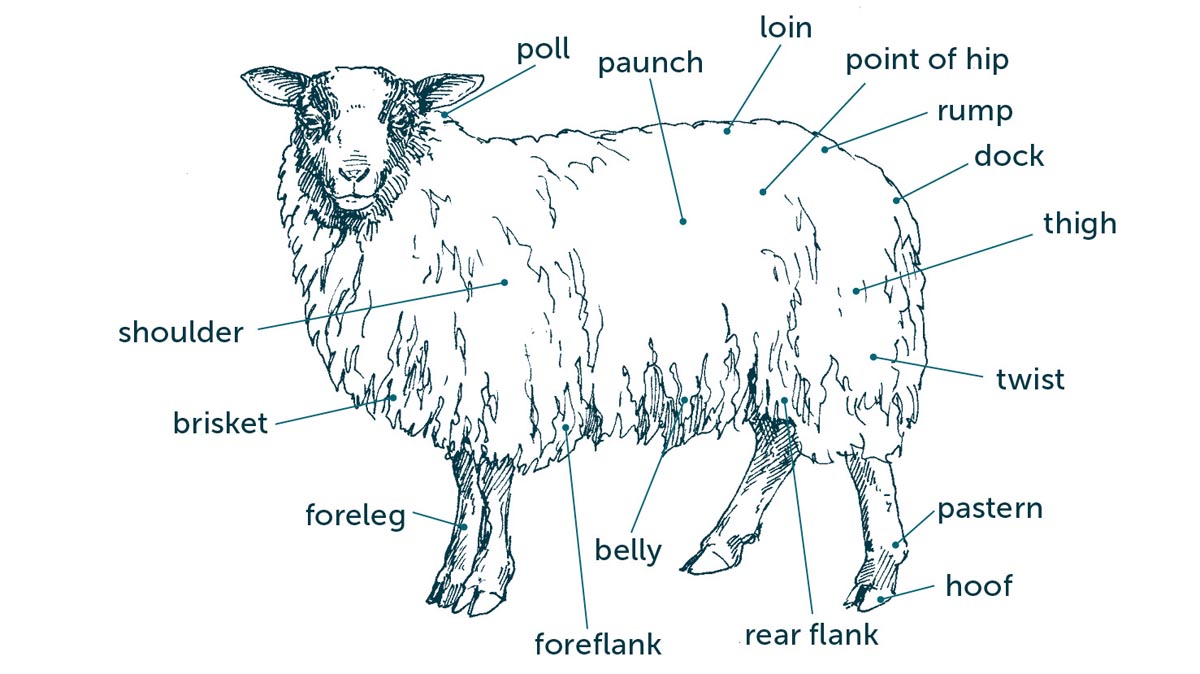

Parts of a Sheep

‘Now take a sheep’, the Sergeant said. ‘What is a sheep [but] millions of little bits of sheepness whirling around and doing intricate convolutions inside the sheep? What else is it but that?’

— Flann O'Brien, The Third Policeman (1967)

Sheep are reputed to be airheads, but in fact, they are reactive, not stupid. When you’re small, tasty, and defenseless, it’s best to run now and ask questions later. That doesn’t mean sheep aren’t smart. As Mark Twain put it, “It is just like man’s vanity and impertinence to call an animal dumb because it is dumb to his dull perceptions.”

British researchers, headed by neuroscientist Dr. Keith Kendrick at Cambridge University’s Babraham Institute, taught 20 sheep to recognize pictures of other sheep’s faces. They showed the sheep 25 pairs of similar faces, training them to associate recognition of the faces with a food reward. Two years later the team again showed the sheep the series of pictures, measuring their brain activity via electrodes implanted in their brains. Some remembered all 50 of the original faces, even in profile. “It’s a very sophisticated memory system,” explains Dr. Kendrick. “They are showing similar abilities in many ways to humans.” Pretty smart for a “dumb animal.”

Three years after their first experiment, Dr. Kendrick and his colleagues discovered that sheep prefer smiling or relaxed faces over those of angry humans or stressed-out sheep. They presented the test flock with two doors they could push open to grab a snack. One was covered by a picture of a smiling human or a contented sheep; the other, an angry human or a distressed sheep. They invariably chose the happy-face doors.

Caroline Lee, a member of the animal welfare team at the FD McMaster Laboratory in New South Wales, Australia, developed a test to measure intelligence and learning in sheep based on a complex, 59- by 26-foot (18 x 8 m) maze similar to those used for rats and mice. By penning part of the herd in sight at the exit, researchers used Merino sheep’s strong flocking instinct to motivate test sheep to go through the maze. The premise: the time it initially takes an animal to rejoin its flock indicates intelligence, while improvement in times over consecutive days of testing measures learning and memory. It took the 60 sheep an average of 2 minutes to go through the maze on day one and only 30 seconds on day three. When the sheep were retested six weeks later, they went through the maze even faster than they did on day three.

Finally, consider the smart sheep who live on a commons near Marsden, a village on the edge of the Pennine Hills in West Yorkshire, England. Because sheep had been continually raiding village gardens, authorities installed an 8-foot (2.4 m) cattle guard to keep the sheep out of town. Not to be thwarted, the sheep began lying down and rolling, commando-style, across the cattle grid. When BBC News asked a National Sheep Association spokeswoman about their behavior, she replied, “Sheep are quite intelligent creatures and have more brainpower than people are willing to give them credit for.”

Many an ignorant flockholder catches and takes hold of the sheep by the wool, at any place he can get hold of best. Men who do this do not realize that the skin of the sheep is very lightly attached to its flesh, and that by holding the sheep by the wool in this careless manner the skin is torn loose from the flesh as far and a little farther than the hand’s reach, thus injuring the innocent sheep. It has been our experience that it takes the sheep about two months to recover from the bruise thus caused.

— Frank Kleinheinz, Sheep Management: A Handbook for the Shepherd and Student (1912)

To understand why sheep do the things they do, try to imagine the world through a sheep’s five senses: vision, taste, hearing, smell, and touch.

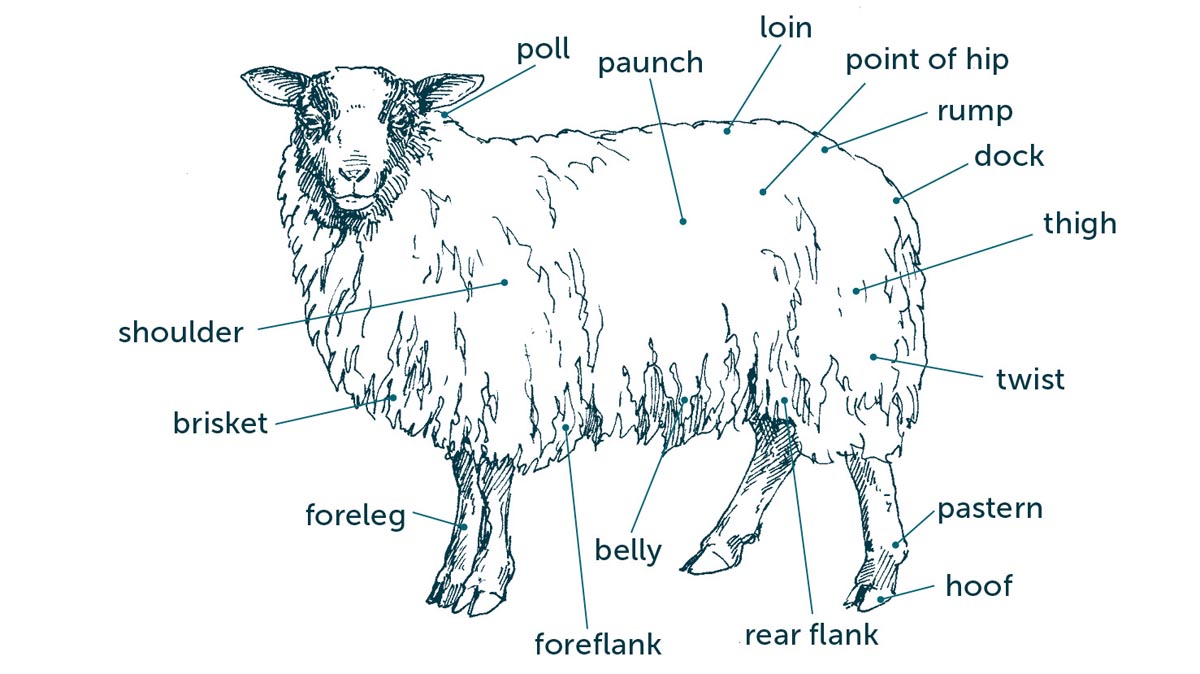

To the side, sheep have a wide monocular vision ranging from 270 to 340 degrees, depending on the shape of their faces and how much wool they have around their eyes that may obstruct their vision. Sheep have large, rectangular-shaped pupils, and their eyeballs are placed toward the sides of their heads, giving them a narrower field of binocular vision.

A sheep has a blind spot directly behind her, but by raising or lowering her head or by moving it from side to side, she can scan her entire surroundings. The rectangular pupils provide a wide-angle effect, giving sheep excellent peripheral vision. They can’t easily see objects high above their heads, however, and they have poor depth perception. Because of this, sheep avoid shadows and harsh contrasts of light and dark. They also tend to move away from darkness and toward light.

Based on research that determined the number of cones and rods in sheep’s eyes and on subsequent studies to understand how that number related to visual perception, scientists believe that sheep’s vision is very keen. They’ve also learned that sheep see in color, although their color acuity is lower than humans’.

Ewes lick their fluid-drenched newborn lambs and this creates a strong maternal bond. Rams sample urine from ewes in heat to determine if they’re ready to breed.

Sheep prefer certain feeds over others, indicating that they know what they like to eat. When grazing alongside other species such as goats and cattle, each species selects different types of plants.

Sheep hear well; they are sensitive to high-pitched and sudden noises, both of which trigger a surge of stress-related hormones. They refine their hearing by moving their ears, heads, or entire body to face whatever they’re focusing on.

Sheep have scant vocabularies as compared with, say, pigs or cows. Frantic, high-pitched baas are stress indicators. Adult sheep give medium-pitched baas when seeking older lambs, friends, or feed. Ewes murmur sweet “flutter baas” to their newborn lambs. Rams rumble when sexually aroused or annoyed at another sheep.

Sheep have a well-developed sense of smell. Ewes recognize their newborns by taste and scent. Rams sniff ewes to determine which ones are in heat. Sheep are capable of scenting water from afar and they sniff feed to determine if it’s safe to eat.

Both sexes also flehmen, whereby the sheep opens his mouth and curls back his upper lip to transfer scent to a structure called the Jacobson’s organ, or vomeronasal organ, located in the roof of his mouth. Rams frequently flehmen when sniffing the urine of a ewe in heat.

Once a sheep’s feet are off the ground and she can’t touch anything with her hooves, she remains still. That’s why shearers tip sheep to immobilize them for shearing. Tipping also works for routine tasks such as hoof trimming and doctoring minor wounds. Tipping a sheep seems daunting at first but is easy once you know how.

Standing on the left side of the sheep, reach across with your right hand and grasp her right rear flank by the skin (don’t pull her wool). With your left hand, bend her head away from you, back against her right shoulder. Lift the flank and pull the sheep toward you. This puts her off balance and theoretically she rolls gently toward you onto the ground. In practice, it doesn’t always happen that way. Persevere. Practice makes (almost) perfect.

Hold the sheep on her side, then quickly grasp both front legs and set her up on her rump so she’s slightly off center, resting on one hip. If she struggles, place one hand on her chest for support and inch backward until she’s more comfortable.

Don’t tip a sheep right after she has eaten, as the position puts considerable strain on a full rumen. For the same reason, don’t tip pregnant ewes for more than a few minutes at a time. Despite their good intentions, don’t let anyone try to help by holding the sheep’s legs; if her hooves encounter anything, even your helper’s hands, she will struggle to break free.

Sheep are less responsive to touch than other livestock species because they are covered with wool or thick, coarse hair. However, sheep have very sensitive skin under their wool. Please, don’t pull it!

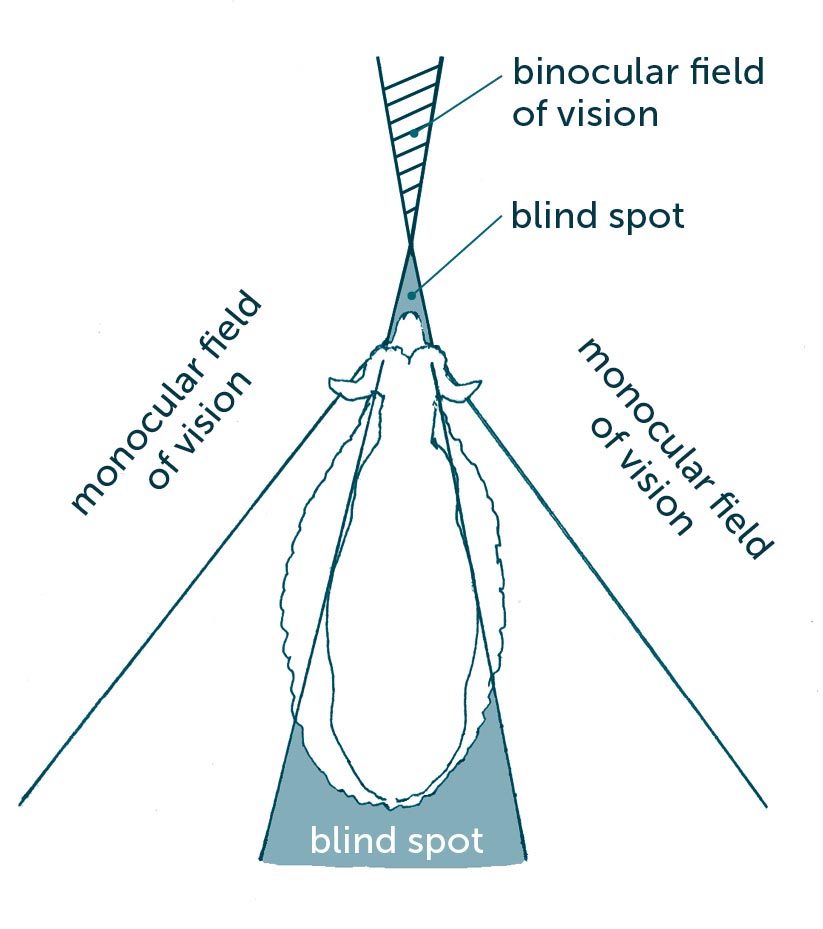

Estimating a sheep’s age by examining the eight teeth in the front of his mouth is easy. If all the teeth are sharp and small, they are baby teeth and the sheep is less than one year old. If the center two teeth are big (these are permanent teeth) and the rest are small, the sheep is between one and two years old. If the four center teeth are big and the rest are small, the sheep is about two years old. If the six center teeth are big and the rest are small, the sheep is about three years old. If all eight teeth are big, the sheep is about four years old. After that the teeth gradually spread and eventually fall out in old age.

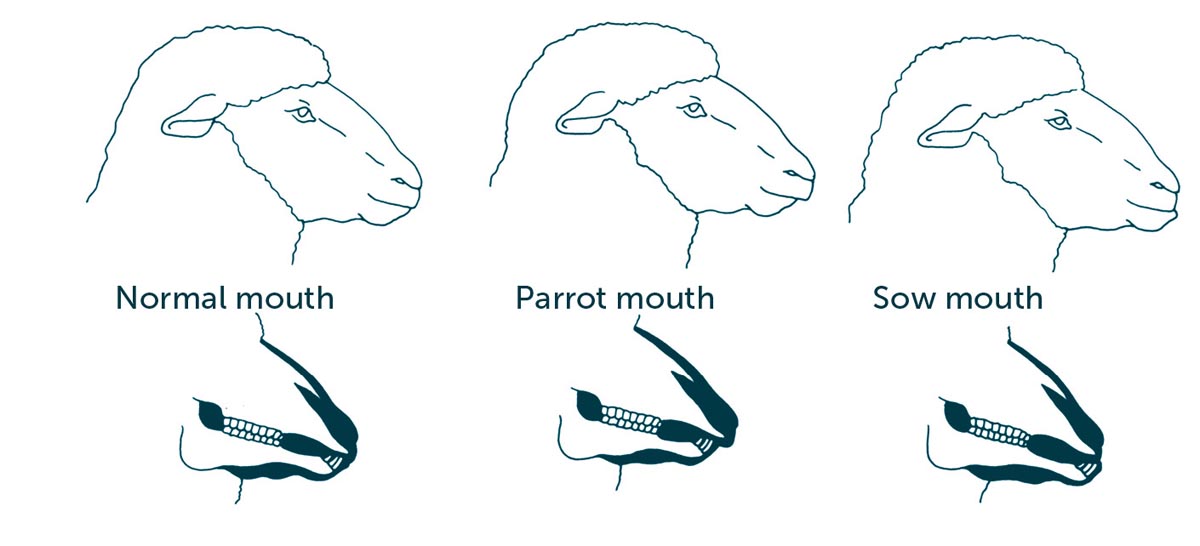

A sheep’s lower teeth should meet flush with the upper dental pad. If the lower teeth extend beyond the dental pad, she is “sow-mouthed” or “monkey-mouthed”; this is more common in Roman-nosed (arch-faced) breeds. If the dental pad extends beyond the lower teeth, she is “parrot-mouthed.”

Extremely parrot-mouthed or sow-mouthed sheep have problems grasping forage when browsing and grazing. They tend to lose weight on pasture and need hay and possibly grain to survive. Both conditions are hereditary and should be avoided; that is, don’t breed sheep who display these conformation flaws.

A well-defined pecking order exists within every flock whether composed of four or four hundred sheep. Where a sheep stands in this hierarchy depends on its age, sex, personality, aggressiveness toward other sheep, and the size of (or lack of) its horns. Suckling lambs assume their dam’s place in the order and often rank immediately below her after weaning.

Newcomers must fight to establish a place in the flock. Fighting for social position is conducted one on one; established flock members don’t gang up on a new one.

When fighting, rams back up and charge one another; both sexes butt, jostle, and push. Other forms of aggression include staring, horn threats (chin down, horns jutting forward), pressing horns or forehead against another sheep, backing up without actually charging another sheep, and ramming an opponent’s rear end or side. Very little infighting occurs in a static flock, however, once each member knows and accepts her place.

A major difference between sheep and goats is that sheep don’t follow a specific leader as goats do a herd queen. When one sheep starts moving, others follow, even in low-flocking breeds. High-ranking flock members move near the middle of the flock to avoid being in a vulnerable position should predators strike.

It takes a while for sheep to form a cohesive flock when individuals from different sources are mixed. Sheep form friendships and tend to stay in family groups of a ewe and her offspring, their offspring, and so on. In flocks made up of more than one breed, given enough space, sheep generally segregate themselves by breed.

The social group is very important to sheep and isolation is extremely stressful. An isolated sheep may go berserk, bleating loudly, running, and smashing into the sides of the pen. Even in quarantine or a sick bay, sheep should be able to see other sheep. (See chapters 8 and 9 to read about breeding and lambing behaviors.)

Two Birds and a Sheep Winery (Paso Robles, California)

Inherit the Sheep Winery (Napa, California)

Greedy Sheep Winery (Cowaramup, Western Australia)

Barking Sheep Wines (Mendoza Province, Argentina)

Ram’s Gate Winery (Sonoma, California)

Sheep’s Back Winery (South Melbourne, Victoria, Australia)

Black Sheep Winery (Murphys, California)

Ram’s Leap Wines (Warren, New South Wales, Australia)

Shepherd’s Run Winery (Wamboin, New South Wales, Australia)

Black Sheep Vineyard (Adena, Ohio)

Barking Sheep Chardonnay Chenin Blanc (Argentina)

Big Horn Buttface Amber Ale (USA)

Red Sheep Oak Aged Shiraz (Australia)

Golden Sheep Pale Ale (England)

Black Sheep Ale (England)

Sheep Head Ale (USA)

Inherit the Sheep Cabernet Sauvignon (USA)

Isaac’s Ram Wine (Israel)

Sheep Dip Whiskey (Scotland)

Black Ram Whiskey (Bulgaria)

Lambs begin playing within a few hours of birth. They stay close to their mothers for the first weeks of life, but as they get older, they venture farther and begin to form gangs. By the end of the first month they spend roughly 60 percent of their time with other lambs.

Play behaviors include mounting one another (both ram and ewe lambs do this), playful butting, racing to a set location and back again (“lambpedes”), jumping on and off of rocks or dirt piles en masse, Ninja-style kicking, leaping and whirling in place, and spronking (a Pepé le Pew gait in which lambs race while bouncing stiff-legged, all four feet hitting the ground at the same time). Ram lambs prefer manly games like play-fighting and mounting one another, while ewe lambs prefer to race. Play becomes infrequent after about nine months of age, although even adult sheep engage in play at times.

Pastured sheep prefer to camp (sleep and ruminate) on elevated ground, moving downhill to graze during the day. They generally graze in the early morning and again late in the afternoon, resting in their feeding area between grazing sessions. During periods of extreme heat and humidity they often rest from midmorning to evening and graze in late evening and at night. Sheep generally graze between five and ten hours a day, though grazing time is affected by many factors including weather, breed, quality and availability of pasture and supplemental feed such as tasty hay, and day length. Sheep prefer not to graze near sheep or goat droppings, but they aren’t offended by manure from other species.

Sheep have a remarkably dexterous and deeply cleft upper lip that permits very close grazing. As a sheep grazes, she jerks her head slightly forward and up to break grass and stems against the dental pad and lower front teeth. The cleft lip also allows her to sort feed; for example, she may consume all of her favorite bits of yummy corn from mixed grain and leave the oats and barley behind.

Sheep usually ruminate (chew their cud) while resting on their sternums (lying down with one or both front feet tucked under their bodies), but also sometimes while standing. The time spent ruminating is about equal to or slightly less than the time spent grazing. Rumination induces a state of drowsiness that sheep seem to enjoy.

All sheep flock to some degree, especially when frightened. Flocking instinct, however, varies greatly from breed to breed. Lambs are hardwired to follow their dams and then other members of the flock. Banding together in groups protects sheep from predators that home in on sheep grazing alone or on sheep at the edge of the flock. Flocking instinct is what enables shepherds to tend to and move large numbers of animals.

Fine-wool sheep like Merinos, Rambouillets, and Columbias flock closely while moving, grazing, or at rest; other breeds flock when moving but spread out somewhat to graze and rest. Leading low- and poorly flocking breeds with a bucket of feed is easier than trying to drive them.

Here are some additional points to consider:

Personal space. Sheep maintain personal security or flight zones. Anything scary invading a sheep’s personal space generates flight. A sheep’s flight zone might be 50 feet (15 m) or nothing at all. Breed, gender, tameness, training, and degree of perceived threat enter each equation.

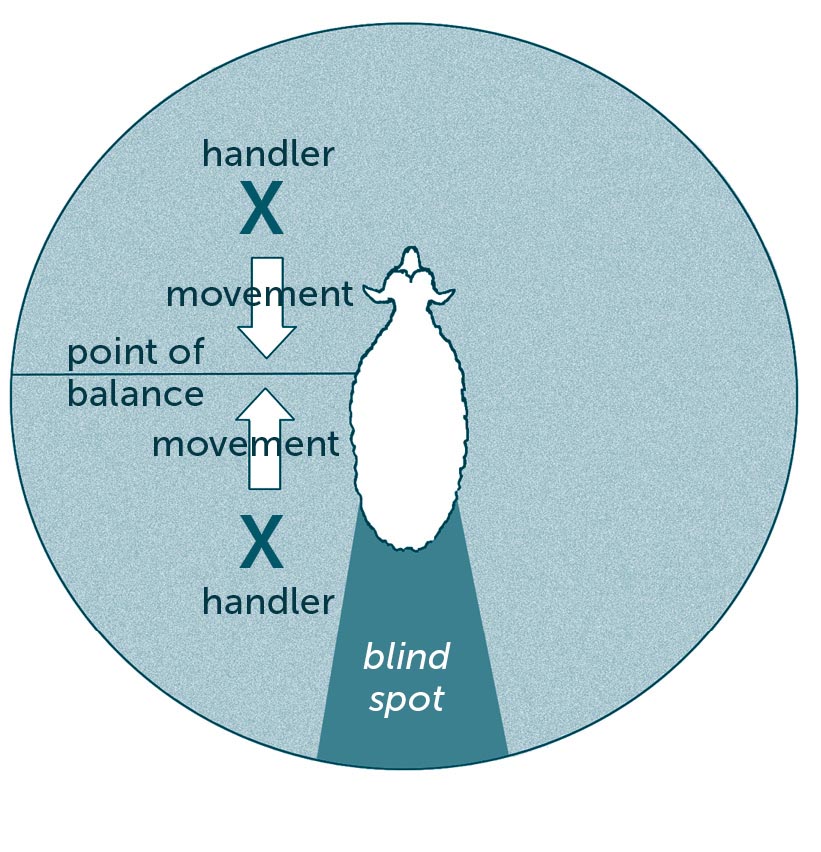

Point of balance. A sheep’s point of balance is at his shoulder, at a 90-degree angle from his spine. Movement within a sheep’s flight zone and behind his point of balance makes him move forward; movement in front of his point of balance and within his flight zone makes him turn and move away.

Herding sheep. When approaching or driving sheep, don’t look directly into their eyes; wolves and herding dogs do that and it instinctively makes sheep nervous. Don’t attempt to drive a flock faster than its usual walking speed; rushed sheep tend to scatter.

Moving sheep. Calm sheep move forward; frightened sheep move backward. Sheep prefer not to cross water or to move through narrow openings. They move uphill more readily than downhill and prefer to move with the wind rather than against it.

Catching sheep. To catch a sheep, herd the flock into a corner and keep it there by extending your arms or a crook to create a barrier. You can then carefully cut the desired animal out of the group using her flock mates’ bodies to prevent her from scampering away. (The smaller the pen, the easier it is to catch individual sheep.) Cornered, frightened sheep will try to squeeze through any small gap to escape and often attempt to jump to safety, usually toward whatever is blocking their way. A cornered sheep can hit an adult at chest height. Be careful!

Restraining sheep. To temporarily restrain a sheep, place one hand under her jaw and raise her head while steadying her opposite flank or her hindquarters with the other hand. A sheep has considerably more power when her head is down, so keep that head up to maintain control.

Signs of irritation. Annoyed sheep stamp their hooves, raise or nod their heads, or glare. They usually back a few paces before charging, although ewes sometimes bash each other from a standstill. Rams or pushy ewes may rub or bump humans with their foreheads. This is a sign of early aggression. Don’t allow it. (A sharp smack on the nose should discourage him.)

Be nice! Sheep remember bad experiences for up to two years. You will regret it if you lose your temper.

We often see farmers trying to lead a sheep by taking hold of its neck, of course also by the wool, and dragging it along. They make a hard task of it for themselves and certainly make it most unpleasant for the sheep. . . . [To lead a sheep from the left] place your left arm around its neck, and your right hand on the end of its tail-head, tickling it just a little there, and you will find that it will, as a rule, come your way very quickly, at times even faster than you care to have it come.

— Frank Kleinheinz, Sheep Management: A Handbook for the Shepherd and Student (1912)

A sheep who has rolled over onto her back is called a cast sheep. She can’t get up without assistance. Short-legged, widely built sheep with full fleeces and heavily pregnant ewes are especially prone to becoming cast, as are old, arthritic sheep. The heavy rumen of a cast sheep rests on her lungs, so cast sheep die of suffocation within an hour or so if they aren’t helped back up. Roll a cast sheep over so she’s propped up on her sternum, then when she’s ready, help her up, supporting her until she’s steady on her feet.

A cast sheep cannot right herself and needs immediate assistance.

Finally, here are a few additional facts to help you understand ovine behavior.