The Universal Declaration on Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights each address many fundamental aspects of the human existence. Together, these documents constitute the International Bill of Human Rights. Because human rights continually require evaluation and refinement, the United Nations and other groups propose supplemental human rights documents that address particular issues. For example, human rights groups have focused on so-called vulnerable populations, those segments of society that human rights activists believe need special attention. Reference to these segments of society as vulnerable populations, however, creates an undesirable and inappropriate impression of impairment. A more appropriate description is to refer to these segments as diverse groups that sometimes may require special attention within a human rights framework.

Human Rights and Diversity

Before analyzing human rights documents dedicated to particular segments of the population, we should ask, Do we need human rights documents specifically dedicated to a particular group? The general answer is that certain population groups have traditionally encountered discrimination on the basis of gender, national origin, ethnicity, age, or another classification. In addition, some of these population groups (such as children) require special attention to avoid potential exploitation.

In virtually all societies, women encounter an array of obstacles in obtaining many of the same rights and benefits as those held by men. For instance, those who hold political and economic power are more likely to be male than female. The male domination of power tends to omit a woman’s perspective on particular issues, which can often lead to discriminatory results.

Along with women, children also receive special attention in the area of human rights. The maturity level of children cannot match that of their elders, who must make sure to protect children.

Other diverse groups include cultural, ethnic, and religious minorities living in the mainstream of their societies. Native Americans, Roma in Europe, Palestinians in Israel and other Middle Eastern countries, and Catholics in Northern Ireland all are groups outside the mainstream or dominant society. They thus may need special attention regarding human rights, especially when their diversity leads to discrimination or other negative outcomes.

The realities of age and disabilities also require special attention. The older an individual is, the more likely he or she is to face discrimination and exploitation because of the frailties associated with advanced age. An individual with a physical or mental disability also needs special protection when that disability inhibits activities readily available to those without the disability.

Certainly, governments are aware of this increased likelihood of oppression or exploitation and have enacted laws to help level the playing field for those needing special attention. In the United States and other countries, laws prohibit discrimination in connection with employment, real estate transactions, access to financial credit, and availability of public accommodations on the basis of gender, national origin, age, disability, and other classifications (e.g., Illinois Human Rights Act 1992). These laws are intended to protect diverse groups in situations most likely to affect significant events encountered by individuals who belong to the listed segments of society. Children receive special protection in laws prohibiting abuse and neglect.

Many of these laws, however, address only certain situations and do not provide a sufficiently broad and coherent approach to those groups in a human rights context. Laws in the United States prohibiting discrimination against gender and other classifications often do not apply to small employers or private clubs (see Illinois Human Rights Act 1992). This exclusion allows many acts of discrimination to continue without consequence. Even when laws prohibiting discrimination apply, filing complaints can be time-consuming and cumbersome and are often beyond the complainant’s expertise. Furthermore, large companies and organizations typically have the resources to hire legal professionals and often go to considerable expense in contriving responses to allegations of discrimination. In other words, charges of discrimination may fail in countering unlawful practices and instead may promote defending and upholding current practices. Occasionally a law firm might undertake a class action case against a mighty icon of corporate enterprise on behalf of a large group of plaintiffs, but few individuals have the necessary resources to battle large corporations. As Richard Grossman, a historian of corporations, law, and democracy, observed:

There’s a corporate class that has enormous wealth, and the power of law behind it, and it dominates the way issues are framed. I mean, is it really true that the majority of the American people over the last twenty-five years didn’t want a major transition in energy to move to efficiency and solar, didn’t want universal health care, but wanted pig genes in fish? (Conniff 2002, 34)

To counter existing power structures, particularly those relevant to various segments of society, a different way of approaching discrimination and other violations of the human existence should be established. Human rights principles provide a means with which to alter the overall structures that allow discrimination and other violations. Unfortunately, laws can sometimes harden attitudes if compliance with them requires significant economic and political change. Instead of always relying on laws to assist vulnerable populations, attention should be directed to the mind-set of those who control societal institutions. Regardless of the circumstance, every individual is entitled to an existence that encompasses human rights. The starting point for any government, corporation, school, religious group, and other entity should be to focus on satisfying human rights, without feeling coerced into doing this. This initial step is particularly relevant to diverse populations.

The Department of Human Rights: Hazardous to Health?

Many states have formed agencies to investigate violations of “human rights.” For instance, Illinois has the Illinois Department of Human Rights, which investigates certain complaints relating to alleged discrimination on the basis of age, gender, national origin, disability, religion, and sexual orientation.

To claim discrimination, a “complainant” must allege facts indicating that some action, usually by an employer, resulted in the loss of a benefit. The complainant must also present facts showing that the action taken was based on the complainant’s age, gender, national origin, disability, religion, or sexual orientation. The authority of the Illinois Department of Human Rights to investigate complaints of discrimination is limited to employers that have at least ten employees, but it may also investigate complaints against public facilities and landlords. Private clubs are exempt from investigation.

The department’s effectiveness in preventing discrimination may be minimal. Large companies often make it extremely difficult to purse these complaints unless the complainant has a lawyer (which costs money). In addition, investigators usually demand hard facts as to the alleged discrimination, which generally is subtle in nature and not obvious.

An unintended result of the department’s activities may be to entrench discriminatory practices, especially when the complaints are dismissed or settled with no significant consequence to the alleged offender. Unless employers and other entities find it costly to discriminate, the discriminatory practices most likely will continue. Government agencies assigned to investigate discriminatory practices may not have sufficient resources to actually do the job they are required to do. In addition, complainants may find it easier to abandon their cause once they discover how difficult (and expensive) it can be to prove discrimination and to persevere against an employer or other entity. Of course, anyone who files a complaint must be prepared to face the wrath of his or her employer (and perhaps even of coworkers), even though retaliation by an employer is prohibited.

The bottom line for those who wish to file complaints of discrimination is to be prepared for a struggle, for discrimination in the eyes of the complainant is not the same as discrimination in the eyes of the alleged offender.

While the International Bill of Human Rights frequently addresses these different groups, additional human rights documents provide greater context and detail. This chapter looks at women as a segment of society that requires special attention, and the next chapter considers additional groups and specific documents relating to those groups.

Women and the Human Rights Framework

A primary goal of the social work profession is to work with diverse populations, the largest being women and girls. Historically, this population has encountered significant discrimination:

Throughout history, with rare exceptions, women have been relegated to second-class status, their lives controlled, regulated, and limited. In the United States, women were denied the right to vote, attend school, own property, keep their wages, or obtain custody of their children. Although gains have been realized, largely because of the first and second waves of the women’s movement, much remains to be done. (NASW 2009, 367)

Women perform two-thirds of the world’s work but earn only one-tenth of all income and own less than one-tenth of the world’s property (Human Rights Watch World Report 2001, 456). Two-thirds of the 110 million children in the world who are not receiving an education are girls. Women constitute the majority of the world’s poor as defined by income level. Seventy percent of the world’s 1.3 billion people living in poverty are women. The number of women living in absolute poverty (i.e., life-threatening poverty) has risen by 50 percent over the last two decades, as opposed to 30 percent for men (Human Rights Watch World Report 2001, 456). Because of their greater incidence of poverty, women do not always receive adequate health care. Socioeconomic factors, as well as chance genetic inheritance and the geographical availability of nutritional resources, determine an individual’s health status. Relatively affluent people and those content with their lives enjoy better health status than do impoverished—and oppressed—people who suffer a poor self-image in addition to the disrespect they may encounter in their own communities.

Today, women remain economically disadvantaged in most countries, which makes them both vulnerable to violence and unable to escape it (Shah 2007). The correlation between gender and poverty is a problem for all countries. Even when women have jobs, many obstacles make their lives more difficult than men’s. Working women often are also responsible for child care and management of the household, which effectively requires them to do double duty (Rosen 2007). And then there is the pay gap, with average hourly wages for women in low-skilled industries being generally much less than those for men (Goldstein 2009).

Reverse Gender Discrimination: A Human Rights Perspective

Consider the typical situation of what the legal profession in the United States calls reverse discrimination as it relates to gender. A male applies for a well-paid job at a major company or applies for a coveted spot as a student at a prestigious university. The company or university denies the application but accepts a candidate who is female with apparently “lesser” qualifications. The male cries foul. “How can this be? I am more qualified. Just look at my experience, excellent test scores, and other attributes.”

Even if the male can justify his belief of superior credentials, a difficult matter to evaluate, does he have a claim to the job or university placement? Past discriminatory practices relating to gender should not create a basis for deciding who gets a job or university placement. But continuing practices that exclude women and girls from being considered on an equal footing with males violates human rights principles. If those in control of companies, universities, and other organizations fail to welcome gender or other diversity, then that is a human rights violation. At times, it may appear that the male has reason to claim that his human rights are being violated because of reverse discrimination. In most instances, though, this will not be the case, since human rights principles require the inclusion of women and girls in societal organizations. It is not a question of reverse discrimination but a question of fulfilling a human rights obligation to include women and girls in structures in which they traditionally have been absent or minimally present.

This is not to say that the male never has a claim of discrimination. When women dominate a profession or occupation, males should also be given the same opportunity to participate in those fields. Of course, many of those fields are low paying or have insufficient prestige to attract males (e.g., secretaries, receptionists, nannies). But males should certainly be welcome in areas dominated by women and not encounter discrimination.

Women’s Subordination and Exclusion

In societies around the world, female-gendered status is viewed as inferior and subordinate to male-gendered status (Bunch 1991). In fact, societies have modeled their gender-role expectations on these assumptions of the “natural order” of humankind. Historic social structures reflect this gender difference of male dominance and female subordination, including

- The organization and conduct of warfare.

- The hierarchical ordering of influential religious institutions.

- The attribution of political power.

- The authority of the judiciary.

- Influences that shape the content of the law. (Bunch 1991)

In most, if not all, societies, women assume inferior, servile social roles. The historic subordination, silencing, and imposed inferiority of women is in fact not simply a feature of society but a condition of society (Cook 1995). Legal precepts traditionally exclude women from centers of male-gendered power, including legislatures, military institutions, religious orders, universities, medicine, and law. In social work, although women constitute the majority of social workers, men hold the vast majority of leadership positions in teaching social work (Bricker-Jenkins, Hooyman, and Gottlieb 1991).

Focus on Upper-Class Women Misses the

Larger Human Rights Issue

“To hear the media tell the tale, the central problem facing working women today is the question of whether they should leave their professional careers to raise children” (Friedman 2009, 18). The reality, though, is that at least in the United States, women who can “opt out” of the working world account for only about 10 percent of working women aged twenty-five to forty-four years (Friedman 2009, 18).

Most families do not have the option of either parent not working, especially considering the number of single-parent families, most of which are headed by women. For newspapers and other media to focus on professional women who can afford to stay at home is simply irresponsible journalism, as it ignores significant human rights issues concerning social welfare.

While women can readily understand their lack of power in relation to men, women also encounter diversity of power within their own gender. For instance, an upper-class married woman will likely have greater privileges in society than will an unmarried or even a married woman reliant on public assistance. The upper-class woman obviously has many more doors open to her in regard to housing, education, esteem in the community, and other opportunities. Such an imbalance of power does not occur simply at the individual level; society, government, religious institutions, and other forces maintain this imbalance, which is frequently directed against particular groups, including those based on income.

A woman’s access to resources, work, housing, education, and other advantages often determines her level of power. For that reason, when considering the application of human rights, social workers should always recognize that differences in power among and between groups can result in discrimination and inequality.

Women throughout the world share many experiences of violations of their rights. A human rights perspective helps illuminate the complicated relationship between gender and other aspects of identity such as race, class, religion, age, sexual orientation, disability, culture, and immigrant status. The types of discrimination and violence against women and girls are usually shaped by how gender interfaces with those aspects of identity (Bunch and Frost 2000). The absence of women in public office and decision-making positions may indicate cultural discrimination. The norms of a society may dictate that women do not belong in those positions. Class distinctions may also determine whether a girl child has access to health care or education. While the particular issue concerning women’s rights might vary from country to country, the theme remains the same: women and girls have less value than men and boys.

The notion that human rights are universal and belong to all people is centrally connected to principles of equality. Everyone, everywhere, is born with the same human rights, and women should have the same opportunities to enjoy them. In a human rights context, equality does not necessarily mean treating everyone in the same manner. When people are in unequal situations, treating them in the same manner invariably perpetuates, rather than eradicates, injustices (Van Wormer 2001). Women often require different treatment than men in order to enjoy the same rights. To enjoy the human right to work, women may require child care and recognition of the work they typically do in the home. A woman’s right to work would then require measures to balance the unequal situations between men and women. Emphasis on the role of men in raising children and doing work at home could help women achieve this human right. Merely enacting a law stating that women have the same right to a job as men does little in helping women exercise their human right to work. Consequently, human rights are not gender neutral. In addressing violations of human rights against women, social workers should recognize the unequal positions of women and men in society and that they have become the cultural norm.

The Financial Crisis of 2008:

A Male-Only Affair?

Media coverage of the financial crisis beginning in 2008 illustrated the subordination of women to men in the area of what makes the world go ’round. The bankers, government officials, corporate and union leaders, and other leading figures involved in the financial downturn were nearly always men. Rarely did a woman appear on television, radio, or in newspapers to discuss the financial crisis. It was as if men controlled all the levers in discussions about the crisis.

This lopsided gender view of a major world event said much about the reality of affairs in financial markets: Men call the shots.

Women’s Rights Are Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights does not contain any provisions specific to women. The language of the declaration refers to man and uses the pronoun he when referring to individuals. But during the three years in which representatives of countries drafted the declaration, they exchanged thoughts about women and the rights of women (Morsink 1999). Although the declaration introduced innovative and progressive rights for everyone, the articulation of those rights still reflects a male-dominated world by incorporating generally male perceptions and priorities. After the Universal Declaration was adopted in 1948, central concerns about the male focus persisted. The concept of human rights had not been expanded sufficiently to account for the social, economic, cultural, and political circumstances in which a woman’s identity is shaped and experienced (Human Rights Watch World Report 2001, 455). Essentially, the failure of human rights documents and principles to sufficiently highlight the equal status of women to men led to a need to specifically recognize that “women’s rights are human rights.”

The movement to promote women’s rights as human rights began in the years following the Universal Declaration. In 1966 the United Nations adopted two international covenants that gave more force to human rights as specified in the declaration: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. These documents did not highlight, however, the pressing need to address women’s rights as human rights. Countries ratifying those treaties signified a greater commitment to human rights, at least on paper, but their commitment did not include the specific recognition of women’s entitlement to human rights.

In 1975, for the first time, the United Nations held a world conference on women in Mexico City (UN 1976), at which those attending linked the oppression of women to their inequality. Leaders at the conference also urged governments to eliminate violence against women, acknowledging that to improve their status, much needed to be accomplished. Therefore, the UN proclaimed the next ten years as the Decade of Women (Reichert 1998).

Five years after its first world conference on women, in 1980 the UN held the second UN World Conference on Women in Copenhagen (Reichert 1998). At this conference, delegates from the UN endorsed the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) (CEDAW 1979; UN 1980). The purpose of this convention was to place women on an equal footing with men in any field, including the political, economic, social, and cultural arenas. Social workers have called this convention the Magna Carta for women’s human rights (Wetzel 1993). Under its provisions, thirty days after the twentieth country approved the convention, CEDAW would come into force, which happened on September 3, 1981. At least 185 states have now approved the convention.

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of

Discrimination Against Women

The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women, or CEDAW, focuses on elevating the status of women to that of men in the area of human rights. Those states approving the convention acknowledge that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and subsequent international covenants all aim to eliminate discrimination on the basis of gender. But despite these various instruments, extensive discrimination against women continues to exist and “in situations of poverty women have the least access to food, health, education, training, and opportunities for employment and other needs” (CEDAW 1979). Those states party to CEDAW are convinced that the full and complete development of a country, the welfare of the world, and the cause of peace require the maximum participation of women on equal terms with men in all fields. They acknowledge that a change in the traditional roles of men and women in society and in the family is needed to achieve full equality between men and women. Thus those states approving CEDAW agree to adopt measures that would eliminate gender discrimination in all forms and manifestations.

CEDAW defines gender discrimination as follows:

Any distinction, exclusion, or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment, or exercise by women irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil, or any other field. (CEDAW 1979, art. 1)

Any distinction, exclusion, or restriction having the “effect” as well as “purpose” of discriminating would include unintentional as well as intentional discrimination.

CEDAW also requires states to take appropriate measures in all fields, particularly the “political, social, economic, and cultural fields, to ensure the full development and advancement of women.” States also must take all appropriate measures to “modify the social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women, with a view to achieving the elimination of prejudices and . . . other practices which are based on the idea of the inferiority or the superiority of either of the sexes or on stereotyped roles for men and women” (art. 5[a]). States must suppress all “forms and traffic in women and exploitation of prostitution of women” (art. 6).

Other Provisions of CEDAW

In addition to general goals of achieving gender equality, those states party to CEDAW are to specifically address issues in the fields of education, employment, health care, and economic benefits. Men and women must have equality in civil matters, including the right to conclude contracts and administer property. Women shall also have the same rights as men with regard to freedom of movement and choice of residence. The states shall also eliminate discrimination in marital and other family matters, allowing women equal rights with respect to choosing a spouse, choosing a family name or profession, and owning and disposing of property.

CEDAW established its Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women to evaluate the progress made in implementing the convention (art. 17). States should submit periodic reports on measures taken to effect provisions of CEDAW to the secretary-general of the United Nations for consideration by the committee (art. 18). There is an optional settlement provision for resolving disputes between two or more states concerning the interpretation or application of CEDAW (part VI). Another optional provision allows individuals to submit complaints of alleged violations of rights to the committee. Under this optional provision, the committee could initiate an inquiry into alleged serious violations of rights protected by CEDAW against a state party to CEDAW.

Status of CEDAW

Most countries of the world have now approved CEDAW, thereby obligating their government to enforce the convention’s provisions, except for any reservations cited by the government. One notable holdout in approving CEDAW is the United States. Even though President Jimmy Carter signed the treaty in 1980, the U.S. Senate has yet to ratify it. As an indication of how popular this human rights document was among some senators, on International Women’s Day in 2000, Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina publicly vowed never to allow the Senate to vote on CEDAW. Instead, he promised to leave the treaty in the “dustbin” for several more “decades” (Human Rights Watch World Report 2001, 457). Senator Helms’s vow seems to have become reality.

Why do U.S. senators oppose CEDAW? The answer is that acceptance of the convention would require significant changes in the current laws concerning discrimination against women. For instance, CEDAW goes further than many U.S. laws in prohibiting discrimination within the private sector. That is, private entities often enjoy loopholes in current discrimination laws, which CEDAW would end. In fact, CEDAW would actually require governments to take positive measures to eliminate discrimination. This broad-based approach to ending gender discrimination does not always find favor among lawmakers. What would be the cost to businesses and agencies if they had to comply with every relevant provision of CEDAW? What would be the cost to government? What would be the cost to individuals? How could these costs be met? Complying with several layers of government regulations against discrimination would require substantial resources. But this cost analysis also overlooks key points in regard to any type of discrimination: What are the economic, political, social, and cultural costs if a society allows discrimination to continue, particularly against a group as numerous as women? Is this cost any less than that required to take positive steps against discrimination? Not allowing one-half the world’s citizens to fully use their intellectual and social potential because of obstacles imposed by social or cultural norms causes tremendous damage to world societies. Recognition of that fact is the basis on which the drafters of CEDAW approached the issue of discrimination against women.

Other U.S. objections to CEDAW pertain to birth control, abortion, and other family-planning issues. Even though President Barack Obama has expressed his desire to see CEDAW ratified, obtaining the approval of sixty-seven senators to ratify the convention in a time of financial difficulties does not appear likely.

Even though most countries have approved CEDAW, many have placed “reservations” or conditions on their acceptance of the provisions (Division for Advancement of Women 2009). For instance, Algeria has adopted CEDAW but reserves the right to enforce its family code over CEDAW’s provisions. One place in which the Algerian family code may conflict with CEDAW is the code’s restrictions on the residence of women. Australia has placed a reservation on the enforcement of CEDAW regarding paid maternity leave: it will not always provide paid maternity leave, even though CEDAW requires this benefit. Ireland reserves the right to provide more favorable benefits to women than men when Irish law requires this different treatment. Malaysia restricts the application of CEDAW when it would conflict with Malaysia’s federal constitution and sharia law. Mexico has agreed to enforce CEDAW in line with its economic resources. The United Kingdom places a reservation on CEDAW so that it will not apply to its royalty, including determination of succession.

Many of the stated reservations to CEDAW preserve cultural or religious traditions or require consideration of economic resources. Some countries also reserve the right to favor women for social welfare benefits and determination of child custody. The positive aspect of so many countries adopting CEDAW is the clear recognition that discrimination against women is not right. But by placing reservations on the enforcement of CEDAW, those countries that have formally approved CEDAW may not actually enforce key provisions of the convention.

Developments After CEDAW

Events after CEDAW continued to highlight its goals. In 1985, the third World Conference on Women was held in Nairobi, with the purpose of evaluating the current status of women. The conference delegates concluded that much still needed to be done and devised strategies for improving conditions for women. The final document of the Nairobi conference, known as the Nairobi Forward-Looking Strategies for the Advancement of Women, identified areas of concern to women and children, including violence, poverty, health, and education (Reichert 1996, 1998). Key points of this documents state that

• Women’s universal oppression and inequality are grounded in a patriarchal system that ensures the continuance of female subservience and secondary status everywhere.

• Women do two-thirds of the world’s work, yet two-thirds of the world’s women live in poverty. This work is usually unpaid, underpaid, and invisible. Women’s fiscal dependency thus is perpetuated, even though women do almost all the world’s domestic work, as well as work outside the home, and grow half the world’s food.

• Although women are the world’s peacemakers, they have no voice in arbitration. War takes a heavy toll on them and their families as they struggle to hold them intact in the face of physical and mental cruelty that leaves more women and children tortured, maimed, and killed than men in combat.

• Sexual exploitation of girls and women is universal, often resulting in sexual domination and abuse throughout women’s lives.

• Women provide more health care (both physical and emotional) than all the world’s health services combined. Women are the chief proponents of preventing illness and promoting health. Yet women enjoy fewer health care services, are likely to experience chronic exhaustion due to overwork, and are likely to be deprived emotionally and physically by their men, their families, their communities, and their governments (Wetzel 1993).

• Women are the chief educators of the family; yet women out-number men among the world’s illiterates at a ratio of three to two. Even when educated, women generally are not allowed to lead.

The Forward-Looking Strategies document also viewed domestic violence as a learned behavior that would harm future generations. Delegates urged governments to increase antiviolence services for women and to hold perpetrators of violence legally accountable.

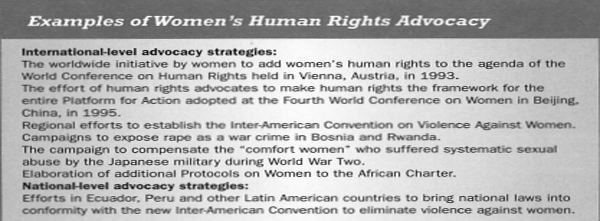

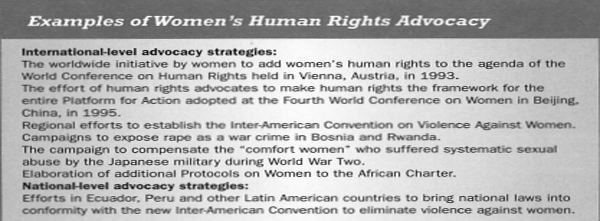

After the conference in Nairobi, the notion that “women’s rights are human rights” became the central tenet of thousands of advocates all over the world. In 1993, at a world human rights conference in Vienna, women from all over the world presented UN delegates with a petition that demanded the recognition of violence as an abuse of women’s rights. The final declaration at the Vienna conference affirmed that women’s rights are human rights (Heise 1995), which for the first time, many governments officially recognized (Bunch 1995). Gender-based violence and all forms of sexual harassment and exploitation, including those resulting from cultural prejudice and international trafficking, were acknowledged as incompatible with the dignity and worth of the human person and thus must be eliminated (Vienna Declaration 1993). While many statements flowed from the Vienna conference, its overriding significance clearly was the recognition that “the human rights of women and the girl child are an inalienable, integral, and indivisible part of universal human rights.”

Two years later, in 1995, at the World Summit for Social Development, governments acknowledged that to combat poverty and social disintegration, women would have to attain equality and that poverty was a form of violence against women (UN 1995).

Finally, in September 1995, the much-publicized fourth UN World Conference on Women took place in Beijing. At that conference, delegates realized that many of the strategies developed ten years earlier at Nairobi to promote the status of women and children had not been effective. Women continued to be affected disproportionately by violence, poverty, illiteracy, and poor health, and they still occupied only a small minority of leadership positions. In the hope of accelerating progress in advancement of women’s rights, delegates adopted a final document, referred to as the Platform for Action (PFA), which expressly states that women’s rights are human rights. The platform covers twelve areas of concern affecting the well-being of women and girls. In addition to violence, the platform addresses poverty, health, armed and other conflicts, education, economic participation, power sharing and decision making, national and international mechanisms, mass media, environment and development, and the social role and treatment of girls (UN 1996). The PFA is the most supportive official statement on women ever issued by the United Nations and reflects the sentiment that all issues are women’s issues.

The PFA reflects an extensive grassroots effort by nongovernmental organizations and women from all areas of the world, not simply economically developed countries. The platform addresses the oppression of women at all societal levels and provides a comprehensive strategy for the advancement of women. One of its major positions is elevating women’s rights over cultural norms. Nonetheless, it has a nonbinding legal status and often cumbersome and unclear wording, and no government is obligated to follow its directives or strategies. Despite these shortcomings, the platform still is an admirable effort to present an agenda for the advancement of women in society.

After the Beijing conference, countries began to address areas of critical concern listed in the PFA. An evaluation process known as the Beijing + 5 Review was created to determine whether progress had been made five years after the conference. The Beijing + 5 Review involved a multitude of voices and perspectives, with the primary importance attached to actions, as opposed to words. In this respect, governments became aware that they had made little progress toward fulfilling the Beijing promises and were reluctant to make more commitments. The assessment of women’s status also became more complex, with significant improvements in some areas for some women offset by economic decline and growing violence in others (Meillon and Bunch 2001, 134). Backlash may have entered into the governments’ reluctance to pay greater attention to the PFA. Political leaders may have tired of hearing about women’s difficulties and acted accordingly. The aspect of “globalization” also played a more significant role in the Beijing + 5 Review, with women in less economically developed countries encountering more conflict with women in wealthy countries. When resources are insufficient to implement even basic human rights, how can the focus be on equality in the workplace or other concerns typically found in wealthy societies?

Overall, the Beijing + 5 Review reaffirmed the Platform for Action, and governments pledged to implement areas of concern in the PFA. As with any area of human rights, women’s rights can be enshrined in gold but will have little meaning if those rights are not recognized. Without understanding human rights and their importance, laws simply are not enough to ensure the actual recognition of human rights, especially for a vulnerable population like women.

Social Work Symposium on Human Rights and

Violence Against Women

From their inception, the UN’s world conferences on women were structured to include both governmental and nongovernmental groups. Parallel to each of those conferences, nongovernmental organizations have held their own forums from which to present recommendations to conference delegates. The NGO Forum on Women at the Beijing conference included more than 30,000 participants, mainly women, from every corner of the world.

Earlier UN conferences on women had no organized meeting of social workers (Reichert 1998), even though the conferences’ underlying themes addressed issues of great importance to social workers. To emphasize the importance of the social work profession in issues presented at the 1995 conference, Dr. Janice Wetzel organized a social work symposium on human rights to meet at the NGO forum. Joining Dr. Wetzel in sponsoring the symposium was the Women’s Caucus of the International Association of Schools of Social Work, an NGO having consultative status with the United Nations. This symposium represented the first organized gathering of social workers in conjunction with a UN world conference on women (Reichert 1998), and its main goal was to bring together social workers from all parts of the world to exchange ideas and information.

Two hundred women and men from twenty-seven countries attended the symposium, which highlighted a human rights approach to counter the view that violence against women is a cultural norm. By emphasizing women’s rights and human rights, participants hoped to create a common thread among social workers in response to violence. The symposium also encouraged governments to consider cultural background when taking measures against violence. Following the symposium, volunteers drafted a resolution to schools of social work and delegates attending the UN conference. This resolution consisted of a synthesis of programs initiated by women for personal, social, and economic development (Wetzel 1993, 1996):

1. Look to the women: listen to the women: Always begin with the personal experiences of indigenous and local women, generalizing them to state, national, and international policies so that the connections between all forms of violence become clear.

2. Require economic self-determination: Women must lead and define economic and development policies and programs that affect communities. Current policies leave women with a heritage of destruction in health, environment, education, livelihood, culture, and autonomy. Investment priorities must be in the human community.

3. Free women from fear and domination: War, dislocation, and state-sponsored violence, as well as violence in the street and in the home, feed the epidemic. It is a fundamental human right of all women and children to live with respect and without fear.

4. Value all women’s work: The invisibility and undervaluing of women’s work inside and outside the home lead to women’s status as the poorest, least educated, and most vulnerable to health problems, both physical and mental. Overwork and lack of pay impede human progress.

5. Place women in decision-making positions: With women’s personal development, relevant social development and action are not only possible but also appropriate and successful.

6. Promote shared responsibilities in all forms of family and social partnerships: Human rights include equal sharing of home care and family care. Respect for all forms of human families is basic to promoting human rights and building healthy communities.

7. Invest in health care and education: The prevention of women’s physical and mental illness requires access to appropriate and affordable health services. Literacy, numeracy, and other forms of basic education improve women’s economic status, delay pregnancies, and better educate future generations.

8. Educate all women regarding their legal rights and other laws pertinent to them: Include in legal education the execution of critical analyses and the development of corrective laws and policies.

9. Promote positive perceptions of and by women: Within the context of human rights, provide opportunities for women to share experiences, acknowledge differences, and recognize the value of diversity.

10. Press for relevant gender-specific data collection and research: Consider new models, such as participative action research, in which women themselves select the issues and guide the design, analyses, and implementation of results.

These ten elements guide social workers all over the world in addressing women’s issues and human rights. In conjunction with CEDAW, the Platform for Action, and other human rights documents, the resolution offers schools of social work a valuable tool in addressing human rights of women.

Figure 5.1

The Importance of Women’s Human Rights to the

Social Work Profession

In bringing a gender perspective to the understanding of rights, women have struggled to ensure that all human rights—civil, political, economic, social, and cultural—are equally guaranteed to women. The promotion of gender perspective has resulted in increased recognition of interdependence among all human rights. By examining human rights through women’s eyes, critical questions emerge: Who in society is a citizen? What are the criteria for consideration as a citizen? Are issues and themes accepted as “legitimate” political debate truly representative of the concerns of the majority of its citizens? All these questions relate to the recognition that women’s rights are human rights.

How is the movement to recognize women’s rights as human rights relevant to the social work profession? The profession’s primary mission is to advocate and work on behalf of vulnerable populations. In regard to women, a human rights perspective helps illuminate the complicated relationship between gender and other aspects of identity such as race, class, religion, age, sexual orientation, disability, culture, and refugee or migrant status.

Viewing women’s and girl’s lives within a human rights framework provides a new perspective. For example, the movement to draw attention to violence against women and girls came from article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The concept of human rights has helped define and articulate women’s and girls’ experiences of violations such as rape, female genital mutilation, and domestic violence. Understanding such violence in terms of human rights establishes that states and individuals are responsible for such abuse, whether committed in the public or the private sphere. A human rights perspective also addresses the issue of how to hold governments and individuals accountable when they are indifferent to such abuses. Human rights give women all over the world a common vocabulary by which they can define and articulate their specific experiences, entitling each person to human dignity.

The National Association of Social Workers recognizes the importance of human rights to women’s issues and supports the following:

- Ratification by the United States of CEDAW.

- International programs that address women’s rights as human rights, including involving women in each country in defining their needs, identifying their oppressions, and developing programs that meet their needs.

- Increased attention by social work education to problems facing women around the world, often due to the effects of globalization and colonization, as well as traditional patriarchal structures. (NASW 2009, 371)

To be relevant to women or any group, human rights need official recognition by governments. Knowing about human rights is only the first step toward recognizing those rights. Legal processes must also actively enforce those rights. Unless women’s rights are established as human rights, the role of women will always be secondary in overall societal structures. By promoting human rights for women, the social work profession will be working toward its mission of assisting vulnerable populations.

Questions

1. Should women be entitled to special human rights considerations?

2. What is meant by the phrase “women’s rights are human rights”?

3. Give an example of how the difference of power can lead to gender discrimination.

4. What is the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women? Do you believe this convention is necessary to eliminate discrimination against women? Discuss.

5. Should the United States become a party to CEDAW? Why or why not?

6. What is the significance to social work of the Social Work Symposium held in China during the fourth UN World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995?

7. Discuss the Platform for Action. Is the PFA important to the social work profession?

8. Do you believe the status of women has improved since the 1995 Beijing conference?

9. How can a human rights perspective promote the understanding of women’s issues from a global perspective?

References

Bricker-Jenkins, M., N. Hooyman, and N. Gottlieb, eds. 1991. Feminist Social Work Practice in Clinical Settings. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Bunch, C. 1991. Women’s rights as human rights: Toward a re-vision of human rights. In Gender Violence: A Development and Human Rights Issue, ed. C. Bunch and R. Carrillo, 3–18. New Brunswick, NJ: Center for Women’s Global Leadership.

——. 1995. Beijing backlash and the future of women’s human rights. Health and Human Rights: An International Quarterly Journal 1 (4): 449–53.

Bunch, C., and S. Frost. 2000. Women’s human rights: An introduction. Available at www.cwgl.rutgers.edu/globalcenter/whr.html (accessed September 21, 2010). Originally published in Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women: Global Women’s Issues and Knowledge.

Conniff, R. 2002. The Progressive interview: Richard Grossman. The Progressive, March, pp. 32–36.

CEDAW. 1979. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. G.A. Res. 34/180, U.N. GAOR, 34th sess., supp. no. 46 at 193, U.N. Doc. A/34/46, adopted September 3, 1981. New York: United Nations.

Cook, R. 1995. Gender, health, and human rights. Health and Human Rights: An International Quarterly Journal 1 (4): 350–66.

Friedman, A. 2009. When opting out isn’t an option. American Prospect, June, p. 18.

Goldstein, D. 2009. Pink-collar blues. American Prospect. June, pp. 19–21.

Heise, L. 1995. Violence against women: Translating international advocacy into concrete change. American University Law Review 44: 1207–11.

Human Rights Watch World Report. 2001. Events of 2000. New York: Human Rights Watch.

Illinois Human Rights Act. 1992. 775 ILCS 5/1–101 et. seq.

Morsink, J. 1999. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Origins, Drafting, and Intent. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

NASW (National Association of Social Workers). 2009. Social Work Speaks: National Association of Social Workers Policy Statements, 2009–2012. 8th ed. Washington, DC: NASW Press.

Reichert, E. 1996. Keep on moving forward: NGO Forum on Women [4th UN World Conference on Women], Beijing, China [1995]. Social Development Issues 18 (1): 61–71.

——. 1998. Women’s rights are human rights: A platform for action. International Social Work 15 (3): 177–85.

UN (United Nations). 1976. Report of the World Conference of the International Women’s Year. June 19–July 1975, Mexico City. United Nations Publication no. E.76. IV.I (E/Conf.66/34). New York: United Nations.

——. 1980. Report of the World Conference of the United Nations Decade for Women: Equality, Development, and Peace. July 14–30, 1980, Copenhagen. United Nations Publications no. E.80.IV-3 (A/CONF. 94/35). New York: United Nations.

——. 1995. World Summit for Social Development. Washington, DC: U.S. State Department.

——. 1996. The Beijing Declaration and the Platform for Action. 4th World Conference on Women, September 4–15, 1995, Beijing. New York: UN Department of Public Information.

Van Wormer, K. 2001. Counseling Female Offenders and Victims: A Strengths-Restorative Approach. New York: Springer.

Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. 1993. Second World Conference on Human Rights. New York: UN Department of Public Information.

Wetzel, J. 1993. The World of Women: In Pursuit of Human Rights. London: Macmillan.

——. 1996. On the road to Beijing: The evolution of the international women’s movement. Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work 11 (22) (summer): 221–36.