11 Biodiversity

Biodiversity became one of the buzzwords of the 1990s, just as Ecology was in the 1970s. The word ecology was coined by the German biologist, Ernest Haeckel, from the Greek oikos or home – for ecology was about the study of an animal or plant’s ‘home’ or habitat. ‘Biodiversity’ was invented, or at least popularised, by the American ecologist, E.O. Wilson. It is a characteristic modern compound-noun, combining ‘biological’ and ‘diversity’, and means what it says: living things in all their infinite variety, including genetic variation within species. When traditional English was still spoken we would have referred to it as ‘the variety of life’. Biodiversity is not just about species, but about the communities and habitats they form together. In his well-known book, The Diversity of Life, Wilson demonstrated that the variety of life on earth is greater than anyone imagined, but it is also threatened as never before by the rate of consumption of the world’s natural resources. According to him, the probable extinction rate is a hundred, perhaps even a thousand times as high today as it would have been had people not existed (one has to say ‘probable’ because we have still discovered and described only a fraction of life on earth). Not only will this make the world a duller place, but it risks damaging our own interests. Some forms of life, perhaps unknown to us, will be ‘keystone species’, says Wilson, whose loss would drag down an entire ecosystem. For example, a large number of species depend on the nests of the wood ant. If something happened to the ant, we would also say goodbye to a whole swarm of moths, beetles and hoverflies. Equally, a single ill-judged action can quickly kill off a whole tribe of wildlife. On the Hawaiian island of Oahu hundreds of endemic snails were driven beyond the brink into extinction by an imported mollusc: introduced to control an African pest, it ate the native snails instead. Yet the place still looks like a tropical island paradise. It has lost its special species invisibly. Most extinct species are very small because nearly all life is very small. But being small does not make you insignificant. The most significant predator in the British countryside is not the fox or the eagle, but the ant. The environmental health of soil or fresh water might depend on some protozoan or micro-fungus that only a handful of experts could even recognise.

As the godfather of ‘state of the planet’ studies, Wilson’s books command a respectful international readership. Hence it was with fresh memories of The Diversity of Life that participants at the ‘Earth Summit’ conference in 1992 started to use the term ‘biodiversity’ instead of ‘species diversity’. The UN conference on Environment and Development was held at Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, in a specially designed conference centre, casually – and ironically – built on an erstwhile wetland, rich in departed species. The leaders of 178 nations came together with varying degrees of reluctance to talk environment. It was apparently the largest-ever summit gathering, and seemed to signal that the whole world had suddenly cottoned on to the fact that damaging the environment harms our own future. What made this conference different from less well-attended predecessors was that it bound signatory nations to the principles of sustainable development and biodiversity. Each country agreed to draft its own ‘Agenda 21’ – a blueprint for sustainable growth intended to try and make the twenty-first century more environment friendly than the twentieth. Among the documents signed was the Convention for Biological Diversity.

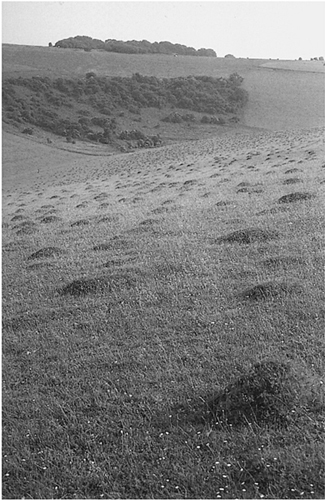

A keystone species? Hills of the yellow ant dotting ancient downland turf at Wylye Downs NNR are themselves a mini-habitat for many species of plants and insects.

To everyone’s surprise, the UK Government seemed to take all this seriously. Civil servants in the then Department of Environment took up their pens and, by the start of 1994 (which by Whitehall standards is almost reckless haste), had produced a quartet of White Papers. The first three, on sustainable development and climate change, need not detain us. The fourth was the beginnings of the UK Biodiversity Action Plan. At this stage it was more of a review than a plan, concerned mainly with itemising current policies and procedures in education, science and nature conservation that related to biodiversity. But it did set Government a goal: ‘to conserve and enhance biological diversity within the UK and to contribute to the conservation of global biodiversity through all appropriate mechanisms’. Specifically, it would produce action plans for a wide range of species and habitats that had either declined or in some way incarnated environmental quality. In the usual way, Government set up a steering group, composed of officials from government departments and agencies, and also representatives from scientific institutions and voluntary bodies. Meanwhile a consortium of the voluntary bodies (RSPB, the Wildlife Trusts, WWF-UK, Friends of the Earth, Plantlife, Butterfly Conservation), gingered up at Rio by a mini-conference of their own, threw down the gauntlet by publishing their own ideas just ahead of the Government’s. The document was called Biodiversity Challenge.

Biodiversity Challenge is one of the milestones on the journey of the voluntary bodies from amateur natural history societies to partners in environmental policy-making. The challenge was to halt the decline of biodiversity in Britain by rescuing threatened species and habitats, and place Britain at the forefront of world conservation policy. The report drew up a formidable list of species and habitats, and set out in some detail what needed to be done, who should do it, and how we should know when we had done it. In the first place, argued Sir William Wilkinson in his foreword, ‘we must have clear objectives’. The goals should be ambitious but attainable. Each mini-plan on a species or a habitat was to be confined to a ten-year period, and nailed down with costings and a ‘realistic’ target. Wilkinson and his team were keen to demonstrate that the voluntary bodies could be as hard-headed as any businessman when it came to investment analysis and the delivery of defined goals. They were also anxious to force the pace before the self-congratulatory glow of Rio had dimmed and people had found something else to talk about. In Britain, ‘lack of information is not the major problem’, claimed the voluntary bodies. They could tell us which species are threatened and in many cases state in fairly exact terms what action is needed to save them. But conservation bodies could not do this work alone: putting biodiversity planning into practice had to be a partnership, using the far greater resources of national, regional and local government, as well as private business. Biodiversity Challenge reminded Government that species are a good way of measuring the sustainability of your policies. If they make species die out, your policies are not sustainable. Since they are interdependent, to sustain the environment you have to sustain species. Without a Biodiversity Action Plan up and running, they concluded, the other Rio documents on sustainable development would be worthless. Cheekily, the voluntary bodies added that if Government considered their ‘rather modest targets’ overambitious, it should do the sums itself, and then submit them to ‘public debate’.

The constant refrain of Biodiversity Challenge was ‘ambitious but realistic’. It proposed a vast programme of work that would not only require research but oblige bodies to work together to a common programme, instead of in the traditional watertight compartments and client groups. Behind the swarms of rare species and archipelagos of beleaguered habitats, it set out a series of broad principles, a kind of environmental Ten Commandments. All uses of ‘biological resources’ should henceforth be sustainable. Non-renewable resources must be shepherded and used wisely and cautiously. Damage to the environment was only justifiable where ‘the benefits outweigh the environmental costs’. Important projects should be appraised environmentally as well as financially. Subsidies leading to the loss of biodiversity (for example, in much of current forestry and agriculture practice) should be withdrawn. ‘Critical natural capital’ must be conserved. Biodiversity Challenge’s optimistic supposition was that a crowded island of 58 million human inhabitants – 3.6 persons per hectare in England – can sustain most of its material aspirations without damaging the environment. A challenge indeed. But as the very first paragraph points out, at least two million out of those 58 million were members of one or more of the bodies that produced Biodiversity Challenge.

We are still discovering new species. This is an overlooked native tree, service or whitty pear, Sorbus domestica, with its proud finders, Mark and Clare Kitchen.

The Government’s response, the Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP), is Britain’s blueprint for conserving the full variety of natural communities and habitats together with all their constituent species. It identifies a series of objectives for conserving biodiversity and commits the Government to take ‘59 steps’ in that direction. The Plan is essentially a digest of consensual conservation philosophy as it stood in 1994. Its underlying principles include ideas of sustainable use, of due precaution when making decisions, and the need for sound knowledge to guide policy and action. It implicitly demands policy changes in every activity dependent on natural resources – farming, fishing, energy, forestry. The Plan also aims to involve more people in conservation activities, and to contribute British know-how to Europe and elsewhere in the world. Above all it recognises that conserving biodiversity should be ‘an integral part of Government programmes, policy and action’ (this aspiration received its ‘statutory underpinning’ in law six years later, in 2000).

The BAP is stuffed with fine, hopeful words such as ‘healthy’, ‘enhance’ and ‘encourage’, but nevertheless is rather short on specific ideas. Many of the ‘59 steps’ take the form of general exhortations (‘encourage the regeneration of woodland’) or restatements of present activity (‘continue English Nature’s species recovery programme’). The official BAP Steering Group leaned heavily on Biodiversity Challenge for information, and the bulk of its recommendations are concerned with just one of the 59 steps, though arguably the biggest one: prepare plans for threatened species and their habitats. After all, if we continued to lose wildlife despite all the fine words, then the rest of the plan would be worthless. This is what is truly radical about the BAP: it has fastened a grand edifice of sustainable land-use policy to the backs of a collection of wild plants and animals that we are hardly even aware of, as though our future depends on our ability to sustain and enhance flamingo moss, narrow-headed ant and thistle broom-rape. Needless to say, those of us that know and cherish these obscure things were overjoyed.

The Steering Group, charged with taking the plan forward, published its first ‘tranche’ of action plans commendably quickly, in 1995. Most of its 116 Species Action Plans (SAPs) and 14 Habitat Action Plans (HAPs) were cherry-picked from Biodiversity Challenge and then worked up by the JNCC. To qualify, a species had to be rare (‘found in fewer than 15 ten-kilometre grid squares’), or fast declining (‘by more than 25 per cent in the past 25 years’) or for Britain to contain a quarter or more of the world population. Legally protected species would also qualify. The action plans are written to a formula. They are brief – a couple of pages and a map – and so necessarily generalised. They outline the ‘current status’ of a species, suggest why it is rare or declining, what has been done to conserve it and what needs doing. The rest of the plan farms out the proposed work to different ‘lead agencies’ and assigns a target for the first ten years. For example, the plan for the nightjar is to increase the number of ‘churring males’ from about 3,400 to 4,000, and begin to re-establish the bird in parts of its former range. To achieve even this limited objective would require the restoration of heathland, enough clearings in large forests and, more vaguely, ‘promoting extensive agriculture systems in the wider countryside’. Everybody is given a job: Forest Enterprise must bear in mind the nightjar ‘when considering felling and restocking proposals’, the agriculture departments must ‘support extensive low-intensity agricultural systems’, English Nature must broaden its wildlife grants to cover ‘key areas of lowland heathland’, and the JNCC is made responsible for monitoring nightjar numbers. While much of the plan is kept nice and vague, a zealous interpretation would imply quite far-reaching changes. And all this just for the nightjar. Fortunately, efforts made on behalf of the nightjar should also benefit the woodlark and other BAP species.

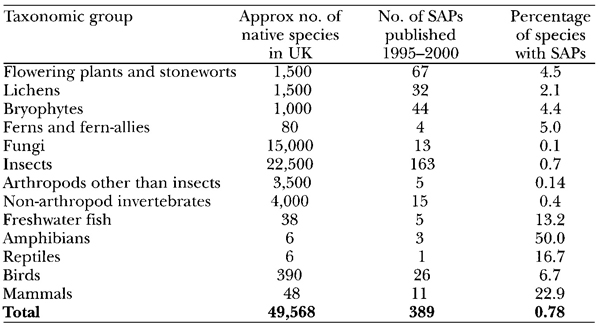

Species bias: the proportion of species with action plans (Source – Biodiversity: The UK Action Plan/JNCC Annual Report ‘96/’97). We have not yet made any plans for conserving species of protozoa, bacteria or viruses.

UK Biodiversity Action Plan: terrestrial Habitat Action Plans

Ancient and/or species-rich hedgerows

Aquifer-fed, naturally fluctuating water bodies

Blanket bog

Cereal field margins

Chalk rivers

Coastal and flood-plain grazing marsh

Coastal salt marsh

Coastal sand dunes

Coastal, vegetated shingle

Eutrophic standing waters

Fens

Limestone pavements

Lowland beech and yew woodland

Lowland calcareous grassland

Lowland dry acid grassland

Lowland heathland

Lowland meadows

Lowland raised bog

Lowland wood pasture and parkland

Machair

Maritime cliff and slopes

Mesotrophic standing water

Mudflats

Native pine woodlands

Purple moor-grass and rush pastures

Reed beds

Upland calcareous grassland

Upland hay meadows

Upland heathland

Upland mixed ash woods

Upland oak wood

Wet woodland

Of course, the Biodiversity Action Plan was not the first time rare species had attracted attention. The NCC had funded research on endangered species from otters and red squirrels to snow gentians and lady’s slipper orchids. The gauntlet was taken up by its successor bodies, who, to provide some extra originality, lumped the projects together in special programmes. By the 1990s the voluntary bodies had started joining in as ‘lead partners’. Bats, butterflies and wild flowers now had parent conservation societies in the form of the Bat Conservation Trust, Butterfly Conservation and Plantlife, who were eager to take part, not least because Biodiversity projects gave them an expanded raison d’être. Similarly mammals, birds and ‘herptiles’ had respective active societies in the Mammal Society, RSPB and British Herpetological Society. For the less well-known orders, such as bees, lichens and snails, lead partners were harder to find. Fortunately the study of rare species in the field holds enormous appeal for many naturalists, both amateur and professional. For example, the ecologist Terry Wells took on the saving of the ribbon-leaved water-plantain, and Fred Rumsey and Mary Gibby of the Natural History Museum the Killarney fern. Laboratory work such as DNA analysis and micropropagation was farmed out to leading museums, botanic gardens and universities. Captive rearing of wartbiters and field crickets became the responsibility of London Zoo. Biodiversity spawned a series of PhD theses on rare butterflies and moths, part-funded by the conservation agencies. Experts were fairly numerous. A species like the oblong woodsia fern had a whole group of enthusiasts hatching plans to strengthen existing sites and bring it back to old ones. Cash is harder to find. The then Environment Minister John Gummer’s hope was that private businesses would rush to champion endangered species in order to advertise their environmental credentials. But relatively few did. At the launch of the first tranche of plans, Gummer could only chalk up a handful of private sponsors. It is noticeable that, while private funds could sometimes be found for skylarks (Tesco) or butterflies (ICI, Wessex Water), it was hard to attract much commercial interest in tiny lichens or weevils. Center Parcs and the Sainsbury Trust have supported some of the plant projects. Perhaps the sponsorship of two water companies and the Environment Agency will cheer up the ‘depressed river mussel’. But most of the money still comes from the conservation world, from the country agencies or the wealthier charities such as RSPB, and even so tends to be channelled towards the more glamorous species.

Attempts to conserve the marsh fritillary butterfly have been largely unsuccessful. Decline has continued through poor management and habitat fragmentation. Releases of captive stock usually fail. Nature reserves are too few and too small. (Natural Image/ Bob Gibbons)

BAP ‘Species Champions’

| Anglian Water Anglian Water/Thames Water/Environment Agency Center Parcs |

Pool frog Depressed river mussel Bullfinch Deptford pink Shore dock Convergent stonewort Lesser-bearded stonewort Slender stonewort Starry stonewort Tassel stonewort Great tassel stonewort Churchyard lichen |

| Co-operative Bank Glaxo Wellcome Frizzell Financial Services ICI |

Bittern Medicinal leech Song thrush Large blue butterfly Pearl-bordered fritillary butterfly |

| Mileta Tog 24 Northumberland Water Shanks McEwen Tesco Water UK/Regional Water Companies/Biffaward Wessex Water |

Stag beetle Roseate tern Corncrake Skylark Otter Early gentian Speckled footman moth Heath fritillary butterfly |

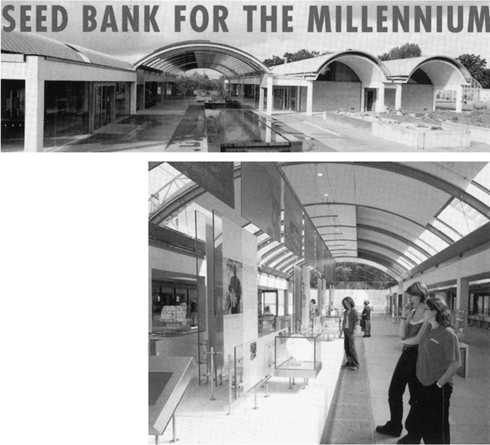

The most important Biodiversity-related project was the Millennium Seed Bank, built at Wakehurst Place in Sussex by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, with the help of the Heritage Lottery Fund and Wellcome Trust. At its heart is a bomb-proof bunker where seeds of the world’s rarest plants are stored in temperature and humidity-controlled conditions. Among them is seed from most of Britain’s native flowering plants, gathered by naturalists during the 1990s, and now available for approved reintroductions and related conservation activities. In the process, the technology for preserving genetic stock of wild species has improved, although a few species with big fleshy seeds are still almost impossible to store (interestingly, the field work showed that certain plants hardly ever produce fertile seed in Britain). The seed bank includes exhibitions devoted to ‘the magic of seeds’ as well as some beautiful ‘wild gardens’ and grounds, and is open to the public.

A second, larger ‘tranche’ of Species Action Plans was published, in four fat volumes, in 1998, ‘the culmination’ (reads the blurb) ‘of many months of work involving Government departments and their scientists, agencies, voluntary conservation groups, owners or managers of land and academic bodies, to set more challenging-but-achievable targets for hundreds of species, large, small and minute’. This time the majority were indeed small and minute. For example, there is Cliorismia rustica, ‘a stiletto fly’, which makes its home on sandy river banks ‘especially where sand shoals have built up at flood level’. Or ‘icy rock-moss’, Andreaea frigida, which lives on boulders irrigated by melting snow, or ‘knothole moss’, Zygodon forsteri, which is confined to rain-tracks on large beech trees furnished from ‘a reservoir held in the trunk cavity’. Even these sound quite catholic in their requirements compared with a ‘pin-head lichen’ called Calicium corynellum, which grows only on ‘the damp, north-facing wall of a church tower in Northumberland’: most of the British population was lost when one of the stones was replaced. For species such as these, ‘action’ consists mostly of finding out more about their distribution and weird and wonderful ways of life – a paid hobby for some solo lichenologist or dipterist. Probably there will never be enough funds to put all these plans into practice. As Nick Hodgetts of the JNCC points out, the plans are really ‘a wish list’. For the more obscure species, survey forms the essential first step, and whether one goes beyond that step depends on whether the beast or plant really is as rare and threatened as was thought.

The Wellcome Trust Millennium Building at Wakehurst Place, home to a British and world seed bank of wild plants, opened its doors in August 2000. (Royal Botanic Gardens)

The annual meetings hosted by the country agencies to review progress on biodiversity were highlights of the conservation calendar in the 1990s. We learned, for example, that helping one species to survive often benefits others. Digging shallow pools for the natterjack toad at Woolmer Forest in Hampshire also helped the woodlark, several rare spiders and an endangered water beetle. Managing downland to create the ‘small-scale mosaics’ required by the wartbiter grasshopper contained useful tips for anyone looking after a grassland nature reserve. Slides of biodiversity in action suggested that conservationists are willing to contemplate fairly drastic action to save a rare species: mechanical diggers, toppling trees, burning reed stubble and bare ground raked by tyres and treads. Much of it tends towards the same end: since many rare species are confined to early seral stages, and become threatened by scrub invasion or dense swamp, saving them is a constant battle against natural succession. Biodiversity action encourages nature reserve managers to do what perhaps they should have done in the first place, to create and maintain ponds, sandy banks, short grass and flower glades. Behind all the details, these occasions created a buzz of excitement quite different from the formulaic aridity of the action plans themselves. With its focus on species, the biodiversity business has helped to revitalise natural history.

Let’s take three examples of work in progress.

Three species

I have chosen three species (or sets of species) with their own action plans to illustrate how these work out in practice. The bittern has one of the biggest budgets of any species, and has become something of a masthead for the whole BAP. The pearl mussel has little hope of attracting the millions spent on bitterns, but in Wilsonian terms it may be a more significant species. Not only does Scotland now hold a sizeable proportion of its collapsed world range, but the mussel may be a ‘keystone’ species without which a whole clear-water ecosystem may find itself in trouble. Finally there are the stipitate hydnoids or tooth-fungi, a group of little-known species that, among other things, illustrate the problems of planning on less than adequate information. Between them they pull into sharper focus some of the strengths and limitations of Species Action Plans in practice.

A boom in the reeds

The bittern is a stocky, brown-streaked bird about the size of a small goose. It lives almost entirely on fish, caught in pools and ditches within dense reed beds. It is a shy bird. At the approach of a human being, a bittern will go rigid, swaying as the wind catches the reeds, with its long neck extended and glaring eyes swivelled forwards. Since they are the same pale brownish colour as the reed stems and fly only with reluctance, bitterns are rarely seen. For that reason, and also to avoid trampling the reeds, bittern surveys are based on calling male birds (although this has resulted in overopti-mistic counts, since bitterns move around and different calling locations may belong to the same bird!). Experienced researchers can recognise individual birds by subtle variations in their eerie, booming call, which fen men called a ‘bottle-bump’.

Skulking in the reeds: the bittern’s hunched, seemingly dejected posture is justified by its recent history in Britain. (HarperCollins Publishers)

The bittern has had a troubled history in Britain. In times gone by they were common enough to appear on the menu at lordly feasts. But their reed-bed habitat was much reduced when the fens were drained for agriculture. Persecution from shooting, egg collecting and the plumage trade even led to the temporary loss of the bittern at the end of the nineteenth century. By the 1950s we had about 80 calling birds, most of them in East Anglia. But then numbers began to fall again: fewer than 50 in 1976, around 25 by 1987, no more than a dozen or so by the early 1990s. What was going wrong for the bittern? Pesticides probably contributed to the initial decline, but the birds went on declining even after the worst pesticides were banned or restricted. The probable reason was staring us in the face in nearly every nature reserve: reed beds were drying out and becoming scrub-invaded. The open reed beds with their fish-filled ditches and pools had been maintained by reed-cutters. Wet conditions are needed to grow good quality reed for thatching, and the cutter also needs a network of broad ditches to navigate his punt. Every time a reed-cutter went out of business another set of reed beds fell into disrepair. Conservationists did their best to step into their shoes, but they seldom did enough. Essentially the poor bittern was running out of places to find fish.

As one of the most endangered British birds, the bittern was an obvious candidate for the first tranche of Species Action Plans in 1995. The circumstances were exceptionally auspicious. Some of its strongest sites were nature reserves. The ‘lead partner’ – naturally enough the RSPB – could bring enviable resources and experience to bear on the project, and workers could also draw on the considerable Dutch expertise in creating wetlands. It also helped that the bittern’s habitat was itself a conservation priority. A further significant factor was prestige. While Britain adds virtually nothing to world bittern numbers – we hold only 0.2 per cent of Europe’s bitterns – British bitterns are nonetheless the best studied in the world, and so we can at least offer expertise. British bittern experts have advised wildlife managers from more bittern-rich EC countries, including Spain, Germany and France. RSPB could not afford to let such a famous bird die out (lest a million angry bird-lovers cancel their memberships). For these reasons, the RSPB went all out to save the bittern.

The battle was fought on two fronts: improving habitat conditions on nature reserves, and creating new wetlands that might attract a passing bittern or two. Creating new and better reed beds is expensive, often requiring mechanical diggers, planting and elaborate ways of managing water, not to mention land-purchase and catchment safeguard. On the other hand, once the ground is wet enough, reeds spread quickly, springing up like rice paddies, often from rhizomes buried in the peat. Part of the RSPB’s own effort went into restoring the reed beds at its famous reserve at Minsmere on the Suffolk coast, the main stronghold of British bitterns, by excavating a series of shallow, bunded lagoons. The bittern responded reasonably well. In 2000, at least seven hen-birds were present in the breeding season, compared with only one in 1990, and Minsmere is once again somewhere where you have a reasonable chance of spotting a bittern.

The plan is also to increase the natural range of bitterns by creating more reed beds. Habitat creation, especially of wetlands, is popular with potential sponsors, for creation and ‘enhancement’ are more exciting words than mere maintenance. English Nature part-funded much of the work on nature reserves, but substantial grants, amounting to millions of pounds, have also come from the Heritage Lottery Fund, the European Union’s Life project and from private businesses. Old reed beds within the bittern’s former range in North Wales are being restored. More reed beds have been created on derelict land, on former opencast coalmines in Montgomery and Northumberland, and in gravel pits at Attenborough, Nottinghamshire. At Wicken Fen, some 70 hectares of reed bed and water are being created in the hope of attracting just a single pair. At Needingworth near St Ives on the edge of the Fens, Hanson Aggregates are to help the RSPB transform a further 1,000 hectares of gravel pits into wetlands over the next 30 years.

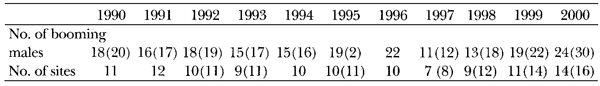

This action plan seems to be working. The overall number of booming males showed only a modest increase from 18 to 24 birds between 1990 and 2000 (see below), after a setback in winter 1996-97 when roughly half of our bitterns died of cold or starvation, or emigrated. The BAP target is 50 birds by 2010. This seems fairly realistic. In The State of the Nation’s Birds (2000), Chris Mead rates the bird’s prospects as good, so long as key reed beds are kept in good repair and there are not too many hard winters. The bittern has also been a useful figurehead for wild wetlands, its well-known stooped, beaky profile attracting funds less likely to be forthcoming for copepods or stoneworts. It also provided a stimulus for conservationists to abandon in-built caution and adopt drastic measures – and they were drastic. It probably needs good nerves – and good public relations – to temporarily convert parts of a famous nature reserve to the appearance of smoking blackboards, or to watch 20-tonne diggers play mud pies with prime habitat. Drastic measures may be needed to undo decades of neglect, but, given the completeness of our reliance on machines, they may also be the only ones available.

‘Booming Bitterns’ in the UK 1990-2000 (RSPB figures)

NB: the figures are conservative; those in brackets are maximum estimates.

Pearls in the river

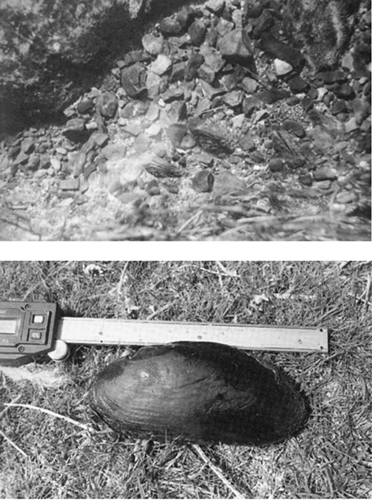

The freshwater pearl mussel, Margaritifera margaritifera, is a quiet, unobtrusive animal that spends its adult life half-buried in gravel in shallow-water riffles in the beds of fast, clean rivers. It looks a little like a dark Roman amphora sticking out of a submerged wreck, the brim and handle formed by the extruding siphons by which the mussel breathes and filters suspended matter from the current, extracting anything edible. The pearl mussel is one of the few species of British animal that may be older than you. They can live for over half a century, and centenarian mussels are not unknown. A single mussel can filter about 50 litres of river water every day. A recent study of a related species in Belgium estimated that the colony filtered water equal to that of a purification plant for a city of 150,000 people (Oliver 2001). What interested our ancestors, however, was not their ecology, but the fat pearls that mussels occasionally produce when annoyed by a parasite or a bit of grit. Unfortunately, fishing for pearls means killing a lot of mussels: you need to open dozens, maybe hundreds, to find a pearl. Even so, they were plentiful enough to support a sizeable, and presumably sustainable, trade (the pearly costumes of Tudor kings and queens owed a lot to Margaritifera margaritifera). In 1861, a German dealer offered to buy all the British freshwater pearls that could be found. Fifteen years later the British pearl fishery had collapsed. A few hardy souls continued looking for pearls in the diminishing number of suitable rivers, such as the Tay or the Spey, but in 1998 the freshwater pearl mussel was legally protected, necessitating a regrettable end to an ancient trade (Cosgrove et al. 2000).

Left: Living pearl mussels in the bed of a Welsh river. Below left: A large mussel, 15 centimetres long and several decades old. (Anna Holmes/ National Museums & Galleries of Wales)

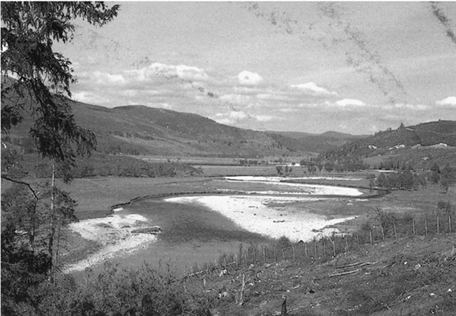

The River Dee near Braemar: one of the last strongholds of the freshwater pearl mussel.

The freshwater pearl mussel is considered to be endangered worldwide. In England and Wales, it is almost extinct – but nonetheless still poached by would-be pearl hunters: a pile of shells photographed recently ‘represented 64,000 years worth of growth’. The last healthy population in Wales, in the Afon Ddu in Snowdonia, was casually extirpated by a land drainage operation in 1997. The clear, soft-water rivers of Scotland are now a world stronghold for the species, but even here serious decline has set in. Out of 155 rivers known to produce pearl mussels in 1990, they survive in only 52, and are still common in only ten. What is killing off the pearl mussel? Pearl fishing is only partly to blame. Much more difficult to tackle are fundamental changes to its environment. Mussels need clear, well-oxygenated water. They are vulnerable to nutrient enrichment, which reduces oxygen and creates silt, which clogs up their siphons and buries them under a suffocating blanket of mud. River engineering also takes its toll by destroying mussel-rich shoals of gravel whenever the river is straightened or deepened. Pearl mussels do not like floods either, which is unfortunate because since the late 1980s Scottish rivers are flooding more often, and depositing yet more silt on the river bed. Mussels also depend on healthy stocks of salmon and trout. Tiny baby mussels drifting in the plankton survive by clamping onto the gills of these fish, where they feed on blood and mucus for a few months, before letting go and starting a new life on the river bed. This behaviour helps, of course, to disperse the mussels. It does not seem to harm the fish, but the falling numbers of salmon and brown trout in our rivers is certainly harming the mussel. Investigators have found ominously few juvenile mussels; superficially healthy looking colonies turn out on closer inspection to consist mainly of geriatric individuals. Without recruitment they are doomed. And without thousands of pearl mussels in their gravel beds, each cleaning and filtering their 50 litres of river water every day, what happens to the water quality?

So what is to be done about it? The freshwater pearl mussel is listed on annexes and appendices of various international conventions and is now protected in British law. Of course, protecting a species without protecting its habitat does not help it much. It does, however, ensure the mussel a place in the BAP. In 1995, a Species Action Plan was prepared for Margaritifera margaritifera, which, as usual, itemised a programme intended to lead to recovery. This is what it amounts to:

- Identify the mussel’s water quality requirements, and ‘seek to ensure that these form the basis for setting Statutory Water Quality objectives’ for mussel sites. (In practice, this means monitoring water quality, which is a process, not preventative action.)

- ‘Seek to ensure that catchment management plans’ and other relevant plans ‘take account of the mussel’. It is hoped that local biodiversity plans will take this forward by ‘encouraging favourable catchment management’. (A bit vague?)

- Designate the best sites as SSSIs and/or SACs. (This doesn’t necessarily help the mussel. It is dying out on SSSIs too.)

- Consider reintroducing them to former sites. (But we do not know how to do this. Every reintroduction attempt so far has been a complete failure.)

- Provide advice to water bailiffs and other water folk and encourage the police to target mussel poachers. (But mussel poachers are not the main problem.)

This rather hopeless list of prescriptions illustrates both the strength and weaknesses of Species Action Plans. On the positive side, they make resources available – in this case, money for survey and research, by which means a lot was learned about the status of pearl mussel and its life-threatening problems through the efforts of Dr Mark Young and his team at Aberdeen University, and Graham Oliver at the National Museum of Wales. Without grants from conservation agencies there would be no research on threatened species in Britain, and without such research universities will lose touch with natural history. On the other hand, it is one thing to elucidate the problems, but quite another to solve them. The SAP for the pearl mussel seeks recovery in bureaucratic terms – more plans, policies and designations – and better policing. But these are all means to a solution without actually being one. The catch-22 is that no plan will work unless the fundamental causes – in this case low fish stocks and dirty water – are addressed, and if they were we would probably not need a plan at all; the mussel would go on looking after itself, as it has managed to do unaided since long before Homo sapiens invaded its watery territory.

Fungi with teeth

Despite their huge diversity and fundamental importance, fungi receive little attention from British conservationists. This may be because experienced mycologists are not, in general, much interested in conservation, while most conservationists are distinctly unenthused by mycology. They are rarely mentioned in formal descriptions of SSSIs except in the most general terms. As yet there is no Atlas of British Fungi, nor an accepted Red Data list, nor is the conservation of fungi high on the priorities of any research institution. There is not even a comprehensive check list of species: the last one was published in 1923 (another is currently in preparation). Yet fungi are incredibly numerous – as the New Naturalist volume Plant Diseases has shown, there are all kinds of pathogenic and microscopic fungi as well as mushrooms and toadstools – more species in fact than all the wild animals, birds, flowers and mosses put together (an average wood may have three times as many large fungi as wild flowers; over 3,000 species of fungi have been found in less than a square mile of Esher Common in Surrey). Without fungi every land ecosystem would collapse; trees would die, soil would choke on its own rubbish and the land would pile up with debris and dead animals. We would probably get by for a while through our reliance on chemicals, but everything else would die out.

In many other European countries, by contrast, fungi are seen as quite as important as flowers or ferns. Conservation in Poland, Denmark, Germany, Holland and the Scandinavian countries is years ahead of Britain, with fungal mapping and monitoring schemes in place, as well as databases, red lists and university research. Probably the reason is that fungi have more commercial importance in these countries than here, and so there are regulations to maintain wild stocks. In Italy, for example, elaborate local laws deter ‘poachers’ from stealing the villagers’ truffles and porcini. In Holland the decline of the girolle or chanterelle has been monitored and mapped, and the reasons adduced from scientific study. But in Britain we do not have the slightest idea whether the numbers of truffles, chanterelles or any other fungi are going up, down or staying the same.

The Biodiversity Action Plan put a few rare fungi in the spotlight for the first time in Britain. After a good deal of list-shifting based on very inadequate data, some 40 species were singled out for conservation action. There was a strong element of tokenism in their choice. The chosen few are mostly large and attractive, relatively easy to recognise and, in some cases, are rare throughout northern Europe. Indeed some were selected because they are rare in other countries. The largest group of BAP fungi are the tooth-fungi or stipitate hydnoids (= stalked hedgehog fungi). As the name implies, they have teeth or spines where other mushroom-shaped fungi have gills or pores. Most of the 15 species covered by the BAP do not have accepted English names, although a recent handbook tried to offer us ‘Concrescent Corky Spine Fungus’ and ‘Green-footed Spiny Cap-Fungus’. Even so, they are quite attractive, with their range of funny shapes, contrasting colours, and, for some species, blood-like blobs of red juice. Some also have the agreeable habit of growing like melting wax, engulfing twigs and bits of grass as they expand.

A ‘stipitate hydnoid’, Phellodon melaleucus or ‘the black and white scented spine-fungus’. It cannot compete successfully with higher plants and requires soil of low natural fertility.

The Species Action Plan thinks it will cost about £55,000 to find out something worthwhile about the stipitate hydnoids. Most of the money has been stumped up by English Nature and Scottish Natural Heritage. In Scotland, a small team of enthusiasts led by Adrian Newton at the University of Edinburgh has systematically mapped their distribution and found out more about their habitat preferences. In England, surveys have been carried out in the New Forest and the Windsor area, the main strongholds of stipitate hydnoids in the south, augmented by a desk survey by myself, pulling together what is known about them, and what needs to be known before we can conserve them properly (Mistakes will happen. The best site in the New Forest was damaged by felling in 2001). The Plan also speaks of ex situ cultivation of one stalactite-like species, Hericium erinaceum, to produce material for translocation attempts (the BAP shows a faith in translocations and reintroductions that is not often justified by results).

Where has all this survey taken us so far? First, we discovered that none of the 15 are as rare as they were thought to be. This is interesting: their red-listing was based on their status in the Netherlands and other European countries, not in Britain. We also have a much better understanding of the kinds of places they like: wood banks, the sides of tracks, stream banks, even old sandpits, usually in long-established woodland of oak, sweet chestnut and Scots pine, often, but not always, on free-draining, acidic soils. It seems they like rather arid soil, where there is less competition from grasses and other tall vegetation. They always occur near trees, but not necessarily mature trees. It may be that they survive because areas on light infertile soils were often preserved as woods, parks or commons. Their relatively healthy state in the Scottish Highlands mirrors that of Norway and Sweden, where they are also still frequent.

Low-power, low-budget survey work like this often produces incidental, unplanned benefits that may outweigh the original aims of the project. In this case, it gives Britain’s growing band of competent field mycologists a project to get their teeth into (not meant literally, though many of us do indeed enjoy the comestible side of our hobby). It also flags up a group of fungi that tell us things about fungi in general, for example, that mycor-rhizal species (those that grow on the roots of plants, especially trees) are sensitive to chemical pollution, especially active nitrogen. They also form another good reason for preserving wood banks and natural woodland soils, and restoring woods infested with rhododendron. A further benefit is that it helps to build bridges between the hitherto separate worlds of mycology and conservation, and may even help to secure a higher priority for mycology in scientific institutions and conservation work. Perhaps the ‘concrescent corky spine fungus’ may one day be as familiar as a prickly pear or a hedgehog.

Biodiversity replicated

The 1990s saw a considerable outbreak of biodiversity planning, particularly among local partnerships, where local knowledge and skills help ‘to deliver national biodiversity targets’. These are known as Local Biodiversity Action Plans or LBAPs. The lead has been taken by planning departments, with the help of the conservation agencies, and often involving others in a formal partnership. For example, the LBAP for North-east Scotland enjoys the support of a government department, three local councils, the National Farmers’ Union of Scotland, Aberdeen University and ‘an education consultant’, among others. It is ‘a locally-driven process’ with a slogan: ‘people achieving local action for their local wildlife’. What it boils down to is a commitment by communities to look after their wildlife, with special reference to species and habitats that contribute to the local character. The plans highlight an area’s special wildlife and landscape qualities, and the action needed to conserve them. For example, the Leeds LBAP recognises the value of its remaining hedgerows and field margins (‘a critically important habitat type for many once-common birds’), reed beds and magnesian limestone grassland (‘only a handful of small, isolated fragments left’), together with their threatened bats, crayfish, pasqueflowers and harvest mice. The Edinburgh LBAP proposes special action for swifts (‘prepare development-control guidance on provision of nest spaces in new development’) and cornflowers (‘include cornflower in specifications of seed-mixes for annual meadows created as a condition of new developments’). Such action is largely voluntary, although it could be, and in some cases has been, made a planning condition for new developments. In the view of the Commons Committee reviewing Biodiversity progress in 1999, local wildlife sites should be registered, and planning guidelines revised to ensure that ‘there is a general presumption against development on these sites unless no suitable alternative can be found’. Many LBAPs are accompanied by glossy booklets with enticing pictures of wild flowers and healthy habitats – lessons in local biogeography, with a display of ‘biological correctness’ thrown in.

Are Biodiversity Action Plans working?

By 2000, 436 species action plans had been prepared. However, only a minority had been put into practice, and it is too early to judge their overall effectiveness. For the record, however, the Biodiversity Challenge Group assessed the interim results as follows:

The status of BAP habitats and species

| Habitat plans | Species Plans | |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient information | 8 | 17 |

| Declining | 1 | 11 |

| No change | 0 | 13 |

| Signs of recovery | 5 | 17 |

| Recovered (i.e. targets met) | 0 | 0 |

| ‘Lost’ | 0 | 1 |

The lost species is Ivell’s sea anemone, which is presumed extinct in Britain, a species that just missed the Biodiversity bus.

The fact that not a single target has yet been reached (2001) suggests that, even with the right kind of action, species and habitats take time to recover. Most ‘signs of recovery’ so far were due not to a real increase, but to better survey effort. For example, the early gentian, Gentianella anglica, is deemed on the way to recovery not because of what anybody did, but because several large new colonies turned up in the course of investigation. Interestingly, recent molecular analysis at Cambridge suggested that the early gentian is not a species at all, but an endemic early flowering form of the common autumn gentian (though whether that means it is not worth bothering about any more, I am not sure). It has proved easier to help species restricted to a particular habitat or geographical area, such as stone curlew or cirl bunting, than widespread ones such as skylark or song thrush. You can target cirl buntings with a special agri-environment scheme (see Chapter 6), but to stop skylarks declining you need to address fundamental agricultural policy.

Conservationists have tended to talk up the BAP in non-scientific terms. It has kept conservation groups focused on goals. It has helped to promote the health of the natural environment as a national goal, comparable with health and education. It involves parts of the community hitherto on the fringe or looking the other way, such as public utilities and businesses. It has provided a new focus to the way the planning system addresses wildlife and nature conservation issues. In their review, Biodiversity Counts, the voluntary bodies claim that Biodiversity delivers a better ‘quality of life’ by promoting environment-friendly policies: ‘The greatest challenge is [in] greening government policy: for access, the economy of rural areas and people’s health and quality of life.’ By means of a hive of talk-shops and a mountain of plans, the Biodiversity industry has capitalised on public opinion, brought nature conservation more firmly into the national agenda, and produced more co-operative ways of working.

The relatively few species confined to Britain have evolved in isolation, probably during the past 10,000 years. This means they are only slightly different to their closest relatives. This is one of them: Marshal’s eyebright, Euphrasia marshalii, confined to the coast of northern Scotland and so vulnerable to climate warming. Should the preservation of endemics be a conservation priority? (Natural Image/Bob Gibbons)

Is there a downside? According to Biodiversity Counts, some departments and agencies have engaged with the BAP more than others. High marks are awarded to the Environment Agency, English Nature, the Forestry Commission and environment departments in Scotland and England. On the other hand, cabbages are offered to agriculture departments, the water regulator Ofwat, NERC and the Home Office for their lack of zeal. More importantly, perhaps, the BAP has so far shown only limited benefits for wildlife. It has not yet rescued a single species, nor has it stopped further declines from happening, even among much-loved animals such as the skylark or the water vole. Another, rather obvious concern is that Biodiversity may soon sink under its own bureaucratic weight. Some fear the process is promoting a species-centred approach to nature conservation which is wasteful and logistically daunting. Taken to its logical extreme, the BAP would require hundreds of intensively managed nature reserves, and intrusive means such as translocations which, if widely adopted, would blur the boundaries between conservation and gardening. It is possible to argue that conservation BAP-style rather misses the point. In a long-farmed environment like Britain, most species have adapted to traditional forms of human husbandry and harvest. There would be no need to address the plight of individual beetles or mosses if we managed the land sustainably and did not pollute the environment. By trying to help some declining beetle or bug, we are therefore addressing a symptom rather than the cause. Biodiversity planning appeals to those, perhaps the majority of conservationists, who are wrapped up in the means to an end and feel at home in the planner’s world of plans, targets and zones. What one misses in all the literature devoted to it is any readiness to stand back from the details and look at where this self-replicating mountain of plans may be taking us.

Threats to listed Biodiversity habitats (from Biodiversity Counts (2001))

| Type of threat | Number of habitats threatened |

|---|---|

| Land use change | |

| 1. Habitat destruction | 31 |

| 2. Agricultural intensification | 27 |

| 3. Lack of appropriate management | 21 |

| 4. Habitat fragmentation | 17 |

| 5. Water abstraction, drainage or inappropriate river management | 16 |

| 6. Coastal development and management | 16 |

| 7.Changes in agricultural management | 13 |

| 8. Afforestation | 13 |

| 9. Changes to woodland management | 5 |

| Environmental pollution | |

| 10. Climate change/sea level rise | 19 |

| 11. Water pollution | 18 |

| 12. Air pollution | 13 |

| Other | |

| 13. Recreational pressure | 13 |

| 14. Fisheries management | 13 |

The skylark: not only a biodiversity target species but a government indicator of the quality of our lives. (Nature Photographers Ltd)