10 Animals That Get In Our Way

I wonder what kind of nature conservation we would have had if bears, wolves and other large animals still roamed wild in Britain. Perhaps it would have developed more along the American pattern, where National Parks are about wildlife as well as access, or even along the lines of African countries, where big, fierce animals are protected as a major source of foreign income. If so, our nature reserves would have had to be a great deal bigger, and policy would have been centred on vertebrate mammals, not birds or plants. As it is, the few big animals are on the margins and Britain’s conservation policies were based on the management of natural vegetation in relatively small sites. Birds became important because birdwatching is so popular, but in general animals are expected to fend for themselves. We were the last country in Europe to consider reintroducing beavers.

To be a big animal in Britain is to be a nuisance. Most of them have their own Act of Parliament. Seals eat fish, badgers spread disease (it is claimed), deer browse trees and raid crops, and foxes cause class warfare. In short, big animals get in our way. So do some small ones. As guests in this chapter on our uneasy relations with our most attractive mammals and birds, I include the bats, which sometimes take up residence in our homes, and so also get in the way. On the whole, we are kinder to these animals today than we were a generation ago. Perhaps we are even heading towards the other extreme. The public will soon need some persuading that we need to massacre deer to preserve woods, and might even need to be horrid to foxes to preserve peace in the land.

Not a problem after all?

In 1969, Dudley Stamp dedicated several pages of his book to what was then regarded as a problem animal, the grey seal. A large proportion of the world’s population of grey seals breeds around the British Isles. In 1914, when a law established a close season for the first time, there were only a few hundred grey seals in Britain, and not many more in the world. The animal was permanently protected under the Grey Seals Protection Act of 1932, which extended the close season to include the entire breeding season. Since then, their numbers have grown exponentially from hundreds to thousands to tens of thousands, as have complaints that the seals were eating too many fish, especially salmon, as well as damaging fishing nets. In some places, such as the Farne Islands, it seemed that the grey seals might even be harming the environment when their dragging bodies stripped the natural vegetation and caused soil erosion. The 1960s answer was to shoot them, in licensed culls, to keep the population at an agreed level. Since it is difficult to shoot seals in the water, the answer was to kill the seal pups, born in autumn and confined to land during their first few months. Where the animals were numerous, as in Orkney, it was considered prudent to shoot about half the pups born each year.

The calls for grey seal culling came mainly from the fishing industry. The then Nature Conservancy became involved when two of the largest seal rookeries, at the Scottish island of North Rona and the National Trust’s Farne Islands, became National Nature Reserves. As Stamp pointed out, many found it ‘hard to reconcile conservation with the annual carnage of 360 seal pups’ recommended for the Farne Islands by a commission chaired by the Conservancy’s own deputy director. That particular conundrum was solved by the less science-led National Trust, which owned the islands and decided that such scenes of blood and gunsmoke were inappropriate on a nature reserve. However, culls of grey seals went on elsewhere. In 1977 a projected five-year culling programme began in the Outer Hebrides that was intended to reduce the population from about 50,000 to 34,000, the level of a decade earlier. Heavy seas often prevented the Norwegian sealers, commissioned by the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries for Scotland (DAFS), from landing, but they managed to shoot 47 adults and 145 pups at the Monach Isles, another National Nature Reserve. They also managed to dispatch 276 adults and 352 pups at Gasker, an island off Harris. In its annual report, the NCC resported this without comment. These shootings took place out of the public eye, but a similar cull planned for Orkney the following year caused a public outcry. Seals had been traditionally hunted around Orkney until 1962, when stricter controls were introduced. With that partial protection, numbers increased from around 700 to over 1,000 by 1978. During that time the Conservation of Seals Act was passed, which provided a close season for common seals for the first time and gave ministers reserve powers to protect an area throughout the year. Seals that threatened to damage fishing gear – or fish farms – could still be shot, but otherwise killing seals now required a ministry licence. The attempted cull of 800 grey seals at Orkney in 1978 ‘for the prevention of damage to fisheries’ had no real scientific justification. Pictures of the sealers going about their gruesome business were printed on the front page of every family newspaper, and DAFS was forced by the public reaction to abandon the cull. Since then, the grey seal population has grown and grown at roughly 6 per cent per year. Whether they pose much of an economic threat depends on who you talk to, but on fish farms anti-predator nets seem to work so long as they are maintained properly (Berry 2000). Some farms also use ultrasonic scarers.

Since receiving protection in 1970, the common or harbour seal has also increased slowly, especially in The Wash, its main breeding ground (there are smaller numbers at Orkney, Shetland and the Scottish west coast). In 1988, however, disaster struck them in the form of an epidemic of the phocine distemper virus, which killed half the common seals in The Wash, and 10 to 20 per cent of their compatriots elsewhere on the east coast – around 12,000 seals in total. Dogs, failing fish stocks and other unlikely causes were brought in as suspects. At a North Sea conference held in April 1994, Dutch scientists presented convincing evidence that the outbreak was linked to chemical pollutants that had disrupted the seals’ immune systems. Fortunately the epidemic blew over, and grey seals seem to have escaped its effects altogether. Perhaps the common seal undergoes greater risks because of its more frequent use of polluted east coast waters.

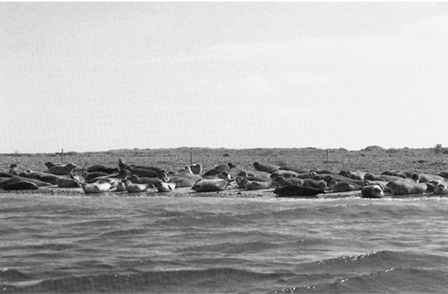

Common seals hauled out on sandbanks at Blakeney Point, Norfolk. (English Nature/Peter Wakely)

Since 1978 there has been no real long-term policy on seals. Local fishermen in Orkney and the Western Isles are licensed to kill seal pups where economic damage can be demonstrated, but large-scale culling has been abandoned. With an environment-friendly image and a healthy tourist business to maintain, local authorities are not calling for its resumption. Indeed, seal-watching trips around the Scottish coast are said to generate £36 million a year in income. It was public opinion that made the difference, not the law, nor any new scientific evidence. The issue came to be seen as a matter of conscience, not merely one of scientific calculation. A six-year study by Aberdeen University ending in 1995 concluded that seals are not responsible for the decline of cod or salmon in Scottish waters. Common seals eat mainly herring and sprat in winter, sand-eels and cephalopods in summer. It was not the seals that have ruined Britain’s fishing industry but the fishermen themselves, and far more effectively and ruthlessly than the poor seals ever could have done.

Persecuting a protected species

The legislation surrounding the badger is a good example of how even a retiring, nocturnal animal that rarely gets in anyone’s way can still attract a lot of attention in a crowded country. Quite a number of different parties are interested in badgers. Conservationists want to conserve them. They do not need to do very much in that direction since badgers are common. They have survived changes in the countryside remarkably well. Very few parts of mainland Britain are badgerless, and the animals even live in suburban gardens. Some desperadoes enjoy cornering and killing badgers with the help of dogs. Although this unpleasant activity has been illegal for decades, an estimated 9,000 animals are killed in this way every year (Morris 1993). Dairy farmers regard badgers with dread, as potential carriers of bovine tuberculosis. The Ministry of Agriculture (MAFF) granted itself the licence to kill a lot of badgers on these grounds. Over 30,000 badgers have been gassed or cage-trapped and shot by MAFF since 1971, with another 12,000 to 20,000 dead badgers targeted for the year 2001 before the foot-and-mouth crisis put operations on hold. Motorists have no particular interest in badgers, but nonetheless manage to run over another 50,000 of them every year. Occasionally a badger makes a nuisance of itself and so has to be caught, tranquillised and moved somewhere else (‘translocated’). For example, in March 2001, a local authority in Scotland spent £30,000 rehousing a family of badgers whose sett had undermined a main road.

Many believe that the Ministry’s campaign against badgers on behalf of cattle farmers is cold-hearted and unnecessary. It started in 1971 when a dead badger was found to be infected with bovine tuberculosis on a farm where some cattle had the same disease. Did the badger catch it from the cattle or vice versa? A quarter of a century and 30,000 dead badgers later, it was still uncertain whether the policy of slaughtering badgers was helping to control the disease. In 1996, Professor John Krebs, then head of NERC, was asked to look into the matter, and advise on the resolution of the problem. The result was the largest-scale biological experiment ever tried out in the field, where all badgers would be trapped and killed in ten different areas measuring 10 square kilometres each. The incidence of TB would then be compared with similar-sized areas where badgers were left unharmed. What was left unclear is what would happen if it was proven that badgers spread disease. Would it then be open season on badgers in cattle-rearing areas? Not according to the Agriculture Minister, who explicitly ruled out a ‘national wholesale eradication of badgers’. In any case, the Krebs trial ran into difficulties. It was difficult, if not impossible, to trap every last badger over 100 square kilometres, and the more badgers that survive, the weaker the data will be. And the longer the trial goes on, the harder it becomes to isolate badgers from other variables. For example, the floods of autumn and winter 2000 confined many cattle to barns where they are less likely to come into contact with badgers. Conservationists such as Malcolm Smith of the Countryside Council for Wales argue that MAFF should be spending more on promoting better farm practices – such as not stuffing cattle so full of chemicals that they have little natural resistance to disease. The NFU indignantly denied that farmers are not taking enough care of their animals, turning a blind eye to the chronic lack of preventative measures against foot rot and diarrhoea in British herds (Lawson 2001). And so we are back to badgers. In 2001, the Commons Agriculture Committee continued to insist that the Krebs trial is ‘the only feasible way of obtaining the information essential to establishing the relationship between bovine TB in cattle and badgers, and whether culling is a viable policy option’. Whether trapping and shooting badgers controls the spread of TB any more effectively than doing nothing will not be known until the full results are available, in 2004 – if then. As this book went to press, there were signs that Government was losing faith in the trial. Computer modelling has cast doubt on the efficacy of culling. The foot-and-mouth crisis put paid to the original timetable. In April 2001, MAFF stated that it was ‘minded to develop a range of policy options’ that could be tried out outside the area of the present trial. This could be the prelude to allowing farmers to cull badgers themselves (Harris 2001).

Despite all the dangers it faces from our own species, the badger is protected as fully as any wild animal can be. Past legislation protected the animal but not its home, thus allowing badger-hunters to escape prosecution by claiming they were digging for foxes, something that was hard to disprove unless they were caught red-handed. In 1992, the Protection of Badgers Act made it an offence not only to harm a badger but to ‘damage, destroy or obstruct’ a badger’s sett. This means it is now illegal to put a dog into a sett. It is also illegal to keep an unlicensed badger as a pet, or even to have a dead one in your house unless you can show it was not killed illegally. In order to close the legal loopholes through which badger-baiters have often escaped, the law comes close to assuming guilt unless it can be proved otherwise. Someone found guilty of hurting a badger can now be heavily fined or thrown into prison for six months. The badger therefore enjoys a degree of protection equivalent to that of an endangered species. The reason is not because badgers are endangered, but because they are popular. As Pat Morris (1993) has remarked, ‘the badger probably has a greater public following than any other British mammal, and its future is thereby as much a political issue as a biological one’. Whether all this protection makes much difference to badgers is doubtful. The threats they face from mankind are as great as ever. Most people today are more familiar with the pathetic, mat-like corpses on busy roads than with the striped face of the live animal as it emerges from its bank and sniffs the evening air.

The ‘branchy beasts’

When Dudley Stamp was writing Nature Conservation in Great Britain there were perhaps 200,000 red deer in Britain, a situation he described as ‘too many deer, chasing too little food on too little land’. He had in mind the emaciated carcasses littering the Highland glens after the severe winter of 1962-63, a sight far removed from the Arcadian beasts roaming Richmond Park. There are even more deer today: some quarter of a million red deer range the Scottish hills, plus an unknown but large number lurking in dense forestry plantations – perhaps 347,000 all told, plus about 12,500 more in England. Yet Fraser Darling reckoned that the most red deer that the land could support without suppressing regeneration and in other ways damaging the environment was about 60,000. In other words, in Scotland we have five or six times the ideal number of red deer. British deer no longer have natural predators. Long ago, the wolf used to do the job, but today deer have to be controlled with the rifle.

In Britain, advice on the conservation and control of red deer is the responsibility of a government commission (formerly the Red Deer Commission, now the Deer Commission for Scotland). There is also a British Deer Society, concerned mainly with welfare issues. The Commission’s task is to promote good deer management by maintaining healthy herds and making sure they do not make an environmental nuisance of themselves. It can, at least in theory, cull deer on private land if their numbers are too high, and pass on the bill to the owner. In practice, however, the Commission’s powers are very limited. Many Highland estates, eager to raise well-antlered trophy stags to attract wealthy stalkers, do not cull as many hinds as they should in the belief that more hinds will produce a greater proportion of trophy stags, which can then be selected by shooting the poorer, less well-endowed ones. More likely, if more hinds were culled, they would free up habitat for the stags, and both stags and their habitat would be the better for it. As it is, in the prevailing grossly overstocked hills poor, runty stags are the norm. Another reason is that hind shooting is often left to the stalkers, who have other claims on their time in winter, or maybe have just grown lazy. The situation has been made worse by artificial feeding in winter, to reduce natural mortality. Conservationists are, of course, less bothered about the size of a deer’s antlers and more worried about overgrazing.

The traditional Scottish ‘deer forest’ was a good habitat for wildlife (or at least it would have been if keepers had been kinder to raptors and carnivores). In the nineteenth century, deer numbers were often low enough to allow some tree regeneration along the valleys and glens, along with thick heather and marshy hollows where the deer would wallow on hot days and find fresh herbage in the spring. With present-day numbers, added to the disastrously heavy stocking of sheep encouraged by CAP headage payments, regeneration has long since come to a virtual standstill except inside tall deer fences – which of course increase the pressure on the remaining unfenced land. Once lush stands of heather, blaeberry and moss are turning into wastelands of short, patchy heather and grass. A side issue is the hideous scars of vehicular tracks created to make stalking easier, while the public were denied access to the hill in case they spoiled the sport.

Red deer are free-ranging wild animals, which nonetheless become the property of an estate owner for as long as they remain alive on his land. However, overall numbers can only be reduced when estates agree and cooperate in a culling programme. If a single owner shot most of his deer, other deer would simply move into the vacuum created, much to the annoyance of his neighbours. This is more or less what happened when NCC staff shot out the deer on its newly acquired holding at Creag Meagaidh during the 1980s. Scientists have had little influence on deer management, despite internationally acclaimed studies of deer on Rum and elsewhere, since estates tend to think they know better. In the 1960s, Morton Boyd and Dick Balharry of the Nature Conservancy got representatives of five estates in Wester Ross to bury their differences and manage the local deer more sustainably as a voluntary co-operative – the Gairloch Conservation Unit. But that did not stop what Boyd described as a ‘tidal wave’ of new forestry plantations making a mockery of any hopes of permanently reducing stocking densities on the open hill. Nor did the Gairloch idea translate well to the Cairngorms, where neighbourhood relations were more frosty.

The situation went from bad to worse until the 1990s, when things suddenly started to improve. A series of mild winters forced some estates to shoot more hinds, since more animals were surviving the winter. The 1996 Deer Act, which created the Deer Commission for Scotland out of the clapped-out Red Deer Commission, also gave it more flexibility and powers to broker ‘voluntary control agreements’ over large areas. But the most significant event of all was the purchase in 1995 of the vast 30,000-hectare Mar Lodge estate in the Cairngorms by the National Trust for Scotland. Experience has shown that practically the only way a conservation body can deal with the red deer problem is to own the land. Hence the NCC succeeded in getting regeneration underway at Inshriach and Creag Meagaidh, which it owned and managed, but not in the rest of the Cairngorms where weak gentlemen’s agreements held sway. The Mar Lodge purchase came with strings attached. The Trust was obliged to maintain sport-stalking – and grouse shooting – by its mysterious benefactor, the ‘Easter Charitable Trust’, thought to be a consortium of Highland landowners who stumped up most of the £5 million purchase price. Even so, Mar Lodge offered an opportunity to manage deer on a sustainable basis over much of the Cairngorms. Deer management is an unsentimental business and the guns have been busy at Mar Lodge, reducing the herd from an estimated 5,000 at the start of the Nineties to within a whisker of its target of 1,650 animals (950 hinds, 750 stags) by 2000. The Mar Lodge experience is being followed closely by deer forest managers all over Scotland. The Trust and its estate staff have entered a long-term management agreement with Scottish Natural Heritage based on the principle of minimum intervention (a little hard to swallow, this phrase, with gun-shots echoing around the glens). A decision was taken not to plant trees or use fertiliser for the time being. If it works, Mar Lodge may influence deer management over much of the Highlands, and bring fresh life to its much-diminished natural woods.

While red deer have been monarchs of many a Highland glen since the mid-nineteenth century, the increase of roe and other deer in lowland woods has been largely a postwar phenomenon. Between the later Middle Ages and the 1950s, roe deer were comparatively scarce animals, confined mainly to Scotland and northern England. Since then they have spread naturally or been released over most of Britain, to be joined by muntjac, sika and fallow deer originating from escapes from deer parks. There are now about half a million roe deer, 100,000 fallow deer, and upwards of 40,000 muntjac and 12,000 sika roaming wild in Britain, and they are all increasing. The presence of much larger densities of deer has profound implications for woodland management, especially for coppicing, the traditional system of regenerating woods based on a cycle of cutting and regrowth. Famous woods such as Hayley Wood and Monks Wood in Cambridgeshire have been ravaged by deer, making a mockery of their management plans. Regeneration is possible only under ‘dead hedges’ of brushwood, or, more certainly, behind ugly, expensive fences. In farmed landscapes, deer tend to use the woods as a secure base, foraying out at dusk to raid the hedgerows and crop fields. They are slowly changing the character of the woods from dense, lush coppice rich in wild flowers to wood-pasture, a more open, less biodiverse landscape based on mature trees and grass.

Oak-hornbeam woodland in Hertfordshire. The dominance of pendulous sedge and brambles may be a response to overgrazing by deer. (Derek Ratcliffe)

What does the conservation-minded woodland manager do about it? He can try to shoot some of the deer, but without co-operative neighbours this is unlikely to be a long-term solution. And small, shy deer in dense woodland make difficult targets. Some members of conservation charities say deer should not be shot, at least not on nature reserves; and there shouldn’t be any fences either. A widely adopted compromise is to fence parts of the wood and try to shoot or evict all the deer inside. But the deer often find a way back, especially when the lush regrowth tempts them in. In the meantime, the impact of deer on woods is an important phenomenon that is receiving enough attention. As the woodland authority George Peterken sardonically notes, ‘If you can’t beat them, learn from them’ (Peterken 1996). By studying the phenomenon, at least you learn something about natural processes. The deer are forcing us to become cleverer woodland managers. The best solution, if there is one, may be an integrated plan that accepts the deer as a fait accompli, but attempts to control their numbers by a mixture of shooting and chemical repellents, combined with rotational fencing. In the meantime anyone contemplating the release of yet more deer from parks should be rather forcibly discouraged.

Strange passions

Anyone who knows the classic New Naturalist monograph, The Herring Gull’s World by Niko Tinbergen, will remember the famous Ravenglass gullery. When Tinbergen was carrying out his studies of bird behaviour on this part of the Cumbrian coast, in the 1950s and 60s, at least 10,000 pairs of black-headed gull nested among the dunes, along with 800 pairs of sandwich terns and other species of gulls, terns and waders. Today, despite Ravenglass’s status as a Local Nature Reserve, all the gulls have gone. The crash began in the 1970s, and after several successive poor seasons they deserted as a body in 1985. The site had not changed much physically, nor had the gull suffered a widespread decline. The reason was predation. And the main predator was the fox.

Foxes had raided the colony for as long as there are records, but the decline and eventual loss of the colony took place during a period between 1966 and 1983 when foxes were no longer controlled. Ironically, this was at the decision of the nature reserve managers, who, after the departure of Tinbergen and his team in 1968, adopted a ‘hands off nature’ approach (Simpson 2001). Nature, they thought, would find its own balance. Unfortunately events showed that without fox control, the ground-nesting birds at Ravenglass did not have a future. What the gulls needed was not laissez faire ‘management’ but a gamekeeper! By the time they started shooting foxes again, in the 1980s, it was too late.

One way or another we do kill a lot of foxes. About 100,000 a year out of an adult population of about a quarter of a million are killed by motorists – knocked down and squashed flat as we rush along crowded roads about our daily business. If the statistics are right, most of us will probably kill at least one fox in the course of our motoring career. Gamekeepers and sheep farmers kill many more, and about 15,000 foxes each year are successfully hunted with hounds. A lot of urban foxes probably die of mange, which wiped out most of Bristol’s well-studied foxes in the mid-1990s. Yet, despite the likelihood that most foxes will meet a violent or unpleasant end before their natural span is out, they are in no need of special protection. Foxes are extraordinarily successful and adaptable animals, occurring in every habitat from remote fellsides to suburban parks and gardens (a favourite hide-out is under the garden shed). They can eat practically anything, from berries, insects and worms to any animal they are capable of catching and killing. Foxes also eat carrion, including leftover chicken dinners in restaurant bin bags. The fox is the commonest large carnivore, not only in Britain but in the world.

Most of the foxes I have seen were dead. I occasionally spot a live one snooping around the house near dusk, mostly in late spring when they raid the waterfowl nests, and sometimes later on when they stalk fledgling pheasants. Usually they see you first, but occasionally you surprise one, intent about its business seeking the daily half-kilogram of meat a fox needs to stay alive. Then it gives a cross, very dog-like bark, slips away through the shadows and halts a safe distance away, no longer a fur-and-tooth animal but a vague dark shape. Normally, however, all you see of the fox is what it leaves behind – droppings, often bejewelled with beetle’s wing-cases, a musky smell around the dustbins, or bits of reddish hair caught in the barbed wire.

To the traditional countryman the fox is, or was, synonymous with the worst kind of vermin, next in popularity to a rat. They are accused of killing lambs (though they take mainly weak or already dead ones, and probably make little difference to the sheep-farm economy). They certainly take pheasants, duck and poultry – the one thing everyone knows about foxes is the orgiastic killing frenzy that often follows when a fox gets into a henhouse or pheasant-rearing pen. Close-up, foxes have unusual eyes with elliptical pupils, which give them a cruel appearance. Such things, and the stories we used to learn at school about wicked Reynard or Brer Fox, helped to create the legend of the cunning, irredeemably wicked fox. More recently, television has created a more benign image, a cuddly, lad-dish creature, like Basil Brush, a small, bushy-tailed doggy, inclined to be a bit naughty, but essentially loveable. Neither image has much to do with real foxes, but anyone who has spent a season trying to protect breeding terns experiences very similar feelings to a poultry farmer after seeing his efforts brought to nothing by a rogue fox.

Conservation bodies have been uncharacteristically quiet during the great debate about the rights and wrongs of fox hunting. While hunting has little effect on overall fox numbers, since more animals are killed by trapping and shooting than by dogs, the issue has become an emotional tripwire. The reason for the silence from the nature conservation end is that membership bodies dare not say anything for fear they will lose members. The country agencies say nothing because the matter is politically sensitive. In its comments to the Burns Inquiry, English Nature insisted that hunting was not a conservation issue since foxes were natural predators and nature has its own way of finding a balance. Essentially this is because foxes live in social groups that establish and defend a territory. Because of this behaviour, foxes have their own method of population control. In towns, however, the density of foxes is greater purely because of artificial feeding. In Bristol, about ten per cent of householders regularly left out food for ‘their’ foxes (Baker et al., 2001). What English Nature did not mention is that a ban on hunting, whatever its effect on foxes, whatever its possible ethical merits, would undoubtedly strain relations between conservation agencies and country landowners.

Before it was cancelled because of foot-and-mouth, an expected half-million people were expected to join a countryside march in London on 17 March 2001. A ban on hunting clearly concerns many who do not actually hunt themselves. Some believe it would be the thin end of the wedge, the start of a general assault on country sports, including angling, led by animal-rights groups claiming massive, if largely passive, public support. More broadly, the hunting issue symbolises a clash of sensibilities: of a culture based on modernisation and change pitted against one of custom and tradition. There is a great fear nowadays of being seen to be incorrect, a sense that old-fashioned liberality is being replaced in many quarters with an enforced conformity based on moral absolutes. It seems to make little difference that the Burns Inquiry was unable to make up its mind whether hunting was cruel (or, indeed, about anything else), when so many people are obviously convinced that it is. The two views are irreconcilable. A sensible government will try to calm things down.

The fox is potentially the joker in the nature conservation pack. He is only a common natural predator going about his business, but because he enters gardens, and eats the food put out for him, the fox has become for many a kind of outdoor pet. He has transcended wildness and become property. But if country, as well as town, foxes are to be given the status of a pet, then other forms of wildlife will suffer for our sentimental indulgence.

Wild geese

Wild geese are one of conservation’s success stories. True, goose populations were relatively low in the postwar years when the first national counts were made, but the numbers of most species of geese overwintering in Britain multiplied by a factor of three or four over the next 30 years. The 30,000 pink-footed geese present in 1950-51 had increased to 101,000 by 1983. The bigger greylag goose underwent a similar increase from 26,500 in 1960 to just over 100,000 in 1984 (Lack 1986). On Islay alone, the rarer barnacle goose increased eightfold from around 3,000 in the 1950s to 24,000 in 1978, a quantity that local farmers, whose valuable grass they ate, considered to be much more than enough. With the exception of some of the greylags, and the introduced Canada goose, all these birds breed in the arctic tundra. Britain, and especially Scotland, becomes an important base for them in late autumn, a landing stage for geese from Greenland, Iceland and Spitzbergen. Geese that traditionally eat barley grain, such as the pinkfoot and the greylag, congregate in east and central Scotland. Grass-feeding geese, such as the barnacles and white-fronts, prefer the west coast, with its mild winters and early ‘bite’ of new shoots. For these months, Britain and Ireland become a place of world importance for wild geese: we are host to around three-quarters of the world’s pink-footed geese, half the dark-bellied race of the brent goose, a third of the barnacle geese, and the whole of the distinctive Greenland race of the white-fronted goose. When I lived in Aberdeenshire, one of the great wildlife spectacles was the grey skeins of pink-footed geese coming in to roost on the loch as the autumn sky turned rosy-pink. The call of wild geese still ignites in me blood memories of cold, exhilarating mornings, waiting in the darkness amid the reeds for the moment when fresh, feathered food from Iceland passes over the gun barrels. Their great northern journeys excite wonder, as does their cleverness in capitalising on the way we are changing the land.

Brent geese on the Blackwater estuary in Essex. (English Nature/Peter Wakely)

Why are wild geese doing so well? It seems to be through a combination of protection and food supply. The more geese that survive the winter in Britain, the more will return to breed in the limitless, mosquito-infested polar wilds. Wild geese in Britain had a hard war, followed by a period of fairly intensive wildfowling in the late 1940s. However, the conservation pioneers led by the Wildfowl Trust went to a great deal of trouble to establish sanctuaries where wild geese and other wildfowl could roost and feed undisturbed. The first formal Wildfowl Refuge was set up on the Humber in 1955, followed by others on the Ribble at Southport, Caerlaverock in Dumfries, Lindisfarne in Northumberland, Tentsmuir Point in Fife and elsewhere. Some of these places later became nature reserves, where the shooting was regulated by the Nature Conservancy. In the new climate of the 1950s, with the Protection of Birds Act, and the growing popularity of birdwatching, wildfowlers, give or take a few independent ‘cowboys’, broadly supported the scheme.

At that time, wild geese fed mainly on salt marshes on and around estuaries, or, in the case of the pink-footed and greylag geese, on waste grain in barley stubble, followed by raids into fields of turnips and potatoes. However, by the 1970s, their behaviour was changing. The sowing of cereals in autumn instead of spring might have robbed the geese of their stubble fields, but it substituted an almost limitless supply of fresh cereal shoots. Similarly, the fertilisation of pastures or their replacement with fresh-sown leys produced supplies of tender grass, especially along the landfalls of the geese on the Scottish west coast. The geese also approved of the big new fields created to accommodate combine harvesters, since it gave these nervous birds a much better view. They tend to stay in the same place longer than in the past. New reservoirs were requisitioned by greylag and pink-footed geese as roosting spaces, and gave them the opportunity to move further inland. Even the relatively conservative brent goose had discovered the potential of autumn-sown cereals and oilseed rape by the mid-1970s, and began to feed inland. Of course, these new opportunities brought wild geese into conflict with farmers. On the wealthy grain farms of eastern Britain, the loss of up to 5 per cent of the crop to geese might not have dented the farm income too seriously, but in marginal areas, such as the Western and Northern Isles, agricultural damage was more serious. In particular, the habit of the barnacle goose of feeding as a single vast flock, like a swarm of feathered locusts, made them very unpopular on Islay. In global terms, the barnacle goose is rare. It just happens that most of them visit Islay.

The problem came to a crux in 1981, when, in line with our international commitments, Britain extended full protection to the brent and barnacle goose – and, in Scotland, to the white-fronted goose – at a time when goose numbers were at an all-time high. The NCC wanted to designate certain key areas as SSSIs, and try to work out agreements with farmers by creating undisturbed refuges in the hope that the geese would congregate there. In the meantime farmers would be compensated for agricultural damage. But many farmers preferred the traditional method of inviting in the marksmen. This now required a licence, which the Scottish agriculture department seemed more than willing to issue ‘to prevent serious agricultural damage’. It soon became clear that the system was being abused, and that some of the geese were being shot for sport, as in the good old days. On Islay, the flock of barnacle geese fell from a peak 24,000 in 1976 to 15,000 in 1983. ‘Shooting was undoubtedly a contributory factor,’ wrote the NCC in its annual report to the minister. The Secretary of State for Scotland took the line that until management agreements had been sorted out, he would continue to dispense licences. One of the sticking points, as far as some of the islanders were concerned, was that they didn’t believe the conservationists’ figures. There were far more geese than was claimed. There was also considerable doubt about the efficacy of alternative ways of scaring geese away, for example, by flying kites. The trouble is that wild geese are not stupid. They are capable of learning that kites are not hovering birds of prey, and even to judge when the close season arrives (with warmer weather), when the shotgun blasts go over their heads and are not aiming at them.

Since the 1980s, it has been government policy to compensate farmers on Islay whose land has been damaged by geese. By 1994, this worked out at £9.50 per goose per year, totalling around £300,000. Noticing this, farmers in other parts of Scotland visited by large numbers of wild geese demanded similar compensation. Scottish Natural Heritage, which had to foot the bill, questioned the legitimacy of such payments, pointing out that it was paying for damage to crops and pastures whose productivity was made possible only by subsidies for agricultural production. In other words, the taxpayer was in effect paying for the crops and paying for the geese. SNH favoured an alternative scheme, pioneered at the Loch of Strathbeg in Aberdeenshire, where farmers are paid to take land out of production altogether as ‘sacrificial fields’ for the geese. These fields are fertilised or reseeded to bring on sweet, early bites of grass for the geese, which has the added advantage of concentrating the flocks in a particular place and so improving the birdwatching. Stubborn birds can be persuaded to use them with the help of bird-scarers. This system is now in place in many parts of Scotland, with payments available from agri-environment schemes, such as Environmentally Sensitive Areas.

In 1997, the Government established a National Goose Forum, administered by SNH, to advise ministers on goose management (the new word for goose control) in Scotland. SNH continues to run compensation schemes on Islay, the Solway Firth and on South Walls in Orkney. In the latter, refuge areas have been created along the lines of the Loch of Strathbeg model. On Islay, on the other hand, SNH pays around £400,000 a year on 118 individual agreements to protect some 32,000 barnacle geese and 12,700 Greenland white-fronted geese ‘from disturbance and shooting’. The lessons learned, it says, have ‘contributed significantly’ to the development of a National Policy Framework on how to live side by side with wild geese. The answer is that we do so by paying for them.

An endangered species in the loft: bats and their conservation

When I was in the NCC, in the early 1980s, I climbed into quite a number of loft spaces to look for bats, and well remember the atavistic thrill of entering their dark world, feeling the breath of their faintly flittering wings against my face. Since then I have shared a house with a large colony of pipistrelles, which tended to make their presence known in the heat of summer, when, despite claims to the contrary in the conservation literature, the smell of accumulated droppings and urine made parts of the house uninhabitable. (We told everybody that these droppings are just the thing for roses – rather rash advice, I fear.)

Unlike birds, bats, with the exception of the endangered greater horseshoe bat, received no legal protection until 1981. Then the Government made up for its previous neglect and protected the lot of them, common and rare alike. It was full protection, too, extending to their roosts and winter sites (hibernacula), and forbade people to so much as touch them without a licence (though you were allowed to evict them gently from any room you happened to be living in). The Wildlife and Countryside Act protected British bats more comprehensively than any other native mammal, and, at the time, than any other country (Morris 1993). What made it all the more remarkable was that bats frequently choose to live in our homes; nearly half of all bat colonies are in ordinary houses built since 1960. As far as a bat is concerned, a house roof is an attractive combination of cave and giant hollow tree. Thus protection brought every Englishman’s castle within the law as bat habitats.

There was considerable justification for all the fuss. Probably the still common pipistrelle was included because it was regonised that most people cannot tell one kind of bat from another. But all British bats were declining in numbers. The greater horseshoe bat, which is relatively easy to survey because of its habit of congregating in a limited number of hibernating places, had spiralled down from an estimated 300,000 individuals in 1950 to only 4,000 in 1993. The fundamental reason is that bats are finding it harder to find enough insect food. There are fewer hedges and copses, and suitable stretches of water. Even cow dung, once an important source of flies, is nowadays virtually sterile thanks to the drug Ivermectin, used to get rid of internal bovine parasites. The two horseshoe bats experience a particularly hard time, since they feed on cockchafers and other large insects dependent on permanent pasture. They are in danger of using up more energy finding food than they gain from eating it. Forest hygiene methods that insisted on removing all dead wood were also removing the homes of bats, such as the noctule, which use hollow spaces in trees. Another danger to bats was the use by timber treatment firms of highly toxic, lindane-based sprays to prevent dry rot or woodworm. These are fatal to any bats unlucky enough to come into contact with them.

For all these reasons, bats have become one of the great conservation crusades of the late twentieth century. Legal protection for bats does not achieve a great deal by itself. To bring a case against a householder or timber treatment company is difficult, and the magistrates usually let them off with a token fine. But the handful of cases that came to court helped to publicise the problem, and persuade the companies to contact the NCC or a ‘bat worker’ first. Soon the NCC was receiving about 2,000 inquiries a year, most of which were passed on to a growing band of licensed bat experts. The result would be a call, and an opportunity to put the case for bats. A survey conducted during a ‘National Bat Week’ in 1990 suggested that while three-quarters of home owners did not like bats very much, most of them were won round after being ‘given some facts about bats’. The NCC gave away 60,000 copies of its leaflet, Focus on Bats (featuring a particularly cute long-eared bat). If a home owner insisted on eviction, a way could normally be found without harming the creatures, for example by identifying and blocking the exit holes once they had dispersed. Among the more awkward cases were churches, where bats made themselves unpopular by soiling the altar cloth with their droppings. At least one vicar tried to scare them away by revving his motorcycle up and down the aisle. But the majority of people agreed to share their homes with the bats, which, I think, does them credit.

The image of bats has mellowed considerably since 1981, thanks partly to sympathetic television programmes but, above all, to the dedication and domiciliary visits of members of the local bat groups. The Bat Conservation Trust was founded in 1991, and now has over 2,000 active members – more than the Mammal Society – and 90 local groups, one for nearly every county in England and Wales. Our knowledge of where and how bats live has vastly improved as a result, helped by the invention of hi-tech ‘bat detectors’, which identify bats by their distinctive high-frequency calls. Bat detectors helped to discover two new species of British bat in the 1990s: Nathusius’ pipistrelle, which is probably a migrant and recent colonist, and another, now called the soprano pipistrelle, distinguished by its high-pitched call. The latter species is now known to be widespread, turning up in many bat boxes, especially woodland. University research is also refining knowledge of bat behaviour, for example, by showing that the Daubenton’s or water bat prefers placid, sheltered, open waters, and finds it difficult to detect food among dense waterweed or ripples.

Since bats are sociable animals, and highly faithful to a particular roost or hibernation site, it has been possible to protect some of their homes. Many cave entrances have been covered with grilles to protect them from disturbance, with the co-operation of caving societies. (On the other hand, safety legislation compelled some local authorities to seal the entrances of disused mineshafts, incarcerating several colonies of horseshoe bats in the process, until they were persuaded to substitute a grille.) Specially designed bat boxes have proved effective for some species, such as pipistrelles and long-eared bats. Important sites such as Greywell Tunnel on the Basingstoke Canal have been made Sites of Special Scientific Interest and the subject of management agreements. Perhaps the most interesting example is the derelict Gothic mansion in Woodchester Park, Gloucestershire, never lived in by humans, but now home to greater horseshoe bats, which roost in the chimneys. Another horseshoe bat roost, in some crumbling farm buildings in Devon, has also been acquired and restored, with the help of the Vincent Wildlife Trust. One even hears talk of electrically heated roosts; perhaps the elusive Bechstein’s bat would appreciate these, for only the second colony ever found in Britain was in an unexpected place – an airing cupboard!

British bats and their estimated numbers (from Harris et al. 1995)

| Species | Adult population |

|---|---|

| Greater Horseshoe | 4,000 |

| Lesser Horseshoe | 14,000 |

| Whiskered/Brandt’s | 70,000 |

| Daubenton’s | 150,000 |

| Natterer’s | 100,000 |

| Bechstein’s | 1,500 |

| Barbastelle | 5,000 |

| Pipistrelle | 2,000,000 |

| Soprano Pipistrelle | Unknown, but lots |

| Serotine | 15,000+ |

| Noctule | 50,000 |

| Leisler’s | 10,000 |

| Brown Long-Eared | 200,000 |

| Grey Long-Eared | 1,000 |

Raptors: the problems of success

The recovery of Britain’s birds of prey since the banning of organochlorine pesticides in the 1970s, as well as the reduction in persecution, has been another of the brighter corners of the nature conservation world. Our population of peregrines has more than recovered its pre-war level, and this regal falcon now nests on cliffs on the southern coast from Cornwall to Kent, and increasingly in quarries inland. Around 30 pairs nest on tall buildings or pylons, sometimes in towns; a pair was reported even using the Millennium Dome. The marsh harrier, once reduced by pesticides and persecution to just half a dozen pairs, now follows the ploughs in Essex fields and is a frequent sight over East Anglian marshes. The buzzard returned in triumph to much of England during the 1990s. (A noisy pair nests in a poplar tree just a few score yards from my Wiltshire house.) The sparrowhawk, which has fully recovered its former range and often hunts in suburban gardens, is now common enough to be controversial: it has been blamed, probably wrongly, for decimating garden birds (your cat will take more, but the real cause is the absence of seeds and grain in modern farm fields). Thanks to reintroductions and escapes we now have red kites and goshawks in numbers unknown for centuries.

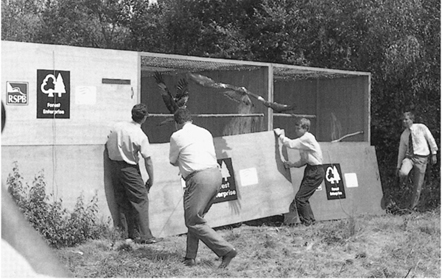

Release of captive-bred red kites at a woodland site in England in 1997. (English Nature/Peter Wakely)

For some species, recovery has been rapid, for others slow or non-existent. Since 1990, however, the overall recovery rate has slowed down, and peregrine, hen harrier and sparrowhawk numbers have fallen slightly. For the first two the cause must be persecution. In its 1991 report, Death by Design, the RSPB produced evidence of widespread use of poisoned bait and pole-traps in pheasant-rearing areas and on upland moors. The documented cases, which accounted for 40 golden eagles, 65 peregrines, 57 hen harriers, 39 goshawks, 24 red kites and 367 buzzards, probably represent just the tip of the iceberg. Between 1995 and 1999, a further 100 incidents were documented in Scotland alone, of which 39 involved poison (Scottish Executive 2001). On the moors of northern England the situation is said to be even worse; successfully breeding hen harriers in England fell to just five pairs in 2000, yet on English Nature’s estimate there is enough habitat for 240 pairs. Egg theft is also rife, for this form of trophy hunting still attracts its share of fanatics. Scottish Executive’s report, The Nature of Scotland, cites a particular eagle’s nest in Perthshire that had been guarded around the clock, only for the successful fledgling to succumb to poisoned bait shortly afterwards. The incidents of poisoning show no sign of declining, and, in the case of golden eagles and hen harriers, were higher in 2000 than in previous years.

Ian Prestt, late director of the RSPB, by a crow trap on a Borders grouse moor. (Derek Ratcliffe)

The reason why raptors are unpopular in some quarters is, of course, because they take birds that have a value and are regarded as property, specifically grouse and racing pigeons. Whether raptors are to blame for the falling numbers of red grouse has long been hotly debated. In 1992, a grouse moor at Langholm in Dumfriesshire, once celebrated for its game bags (2,523 grouse were shot there in a single day in 1911 – a Scottish record), was chosen by the Joint Raptor Study Group, representing ornithologists and moorland managers, for an experiment. Over five years, the effect of raptors on grouse numbers was carefully monitored. The resulting report seemed to confirm what the keepers had been saying all along. The raptors increased, but the grouse did not. Hen harriers killed 30 per cent of breeding grouse every spring, 37 per cent of the chicks each summer and 30 per cent of the surviving chicks the following autumn. The seasonal bag of grouse declined from 4,000 to 100, at which level the management costs of the moor could apparently no longer be met. In 1998, grouse shooting at Langholm was mothballed. However, it is more complicated than that. The estate had reduced sheep numbers, allowing the grass to grow rank and harbour higher vole densities than usual, and more voles meant more harriers. At the same time, half of the heather present in the 1940s had disappeared, producing a long-term decline in grouse. On other, more heather-dominated moors the predation of grouse was much less. Langholm, in other words, seems to have been an exceptional case. As for what should be done about it, some parties to the report advocated the licensed removal of harrier chicks from grouse moors, releasing them on other, grassier moors where they would feed harmlessly on pipits and voles. Another possibility discussed was an agreed ‘quota’ of harriers, enforced by pricking surplus eggs. The RSPB opposed such schemes, preferring an alternative in which ‘diversionary food’ would be offered to the harriers, just as dovecotes have been set up on some grouse moors to divert the peregrines. The issue is a sensitive one. The Scottish Gamekeepers Association is adamant that in some areas hen harriers must be ‘culled’ to allow ‘a sustainable harvest of grouse’. But of course the hen harrier is a protected species, and although the Scottish Executive could license such a cull, it would be sure to be strenuously opposed. Some moorland managers nonetheless destroy harrier nests outside the breeding season, which is arguably legal, and burn out the tall, leggy heather that harriers prefer. A few, as we know, resort to illegal poisons or shooting, presumably with the tacit approval, if not the connivance, of the laird.

A second cause of controversy is racing pigeons. In some districts peregrines are blamed for taking an unacceptable number of these birds, especially inexperienced youngsters; sparrowhawks are also accused of killing homing pigeons. Mysteriously, peregrines are declining in parts of the country. A recent report to the DETR suggests that the peregrines are mainly picking off stray birds. The UK Raptor Working Group has suggested re-routing and delaying the races to reduce predation, which reportedly works quite well.

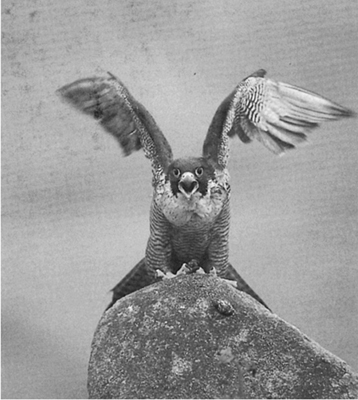

A peregrine falcon celebrates its recovery from pesticides and persecution. (HarperCollins Publishers)

Why make such a fuss about raptors when, compared with many species, they are not faring too badly? The Scottish Executive’s forthright answer is that persecution is illegal, and that all wildlife deserves to be treated with respect ‘as part of what makes our country special’. Just as racing pigeons are the property of their owner, so, at least in a legal sense, wild birds are the property of the nation. However, while willing to enforce the law, and, if necessary, increase the penalties in the few cases of persecution that stand up to legal proof, Scotland’s institutions prefer to work out a solution by consensus. At the time of writing, the Scottish Executive is considering the recommendations of a report produced by the UK Raptor Working Group in 2000, which calls for stronger powers to convict offenders combined with greater support for moorland managers – and (of course) more monitoring and research. Although this fragile alliance of managers, bird experts and administrators is beset by tensions, it is hoped that the kernel of common ground – the desire for large areas of healthy, regenerating heather – may provide a way forward.