7

The Nature of Te

In some translations of the Tao Te Ching, the sections on the Tao and Te are presented separately. Te is a difficult word to translate; it refers to action, virtue, morality, beauty, and gracious behavior. Te is the manifestation of the Tao within all things. Thus, to express the fullness of Te means to be in perfect harmony with the original nature of self and all things.

From the Taoist point of view, Tao and Te cannot truly be understood as separate. They differ only in terms of the order in which they are approached first: that of meditation or cultivation. Tao is based on meditation; Te is rooted in cultivation. To meditate is to gather and circulate Chi; to cultivate is to abandon the ego and to purify the consciousness.

In Taoist inner alchemy, Tao and Te are equally important. Yet to manage both simultaneously is a challenge, rendering the practice unrealistic. The practice of distilling the mind can appear daunting when the body is truly hungry. It would be equally unmanageable to purify the body if the mind was not fully prepared to offer the proper environment.

Once the seed of Tao is germinated, the action of Te takes place. Tao is invisible and Te is visible; Tao is intangible and Te is tangible; Tao is impersonal and Te is personal; Tao is motionless and Te is lovable; Tao inhales and Te smiles. Because of this esoteric transformation, matter is visible, form is tangible, substance is manageable, and trust is reliable. They are all the virtuous expression of Te resulting from the emerging power of the Tao.

The exhalation of Te is the sum of all human activities that have been conducted with moral judgment and supervised by the spirit. When in concert with the kind action of Te, all are inspired, encouraged, and uplifted; every action is honorable, respectable, and appropriate.

In the last exhalation in life, the purified Shen gathers the elixir or remaining energies lingering in the body and, guided by an enlightened master or an angel, exhales this through the top of the head instead of the mouth or nose. This transpires only after kind action or Te has been completed and all debts have been paid. Unless these conditions are met, the person will die as either a hungry ghost or wandering ghost.

This task can be endeavored by cultivation as well as meditation. The meditation of love can be transformed into the cultivation of virtuous action, qualified by kindness, goodness, harmony, impartiality, integrity, and holiness. Love will no longer be a mental projection but a true and honest expression of empathy, care, and concern born from nonseparation between self and other. As the power of meditation and the outcome of cultivation generate virtuous action, the sage embraces and integrates the animal, human, and divine aspects of the self.

VIRTUOUS ACTION

From the Taoist point of view, Te is what Tao “drops.” Lao Tzu writes that When Tao is lost, it becomes Action (38:3). The word “lost” represents the complete transformation or evolution from one state of being into the next. When the infinite and unmanifest Tao is surrendered into active Te, it becomes visible. Te represents the highest state of the transformation of Tao into matter and substance, retaining the highest essence of the Tao. It is a descent of the unmanifest into the manifest.

This descending process is quite similar to the supernatural power or influence exerted by a divine being. Lao Tzu also describes Te as mystic action. Yet Taoism doesn’t create a sharp distinction between natural and supernatural.

[T]he person who works according to Tao unites with Tao.

In the same way he unites with action.

In the same way he unites with loss.

Uniting with action, the Tao becomes action.

Uniting with loss, the Tao becomes loss.

(24:4–5)

Lao Tzu explains that the person who works according to Tao unites with Tao. In the same way he unites with action (Te). In the same way he unites with loss. The power of Tao becomes the seed of life, emerging as the elixir of virtue or evaporating into nothing. Thus Tao saves the spirit or loses the earthly life. Returning home with virtue is saving the spirit; marching forward toward the grave is loss.

The original meaning of Te in Chinese involved the idea of “ascending” or “elevating,” indicating the uplifting of the human spirit rising from the earthly carnal body into pure spiritual action. This is consonant with the English understanding of virtue, which implies moral practice and action, conformity to the standard of right, moral excellence, integrity of character, upright conduct, and rectitude.

Yet virtue cannot be understood simplistically, according to prescriptions or rules. Te, or virtuous action, is a spontaneous and interactive engagement between body and mind, perception and response; it is the judgment of good and bad, and the conduct of divine and ordinary. Nature acts, humans perform; nature presents, humans exhibit; nature reveals, humans display; nature manifests, humans conduct; nature shows, humans behave; nature embraces, humans value; nature integrates, humans dissolve; nature unifies, humans separate.

Virtue, to the ordinary mind, is something remote, pure, and out of reach. It is a moral quality suited only to a divine being. Virtue is something that we can think about and strive for, but cannot perform. We can visualize it but cannot perceive it; we can comprehend it mentally but cannot engage it physically.

Xiaochu and Dachu

The inner alchemy called forth by walking the path of Tao and Te is addressed in the I Ching hexagrams Xiaochu and Dachu, which we discussed briefly in Chapter 4. In the I Ching there are two mystical energy fields, the small mystical field (Xiaochu) of the ninth hexagram and the larger mystical field (Dachu) of the twenty-sixth hexagram. Xiaochu deals with the animal body and its spirit, while Dachu refers to the human body and its spirit. The Taoist path involves integrating these two fields within ourselves. We need to be in harmony with the energy field of mother earth and be able to transform the energies of the earth. Yet we also need to be in harmony with the energy field of the human realm, so we can walk the way of beauty, compassion, values, and justice—the virtuous action of Te.

SMALL MYSTICAL FIELD (XIAOCHU) OF THE 9TH HEXAGRAM

LARGER MYSTICAL FIELD (DACHU) OF THE 26TH HEXAGRAM

The small mystic field deals with the small mind, the selfish, egoistic, and culturally conditioned mind. The large mystic field houses the selfless and cosmic mind. Energetically, the small mystic field deals with the biologically driven, instinctive actions of self-preservation and survival. It has no concern for the world other than what it can provide the seeking acquisitive eye and the craving hungry stomach. In the large mystic field there is no self-preoccupation, self-protection, or self-concern of the small, egoic self. There is instead a sense of self/mind that is vast and unlimited by the needs of the ego and animal nature.

The ninth and twenty-sixth hexagrams, Xiaochu and Dachu, both have the same lower trigram: the creative power of the cosmos and the invisible light of heaven. In Xiaochu, the upper trigram is wind, representing the heavenly order, conscious awareness, and instinctive behavior. As a whole, the characteristics of Xiaochu are mobility, agitation, unsteadiness, and unreliability. Cloudiness, murkiness, rigidity, and scattering are its tendencies. Mind is windy with no clear mental picture. There are clouds but no rain, wandering but no awakening, only confusion with no self-understanding. There is no awakening of the inner character.

In contrast, Dachu’s upper trigram is replaced by mountain, agitation by stillness, mobility by self-action, unsteadiness by steadfastness, unreliability by trust. When the mountain grounds the spirit and nourishes the soul, the mind is clarified, the body is purified, the attitude made flexible.

The self is never lost, the energy is never exhausted, and spirit is never dead. The sage is not bounded. He sustains himself from the mother resource and does not rely upon family in order to continue his existence. He is everywhere in the world and has no need to be protected and comforted. He is clothed with light, breathes the vital force, and settles down in the universe.

Dachu points to light and clarity and to the daily renewal of character. Dachu points to walking the way of the Tao and manifesting in the world as Te.

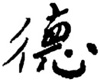

The Te Ideograph

In the construction of the Chinese ideograph Te, the right side of the character is composed of four characters, “hand,” “vessel,” “one,” and “heart.” This part of the character can be expressed as “The single heart supports and directs the vessel of the body carried by the hand.” Truly, the body is the most sacred vessel, and the hands are the most powerful and useful tools. Yet, without heart there is no foundation; without the single-minded heart, there is no transformation. This part of the ideograph depicts a meditative state in which hands are unified with the bodily vessel and guided by the single devoted heart.

CHINESE CHARACTER TE

This action is accompanied by the careful steps of walking, represented by the left side of the character. The activity of the hands is freed from concern with the bodily vessel. Chi sustains the vessel and satisfies the heart. The hands are held together as in a meditative state. The world is in its perfect order and the body/mind is in its perfect harmony.

There is one remaining aspect of the Chinese character that expresses the meaning of Te. It implies that perception is grounded in the heart, the heart is grounded in spiritual consciousness, and spiritual consciousness is grounded in the character of nature. Everything is there and nothing is there. All the lines, angles, joints, and points of the ideography of Te are penetrated, purified, and transformed by the fire of light. This is the magic play of a sage who dwells in the Tao and moves in Te.

KIND ACTION

While the forces of nature are impersonal and impartial, even inhumane, human souls are called to empathy, kindness, and compassion. Te refers equally to virtue and kindness. When the small ego no longer rules one’s life, one’s action is kindness itself. In practicing kind action, love is no longer a conscious game played by ego. It no longer functions as an obsessive mental longing or uncontrolled emotional outburst. Sympathy becomes mutual encouragement. Pity becomes the fearless act of loving. Negative emotions do not hurt people and positive emotions cannot drag them down. All these emotional attributes are purified into compassion.

He is kind to those who are kind.

He is also kind to those who are not kind.

It is the kindness of Action itself.

He is trustworthy to those who are trustworthy.

He is also trustworthy to those who are not trustworthy.

It is the trust of Action itself.

(49:2)

When selflessness is restored through the meditation of love, action is kind and trustworthy. When the universal loving energy is gathered within, biological and psychological needs are fulfilled, thereby leaving no room within the body and mind for desire and demand created by ego. Self-trust is established and conscious fear is relinquished. One’s energy is then free and fully available.

When the sage uses the universal loving energy, his action is both kind and trustworthy. He is kind and trustworthy to all—to those who are kind and trustworthy, and to those who are not kind and trustworthy. Through kind action, both kind and unkind people are unified. Those who are kind transform those who are not kind. There is no separation between what a kind person is and the kindness itself. Those who are not kind benefit from those who are kind, and kindness itself is then underway. Those who are trustworthy improve themselves and know there is more trust in the future. Those who are not trustworthy disprove themselves, yet trust welcomes them along the way.

Through love, kind action becomes endless, inexhaustible, and unfathomable. Kind action is the very nature of a mother’s power of creative nourishment, a combination of selfless love and self-sacrifice.

Te Is Smallness

The way of Te is smallness, simplicity, integrity, peace, noncompetition, and nonaction. Being small allows for growth, expansion, and development. It is the most effective way to conserve energy since the small consumes minimal energy. Once the humbleness of the honest heart steps in, the opportunism of the egoistic mind is cast out, and the desire for achievement and recognition becomes illusory.

Simplicity is the way to direct your life. There is no confusion to deal with, no mind juggling, and no disguise. With no attachment, each minute detail and quality of smallness will manifest. Just as with a newborn baby, smallness requires your full attention, the finest care, and the highest precautionary measures. Any slight of mindfulness or unintentional carelessness could cause immediate difficulty.

Realizing this, everything manifests by itself, naturally; even the method of simplicity is absent. Any intervening thought, calculation, or effort is eliminated. In smallness there is peace. Through peace, one observes that vast action seems yielding (40:3).

In smallness and simplicity, one’s ego is out of the way, therefore there is room for all. Such is called mystic Action. For that reason, all things worship Tao and exalt Action. The worship of Tao and exaltation of Action are not conferred, but always arise naturally (51:1-2,5).

Humility and Humiliation

Humiliation is one of the most devastating emotions one can face. Lao Tzu says that “Favor and disgrace surprise the most.” The word disgrace is synonymous with humiliation, a reaction no one wishes to experience. When humiliation occurs, the conscious mind is completely darkened and filled with despair, placing the recipient into a despicable state with no opportunity to hide or escape. It renders one valueless, seemingly nonexistent. On the other hand, it evolves into the most valuable time to examine oneself objectively, to face the situation with grace and understanding, to become like a child, and glorify God once again. The recipient owes thanks to the person invoking the humiliation. This experience can support the cultivation of humility, where one is not attached to one’s self-image, to self-importance, or to position.

The essence of getting in touch with humiliation is to purify oneself from distortion, conceit, and pride, and to discover the impersonality of life, which will endlessly run its course. The following is a liberating meditation that works with humiliation.

- Mentally picture the scene that precipitated your humiliation. Feel the presence of the thoughts and feelings involved.

- Stay with the pain and suffering, and hold this experience for awhile. Then release all the energies, thoughts, and feelings associated with the humiliating experience. Let it all go, at once, and be liberated.

- Do not be angry and frustrated about your humiliation. Look into it objectively. What does this humiliation mean? What was its purpose? What did you learn about your attachments and self-image?

- Handle the humiliation just as you do the blowing wind or daily, mundane events of life. It is not personal and should not be pondered as anything special. This does not suggest that blowing wind and daily events are nothing, but that all things existing in life are normal and impersonal, and nothing about them is special.

- You will find that in being humiliated there is attachment to expectations, and a certain lack of self-esteem and freedom. Destroy any rigidity you feel within you that prevents to from being open to new and unexpected things.

- Allow your humiliation and your mind to be painstakingly purified in the same way that your body could be objectively examined and the source of its illness surgically removed. The full realization of this humiliation process is having your identity, position, esteem, and self-worth purified.

- Decide if you will allow your body/mind to heal itself. Do you prefer to cling to the pain for reasons you may not be fully aware of?

- The lesson is how you can free yourself from burdensome feelings and situations. Be aware that further humiliations may be in store, but now you are better prepared to deal with it should it arise.

True Dignity and False Dignity

Dignity is the quality of being worthy, honored, or esteemed. There is the essential dignity of the simple, unselfconscious expression of virtuous action. This is the dignity of Te. There is also the self-concern of the ego with its self-image. This is driven by insecurity and fear, and is not true dignity. With genuine self-esteem, cultivated through living in accord with Tao and Te, comes true self-dignity.

Self-dignity is totally opposite to ego-dignity. The conscious center of self-dignity is none other than conscious awareness. It is a state of openness, centeredness, and responsiveness.

It is not surprising that true self-dignity releases us from imprisonment in self-concern and self-image. True self-dignity has greater power than ego-dignity. Ego-dignity, which is an insatiable need for affirmation, is driven by selfishness, ethnic and other limited identities, and unconscious belief patterns. When controlled by ego dignity, forgiveness, acceptance, generosity, kindness, and compassion are lost.

In a world of “me first,” above all others, how can we begin to contemplate Te, virtuous and kind action? With selfishness at the helm, people think moral action is the purview of only rare humans and divine beings. This denies the reality that unconditional, selfless, and universal love is the foundation of Being.

Love, compassion, and generosity are the expression of true self-dignity. These qualities are the natural expression of one who is released from self-concern.

TE CULTIVATION

Ji Te

Ji Te refers to the spiritual work of transforming the biophysical body into the loving Chi body used to express beauty, virtue, and compassion of Te in the world. The word ji means “accumulate.” Ji Te is accumulating Te, the most challenging homework in all spiritual practice, more demanding than meditation and more difficult than sharing and giving. It is a constant purification process. Te is an objective energy but not a concrete object to be identified and possessed. Ji Te is the cultivation of kindness, loving energy, and self-sacrifice. The Taoist practices that accumulate and transform sexual and emotional energies are part of the path of Ji Te.

Ji Te is the process of establishing the quality of Te character. Without an accumulation of Te, there is no objective quality to be perceived by others. It is this accumulative practice, day after day, event following event, and trial after trial, that dissolves the ego, purifies the body, and distills the mind.

In our society there are many meditation techniques to learn, many skills to master, many opportunities for status seekers. Ji Te can be taught but cannot be learned intellectually. You cannot process Ji Te with the mind; you simply sacrifice your life to its practice. It is more painful than any sickness, more degrading than humiliation. It entails suffering. One must overcome any number of blockages.

No one can give someone else Te, even though they may be the recipient of its loving kindness and hospitable generosity. Any student desiring to cultivate the character of Te will quickly learn that it cannot be mastered by learning from others. It must be a process of self-mastering. Je is the manifestation of cosmic kindness, the mystic Tao in kind action. Ji Te is cultivating our capacity to be Te and express Te. It is the heart of the spiritual path.

The Mind as a Servant

From the perspective of the mind, spiritual cultivation begins in the self and ends with no-self. It is the transformation from mental engagement to full, mindful awareness. The Taoist’s perspective is that spiritual cultivation begins with no-self and culminates in universal self. This is the path that culminates in the seamless expression of Tao and Te. No-self refers to the pure self that is not colored by the rational and intellectual mind, nor distracted by the craving and egoistic heart. No-self is the power of wisdom mind as well as the space of pure heart.

In the spontaneous expression of Te, there is no calculating mind. There is no conceptual mind standing back from the situation and observing, judging, commenting, claiming. Knowledge, to Lao Tzu, is mental information acquired by conscious desire or egoistic persuasion. Knowledge is something that can at times be useful, but the intellectual mind must serve its proper role, as a servant, not a master.

To obtain knowledge is necessary, but to apply it in accordance with Tao and Te requires great skill. The mind can become a slave to knowledge. Trying to obtain it can be an obsession. When the nature of knowledge is understood, it use is transformed, and it can serve and support virtuous action. True virtuous and kind action does not conform to the habits of mind. It does not serve the demands of the ego. It can be fully experienced but can never be thoroughly explained; completely envisioned but never absolutely understood; mindfully anticipated but never analyzed with detail. Spontaneous, natural, right action is no-minded.

When intelligence arises, there is great deal of manipulation (18:1). The obsessive intellectual proliferation of the ordinary mind makes people unhappy and society chaotic. C. G. Jung corroborates Lao Tzu’s assertion when he writes, in Memories, Dreams, and Reflections, that “in my experience, therefore, the most difficult as well as the most ungrateful patients, apart from being habitual liars, are the so-called intellectuals. With them, one hand never knows what the other hand is doing. They cultivate a ‘compartment psychology.’ Anything can be settled by an intellect that is not subject to the control of feeling—and yet the intellectual still suffers from a neurosis if feeling is undeveloped.” The intellectuals can never bring in harmony what they think with what they feel. They cannot harmonize their inner experience with the virtuous action of Te. They walk through the narrow tunnel—constant logical calculation and intellectualization—that plagues modern Western civilization.

It is only when the intellectual capacity becomes still and quiet that the desires and cravings of the heart also become quiet. Only when the egoistic mind is dispelled can the true self take its rightful place. When the mind is peaceful and tranquil, the mind’s natural illumination, originality, and wisdom can come forth. This is a intelligence that is far beyond anything that can be taught. It is linked with every individual’s pure and uncarved innate ability. When this ability connects to its source, it becomes the universal-self.

In order to achieve this, one must master the self, the seed of the Tao. Cultivate the self, and the action is pure. Treat the self by the standard of self. We focus on awareness, listen to the heart, speak through the mouth, project through mentality, and battle with non-self and false-selves. We do all of this with authenticity and intention, and strive to unify and align all the many parts of the self with the Tao. When all these bits and pieces of the self are unified and crystallized through the nature of Tao, there is no longer any compartmentalization, and there is no difference between oneself and others. Then our life energy is no longer drained or dispersed through division, ambivalence, or distraction. There is an inner freedom in which we are truly present and truly available; we can respond fully in Te, kind and virtuous action.

True Te and the Veneer of Te

One of the most important distinctions Lao Tzu makes in the Tao Te Ching is that between no-minded, egoless, spontaneous action, and self-conscious, ego-centered, planned action. This is the distinction between Wu Wei, which means “actionless action” or “nondoing,” and the unnatural, ego-based, forced doing that consumes so much energy in the world. Wu Wei refers to action or response that arises spontaneously and effortlessly from a deep sense of nonseparation between oneself and one’s environment. Wu Wei is behavior occurring in perfect response to the flow of the Tao.

Eminent action is inaction,

For that action it is active.

Inferior action never stops acting,

For that reason it is inactive.

Eminent action is disengaged,

Yet nothing is left unfulfilled;

Eminent humanness engages,

Yet nothing is left unfulfilled; . . .

(38:1–2)

When eminent action descends into inferior action, spontaneous action devolves into self-conscious action. Ego-based self-righteousness arises, and judgment steps into the picture, and reduces the results of engagements. Once righteousness is dispersed, eminent justice engages but does not respond adequately to situations. For that reason it is frustrated (38:2).

When Tao is lost,

It becomes Action;

When Action is lost,

It becomes benevolence;

When benevolence is lost,

It becomes justice.

When justice is lost,

It becomes propriety.

Propriety is the veneer of faith and loyalty,

And the forefront of troubles.

Foresight is the vain display of Tao,

And the forefront of foolishness.

Therefore, the man of substance

Dwells in wholeness rather than veneer,

Dwells in the essence rather than the vain display.

He rejects the latter, and accepts the former.

(38:3–7)

A truly good man is not aware of his goodness; this is the nature of his goodness. He is not aware of himself as good. He is not aware of doing good. He just responds to life spontaneously, the response not separate from perceiving the situation, himself not separate from the situation.

Justice, as Lao Tzu describes it, is what arises when kindness is lost. Tao devolves into goodness. Goodness devolves into kindness. Kindness devolves into justice. Justice devolves into ritual.

The kind of justice that Lao Tzu refers to here indulges in self-justification and self-protection. It bears no resemblance to Te. It is based upon aggression and the counteraction of that aggression. Fairness, in the practice of justice, is not true fairness. Before the strong arm of justice, the fearless are in jeopardy and may lose their lives, but later, the karma of reaction surfaces. In the face of justice, the fearful can survive before final judgment is pronounced. Their physical bodies are temporarily protected, but their hearts cry out. As justice employs more and more procedures, society becomes more chaotic and disordered. That is not the nature of Tao; that is not kind action.

There is a clear-cut difference between moral discipline and social justice. Moral discipline consists of conscientious and virtuous deeds carried out through love and kindness. When love and kindness are remiss, the mind reacts unconsciously. Killing, stealing, lying, and all manner of “wrongful” behaviors arise. They serve the purpose of taking advantage of others (and ultimately harming oneself) in a failed effort to compensate for the deficiency of love and kindness.

From this comes righteousness, the standard judgment of moral conduct. When righteousness is lost in ego’s dominance and aggression, religious and political rules flourish, shaping social behavior by its own standard of righteousness. Rather than Te, spontaneously kind and virtuous action, society is shaped by dogmatic rules and procedures. It is the veneer of Te, not Te itself. Moral conduct is replaced by collective activities and expectations. A selective group is approved to positions of authority by the collective mind. Moral discipline becomes mechanical and superficial. Unconditional and selfless love descends into the conditional demands of selfish love. Kindness then becomes a tool for personal benefit and compassion becomes a guise for ego gratification. True kindness and virtue are lost in a maze of crude, dehumanizing, and rationalized rules that are defended by the ego. This is propriety, merely the veneer of virtuous action.

Not Possessing

When the self is unified it is able to enter into the mystical space of Wu Wei, or actionless action. The action of Wu Wei, though mysterious, is rather plain and simple.

Begetting but not possessing,

Enhancing but not dominating.

This is Mysterious Action.

(10:2–3)

Tao enlivens and nourishes, develops and cultivates, integrates and completes, raises and sustains.

It enlivens without possessing.

It acts without relying.

It develops without controlling.

Such is called mystic Action.

(51:3–5)

The actionless action that expresses Te begets but does not posses. It enhances, enlivens, and nourishes, but does not dominate. It does not claim ownership. There is just the action, just the Wu Wei. There is no self—no “I”—doing something. There is no subject (self) in relation to an object (other). There is no self in relation to an action. There is just doing. This is the purity of Te, of virtuous and kind action.