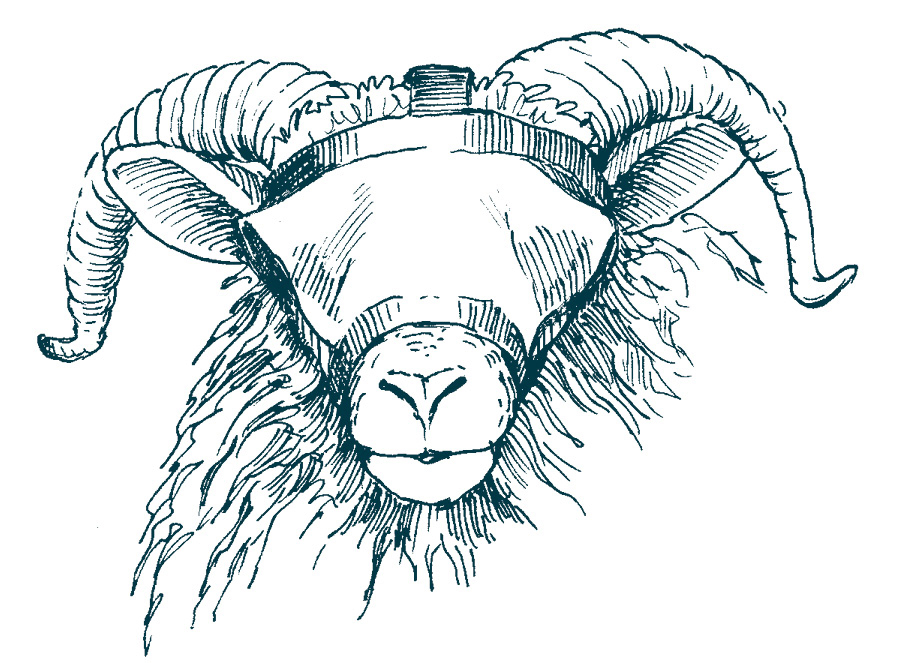

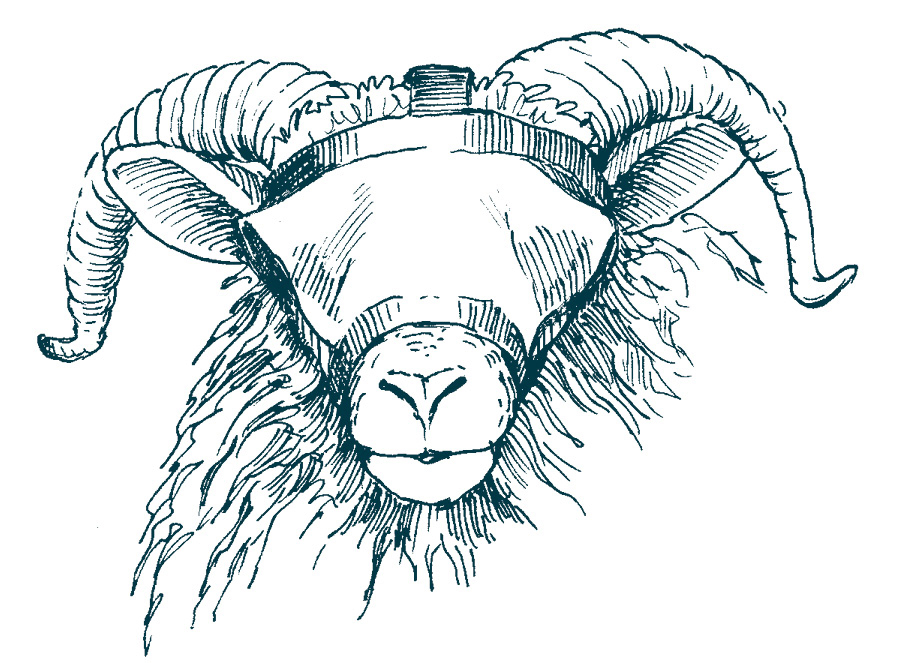

A ram shield prevents a rutting ram from charging and butting.

Little Lamb, who made thee?

Dost thou know who made thee?

— William Blake, “The Lamb” (1789)

Many shepherds say, “Don’t own a ram unless you need one.” If lambs are in your future, you do need one. Otherwise, you’ll have to borrow a ram or take your ewes to a ram to be bred. In most instances it’s better to keep your own ram for breeding.

I like rams. We have six of our own plus two long-term boarders. They aren’t terribly destructive and none are aggressive toward humans. Still, we carry our shepherd’s crook and keep an eye on the boys when we enter their paddock. Even docile rams sometimes react out of character. They’re sweet, but we never take them for granted.

If you have more than two or three ewes, and there are no compelling reasons to avoid keeping a ram (for example, lack of facilities or the presence of small children or vulnerable adults in your household who might wander into the ram’s pen and get hurt), it’s much less bother to own your own ram than to arrange for the use of someone else’s.

If he’s yours, you’ll know he’s healthy and that he won’t bring hoof rot or other diseases to your flock like a loaner ram might do. You’ll also be assured that your ewes won’t pick up any diseases as they might if they were to go elsewhere to visit a ram.

Buy (or, if need be, use or rent) a quality ram who complements your ewes. Every breeding ram should exemplify the qualities you’re breeding for, be it type, wool, size, meatiness, or any other characteristic. He should be healthy, free of specific breed faults (such as split eyelids in Jacob sheep or horns that spiral too close to the face in heavily horned breeds such as Icelandics and Scottish Blackface), and have two large testicles. Size of the testicles equates with fertility in rams. A truly bad-tempered ram is never a bargain; it’s not much fun interacting with your flock when you have to constantly watch your back.

Use these guidelines to plot your breeding strategies, keeping in mind that sheep sometimes don’t read the book. Precocious 3-month-old ram lambs have, for instance, impregnated their sisters and their dams.

Age at puberty: 5 to 10 months (single ewe lambs cycle younger than do lambs from multiple births)

Earliest breeding of spring ewe lambs: when they reach 60 to 75 percent of their expected adult weight

Heat cycle: every 13 to 19 days

Heat duration: 24 to 48 hours

Ovulation occurs: 20 to 30 hours after onset of estrus

Embryonic implantation occurs: 21 to 30 days after fertilization

Length of gestation: average 147 days, normal range 138 to 159 days (averages vary slightly by breed; primitive and early-maturing breeds generally have shorter gestations)

Number of young: 1 to 7 (singles or twins are the norm for most breeds)

Length of breeding season for seasonal breeds: August through February

Length of breeding season for aseasonal breeds: year-round but strongest August through February

Age at puberty: average 5 to 7 months or 50 to 60 percent of mature weight (some breeds reach puberty much younger than this)

Primary rut occurs: August to January (though most rams will breed ewes year-round)

Breeding ratio: 1 adult ram to 35 to 50 ewes; 1 ram lamb to 15 to 30 ewes

Eight percent of domestic rams prefer rams or wethers instead of ewes as sexual partners, according to research from the Oregon Health and Science University School of Medicine. Scientists don’t believe this behavior is related to dominance or flock hierarchy; instead, it seems to be associated with a region in the rams’ brains that is half the size of the corresponding region in heterosexual rams. To avoid problems, it’s best to buy a proven ram. Or, if you choose a ram lamb for your future sire, ask for a written breeding guarantee.

Be careful if you take your ewes to another person’s ram. Be certain the destination farm is free of hoof rot and CL and that your ewes will be housed separately from the farm’s other sheep. If you’re taking a single ewe, find out where she’ll be kept; she should have her own quarters but be able to see other sheep. Find out in advance what the breeding fee covers: Breeding through a single heat cycle? Return breedings until she becomes pregnant? Will you be charged extra for board? Can you bring your ewes’ accustomed feed if you want to? Work out the details (and put them in writing) before you commit.

If you rent or borrow a ram, establish who is responsible for veterinary bills if he becomes injured as well as what happens if he dies in your possession. Allow enough time before breeding season begins to quarantine him for 30 days, even if you’re sure he comes from a disease-free flock.

Most wool sheep are seasonal breeders, which means they’re most likely to breed in the fall, when days are growing shorter and temperatures cooler. Ewes become receptive and rams go into rut. This is when you must take special care around your ram; even gentle rams get edgy this time of year.

The verb “to ram” is derived from the Old English word ramm, meaning an intact male sheep. And ramming is what rutting rams do. They back off a distance, lower their heads, then race forward and smack their opponent, poll first. Crash! Some rams show aggression toward humans by backing, running, then jumping and slamming to a halt just before connecting with their human target. Don’t allow it!

If your ram is only occasionally feisty, be ready with a bucketful of water to dash in his face. Or, if you’re quick, strong, and fearless, grab him mid-charge and roll him over, then hold him down for at least five minutes.

Most butting behavior toward humans can be avoided by never fooling with a ram’s face or forehead, beginning when he’s a tiny lamb. Never play pushing games with a ram lamb; it’s cute, but he’ll grow up thinking you’re his opponent. It’s not as amusing when he’s grown and takes you by surprise.

If cornered by an ornery ram, look big. Stand tall and hold your arms out to the sides. Extend your outward reach using sticks, a shepherd’s crook, or anything else at hand. Don’t turn your back. The ram should back down first. If he charges, rap him smartly on the fleshy part of his nose with your stick. Aim well. Don’t injure his eyes or smack his forehead, horns, or poll. If you do, he’ll think you’re extending a challenge.

To reward your ram, scratch his chin. He’ll love it and it encourages him to raise his chin, which in turn defuses his inborn instinct to lower his head and charge. You can also scratch his back or his chest, but only if he’s gentle and not in rut. Leave his head alone!

And if he’s a good ram most of the time, fit your seasonally testy ram with a ram shield. This is a sturdy leather mask that allows him to see to both sides but not home in on a frontal target. Sheep, however, sometimes gang up on an individual wearing a ram shield, so remove aggressive flock mates if they won’t leave him alone.

A ram shield prevents a rutting ram from charging and butting.

A good way to keep track of a potentially ornery ram is to hang a bell on a collar around his neck. Then you can tell where he is at all times. It’s best, however, to use a bell collar that will break if he snags it on something really solid; you don’t want him to hang himself or break his neck.

In 2002 we moved from our woodland acres in east central Minnesota to a ridgetop farm in the southern Ozarks. One of the first things we learned was that our neighbor across the road raised cattle, lots of cattle. In addition to his own property, he rented six hundred acres of pasture from another neighbor down the road whose acreage abuts ours in back. He and the two cowboys who worked for him frequently rode down the dirt-track township road that fronts our farm, either on horseback or driving a battered farm truck.

A few weeks after our arrival, I spied a large spider sunning itself on the paved county road. A (mostly) recovered arachnophobe, I was determined to see it close at hand, so I pulled to the roadside and sidled up to the creature. As I stood there clenching my teeth, clutching my fists to my chest, and wondering if I dared get any closer, the neighbor’s battered pickup came barreling down the road. It screeched to a stop, and the cowboy on the passenger’s side asked me, “You got trouble?”

“No,” I told him, “but thank you. I was just wondering what this is.” (Meaning, “Is this an Arkansas Chocolate Tarantula?”)

The two cowboys exchanged a knowing look. (“Really ignorant northern woman,” was what it said.)

“It’s a spaahder [spider],” he told me.

After that I became a continuing source of amusement for them, or so it seemed to me. Whenever I did something stupid, they were there. Like the time I chased our errant, runaway beagle down the driveway and out into the road, wearing my jammies, just as the battered pickup crested the hill. Or the hot summer’s day I was kicking back, eyes closed, luxuriously cooling off in the llamas’ wading pool, and they came trotting up our driveway on horseback to borrow a dose of Banamine.

In December 2003 I bought my first registered Miniature Cheviot sheep, Baasha, and a ram lamb named Abram. Abram was ultra-friendly, and he quickly became a pet. A bad idea, I knew, but he was so darned cute.

(Background: I learned about woollies by helping a friend with her small flock of spotted Jacob sheep and her very ornery ram. It wasn’t his fault; as a lamb his owners played with him by pushing on his forehead so that he’d push back.

When he grew up and began ramming people in earnest, the family returned him to his breeder, who sold him to my friend. After I was knocked down and thoroughly worked over by this ram, my friend showed me how to subdue him by grabbing a front leg, moving quickly to his side, and flopping him down on the ground.)

So, back to Abram: As I walked among the sheep (in the pasture bordering the township road, of course), he would flip into ram mode and begin backing up to charge. Then he’d race toward me, hopping to a stop just before making contact. I didn’t like that, so I took my friend’s approach and tried to flip him to the ground. Miniature Cheviots, however, have long, broad bodies set on short, wide-set legs, so I couldn’t quickly roll him over as I’d learned.

Instead I grabbed both front legs; by lifting his fore end and throwing my body against his shoulder, I could lay him down. Exactly twice I could do this. Then he discovered that if he hopped on his hind legs, I couldn’t get beside him to shoulder him down.

One morning after Abram discovered the hopping trick, we were waltzing across the field when a familiar battered truck crested the hill. It slammed to a halt, and its grinning occupants watched us with open delight. I later learned (through a mutual acquaintance who was there) that they were on their way to a café in Hardy, where they entertained the coffee-drinkers’ table with loud guffaws and a vivid description of the crazy lady up the ridge who dances with sheep.

Not long after that our neighbor downsized his cattle operation and the cowboys stopped driving by. I still do stupid things, but in a perverse way, I sort of miss my audience.

The two basic modes of breeding are pasture breeding (the ram lives in the flock with the ewes) and pen breeding (both parties are taken to a pen where the mating occurs). Since we have multiple rams, we prefer pen breeding. Since our breeding pen is situated where we can keep an eye on what’s going on, we know the exact date when each ewe is bred.

Ewes in heat seek out and stay near the ram. Some sniff, lick, or nuzzle him as well. A ram approaching a potential girlfriend sniffs her urine, nudges her, grunts, pants, and flehmens. If the ewe is in heat, she’ll stand for his advances; she may also wag her tail. If disinterested, she’ll simply walk away.

Mating is achieved very quickly. Unless you’re observant you probably won’t see it occur, especially in a ram-in-the-pasture breeding situation.

Embryos aren’t implanted in a ewe’s uterus until 21 to 30 days after she becomes pregnant, so during that time avoid shearing, hoof trimming, showing, shipping, or anything else that might upset recently bred ewes.

Check vaccine and dewormer labels and if they shouldn’t be administered to pregnant ewes, use a wide-nib felt-tip marker to prominently note the fact on each bottle. I once absentmindedly dewormed my flock with Valbazen, even though I knew it shouldn’t be given to ewes within 45 days of conception (some shepherds, myself included, recommend avoiding it throughout pregnancy), and all of my lovely ewes aborted their lambs. Learn from my mistake: marking bottles with eye-catching warnings sometimes saves a world of heartache later on.

Feeding pregnant ewes is an art. Early and mid-gestation are critical periods because placental development occurs between 30 and 90 days after conception, while 70 percent of fetal development takes place during the last 4 to 6 weeks of gestation. But pouring on the feed isn’t the answer; overweight ewes are prone to pregnancy toxemia (see chapter 7), vaginal prolapses, and dystocia (lambing problems). What and how much to feed depends on many factors including your ewe’s age and breed, her body condition, how long she’s been pregnant, how many fetuses she’s carrying, when her lambs will be born, and types of available feed.

Early- and mid-gestation ewes should be fed a quality maintenance diet (see chapter 6). They shouldn’t be thin, but don’t let them become obese. They don’t require concentrates, but they do need good pasture or hay and access to sheep-specific minerals formulated for farms in your area.

Late-gestation ewes require additional energy, protein, calcium, selenium, and vitamin E. Energy equates with concentrates (grain). Adjusting for her pre-pregnancy size, the real or estimated number of lambs she’s carrying, and the quality and quantity of pasture or hay available, begin adding a small amount of grain to your ewe’s diet about six weeks prior to her due date, working up to 1 pound (450 g) per day just prior to lambing. According to the Merck Veterinary Manual, it also helps to include niacin in late-gestation ewes’ diet at the rate of 1 gram per day.

An exception to the rule is for ewes that you know, or strongly suspect, are carrying three or more lambs. As their fetuses mature, these ewes run out of room to properly digest hay, so you’ll want to limit their roughage intake. Instead, feed small amounts of high-quality hay, such as prime alfalfa, adding 1 pound (450 g) of grain per day per fetus, split into at least two feedings per day.

And because they’re still growing themselves, late-gestation spring ewe lambs require more energy by way of concentrates. Work them up to 1 pound (450 g) of grain twice a day.

Ewes’ requirements for calcium more than double during late gestation. Grains are notoriously low in calcium, though some high-quality forages, especially legumes such as alfalfa and clover, can supply most ewes’ needs. Supplying additional calcium through commercial grain mixes formulated for pregnant ewes (these also supply additional protein) or through high-calcium mineral supplements is a better approach.

Additional selenium and vitamin E are also needed during late gestation. Low selenium levels are implicated in retained placentas in ewes and white muscle disease in lambs. It’s important to know if your pastures or the land on which your feed is grown is selenium deficient. If it is, feed loose minerals that are high in selenium and vitamin E year-round or give late-gestation injections of a prescription substance called Bo-Se. Because we live in a very selenium-deficient zone, we give our pregnant ewes and does a Bo-Se shot about five weeks prior to lambing or kidding, at the rate of 1 cc per 40 pounds (18 kg) of body weight. However, too much selenium is toxic, so it’s very important to discuss its use and dosage with your County Extension service or veterinarian.

Oldest sheep: Lucky, a 23-year-old Polwarth-Dorchester ewe from Victoria, Australia (died 2009)

Heaviest newborn lamb: 38 pounds, United States (born 1975); 28 pounds, United Kingdom (born 1990)

Largest sheep: Stratford Whisper 23H, a Suffolk ram from Oregon, who weighed 545 pounds and stood 43 inches tall at the shoulder

World’s largest statue of a sheep: The Big Merino (nicknamed Rambo) measures 49 feet (15 meters) tall, 59 feet (18 meters) long, and 13 feet (4 meters) wide and towers over the freeway in Goulburn, New South Wales, Australia. Opened to the public on September 20, 1985, he houses a gift shop and a wool exhibit.

The trick to feeding late-gestation ewes is knowing how many lambs they’re carrying. The problem is, how do you know?

Ask if any local veterinarians offer pregnancy testing by means of ultrasound. An adept technician can ultrasound sheep between 25 and 90 days of pregnancy and tell you how many lambs each ewe conceived. Easy!

Otherwise, assume that exceptionally bulky-looking late-gestation ewes, especially of breeds known for multiples, are carrying more than one lamb; it’s usually better to judiciously feed for multiples and have a single lamb than the other way around.

Your late-gestation ewe needs plenty of stress-free exercise. A good way to help her move around more is to place feeders, water containers, and mineral tubs or dispensers in separate areas of pastures and paddocks so she has to walk back and forth between them. Give her a CD/T toxoid booster between five and seven weeks prior to lambing. She will then pass immunity to her lamb through her antibody-rich colostrum (first milk). If you live in a selenium-deficient area, this is the time for her Bo-Se shot as well.

Although it’s wise to forgo stressful situations as your ewe’s due date approaches, shearing prior to lambing is a good idea. With her fleece gone you can easily monitor her udder development, and her lambs will have an easier time finding her teats. There are two more good reasons to shear just before lambing.

Stress, and lambing is very stressful, usually causes a wool break (a weak spot) at skin level in a ewe’s fleece. If she’s shorn just before the break occurs, the break won’t devalue her fleece. Also, a fully fleeced ewe with new lambs is much more likely to take them out in the cold and wet than will a newly shorn ewe. Use common sense, though, and don’t shear winter-lambing ewes if the temperature is likely to fall astronomically low.

If shearing is out of the question, crutch your ewe about two weeks before lambing; crutching (sometimes called crotching) consists of trimming wool and dags (manure and urine-soaked locks of fleece) from around her udder and hind end. We use sharp Fiskars scissors for this job to reduce the sort of stress that electric shearing by amateurs can cause. And if you set her up on her butt, work quickly; a late-gestation ewe has trouble breathing in a tipped position. This is also the time to deworm her and to trim her feet.

Note: It’s especially important to monitor late-gestation ewes for pregnancy toxemia and hypocalcemia (milk fever), which are two common, potentially fatal metabolic diseases. See chapter 7 for a complete discussion.

I can’t imagine anything more exciting and rewarding than lambing time! Lambing isn’t, however, a stroll in the park. Proper nutrition and management can mean the difference between life and death for your ewe and her lambs. And if at all possible, you must be there when she lambs (you might want to use a baby or barn monitor at night). She might need help.

People say, “Sheep have been giving birth to lambs unassisted since time began.” That’s true, but a lot of ewes and lambs have needlessly died. In most instances, lambing goes off without a hitch, but when a ewe or lamb needs help, they need it badly.

Though ewes may lamb at any time of the day or night, peak lambing times occur between 9 am and noon, then again between 3 pm and 6 pm. Ewes often lamb at dawn or dusk as well.

Ewes like to pick their own place to lamb, but it should be in a clean, dry environment. To reduce stress (sheep don’t handle change well), move your ewe to the lambing area at least a week before her first due date. She needs company, so take along at least two other sheep, preferably her friends or daughters or her mom.

A grassy paddock with shelter is ideal in good weather; otherwise, a large, clean area indoors will do. It shouldn’t be small. A ewe moves around during first-stage labor; lying down, getting up, and lying down again helps position her lambs for a safe delivery. Don’t pen her in a stall; she needs room to maneuver.

When she picks a spot, don’t move her unless there is a compelling reason to do so. Lambing in a light, warm rain is perfectly okay; outside in torrential rain or a blizzard is not.

Once she enters second-stage labor, she should stay where she is until her final lamb is born. Don’t move her to a jug (a mothering pen) until she’s finished. Moving her to a jug mid-delivery disorients her, interrupts her labor, and gives her less room to lamb. And, in such tight quarters, she’s much more likely to lie down on a newborn lamb while giving birth to its siblings.

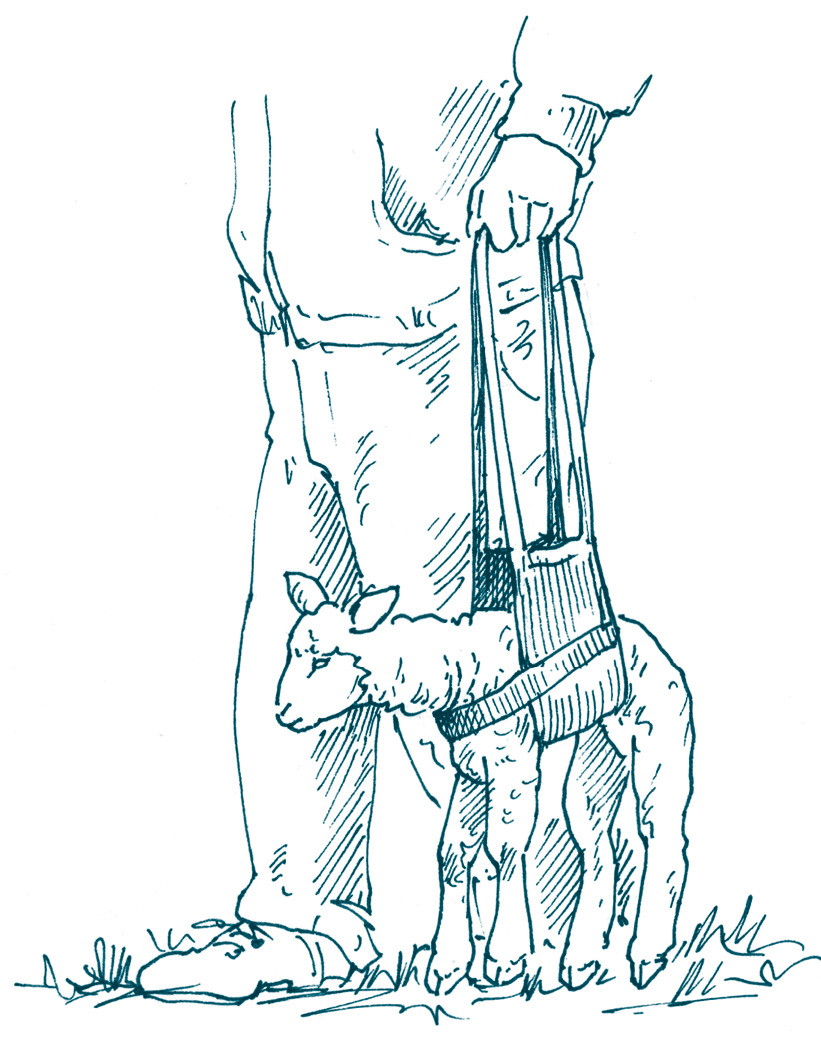

A note about moving her to a jug after lambing: if you pick up her lamb or lambs and use them to show the way, she’ll follow. Ewes are not, however, wired to look for flying lambs. You must bend over and carry them with their feet barely skimming the ground. This is a backbreaker and unwieldy if more than two lambs need to be moved. Save your back; buy a lamb sling. Also, keep in mind that if she loses sight of the lambs for an instant, she will race back, frantically baah-ing, to the spot where she gave birth to look for them. There always seem to be a few false starts, so expect them.

Using a lamb sling

Frank Kleinheinz’s advice (see page 125) is as good today as it was when he wrote it 100 years ago. It’s important to be there when ewes lamb, whether you have two ewes or two hundred.

Years ago when I helped foal mares for a horse breeder friend, I perfected the art of sleeping in a barn. It’s an adventure! First, find the perfect spot for your sleeping and observation area. You should be situated where you can see your ewe but not so close that your presence makes her nervous.

Choose a comfortable cot or make a comfy bed by stacking a row of hay or straw bales side by side and long enough to accommodate your frame. Don’t use blankets; they pick up debris and require rearrangement every time you get up. Instead, choose a sleeping bag you can easily slip into and that is rated for the depth of cold you’ll face during lambing time. Avoid bags with flannel lining; these pick up debris, too.

Lighting can be a low-watt bulb left burning from dusk to dawn or (my choice) a string or two of Christmas lights; they throw enough subdued light to keep tabs on ewes and lend a festive air. If you’re far from the house and have a safe place to put it, install a microwave for heating water (and snacks, should you get the munchies in the middle of the night).

Don’t play music unless your ewe is accustomed to it. Reading is good, but bring an extra flashlight so you don’t run down the batteries of the flashlight in your lambing kit. In dim overhead lighting, a flashlight can help you see more clearly exactly where you need extra light. Check the ewe often, being as unobtrusive as you can.

Most ewes lamb without assistance, but you should be ready to help if the need arises. As your ewe’s due date approaches, clip your nails short and smooth the edges; you won’t have time for a manicure if you have to assist.

Program appropriate numbers into your cell phone; be sure you can phone a vet or a shepherd friend or two at the touch of a button.

Assemble a lambing kit and the supplies you’ll need if you find yourself with an orphan to feed. Collect nipples, bottles, and tube-feeding apparatus (see Lambing Kit, page 127), and if you don’t have a lactating dairy ewe or milk goat to provide milk for unexpected bottle babies, buy a bag of quality milk replacer to have on hand.

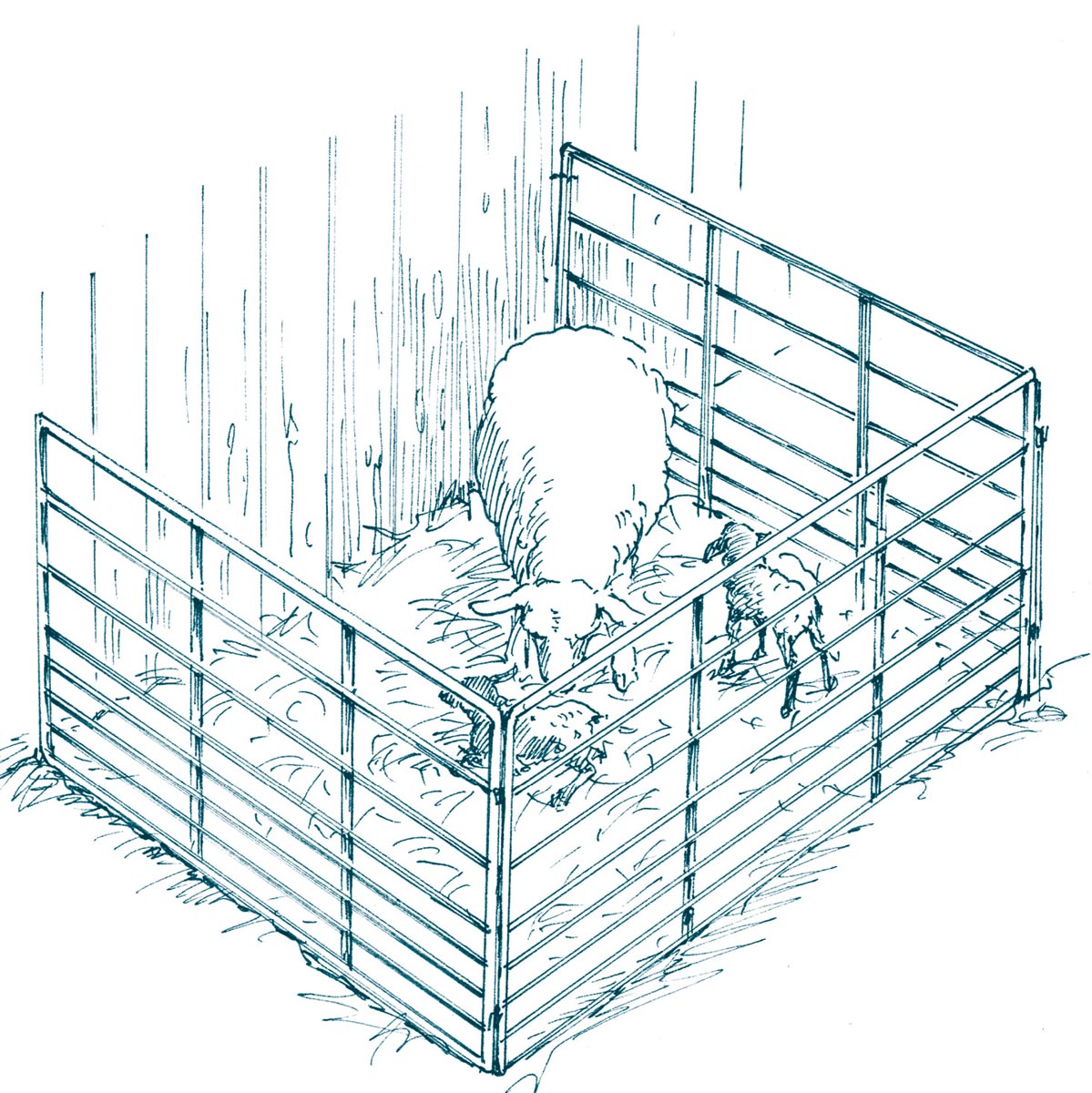

Ewes and their lambs should be placed in individual jugs for two to four days after lambing, so have one or more set up in advance. Jugs are small, safe pens where a ewe can bond with her lambs and recover in peace. Older, experienced ewes with single lambs might not need jugging but don’t count on it. It’s best to use a jug every time.

Set up jugs where drafts won’t be a problem. If that’s not possible, use jugs with solid sides. Otherwise, sheep panels set with their smallest openings near the ground and cut to size (4 x 4 feet [1.2 x 1.2 m] for ewes of small breeds such as Shetlands and Soay; 4 x 6 feet [1.2 x 1.8 m] or 5 x 5 feet [1.5 x 1.5 m] for bigger breeds) and secured with snaps or wire work very well.

Or improvise. We’ve used our two-horse trailer divided with safely stacked bales of straw when several ewes lambed at the same time and we needed one more jug.

A jug provides a calm, safe place for a ewe to bond with her new lamb.

On account of the dangers of lambing time it is most essential that the shepherd be near the flock at all times during this period. As a good shepherd must give up many hours of sleep in order to raise as large a percentage of lambs as possible, a small room should be provided for him in the sheep barn close to the lambing pens so that he may be comfortable during his weary watch. In this room should be a cot or bed upon which he can lie down when his duty does not require him to be with his flock. A stove should also be furnished so the shepherd may keep warm in cold weather. By keeping a teakettle of water on the stove he will always have warm water on hand, which is often needed. Otherwise, if he should find a chilled lamb which needs a warm bath at once to revive it, he will be compelled to run to the house, build a fire, and warm water, causing serious delay.

— Frank Kleinheinz, Sheep Management: A Handbook for the Shepherd and Student (1912)

Jugs shouldn’t be set up over cold, damp concrete floors, which even when bedded can chill newborn lambs. Bed with clean, non-musty straw or hay, not with wood chips or sawdust that can irritate lambs’ tender respiratory tracts.

Give water to jugged ewes in shallow containers. Never use deep buckets of water in a jug lest lambs fall in and drown.

A first-timer’s udder may begin enlarging as much as two or three weeks before lambing; a veteran ewe’s udder starts filling anywhere from ten days to a few hours before delivering her lambs. Most ewes develop strutted udders a day or so before lambing. A strutted udder is so engorged with colostrum that it’s firm and shiny and the teats jut out somewhat.

A ewe’s perineum (the hairless area around her vulva) usually bulges during the last few weeks of pregnancy. About 24 hours before lambing, the bulge subsides and the vulva becomes longer, puffier, and increasingly flaccid. The udders and vulvas of pink-skinned ewes flush a much deeper pink.

Release of the hormone relaxin causes structures in a ewe’s pelvis to soften as lambing approaches. As this occurs her rump becomes increasingly steeper; the area along her spine sinks and her tail head rises. If she isn’t shorn but she’s tame, begin running your hands over the ewe’s body every day starting a few weeks before she’s due; then you can feel, rather than see, these changes.

Store your lambing supplies in something easy to lug around. We used to keep ours in a Rubbermaid toolbox-stool. It was roomy, it had a lift-out tray for small items, it was easy to carry to the barn, and it was much more comfortable to sit on than an overturned five-gallon bucket. Then the handle broke off, so we replaced it with a Coleman cooler. It’s even roomier and nicer to sit on! A large fishing tackle box is another fine option, or a book bag or day pack to sling on your back. You will need:

A bottle of 7% iodine to use to dip newborns’ navels. This is now a prescription item, so unless your veterinarian carries it, you might have to substitute a product like Triodine-7 (a weaker iodine of tincture) or Nolvasan (chlorhexidine); ask your vet for recommendations.

Shot glass or plastic film container to hold navel-dipping fluid

Scissors for trimming extra-long umbilical cords prior to dipping; disinfect and store them in a sturdy resealable plastic bag

Dental floss to tie off a bleeding umbilical cord (rarely needed)

Digital rectal thermometer

Bulb syringe, which are the kind used to suck mucous out of human infants’ nostrils

Shoulder-length obstetrical gloves, if you like them (I assist bare-handed)

Plentiful supply of obstetrical lubricant; you can’t have too much. We use SuperLube from Premier1.

Antiseptic cleanser like Betadine Scrub for cleaning ewes’ vulvas and human arms prior to assisting

Sharp pocket knife, because you never know when you might need one

Hemostat (ditto)

Lamb-carrying sling

Halter or collar and lead

Reliable flashlight with extra batteries

Clean terrycloth towels or a large roll of heavy-duty paper towels

Two or three lamb coats

Lamb feeding equipment (see page 144—page 149)

A note on lambing snares: I've heard so many stories about people tearing ewes with the cable and plastic kind that I would never recommend using one. The rubber ones are absolutely useless. I have a length of plain, clean, soft rope with slip loops tied on both ends that I can use if necessary and then discard and replace it.

As a young woman I loved James Herriot’s books. Sometimes the stories almost made my hair stand on end as the good doctor labored to deliver stuck lambs and calves. The thought, “I could never do that!” kept me from getting sheep for a very long time.

Eventually, I helped many foals be born, from my mares and from mares belonging to a breeder friend. She also had sheep, and after watching several uncomplicated lambings, I figured I could handle that, too.

Fate unknowingly smiled on me when I bought my first sheep.

My Classic/Miniature Cheviots are an old British hill breed selected for hardiness, easy lambing, and strong mothering instincts. But I do occasionally have to lend a helping hand, so as lambing approaches I make sure there’s plenty of lube in the lambing kit, and I remove my rings and file my fingernails short, just in case.

Late one afternoon, Wren, one of my favorite ewes, got that faraway look in her eye, an early sign of first-stage labor. Then she took herself to the far side of the pen and began pawing up dirt to make a nest. She’d stop, listen, turn around, and look at the ground (“Where are those lambs?”) and paw again. I brought my lambing kit, a book, and a can of soda out to the pen and settled in to wait.

By dusk she’d crept into the straw-bedded stall I planned to partition off for a mothering pen, but she was bothered by Nick, a wether I kept with her for company. Nick is kind of a big dumb boy, so he followed her around and kept getting in the way. I locked him out of the stall, and Wren got down to business.

I watched through the gate until the water bag appeared at her vulva. When she’d settled into her nest and stayed down and started straining, I quietly crept up behind her. Two front feet followed by a nose. Perfect! I encouraged (“Here comes lambie!”), Wren pushed, and out slid a perfect black lamb.

I squeegeed fluid from the lamb’s face with my fingers, and when Wren got up and the umbilical cord ruptured, I placed the lamb by her face. But first I took a peek. A ewe lamb! Yay! All of last year’s lambs were boys, so I’d put in an “order” for ewe lambs.

Wren crooned to her lamb and licked her. And licked and licked and licked. A short while later Wren’s head shot up and she looked surprised. She stopped licking, slung herself down, and popped out another beautiful, black ewe lamb.

Although I’ve assisted à la Herriot several times, things usually go according to plan, and it isn’t as scary as I thought. I love lambing time!