“I knew I was alone in a way that no earthling has ever been before.” – Michael Collins

The launch operations for Apollo 11 began in the early morning, on July 16, 1969, with the fueling of the Saturn V launch rocket. Though many operations were automated through multiple software programs, there were still thousands of personnel at facilities in the U.S. and various parts of the world supporting the launch.

The day of the launch, the crew woke up early, showered and had breakfast with Deke Slayton and the backup crew. At 06:30, after having put their space suits on, they went out to the launch pad. The first to enter the Command Module Columbia was Fred Haise from the backup crew. His task was to help the prime crew take their positions in the spacecraft. Once Armstrong, Collins, and Aldrin were each in their positions, Haise left Columbia and another crew closed the hatch. As the time of the launch approached, the rest of the support crew left the launch complex. Meanwhile, the cabin was pressurized, and hundreds of people were monitoring the launch from consoles.

The Saturn V AS-506 rocket launched Apollo 11 at 9:32 EDT, and minutes later, Columbia entered earth’s orbit and the rocket engine put it on its trajectory toward the moon. Collins reported the liftoff felt “as if a giant had grabbed my shirt front and started shaking.” Four hours after liftoff, Collins separated Columbia from the rocket stage and docked it with the Eagle, which had been stored just below the Service Module in the upper Saturn V rocket. Once the Lunar Module docked with Columbia, the upper Saturn V rocket stage was set on a different trajectory away from the moon to diminish the risk of future collisions.

Figure – Launch of Apollo 11.

According to estimates, one million people watched the launch of Apollo 11 from the vicinity of the Launch Complex. An outstanding number of dignitaries, government officials, including Vice President Spiro Agnew, and Former President Lyndon Johnson were present. Thousands of media representatives from the United States and 55 other countries came to witness the event, which was broadcast live in 33 countries on radio and TV, with an estimated audience of 25 million viewers in the United States. President Richard Nixon watched the launch from his office in the White House.

The spacecraft entered lunar orbit on July 19, where it performed thirty orbits while the crew observed the surface and assessed the conditions of their landing site in the Sea of Tranquility. Previous analysis suggested that the site was flat enough to not present unexpected challenges during landing operations or extravehicular activities.

On July 20, at 12:52UT, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin entered the Lunar Module and started to prepare for descent to the lunar surface. Hours after completing a detailed checklist to prepare the craft, the LM separated from Columbia. Armstrong’s words "The Eagle has wings!" marked the moment. Collins would begin his lonely vigil in Columbia orbiting 60 miles (100km) above the moon’s surface until the pair returned from their visit to the barren world below.

Now the tensest phase of the entire mission began as the Eagle descended to the lunar surface. As the LM began its descent, Armstrong and Aldrin realized that they had greater speed than they expected, and this would cause them to go past their preferred landing site by a few miles. Meanwhile, the guidance computer showed several unexpected program alarms. Computer expert Jack Garman communicated with the astronauts from the Mission Control Center and reassured them that the issue did not affect their descent. According to experts, the alarms were triggered by an overflow of tasks, which the software managed by ignoring low priority tasks and thus preventing an abort.

The main problem the astronauts had to deal with was that they were too far from their intended landing site and over a dangerous rocky area, very close to a massive crater. Armstrong immediately took semi-automatic control, trying to direct the Eagle towards a different target as Aldrin focused on deciphering the navigation data. While they were at 107-foot (33 m) above the surface, Armstrong became afraid that the rapid loss of propellant would put them in a dangerous position. Landing, however, proved challenging due to the massive number of craters. When they were at 100-foot (30 m) from the surface, they realized they only had 90 seconds of propellant left. Fortunately, Armstrong found a patch of level ground and rapidly directed the Eagle towards it.

The Eagle landed on the moon at 20:17:40 UTC, on Sunday, July 20. It had only about 25 seconds of fuel left, which meant that any further delay would have been extremely dangerous. After shutting down the engines and completing other landing tasks, Armstrong communicated the Eagle’s position to Charles Duke, the CAPCOM at the Mission Control Center: "Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed." Duke responded with expressions of profound relief as he and all the listeners realized by Armstrong’s words that the landing had been successful.

After the landing, before preparing for the moon walk, Aldrin sent a radio message to earth, asking listeners to contemplate the magnitude of the events they were witnessing and to express their gratitude in their own personal ways. A devout Presbyterian, he then proceeded to take communion privately as astronauts were instructed to not use their authority to broadcast religious messages from space.

The official schedule of the mission included a five-hour sleep period for Armstrong and Aldrin, immediately after landing. Since they felt they couldn’t fall asleep, they began preparations for the moon walk instead. Preparing to exit the LM took them three and a half hours, much longer than they expected. Arranging their equipment and materials in the tight space of the cabin proved challenging as they had many important items lying all around, which during tests had been arranged in advance. Once everything was set, Armstrong and Aldrin depressurized the Eagle and opened the hatch. Armstrong squeezed through the hatch, but his movements were slowed down by the heavy portable life support system. He stepped down the ladder and began his descent to the lunar soil. While still on the ladder, Armstrong activated the TV camera attached on the Eagle’s side. Because Apollo 11 used slow-scan television, which was different from broadcast TV, the quality of the picture was very low. Even with the technical difficulties that affected the quality of the transmission, 600 million people on earth were able to witness the astronauts’ operations on the moon in black and white images, broadcast by TV stations from all over the world.

Stationed on the ladder, Armstrong then proceeded to reveal a plaque mounted on the Eagle’s descent stage. The plaque carried two drawings of earth, the signatures of the astronauts and of the president of the United States, and an inscription with the following words: “Here men from the planet earth first set foot upon the moon, July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.” Armstrong then described the lunar surface and while stepping onto the lunar surface, he uttered the following historic sentence: "That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind."

Figure – Man’s first foot print on the moon.

The first thing that Armstrong did after stepping on the moon was to collect a soil sample just in case he would be forced to return hastily to the Lunar Module. After collecting the sample and tucking it into one of his pockets, he took the TV camera from its position and mounted it to a tripod so the viewers from earth could follow the operations. The astronauts later used a handheld Hasselblad camera to take several pictures of the lunar surface. Twenty minutes after Armstrong, Aldrin exited the Lunar Module, exclaiming: "Beautiful, beautiful! Magnificent desolation." He was struck with the shocking contrast of the pale colors; many shades of gray, a pale tan, and areas of utter black where the rocks cast a razor-sharp shadow in the airless world.

Once Aldrin joined Armstrong on the lunar surface, the two astronauts proceeded to test methods of moving in the new environment, due to the differences between moon’s gravity and earth’s. They later agreed that maintaining balance did not present any difficulties, and they found no trouble walking around. The soil was, however, slippery and they had to watch carefully every step.

In front of the TV camera, Aldrin and Armstrong planted a U.S. flag on the lunar surface. While jamming the pole into the hard lunar surface wasn’t easy, they succeeded after some struggle. Immediately after, President Richard Nixon called them from the White House in a special transmission and congratulated them for the impressive achievement. During the conversation, Nixon declared that this “certainly has to be the most historic phone call ever made.” He continued, “Because of what you have done the heavens have become a part of man’s world. And as you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquility it requires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to the earth.”

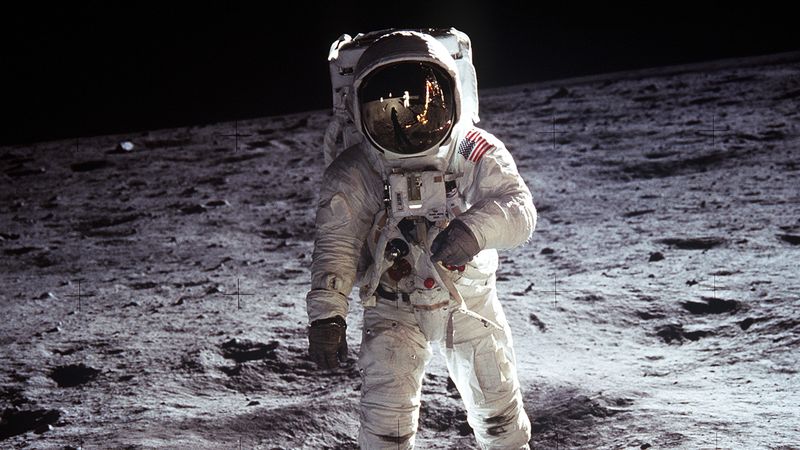

Figure – Buzz Aldrin on the moon.

After the call, Armstrong walked from the Lunar Module and snapped some photos of the nearby crater and the surrounding areas. He and Aldrin also collected geological and rock samples but found it impossible to penetrate more than a few inches deep with the hammer. Soon they realized that most of the operations had taken them longer than anticipated, and while Armstrong moved quickly from task to task to save time, he received a warning from Mission Control that his precipitous movements caused his metabolic rates to rise. He slowed down, and the Mission Control agreed to extend their schedule for the moon walk by 15 minutes. While Armstrong accomplished his tasks, Aldrin documented the trip and took most of the pictures.

Before entering the LM, Armstrong remembered that Aldrin had a memorial bag with the Apollo 1 mission patch and other symbolic objects in one of his pockets, which they wanted to leave on the moon. The bag also contained a silicon message disk, carrying the goodwill statements of several American presidents and leaders from all over the world.