allies in government. Similar alliances had emerged also in Yeltsin's Russia, but there, under Yeltsin's successor, Putin, a stronger state would eventually bring regional officials and oligarchs into line. In Ukraine, as in Russia, inequality increased. In the late 1990s average levels of inequality in Ukraine were lower than in Russia (Ukraine's Gini coefficient was 29, compared to Russia's 44), but recent estimates suggest that by 2014, 80–85 percent of the nation's wealth was controlled by just 100 people.6 (See Figure 18.9.)

The 1998 economic crisis brought the government close to default, and by 1999, total production had fallen by more than 50 percent since independence. Economic decline took such a severe toll on living standards that Ukraine's population fell from 51.4 million in 1989 to 48.4 million in 2001, as Ukrainians emigrated and mortality rates rose.7 But the economy did not collapse entirely, partly because of subsidized Russian sales of gas and oil: 90 percent of Ukrainian oil and 77 percent of its gas came from Russia, and Ukraine accumulated huge debts. In 2000, Prime Minister Viktor Yushchenko, a former chairman of the National Bank, launched a new round of price liberalization and fiscal tightening. At last the economy began to grow once more, but not until 2008 would Ukraine's GDP surpass the level of 1990. (See Figure 19.2.)

By 2000, Ukraine had a vibrant, if corrupt and lopsided market economy.8 Its relatively weak state and the complex ethnic balance between regions allowed for genuine parliamentary debate and, eventually, for mass protest movements. While politicians tried as hard as their colleagues in the Russian Federation to manage elections and the media, they were generally less successful. In 2004, President Kuchma's hand-picked successor, Viktor Yanukovych, from eastern Ukraine, was elected as President in an election marred by massive corruption. The election provoked enormous protests in Maidan square in Kiev. Protesters denounced vote-rigging and corruption during the election. There was even an attempt to poison Yanukovych's presidential rival, the former Prime Minister, Viktor Yushchenko. Protesters also opposed Yanukovych's pro-Russian orientation, as most of those gathered on Maidan square supported a turn towards Europe and the EU. These protests came to be known as the “Orange Revolution,” after Viktor Yushchenko's campaign colors. In December 2004, Yanukovych's election was annulled, and in January 2005, Yushchenko was elected as President.

In practice, little was achieved during Yushchenko's presidency, as the standoff persisted between different camps within the emerging ruling elite. A constitutional amendment depriving the President of the right to appoint the Prime Minister ensured endless, debilitating conflicts between the country's two leading politicians, Yushchenko and his former ally, another former oligarch from eastern Ukraine, Yulia Tymoshenko.

Despite significant steps towards both democracy and market reform, Ukraine in the early twenty-first century appeared deadlocked, with a weak and divided state unable to take clear long-term decisions about the future. Should it support further market reforms, and ally more closely with (and perhaps eventually join) the EU, at the risk of alienating Russia and losing cheap Russian supplies of oil and gas? Or should it try, like Russia, to build a stronger state structure with greater control over the regions that could manage the economy, perhaps in close partnership with Russia and other former members of the Soviet Union? As it was, political weakness left the management of the economy largely to the whims of a new oligarchy, while uncertainty about Ukraine's international orientation created tension with Russia, the main supplier of Ukrainian energy, without bringing Ukraine any closer to membership of the EU. In 2014, conflicts with Russia would turn into a slow-burning civil war after Russia's annexation of Crimea in March 2014 encouraged pro-Russian nationalists in eastern Ukraine to demand independence for “Novorossiya,” or incorporation with the Russian Federation. The Russian government, keen to appease its own nationalists, has supported them covertly, but to date (2017) both sides have avoided open war.

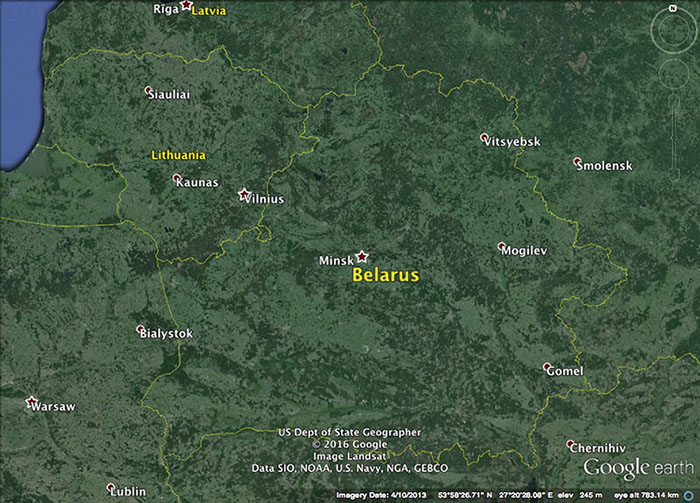

BELARUS

Belarus (Map 19.2), like Ukraine, had strong historical links to eastern Europe, because it had long been part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Belarus also had a brief tradition of independent statehood, as an independent Belarusian People's Republic had emerged after the 1917 Revolution. In 1922, the Socialist Republic of Belarus became a founding member of the Soviet Union. But in Belarus there did not emerge a strong nationalist tradition. Though Belarusian was the republic's official language, Russian was made a second state language in 1995, and it was, in practice, the republic's dominant language, particularly in the cities.9 Most of the Jewish population of Belarus was deported and murdered during the Holocaust, and large numbers of Poles left during the war.

Map 19.2 Google Earth map of Belarus.

Though almost 80 percent of the population was described as Belarusian in a 1989 census, and Russians accounted for just 10 percent, there was little support for Belarusian nationalism.10 A Belarusian National Front (BNF) was established in 1989, but it never became a dominant force in Belarusian politics and had little support within the Soviet-era nomenklatura. With large numbers of churchgoers, particularly in the formerly Polish parts in the west, religion also began to play a role in legitimizing the state, as in Russia. A 2002 law described Orthodoxy as playing a “defining role in the state traditions of the Belarusian people.” In practice, nostalgia for the Soviet era also played a legitimizing role, and periodically encouraged proposals for a closer union with Russia. In a 1991 poll, more citizens of Belarus (69 percent) identified themselves as “citizens of the USSR” than in any other part of the USSR. This complex mixture of legitimizing forces helps explain why Aliaksandr Lukashenka, who has ruled Belarus since 1994, once described himself as an “Orthodox atheist.”11

The absence of serious ethnic divisions helps explain the evolution of a strong, conservative, and relatively unified state structure, despite significant political divisions just after independence. Like most of the Central Asian PSIERs, the government of Belarus would limit both market and democratic reforms. Former Soviet institutions such as the KGB survived the transition well, as did most of the former elite, many of whom belonged to a retitled “Communist Party of Belarus” until 1994. In its resistance to reform after an initial period of experimentation, Belarus suggests what might have happened in the Russian Republic had the Communist Party won elections in the mid-1990s.

During the era of perestroika, there was little serious discussion of reform in Belarus, little political dissidence, and no serious preparation for independence. In the 1990 elections to the new Belarusian Supreme Soviet, communists won most of the 315 contested seats, and the Belarusian National Front or its allies won fewer than 40.12 In April 1991, there were large-scale strikes caused by Moscow's decision to raise prices for basic consumer goods. Though Belarus experienced all the uncertainties of perestroika’s final years, there did not emerge a coherent opposition movement. In the March 1991 referendum on the Soviet Union, 83 percent of Belarusian voters supported continuation of the Soviet Union. The Belarusian Communist Party leader Anatol Malafeew gave his full support to the August 1991 attempted coup in Moscow.

Despite these unpromising signs, in 1991 there were many reasons for thinking that Belarus could have made a relatively easy transition to democracy and a market economy. It was urbanized and had industrialized rapidly after the war; it had small reserves of oil, oil refineries, and metallurgical and fertilizer plants. Its population was well educated, enjoyed some of the highest living standards in the USSR, had few ethnic or religious divisions, and did not suffer extreme income inequalities.13 Yet the republic's rapid development in the later Soviet era may also help explain why nostalgia for the Soviet era would prove a potent force in Belarus.

Real independence came to a reluctant Belarus leadership as a result of the December 1991 meeting at Belovezhkaia in western Belarus between Yeltsin, Kravchuk, and the new Belarus communist leader Stanislaw Shushkevich. In the two years after independence, conflict between Shushkevich and his more conservative Prime Minister, Viacheslaw Kebich, stymied the development of a coherent reform plan. Shushkevich, a scientist, had been elected Party leader as a compromise candidate after the declaration of independence in September 1991. Like Askar Akaev in Kyrgyzstan, another scientist elected as a compromise leader, Shushkevich was weakened by his lack of political experience and connections within the nomenklatura.

In 1992, following the lead of the Russian Federation, the government introduced its own form of shock therapy. It liberalized most wholesale and retail prices and privatized many state enterprises. The result, as elsewhere in the post-Soviet era, was hyperinflation, and the economic free-fall soon generated a powerful political and popular reaction. Like Yeltsin, Shushkevich faced opposition to reform from members of the former Communist Party who dominated the Supreme Soviet. They made the same arguments as Yeltsin's opponents, demanding slower reform, increased protection for state enterprises, and the maintenance of subsidies to support pensions and keep consumer prices low. They also argued that the reforms of the perestroika era had destroyed a great state, and now threatened a new Time of Troubles, of chaos, corruption, and anarchy. In 1993, a year before he was elected President, Aliaksandr Lukashenka criticized “parliamentary anarchy, where everyone just talks, though nobody answers for anything or builds an effective vertical of state power with personal accountability.”14 Such ideas resonated widely, particularly in Lukashenka's milieu of middle-level officials who had risen to power in the Brezhnev era.

In Belarus, unlike Russia, the conservative wing of the ruling elite won the standoff over economic reforms. By 1994, Aliaksandr Lukashenka, a former political outsider and one-time director of a collective farm, had emerged as a leader of the conservatives, and the Prime Minister, Kebich, sought his support both in bringing down Shushkevich and in boosting his own bid for the presidency. Lukashenka first gained prominence as head of an anti-corruption committee appointed by Shushkevich, who soon became one of its main targets. In 1994, in Belarus's only competitive election of a leader (though all sides used dirty tricks), Lukashenka was elected President on a wave of popular hostility to the existing leadership and pro-Soviet nostalgia provoked by the difficulties of economic reform. His successful populist campaign slogan was “Neither with the left nor with the right, but with the people.” It may be that his nomenklatura rival, Kebich, simply failed to use the many resources at his disposal to manage the election successfully, a lesson Yeltsin may have taken to heart during Russia's 1996 election.

Once in power, Lukashenka proved unmovable, and he remains President at the time of going to press (2017). A new 1994 constitution had already increased the powers of the President, but a 1996 referendum would give Lukashenka almost dictatorial powers, including the right to dissolve parliament. Constitutional referenda in 1995 and 1996 gave the President the power to appoint judges to the constitutional court, to appoint to the electoral commission, and to choose members of the upper chamber. Since 1996 the parliament of Belarus has lost any significant role in politics. Lukashenka has largely taken control of the mass media, sometimes using violence and intimidation, and there have been occasional suspicious disappearances of opponents and journalists.15

Market reforms were abandoned, including a 1993 plan for privatization, which was dropped when privatization vouchers had already been distributed. In November 1994, just months after his election, Lukashenka announced on television that he intended to work with the kind of economy he understood, which was a planned economy.16 Price controls were reintroduced, and by the end of the 1990s Belarus had one of the smallest private sectors of all the post-Soviet republics; in 2010, only c.30 percent of GDP came from the private sector.17 Most of Belarus's trade is still with Russia and other former Soviet republics. Particularly important have been subsidized Russian supplies of gas and oil. Like Vladimir Putin, but considerably earlier, Lukashenka consolidated the power of the central government by clipping the wings of oligarchs. Aliaksandr Pupeik, the richest of the Belarusian oligarchs, and head of the country's largest single business, was driven into exile in 1998.18

Despite the end of economic reforms, the country's economy did not collapse, and levels of economic corruption remained lower than in most other republics. Lukashenka's personal popularity seems to have remained high. He consistently argued for the rebuilding of a new version of the Soviet Empire, and made several attempts to form a closer union with Russia. In 1995, a new treaty allowed Russian troops to stay on Belarus's territory and created open economic borders between the two countries, while later agreements allowed Belarus to purchase Russian oil and gas cheaply, and wrote off large Belarusian debts. One element in his popularity may be the maintenance of a highly subsidized welfare system, similar to that of the Soviet era.19 That may explain why Belarus's GINI coefficient has never risen about 30, in contrast to Russia, where it rose to 48 in the 1990s before falling back to about 40 (Table 18.3). But the building of a strong and stable central government has also contributed to his popularity.

The reason why the population supported Lukashenka cannot be explained simply by economic development and stability, but also by the perception of a strong leader whose actions are justified by ensuring the defense from the country's enemies, internally in the form of the opposition and externally in the form of the West and NATO. Here, the economic element coupled with fear of changes perfectly correlates with the Soviet narrative of protecting its population from the “rotten West” and providing the people with all basic needs.20

Lukashenka's strong rule resonated widely with a population that still shared many of the core values of the Soviet era: strong, stable government, limited inequality, and a powerful welfare net.21 Lukashenka has proved extremely successful at building support both within the Belarusian elite and within society at large, and in many ways his rule demonstrates the continued viability of traditional statist methods of rule and economic management in the post-Soviet era.

KAZAKHSTAN, CENTRAL ASIA, AND AZERBAIJAN: 1991–2000

Like the history of Belarus, the history of post-Soviet Inner Eurasian republics in central Inner Eurasia illustrates the durability of traditional centralist methods of rule and economic management in societies where there was little elite or popular enthusiasm for radical economic or political reform.

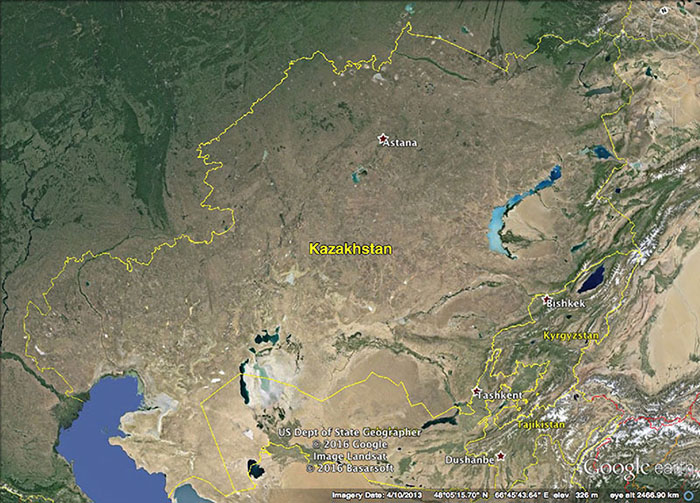

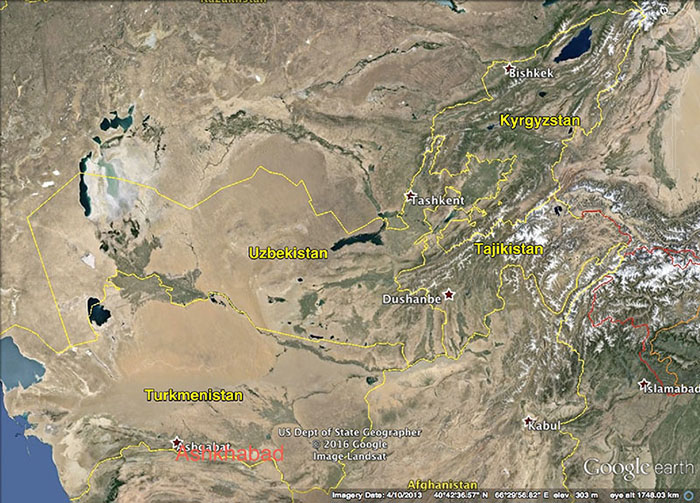

At a summit meeting in Tashkent in January 1993, the term Central Asia was formally adopted as a designation for Kazakhstan and Transoxiana by all five states described in this section: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan (Map 19.3 and 19.4).22 After 1991, it also makes sense to include Azerbaijan with this group of states, because their cultural and historical trajectories had much in common. Kazakhstan is by far the largest of these states, making up almost two thirds of the area of Central Asia, while Uzbekistan is the most populous, with almost 25 million inhabitants.

Map 19.3 Google Earth map of Kazakhstan.

Map 19.4 Google Earth map of Transoxiana.

National borders now criss-cross a region that was previously part of a single Soviet political space. And that makes regional collaboration more difficult than in the past. For example, little has been done to deal with the huge environmental problems of the Aral Sea region, which affect Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan. The coerced collaboration of the Soviet era has been replaced by commercial and political competition between regional polities, so studying Central Asia's history after 1991 means studying it nation by nation. However, there has been some regional cooperation on security issues involving China, through the “Shanghai Cooperation Organization” or SCO. Founded in 1996, this brought together states that shared a border with China: Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan; Uzbekistan joined in 2001. Originally brought together to deal with border disputes and share information on Islamic fundamentalism, that organization may eventually generate new forms of regional collaboration. In 2014, a new Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) was created, linking Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. First proposed by Nursultan Nazarbaev in 1994, it has ambitious plans for economic integration, similar to the EU, but to date (2017) progress has been very limited.

The new republics of Central Asia faced similar challenges after 1991, and their shared past within the Soviet Union ensured they would approach them in similar ways. None had strong opposition movements or democratic traditions, so Soviet-era elites remained in office, bringing with them Soviet habits of governance. Even regional nationalisms had been forged largely during the Soviet era, though new symbols and national histories would soon appear, based on pre-Soviet historical and cultural traditions. There was much in the Soviet legacy that new nations could build on. All the Central Asian republics inherited high educational levels and significant, if lopsided, industrial sectors designed primarily to exploit their main agrarian and industrial resources. By 1991 they were all quite urbanized (except for Tajikistan); levels of urbanization ranged from 35–60 percent. They also inherited strong state structures that survived more or less intact (though they broke down for a time in Tajikistan). But Marxist ideology vanished, and Soviet-era elites began to align themselves cautiously with Muslim religious and cultural traditions as they sought new forms of legitimacy.

At first, the influence of Russia and of Russians really mattered. Most of the new leaders had been members of the Soviet nomenklatura, and all were profoundly Russified. With the exception of Askar Akaev in Kyrgyzstan, the first Presidents of the Central Asian republics were all former Communist Party First Secretaries, and most sympathized with the goals of the August 1991 coup.23 Akaev was the only regional leader to openly oppose the coup. Russian influence was particularly important in Kazakhstan, almost 40 percent of whose population was Russian in 1991, and in Kyrgyzstan, 21 percent of whose population was Russian. In both republics, it was the northern regions and the largest cities that were most Russianized. In Tajikistan, the government would depend for several years on Russian and CIS troops to defend itself against internal opponents and armed Islamic incursions from Afghanistan.24

But Russian military, cultural, demographic, and economic influence waned as the Central Asian republics developed new international economic and diplomatic ties, and as many Russians left Central Asia for the Russian Federation. Ten years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and immediately after the September 11, 2001 attacks on the USA, the US government negotiated agreements with Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan allowing it to establish military bases. In December 2002, Russia had to negotiate separately to establish a base of its own in Kyrgyzstan, not far from the newly established US military base. Here was a powerful reminder that the Soviet Empire really had ended in 1991, despite continuing Russian economic and political influence throughout Central Asia.

During the era of perestroika, Central Asian politicians and managers had faced a flood of new edicts from the center, on the management of enterprises, on press censorship, and on the changing role of the Party. But real change was limited, and perestroika and glasnost’ generated none of the ferment of debate that energized intellectuals and politicians in Moscow, Leningrad, and other major Russian cities. Nevertheless, the slow relaxation of the center's grip did release pent-up resentments. When Gorbachev replaced the Kazakh leader Dinmukhamed Kunaev with a Russian, Gennadi Kolbin, in December 1986, he was shocked that what had seemed a minor bureaucratic reshuffle provoked violent riots in Almaty, during which several people were killed. In Ferghana, which had an exceptionally diverse population, partitioned awkwardly between Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan by some of the most arbitrary of the Soviet-era boundaries, there were ethnic riots in Uzbek regions in 1989. As elsewhere in the Soviet Union, ethnic violence was often fueled by local economic decline and competition for jobs and housing, sometimes exacerbated by the arrival of refugees from other regions. In 1990 there were even more violent riots in Osh, in Kyrgyz Ferghana, and also in Dushanbe, the capital of nearby Tajikistan.

But most Central Asian elites did not engage actively in the reform discussions of the perestroika era, and they shared the hostility to reform of the middle and lower levels of Soviet officialdom. Local populations shared their lack of enthusiasm. In the All-Union referendum on the maintenance of the Soviet Union organized in March 1991, over 90 percent of voters in the Central Asian republics voted to retain the Union.25

After independence, all Central Asian states rebuilt centralized political systems with strong Presidents, weak parliamentary systems, and regular but highly managed elections, systems similar in many ways to the former Soviet Union, in which the new nations had been incubated. Most of the new rulers continued to rely on networks forged within the nomenklatura, and on the highly personal clan networks developed in the late Soviet era, like the long-serving Central Asian leaders of the Brezhnev era. Four of the Central Asian polities – Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Azerbaijan – have proved remarkably stable and resilient. The personal nature of rule in all four states explains why they have often been caricatured as modern “Sultanates.” Centralizing trends also appeared in Kyrgyzstan, which seemed in the early 1990s to be moving towards radical democratic and market reform under Askar Akaev.

Culturally, the most important change in Central Asia was the revival of Islamic culture and traditions, which had been formally suppressed during much of the Soviet era, but flourished informally. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, new mosques and Muslim educational institutions opened. Increasing contacts with Afghanistan and the non-Soviet Muslim world allowed in new Muslim ideas and approaches, including more militant forms of Islam. In Kazakhstan, where Islamic traditions revived more slowly than in Uzbekistan or Tajikistan, there were 63 legal mosques in 1989, and 230 by 1991.26 All the new leaders in the region would align themselves to some degree with Muslim historical and cultural traditions, which they also incorporated within new forms of nationalism. New national myths and legends were constructed with considerable care and thought, in an attempt to turn the somewhat artificial “nations” of the Soviet era into modern nation-states that could inspire broad popular loyalty.

Saparmurat Niazov had been First Secretary of the Turkmen Communist Party since 1985. He was elected as President in 1990, became head of independent Turkmenistan in 1992, and ruled for 16 years before dying of a heart attack in 2006.27 He appointed himself President for life, built a cult of personality as florid as any in the modern era, assumed the title of “Turkmenbashi” or “Father of the Turkmen people,” erected golden statues of himself (one rotated constantly to face the sun), wrote himself into the national anthem, and even renamed the month of January after himself. He also tortured and imprisoned his opponents, and built a huge personal fortune derived largely from oil and natural gas revenues. The system he built proved remarkably stable, and when he died, power was inherited smoothly by Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, who continues to rule at the time of going to press (2017).

In Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov had also been a career communist. He was First Secretary of the Uzbek Communist Party from 1989, became the new President in 1990, and ruled until his death in 2016. After the August 1991 coup attempt in Moscow, which Karimov probably supported, the Uzbek Supreme Soviet declared that Uzbekistan had become the Independent Republic of Uzbekistan.28 In December 1991, Karimov was re-elected President. At the time, there still existed some independent political groupings including Birlik (Unity) and Islam Lashkari (Islamic forces).

The civil war in neighboring Tajikistan gave Karimov the justification he needed to concentrate power in his own hands. From January 1992 he personally appointed the Khokim, or regional governors of the 12 main regions. A December 1992 constitution extended the President's powers, and in December 1994, a new parliamentary body, the Oliy Majilis, replaced the former Supreme Soviet. Like Soviet parliamentary bodies, it meets rarely, and only to approve government laws. Karimov turned the Communist Party into the “People's Democratic Party,” and it became a firm supporter of the President's authority. He also launched a distinctive brand of nationalism focusing on the achievements both of former Soviet-era leaders of Uzbekistan, in particular Sharaf Rashidov, and on the exploits of Timur, whose statue replaced that of Karl Marx in central Tashkent.29

Together, these policies have produced a highly authoritarian regime hinged upon the almost unlimited powers of the president. President Karimov has made ruthless use of the security forces to crush opposition and the media are tightly controlled by the state. Beneath a thin veneer of democratic practices and institutions, political power is wielded in an indiscriminate and unchecked fashion.30

After Russia, Kazakhstan was the second largest of the Soviet republics, roughly the size of western Europe. It had significant resources in coal, metal ores (mainly in the north), and oil and gas (mainly in the west, on the shores of the Caspian Sea). It inherited a well-educated population with literacy rates of 98 percent, almost 60 percent of its population lived in towns, it had a large farmed area, and a modest industrial base. It was briefly a nuclear power, before agreeing in 1995 to give up its nuclear weapons in a deal brokered by the USA between Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan.

In Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbaev also made a smooth transition from Party First Secretary to President. He had been Prime Minister under Kunaev, then became First Secretary of the Kazakh Communist Party in 1989 after the removal of Gorbachev's controversial appointee, Gennadi Kolbin. Nazarbaev became President in 1990 and the former Supreme Soviet became the national parliament or majlis. In July 1990, Nazarbaev was elected a member of the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, as were Saparmurat Niazov and Islam Karimov. While using the democratic rhetoric of the perestroika era, and committed, like Gorbachev, to market reforms, Nazarbaev argued for what he called a “strong Presidential Republic,” on the grounds that a strong center would be needed during a period of difficult economic and political change. The first constitution of independent Kazakhstan, introduced at the end of 1992, reflected Nazarbaev's centralist approach.

Politically, Nazarbaev proved as conservative and as adept at managing parliamentary institutions as Niazov and Karimov. In 1993, conflicts emerged over the pace of economic reforms between the President and parliament, as in Russia. In October 1993, soon after the forced closure of the Russian Supreme Soviet, Nazarbaev dissolved the Kazakh parliament and called for new elections. When he failed to achieve a majority in 1994, the elections were declared null by the Constitutional Court. Nazarbaev ruled by decree until new elections gave him a majority in December 1995, and a referendum supported a new constitution that weakened the powers of the parliament and the judiciary. By 1997, Nazarbaev had taken over the one remaining independent newspaper, Karavan, and squeezed out the country's remaining independent radio and television stations by the simple expedient of demanding extraordinarily high license fees.31 From 1997 a reorganization of the provinces gave the center a stronger grip on its regions. In an attempt to consolidate the government's grip on the more Russified and urbanized northern parts of the country, Nazarbaev eventually moved the capital from Kazakhstan's largest city, Almaty, to Astana in the north-east. Formerly known as Akmolinsk when founded as a Russian fort in 1832, then as Tselinograd from 1960–1992, and Akmola from 1992–1998, the city was renamed once more as Astana, or “capital city,” in 1998. At the same time, Kazakh was made the national language, finally resolving long debates, similar to those in Ukraine, about whether the republic should be a federal or a unitary state.32

By the late 1990s, Kazakhstan, too, was a highly centralized presidential republic, dominated by the personal authority of the President and his family. As a 2009 essay puts it:

Now Kazakhstan has a political system centered around today's president and his family. His relatives and close, faithful lieutenants monopolize the key positions of the state. His elder daughter is chair of the Board of Directors of the chief Government TV channel. Her husband was chief of the Tax Police and deputy chair of the Committee on National Security. The president's second son-in-law has very entrenched interests in the oil business and officially holds the second highest position in the national oil company.33

Nazarbaev's main achievement has been to avoid serious ethnic conflict in a country which, at the time of independence, had more Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians (44 percent) than Kazakhs (40 percent) as well as other significant minority groups, including 5 percent of German ancestry.34 In 1990, Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote an essay arguing that northeastern Kazakhstan should become part of Russia, an idea that resonated with many Russians in Kazakhstan.35 Defusing such tensions complicated the task of developing a new Kazakh nationalism. The history of modern Ukraine suggests the care needed to manage such an ethnic balance, though in Central Asia as a whole, declining birth rates among the Slavic population and accelerating emigration since the 1980s eventually reduced the Slavic populations from about one third in the 1970s to about 15 percent today. The 1999 census confirmed that Kazakhs now constituted the majority of the republic's population.36

In foreign policy, Kazakhstan, like all the non-Russian PSIERs, has had to forge new international ties to replace Soviet-era links to Moscow. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan leased the Baikonur cosmodrome to Russia, and actively sought close economic links with Russia. Nazarbaev justified such ties with a rhetoric based on a pragmatic Kazakhstani version of “Eurasianism,” stressing the shared histories and traditions of Turks and Russians in Inner Eurasia.37 But Nazarbaev also built new economic and political ties, particularly with China and the USA, as Kazakhstan sought new ways of profiting from its resource wealth through a “multivector foreign policy.”

In Azerbaijan, Heidar Aliev, who had been the republic's leader between 1969 and 1982, became President in October 1993 after a chaotic interval dominated by violent internal conflicts and war with Armenia. Aliev created a strong, conservative regime that was inherited by his son, Liham Aliev, after Aliev's death in October 2003. Azerbaijan's politics has been dominated by the economics of fossil fuels. The discovery in the 1980s of large new reserves of oil, and the discovery of large reserves of natural gas in the 1990s, eased the task of building a new state, fueled a very fast economic recovery, and reduced pressure for either market reforms or democratic reforms.

In the more mountainous republics of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (mountains make up more than 90 percent of both countries), complex ethnic and regional divisions undermined attempts to build strong states. In both republics, there were long-standing divisions between Turkic-speaking Uzbeks and Persian-speaking Tajiks, while clan rivalries limited the power of the center. The other fault line that would drive wedges through the elite and between regions was that between Russified former communists, with limited sympathy for traditional forms of religion, and those regions, mostly in more rural or isolated areas, where Islam provided the dominant form of legitimation.

Of all the Soviet Central Asian republics, Tajikistan had the least favorable prospects as an independent territorial state. When created in 1929 from what had previously been an Autonomous Republic within Uzbekistan, it lost its two main cities, Bukhara and Samarkand, to Uzbekistan, along with 300,000 of Central Asia's 1.1 million Tajiks. The most significant ethnic divide is between Tajiks, whose language is a form of Persian, and Uzbeks, whose language is Turkic. Today, almost two thirds of the population is Tajik, but Uzbeks account for almost a quarter, most of them in Tajikistan's part of the Ferghana valley. Mountainous territories in the Pamir and Tienshan mountain ranges, and a long and porous border with Afghanistan, ensured the survival of particularly strong local, clan, and ethnic loyalties.38 The loss of subsidies from the Soviet federal government impoverished Tajikistan, and encouraged regional and tribal conflicts over the new state's limited resources. Lack of funds made it impossible to develop the country's modest reserves of gold, uranium, oil, and natural gas.

Tajikistan's first President, Rahmon Nabiev, had been the country's second to last communist First Secretary, but he lost power after the country disintegrated into a civil war that lasted from 1992–1997. Captured in September 1992, he was forced to resign as President. In November 1992, he was replaced by another long-time member of the Communist Party, the speaker of the Tajik Supreme Soviet, Emomali Rahmon (born Imomali Rahmonov). The civil war was fought initially between former communists and their Islamic opponents. But it was complicated and fueled by many other regional and clan conflicts. Russian and CIS troops were soon involved in the conflict, defending a government very like those that had emerged in the other Central Asian republics. Russia and Tajikistan's neighbors were particularly keen to police the border with Afghanistan in order to limit the spread of fundamentalist Islam.

By some estimates, the civil war may have caused as many as 100,000 deaths. It ended in 1997, when the UN helped negotiate a peace accord between the government and its pro-democratic and Islamic opponents, but sporadic violence persisted for a long time. In 1999, Rahmon was re-elected with a suspiciously high 96 percent of the vote. The collapse into civil war was a warning to all other republican elites, like the civil war in former Yugoslavia, of how fast power could unravel in new polities. To date (2017), Rahmon has survived in office for almost a quarter of a century.

Alone of the Central Asian republics, Kyrgyzstan gained independence under a leader who had not been a professional Communist Party official. Askar Akaev was a scientist, from the more Russified northern regions of Kyrgyzstan, who had lived for many years in Moscow, and had a genuine interest in democratic and market reforms. He was elected President in October 1991 after the elimination of two other candidates, both career politicians, who failed to gain majority support. Perhaps because of his long residence in Moscow, the heart of perestroika-era debates on reform, Akaev supported market reform and privatization, and took significant early steps towards political and economic reform. He also tried hard to prevent the emigration of the country's largely Russian intelligentsia. But economic decline and the 1993 constitution, which made Kyrgyz the country's state language, ensured that here, as in Kazakhstan, many Russians would leave.

For a while, it seemed as if a viable market-oriented democracy might emerge in Kyrgyzstan. In retrospect, it is clear that Akaev's goals were shared by only a minority within the Kyrgyz elite.39 And he himself lacked political experience and the political networks that might have allowed him to force through reform policies. Like Yeltsin in Russia, he faced opposition to his reform program from former communists within the Kyrgyz Communist Party, and felt obliged to revise the constitution to increase his own powers as President. But he failed to overcome regional differences within the elite, particularly between those from the Russified northern regions, which are divided by high mountains from the Turkic-speaking and more Islamic southern regions, and the Ferghana valley. In 2005, Akaev was overthrown during the so-called “Tulip” Revolution. His successor, Kurmanbek Bakiev, would fall in a similar revolution in 2010 to be succeeded by Central Asia's first woman president, Rosa Otunbayeva, who had been one of the leaders of the “Tulip Revolution.” Otunbayeva served as President only until 2011.

The failure of Akaev's attempts at reform, which were by far the most serious attempts in Central Asia, suggests the very real difficulty of introducing democratic market reforms under the conditions prevailing in post-Soviet Central Asia. In Central Asia, as in Russia, democratizing reforms weakened states, undermined their power to undertake decisive reforms, and created new ways of expressing underlying ethnic and political conflicts, while economic reforms generated widespread discontent.40

In much of Central Asia, the political challenge was not to create new political institutions, because most Soviet political institutions (with the exception of the Communist Party itself) continued to function, often under new names. More difficult was the task of creating new forms of loyalty and a new sense of legitimacy. Though many regions of Central Asia had historical traditions older than Russia itself, territorially organized states were a new phenomenon in the region, though in embryonic forms they had existed within the Soviet Union, and the Soviet practice of issuing national passports had begun to familiarize many with the new national identities. After 1991, all the new states found they would have to build new forms of legitimacy based on new national myths.

In both Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, whose titular ethnicities did not constitute a clear majority of society, rulers opted at first for “de-ethnicized” or multi-ethnic national identities. But eventually, even these states opted for single state languages. Building new national myths in a region of multiple, overlapping ethnic, historical, and cultural traditions turned out to be a complex process that created odd ambiguities and contradictions. Should Kazakh become the national language of Kazakhstan if almost half of the country was of Russian origin? Could Tajikistan claim the Samanid ruler, Ismail Samani, as a national hero, even if his capital in Bukhara and most of his former empire lay within Uzbekistan? Could the Turkmen claim ancient rights over their land if the historic Turkmen were in fact pastoralist invaders of the Middle Ages? And to what extent could the Soviet-era politicians who now ruled the post-Soviet republics reject the Soviet heritage?41 Easier to deal with were symbols of nationhood because these could be interpreted in many different ways. Turkmenistan has developed a new cult of the horse; Kyrgyzstan has built a cult around Lake Issyk Kul; cotton has become a symbol of Uzbek statehood; in Tajikistan, official nationalism is about mountains; in Kazakhstan it is about steppes.42

In Central Asia, for the most part, economic reforms have taken second place to nation building. Indeed, Nursultan Nazarbaev argued, in a textbook version of the “Chinese model” of reform, that it was important to give political reform priority over economic reform.43 And, to the surprise of some market reformers, it turned out, as we have seen, that strong states did not necessarily mean poor economic performance. In Central Asia, as in most of the other PSIERs, the two major predictors of recovery and eventual growth were, first, the creation of stable state structures and, second, the availability of exportable resources.

Initially, the breakup of the Soviet Union hurt all Central Asian economies by cutting long-established supply lines and removing Soviet-era subsidies. Railways, electricity networks, and pipelines had been built to link Central Asia to the Russian heartland, and they helped preserve many economic links even after independence. Kazakhstan's economy was particularly tightly bound to that of Russia. Most of Kazakhstan's industrial plants were under Moscow's control, and Kazakhstan had little understanding of their workings even months after independence. Nor was it always clear that the directors and largely Russian workforce of these plants would accept Kazakh government orders.

Kazakhstan sent 70 percent of its industrial production and mined products and 27 percent of its agricultural production to Russia. Russia received 100 percent of Kazakhstan's exports of iron ore, chrome ore, and aluminum; 95 percent of the republic's lead and phosphate fertilizer; 80 percent of its rolled metal, radio cables, aircraft wires, train bearings, tractors, and bulldozers; 75 percent of its cotton and silk; and 65 percent of its zinc and tin.

In return, most of Kazakhstan's imports of “cars, trucks, steel pipes, tires, lumber, paper, and most agricultural equipment” came from Russia.44 Loosening these ties was itself an economic revolution. In addition, Russia's 1992 economic reforms affected prices and markets throughout the former Soviet Union. The emigration of large numbers of Russians and Ukrainians from the region amounted to a significant brain drain. As in all the PSIERs, production fell sharply, poverty levels rose, and so did inequality and corruption.

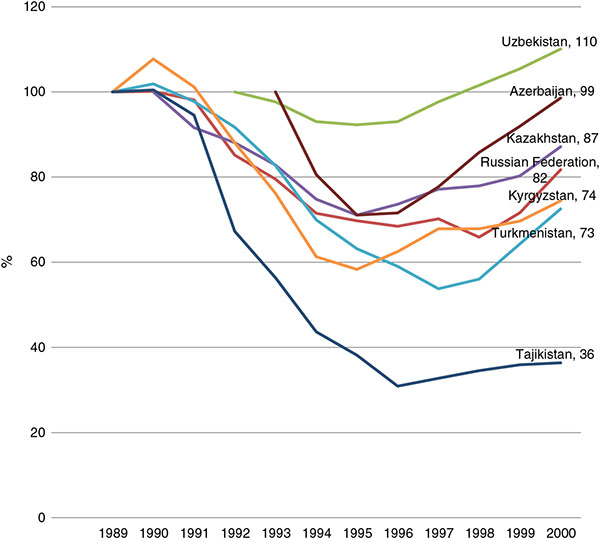

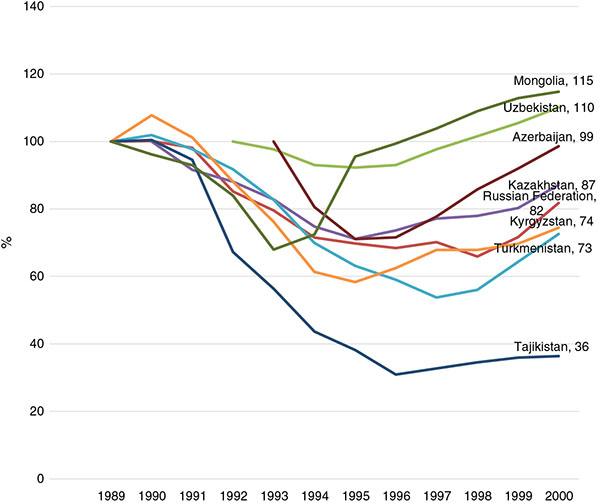

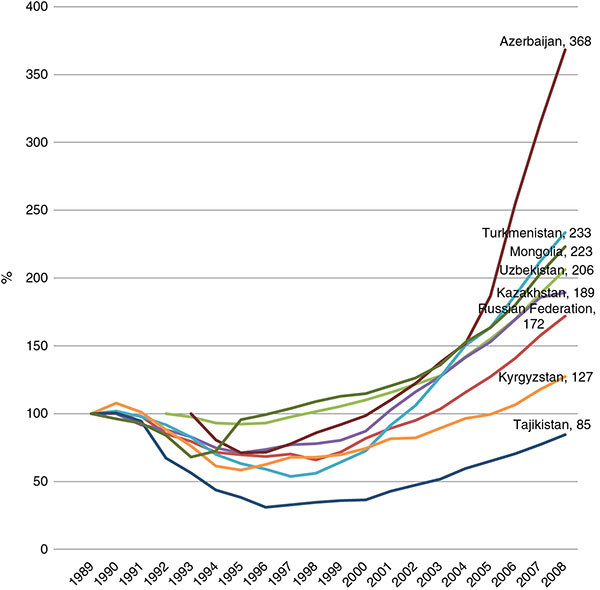

Most of Central Asia's new leaders showed limited interest in market reforms, except to the extent that they were forced on them by changes in the Russian republic. In Uzbekistan, Karimov resisted market reforms by capping prices and maintaining subsidies on many basic products. By 1993, according to World Bank estimates, subsidies and credits to enterprises in Uzbekistan amounted to 21 percent of GDP.45 (On levels of privatization, see Figure 18.2.) Since then, levels of privatization have risen to about 45 percent of GDP, and many subsidies have been reduced, but many prices are still controlled and most farming is still managed by collective or state farms. In Turkmenistan, Niazov maintained an even higher level of state control and maintained subsidies to major state enterprises. In 2005, only 25 percent of Turkmenistan's GDP had been privatized. Yet neither economy collapsed, and Uzbekistan, in particular, maintained higher levels of output than most PSIERs, and kept earning significant revenues from cotton exports. In Turkmenistan, output fell to about 60 percent of the 1989 level, but then recovered fast, buoyed by exports of oil and gas. Autocratic rule in both countries maintained greater institutional continuity than in Russia, and, though levels of corruption remain high, the state itself retained control over most forms of large-scale rent-seeking. By 2008, per capita GNI in both Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan was double the level for 1989 (Figures 19.3 and 19.4).

Figure 19.3 Changing GNI of Central Asian republics, 1989–2000 as % of 1989 level. Based on Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, 333, from World Bank figures. With permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Figure 19.4 Changing GNI of Central Asian republics, 1989–2008 as % of 1989 level. Based on Myant and Drahokoupil, Transition Economies, 333, from World Bank figures. With permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Economically, Nazarbaev was close to Gorbachev and that may be why he committed earlier and faster than most other Central Asian leaders to economic reforms. In 1992, most wholesale and retail prices were liberalized and privatization began, but the government retained control over exports. A second round of privatization began in 1993, using vouchers. Agriculture and livestock farming were privatized under laws passed in 1995. A serious economic crisis in 1996 led to a new round of privatization. The government also began to privatize larger enterprises, many of which were sold to foreign companies. By 1997, Kazakhstan was attracting more foreign investment than any of the other PSIERs.46 But market reforms would stall at this stage, when about 65 percent of the Kazakh economy was being generated from the private sector, a level similar to that of Russia. As in other resource-rich PSIERs, increasing revenues from oil and natural gas reduced the pressure for further market reforms. However, as in Turkmenistan and Russia itself, Kazakhstan's overall economic performance has been impressive, particularly since the increase in oil prices at the end of the 1990s. By 2008 Kazakhstan's GNI per capita was almost double the level in 1989.

More than 20 years after the Soviet Union fell apart, it is clear that the Central Asian economies that recovered least well were those of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. In both, total production still hovers around the levels for 1989. Weak governments slowed recovery in both states. In Kyrgyzstan, ethnic and regional tensions have created political instability, which ensured political and economic drift after aggressive early attempts at economic reform. In Tajikistan, civil war and the loss of Soviet subsidies in what was already the poorest of the Soviet Central Asian republics help explain why the economic decline was more severe than in any of the other PSIERs, and the recovery was slower. In 2002, 80 percent of the Tajik population lived below the poverty line.47 Market reforms have been ad hoc and limited; in 2007, less that 60 percent of the Tajik economy was in private hands, and most large enterprises and collective reforms are still managed by the government. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, Tajikistan has achieved some political stability. But it remains impoverished and autocratic, and economic reforms have made little impact, while the government lacks the funds needed to develop the country's significant resource wealth.

In Central Asia, as in most post-Soviet republics, there turned out to be no simple correlation between democratization and economic growth. In the 1990s, Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan, at opposite ends on the scale of privatization, both suffered declines in output below 70 percent, and a slow recovery. The Central Asian societies whose economies recovered best were those with strong governments and exportable resources: Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan.

XINJIANG

Xinjiang shared many historical, cultural, and geographical similarities with the formerly Soviet regions of Central Asia. Its north shared many cultural and geographical features with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, and its southern regions, in the Tarim basin, had much in common with Transoxiana. But, after a chaotic period of independence in the first half of the twentieth century, in the second half of the century its history was shaped overwhelmingly by decisions taken in Beijing. Real modernization began here only with the modernizing reforms of Deng Xiaoping, and Xinjiang did not really enter the fossil fuels era until the 1990s.48 Its modernization had been delayed, like that of much of China, during the chaotic years of Mao's rule. In the late 1970s, Xinjiang was barely any wealthier or more modernized than in 1950.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 helped accelerate economic growth by ending Xinjiang's status as a fortified border region. Xinjiang's western borders began to open in the 1980s. In 1983, trucks were allowed to enter Kazakhstan through the Ili valley and in 1987 the new Karakoram highway linked Kashgar to Pakistan, while in 1990, a new rail line was completed between Urumqi and Almaty. After 1990, border trade increased rapidly. Most of the cross-border trade was controlled by the Xinjiang government, but increasing numbers of Uighur also engaged in private trade both abroad and in China itself, creating the beginnings of a new Uighur middle class. The region's railway network was finally developed; only in 1999 was Kashgar linked by rail to China. Between 1993 and 1995 the Taklamakan Desert Highway was built, running north–south through the Taklamakan desert. With massive inputs of water and fertilizers, cotton production increased by almost 30 times between 1978 and 1998, while the acreage under cotton doubled.49

By the 1990s, Xinjiang was also producing significant amounts of fossil fuel energy. Prospecting for oil had begun as early as the 1890s, but serious extraction began in the 1940s, in the era of Sheng Shicai, with the help of Soviet technicians. The major Karamay (“black oil”) field in northern Zungharia was opened in 1955. Xinjiang also produces natural gas, which is now piped to China. Given China's limited supplies of oil and gas, and the vulnerability of shipments of Middle Eastern oil, which pass through the straits of Malacca, such domestic sources are extremely important to China, which has been willing to pay high prices to develop them. But though economic development in Xinjiang has been rapid, foreign investment has been limited, and in 2004, 80 percent of the region's industry was still state-owned. So, as in the eighteenth century, Xinjiang is still a drain on the budget of the Chinese heartland; by some estimates it costs 20 percent more than it earns.50 Although China clearly controls Xinjiang in its own interests, modern Xinjiang also benefits from massive Chinese subsidies.

Much Chinese investment has been in support of increased production of raw materials and energy. Massive irrigation projects and the building of new canals and karez, or underground water channels, have increased the area being farmed to 3.4 million hectares. But here, as in Soviet Central Asia, over-irrigation is causing ecological damage and approaching the limits of what is available from rivers that originate from glaciers in the region's high mountains. The Tarim river now barely reaches its former terminus in Lop Nor, desertification is increasing as the water table is drawn down, and many of Turfan's karez are no longer functioning.51

Xinjiang has finally begun to look modern and to develop a modern consumerist culture. Bicycles, washing machines, and TVs have appeared even in rural areas. Living standards are highest in the more urbanized Han-dominated regions of Zungharia. The Tarim basin, 95 percent of whose population is Uighur, has a per capita income half that of Xinjiang as a whole.52 Zungharia, like Kazakhstan, has attracted large numbers of migrants from the imperial heartland, but in Xinjiang, that migration is continuing, while in Transoxiana it has ceased. In Zungharia, Han migration is beginning to swamp the indigenous population. In 1947, Han and Hui made up about 5 percent of the population of Xinjiang and the Uighur 75 percent; by 2000, Han and Hui made up more than 40 percent of the population, which was almost as large a proportion as the Uighur.53 Most of the Han and Hui populations have settled in the north, but increasing numbers are settling in the Tarim basin, many of them in segregated apartment complexes.

Their separateness highlights the fact that Chinese attempts to reduce the region's cultural distinctiveness have failed as decisively as Soviet attempts in Soviet Central Asia. The tenacious survival of Muslim traditions, increasing education, travel by local merchants and intellectuals, and increasing contact with the independent republics of Central Asia have all generated new forms of nationalism among the non-Han populations in Xinjiang. These, in turn, have provoked a backlash in Chinese policy, which has returned since the late 1990s to less tolerant cultural policies in the region. All the preconditions now exist for the emergence of a strong independence movement in Xinjiang, and since the 1990s there have been several terrorist incidents in the region, and many signs of increasing inter-ethnic tension. But so far, a combination of Chinese government repression and improving living standards in Xinjiang have prevented that movement from taking highly organized forms.

Alone among the large non-heartland regions of Inner Eurasia, Xinjiang remains a colony in the traditional sense, and the example of independent neighboring states will surely encourage some form of separatism. But, like Soviet Central Asian states in the late Soviet period, rapid economic growth and a continuation of subsidies from the heartland may reduce the pressure to break away from the Chinese Empire and allow forms of accommodation short of full independence. In fact, one way of interpreting recent events in Xinjiang is as evidence of an expanding Chinese informal empire. So rapid is the growth in Chinese economic power and influence that China is developing the beginnings of an informal empire in Central Asia, where Chinese armies with imperial aspirations first arrived in the first century BCE.

In 1996, China initiated the meetings that led to the formation of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization or SCO. Intended originally to deal with possible border conflicts, the meeting also took up the common problem of Islamic extremism. Since then, Central Asian republics have ended the training of Uighur militants on their territory and even handed over suspect militants to China. In 2001, after attempts on the life of the Uzbek President Islam Karimov, Uzbekistan joined the SCO. Intentionally or not, this organization has become a powerful source of Chinese influence in Central Asia. In combination with Chinese commercial projects such as the Kazakh/China oil pipeline first agreed to in 1997, the SCO represents “the greatest extension of Chinese power into Central Asia beyond the Pamirs since the Tang period.”54 As China becomes an increasingly important market for Mongolian produce, too, it is clear that, while Russian imperialism in Inner Eurasia is on the retreat, Chinese quasi-imperialism in the region is advancing. By 2010, China was probably investing as much in Central Asia as Russia. But the “quasi” makes all the difference. Beyond China's current borders, its imperialism depends on modern, market-dominated forms of mobilization rather than on the more direct forms of mobilization that dominated the era before fossil fuels.

MONGOLIA, 1985–2000: REFORM AND INDEPENDENCE

Mongolia's history in the 1990s is peculiarly interesting because it was the only PSIER in which a highly marketized economy evolved in the 1990s, along with relatively democratic political structures. Mongolia's history suggests that, under slightly different circumstances, many of the other PSIERs might also have evolved along similar lines. What made the difference?

Curiously, Mongolia's history in the 1990s is in some ways more similar to that of eastern Europe than to the other PSIERs. Like many East European countries, Mongolia already had a strong sense of national identity, many Mongolians welcomed the prospect of independence and reform, and there was considerable elite turnover. As in eastern Europe and the Russian heartland, serious discussion about reform began during the era of perestroika, and involved many educated Mongolians who were not strictly part of the political elite. Finally, Mongolia's economy had been less tightly integrated into that of the Soviet Union, so that it was easier for Mongolia than for most other PSIERs to seek new sources of financial and technical aid from international aid agencies and countries outside the former Soviet Union.

Unlike most of the other PSIERs, Mongolia also experienced something of the ferment of debate that Russia experienced during the years of perestroika. In Mongolia, as in Russia, serious reform began after the removal of a former leader, Tsedenbal, in August 1984. With Soviet agreement, he was sacked on “medical grounds” while in the Soviet Union for medical treatment. His replacement, Jambyn Batmonkh, was not a Party apparatchik but the Rector of the Mongolian State University. In the late 1980s, Batmonkh committed to a Mongolian version of perestroika. He allowed some decentralization in economic decision making and a small increase in private livestock holdings. Perestroika (öörchlön shinechlel) was accompanied by glasnost’ (il tod). In 1988, newspapers began to criticize the command economy. In 1990, an essay by Batbayar (pseudonym “Baabar”), called “Don't forget! If you forget you perish,” criticized Soviet rule over Mongolia in general.55 The author had been educated in Poland, and his work reflected the dissident ideas circulating among Soviet and eastern European intellectuals. As in the Soviet republics and eastern Europe, nationalist sentiments re-emerged in public debate. One critic asked why Mongolian studies were better developed in the West or the Soviet Union than in Mongolia itself.56 In 1988, proposals surfaced for multi-party elections and in 1989 a commission was set up to examine the purge era.

By 1990, it was already clear that many economic and technical ties with Moscow would be cut, and this would hurt Mongolia. Mongolia lost Soviet military protection and Soviet subsidies which, by some estimates, accounted for 30 percent of Mongolian GDP.57 It lost Soviet investment and technical services, which were crucial to manufacturing and energy production, as well as subsidized supplies of oil and electricity, and large markets for meat and livestock produce. It also had to start paying in hard currency for Soviet imports. Inevitably, Mongolia began to seek other allies, and to look for new forms of financial and technological support.

The first major internal changes came in 1990. In Mongolia, unlike most of the other PSIERs, but like many countries in eastern Europe, reform was initiated by pressure from below the government elites. Pro-democracy demonstrations had begun on Ulaanbaatar's massive Sukhebator square in December 1989, as the Soviet Empire in eastern Europe was collapsing. They were led by members of Mongolia's small intelligentsia, many of them educated in the Soviet Union or eastern Europe, and most with close ties to Mongolia's ruling elites. Teachers and students from the Mongolian National University played a crucial role. Large demonstrations were organized on December 10, International Human Rights Day, with goals and slogans borrowed from the ferment of ideas that had emerged in the 1980s among Soviet intellectuals. Typical of the leaders of the reform movement was Sanjaasürengiin Zorig, a lecturer at the National University, of Russian and Buriat parentage, who had graduated from Moscow State University, knew the ideas of dissident Soviet intellectuals, and was deeply committed to non-violent protest.58 Demonstrators took up many of the core demands of the perestroika reforms. They demanded an end to one-party rule, increased respect for human rights, new elections, a free press, honest study of Mongolia's Soviet-era history, and the development of a socialist market.59 A Mongolian rock band, “Bell,” played at the demonstrations.

Government leaders were divided on how to react. The Tiananmen massacre just six months earlier, in June 1989, had shown the possibility and the dangers of violent repression, while the collapse of eastern European socialist governments at the end of 1989 showed that the Mongolian leadership could expect little support from Moscow if they used force. Demonstrations continued through the cold winter and spring, and an independent paper appeared, the first since 1921. In February 1990, demonstrators tore down a statue of Stalin in front of the State Library. On March 7, 10 leaders of the reform movement put on traditional robes and began a hunger strike in Sukhebator square, where the temperature was −15°. The gesture attracted large crowds of supporters. Workers at the Erdenet and Darhan factories went on strike and monks from the Gandan monastery joined the demonstrations. On March 9, having been advised by the Soviet government to negotiate with reformers, the Politburo agreed to resign and hold broadly based elections to the parliament, the “Great Khural,” after 70 years of single-party rule.60 Batmonkh was replaced as Party leader by Punsalmaagiin Ochirbat.