7 Woods and Forests

Foresters and afforestation

In some ways conservationists and foresters are much alike. Both are often keen on natural history, both enjoy working outdoors and believe their work will be of lasting value. Above all they share the same single-minded-ness. Just as a local conservation officer will tend to weigh up all the land in sight in terms of its ‘conservation value’, so a forester will view it in terms of its potential for planting trees. The forester plants trees in the belief that their benefits are self-evident. In his eyes, conservation designations threatened to sterilise land that was perfectly good for trees. As an NCC local officer, I well remember the aggressive questioning – almost the sense of outrage – from visiting foresters as they pointed out that this or that nature reserve or SSSI was perfectly capable of producing timber. Where was my willingness to compromise? (Answer: compromise invariably meant we lost.) The farming community was often half-apologetic about damaging SSSIs; foresters, in my experience, never. Instead they laid great store on concepts such as integration and multipurpose use, which generally allowed room for more planting. Local plans in Scotland and Wales tended to be very generous to forestry interests (new forests meant new jobs, thought the planners, and weren’t trees good for wildlife?). This shared single-mindedness meant that when forestry and nature conservation came into conflict, as they increasingly did in the 1970s and 1980s, the resulting struggle was bitter and protracted.

To begin with, though, the Nature Conservancy saw forestry almost as an ally. Some of the first generation of senior Conservancy staff came from a background in forestry, often in the colonial service. Fraser Darling considered that ‘the more forest there is the better’, and was inclined to see even the Forestry Commission’s ‘square green rugs’ of Sitka spruce as a benefit, since ‘after it is thinned out…other stuff could be used which are pleasanter trees altogether’ (Mackay 1995). Dudley Stamp (1969) thought that planting policies had improved a great deal since the 1930s, and that ‘introducing a range of conifers’ improved a dull old oak wood. As late as 1978, the NCC was publicly congratulating the FC on its recognition of ‘the needs of conservation and amenity’ and looked forward to ‘fruitful collaboration in the future’ (NCC 1978).

The problem with forestry in Britain lies in its scale, in the kinds of trees that are planted, the method of planting them and, often, in the places they are planted. By the late 1940s, most of our larger woods, as well as many smaller ones, were in a bad state, having been plundered of their timber during two World Wars. At the same time, the timber market had shifted from slow-growing hardwoods such as oak and beech towards fast-growing softwood conifers grown mainly for pulp and pit-props. In the cold, wet climate of the hills, where most plantations are situated, the most successful tree is Sitka spruce, a native of oceanic north-west America. Great things were claimed for the universal spruce: it would create a strategic reserve of timber, save imports and create jobs in deprived areas, as well as diversify the habitat. Other favourites are larch from Japan and lodgepole pine, also from North America. In the 1950s, the Forestry Commission was still planting oak and other native hardwoods on suitable lowland soils, but by 1984, 98 per cent of its plantings were non-native conifers, above all Sitka spruce. Conifers grown in commercial plantations are harvested, generally by clear-felling, at around 40 to 60 years old, and rarely achieve the graceful maturity of their native counterparts. Since the Commission’s main job is to grow marketable timber as cheaply and efficiently as possible, the crop trees are planted densely in straight rows, which, from the air, make the plantations look like carpet rugs. They replace the natural irregularity and variety of vegetation on the open hillside with, as nearly as possible, total uniformity. Plantations lack the structural complexity of native woods, with their developed layers of shrubs and herbage. In some there is practically no natural plant growth at all, apart from the odd wisp of fern and hummock of moss. Of course, even monocultures of foreign trees support wildlife, in the tree canopy, along the broad surfaced rides created for timber lorries, and in the clearings left after fellings. But modern tree-planting has closer affinities with arable agriculture than traditional woodmanship: the ground is ploughed, fertiliser, and sometimes pesticides, is applied, the nursery-grown seedlings are planted in rows, and later the crop is harvested in extensive clear-fells. Modern techniques, with their reliance on machines and the agro-chemical industry, change the physical and chemical nature of the soil and alter the natural drainage. Dense conifer plantations acidify the soil and drainage water. Forest hygiene demands the removal of the dead wood habitat. Broadly speaking, and despite all the propaganda to the contrary, commercially managed conifer plantations are not good for wildlife. Moreover, they block access to the open hill. Walking in them can be a funereal experience, despite the FC’s former chairman, Sir Robert Robinson’s evidently sincere belief that his plantations were much nicer to walk in than open country (Mackay 1995).

Even so, it was possible to persuade yourself, as Darling and Stamp did, that the austere new forests would eventually mellow into a mixed-species, pseudo-alpine environment with more concessions to amenity and wildlife. Back in the 1960s, afforestation was not widely regarded as a major environmental problem in Britain, mainly because there was still so much open hill land. The importance of ancient and natural woodland was not then widely understood, and the value of open moorland and blanket bog less appreciated. Even the NCC ‘improved’ some of its woodland nature reserves by planting trees, albeit native ones. It was assumed that pretty well all the great trees of the British landscape had been planted at some time; the rest was dismissively regarded as ‘scrub’. That was why there was so little resistance to what happened to our native woods between 1945 and 1985, when nearly half were clear-felled and replaced by crop trees (30 per cent) or farmland (10 per cent). By the 1970s, however, blanket afforestation was transforming entire landscapes in out-of-the-way places such as Knapdale and Kintyre, Galloway and the Borders, and parts of central Wales. There any requirement for ‘an acceptable balance with agriculture, the environment and other interests’, which the Forestry Commission was bound by statute to respect, seems to have been overlooked. The underlying rationale for the onward advance of Sitka spruce was that Britain should save on imports by becoming essentially self-sustaining in timber. But this was a pipe dream. By 1985, 2 million hectares – nearly 10 per cent of Britain’s land surface – lay under crop trees, but still met only 12 per cent of domestic needs (Sheail 1998). The FC’s prognosis was for a further 1.8 million hectares of new forest (other forecasts went as high as 2 million). If achieved, this would cover nearly two-thirds of the remaining afforestable land (NCC 1986) and have a drastic effect on the wildlife of the open hill. Astonishingly this misguided policy was accepted without much demur at Westminster, thanks to the influence of the forestry lobby in both Houses of Parliament. As protesters quickly discover, politicians, particularly in Scotland, tend to be forestry-friendly, seeing it as a source of ‘jobs’ while regarding open land as inherently inexhaustible and, in any case, as ‘barren wilderness’. The same is true, and for the same reason, of local authorities. Before 1980, opposition to afforestation had been led by amenity groups, such as the Friends of the Lake District, and individual naturalists. It was only in the 1980s that the NCC and the RSPB began to question the entire basis of forestry in Britain, and the public alerted to its lack of accountability in works such as Steve Tompkins’ Forestry in Crisis: the Battle for the Hills (1989). Unfortunately the NCC was unpopular in Scotland, while the Forestry Commission, whose headquarters were in Edinburgh, was regarded as part of the Scottish establishment. Before recounting these hill battles, let us briefly review the story of this body, whose decisions have been so important for wildlife in Britain.

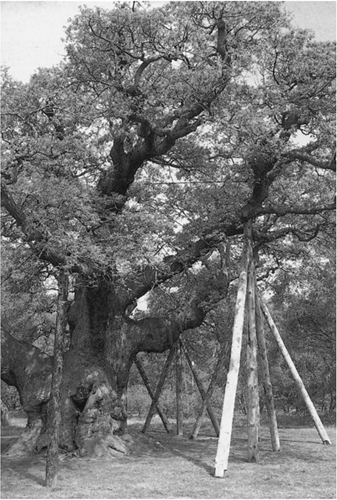

Near natural woodland at Bramshaw Wood in the New Forest – mature oak, an understorey of holly, open glades and plenty of dead wood. (Derek Ratcliffe)

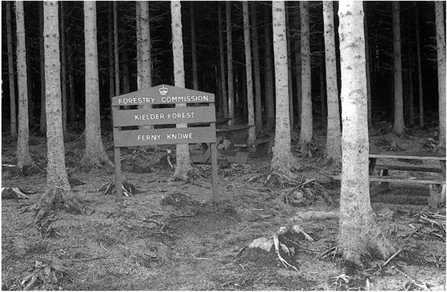

No more ferns at Ferny Knowe. This picnic site from hell was hastily dismantled after its appearance in Steve Tompkins’ book, Forestry in Crisis: the Battle for the Hills (1989). (Derek Ratcliffe)

The Forestry Commission

The Forestry Commission was set up in 1919 for the purpose of buying up cheap land for planting trees and ensuring that Britain had sufficient strategic reserves of timber to withstand another war (at that time the Royal Navy still depended on coal, and coal depended on an adequate supply of wooden pit-props). Although technically part of the agriculture departments, the FC has a unique status as an undevolved department of state, while having some of the characteristics of a quango. For many years it has been Britain’s largest landowner, owning 1,165,000 hectares (6 per cent of the land surface) in 1987. It has powers to buy and sell land, and provides grants and loans for others to plant trees. Until recently it also operated a dedication scheme whereby a private owner received tax exemption in exchange for devoting part of his land to timber production. In such cases, the owner in effect became the FC’s factotum under a management agreement. One way or another, the FC decides where, how and how many trees are grown in the UK.

In 1943, the Forestry Commission pressed successfully for a large-scale programme of reafforestation in order to achieve adequate timber reserves to fight another war, and also to help the balance of payments. It calculated that the nation needed some 2 million hectares of further planting over the next 50 years. Existing woods and forests could supply less than half of this. The rest would have to come from planting bare land. Some of the FC’s early plantings were an embarrassment – crude green rectangles and lozenges that made no concessions to the lie of the land, and so, quite apart from looking ghastly, proved vulnerable to storms and floods. There were many complaints, and, as a result of them, the Commission agreed to limit its activities in the Lake District and Snowdonia. With the appointment of Sylvia Crowe as an adviser on landscape in 1964, forest design improved in England and Wales, but she had little influence in Scotland where large-scale afforestation was being increasingly directed. Already planting in Scotland exceeded that of England and Wales put together, and was set to expand. From the 1970s, much of the planting target of 35,000 hectares per year would be met by private, tax-break forestry (see below). The FC turned itself into ‘a kind of sponsor for the private sector…not of promoting standards within that sector but of standing behind grant applications and assisting them in minimising the impact of agricultural and amenity objections’ (Mackay 1995). It forcefully opposed planning regulation, sought vainly by the Countryside Commission for Scotland for plantings of more than 50 hectares or within designated National Scenic Areas. It often gave planting permission to SSSI owners, thereby forcing up the land value, and making compensation more difficult and expensive. It was not until very late in the day, in 1985, that the Commission officially accepted a duty to achieve a ‘reasonable balance’ between forestry and conservation – and even then it interpreted this as ‘tarting up’ the forest, rather than refraining from planting up areas of nature conservation importance. On its own estate, very few natural woods had escaped partial or total felling and replanting with conifers. That many of the original trees did in fact survive was in spite of the FC’s best efforts, not because of them.

The FC began to reconsider the value of native hardwood trees and woods in the 1980s, prodded first by a parliamentary committee (which was, in turn, much influenced by the submissions of Oliver Rackham and George Peterken, incorporated in the NCC’s evidence), and then, in 1982, by an academic conference in Loughborough that brought leading foresters and woodland ecologists together. In July 1985, the Scottish Secretary, George Younger, announced a new policy aimed at ‘maintaining and enhancing’ broad-leaved woods. The amount of timber that could be removed without a licence would be reduced. The FC was not allowed to license the clearance of more woods for farmland ‘without very strong reasons’. Grants and tax incentives for planting slow-growing broad-leaved trees were increased, thus implicitly recognising that there were reasons other than productivity and profit for planting trees (for Britain’s oaks and ashes can never hope to compete on the timber market with cheap tropical hardwoods). The policy of ‘coniferising’ native woods was, in effect, abandoned. And the Commission now had the duty to balance the needs of both timber production and wildlife. All in all, it amounted to a formidable enforced U-turn. Good things followed. In 1986 the FC signed an agreement with the NCC over 344 SSSIs in its care, covering 70,000 hectares. By the early 1990s it had accepted the NCC’s Ancient Woodland Inventory (see below), which identified such woods, and provided guidelines for their care and maintenance. In 1988, an embargo was placed on ‘predominantly coniferous’ afforestation in England, and, from 1992, the Forestry Commission offered special management grants for woods of high conservation value. Today all SSSIs on the Commission’s estate are managed by agreement with the country agencies under formal agreements or statements of intent. Moreover, a substantial part of forestry research has been switched towards biodiversity and conservation.

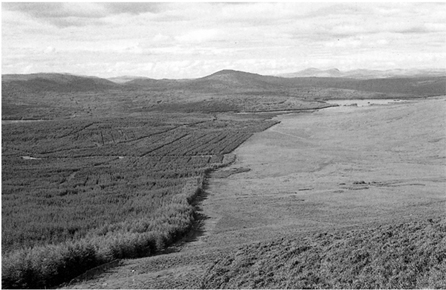

Fleet Forest advances like a dark green tide breaking against the Galloway Hills. The picture chosen to front the NCC’s critique of modern forestry, Nature conservation and afforestation in Britain (1986). (Derek Ratcliffe)

In 1992 the Forestry Commission was reorganised into two branches, a Forestry Authority, which continues its regulatory function, and Forest Enterprise to manage its estate. Under pressure from the Royal Forestry Societies, and from the public, concerned about restrictions on access, the Government decided against the wholesale privatisation of FC land. Conservation bodies found themselves defending the FC, presumably on the principle of ‘always keep ahold of nurse, for fear of finding something worse’. Personally, as the above remarks may betray, I think I would have risked it.

The planting of the uplands

In the 1970s a new phenomenon began to affect the upland scene – the private-sector forestry companies. A sharp-eyed accountant had spotted an opportunity to make money out of planting trees by exploiting a tax loophole. What was more, technology now enabled timber growers to grow trees on peat bogs. Experiments using lodgepole pine as a nurse crop for the ubiquitous Sitka spruce suggested how it could be done: the growing pine dries out the peat, and, having done its job, it dies, leaving a good root bed for the spruce. In its new role as facilitator for private forestry, the Forestry Commission was only too pleased to license afforestation that helped to achieve its timber targets. The land was cheap and the planting grants generous. By 1987, the Perth-based Fountain Forestry company had bought up 40,000 hectares of land to sell on to its wealthy investors, earning them some £12 million by way of grants and tax exemption. The profits lay in public subsidies and early sale of the young forests to corporate investors, not in the crop; in effect the forests were financed by the taxpayer. Alexander Mather (1987) compared the new spruce forests of Scotland with banana and rubber plantations in the days of the Empire: decisions were taken far away, and local involvement and benefits were minimal. Even the contract labour was often imported. The forest companies failed to deliver their promises of jobs, an article of faith with credulous local councillors. For example, the much-publicised figure of 2,000 jobs in Caithness and Sutherland turned out to be a projection 50 years hence when trees were due for felling, assuming they survived that long. Until then, the true figure was closer to 60. Once planted, the trees needed minimal attention until harvesting. And to maintain even a modest labour force, there needed to be a continual supply of new land for planting. According to the National Audit Office, each ‘job’ created cost the taxpayer about £60,000.

Environment and amenity bodies were caught unawares by the speed in which aggressive forestry companies were buying up land. The only mechanism available to oppose damaging planting schemes was the SSSI, and even there the Forestry Commission was not bound to follow the NCC’s advice; in its response to the NCC’s report on afforestation, it explicitly rejected any idea that the FC should not promote afforestation on SSSIs. The 1970s saw some very contentious plantings, including the lower half of Abernethy Forest in Speyside and Llanbrynmair Moors in north Wales, both of SSSI quality. Things came to a head in the early 1980s at Creag Meagaidh (pronounced ‘meggy’), a mountain fastness north of Loch Laggan in the central Highlands. Creag Meagaidh was an SSSI, partly for the arctic-alpine flora of its montane grounds, including the magnificent north-east corrie, walled by 300-metre cliffs, but also for the natural mosaic of moor, marsh and birch wood on the open slopes below. Walkers and climbers were drawn there not only by its wild beauty, but because this was the one area in that part of Scotland which had not been rendered inaccessible by recent planting. In the early 1980s, the estate was sold to Fountain Forestry, who promptly slapped in an application to afforest practically all the slopes capable of supporting timber with Sitka spruce – some 1,100 hectares. The Forestry Commission dutifully offered a grant, the SSSI notwithstanding, and Fountain Forestry rejected the NCC’s subsequent offer of compensation for ‘forgoing profits’. The case went to the Secretary of State, George Younger, whose Solomonic judgement was to half the area covered by planting permission, and to urge the NCC to negotiate with Fountain Forestry over the remainder. Totting up their sums, the developers decided to abandon the project, refusing the NCC’s offer of a management agreement (‘voluntary agreements are doubly difficult in such circumstances because the tax advantages to an owner who wishes to afforest his land may outweigh any other consideration’, noted the NCC in its annual report). The NCC was left with no alternative but to assume responsibility for the whole 3,940-hectare estate. Creag Meagaidh was ‘declared’ a National Nature Reserve in May 1986. Having bought the land for £300,000, the company sold it to the NCC for £431,000, thanks to the added value brought to it by planting permission. Lucky investors.

Creag Meagaidh was only the opening skirmish in the struggle that culminated in the so-called Battle of the Bogs over the peat-flow country of Caithness and Sutherland, a series of flat, patterned bogs covering a vast, virtually uninhabited area in the far north of Scotland. This was a true wilderness, and made a great impression on any naturalist lucky enough to have seen it in its original state (see Plate 4). I vividly remember my own visit in the late 1970s, before afforestation had got underway. You could see for miles across countless lochans and colourful cushions of bog-moss to a still unobscured far horizon notched by the hills of Morven and Scaraben. At any step you might put up a greenshank, dunlin or golden plover; there were divers and scoter on some of the lochs, and the odd arctic skua or hen harrier hawking over the moss. There was a dreamlike sense about the place: the birds were different, the scale was Siberian; even the sky looked twice as big. Whatever small uses generations had made of it had left the flow country pretty much as they found it, wild, wobbly and weird.

Unfortunately, forestry technicians had discovered a way of growing trees on it through a combination of deep drains and the use of nurse crops on raised cultivation ridges, together with heavy doses of fertiliser and insecticides sprayed from the air. As at Creag Meagaidh, the tax and grant system allowed all concerned to make money out of the venture, including the flow-country laird who had at last found a buyer for previously almost worthless land. The Forestry Commission and Fountain Forestry targeted the area, and, by 1987, had bought up 65,000 hectares within it. The aim was a full 100,000 hectares, in a single vast estate that would achieve the hoped-for economies of scale. This would, of course, mean goodbye to the flow country of the bog-moss, greenshanks and the wide open skies, particularly as the physical and chemical effect of planting extended much further than the plantations themselves. The foresters offered to leave a few clearings for the birds, but, as Fountain Forestry’s director memorably observed, if the greenshank ‘cannot survive on 650 acres, it doesn’t bloody well deserve to survive’.

Since there had seemed no urgent need to do so, the area’s wildlife had never been surveyed in detail. It was only when, in response to gathering events, the NCC sent teams of peatland and bird experts to the Caithness flows that its full importance was recognised. To the bemusement of foresters and politicians alike, the NCC now claimed that the flow country represented ‘possibly the largest single expanse of blanket bog in the world’ (NCC 1987), containing significant proportions of the European Community’s nesting dunlin and golden plover and fully two-thirds of its greenshank (which was not all that many since the EC did not at that time include Sweden and Finland). The minister was reminded of the international treaties he had signed up to protect birds and bogs, including the EC’s directive on wild birds. The problem was that by the time all this was realised, afforestation was already under way.

The NCC ‘went public’ on the issue by publishing a glossy, full-colour report, Birds, Bogs and Forestry, summing up its scientific findings and pleading for a moratorium on further planting in the area pending a land-use strategy for the region. The Scottish establishment and media chose to regard this as an unwelcome intrusion in Scottish affairs, ‘without regard for the delicate economic and social fabric’ of the area. The NCC’s scientific claims were ‘preposterous’, said the local MP, Robert McClennan. The forests were a godsend and the NCC seemed bent on ‘sterilising’ the land, just like the Highland clearances of evil memory. In retrospect, the NCC might have done better to leave the high-profile campaigning to the RSPB, and concentrate on the assessment of the vegetation and bog structure it eventually produced, two years too late, in 1988. But the NCC’s chairman, William Wilkinson, had recently visited Galloway and the Borders, and had been appalled at the scale and impact of recent afforestation there. He now regarded upland afforestation as the most serious nature conservation issue of the past 30 years. Pressed by the NCC on the one hand and the formidable Scottish forestry lobby on the other, the Scottish minister made another Solomonic decision and invited the NCC to designate up to half the plantable area as SSSIs. Eventually this became the largest agglomeration of SSSIs in Britain. The immoderate publicity that followed Birds, Bogs and Forestry damaged the NCC’s reputation in Scotland. Moreover, it lacked the resources for designations on this scale, especially as they would involve potentially endless wrangles over compensation. The subsequent working party, convened ‘to examine land use options’ in Caithness and Sutherland, was chaired by Highland Regional Council, to whom jobs were generally the foremost issue. The noisy ‘Battle of the Bogs’ had at least exposed taxation-driven forestry investment for the disreputable racket it was. In the budget of 1988, the Chancellor (Nigel Lawson) stopped the gravy train dead in its tracks by removing the tax incentives for commercial woodland in one swoop, so that the expenses of planting and maintaining the new forests were no longer deductible. That effectively solved the problem at a stroke, but not before a lot of lasting damage had been done.

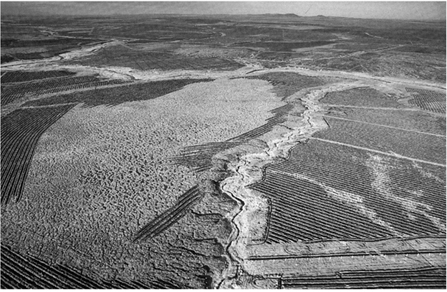

Financed by tax breaks. Planting trees in wet blanket bog requires deep drainage, plenty of fertiliser and sometimes a blitz of insecticides to combat pests, such as the pine beauty moth. The crop is barely economic. (Richard Lindsay)

In its place came the Woodland Grant Scheme (see below) and the Scottish system of ‘indicative forestry strategies’, regional plans for forestry which gave the local community more of a say. They came just too late to prevent more outrageous blanket plantations at Glen Dye in Deeside, at Lethem in the Borders, and at Strath Cuileannach in Sutherland, all grant-aided from the public purse, but, significantly, these attracted far more censure in Scotland than had much bigger schemes a decade earlier. In future, forestry in Scotland will have to take greater account of public opinion, and, as in England, will take on roles and guises other than timber production, such as public amenity and urban renewal.

Ancient woods and nature conservation

Most of our oldest woods are small woods. Except in the Fens, nearly every rural parish has at least one, their historic purpose being to supply timber to the owner and firewood to the parishioners. Some woods also supplied local trades with small-bore wood for making hurdles and fences, thatching spars and rustic tools. In iron-smelting districts, ‘colliers’ cut wood for baking into charcoal. Tanners relied on the bark of oak and alder to cure hides into leather, bakers on bundles of faggots to heat the ovens. Well into the twentieth century, a whole rural industry was kept supplied with locally grown wood through a traditional form of management known as coppicing, which capitalises on the fact that most British trees regenerate well from recently cut stumps (so long as deer and livestock are prevented from browsing them). Where timber was also wanted, generally for sale outside the parish, some trees, especially oak, were grown on as ‘standards’, and felled when about 70 to 100 years old. Judicious management preserved a layer of coppice shrubs beneath an open canopy of standard trees, linked by a system of open rides, with glades where the underwood had been cut recently. Such woods, shaped (but generally not planted) for purely utilitarian ends, formed our richest wild habitat. But, like most wild habitats that have been influenced by centuries of use, they demand maintenance. If too many deer get in, the system fails, as it also does when the wood is neglected, and allowed to grow too shady.

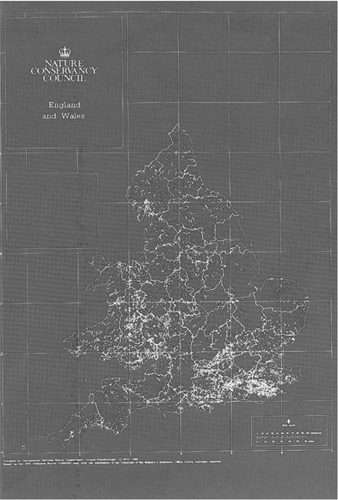

The pattern of ancient woodland in England and Wales is broadly the same as in the time of the Domesday Book, over 900 years ago – though the woods are smaller, fewer and often converted to timber crops. (English Nature)

It was not until the 1970s that, largely through the work of the NCC’s woodland scientist, George Peterken, the astonishing variety of natural woodland vegetation became understood. Peterken identified a dozen broad types of woodland dominated by different kinds of tree: oak, beech, lime, hornbeam, ash mixed with elm, ash mixed with lime, ash mixed with hazel and field maple. In a category of their own are the ancient pine woods of Scotland (see below). These are all semi-natural woods, in which most of the trees (beech and pedunculate oak are frequent exceptions), and the vegetation beneath them, are self-sown and wild. What many commentators failed to appreciate about our woods is that they can be exploited for all kinds of sustainable uses, and yet retain much of their natural character. Those which have existed for at least 400 years are known as ancient woods. Not all natural woods are ancient, nor are ancient woods necessarily natural. For example, much of the naturally regenerated woodland of Highland glens is of twentieth-century origin, while many ancient woods have been restocked with conifers and other planted trees. But a great many woods – generally the richest ones – are at least partly both ancient and natural. England and Wales have 397,700 hectares of ancient woodland, but most of the individual woods are small. The median size is 7 hectares in England and 5 hectares in Wales. Only 2 per cent of our ancient woods measure over 100 hectares (Peterken 1996). Ancient woods can be compared with parish churches, each one an individual, often with an ancient core on which later generations have added bits or removed them. You can often distinguish old woodland by ‘indicator species’. Tapestries of wood anemone, primrose and wood-violets are characteristic of ancient wood banks, and older woods have generally acquired a greater biodiversity, including scarce species such as wild service tree or wild daffodil. Woods rich in insects and other invertebrates generally contain a good deal of rotten wood, either in old standing trees or as stumps and fallen logs. Lichens and mosses also like old trees, along with moisture and clean air. Fungi, it seems, like undisturbed soil.

Coppiced ancient woodland at Brasenose Wood near Oxford with scattered oak and ash ‘standards’ over a layer of ash, hazel, birch and other trees cut on a regular cycle. Traditional management preserves ideal conditions for woodland flowers and sun-loving insects.

The twentieth century was not kind to our ancient woods. Two World Wars wrecked their timber value, but this was often rather marginal in any case. Worse, as rural economies ceased to need much wood, many woods were used as livestock shelters (‘barns with leaves’) or for rearing pheasants. Neglect changed their character from relatively open, flower-filled places to either a more shaded, damper environment less friendly to flowers and butterflies or an overgrazed, moribund scatter of trees. Between 1940 and 1980, about 10 per cent of all ancient woods were cleared away for farming, especially in the east of England. Many more were replanted. Until 1985, the Forestry Commission’s broad advice to woodland owners was to start again by cutting down most of the existing ‘scrub’ and planting crop trees, generally conifers with a leavening of oak and other hardwoods around the edge. It set an example on its own small wood properties. Oddly enough, ancient woods were often better protected in the suburbs, where they have been preserved for amenity, than on farms where they were just in the way.

Between 1984 and 1998, the Forestry Commission sold off 144,000 hectares of woodland, including many of its smaller properties. Many of them were restocked ancient woods of great character and importance to wildlife, and some were acquired by the Woodland Trust or by one of the county wildlife trusts. For example, the Worcestershire Wildlife Trust dug deep into its pockets to purchase Shrawley Wood and Tiddesley Wood, both replanted ancient woods in which some of the native vegetation had survived. Of Shrawley Wood, ‘half of which is supposed to be a conifer plantation’, Oliver Rackham (1990) could gleefully report that it was now once again ‘a magnificent lime coppice in which, in places, careful search reveals the remains of a conifer’. Happy as the restoration of such woods is, this was a classic instance of digging a hole and then filling it in again. We ought to preserve a few of those half-wrecked woods as a monument to the time when forestry meant getting rid of native trees.

In 1985, the Forestry Commission introduced its Woodland Grant Scheme, marking a dramatic shift from ‘coniferising’ to preserving native deciduous woods, especially ancient and natural woodland. For this reason it was important to identify exactly which woods were ancient. This became another of the NCC’s grand-scale surveys of the 1980s, undertaken mainly by contract workers under the supervision of Drs George Peterken and Keith Kirby of the NCC’s scientific team. Fortunately parts of Britain were well surveyed already, especially by Oliver Rackham of Cambridge University, the master of woodland ‘eco-history’. The NCC’s ‘county inventories’ of ancient woodland, with their tables and computer-generated maps, recorded relative size as well as distribution. They also provided a mass of information on the history and character of our woodland cleaves and dingles, hangers and copses, dumbles and ghylls, and the intricacy of their relationships with community and landscape. More than any other branch of ecology, woodland study has helped provide a temporal dimension to natural history, demonstrating the slow evolution of natural habitats over time. In ancient woodland you can feel the past, and sense the perpetual thread that runs through time, especially when you learn to read the clues.

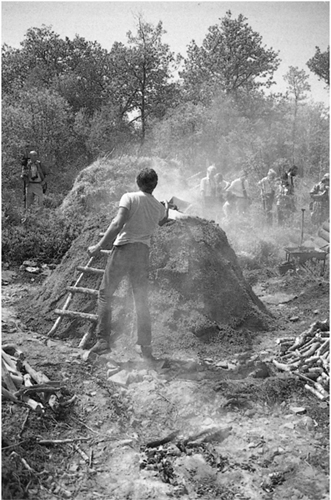

Since the 1980s, schemes that help to conserve and regenerate small woods have proliferated. Perhaps the most successful is the Woodland Trust (see Chapter 3), which has acquired hundreds of interesting woods and opened them to the public. Another welcome boost has been the resurgence of charcoal burning to provide a home-grown product for garden barbecues in a happy marriage of nature conservation and commercial harvest. Making quality charcoal requires the maintenance of a constant supply of coppice wood. At Bradbury Woods, Suffolk, one of the most celebrated ancient woods, a hard-working ‘collier’ doubles as the reserve’s de facto warden, while selling sacks of premium quality charcoal cut from the nature reserve. Contrary to popular belief, it is perfectly all right to chop down and chop up woodland trees, so long as it is done sustainably and so long as that has been the historic use of that particular wood. Most woods contain too many trees. Paradoxical as it may be for lovers of trees, most wildlife lives in the gaps inbetween.

Other locally based schemes aim to bring small woods into beneficial management by helping owners find markets for traditional woodland products, offering advice and organising training schemes. The basic idea is to promote small woods as things of value rather than ‘barns with leaves’. Coed Cymru, the Welsh Wildwood Campaign set up in 1985, a partnership of statutory and voluntary bodies, saves small woods from sheep by promoting regeneration and a more vigorous market for home-grown, low-grade hardwoods. For example, it has persuaded parts of the tourist industry to use Welsh oak instead of chemically treated softwoods for fence posts. Similarly, the Silvanus Trust in Devon ‘works to develop the viable and sustainable management of woods’ in south-west England through a crafts training scheme combined with market promotion of native woodland produce. Although the emphasis in both cases is on economic development, this can also a force for nature conservation by reinstating coppicing and related activities that diversify woods and benefit wildlife.

Making charcoal the traditional way by slow-cooking wood under a layer of turf. This demonstration was laid on to celebrate the 40th birthday of Yarner Wood NNR in 1992.

The Scottish pine woods

The native pine woods of Scotland stand apart from other natural woods in Britain. They used to be regarded as our least disturbed woods, their reputation as the last fragments of a vast ancient forest enhanced by their majestic mountain settings and the grandeur of the older trees. Their interiors, too, are quite unlike lowland broad-leaved woods (see Plate 6). In the place of familiar primroses and bluebells are heather, cowberry and blaeberry (the English bilberry) rooted in thick moss, or, in places, with a shaggy understorey of juniper bushes, some resembling clouds, others towering like cypress trees. Seedling pines need sunlight and mineral soils, and so these woods regenerate mainly in clearings created by felling or fire (which burns off the surface skin of peat), or around the edge. In their unenclosed moorland setting, natural pine woods are dynamic, changing their shape over the years, regenerating in one place and dying in another, expanding or contracting depending on the amount of grazing they receive. They have also been shaped by the interaction of natural events, namely storms and fire (being full of inflammable resin, pines are our least fireproof tree), and human usage such as timber management and stock grazing. On the lower slopes most of the pines are of planted origin, from seed collected from selected nearby trees. On the upper slopes, or the remotest part of the glen, decades of sheep and deer grazing has often brought regeneration to a halt, with the result that former woodland is turning into an open park landscape of moribund trees – beautiful to behold, but on the way out. The pine wood of Glen Falloch, which has seen no regeneration since 1820, now consists of only a scatter of elderly trees. Everywhere grazing has suppressed the natural tree line, except in a few special places such as Creag Fhiachlach in the Cairngorms.

Some 35 native pine woods were identified by the Aberdeen foresters Steven and Carlisle in their well-known book, The Native Pinewoods of Scotland, published in 1959. These were all Highland woods dominated by Scots pine, but native pine also survives as a component of lowland mixed woods and as fragments of original vegetation in plantations such as Glen More. A Forestry Commission survey in the early 1990s found in all some 16,000 hectares of native pine wood, including 3,500 hectares scattered in mixed woods and so overlooked by Steven and Carlisle. The largest area of some 4,700 hectares lies in Speyside, mainly in the great forests of Abernethy, Rothiemurchus and Glen Feshie, followed by 2,287 hectares in Deeside, concentrated in Ballochbuie, Glen Tanar and the southern Cairngorm glens. Other large pine woods lie in the east-running glens of Affric, Cannich and Strathfarrar, with smaller ones further west at Rannoch, Tyndrum, Loch Maree and elsewhere. We know better now than to regard them as fragments of a vast ‘Forest of Caledon’ supposedly destroyed by Vikings or Sassenachs. Pollen evidence shows that while many sites have been under pines for the past 10,000 years, the idea of a single vast forest is a myth (though that did not stop the Green Party from promising to recreate it in its Manifesto for the Highlands in 1989). In fact, Scotland has been poorly wooded for 3,000 years, and today’s native pine woods probably reached something like their present extent in the distant past. They are, in effect, ancient, semi-natural woods, like many of those in the lowlands. The difference is that the Scottish pine woods have long been recognised as special by foresters and conservationists alike. One of their first conservators was Queen Victoria, who saved Ballochbuie from the timberman’s axe by purchasing it in the 1850s. All but two of them are SSSIs – ironically, Ballochbuie is one of the exceptions; being personally owned by the Queen it is exempt from scheduling. Recently many have been Euro-designated as Natura 2000 sites, and native pine wood is also listed as a priority habitat in the Biodiversity Action Plan. Moreover they are home to many species listed in the BAP from red squirrels and capercaillies to obscure insects, spiders and lower plants known only by scientific names. Rothiemurchus alone has 16 BAP species (Smout & Lambert 1999).

A hen capercaillie on the nest. A catastrophic decline in this magnificent pine-wood bird may be due to a range of factors, including wet Junes and overgrazing of its favourite blaeberry (bilberry) plant. There is a voluntary ban on shooting, but the outlook is still grim. (John Young)

Even so, until the 1990s most of the larger native pine woods were essentially ‘working woods’, with timber production as their primary purpose. Back in the 1970s, the Forestry Commission and the NCC agreed on a scheme whereby the larger pine woods would be divided into zones for planting, using seed of local provenance, and for natural regeneration, with a further area set aside as natural non-interference forest. In practice, the plan was weighted towards forestry. In the ‘extraction zones’, management was close to normal commercial timber practice, while natural regeneration was speeded up by felling to create open clearings, in which the ground was often ‘screefed’ by bulldozers to expose the mineral soil, thus destroying the natural vegetation. Unless fenced, the non-interference zones, generally at the upper limits of the forest, became shelters for red deer and sheep, which put paid to any possibility of regeneration there. The scheme had the effect of eroding the natural character of the woods while doing little or nothing to prevent their gradual decay through overgrazing. It was thought more important to conserve the different ‘races’ of Scots pine, which are based on the chemistry of their terpene oils. Any seed used to replant native pine woods was supposed to be ‘of local provenance’, that is, from nearby natural trees.

The pendulum has now swung from timber production towards sustainable use and conservation. Since 1990, the FC’s ‘Caledonian Forest Reserve’ has been managed mainly for amenity and its environmental value rather than commercial production alone. Planting is still the policy, but the trees planted are Scots pine and other natives rather than the more commercially profitable Sitka spruce. The new policy was not without its opponents. Forestry and British Timber magazine, the mouthpiece of the industry, argued that ‘commercial conifer forestry has as much right to a place in the Cairngorms as elsewhere’. And as late as 1996, the FC granted Lord Strathnaver a felling licence to chop down some of his native pines. Today’s priority is to increase the area of native pine. Scotland’s forestry strategy aims at a 35 per cent expansion of the native pine wood resource by 2005, and 35 per cent more in the following 20 years. Along with that, there is a new emphasis on diversity. We now acknowledge there is more to pine woods than pine trees. Monocultures of Scots pine are an artefact of past management. Natural pine woods should contain boggy hollows and lochans, an admixture of pine, oak, ash and hazel along the lower slopes, and natural glades on rocky ground, or where flood, wind and fire has opened up the canopy. There is considerable current interest in restoring ‘wet woodland’ or muskeg, a habitat of scattered dwarf trees in a boggy glade that was scarcely recognised in the past – and so was often drained and planted. In 1998, the European Union funded a three-year project to restore some 300 hectares of wet woodland in waterlogged hollows and river valleys by blocking drains and removing exotic trees. If successful the project will help to enhance the natural biodiversity of pine woods, and also create a habitat of rare beauty and wilderness appeal.

Pine wood conservation is taking place amid the usual impenetrable blizzard of partnerships and acronyms. Behind the bland words, there still seems to be a rooted conviction that Scotland should look like Norway, and that absence of woods is tantamount to land degradation. In the Cairngorms the overall strategy is primarily the responsibility of the Cairngorms Partnership, destined to be replaced in a few years by a National Park. Here the situation has changed for the better since the bad old days not so long ago when the forest bogs of Loch Morlich were drained and planted, when half of Abernethy was chopped down, and visitors were about as welcome as harriers and stoats. Today the Cairngorms area is almost entirely in benign ownership, either by conservation bodies such as Scottish Natural Heritage, the RSPB and the National Trust for Scotland, or by enlightened estates such as Rothiemurchus and Glen Tanar. The Forestry Commission has joined in not only by grant-aiding woodland habitat restoration, but by restoring parts of its own estate at Glen More to a more natural condition, removing imported crop trees and planting local Scots pine. Elsewhere, the partnership is working towards a defined ‘desired future condition’ for each native pine wood, based not on some theoretical forest of the antediluvian past, but on the historic and natural character of that particular wood. The woods still provide timber, but it is to be harvested on a sustainable basis, and for a range of social purposes (it is still grants, not timber, that generate jobs). The Caledonian Partnership of conservation, amenity and forestry bodies has so far brought some 8,000 hectares of native woodland into ‘restorative management’, with the help of nearly £4 million of Euro-funding.

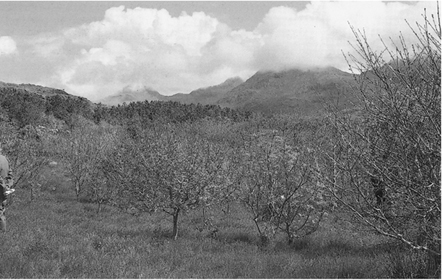

Rum’s new woodlands – an attempt to restore long-lost woodland by planting native trees. (Derek Ratcliffe)

Compared with the 1970s, the future of our native pine woods now looks fairly rosy, cherished as they are as a kind of symbol of Scottish wilderness and culture. Even so, expanding the resource does not necessarily guarantee the survival of its component pine-wood animals and plants. As a recent report by Plantlife has pointed out, the distinctive pine-wood flora, which includes rare and delicate species such as twinflower and one-flowered win-tergreen, has been entirely neglected (Coulthard & Scott 2001). Numbers of black grouse and capercaillie are dangerously low, thanks to the overgrazing of their favourite food plants by deer. The planting may help to fulfil targets, but it is creating plantations of Scots pine, not natural forest. A better nature conservation strategy would be to massacre the deer, fence the woods and then leave things to nature. But in a less than ideal world the attainment of a consensus that native pine woods are worth conserving is something.

Forest management for nature conservation

The idea of multi-purpose use came late to state forests in Britain. From 1949, the FC was allowed to consider the possibility of using forests for pleasure as well as profit. The following decade saw the establishment of National Forest Parks, the foresters’ contribution to access to the countryside, in which car parks, trails, picnic sites, holiday chalets and other attractions were designed. At first, however, there were few concessions to nature conservation. The Parks provided some long, shady walks with a fine view at the end, but as far as the trees were concerned, it was hard to spot any difference between, say, the Queen Elizabeth Forest (1953) or the Border Forest (1955) and any other large plantation. The past decade has seen real improvements. The advantage of public access is that it obliges forest owners to provide things the public likes, notably broad-leaved trees, watersides and glades, and they are good for wildlife too. There is, of course, a price to pay, in terms of badly sited car parks, trampling and disturbance, and the lopping of overhanging boughs and even whole trees as a safety measure. When the FC bought Hamsterley estate in Durham in 1927, the object was to plant as many conifers as possible. As its leaflet reminds us, ‘when foresters began planting at Hamsterley in the 1920s they were instructed to plant forests as strategic reserves in time of war. They did as they were told [my italics] and had to plant new forests with very little informed help, after all, people had been used to cutting down forests not planting new ones…How different things are today!’. Well, up to a point. To turn Hamsterley Forest into an amenity, Forest Enterprise planted more broad-leaves, removed conifers from certain beauty spots, and have started to create a more varied structure of fellings, mature stands and mixed woodlands. Meadows and unimproved pastures within the Forest (which the FC was not allowed to plant) have been designated SSSIs and the lower part of the Forest is now designated a Forest Nature Reserve. Some state-owned forests, such as Grizedale in Cumbria, have more elaborate facilities, including a forest centre, play areas and sculptures. The biggest of all, Kielder Forest, was beautified by amenity planting of birch and other trees after Kielder Reservoir was created, and has become popular as a kind of ‘English Scandinavia’.

Amenity use does not by itself serve nature conservation aims, but it usually implies some concessions in that direction. In large southern broad-leaved forests, such as Dean, Savernake and Alice Holt, the main problem is one of too many trees. Historically these areas were much more varied than today, with wood pastures grazed by cattle and ponies, and compartments cut over as coppice, as well as tall trees managed for timber. It was their structural complexity and, above all, their openness that made them so rich in wildlife. Forestry policy has either turned them all into similar kinds of high forest, or done away with native trees altogether, and replaced them with conifers. The foresters also felled most of the over-mature trees on the grounds that their timber value was deteriorating. This is rather like demolishing most of the chapels and ornaments of a church, while enlarging the nave into a single, plain, whitewashed hall. Wildlife thrives on detail, and detail thrives on variety. A single-minded policy of timber production produces a dull wood. The most notorious example of this triumph of profit over pleasure is the Crown inclosures of the New Forest, which were once famous for their butterflies. The replacement of the oaks and beeches with conifers in the 1960s reduced their interest considerably, but the coup de grace came in 1969 when the FC let livestock in, thus grazing the rides flat and eliminating nectar sources for the butterflies and the food plants of their caterpillars. It had banned butterfly collecting there in 1962, but there are now few butterflies in any case. The unenclosed ‘ancient and ornamental woods’ of the Forest were supposed to be managed as an amenity, not for timber. Unfortunately, foresters were convinced that these woods were not regenerating properly and needed a helping hand. This meant chopping down and removing many of the mature trees in operations that sometimes created awful mud baths out of the forest soil (as Colin Tubbs shows all too clearly in his book on the New Forest in this series). In 1970, the minister put a stop to it, but as late as 1996 there were still reports of old trees important for wildlife being felled in the Forest (the great winds of 1989 and 1991 blew down many more). By the 1990s, previous assumptions about ancient woodlands had been stood on their head. The ‘regeneration fellings’ are yesteryear’s policy and minimal intervention is now the fashion. The ancient and ornamental woods are assuming a more natural, most would say more attractive, character, with probably more dead wood than at any time in the Forest’s 1,000-year history. Coniferisation has been halted, but overgrazing remains a serious problem. Since 1982, the importance of the New Forest has been recognised by local authorities and by the Forest’s own administration. It is now, in effect, a National Park, and some of its woods are de facto nature reserves. With great care, and a lot of money, the New Forest may one day be nearly as good for wildlife as it was in 1950. ‘Old growth’ forest of the kind we were busy chopping down only a generation ago is now rare throughout Europe, even in Scandinavia, and the last remnants are cherished accordingly.

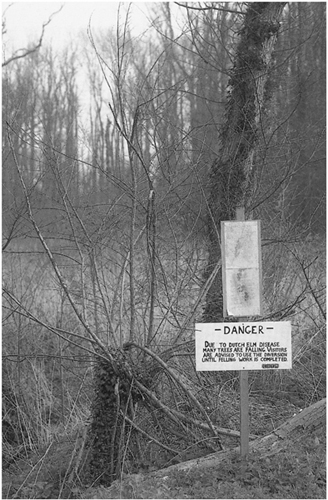

Only those with long memories or collections of old postcards remember how much Dutch elm disease changed the landscape. In the 1980s the woods of the east Midlands were full of dead elms, creaking and groaning spookily, like ghosts of the lost trees. This is Overhall Grove in Cambridgeshire.

Britain’s largest beetle, the stag beetle, is a ‘flagship’ species for the many insects that need dead and decaying wood. Yet there are more stag beetles in the hospital grounds and suburbs of South London than anywhere in the countryside – perhaps a reflection of the scarcity of suitable old trees in today’s woodlands. (Natural Image/ Bob Gibbons)

Today, woodland is arguably the best preserved natural habitat. Many woods are in a better state now than they were in the recent past, though some of the species they once supported have departed. Some are looked after by conservation bodies who now know more or less what to do – and, just as importantly, what not to do. In recent years the National Trust and some of the county wildlife trusts have made significant contributions to woodland management for conservation, especially in East Anglia, Nottinghamshire, Hereford and Worcester, Devon and North Wales. Public perception of what is good for woodland wildlife lags some way behind. At one extreme, people think no trees should be felled in nature reserves – but this would be disastrous. Our neglected woods are crying out for thinning and more openness. Regeneration, and much of woodland wildlife, thrives on sunshine, as every peasant and forester once knew. On the other hand, old trees are precious and more middle-aged trees should be left to grow old. Each veteran oak or table-sized ash stool took several hundred years to grow. Once gone, we cannot bring them back.

Forestry policy in England has become much more ‘people-friendly’. The FC’s new strategy, subtitled ‘a new focus for England’s woodlands’, swarms with colour pictures of children having the time of their lives, skipping along forest trails, snacking on straw bales and being enthralled by some puppet squirrels. By comparison, there is only one picture of a man sawing up a tree into planks. The minister, Elliot Morley, said he had ‘firmly closed the door on single-purpose plantations’. It is now conceded that not all places of value for conservation would be improved by planting trees, however well designed. Henceforth, forestry in England will have to pay court to national policies: rural regeneration, recreation (especially near cities), restoration of industrial wasteland and even nature conservation. This is described as ‘a flexible menu-based system allowing greater targeting to deliver public benefits from public money’. Behind the strategy lies an implied recognition that the glory days of coniferisation, in England at least, are over: the land is too well protected by National Parks, SSSIs and registered commons, and the go-it-alone conifer lobby has run out of friends. If commercial forestry has a future in Britain, it will be in Scotland.

It all looks like a remarkable turnabout. But is it? The propaganda is reassuring, but there is a suspicion that conservation projects are being used as a figleaf behind which, if not quite ‘business as usual’, a subtler form of afforestation continues. Large-scale plantings such as the National Forest in the English Midlands and the Millennium Forest in Scotland (see also p. 200) may have multi-purpose goals and respect open land of scientific interest, but they also assist forestry in its aim of growing as much timber as possible. Back in 1990, the Commission’s new director might have let the cat out of the bag in his remarks in Forestry and British Timber magazine: ‘The British public does not have a good feeling about Sitka plantations. It wants to see hardwoods so we have got to support these aspirations. I am not talking about a dramatic change in direction…We must support [the new forest in the Midlands] to enhance the public’s view of forestry: then we can get on with the job of planting timber’. And ‘planting timber’, Steve Tompkins has pointed out, still means draining moorland and planting Sitka spruce. At the end of 2001, the Forestry Commission completed a census of England’s trees. It seems there are now some 1,300 million trees, or 25 trees for every man, woman and child, covering 8.4 per cent of the land area. Though lower than the European average, this is still twice as many trees as there were a century ago, and probably more than at any time since the Middle Ages. The resurgence is entirely due to planting. The results were hailed uncritically by the press as a good thing for the environment. If so, it is a man-made environment, often produced at the expence of the natural one. The good news is rather that modern foresters are more ready to see trees as objects of delight, and not merely of profit. Some think the bad old days of commercial forestry are over. Time will tell. Perhaps the last word on this subject should be left to the man whose vision and patient persistence made much of this possible, George Peterken:

‘It is tempting to conclude that woodland nature conservation can now be safely left to the forestry profession, thereby releasing conservationists to devote their limited resources to less tractable problems elsewhere. In the short-term, this may seem reasonable enough, but in the longer term we have to recognise that pressures to cut back on nature conservation within forestry will periodically increase, and that Government policies can be altered to reinforce them. Many conservation organisations appear to have placed woodland conservation on the back burner, but this is unwise. In the long term, it would be prudent to maintain an active role for conservation organisations within forestry, for a strong, independent voice will periodically be needed to maintain environmental standards against other pressures on forestry.’ (Peterken 1996).