It was a simple idea: take a series of ships of many sizes and kinds; go where they lead for a few months; see what happens. It was an adaptation of the old idea of Running Away to Sea, a boyhood yearning bred of

tales, marvellous tales

Of ships and stars and isles where good men rest.

No doubt my dream of the sea was born during the long summers I spent as a child in what I still think of as the oldest-feeling, most soul-subduing and cosily creepy part of England, the part almost hidden between Britain’s battered kneecap and shin. I mean, to be more exact, between Devon’s Hartland Point and Cornwall’s Fire Point Beacon above Boscastle, around the tiny harbour and old stone breakwater of Bude Haven. This is the Wreckers’ Coast: a place of buzzards and seals and effigies of knights in dim, half-lost churches, where seas pound into cliffbound bays that have swallowed seamen from a hundred wrecked schooners and, in wartime, perhaps harboured German U-boats.

Once, poor Cornish children in these parts prayed, ‘God save Father and Mother and zend a ship to shore vore mornin.’ And on cold, rainy days there always seemed to me to be an aura here of doomed ships and silent watchers on terrible cliffs – an aura that survives today’s asphalted roads and trailer parks. Yet in the summer sun it all looks quite different. Everything smiles on picnickers, surfers, flower gatherers and adventurous walkers with bird books, haversacks, sandwiches and hip flasks.

Under the sun, these cliffs give almost theatrically splendid views. South of Bude between Compass Point and Widemouth Bay’s Black Rock (actually, the locals say, a Cornish giant eternally plaiting ropes of sand), my grandmother years ago would jerkily brake the Austin two-seater and exclaim, ‘What a lot of sea!’ My grandmother’s house stood back from the sea but on a rising slope of land, so that from my bedroom window I could see the gleam of the Atlantic Ocean over the rooftops of other houses. The attic of the gaunt and ugly Edwardian house smelled of damp floorboards, old suitcases and mouse droppings, but it was dark and large – ideal for hide-and-seek – and full of books, some of which had been my father’s when he was a boy.

I spent hours up there delving into Robert Louis Stevenson, Jack London, Captain Marryat, R. M. Ballantyne and a Cornish writer of the 1920s called Crosbie Garstin who wrote exciting books about wreckers and smugglers on this very coast. Obsessed with the doings of Long John Silver or the Swiss Family Robinson, I was almost convinced that one clear day I would see on the horizon the Indies … tall ships … Hispaniola … Cathay. ‘Fifteen men on a dead man’s chest,’ I would growl menacingly at my older sister, who would shrug and make herself scarce.

Even today, when I revisit Bude, this conviction sidles up to me like Blind Pew to Billy Bones. The cliffs there are as high as seven hundred and twenty feet, the waves relentlessly pound against them, larks and hawks move restlessly above, and the biggest gulls I’ve ever seen strut with eyes as cold as the sea below. The coastline here is a chain of tall headlands with names like Cow and Calf, Sharpnose Point, Wrangle Point, Longbeak, Dizzard. Their angry shapes and the prevailing westerly winds have done for dozens of ships, provoking the sailors’ saying:

From Trevose Head to Hartland Light

Is a watery grave by day or night.

At the Falcon Inn in the old part of Bude, Desmond Gregory, the pub owner and a pillar of the hard-working Bude lifeboat team, lets off his signal rockets outside the pub if a boat is in trouble in the bay. Old photographs of spectacular wrecks adorn the walls of his bar; I have one of my own at home of the Austro-Hungarian barque Capricorno, her sails in tatters, her skipper drunk (so history books relate), being pounded to pieces by enormous seas below Compass Point in December 1900. Only two men were saved. In the picture, a solitary seaman stands on the doomed deck like Steerforth in David Copperfield.

Sailing ships regularly used Bude as a port of call up to 1936; I remember a locally famous ketch called Ceres and old bewhiskered sea captains strolling around the harbour.

All this contributed to my dream of adventure and sea travel that this book represents. It also gave me a sense of the past, for Bude is ennobled by its cliffs, its thundering surf and its eerie hinterland. Even now, visiting the place after an interval of time, I am startled by the sheer age of the region. You can ramble for hours across headlands that run back forming broad, high land on which scattered farms seem settled hull down in wriggling lanes to escape winter gales that have forced the trees to grow almost parallel to the earth. In long, deep valleys you come across small, ancient churches oddly far from any village, and smelling of flowers and grass. Huge trees loom over their tombstones, under stone canopies armoured effigies turn up stone toes, and fine old wooden pews are fighting erosion by age or the death watch beetle. On the gravestones the same names appear over and over, century after century: Mutton, Sleeman, Oke and Prust. Frequent Christian names here are Eli, Caleb, Joshua, Reuben. As a boy, I was particularly fond of a clifftop church at a village called Morwenstow because it had a ship’s figurehead in its graveyard, and because a once-famous and eccentric vicar is buried there. Parson Hawker (‘Passon’ was how the locals pronounced it) ate opium and wrote outrageous poetry when he wasn’t burying drowned sailors between 1834 and 1878. He was a practical joker, and one moonlit night he clambered on to a rock to impersonate a mermaid. In a book of the time, a Bude man was recorded as saying of this scene, ‘Dressin’ up in seaweed and not much else, and combin’ his hair and zingin’, till all the town went down to see ’un, they thought ’twas a merry maid [mermaid] sure enough.’ Then the ‘Passon’ scared the daylights out of his audience by standing up on his rock and singing ‘God Save the King’.

If a cloud covers the sun in this old region of England, you may feel suddenly uneasy. As a boy, I was sometimes glad to get back to the life of Bude’s wide sandy beaches, where young men surfed, children’s nannies helped to build sand castles, and hysterical dogs tried to dig their way to Australia. Kids with kites would shriek when their mother capsized in a shrimp pool (‘Oh, Ma, you’re showing all you’ve got!’) while I sat by myself nursing my dream of far places among the long black lines of rock, knobbly with mussels and limpets, like arthritic fingers, running out into the booming surf.

Years passed before the dream achieved the least substance. This happened not long before my eighteenth birthday, when a school friend and I walked through the dead of a misty night to board a ship at a wharf in Fowey, a small Cornish river port. My friend’s father had arranged with the shipowners for us to be signed on to a 500-ton coaster, the Northgate, out of Hull. A modest adventure, a short voyage up the English Channel to the Scheldt and Antwerp, but at that age it was as exciting as a round trip to Hispaniola and the Spanish Main.

We went down to Fowey in January, the month some sailors refer to as ‘between dog and wolf’, and it was one of the wildest Januaries for years. The berthed ship seemed as dead as an icicle. I can still hear the ring of our hesitant heels on the freezing metal deck, our whispers in the dark, and at last the wavering cry of ‘Who’s there?’ from the skylight, before the white, balding head of the ship’s cook, a kind, brusque old man, emerged from the companionway.

I remember thinking that the Northgate seemed disconcertingly indifferent to our arrival. How could that be when we had dreamed about her for weeks? I didn’t know then that a ship only wakes up and pays attention to those on board when she’s at sea.

In the morning sunshine things seemed different, of course, not alarming at all. The captain was a friendly Yorkshireman, and the crew took our presence on board as a bit of a joke. We had signed on as ‘deckie-learners’, and I suppose we polished the brass and swabbed away the china clay that had clogged the decks during loading energetically enough to satisfy them.

A short trip, but it was the year of record gales in the Channel and we rode one of them out at anchor in a fleet of other ships off Dungeness on the Kentish coast. The Northgate was unduly long for her width and plunged about abominably – so abominably, in fact, that the captain and all his officers were seasick. A radio battery in the messroom broke loose, and its acid burned awkward holes in my corduroy trousers. I remember my relief at not being sick, and the captain’s white face, and offering him a Capstan cigarette and my pride when he said, ‘Thanks moochly, Gav.’

At Antwerp, although the city was still in ruins from the air raids in the war which had not long ended, we were allowed ashore escorted by Andie, a diminutive deckhand of about my age. In a deserted square near the bombed cathedral, Andie trotted confidently over to two tarts on a corner. He chose the taller of the two – at least a foot taller than himself. On the cathedral steps he had to stand one step above her, and for a moment he even lost his footing. Later he boasted, ‘You’ve never seen that before,’ and we had to admit we hadn’t. He also boasted that he’d had syphilis and the quack had poured mercury up his penis. God knows if it was true; we’d have believed anything then.

That short trip marked me as much, perhaps, as the mercury marked Andie. For years I dreamed of taking a much longer sea journey, but travel and war reporting intervened. Only recently did the possibility occur, and by then it was almost too late.

Almost too late, that is, to find any ships. Working one’s passage is difficult – impossible, perhaps – in these strict days of unions and unemployment. Passenger travel, as I was to discover, is moribund. Nevertheless, I set about finding out what would happen to someone who tried to port-hop to some far destination on the other side of the world. (The end of the line, I thought, could be a port in China – Canton, say; Canton would do.) Surely, it must be possible. How could sea travel be dead?

I could have taken a long cruise, but I ruled that out; I didn’t want to travel long distances on a single ship. I wondered how travel agents would react to the sort of hop-skip-jump I had in mind, and when I tried a couple of them I found discouragement.

‘It’s impossible. Even for a single gent, it’s utterly impossible.’ The middle-aged travel agent ran a finger delicately across his left eyebrow and organized a mouth that might, twenty years before, have been described as ‘rosebud’, into an apologetic smile. ‘So my answer, I’m ever so sorry to tell you, is rather simple: “No can do.”’ He lightly dabbed his lips with a handkerchief he took from his sleeve. He wore a puce knitted tie that looked like a hairnet.

He had been affability itself when I first came in, but when I told him what I wanted I saw at once that I was going to spoil his day.

‘By sea? Oh, dearie me, that’s a poser, that is. Well, let me just think. A single gent, from Europe to Macao, all on your own? I’m not even sure how I’d set about it. You’re a dying breed, you lone travellers – you know that, I suppose. It’s all groups now, you know. Frankly, on your own, you’re more of a nuisance than anything.’

He looked me over without enthusiasm. ‘A group, I’d know how to handle you. I mean, I can arrange a nice long tour for a group of old biddies, with exciting stopovers – well, quite exciting. But you? I might be flipping through those enormous shipping lists until the cows come home and still not have accommodated you in the way you fancy. Frankly, my time’s limited and I must ask myself, is it worth spending it on this single gentleman? Nothing against you personally, of course.’

I rose to go.

‘It’s modern life,’ he said. ‘You’ve asked me for the utterly impossible, and my simple answer is: “No can do.”’

His dismissive ‘Cheeri-bye’ followed me out.

At Thomas Cook’s in Berkeley Street a sensible, much nicer man, Mr Bert Chattell, a former Cook’s tour courier, was equally pessimistic.

‘The trouble is, the traditional British sea routes to the Far East and across the Atlantic have disappeared because of rising prices and cheaper air travel. Prices – that’s it in a nutshell. Now there’s only P&O to Australia and New Zealand, and round the world now and again on a limited scale.

‘I can’t for the life of me think of any boat going south of the Med. Nothing springs to mind there. In the old days, of course, well…. There’s Polish Ocean Lines, they go from Gdynia to Antwerp, and from there to Port Said, Singapore and Hong Kong, Japan and back again. But not, I think you’ll find, on a schedule. You can never tell what delays there’ll be.

‘If someone came up to me and said, “Book me round the world now,” I couldn’t do it. Not on a series of ships, I mean.’

Not encouraging. But there must, I thought, be some way, however erratic, to travel by sea to Asia. I refused to believe it was impossible.

I telephoned the P&O Lines people in the City of London, but the news there was also depressing. P&O have cruise ships, they said, but nothing that would interest me.

A call to Swire & Sons, one of the biggest British trading and shipping companies in the Far East, brought an invitation from John Swire, head of the giant British group that includes, among much else, the China Navigation Company in Hong Kong. ‘Come and lunch,’ he said.

Swire’s is big and grand. Grand enough and old enough to have accumulated traditions and a book or two of imperial history. Tycoon is a Japanese word (taikun). The Swires are tycoons. At Regis House (big but not grand) in the City near London Bridge, an elderly servant opened a door and said, ‘For Mr John Swire? This way, if you please, sir.’ Beautiful, meticulously constructed models of Swire ships past and present stood along the walls in glass cases. A collection of old ship’s bells lay in a row like the skulls of warriors in an African burial cave. I was looking at a bell inscribed with the name Hupeh and the date 1937 when John Swire, a towering, soldierly figure, came up. ‘That’s the old Hupeh, not the one we’ve got now,’ he said. Several months later I sailed from Manila on the new Hupeh and thought back to this old bell.

‘We have practically no cargo–passenger ships in the East,’ John Swire said at lunch. Swire’s cargo ships were still active between Hong Kong, Taiwan, China, Japan, the Pacific islands, Australia, New Guinea, the Philippines and Singapore, but air travel was taking over eastern passenger routes; the Swires themselves owned the airline Cathay Pacific. If only, he said, I had tried to do this ten years ago….

Nevertheless, he was helpful, willing to provide a safety net if he could. He would write to his offices throughout the East, asking his managers to look out for me and help where possible; I might need any help I could get if I was to avoid being stranded for weeks in some godforsaken place. Swire’s also had an operation in the Gulf, he added – tugs working with offshore oil rigs, that sort of thing. Might be interesting.

Afterwards I walked out into King William Street and hurried past the quick-sandwich shops, the window full of telex appliances and the doors of Christian missionary societies, and took a tube to Green Park. In Cook’s, kind Mr Chattell gave me a shipping list, the ABC Shipping Guide, and like a squirrel with a nut, I carried it home and devoured it.

About half of its pages was devoted to cruises: no good to me. The other half showed that people who wanted to move about between small collections of islands, or from one port to another one nearby, faced no problem. If you felt a burning desire to travel by sea between, say, Gomera and Tenerife in the Canaries, you could easily do so; if a sudden impulse drove you to cross from Cape May, New Jersey, to Lewes Ferry, Delaware, the Delaware Bay Service was daily at your disposal for a small charge.

On other pages, long-distance round trips on large cargo–passenger ships were advertised. Farrell Lines, for example, would give you a round trip from the United States to South Africa and back again; the Moore–McCormack Lines would take you from New York to Cape Town to Dar es Salaam to Zanzibar and back every three weeks. Lykes Brothers Steamship Company would take you on a round trip to Japan. There were others, but none offered the flexibility I needed.

By now it was obvious that I must play the trip to Canton by ear. There was no point in relying on elusive dates and problematical itineraries of ships subject to whimsical change. I would take what came along the way, trusting to luck that any delay would not be horrendously long. I had taken leave of absence from the Observer, telling Donald Trelford, the editor, that the journey shouldn’t take me much more than four months; that seemed a longish time as I pored over my maps in London. I would board any vessel moving in the right direction: a tanker, a freighter, a dhow, a junk – anything. Nothing that went too far at one time; that would reduce the number of ports of call – and I wanted to see a good number of ports.

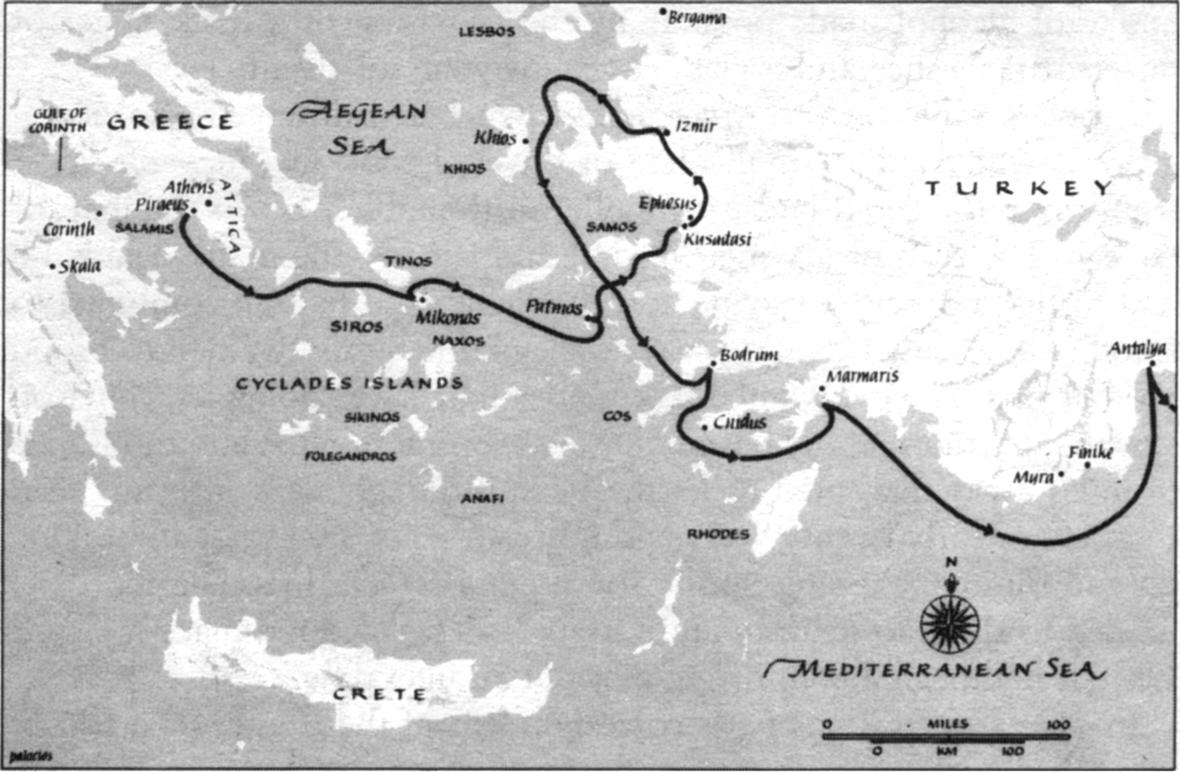

I was embarking, in fact, on a game of traveller’s roulette. I bought a cheap atlas and marked with a ballpoint pen a number of ports either because I liked the sound of them or because I’d been there before as a foreign correspondent: Smyrna, Alexandria, Port Said, Suez, Jedda, Dubai, Karachi, Bombay, Cochin, Colombo, Calcutta, Madras, Singapore, Brunei, Bangkok, Manila, Hong Kong, Macao, Canton. As an afterthought, though without much hope, I added the Andaman Islands, in the Bay of Bengal; the sombre vision of a tropical penal settlement and sudden and agonizing death from native poisoned darts had lodged in my mind since my first reading of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes thriller The Sign of Four.

Where should I start? I went back to the lists again, but the decision was soon made. Not Rotterdam or Southampton; the Channel and the west Mediterranean were well known and well travelled. I would start in Europe, but as close to Asia as possible: Athens. Friends had told me of a steamer that shuttled passengers from Piraeus to the Greek island of Patmos, near Smyrna in Turkey-in-Asia. From there I could find my way slowly to the Suez Canal (even then the canal looked like a Becher’s Brook, a first and formidable major hurdle).

That decided, I booked a flight to Athens and began to gather together the things I would need on a sea voyage of indeterminate length.

Notebooks, ballpoint pens and books were the first requirements. Conrad’s Under Western Eyes and Mirror of the Sea, Ford Madox Ford’s Memories and Impressions, a handful of thrillers, Joseph Heller’s Good as Gold, Vintage Wodehouse. I was taking two cameras and I wanted to keep my money safe, so I bought a metal suitcase at some expense. It had a combination lock, and the salesman assured me it would take gelignite to open it if the lock was turned. It was heavy, so I took a light zip-fastened bag as well.

God knew where I would find myself from week to week, so I arranged with my bank to send money to certain places on my way where I could pick it up by producing my passport. I don’t like travelling with bundles of notes or even large numbers of traveller’s cheques. I bought a money belt, too, but in the end I used it only in the Sulu Sea, thinking that the pirates there might strip and search me without stopping to examine the back of an ordinary-looking belt. (The result of this subterfuge was that a number of banknotes were so damaged by salt water and sweat that for a long time in the Philippines I hesitated to try to pass them.)

It was going to be wet at sea and possibly cold, so I took my old green Grenfell anorak from Vietnam days. I had thick-soled, strong shoes and a pair of lighter ones to wear ashore. Medicines: I bought Septrin, Mexaform (for diarrhoea) and aspirin. I washed out my father’s hip flask and filled it with Scotch. A newly acquired Polaroid camera was to prove almost as useful to me in breaking the ice with shy and hostile strangers as beads were to explorers of old.

I couldn’t think of anything else.

At last I was ready for the traveller’s roulette to begin, and drove to London airport to catch the Athens flight.

*

There is no better place than a crowded European airport on an August morning in which to say a tearless farewell to air travel for a few months. With its look of a tarted-up transit camp, London airport stifles euphoria at the best of times. Even so, I felt none of the elation you might expect in an adventurer departing for Eastern seas among crowds of August holidaymakers morosely contemplating the big boards announcing delays in their flights to Vienna, Rome and Lisbon.

I had spent a late last night – reluctant, when it came to it, to abandon friends for a seagoing mystery tour almost half across the world on unscheduled ships. In thirty years of travel I have seldom begun a long journey without the feeling that I shall never return, and this beginning was no exception.

I edged my way to the bar and ordered a small black coffee. ‘Oh, and a Fernet Branca, please.’

‘Brave man,’ the barman said, and poured so generously that a small puddle of the dark-brown liquid formed around the base of the glass. I took his generosity as a good omen.

The Fernet Branca’s bitter warmth raised my spirits a notch or two. Soon a precise English female voice on the loudspeaker system announced that the Athens flight would leave on time, and this helped as well. But it was a false prophecy. Another two hours went by before we were allowed to board and listen to the captain apologizing for the delay, caused, he said, by air-traffic congestion. And another hour before the arrival of plastic trays bearing the airline’s ‘paprika sauce’ congealing on ‘turkey escalopes’ that retained the consistency of corrugated cardboard. The delays in the shipping world, I know now from experience, run into days or weeks, not hours, but only one out of the bizarre diversity of vessels I was to take on my long sea road to China produced food less appetizing than that airline meal between London and Athens.

I bought a cognac to wash away the taste and then the clear white Alps were below us. Later still, at last, the even clearer blue of Salamis Bay. Motorboats drew snowy trails among the islands and headlands basking in the warm sea. Seagulls wheeled and whitecaps flickered against the blue water – blue and white, the colours of the Greek flag. It was like a photograph on one of the postcards my fellow passengers would be sending home, whose recipients would sniff in disbelief at the unnaturalness of the colour reproduction. Here Europe ended; somewhere in the haze and glint of the eastern Mediterranean Sea, Europe and Asia came together. Beyond Athens airport the first of my ships waited for me; and, beyond that, Asia.

For the moment, Athens, much less Asia, was inaccessible beyond six long lines of passengers waiting for passport control. Evidently four jumbo jets had arrived at the same time.

A woman near me was saying, ‘It’s better at London airport, isn’t it? Better organized, really.’

I went through customs behind two florid young Englishmen dressed in identical brown blazers with brass buttons who bantered, Bertie Wooster-fashion, in strong Yorkshire accents.

‘To the yacht and straight into the sea, what?’

‘Yeah. Second one in pays for the champagne.’

‘Roger, old man.’

When I had reached the city centre and checked into a modest hotel on Mount Lyccabetos that someone had told me about, the receptionist told me I still had time to see Thomas Cook’s before they closed. I wanted to make sure I could get on the next ship heading through the Greek islands to Patmos. I had been told that the hotel had a ‘lovely view of the Acropolis’, and I suppose that if I’d been a giraffe I might have spent some time peering at it around the corner of the hotel. My room, though perfectly comfortable, was gloomy and on the ground floor and looked out onto a busy construction site. ‘It’s the month for the tourist groups,’ the receptionist explained. It occurred to me that perhaps all the passenger ships were going to be full too, so I hurried to Cook’s office in Constitution Square.

Cook’s was oddly hard to find but, after an interlude of dodging through crowds of blond tourists in shorts, I found it in a corner of the square on the second floor of a tall modern building. A friendly Greek lady there told me that the next ship to sail in the direction I wanted would be the steamer Alcheon, a Greek passenger vessel leaving Piraeus the next day at two o’clock in the afternoon for her regular run through the Aegean. She will stop, as usual, the lady said, at the island of Mikonos, and reach Patmos in the middle of the following night. Eleven hours; it seemed worthwhile to book a cabin.

The Cook’s lady blew her nose into a Kleenex, made a telephone call and reported, ‘Tomorrow there’s only one berth left. In a cabin with three other people.’

‘Any way of knowing who they are?’

‘No.’

It didn’t matter. It was a stroke of luck that there was any berth at all. ‘I’ll take it.’ At least it would be somewhere to lodge my ironclad suitcase. As I put my ticket and passport away, the Cook’s lady said, ‘I should board at one o’clock, if I were you.’

With my first steamship ticket in my pocket, there was time for a quiet evening in Athens. I had no intention of sightseeing; I had been to Athens several times before. I had pottered about the Parthenon and could remember enough nights filled with retsina, smashed plates and table-dancing to twanging bouzoukis, the Greek equivalent of the zither, in tavernas full of apaches. Enough of that – at least until Cyprus. For someone about to walk the plank from Europe into Eastern seas, only the peace of Orfanides’s beckoned with a wrinkled, ouzo-scented finger. But first I stopped at the bookstall of the Grande Bretagne Hotel and bought the Kümmerly and Frey map of Greece, the Geographia map of Turkey (which covers Syria, Cyprus and Lebanon too), some prickly-heat powder and half a dozen postcards. Then I strolled around the corner to old Orfanides’s.

I say ‘old’ Orfanides. For whoever Orfanides is and whatever his age – let’s hope he’s still alive – he cannot be young. His bar, too, has the right kind of old dusty shelves, the right number of old dusty bottles around its walls, a marble-topped wooden bar inside at one end, and small tables at the opposite end and outside on the street. ‘The Oldest Bar in Athens’ is Orfanides’s claim – ‘Established in 1916’. The fan on a wall over the bar is massive and rusty and is probably one of the first revolving fans ever made, but it works. It is needed because it is unlikely that one’s blood temperature will remain unaffected by the intake of alcohol made possible by the provision of a thick finger of ouzo for ten pence and a glass of Samos wine for twenty.

I took a table on the street and, when I had ordered ouzo, ice, a glass of water and a small plate of olives, I took my Alcheon ticket from my pocket and laid it carefully on the table next to the map of Greece. The rush of leaving England and friends, the many details I’d had to tidy up before leaving and the flight itself had all combined to smother any sense of what I was now embarked on. I wanted to brood on that first ticket. I wanted a reminder that I was going to China on slow boats, and that my destination was several months and thousands of miles away. I wanted to let the blissful thought seep into my head that, after nearly twenty years and fourteen wars, I was not embarking on one more harassing sprint for the Observer. In other words, I needed to slip into neutral, and Orfanides’s was a good place for that. Once it had been a comforting place in an ugly time.

In 1967, when I was Paris correspondent of the Observer, a trio of colonels seized power in Greece. I knew what to expect from London and it soon came: a telephone call from the Observer’s foreign news editor. ‘How about a trip to Athens?’ he said.

The next day I had found the lobby of the Grande Bretagne crowded and chaotic. My friends Jo Menell and John Morgan with their BBC television crew were struggling with cameras, recording apparatus and miles of cable halfway in and halfway out of the glass-front doors. We had last met in the horrendous pandemonium of Vietnam the year before. Full-scale repression in Greece and mass graves of Greek and Turkish civilians in Cyprus were still in the future when I came upon Jo and John. At the time, the situation seemed mildly laughable but, in the days that followed, laughter died away, and the grim routine of revolution closed around the Greeks. Telephones whirred and clicked in a sinister way; friends of friends vanished overnight.

That first evening, Jo, John and I went despondently to Orfanides’s. The bar was full of equally despondent Greeks. Jo rapped the table and said ironically, ‘Gavin, you’re about to see the revival by the military of Greek democracy in its finest and purest form. Except that they’ll probably institute the death penalty for everything from homosexuality to zither music. They’ll have Socrates spinning in his grave.’

John and Jo had taken their camera into Orfanides’s to see if the elderly Greek customers there were willing to discuss the colonels. They didn’t expect that they would be, but neither the waiters nor the old gentlemen held it against Jo and John that they tried to film them. In the next few days we went there often, and one evening from Orfanides’s terrace we watched soldiers, priests and men in double-breasted suits parading by to impress wavering Athenians and foreigners with their ‘revolution’ and its permanence.

Now, twelve years later, the colonels were in jail and in disgrace.

I ordered another ouzo, watched the ice turn it to milk, put my ticket away, and felt glad to be watching a different sort of parade: the promenade of August tourists. A decorous lot, by and large. The hippies seemed to have moved on. Perhaps I would catch up with them in Goa or Ceylon; perhaps they’d just grown up and settled down with mortgages and televised soap opera. Elderly English: men in panama hats, white-moustached; women in sensible, low-heeled shoes and head scarves. Americans in small, round straw hats. Schools of young German males in shorts so brief and tight you wondered where they found room to park their genitalia, and their pretty but big-bottomed girls; slip-slopping their sandalled feet, they went past Orfanides’s to the grander Snack Bar, where a notice said in demotic German, ein deutsch sprechen.

When darkness fell, I ate something in a small restaurant and then found a taxi. It was quite late enough. After all, I was leaving for China next day.