The voyage of the Chidambaram to Penang and Singapore was an uneventful glide over submissive blue waters. She had formerly belonged to Messageries Maritimes, and had plied between Dunkerque, Le Havre and the Canaries. Since her maiden crossing of the Bay of Bengal and the Malacca Strait in 1973, she had carried hundreds of holidaying Malay and Indian students, workers and businessmen back and forth with stabilized aplomb.

There had been a rampage when Madrasi students ran wild, assaulting passengers, throwing chairs overboard, even stripping a girl or two – so terrifying them, the purser told me, that they wanted to jump overboard. But the leaders of the rampage had been handcuffed in their cabins and later fired from their university, and on subsequent voyages peace had become the rule. ‘I know students who are barely literate,’ the purser said contemptuously.

The captain sent me a message that I was welcome on the bridge any time I wanted to see the charts. Of the same school as Bala and Dennis Beale, he knew and loved the Andamans, especially for the fishing. He told me all this the first afternoon, and showed me the bridge, wide and deep like that of the Patrick Vieljeux.

‘No brass fittings,’ I noticed.

‘Brass is a thing of the past.’

‘Bala’s got a lot of it on Nancowry.’

‘Oh, yes, there.’

Captain Sujit Choudhuri lived up to the standards of no-nonsense friendliness I had come to expect from Indian masters like Dennis Beale, Bala and John. In fact, now that I think about it, I found this quality in all the masters I met between Cyprus and Singapore. It is as if ships’ captains live at some isolated level of self-assurance, philosophically removed by a life sandwiched between sea and sky from the landlubberly pettiness of the rest of us. The wide world must contain petty ships’ captains, but I have yet to meet one. Perhaps the reason is contained in Joseph Conrad’s remark that, ‘of all the living creatures upon land and sea, it is ships alone that cannot be taken in by barren pretences, that will not put up with bad art from their masters’.

*

I spent a considerable time reading on this leg of the journey. I had a cabin to myself and, although the ship was quite full, its saloons were usually empty and the Muzak was muted. The French decorator employed by Messageries Maritimes had done something bizarre to a main wall of the largest saloon, transforming it into a massive tableau of a frozen city of unreal turrets, weed-filled streets and ghostly ships at leprous wharves. This romantic nightmare he had underscored with a quotation from Baudelaire:

Cette ville est au bord de l’eau

On dit qu’elle est bâtie en marbre….

Voilà un paysage selon ton goût;

Un paysage fait avec la lumière et le minéral,

Et le liquide pour les réfléchir….

It was an unexpected picture to come across in the Bay of Bengal. It struck me even more oddly in the evening when the reading room and saloon became alternately a cinema and a miniature casino where, surprisingly, two British girls presided over games of blackjack. The brittle lights of the fifties décor twinkled happily, a group of mountainous Parsee ladies and gentlemen whooped with high spirits and laughter, and the comforting clink of glasses came from the bar. A pop song that throbbed from speakers over a small dance floor had an unusual title: ‘Save All Your Business for Me’. Above all this the crumbling turrets and spectral quays of that inappropriate mural seized the attention and chilled the heart.

A middle-aged Australian couple travelling back to Adelaide had been touring Afghanistan in a minibus for some months. ‘You could stand up in it,’ she said, ‘although it had no fitted things. I mean, I had to use a plastic pot, but I managed. We’ve taken it all over the world.’ Near Hunza or Gilgit in Pakistan’s extreme north, they had been attacked by tribesmen and badly beaten up, but they told the story as a joke.

‘Bob loves anything mechanical,’ she told me. ‘He’s got a beaut bike he can’t wait to get home to. He rode it from Sri Lanka to London in 1952.’

Later I was talking to Bob when she came up laughing and said, ‘I’ve just been in the loo. Do you know, a man tried his best to join me while I was squatting in there. When I came out, I found he’d peed in the washbasin.’

‘Who was it, then?’

‘One of those Kurds.’

There were indeed three Kurds aboard the Chidambaram. Later I tried to talk to them in mangled English, French and Arabic. They were a thick-set, blue-chinned trio. ‘You are from Germany?’ they asked.

‘No, England.’

‘We are Kurds,’ they said gruffly.

When I asked them who they preferred, the Shah or Ayatollah Khomeini, they answered, ‘Both are bad. The Shah is looking too far forward, Khomeini too far back – he wants to see 700 AD in 1980.’

They were Kurdish nationalists, they said, and were confident that one day their country would be united and independent. ‘There are problems but in fifteen, twenty years….’ Were they, I wondered, on an arms-buying mission?

They bought bottles of Teacher’s whisky from the bar and drank fiercely, toasting ‘Kurdistan or death’. I never discovered which one had peed in the washbasin in the ladies’ lavatory, or what they were doing crossing from Madras to Singapore on the Chidambaram.

*

Sheltering behind the funnel, I read copies of Harry Miller’s ‘Speaking of Animals’ columns in the Indian Express. In one on whales, he quoted Hilaire Belloc:

The whale that wanders round the Pole,

Is not a table fish.

You cannot bake or boil him whole,

Nor serve him on a dish.

In another column, Harry considered the large forms of squid, a creature which, even more than snakes, fills me with revulsion. He wrote:

Attacks on boats appear to have been made by giant squid, but even the largest come nowhere near the size of the monsters depicted in some old prints. However, such stories have given rise to many legends, such as the persistent Scandinavian belief in the Kraken, a colossal sea monster measuring two kilometres in diameter with mast-like arms capable of dragging the largest ships down into the sea.

The combination of whale and giant squid jogged my memory about an old sailor’s story that had impressed me some years before, and I looked it up again in a book by Sir Francis Chichester called Along the Clipper Way:

A reliable eyewitness of what happened said later that near Sumatra in the Indian Ocean, something he thought might be a volcano lifted its head above the sea. It was a large sperm whale locked in deadly combat with a cuttle-fish, or squid, whose tentacles seemed to enclose the whole of his body. The eyewitness, Bullen by name, estimated the mollusc’s eyes to be at least a foot in diameter. The silent struggle ended when the whale clamped his jaws on the body of the squid and ‘in a businesslike, methodical way’ sawed through it.

I quickly scanned the sea. After all, we were in the waters north of Sumatra where Bullen had witnessed this spectacle, and it seemed uncomfortably close to my nightmare. But the sunlit waves winked innocently back at me.

*

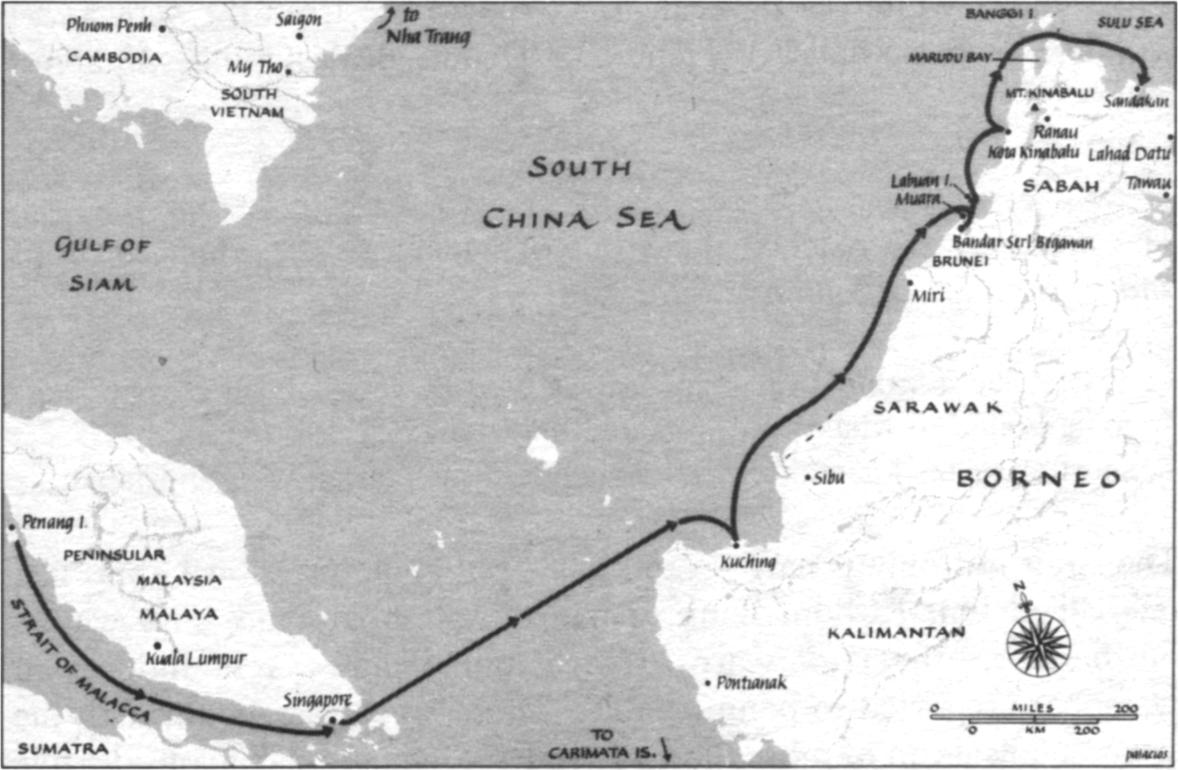

I went ashore only briefly in Georgetown on Penang Island, but the beauty of South-east Asia struck my eyes with the full force of an old love suddenly revived. I suppose to the superficial eye the landscape on Penang is almost the same as that in Tamil Nadu, the Tamil state in southern India more than a thousand miles away, but it is not. There is as subtle a difference in the size and shape of the simple buildings, in the appearance and arrangement of trees, and in the rig of native craft in a bay as there is in the colour and physiognomy of men.

I passed through Georgetown’s customs office, showing my passport to big Sikhs in boastful turbans, and wandered down the Pesara King Edward, stopping to take in the orientally domed ochre and cream clock tower presented to Penang by Cheoh Chen Eok ‘in commemoration of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee’. I admired the olive and white pillared and porticoed colonial buildings; there is nothing overbearing about them. A parade of Malay Muslims chanted ‘Allahu Akbar’ on the Padang, and I ate a plateful of flower crabs at the Anchor Bar of the handsome old Eastern and Oriental Hotel, a small version of Raffles in Singapore, and one of the great hotels of the East. A young European tourist came in from the garden wearing a dressing gown and a white plastic beak to save his nose from the sun, and I wondered what Khalat or Hentry or Dennis Beale would say about that.

*

The next day we reached the Strait of Malacca. The Malacca Strait and East Coast of Sumatra Pilot said:

The Malacca Strait is the main seaway used by vessels from Europe and India bound to Malaysian ports and the China Sea. It provides the shortest routes for tankers trading between the Persian Gulf and Japan.

The strait not only is narrow and busy, but contains critical areas like one called One-Fathom Bank, a menace of shoals and sand waves. Furthermore, the Pilot warns, ‘Navigational aids … in Indonesian waters are reported to be unreliable.’ Thus, ‘since passage through the strait entails a run of more than 250 miles, long periods of considerable vigilance are necessary in order to maintain safe standards of navigation’. Nothing could be more blunt than this warning.

Captain Choudhuri talked about collisions in the strait. ‘There are quite a few unreported – if it’s just two ships grazing or bumping and no one hurt. In the latest the smaller ship went down. Luckily, no one was lost.’

Like the Strait of Hormuz or the Suez Canal, the Malacca Strait is a funnel of the sea world where the appalling vision of colliding supertankers is a distinct possibility. There are smaller hazards, too. The water was dotted with tiny Sumatran or Malaysian motor trawlers, seemingly contemptuous of our approach, which chugged across our bows and sometimes made us change course.

‘The trouble with them,’ said Captain Choudhuri, fixing his glasses on them severely, ‘is that the crew are often asleep, tired from their hours at sea, so they don’t look.’

The sea traffic had relatively the same density of a weekend city street. A Panamanian freighter passed so close to us that without glasses I could see a man leaning on the rail in a red bathing suit, a man in a hammock dangling a leg, and another, squatting on the deck, slicing a watermelon.

Opposite Malacca, the coast of Sumatra pushed east and narrowed the channel still more. A white octagonal tower on piles signalled One-Fathom Bank. The coast is described by the Pilot as ‘mostly muddy, low-lying and uniformly covered with mangroves’. But on my side of the wing of the Chidambaram’s bridge there was nothing to be seen save for a slight smudge.

The radio began to bark and whine; magnified human voices chattered irritably, and babel invaded the bridge.

‘Listen,’ said Captain Choudhuri. ‘One ship’s captain is complaining that another ship has hit him and gone on regardless. A hit-and-run. And they’re all speaking different languages, so no one is understanding the others. A real mix-up.’

As a vision from the sea, Singapore is still exciting. Stamford Raffles’s creation remains a great Eastern port. The sweep of its anchorages, the graceful green frontage of the Padang, the white dignity of St Andrew’s Cathedral and the pillared public buildings behind, even the cluster of very new skyscrapers – all have grandeur. The city has supermarkets, too, but it is still the East. I seem to see a signpost here – a fantasy, of course – reading, ‘From here on is the East – behind you, the Rest of the World.’ The long elephant’s trunk of Malaysia and the spray of islands at its tip form a screen between the wider world and the concentrated Orient.

The western approach to the Empire Dock is the inner one curving around to creep inside these islands. A strong tide went past us towards the hazy Rhios Islands to the south. Overhead, like a schoolboy’s paper aeroplane, a British Airways Concorde lowered her conical nose – just like the plastic beak on the tourist’s nose in Penang – for landing. I had no desire to be up there looking down on the Chidambaram heading for her familiar resting place, moving over an obedient sea. As we docked I saw from her rail Dennis Bloodworth waving on the quay.