PREFACE: THE IDEA OF INNER EURASIA

THE ARGUMENT: CENTRAL THEMES

This volume covers a vast area – the central, or “Inner” half of Eurasia – and more than 750 years of that region's history. Writing at this scale, it is easy to overlook the contingent events, the pathways not taken. So, though my central argument is about sustained ecological and geographical pressures that shaped the region's history in enduring ways, I have tried not to ignore the alternative histories and might-have-beens – Lenin falling under a tram in September 1917, or a Lithuanian conquest of Muscovy, or a revived Mongolian Empire in the sixteenth century.

Contingencies have shaped the writing as well as the argument of this book. In April 2016, I was in London, working in the British Library on footnotes, formatting, transliterations, and the many other obsessive details involved in finishing a manuscript, when I picked up a Russian-language newspaper, Pul's UK, “Pulse UK.” Its front page advertised an article on “Yurta v Khaigaite,” “A Yurt in Highgate.” For an English-trained historian who lives in Australia, the phrase reeked of globalization. But it also captured something of the project I have been working on for more than two decades: a history of Inner Eurasia, a huge region whose two historical poles in the last millennium have been Mongolia and Russia. Finding a free Russian-language newspaper in London also reminded me how much more globalized today's world is than the world I grew up in, or even the world in which I began this project. (I was reminded recently that I signed a contract for this project in 1991, the year the Soviet Union broke up; that was before any of the events described in this book's last two chapters.) Later that day, I had a beer in a nearby pub, “The Rocket.” That was a serendipitous reminder of a second major theme of this volume: the fossil fuels revolution (of which steam engines were a major early component) and the way it has transformed our world, including, in rather distinctive ways, the world of Inner Eurasia.

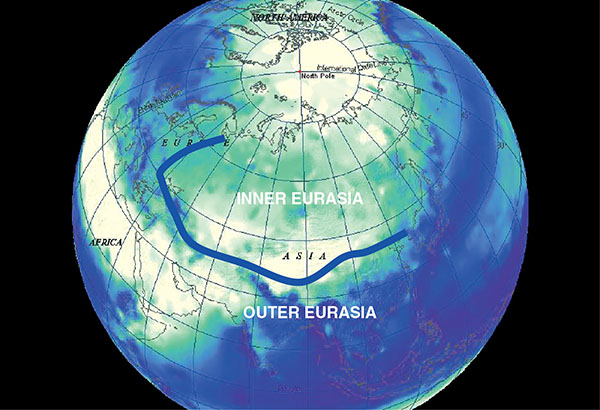

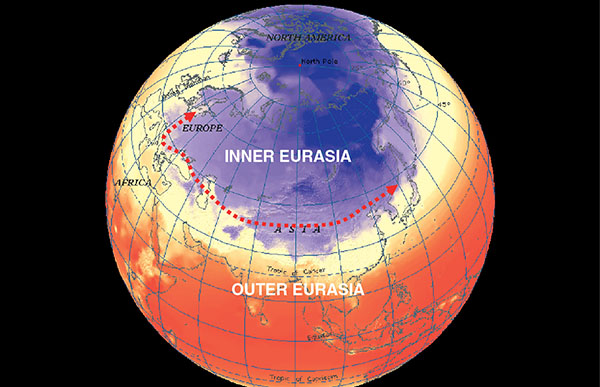

The first volume of this history appeared in 1998.1 Taken together, the two volumes tell the story of a distinctive world region that includes all of the former Soviet Union, as well as Mongolia and Chinese Xinjiang. It includes all of the inner, more northerly, more arid half of the Eurasian land mass. Inner Eurasia's complement is “Outer Eurasia.” Outer Eurasia includes China, South-East Asia, the Indian sub-continent, Persia, and Europe (Map 0.1). Outer Eurasia has been the subject of much more historical scholarship because it had much larger populations, more cities, and more complex societies that generated abundant historical records. To study the history of Inner Eurasia, therefore, is to study regions that have been relatively neglected by traditional synoptic historiography.

Map 0.1 Inner and Outer Eurasia. Adapted from Encarta.

The first volume of this history began when human (or human-like creatures) first entered Inner Eurasia, over 100,000 years ago. It ended in the thirteenth century with the rise of the Mongol Empire, the first empire to dominate most of Inner Eurasia. The second volume describes Inner Eurasia in a more inter-connected era, in which its many different communities and polities were shaped by influences from all of Eurasia and eventually from the entire world.

This volume begins with the breakup of the Mongol Empire after 1260, and the creation of regional khanates. Then it tracks the decline of pastoral nomadic polities, and the rise of a second Inner Eurasian empire, based on agriculture rather than on pastoral nomadism. That empire began as Muscovy and became Russia. It arose in the forested lands north-west of the Urals. By the late nineteenth century, it ruled most of Inner Eurasia. But the world was changing around it, in an era of global competition and fossil fuels. Struggling to cope with these changes, the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917. It was speedily rebuilt in a new form, that of the Soviet command economy. By 1950, the Soviet Union not only dominated Inner Eurasia, as the Mongol and Russian empires had done before it, it had also become a global superpower. In 1991, like the Mongol Empire in 1260, the Soviet Union also collapsed while still a superpower. In its place, there emerged new, independent polities, all struggling to find a place in a globalized, capitalist world.

These volumes cover so much history that their approach has to be synoptic. They rest mainly on the work of other historians rather than on exhaustive primary research. One advantage of synoptic histories is that they will generally be more accessible to non-specialists. But, like gambits in chess, they begin with a sacrifice: they give up the expert's accumulated knowledge of particular, sharply focused topics, because this type of expertise is unattainable at very large scales. So synoptic histories may miss details or nuances that specialists will regard as important. But the point of a sacrifice is to see the game in new ways that offer new strategic perspectives and insights. (Of course, the aficionado of gambits will also argue that conventional strategies are gambits, too, because they sacrifice the possibility of unexpected insights and limit your view of the game.)

The main new insight we gain by reframing the history of this region is an appreciation of some important and distinctive features shared by all Inner Eurasian societies. In her wonderful history of the medieval world system, Janet Abu-Lughod argues that new insights often arise not just from new research and new facts, but also from “changing the distance from which ‘facts’ are observed and thereby changing the scale of what falls within the purview.”2 If a shift in the light can change what a photographer sees, so, too, a shift in the concepts we use to illuminate the past can change what we see as historians, sometimes in subtle ways, sometimes in more profound ways.

A single large question shapes the argument of both volumes: how has Inner Eurasia's distinctive ecology and geography shaped its history? In particular, how have geography and ecology shaped patterns of state building and resource gathering, or patterns of “mobilization.” In exploring these patterns, the argument builds on two central ideas: the geographical concept of Inner Eurasia, and the historical concept of mobilization. Both require explanation.

INNER EURASIA

The idea of Inner Eurasia was introduced and defined in Volume 1, where I argued that there is an ecological and geographical coherence to this entire region that has shaped its political and cultural history over many millennia, and continues to do so today. This section will summarize those arguments.3

Inner Eurasia includes the inner and northern half of the Eurasian landmass. At about 27 million sq. kilometers, Inner Eurasia is similar in size to its complement, Outer Eurasia. But it is distinctive enough to deserve its own history. Of course, such claims must not be overstated. Not everything changes at the imaginary border between Inner and Outer Eurasia. Nevertheless, particularly at large scales, the differences are important and durable enough to have generated distinctive histories. Focusing on how geography and ecology shaped Inner Eurasia's history can help us move beyond nationalistic accounts of the past that smuggle in essentially metaphysical assumptions about the distinctiveness of particular peoples, nations, or ethnicities. By making this move, nationalist historiographies often assume what needs to be explained. They also run the risk of anachronism. Was there really a distinct “Russian” people in the thirteenth century? Modern Ukrainian nationalists would certainly deny such a claim. Were the Mongols of the thirteenth century really the same “people” as today's Mongols? Did the Uzbek and Kazakh “nations” first appear in the fifteenth century?

Focusing on geography rather than ethnicity can, of course, generate new forms of “essentialism.” The danger is apparent in modern “Eurasianist” writings, which also find an underlying coherence in the histories of all the lands once within the Russian and Soviet empires.4 The argument of this book overlaps at some points with Eurasianist approaches to the history of Inner Eurasia, but it also differs from them in important ways. Above all, its approach is scholarly, tentative, and exploratory. It tries to identify some ways in which durable aspects of Inner Eurasia's geography and ecology may have shaped the histories of Inner Eurasian societies and polities, without overstating the region's coherence or understating the role of contingency and the unexpected.

At very large scales, three large features of Inner Eurasian geography have influenced its history. Inner Eurasia differs from Outer Eurasia ecologically, demographically, and topographically.

Ecologically, Inner Eurasia is generally less productive than Outer Eurasia. Interiority means that most of it receives less rainfall because it is far from the oceans, and its long, northern Arctic shores are ice-bound for much of the year (Map 0.2). Remoteness from ice-free oceans also ensures that Inner Eurasian climates are generally more extreme, more “continental,” than those of Outer Eurasia because they are not moderated to the same extent by large bodies of open water. Inner Eurasia is also more northerly than most of Outer Eurasia, so that its climates are generally colder, and it receives less sunlight for photosynthesis (Map 0.3).

Map 0.2 Interiority and low rainfall. Interiority means generally lower rainfall than in Outer Eurasia. Darker shading = higher rainfall. Adapted from Encarta.

Map 0.3 Northerliness and low agricultural productivity. Northerliness means lower temperatures, less sunlight, and generally less photosynthesis than in Outer Eurasia. Darker regions inside the dotted line have average January temperatures below 0°. Adapted from Encarta.

Inner Eurasia's distinctive ecology helps explain a second distinctive feature: its demography. Aridity, lack of sunlight, and continental climates explain why it took so long for agriculture to get going in most of Inner Eurasia, while it flourished in much of Outer Eurasia. In Inner Eurasia, there were a few regions of early agriculture along China's northern and northwestern borders, in small irrigated oases in Central Asia, and in regions of rainfall agriculture north of the Black Sea. But then it stalled, so agriculture was a late arrival in most of Inner Eurasia. That meant that, for much of the agrarian era of human history, when agriculture provided the people and resources for wealthy states and empires, Inner Eurasia remained a region of low productivity and thin populations. Only from about 1,500 years ago, when large numbers of peasants began migrating from eastern Europe into the forested lands west of the Urals, did rainfall agriculture start to spread more rapidly through Inner Eurasia. As agriculture spread, populations increased, and so did the number of villages, towns, and cities. Nevertheless, the large differences persisted. The late arrival of agriculture meant that Inner Eurasian societies had access to less energy and less food than most societies of Outer Eurasia, so they were (and they remain) more thinly settled than most Outer Eurasian societies (Map 0.4).

Map 0.4 Generally lower agricultural productivity than Outer Eurasia means low population density, even today. Darker regions have denser populations. Adapted from Encarta.

For several millennia, the dominant productive technology of Inner Eurasia was pastoral nomadism, a lifeway that depended primarily on domesticated animals rather than domesticated plants. Herding horses, sheep, and cattle worked well in the arid steppelands that cross the southern half of Inner Eurasia like a belt. But if you rely on animals rather than plants, you live higher on the food chain than farmers, and that means less energy is available because so much energy is lost as it moves from photosynthesizing plants to herbivores and up through the food chain. This is why the food chain generates a sort of ecological pyramid, with smaller populations the higher you climb. Just as you find fewer lions than zebra in a given area of savanna, so, too, you find fewer pastoral nomads than farmers for a given area of land. Indeed, ecologists often argue that so much energy is lost as it moves up the food chain that populations decline by approximately 90 percent at each step. This means there is a neat ecological logic to the fact that Inner Eurasian populations were usually between one tenth and one twentieth the size of Outer Eurasian populations, even though the two regions are about the same size (Table 0.1 and Figure 0.1).5 Demographic statistics highlight the fundamental contrast in productivity between the two halves of the Eurasian landmass.

Table 0.1 Populations of Inner and Outer Eurasia

| Date | Inner Eurasia pop. (mill.) | Outer Eurasia pop. (mill.) | Ratio (%): Inner/Outer Eurasia |

| −200 | 4 | 105 | 4 |

| 0 | 5 | 143 | 4 |

| 200 | 6 | 162 | 4 |

| 400 | 7 | 157 | 5 |

| 600 | 8 | 161 | 5 |

| 800 | 9 | 178 | 5 |

| 1000 | 10 | 215 | 4 |

| 1100 | 12 | 268 | 5 |

| 1200 | 16 | 301 | 5 |

| 1300 | 17 | 301 | 6 |

| 1400 | 17 | 287 | 6 |

| 1500 | 20 | 353 | 6 |

| 1600 | 24 | 466 | 5 |

| 1700 | 30 | 525 | 6 |

| 1800 | 49 | 792 | 6 |

| 1900 | 129 | 1,331 | 10 |

| 2000 | 340 | 4,050 | 8 |

Source: McEvedy and Jones, Atlas of World Population History, 78–82, 158–165.

Figure 0.1 Populations of Inner and Outer Eurasia: same area, different demography. Data from McEvedy and Jones, Atlas of World Population History, 78–82, 158–165.

Low population density shaped Inner Eurasia's political, economic, and social history. Above all, it meant that people (and the stores of energy that they represented) were scarcer and more valuable relative to land than in Outer Eurasia. This is why political systems in Inner Eurasia often seemed more interested in mobilizing people than in controlling land.

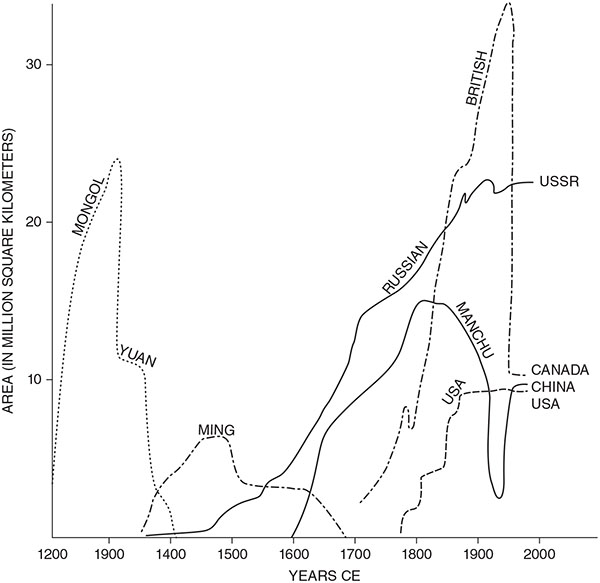

The third distinctive feature of Inner Eurasia is its topography. Dominating Inner Eurasia is the largest area of flatlands in the world, a feature that aided the movements of pastoralists, merchants, and armies, and deprived cities and states of natural defenses. Successful and mobile armies could advance over huge distances without facing major geographical barriers. This is one reason why Inner Eurasia was home to the largest contiguous empires that have ever existed: the Mongol, Russian, and Soviet empires (Figure 0.2). On the other hand, the ecology and sheer size of the vast Inner Eurasian flatlands posed distinctive challenges to armies unused to them. As the Persian emperor Darius discovered in the sixth century BCE, the Han emperor Wudi in the first century BCE, and Napoleon and Hitler in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, moving infantry armies through the vast, arid plains of Inner Eurasia could be a costly, dangerous, and thankless task.

Figure 0.2 Largest world empires. Taagepera, “Overview of the Growth of the Russian Empire,” 5.

MOBILIZATION

The second idea that needs some explanation is that of “mobilization.” Mobilization means gathering resources, whether in the form of labor, energy, or materials.

All complex systems mobilize energy and resources, from stars to plants to political systems. They all depend on flows of energy, and understanding how they capture and use energy can help us understand how complex systems work.6 The biosphere traps energy from sunlight through photosynthesis; humans tap those flows of energy to feed and support themselves; and states mobilize energy and resources from the populations and lands they rule. In effect, the appearance of states in the last five thousand years of human history has added a new step to the food chain as elites mobilized energy from other humans who mobilized it from other organisms.

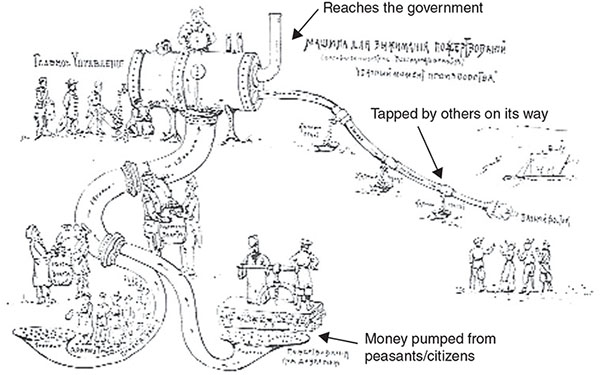

The illustration in Figure 0.3 is from the early twentieth century. In cartoon fashion, it captures the idea of mobilization nicely, as resources generated by the population are squeezed out of them, pumped to the government, and occasionally siphoned off by intermediate groups of what a modern economist might call “rent-takers.” The sixteenth-century Muscovite notion of “kormlenie” – literally the right of officials to “feed” off the population – captures perfectly the idea of mobilization as an extension of the food chain. In the 1990s the same word was used to describe the pillaging of state property that took place after the breakup of the Soviet Union.7

Figure 0.3 A mobilization pump, from a Red Cross cartoon produced during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. Money to support wounded soldiers is squeezed from the peasantry and accepted in the form of donations; that money is tapped legally and illegally as it is piped to the government, various sections of which take significant shares of it, before the reduced flow travels through Siberia, where more is tapped, leaving very little at the end for wounded soldiers. Christian, “Living Water,” 4. Reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press.

We can learn a lot about states by studying exactly how they mobilized resources. Inevitably, their methods depended on the environments in which they emerged, and the methods their subjects used to mobilize food, energy, and supplies. In Inner Eurasia, limited resources, scattered populations, and vast distances explain why mobilizing was generally harder than in Outer Eurasia, and would require different strategies. These strategies would shape the political cultures of the entire region, which is why the idea of mobilization will play a strategic role in the argument of this volume.

Mobilizing the energy, products, and military power of pastoral nomads was a very different task from that of mobilizing energy, resources, and military power from peasant farmers. Mobilizing resources from peasants was also a trickier challenge in regions such as Inner Eurasia, where agricultural productivity was low, than in more productive regions. In Inner Eurasia, would-be mobilizers had to muster resources over large areas, and that required high levels of elite mobility and coordination. Competition between rival mobilizers increased the importance of mobility and coordination over large areas, creating sustained pressure to build highly centralized mobilizational machines with enormous reach. We will see later the many ways in which such pressures shaped methods of mobilization and state formation in Inner Eurasia over many centuries, creating centralized and disciplined political cultures whose habits still shape the region's history today. In Inner Eurasia, direct mobilization of resources through the effective threat of state coercion was generally more important than mobilization through commercial exchanges. Direct mobilization is sometimes described as “tribute-taking.”8

In the last two centuries, however, the fossil fuels revolution and the growth of commerce have transformed strategies of mobilization everywhere, and these changes would pose new challenges to Inner Eurasian societies.

On the one hand, Inner Eurasia, which had seemed ecologically impoverished in the agrarian era of human history, suddenly began to look more prosperous in an era that drew power and wealth from fossil fuels and mineral ores, both of which Inner Eurasia had in abundance. In this sense, Inner Eurasia was a beneficiary of the fossil fuels revolution.

On the other hand, fossil fuels technologies relied much more than traditional technologies on efficiency and technological innovation. So they worked best with more commercial strategies of mobilization that encouraged innovation and efficiency and relied more on market forces. As markets became global from the sixteenth century, and new opportunities for arbitrage on a global scale generated increasing flows of wealth, strategies of commercial mobilization became increasingly powerful. There emerged city-states, and eventually whole societies, such as the Netherlands and the UK, whose wealth came largely from commercial mobilization. These are the societies that Marx described as “capitalist.” Their great advantage was that mobilizing through markets encouraged more creative and effective use of energy and resources than more coercive forms of mobilization, because entrepreneurs had to economize in order to undercut rivals and make profits. So commercial mobilization could generally make energy and resources go further than traditional strategies of direct mobilization.

The new technologies of the fossil fuels era emerged in western Europe, within societies that relied increasingly on commercial mobilization. And they posed difficult problems for the mobilizational strategies of the societies that dominated Inner Eurasia by the nineteenth century. Could they survive into the modern era while relying on traditional strategies of direct mobilization to mobilize Inner Eurasia's vast reserves of fossil fuels and mineral ores? Or would they have to go through the painful process of renovating their traditional mobilizational strategies in order to unleash the power of market forces? Much of the history of Inner Eurasia in the fossil fuels era would be shaped by these tensions.

The fossil fuels revolution will divide this book in half, because we will see that, though it was possible to enter the fossil fuels era using traditional strategies of direct mobilization, and Inner Eurasia's vast resource wealth, it was hard to stay the course without also unleashing the power of the market. In Inner Eurasia, that difference greatly complicated the task of entering the modern era.

MOBILIZATION IN INNER EURASIA

The core argument of this volume, then, is that the geography and ecology of Inner Eurasia created durable pressures that shaped structures of mobilization over many centuries and remain significant today. Those structures depended mainly on direct mobilization of resources over large areas by highly centralized, disciplined elite groups with great reach. Market forces played a more limited role in mobilization, which created a persistent bias towards extensive rather than intensive forms of growth. But it is important to stress that this is not a deterministic argument. We will note many points at which the histories of different parts of Inner Eurasia might have taken different pathways. It is not hard to imagine alternative pathways into and out of the revolutionary crisis of 1917, or to imagine a powerful Lithuanian empire dominating fourteenth-century Muscovy, or to see different, and perhaps less centralist outcomes to the breakdown of the Soviet era. Nevertheless, I will argue that the ecology and geography of Inner Eurasia created sustained pressures that made the emergence of centralist patterns of rule and economic management particularly likely. And I will also argue that it was vanishingly unlikely that powerful pastoral nomadic polities would survive into the era of fossil fuels. In this sense, I will argue that geography and ecology have shaped patterns of mobilization and governance that are still apparent today.

The argument will proceed chronologically, through periods of varying length. Within each period, the book's chapters will survey different regions of Inner Eurasia, relying loosely on a distinction between heartland regions, the primary drivers of change, and other parts of Inner Eurasia whose influence was less far-reaching. I have tried to structure the argument so that, while it brings out the coherence of Inner Eurasian history as a whole, readers can also pick and choose to get an overview of the distinctive histories of different regions: the lands west of the Volga which became the Russian imperial heartlands, the urbanized lands of Central Asia both in the west (lands dominated by the Russian and Soviet empires for much of the twentieth century) and the east (Xinjiang), the Kazakh steppelands, Siberia, and also Mongolia (the heartland in the thirteenth century).

NOTE ON GEOGRAPHICAL TERMINOLOGY

In a book that covers the history of half of Eurasia over more than half a millennium, geographical terminology can be extremely confusing. In the Soviet period, the phrase “tsentral'naia Aziia” referred to modern Xinjiang, to Central Asia east of the Pamirs, while English-speaking scholars have often used the phrase “Central Asia” for Soviet Central Asia, sometimes also including Kazakhstan and parts of Xinjiang. Xinjiang itself is a modern name, first used systematically from the eighteenth century, for a region previously known as Turkestan or Moghulistan.

For the sake of clarity, and at the risk of anachronism, I have adopted some arbitrary labels to refer to major regions of Inner Eurasia.

Moving from west to east, I will often refer to three broad divisions: Western, Central, and Eastern Inner Eurasia, with the Volga river and the Altai as rough border markers (Map 0.5). These divisions break the steppes into three major regions, which I will refer to as the Pontic steppes, the Kazakh steppes, and the Mongolian steppes. As we move from north to south, each of these three regions includes forest lands, regions of steppe and arid steppe or desert, and more urbanized southern borderlands.

Map 0.5 Major regions of Inner Eurasia. Adapted from Encarta.

I will use the term “Central Asia” to include the entire Central region south of Siberia, so it includes both the Kazakh steppes and the agrarian and urbanized region south of the Kazakh steppes, which I will describe as “Transoxiana.” I will use the modern term, Xinjiang, to refer to eastern Central Asia, those parts of Central Asia that lay east of the Pamirs and south of Mongolia and Siberia, and are now part of China. In earlier periods, I will sometimes use the more ancient term “Moghulistan” for Xinjiang. The Silk Roads threaded their way through northern Xinjiang, which includes the regions I will describe as Zungharia and Uighuristan. Zungharia is the region of steppe, farmland and towns that lies to the north west of the Tarim basin within modern Xinjiang. Semirechie lies within modern Kazakhstan, but is really a western continuation of Zungharia. I will use the term, Uighuristan for the region of steppe and desert east of Zungharia and north of the Tarim basin, taking the oasis of Hami/Kumul as a rough dividing point between Zungharia and Uighuristan. Southern Xinjiang is dominated by the Tarim basin or Altishahr, the southern parts of Xinjiang surrounding the terrible Taklamakan desert. I will normally use the term Mongolia to refer to the land included today within independent Mongolia, while the term “Inner Mongolia” refers to the southern parts of Mongolia that lie, today, within China.

Many other terms will be used only where historically appropriate. I will refer to the Principality of Moscow before the sixteenth century, to Muscovy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and to the Russian Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, while I will refer to the Soviet Union (or the Soviet Empire) for most of the twentieth century.

From the seventeenth century onwards, I will use the term “heartland,” not for the whole of Inner Eurasia (which is how the geographer Halford Mackinder used the term because he saw Inner Eurasia as a global heartland), but for those regions that had the greatest impact, the primary drivers of Inner Eurasian history. In the eight centuries covered by this volume, the heartland shifted westwards. In the thirteenth century, it lay in the Mongolian steppes, with Karakorum as its capital. It was dominated by pastoral nomads. After the collapse of the unified Mongol Empire in 1260, there was no clear Inner Eurasian heartland until the seventeenth century, though it is possible to identify several regional “heartlands.” From the seventeenth century onwards, it makes sense to describe Muscovy and the Russian Empire as a new heartland, which would eventually expand to embrace as large an area as the Mongol Empire. China, though not itself part of Inner Eurasia, was a powerful driver of change in the eastern parts of Inner Eurasia from the thirteenth century to today.

NOTE ON SPELLING

Spelling and transliteration of words and names from many different periods, countries, and languages is as tricky as geographical terminology. I have aimed at internal consistency, and all the names I have used can be found in reputable scholarly sources. But, beyond that, I have preferred simplicity and ease of recognition over linguistic precision and consistency in transliteration. This means that I have preferred Khrushchev to Khrushchëv, Hulegu to Hüle’ü (I have dropped a lot of diacritics in the body of the text because they mean little to non-specialists), and Karakorum over Qaraqorum. It also means that the spellings I use are those most likely to be recognized by English-speaking users (thus, Kiev rather than Kyiv). In choice of spellings, my primary goal has been ease of reading for those who are not specialists in the many different histories surveyed in this volume.

Many place names have changed over time. The Mongolian capital in the nineteenth century was known as Khuriye and, by most foreigners, as Urga. Today, it is Ulaanbaatar. The Russian capital, St. Petersburg, became Petrograd in 1914, and Leningrad in 1924. In 1991, it became St. Petersburg once more. As much as possible, I have tried to use contemporary names, though I have often included reminders of different names that may be more familiar to modern readers.

NOTE ON CHRONOLOGY

Until February 1, 1918, the Russian Empire used the Julian calendar, which by this time was two weeks behind the Gregorian calendar, used in western Europe since the sixteenth century. The dates given in this book are those that would have been used by contemporaries if they used either of these calendars. For the Russian Empire this means that I use dates according to the Julian calendar before February 1, 1918, and then Gregorian dates after that date (February 14, 1918 under the Gregorian calendar). This means that dates for the Russian Empire before February 1, 1918 are 14 days behind those for the same date in Europe, but normally this difference is not significant. Where it may matter, some sources give dates according to the Julian calendar (OS or “Old Style”) and the Gregorian calendar (NS or “New Style”). Thus, the “October Revolution” (OS) actually took place in November according to the Gregorian calendar (NS), so some sources describe it as the November Revolution. For the same reason, some sources say that the Tsar resigned in February rather than March 1917. After February 1 (February 14 NS), 1918, when the new Soviet government adopted the Gregorian calendar, there is a chronological gap of two weeks during which nothing happened because the day following February 1, 1918 (OS) was February 15, 1918 (NS).

NOTES

REFERENCES

- Abu-Lughod, Janet L. Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250–1350. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Bassin, Mark and Gonzalo Pozo, eds. The Politics of Eurasianism: Identity, Culture and Russia's Foreign Policy. London: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2017.

- Biraben, J. R. “Essai sur l’évolution du nombre des hommes.” Population 34 (1979): 13–25.

- Chaisson, Eric. Cosmic Evolution: The Rise of Complexity in Nature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Christian, David. A History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia, Vol. 1: Inner Eurasia from Prehistory to the Mongol Empire. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1998.

- Christian, David. “‘Inner Eurasia’ as a Unit of World History.” Journal of World History 5, No. 2 (Sep. 1994): 173–211.

- Christian, David. “Living Water”: Vodka and Russian Society on the Eve of Emancipation. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990.

- Christian, David. Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History, 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

- Christian, David. “The Return of Universal History.” History and Theory 49 (2010): 6–27.

- Hedlund, Stefan. Putin's Energy Agenda: The Contradictions of Russia's Resource Wealth. Boulder, CO and London: Lynne Rienner, 2014.

- McEvedy, C. and R. Jones. Atlas of World Population History. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

- Taagepera, Rein. “An Overview of the Growth of the Russian Empire.” In Russian Colonial Expansion to 1917, ed. M. Rywkin, 1–7. London: Mansell, 1988.

- Wolf, E. R. Europe and the People without History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

- World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2002.