9 Development: Causes Célèbres

Wondering how to summarise the thousands of cases where development has come into conflict with nature conservation since 1970, I decided to choose just six, three in England, two in Wales and one in Scotland. You can learn more about conservation in practice from the detail of a long-running dispute than from any number of generalisations about procedures. My six examples raise basic questions about how we treat wild places. For example, the long-running soap story of the Newbury bypass focused attention on the nation’s road-building policies, and made people think about whether it is really in our interests to put road transport ahead of all other considerations. The case of Amberley Wild Brooks was similar to many others at the high tide of arable agriculture in the 1970s, but it was the one that settled an important issue: was agriculture always to have primacy over nature conservation? (answer: no). The periodic attempts to expand the skiing resort at Cairngorm raise wider questions about amenity and wilderness. In every case, the issues go beyond nature conservation in the narrow sense. But then, nature conservation is no longer defined narrowly, but as one of the defining principles by which we try to live. Cases such as these helped to make it so.

Amberley Wild Brooks

Jeremy Purseglove (Purseglove 1988) has written about the peculiar English attachment to landscape, which often finds its way into the stories that we loved as children. The river bank and the Wild Wood of The Wind in the Willows were based on real places (the Thames, near Pangbourne). So was the playground of Winnie-the-Pooh and Christopher Robin (Cotchford Farm in the Ashdown Forest), the chalklands of Watership Down (near Kingsclere, Hampshire), and the ancient mines and sandstone edges of Alan Garner’s novel, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (Alderley Edge in Cheshire). Even the chessboard fields in Through the Looking-Glass are said to have been inspired by Otmoor, near Lewis Carroll’s Oxford. As far as I know no such tales have been woven around Amberley Wild Brooks, a maze of dykes and wet pastureland on the flood plain of the River Arun in West Sussex, but all the same it is the sort of place that has bone-deep appeal – unexpected, secluded, a corner of wild cradled by downs and woods, overlooked by a ruined castle. Although covering only 360 hectares, Amberley Wild Brooks contains 400 species of flowering plants, including all the duckweeds, all the water-milfoils, 35 kinds of grass and practically every pondweed known from south-east England. Birdwatchers came there to see the flocks of Bewick’s swans that arrive in winter from Siberia, bringing, as Purseglove describes it, ‘an improbable flavour of the Russian steppe to the domesticated landscape of the Home Counties’.

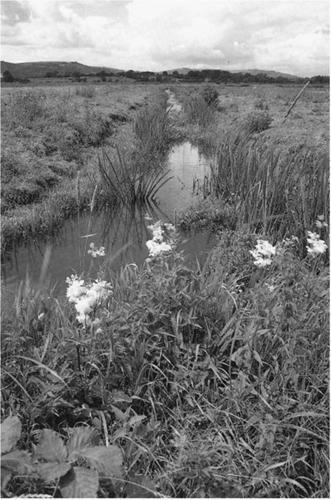

Amberley Wild Brooks. The grassland is rather ordinary – which is why the extraordinary quality of the place was overlooked until the 1970s. Its secrets lie beneath the water. (Natural Image/Bob Gibbons)

Most of these plants and animals survive there for one reason above all: Amberley Wild Brooks is wet, and the water is clean and clear. In the rainy winter of 1974-75 it was very wet. Since the War, and particularly since Britain’s entry into the Common Market in 1973, agricultural policy had attempted, as far as possible, to ‘tame the flood’ in order to grow more food. Improved drainage technology enabled a water authority to pump practically any wetland dry enough to grow barley, so long as the taxpayer footed the bill. And so they did, on a broad scale, heedless of the environmental cost. In the case of Amberley Wild Brooks, local farmers wanted to drain the flood plain to build up their livestock grazing, which would in turn free them to plough the nearby downs for growing more cereals. Acting on local complaints about the wet fields, Southern Water Authority, keen to oblige, prepared a suitable plan and applied to the Ministry of Agriculture for £340,000 under the recent 1976 Land Drainage Act. Amberley Wild Brooks was not at that time a protected site, and that would normally have been that: more cows and no pondweeds. However, this was Sussex, full of well-heeled, middle-class, weekend countrymen, steeped in the culture of Beatrix Potter and Kenneth Grahame. They complained, as did conservation bodies such as the CPRE and the RSPB. For this exceptional case, the minister called in the application and a public inquiry was held in March 1978.

The conservationists won the argument. Unusually, they had been given access to the figures – a serious mistake as it turned out – which enabled the economist, John Bowers, to show that, even leaving the environment issue aside, Southern Water Authority had overstated the benefits. Since society was paying the bill, he argued, there should be some return to society. Here, who gained but the farmers? What do people want – more cows or natural beauty? As Norman Moore, the NCC’s Chief Advisory Officer and main witness, cogently argued, Amberley Wild Brooks was a test case: ‘if conservation is not paramount in this case, no site can be considered safe’. If one of the richest wetland sites in the country, home to numerous rare plants and animals, could be drained with public funds, then conservationists might as well give up. The inspector upheld such arguments, and grant-aid was not forthcoming. Instead, the NCC held ‘valuable and constructive’ meetings with all parties for an alternative scheme that would leave room for some agricultural improvements without spoiling its special character (for at that time even conflicts won produced compromise agreements).

Amberley Wild Brooks was a test case that established a precedent: henceforth agricultural improvements would not have an automatic priority over wildlife. Others, not just the local land users, would have a say in what happened there. The sense of a turning point being reached was reinforced a few years later when the Inspector ruled against the reclamation of Gedney Drove End, an SSSI on The Wash, for much the same reasons. The agricultural lobby was a sore loser. In future, the water authorities and the Ministry of Agriculture would be more guarded about revealing their cost-benefit figures. At least one Amberley farmer said he would stop naturalists visiting his land. And even here, the drainage had been improved before the rumpus of 1978, and there were fewer and fewer wild duck and swans roosting in the winter-wet fields below the ruined castle. But such was the power of the agricultural lobby in those heady days that Amberley Wild Brooks was regarded as a victory for the little green David against the Goliath of the CAP. There was still hope for wildness and wet.

‘The Third Battle of Newbury’

Between the county library and the local museum in Newbury is a gallery and coffee shop called Desmoulins, named in honour of a tiny but now famous snail called Vertigo moulinsiana, the Desmoulin’s whorl snail. Everybody in Newbury knows about ‘the snail that nearly stopped the bypass’. It has become a symbol of the environmental price we pay to get from A to B that bit faster. Judging from recent cases in the media, small, rare animals seem to make a habit of living in the path of bypasses. In the case of the Dersingham bypass in Norfolk it was a moth, Choristoneura lafauryana, about the size of a fingernail and ironically christened the ‘mighty moth’ by the tabloids (‘Bypass Mothballed’). For the Winchester bypass at Twyford Down the best they could come up with was a colony of the chalkhill blue butterfly, although one that was said to be the largest in Britain. But with Newbury, obscurity returned in triumph with a snail the size of a breadcrumb that the European Union in its wisdom was about to list, along with its habitat, as endangered. It meant that the British government could in theory be taken to court if it heedlessly squashed the snail in its haste to complete a fast highway from the port of Southampton to the industrial Midlands.

The Newbury bypass, built amid scenes of considerable turbulence in the mid-1990s, follows a route west of the town through some of the loveliest countryside in the Thames valley. This was the route the Department of Transport had wanted, and the one the Inspector recommended after a public inquiry held in 1988. Because Newbury sits in a valley surrounded by woods, heaths and marshes, any road bypassing the town was bound to conflict with wildlife and amenity interests. At the 1988 inquiry, the NCC gave evidence on the impact on wildlife of alternative western and eastern routes. Both would cause damage, but the NCC was more opposed to the grottier route east of the town since it would cross an established SSSI and Local Nature Reserve at Thatcham Reedbeds. The western route, though passing through beautiful countryside, threatened fewer protected sites: a corner off Snelsmore Common SSSI, a local trust reserve at Rack Marsh and a couple of non-statutory ancient woods. This route was defended mainly by local residents (SPEWBY – the Society for the Prevention of the Western Bypass) – although the NCC did have reservations about the way the Department intended to cross the Rivers Kennet and Lambourn, by embankment rather than a less environmentally damaging bridge. No full impact assessment was ever made, and the presence of otters, dormice, badgers and other protected animals along the western bypass route was overlooked or underplayed. Had the Countryside Commission joined forces with the NCC, it might have been different: the Commission was more concerned about scenic beauty than the NCC. Unfortunately, for reasons of its own it decided not to become involved. At a subsequent public inquiry, held four years later in 1992, the Inspector refused to reopen matters, such as wildlife, that he said had been covered four years earlier. Two years after that, the Secretary of State for Transport, Bruce Mawhinney, deferred his final decision on the bypass pending a review, then changed his mind and gave the go-ahead in June 1994.

Shortly before the road engineers moved in, someone found colonies of the Euro-listed Desmoulin’s whorl-snail living in the river marshes directly in the path of the road. This meant that the marshes might qualify as a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) under European legislation, which gave those opposed to the bypass the basis for a legal challenge. And many were opposed (although the residents of Newbury, sick of traffic congestion, were mostly for it). Shortly before roadworks began in the winter of 1995-96, a petition signed by 10,000 people was handed in. About half that number walked in quiet protest along part of the route. Professional protesters moved in, mostly young people who camped in the woods and, to make it harder to evict them, built tree houses, tunnels and aerial walkways. Visiting the camps, there was a strong sense that the environment had become a new religion. Cabalistic totems – feathers, stones and bones – were tied to trees1. Many of the protesters were vegetarians. ‘Look over there,’ said my guide, as I left my goodwill gifts of whisky and cake. A small group crouched around a fire were seemingly segregated from the others. ‘Do you know who they are?’ she asked. No, I didn’t, but suspected they might be some sort of secret weapon. ‘They are…the meat-eaters’. She made them sound like cannibals.

Thanks to the protesters, the Newbury bypass became the most expensive non-tunnel 14 kilometres of road ever built in Britain. Some 500 security guards were hired to protect the workforce and evict the protesters from their camps. Television reported every stage, and an archetypal protester called Swampy became a national hero. As a tactic, conservationists led by Friends of the Earth decided to champion the snail. The protesters at the aptly named ‘Ricketty Camp’ on Speen Moor tried to avoid eviction by claiming that they were protecting a species against illegal persecution. Their case was taken to the High Court in March 1996, but failed since, in the judge’s view, claiming to protect the snail was no excuse for illegal occupation. He did, however, urge the Government to try to minimise the damage to Desmoulin’s Snail and its watery home. The Environment Secretary, John Gummer, responded by proposing eight isolated colonies of the snail as a kind of polka dot candidate SAC that left plenty of room for a dual carriageway. After 15 years of argument, the Government was determined to have it built.

A coalition of conservationists fronted by Friends of the Earth and WWF-UK returned to the High Court to seek leave for a judicial review of the Highway Agency’s treatment of Gummer’s proposed SAC. The judge’s refusal this time seemed rather technical. The snail sites were not a candidate SAC, he ruled, but only a possible SAC. However, as before, Mr Justice Sedley tempered his judgement with remarks that were helpful in the long run. By pressing ahead with the road at the same time as it was going out to consultation over its environmental impact, ‘the Government is apparently foreclosing the possible answers to its own question’. He went on, ‘One can appreciate the force of the view that if the protection of the natural environment keeps coming second, we shall end by destroying our own habitat’.

The snail story now moves into realms of farce. The Environment Agency in consultation with English Nature came up with a plan to move the snail out of harm’s way, along with chunks of its habitat, by digging up giant turves and transporting them to a prepared site further upstream. It did not seem to matter that no one knew anything about the snail’s life cycle or ecology, nor that the silly little snail was obviously being used as a means to an end, not as the end in itself. Besides, even on its own terms, digging up turves in the hope of saving an obscure snail was probably a waste of time. As the snail expert at the Natural History Museum warned, ‘to think you can sustainably recreate a complex ecosystem that has taken centuries to develop in the space of a month does not make biological sense’.

To cut a long story short, the Newbury bypass was built. It opened without ceremony in November 1998. In the meantime, the junior Transport Minister responsible, Steven Norris, appeared on television to admit he had since changed his mind and agreed that always ‘pandering to motorists’ at the expense of the environment was wrong. The fuss over the Newbury bypass had undoubtedly convinced many in Government that its roads policy was unpopular and becoming a serious burden on public expenses. The fact of the matter was that while protests could not physically prevent a road from being built, they could delay the process until Government was tearing its collective hair in frustration and dismay at the growing cost. At nearly £6 billion in 1994-95, Transport had become Britain’s third-largest spending department, with a budget twice as large as Agriculture and three times that of Environment. The proposed link road through Oxleas Wood in Greater London, which was, in the end, not built, involved eight years of public wrangling; the Winchester bypass at Twyford Down, which was, took another eight. Potentially the next set of damaging headlines would be the new bypass at Salisbury, involving damage to Harnham Meadows, an SSSI and another prospective SAC. In the Government’s subsequent U-turn on roads, this road, and dozens of others, was put on hold or scrapped. [By 2001 there were signs that Government was changing its mind again, approving a long list of new roads, such as the previously cancelled Birmingham Northern Relief Road.]

Today one of the prettiest corners of Berkshire has been irredeemably spoiled. On the other hand, Desmoulin’s little snail is not doing too badly; indeed it is now known to be widespread by chalk streams in the south of England. It even has its own leaflet, published by English Nature, flying the flag for threatened snails everywhere. It would be interesting, though, to learn how it managed to find its way into Annex II of the mighty EU Habitats Directive, and why no one bothered to investigate its status in Britain first. I was less than surprised – and not terribly pleased either – when a conchologist friend found what he suspected to be Vertigo moulinsiana in a sedge bed a few yards from my home in the Kennet valley. But I suppose it may come in useful one day, should government decide to build a bypass through the back garden.

The Berwyn saga

Y Berwyn, the Berwyn mountains, lie in an underpopulated corner of Wales on the borders of Denbighshire and Powys. They form a rolling plateau swelling to 827 metres (2,713 feet) at Moel Sych, with heather on the lower slopes grading upwards into natural grassland with blanket bogs along the watersheds. In times gone by, the area was managed as grouse moor, but over the past half-century grouse numbers have plummeted. Today the Welsh red grouse is not so much a sport species as an endangered one. In 1957, the Nature Conservancy designated 3,900 hectares around Moel Sych a Site of Special Scientific Interest, as a good example of moorland and bog, noted for its bird life, especially breeding raptors, such as merlin and hen harrier, and waders, such as golden plover. But most of this 62,000-hectare range of hills was protected only by its inaccessibility and naturally infertile soil.

A view of the Berwyn plateau, now part of a National Nature Reserve. (CCW)

By the 1970s, agricultural subsidies were making the Welsh hills more profitable by increasing the sheep stockage with the help of drainage schemes and heavy doses of fertiliser. Forestry companies were also interested in this part of Wales, which had largely escaped the blanket afforestation of so many former sheep-walks and grouse moors elsewhere. Knowing what was in store, in 1977 the RSPB surveyed the bird life of the Berwyns and found it to be even more important than had been thought. Some 60,000 hectares, in several large blocks, qualified as SSSI, said the RSPB, and the NCC should fight hard to preserve them. However, the NCC felt that notifying so large an area would injure relations with the local farming community. Its director for Wales, Dr Tom Pritchard, decided that a softer approach was necessary. The NCC had a statutory duty ‘to take account of other land uses’, but as he wrote in the NCC’s Annual Report, ‘success in nature conservation is more often achieved by understanding and goodwill in the field than by legislation and compulsion’.

Normally the decision to notify an SSSI would be taken purely on scientific grounds. In this case, because of the sensitivities involved, the NCC decided first to consult the Welsh Office, the Agricultural Development and Advisory Service (ADAS) and the Forestry Commission. Their firm and unanimous view was that the economic development of the area was more important than wildlife. The NCC looked for a way out of the dilemma. It decided to commission Reggie Lofthouse, formerly Chief Surveyor at ADAS, as an independent arbiter. Lofthouse came up with an alternative scheme that effectively shared out the cake among the interested parties. In addition to the SSSI there would be informal ‘consultation zones’ where any publicly funded developments likely to damage the scientific interest would be ‘scrutinised’. The NCC appointed a full-time official for the Berwyns, whose job was to build bridges and negotiate agreements with the dozens of owners and occupiers in the area. Disgusted with this performance, the RSPB threatened to take the NCC to court on the grounds that it had not fulfilled its statutory duty to notify the entire area of scientific interest (it eventually desisted, having noted NCC’s more robust stance on West Sedgemoor in the Somerset Levels). The Welsh Office, on the other hand, applauded this ‘most valuable fresh approach’. The undersecretary, Michael Roberts, hoped that the solution hammered out in the Berwyns would spawn similar initiatives to reconcile nature conservation with agricultural and forestry interests. In 1980, some 70 local owners and occupiers formed a Berwyn Society to represent their interests and oppose further SSSIs in the area.

Meanwhile the waters were muddied further by an afforestation plan that left very little room indeed for compromise. In 1979, the Economic Forestry Group (EFG) acquired another hill area in the Berwyn, also of SSSI quality, called Llanbrynmair Moors. This contained a particularly high density of breeding birds, as well as one of the best peat bogs in Wales. The EFG wanted to plant up all 1,800 hectares of it. After some hesitation, the NCC decided not to oppose the plan, apparently as part of an arrangement with the Forestry Commission. It also turned down an offer to sell the site due to ‘the pressure of other priority cases on [its] limited finances’. All the NCC could win by way of mitigation was EFG’s agreement to leave certain small areas unplanted. The rest was drained and planted, with the help of a £400,000 grant. Commenting in Birds magazine, the RSPB’s director Ian Prestt contrasted ‘the vigour and determination with which forestry interests pursue their objectives’, with ‘the relative weakness and uncertainty of the NCC’s attempts to defend important ornithological sites’. Plainly, he saw the NCC’s actions as evidence of a worrying lack of confidence.

The problem with the conciliatory approach exemplified at the Berwyns is that nature conservation has to play second fiddle to more powerful interests. The Forestry Commission’s views about the extent of plantable land in the Berwyns were never questioned, nor did the NCC take issue with the agricultural assessment. The NCC’s proposals, on the other hand, were put under the microscope, and whittled down bit by bit. ‘Whatever the outcome,’ wrote John Sheail commenting on the case, ‘it was a sign of weakness to be always responding to the demands and criticisms made by others’ (Sheail 1998). Bill Adams considered that for all the fine talk about ‘co-operation and integration’, the Berwyn experience was one of retreat and defeat’ (Adams 1986). In defence of the Welsh NCC’s position, its powers were weak and the local hostility to SSSIs was great. All that its statutory role won was a place at the negotiating table, where the NCC was heavily outgunned. Tom Pritchard was convinced that his conciliatory tactics lay within the spirit of the law, and that he had achieved all that could realistically have been expected.

Today part of the Berwyns is a National Nature Reserve, the NCC and its successor body having bought out farms and tenancies as they came on the market to save them from afforestation, while doing their best to offer grazing and estate work to those still doggedly farming on. The end of tax benefits for forestry in 1989 brought a respite, and ironically some of the trees planted in the 1970s are now being removed (also with public money, needless to say). With the benefit of hindsight, the future of hill areas such as the Berwyns might be better served by inclusive schemes that recognise the primacy of sustainable use. The Berwyns saga is a monument to how things were done 30 years ago, and why nature was the constant loser.

Tidal barrages and Cardiff Bay

Judging from the statistics of ‘loss and damage’ trotted out annually by the conservation agencies, while it is easy to damage a Site of Special Scientific Interest (for example, by simply neglecting it), it takes a great effort to destroy one. Even after the land has been drained, fertilised and reseeded, there is usually something left, stubborn remnants of wild habitat that still justify an SSSI label. The instances where an SSSI has been completely obliterated, such as Herald Way near Coventry (drained and then built on) or Selar Farm in South Wales (it became an opencast coal mine), are few enough to be individually notorious. The best-known example of all is the Taff-Ely Estuary SSSI, also in South Wales, whose once teeming mudflats and tidal marshes are now permanently under water. It is better known as Cardiff Bay.

Tidal barrages have three main purposes. In the 1970s feasibility studies were carried out for barrages at the Morecambe Bay and The Wash that would act as impoundment reservoirs of fresh water. In the event, Government opted to build inland reservoirs instead, at Kielder in the Borders and Rutland Water in the Midlands. The second purpose of a barrage is to create tidal energy. Alternative sources of energy began to be explored seriously in the 1980s, when oil and gas prices were high, and when enthusiasm for nuclear power was falling, especially after the Chernobyl disaster and embarrassing rumours of leaks at Sellafield. Two major barrage schemes, on the Mersey and on the Severn, were investigated. Plans for a barrage on the Usk were eventually turned down after a public inquiry in 1995, largely on environmental grounds, but there are current proposals for barrages on the Loughor and Neath estuaries, as well as the giant, though presently mothballed, scheme for a Severn barrage. Which brings us to the third reason why authorities like barrage schemes - amenity and urban regeneration. This is most evident in South Wales with its decayed towns and narrow estuaries. A barrage on the Tawe was constructed between 1989 and 1992 as part of a plan to restore the Lower Swansea valley. And the local authorities had long wanted to build a barrage at Cardiff.

‘Unsightly mud’. Cardiff Bay before the barrage. (Niall Burton/BTO)

The main environmental problem of tidal barrages is that they reduce valuable natural habitats by drastically constricting the tidal range (that on the Tawe fell from 10 metres to 1.5 metres). They also change the character of an estuary by removing the daily scour of the tide and replacing intertidal habitats with a lagoon vulnerable to pollution from sewage and toxic metals brought in by the river. Unfortunately there is no national policy for estuaries, and so they are subject to piecemeal development that slowly diminishes their value for wildlife. At present, the economics for tidal barrages are less favourable than they once seemed, but all it may need to revive them is a rise in fuel prices, while summer droughts might also revive proposals for impoundment reservoirs.

The barrage proposed for Cardiff Bay generates no energy at all. Its role is entirely one of amenity. The City of Cardiff is formed around a bay into which two rivers, the Taff and the Ely, converge, depositing their loads of silt from the valleys inland as mud banks. These are exposed at low tide when, particularly in winter, they become one of the densest feeding grounds for waders and wildfowl in the Severn estuary. Enough dunlin, shelduck, curlew and redshank used the bay for it to have been designated as an SSSI and proposed as a Special Protection Area for wild birds. Unfortunately, mudflats are rarely seen by urban planners as an especially attractive asset. Cardiff had a down-at-heel appearance not in keeping with its dignity as the capital of Wales. In 1987, the Welsh Office and the local council came up with plans for a major redevelopment programme of the dockland area, which included covering up the unsightly mud with water to provide an attractive inland bay. This would be done by building a massive 800-metre steel and concrete embankment, paid for largely by the taxpayer. Delighted with the shimmering yacht-filled lake in front of them, developers would, it was hoped, flock to Cardiff.

Knowing that conservation bodies would object strongly to the destruction of an SSSI, the then Welsh Secretary, Peter Walker, met the NCC’s chairman in 1986 to explain his plans and seek the NCC’s co-operation in mitigating the ecological impact of the barrage. An expert on waders, John Goss-Custard, was commissioned to investigate its probable ecological consequences, and to propose substitute feeding grounds for the displaced birds. He made several suggestions: the barrage gates could be adjusted to provide some intertidal habitat in winter. Alternatively new tidal flats could be recreated nearby, or mudflats recreated over a wider area by the eradication of cord-grass. The idea that found most favour was the substitution of equivalent wildlife habitats nearby. A suitable site was found on part of the Gwent Levels at Wentloog, near Newport (ironically, as this was itself a proposed SSSI, as coastal marshland, the creation of lagoons and mudflats would involve ‘damaging’ it!). Conservationists complained that the this new site could accommodate only a fraction of the birds that used the Taff estuary, even if they were adaptable enough to exploit the opportunity.

By being allowed to present a private Bill to Parliament the developers found a way of circumventing the normal planning process. The decision would be made not by local representatives or after a public inquiry, but by a Parliamentary committee, to which petition could be made. Some 69 bodies, including the NCC and the RSPB, presented objections, centred on the inadequacy of the proposed substitute habitat and casting doubt on whether the lagoon behind the barrage would be as pure and shimmering as the developers projected it. On the contrary, without expensive artificial oxygenation, it could easily become a stagnant, midge-infested pond (they claimed). There was also the small matter of its international status as part of the Severn estuary, a potential SAC, which could involve (and the voluntary bodies would do their best to ensure it did involve) the European Commission.

The Barrage Bill was eventually passed in 1991. Full details of the habitat compensation scheme were not announced until 1996, when the Government unveiled its plans for a £5 million, 375-hectare nature reserve on the grounds of a former power station between Uskmouth and Goldcliff on the Gwent Levels. Saline lagoons and reed beds would be created by the dextrous use of pumps and artificial embankments. However, welcome as these are, it can hardly be regarded as habitat replacement since it is food-rich intertidal mud, not reeds and lakes, that has been lost. The Gwent Levels is in any case too far from Cardiff for site-faithful birds such as redshank to take advantage of it. In the meantime, conservation bodies led by the RSPB, WWF-UK and Friends of the Earth brought their case to the European Commission on the grounds that Cardiff Bay qualified as both an SPA and an SAC. They claimed that the developers’ formal Environment Statement was flawed in that it failed to evaluate the ecological impact in terms of the actual numbers of birds that would have to find new feeding grounds. However, the Commissioner found ‘no lawful impediment to the scheme’, insisting that ‘substitute habitat’ was being created side by side with the construction of the barrage. That view seemed dubious after the Lappel Bank case in 1996, in which the EC ruled that it was unlawful to exclude an area from SPA designation on economic grounds.

Work on the barrage across the mouth of the bay began in 1993 and was completed on 4 November 1999. In the interest of the birds, it had been hoped that the Development Corporation would leave its gates open, and allow the tide to take its course for one last winter season. The Corporation thought otherwise, and the gates promptly slammed shut. The event was televised, amid scenes of confusion suggesting that the operators were still a little uncertain about how it all worked. Ultimately the enclosed bay will fill up with fresh water.

Cardiff Bay is the most prominent example of habitat substitution, a popular tactic used by developers in the 1990s, and one which the conservation agencies often went along with. It enables developers to honour their environmental obligations to the letter, but involves considerable risk to wildlife. It is too soon to form any definite conclusion about the fate of the birds of Cardiff Bay. Certainly the bay is now useless for wading birds except as a limited high-tide roost. Studies by the BTO using colour-ringed birds indicate that the redshanks have moved to the nearest estuary, that of the small River Rumney a few kilometres east of Cardiff (Burton 2001). Curlew and oystercatchers have also dispersed along the coast. Competition for limited food and space is likely to increase, but it is too soon to tell whether this will affect the survival rate of the displaced birds – though it is probable. In the meantime, the Severn estuary has been declared a Special Protection Area (SPA) by the European Union. Any future development will have to be judged by its impact on the estuary as a whole.

Against the odds: the case of Rainham Marshes

Wildlife protection and urban regeneration make uneasy bed-mates. Perhaps every expanding town has at least one major clash, from the housing estate and link road built on Aberdeen’s best wildlife site, Scotstown Muir, to the unfortunate newts of Peterborough and the shrinking intertidal mudflats of Teesside. The struggle to preserve wild open spaces in Greater London is a story in itself, but in the 1990s one of them dominated the headlines: the long-running saga of Rainham Marshes.

The ‘grazing marshes’ of the Thames estuary, immortalised in novels such as Great Expectations, once extended from the Isle of Sheppey to the Isle of Dogs and beyond into Essex. Over three-quarters of it was drained or developed during the twentieth century, and the section on the north bank between Rainham and Purfleet in the London Borough of Havering now marks the last wild wetland within London. In 1986, the NCC scheduled 480 hectares of it as the Inner Thames Marshes SSSI, the largest in the London area. The main ditches form breeding grounds for water vole and a variety of insects, including the scarce emerald damselfly. Lagoons have formed where silt from the river has been dumped and here teal gather to feast on sea-aster seeds. Hen harriers and short-eared owls hawk overhead searching for voles and mice, and botanists can still find some of the special plants of brackish grazing marsh, such as divided sedge and brackish water-crowfoot. All the same, Rainham Marshes had a battered, unkempt look. Standing near the huge landfill site that marks its western boundary, breathing in the fumes from nearby industries, you gazed on an unloved landscape of fly tips and illicit camps, unknown fluids leaking from rusty drums, overhead wires and muddy scars left by motorbikes. Bad things happen there. An ecological surveyor found a man’s body, hog-tied and shot through the head. Police are sometimes seen poking the undergrowth with sticks. Even the NCC’s own director had his doubts: ‘is this SSSI?’ were his incredulous words. Wildlife often thrives in grotty areas, but Rainham Marshes had been allowed to become much too dry, and much of it has not been grazed for years, apart from the odd itinerant peddlar’s horse. The far end, at Wennington and Aveley Marshes, is in better condition since it was looked after by the Ministry of Defence which had a rifle range there. But it, too, is drying out. Most local residents were sceptical about its conservation value. Conserving the oceans and rainforests was all very well, but, as Bill Adams (1996) noted, ‘when the issues were really in their own back yard, people became critical of the ideological freight train of conservation rhetoric, as indeed they did of the glossy portfolio of the developers’.

‘Is this SSSI?’ Rainham Marshes: an object lesson in our treatment of wilderness. This part is reinstated marshland, following a court order. (English Nature/Peter Wakely)

The developers were numerous, but one stood out from the rest: MCA, the Music Corporation of America, were interested in the site for a huge development involving a theme park, film studios, shops, offices and 2,000 homes. At £2.3 billion, it would have represented the second largest ever foreign investment in Britain, and provide a claimed 30,000 jobs. MCA were able to exploit a bizarre loophole in the planning system following the abolition of the GLC and the consequent suspension of the development plan for Greater London (which had protected the site). Havering Borough Council gave the MCA an unusually open-ended planning permission with no time limit. The Secretary of State decided not to call it in for a public inquiry even though the development would have led to the greatest loss of an SSSI to development since the Wildlife and Countryside Act was passed in 1982.

MCA offered conservationists a mitigation package of unprecedented size. In Britain such compensation is normally grudging and minimal, offered on an acre for acre, tree for tree basis. In this case, £16 million was eventually on the table, representing half of the NCC’s entire annual budget, more than enough, theoretically, to buy and manage every grazing marsh in the Thames estuary. To its credit, the NCC did not grab the ‘blood money’ and run but maintained its objection. As it turned out, the theme park and the film studios were never built, and so the cash offer was illusory. At the end of 1990, MCA was bought by a Japanese company and sold on to a Canadian one. Five years on, it was revealed that the theme park, complete with dinosaurs, was to be built not in London after all, but in Japan.

After MCA disappeared from the scene, the site continued to degrade. The A13 road was re-routed across the edge of the marshes, and, contrary to assurances given at the public inquiry, spoil was dumped within the SSSI. Parliament allowed the construction of the Channel Tunnel rail link, complete with marshalling yards, across the site. English Partnerships, the urban regeneration quango, won itself outline permission for an industrial complex on the site, despite its stated belief that open spaces are ‘important contributors to the process of regeneration’. The case looked hopeless.

Then something happened. In 1990, local opinion had been in favour of developing the marshes, then regarded as a lawless wasteland. It suited developers to keep it that way. All the same, a few realised that the place was not without its redeeming merits, which could, with suitable investment and care, be turned into an asset. Its growing band of supporters formed the ‘Friends of Rainham Marshes’. Public opinion was changing. When the MoD decided to withdraw from its part of the marsh, some local residents, without waiting for permission, blocked some of the main drains and flooded the site. Very quickly it was thronged with birds, demonstrating that, given the right management, there was still life in the marshes. A few years on, the RSPB acquired the eastern end of the SSSI with the help of a half-million pound private donation via the landfill tax credit scheme, and entered into an agreement with the Port of London Authority for the sustainable management of the silt lagoons. It is now controlling water levels to create shallow pools, ditches and wet grassland, and starting on the huge task of clearing unexploded ammunition. Soon it hopes to open the marshes to the public and build an education centre there. The western end of the SSSI, at Havering Marsh, remains derelict and could still be developed. But, given the sea change in public opinion since 1990, and improved protection for SSSIs as a result of the CROW (Countryside and Rights of Way) Act, not to mention Mayor Ken Livingstone’s personal commitment to protecting the site, the odds are now against the developer.

What conclusions can be drawn about this astonishing turnaround in the fortunes of Rainham Marshes? That it isn’t over until the bulldozers move in? That beneath the glitter of the multimillion pound corporations lies the common clay of broken promises and unfulfilled dreams? The NCC could try to defend the SSSI on scientific grounds, and Friends of the Earth make waves in environmental waters, but in the end what mattered was the involvement of the local community and a greater sympathy for conservation objectives, which swept on as the case for development crumbled.

Skiing in the Cairngorms

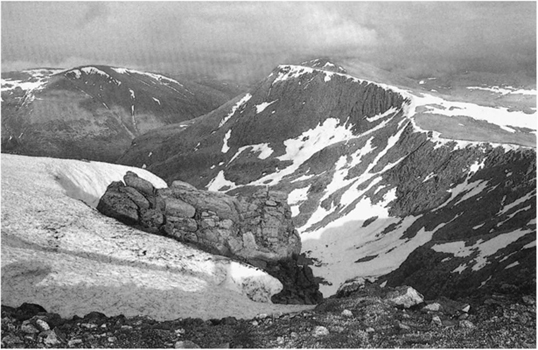

One of the advantages of living in northern Scotland is that so long as there is snow you can go skiing whenever you like. Most places north of Perth now lie within an hour or two of a resort, except in the far north and west where there is seldom enough snow or no suitable slopes. Scottish skiing does have its limitations. There is often a vicious wind, and if you leave the pistes you can soon find yourself marooned in tangled heather or teetering on icy rocks. In some seasons downhill skiers find themselves jam-packed into the limited runs of snow, and you pay as much for the privilege as on alpine pistes of far superior extent and quality. Scottish skiing is mainly a weekend activity. There is only one developed resort with nearby hotels and après-ski facilities and that is Aviemore in Speyside. The ski slopes of Coire Cas on Cairngorm lie just a short car or bus journey away. It was inevitable that downhill skiing and nature conservation interests would find themselves opposed. Areas where snow lies late enough to attract skiers at the peak season in spring, and are also accessible to roads, are limited. Because of their altitude and snow-trapping qualities, such sites often have special vegetation and wildlife. Practically all of Scotland’s downhill skiing areas lie adjacent to, if not within, Sites of Special Scientific Interest. The development at the Lecht and the threatened one at Ben Wyvis lie among some of the best lichen-rich, high level blanket bog in Britain. Glenshee and Aonach Beag lie on mica-schist and limestone rocks noted for their rare flora. Skiing is the one development that penetrates the nesting grounds of mountain birds such as ptarmigan and dotterel, and the inevitable litter attracts predators such as crows (as well as innocent snow buntings, feeding on the crumbs). Constructing runs and facilities on these thin-soiled mountain slopes creates scars that take a long time to heal. The harsh climate and slow growth rate can cause gullying and flash floods, and attempts to revegetate the ground with pasture grasses create anomalous green fairways instead of the natural colours of heather, crowberry and lichen-covered rock. But although Scottish resorts look tacky compared with their sleek alpine counterparts, the direct environmental impact is confined to the skiing area along with their car parks and cafés. The greater problem at Cairngorm is that the chair lifts, which continue to run during the summer, bring visitors within a short distance of the summit, from where you can roam at will over the plateau. In consequence, tracks now radiate from the eroded summit of Cairngorm to nearby corries, the steep defile of Loch Avon and beyond to the distant summit cairn of Ben Macdui, Scotland’s second highest hill. On summer weekends 1,000 or more people walk to the top of Cairngorm and often beyond. The issue goes beyond its obvious effect on wildlife to one of how we treat our finest wilderness – exploitatively, or with reverence and respect.

Skiing and conservation interests managed to coexist without serious conflict until 1981, when the Cairngorm Chairlift Company applied for planning permission to extend its activities westwards into the three northern corries, especially Lurcher’s Gully. It was claimed this would double the size of the resort and greatly increase its profitability as well as easing overcrowding. The application was supported by the Highland Regional Council and the Highlands and Islands Development Board; ranged against it were the NCC and a number of prominent naturalists and hill walkers. The Secretary of State called in the application, and the result was a major public inquiry. For six weeks the eyes of the environmental world were on a village hall in Kingussie. I sat in on a few of its sessions. In the chilly but crowded hall developers and conservationists faced each other across the hall as in Parliament, with the inspector, the press and the public seats completing the square. The unfortunate witnesses were made to sit alone in the middle, where they had to answer as best they could the practised questioning of a QC from across the hall. ‘It comes to this, does it not?’…‘Are you seriously suggesting that…’ ‘Come, come, Mr Morris, two plus two equals four, does it not?’ I remember a lengthy cross-examination over whether the wear and tear around Cairngorm was ‘tolerable’ or ‘not tolerable’. The witness wanted to say it was not, but unfortunately the silk was holding up a letter in which he had said the opposite. ‘It’s just about tolerable,’ he conceded, ‘but fast becoming intolerable’. Back in the hotel, our evening briefings held the excitement of a council of war. A professional conservationist spends much of his life at dreary meetings or behind a desk. Moments of drama are rare, and are cherished accordingly.

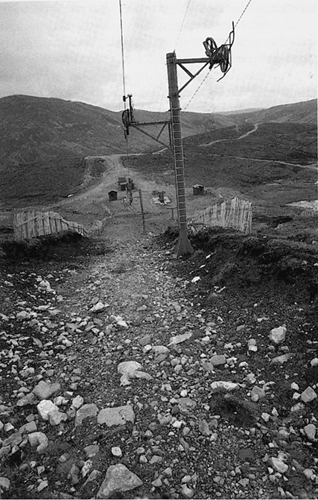

Skiing in Scottish conditions creates eyesores: not only pylons but eroded channels, tatty fences and kiosks, access roads and litter. Would better planning and more investment solve the environmental problems? (English Nature/Peter Wakely)

It helps, of course, to be on the winning side. The NCC did win that inquiry, but it turned out to be only the first round of a protracted battle. In the entrepreneurial atmosphere of the 1980s, no fewer than five separate ski-related developments on SSSIs were approved over the objections of the NCC. One of them broke Scotland’s National Planning Guidelines by extending downhill skiing into a National Nature Reserve, at Caenlochan. Pylons and humming wires now cross that botanically famous ‘amphitheatre with its ring of green alpine flushes’ and rare alpine grasses and sedges, described in the New Naturalist volume, Mountain Flowers. Meanwhile, the chairlift company still had its eyes on Lurcher’s Gully. In 1989, it slapped in another planning application, once again supported by the local council. However, the times were changing, and growing concern about the future of the Cairngorms had found a focus in the Save the Cairngorms campaign, an alliance of 14 voluntary outdoor recreation and conservation bodies. With most of the Scottish media now on their side, and a record 7,000 letters of objection in the minister’s post bag, the application was refused. The Secretary of State went further, announcing in 1990 that the National Planning Guidelines would be revised to rule out any further expansion to the westward of the existing runs on Cairngorm. This was a turning point. No longer could the protagonists of skiing development credibly demonise conservationists as a boffinish élite living outside the area, as they had in 1981. The Scottish Office had affirmed the international importance of the Cairngorms as a wildlife and heritage asset, and had it included in a tentative list of World Heritage Sites. Shortly afterwards the Cairngorms Partnership was established to produce a strategy for the area. In 2001, the prospect of a Cairngorms National Park was real – and near.

Even so, the Highland Regional Council was determined to build up Aviemore into a year-round tourist attraction one way or another. The answer was a funicular railway that could convey a much greater number of people to the upper slopes of Cairngorm than the existing chair lifts. It was the central attraction in a £17 million package fronted by the chairlift company, three-quarters of which would be met by the public purse, including a major contribution from EU funds. Unfortunately Scottish Natural Heritage chose to base its objection on the narrow grounds of consequential pressure on the summit plateau. The developer was able to meet this by amending its plans to exclude access to the summit from the terminus building. SNH felt it had therefore no alternative but to withdraw its objection, thus letting the minister off the hook. This effectively pulled the rug from under the feet of the voluntary bodies. The RSPB had commissioned an alternative, environmentally acceptable scheme based on the more resilient lower slopes in which a gondola would provide a ‘mountain ride experience’ through the pine woods and over the moors, with grand views of the Cairngorm corries beyond. On scenic grounds it would probably have been superior to the funicular railway. Unfortunately, like all carnivores, humans prefer to look down from the heights than to raise aspirant eyes to the summit. The RSPB and WWF asked the courts for a judicial review on the grounds that the proposed development area had been excluded from the proposed SAC at the Cairngorms. They lost, and decided against an appeal because it was felt that this was not the way to woo the new Scottish Parliament. EU funding duly came through in 1999, and construction work on the railway began the following year (it opened just before Christmas 2001). Whether dark warnings about ecological damage and public safety are justified remains to be seen, but those who seek wilderness and solitude in the Cairngorms may have to turn their backs on this place. Perhaps the most important conclusion to be drawn from the long battle over Cairngorm is that people do not necessarily value ‘facilities’ and easy access above wildness. The idea of the Cairngorms as a wilderness, as a place one visits to recharge the batteries and obtain a sense of a world apart from our own, is potent. The railway may give families a fun ride on clear, windless days, but as an idea it is an embarrassment.

Out of sight of the pylons and runs, the heart of the Cairngorms in late May – Garbh Coire with Angel’s Peak and Ben Macdui (left) in the distance.