Thy teeth are like a flock of sheep that are even shorn, which came up from the washing; whereof every one bear twins, and none is barren among them.

— Song of Solomon (4:2; King James version)

About 95 percent of lambs are born in the normal nose and front feet first diving position. Furthermore, a normal delivery usually takes about five hours from the start of cervical dilation to delivery of the first lamb: four hours for cervical dilation and one hour for expulsion of the lamb.

Ewe lambs giving birth for the first time, obese ewes, skinny ewes, old ewes, and flabby ewes who didn’t get enough exercise in late gestation are more prone to birthing problems than are young, physically fit ewes.

In multiple births, the same sequence of rupture of the water bag and birth of a lamb is repeated for each delivery. If a second water bag appears at a ewe’s vulva as she’s cleaning one lamb, another is on its way. A normal interval between deliveries ranges from 10 to 60 minutes.

Lambing can be divided into three phases: first stage, when the ewe’s cervix dilates; second stage, the birth of her lambs; and third stage, expulsion of the placenta.

During first-stage labor, mild to moderate uterine contractions may cause a ewe to stretch and raise her tail or to lie down briefly and hold her breath. The following behaviors may also indicate first-stage labor, which generally lasts 4 to 12 hours.

Second-stage labor begins when the cervix is fully open and a fluid-filled bubble appears at the ewe’s vulva. This is the chorion, one of two separate sacs that enclose a developing fetus within its mother’s womb (the other is the amnion). Either or both sacs might burst within your ewe or at the same time her lamb is born.

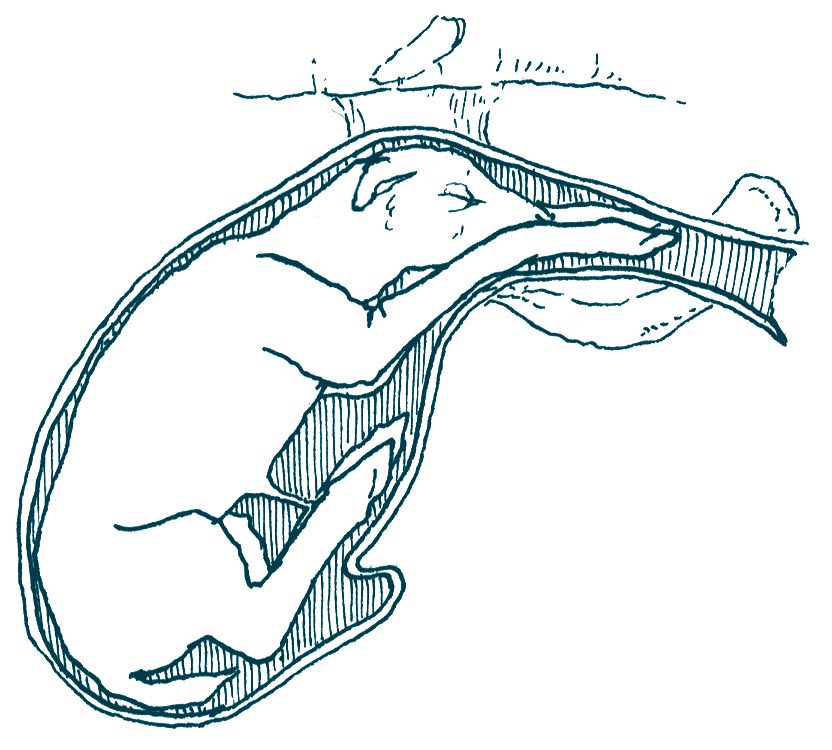

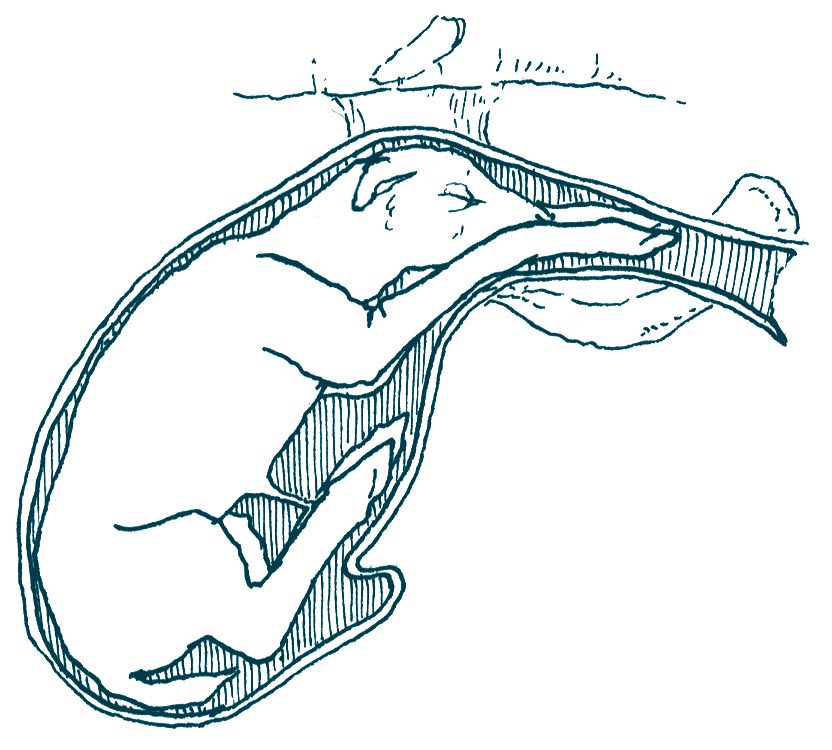

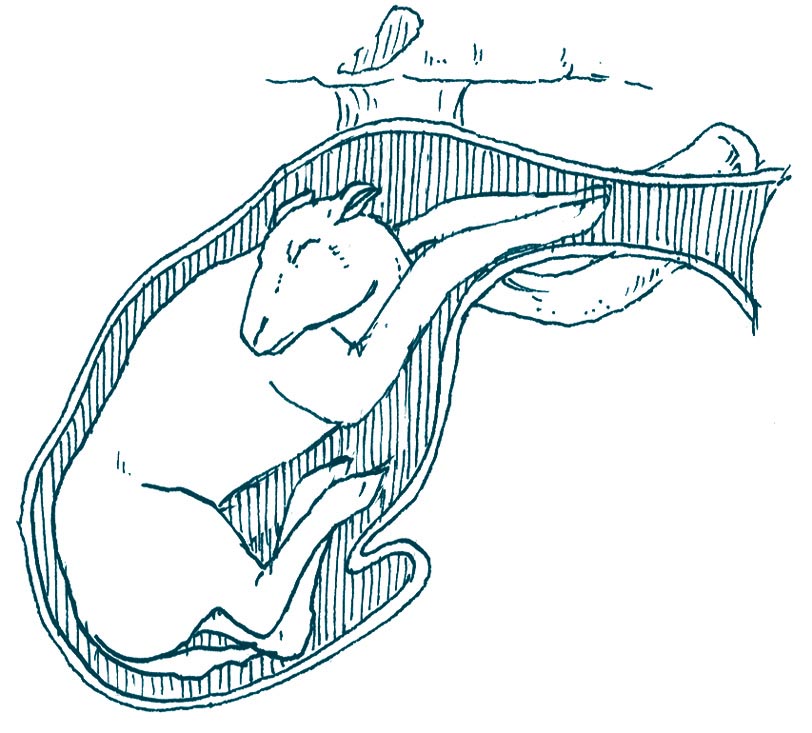

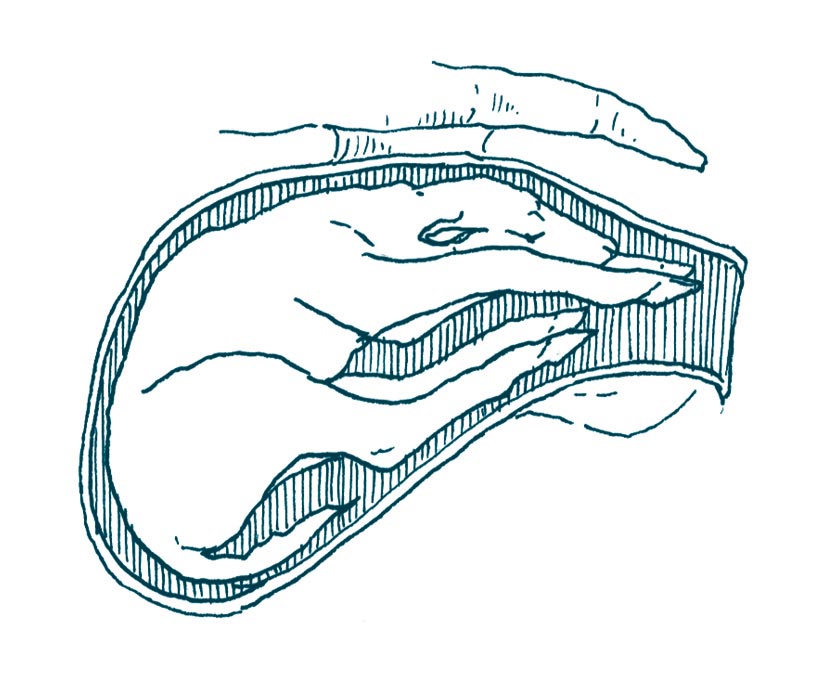

A normal diving-position delivery. In a normal front-feet-first, diving position delivery, the tip of a hoof appears inside the chorion (or directly in the vulva if the chorion has already burst), followed almost immediately by another hoof and then the lamb’s nose tucked close to his knees. Once the head and shoulders are delivered the rest of the lamb slips out.

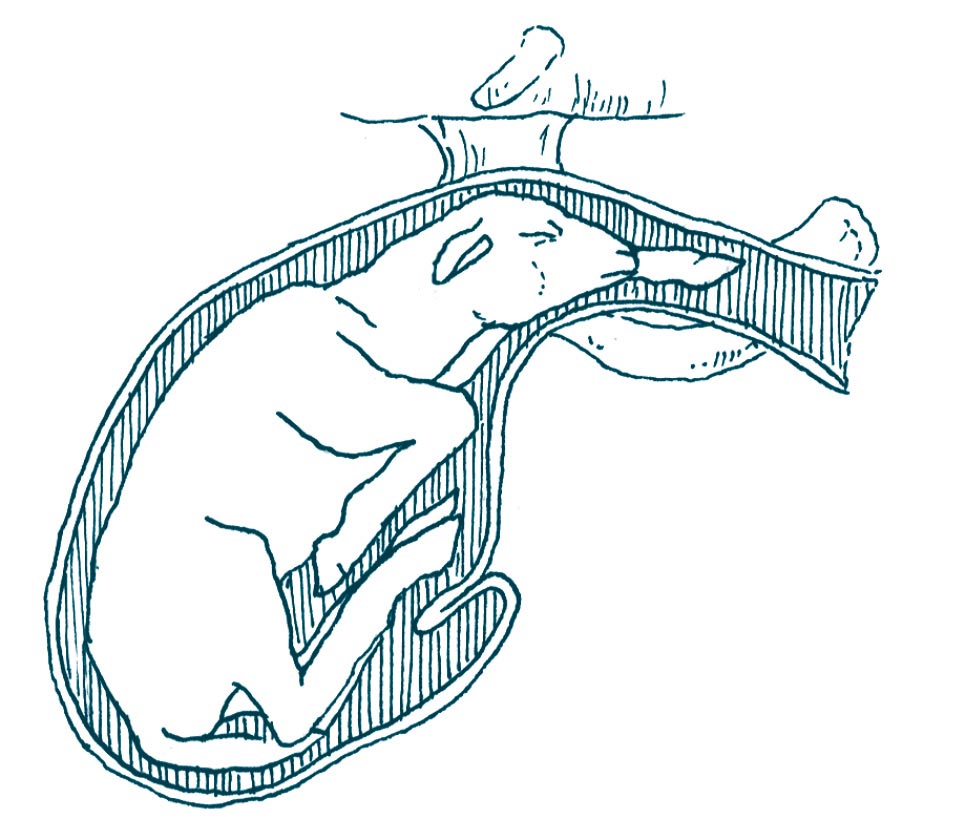

A normal hind-feet-first delivery. In a normal hind-feet-first delivery, two feet followed by hocks appear. The lamb’s umbilical cord is pressed against the rim of his mother’s pelvis during this delivery, so gently help the lamb out once his hips appear. Otherwise, these are both textbook deliveries and rarely require assistance.

Soon after the water bag appears, the ewe will lie down and roll onto her side as each contraction hits. She’ll ride out the contraction, then rise and repeatedly reposition herself until she finds a position she likes. Once she does, she may roll up onto her sternum with her forelegs tucked beneath her between contractions but she’ll usually remain lying down on her side, often with her head turned back toward one side. Some ewes deliver standing up or in a squatting position, and that’s okay, too.

Inexperienced shepherds tend to assist at lambing before help is actually needed. As long as a lamb is properly positioned and delivery is progressing, it’s best to leave things alone. Plan to assist if:

Sometimes, however, things go wrong and you should always be mentally prepared to assist. Sheep aren’t cows, and you can’t pull a lamb with tackle the way you’d pull a calf. If you do pull, slather lots of lube inside the birth canal alongside the lamb (you can’t use too much), and pull only while the ewe is pushing. Don’t pull straight back, pull down in a gentle arc toward your ewe’s hocks. To pull a lamb, grasp his legs, preferably above the pasterns but below the knees or hocks, and pull only during contractions. In an emergency you can also pull on his head.

Before examining your ewe internally, I can’t stress often enough that you must make sure your fingernails are as short and smoothed as possible and you’ve removed your watch and rings. Swab her vulva using warm water and mild soap or a product such as Betadine Scrub. Slip on a medical exam glove or scrub your hand and forearm with whatever you used to clean the ewe.

Then, liberally slather the glove or your hand and arm with lube and place lube inside her birth canal, too. Pinch your fingers together, making your hand as slim and elongated as possible, and gently ease your hand into her vulva, advancing only between contractions.

The inner lining of a ewe’s uterus is dotted with about 80 buttonlike projections called caruncles. These are where the placenta attaches to her uterus and are the reason you should never pull on the dangling parts of a retained placenta; it is still attached to the uterus and pulling can cause the organ to prolapse.

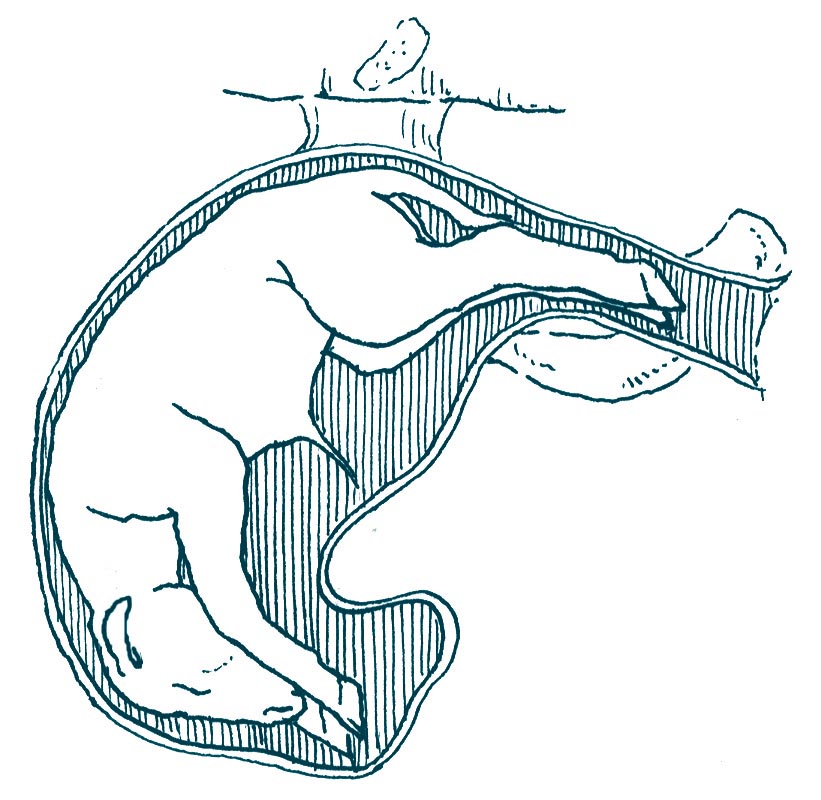

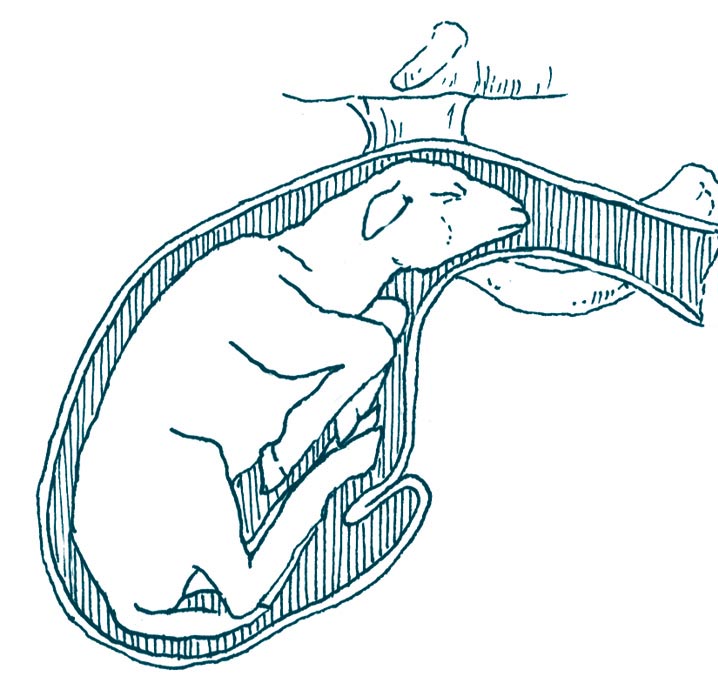

True Breech Presentation (butt first, hind Legs tucked forward). Some ewes can give birth in this position but most can’t. It’s difficult to reposition a true breech presentation, so call your vet. If you must reposition this lamb by yourself, try to elevate your ewe’s hindquarters before you begin.

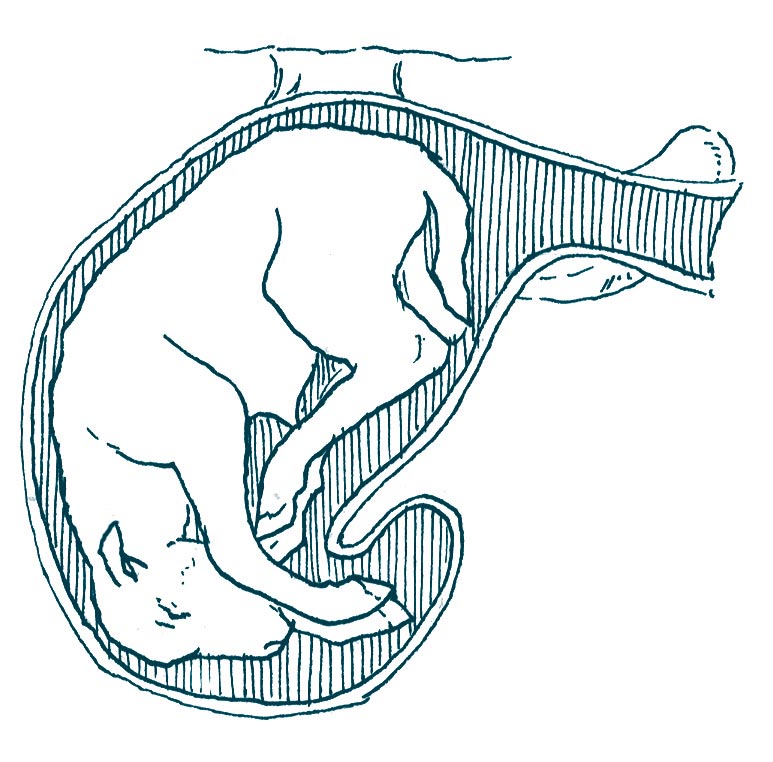

Head back. To correct this problem, attach a lamb snare to the front legs at the pasterns (or tie a length of cord to each pastern) so you don’t lose them, then push the lamb back as far as you can and bring his head around into position.

Sometimes the lamb’s front legs are presenting properly but his head is bent forward and down. This is more difficult to correct. If you have to reposition this yourself, do so in the same manner, but it’s a tough job, so enlist your veterinarian’s help if you can.

One leg back. Older ewes and large ewes delivering small lambs may deliver a lamb with one leg back. It’s best to reposition the trailing leg for first-timers and small ewes delivering large lambs. To do this, push the lamb back, hook your thumb and forefingers around his knee, and use the rest of your fingers to draw the leg forward into place.

Front legs back. Some ewes can deliver a normal-size lamb with one leg back, but if the ewe is young or the lamb is big, push the lamb back far enough to allow you to cup your hand around the trailing hoof and gently pull it forward.

It’s harder when both front legs are back and only the head is in the birth canal. Elevate the ewe’s hindquarters if you can, push the lamb back into her uterus, and bring the trailing legs forward one at a time.

Crosswise. This is definitely a job for your veterinarian. If he isn’t available, push the lamb as far back inside the ewe as you can (elevating her hindquarters will help) and determine which end is closest to the birth canal, then begin manipulating that end into position. These lambs are usually easier to deliver hind feet first.

All four legs at once. Attach a snare to one set of legs, making certain you have two front legs or two rear legs, not one of each, and then push the lamb back as far as you can. Reposition him for either a diving position or hind-feet-first delivery, depending on which set of legs you have in the snare.

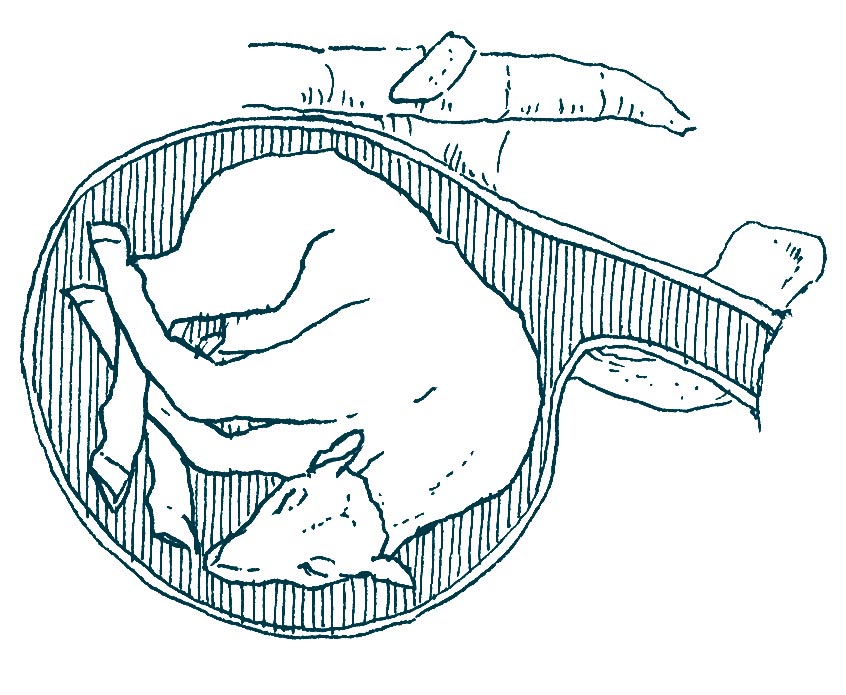

Twins coming out together. Attach a snare to the front legs of one lamb (follow the legs back to make sure they’re attached to the same lamb). Push the other lamb back as far as you can and bring the snared lamb into a normal birthing position.

If one lamb is reversed, follow the same protocol keeping in mind that it’s usually easier to pull the reversed lamb first. If both are reversed, pull the closest lamb first.

Figure out which parts of the lamb are present in the birth canal. If his toes point upward and the big joint above them bends away from the direction the toes are pointing, they’re forelegs. If his toes point down and the major joint bends in the same direction, they’re hind legs.

Follow each leg to the shoulder or groin to make sure the parts you’re feeling belong to the same lamb. If they do and if you can manipulate him into a normal birthing position, do so. Then, if the ewe is exhausted gently pull the lamb with each contraction; otherwise, sit back and allow the ewe to deliver the lamb herself. However, if you have to pull one lamb and others are waiting to be born, call your vet.

When repositioning a lamb, cup your hand over sharp extremities such as hooves and work carefully and deliberately. Any time you have to assist inside a ewe, you must follow the birth with a course of antibiotics. Ask your vet for advice.

This farmer has his hands full, as he juggles a baby while feeding two lambs. The back of the photo reads, “Matilda Pauline, 4 months old.”

Your ewe’s first lamb should be born within an hour after hard labor commences. Some producers swear by the 30-30-30 rule:

Some ewes, however, especially first-timers, take longer at each step.

You have two options if your ewe’s contractions stop before a properly positioned lamb already in the birth canal is born. The best is to call your veterinarian without delay. He’ll give her a shot of a drug called oxytocin to start her contractions again.

If the veterinarian can’t come, slather on plenty of lube and then go ahead and slowly pull the lamb. This is not easy and it’s very dangerous for your ewe. If you or the lamb tears her internally, she will die. Attempt this only as a last resort.

Disportionate size. Sometimes a lamb is too big or a ewe’s pelvic opening is too small for a lamb to be born in the normal manner. If you suspect this is the case and the lamb is alive, your veterinarian can deliver the lamb by C-section (caesarean); if the lamb is dead, he’ll dismember it and deliver it in sections, thus saving the ewe.

Sometimes a ewe’s cervix fails to fully dilate. While some shepherds attempt to gently work it open with their fingers, don’t. Call your veterinarian. If he can’t dilate the ewe’s cervix, he can deliver her lambs by C-section. Ringwomb should be left to the pros.

When the first lamb arrives, pull the chorion away from his face (tear it open if the lamb is still fully enclosed when he pops out) and strip birthing fluids from his nose by firmly squeegeeing your fingers along both sides of his face from just below his eyes down to his nose. If he’s struggling to breathe, use the bulb syringe from your lambing kit to remove excess fluid from his nostrils. If he’s really struggling to breathe or not breathing at all, take a secure grip on his hind legs between his hocks and pasterns (he will be very slippery, so hold on tight), place your hand behind his neck to support it as best you can, and swing him in a wide arc to clear fluid from his airways and jump-start his breathing.

A surprising number of lambs from assisted lambings appear to be dead; in fact their hearts are pumping, but they simply haven’t started to breathe. Swinging usually fixes that. Tickling the inside of his nostrils with a piece of straw or hay works, too. Don’t give up. If you keep stimulating these lambs, chances are they’ll start to breathe and be perfectly okay.

Often a lamb has a hard struggle at birth and arrives in this new world almost exhausted, lying without any signs of lung action. The shepherd has assisted the ewe in bringing the lamb forward, but it seems almost, but not quite dead. All that shows the lamb to be alive may be a single quiver. Now is the time he must act quickly to revive the lamb. The first thing is to clean all phlegm out of its mouth, then he must hold the mouth open with his two hands and blow gently three or four times into it to start up lung action. Now he must lay it on its belly and gently beat it slightly with his two hands, one on each side on its heart girth right back of the shoulder, and if it does not commence to breathe, he should blow into its mouth again. If there is the slightest bit of life left in the lamb, he will revive the lamb by this method. Many such lambs that at first sight appeared to be dead, have been revived by the writer in this method.

— Frank Kleinheinz, Sheep Management: A Handbook for the Shepherd and Student (1912)

Once he’s breathing, place the lamb in front of his mom so she can clean him. The taste and scent of her newborn creates a maternal bond. At some point she may leave him to deliver another lamb. This is normal. Simply place both lambs in front of her after the second one has arrived.

Once all lambs are born, think “snip, dip, strip, and sip.” Snip the umbilical cord to a manageable length if it’s overly long (about 11⁄2 inches [about 4 cm] is just right), dip the cord in iodine (fill a shot glass or film canister with iodine, hold the container to the lamb’s belly so the cord is completely submersed, then tip the lamb back to effect full coverage), strip your ewe’s teats to make certain they aren’t plugged and that she indeed has milk, then make sure all lambs sip their first meal of colostrum within an hour or so after they’re born.

The ewe’s placenta should pass within an hour or two after her final lamb arrives. Most ewes eat the afterbirth if you let them but this a choking hazard, so try to remove it before she gets to it. (I once had to give the sheep-y version of the Heimlich maneuver when a ewe tried to gobble her newly shed placenta and nearly died.) Wear gloves or pick it up with a plastic bag. Burn or bury it; don’t let your cats or dogs eat it. If the placenta hasn’t been delivered within 12 hours (you’ll know because bits will still be dangling from her vulva), call your veterinarian.

Every shepherd must be aware of two post-lambing infections: metritis and mastitis (see page 102). They don’t occur with every pregnancy but are serious conditions when they do occur, so be prepared.

A British friend suggests the following elixir for ewes stressed by a difficult delivery. She uses it all the time — and says it works for frazzled shepherds, too!

2 aspirins crushed and dissolved in 1⁄2 cup coffee

2 tablespoons honey

2 tablespoons whiskey

Stir well and dribble it into the ewe’s mouth using a small syringe with the needle removed.

Hope had been acting “off” for a few days, staring introspectively into space and occasionally taking herself away from the others as though she might lamb, so I watched her closely. On Mother’s Day morning she went into labor. I brought out my lambing kit and camera and settled in for another routine birth. It was not to be.

Hope got down to business, and her water bag burst. From that point there should have been front toes showing within 30 minutes. There weren’t. When I examined her internally, I found nothing but an enormous head, aligned sideways instead of vertically with Hope’s tail as it ought to be. I called John to come help and the ordeal began.

I pushed the lamb back into Hope’s uterus and began feeling for feet. There was only one. I worked it into position and kept searching. Nothing. It was desperately hot, Hope was screaming, and there was no second leg. Because she was a first-timer and tight, there was no way she could deliver the lamb with one leg back, nor could we pull it.

After an excruciating amount of time, John found the second leg and worked it into position, but there was too much lamb to fit through the birth canal. If we couldn’t pull the lamb, Hope would die. I promised Hope that if she survived this lambing, I would never, ever breed her again.

We hauled out another bottle of SuperLube, I held Hope, and John slowly, painfully, managed to pull the lamb, which flopped onto the straw, looking very, very big — and dead. I quickly stripped fluid from his nostrils and checked: he had a heartbeat but wasn’t breathing. We swung him, we shook him, and then we tried a primitive CPR technique I had learned from a century-old book (see Learn from the Past, page 135).

It worked! The lamb gasped, sneezed, and shook his head. We set him in front of his exhausted mom, and as if nothing was wrong, she began talking to the lamb and cleaning him.

We named the little guy Arthur, short for Wolf Moon Wee Mad Arthur (for a Nac Mac Feegle character in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books). He was strong once he began breathing and was up on his feet in record time.

There was blood, more blood than a normal birth, so I was very much afraid Hope would die. Yet she struggled to her feet in less than half an hour, and soon she was feeding baby Arthur. We treated her with penicillin and Banamine and held our breath. After 5 days I began breathing easier. Now I know what assistance “à la Herriot” is really like. And it was a Mother’s Day I (and Hope) will always remember.