AFTER YEARS OF working with abuse survivors and listening to them talk about their symptoms, I discovered the key that unlocked the elusive mystery of dissociation—the presence of five core symptoms. These symptoms are universally experienced by people, to varying degrees, after exposure to trauma.

The core dissociative symptoms are:

amnesia

depersonalization

derealization

identity confusion

identity alteration

Amnesia is the inability to account by memory for a specific and significant block of time that has passed. You may think of it as “gaps” in memory or “lost time”

Depersonalization is a feeling of detachment from yourself or looking at yourself as an outsider would. You may also feel separated from parts of your body or feel detached from your emotions, like a robot or an automaton.

Derealization is a feeling of detachment from your environment or a sense that the environment is unreal or foreign, often involving people who were previously familiar to you.

Identity confusion is a feeling of uncertainty, puzzlement, or conflict about who you are. You may feel as if a continuing struggle is going on inside you to define yourself, including your sexual identity, in a particular way.

Identity alteration is a shift in role or identity, accompanied by such changes in your behavior that are observable to others as speaking in a different voice or using different names. You may experience the shift as a personality switch or loss of control over yourself to someone else inside you.

After identifying these major symptoms, I developed ways to evaluate their severity, by crafting a concise definition for each that characterized its essential features. In particular, I used the terms “identity confusion” and “identity alteration” to describe how trauma affects one’s sense of self. Equipped with the SCID-D, clinicians could, for the first time, assess all five symptoms comprehensively to determine whether a person had a dissociative illness or not. Different constellations of these five core syndromes defined the particular dissociative disorder a person had.

dissociative amnesia (loss of memory for your identity or past, characterized by the inability to recall important personal information)

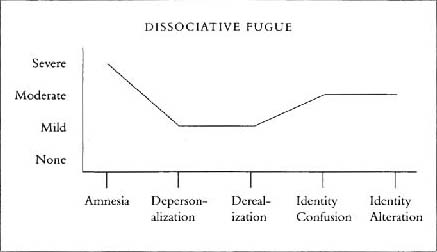

dissociative fugue (sudden, unexpected travel away from your home associated with identity confusion leading to distress and dysfunction)

depersonalization disorder (persistent and recurrent severe episodes of feeling detached from yourself, parts of your body, or your emotions, leading to distress and dysfunction)

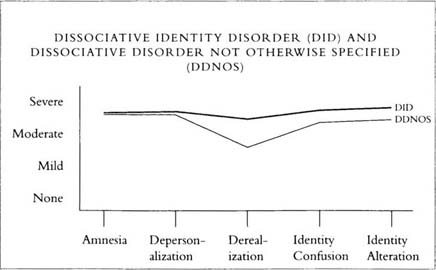

dissociative identity disorder or DID (the existence of distinct, coherent identities within yourself that are able to assume control of your behavior and thought)

dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (DDNOS, an early stage or less serious form of the other disorders that often precedes a diagnosis of DID)

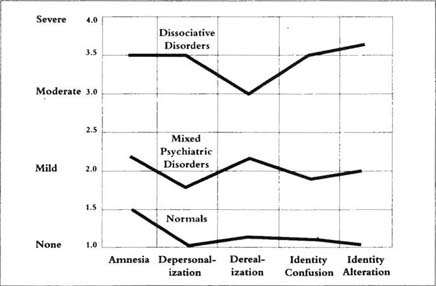

The SCID-D interview provides a well-defined snapshot of the health of a person’s trauma response system. At one end of the spectrum are people whose dissociative defense is normal. Their symptoms are mild—rare, of short duration, and not distressing or disruptive to their lives. In the middle of the scale are those with moderate symptoms that occur more frequently and last longer, including some that cause dysfunction or distress, and indicate the need for a professional assessment. Many people in this range have been in therapy for something other than a dissociative symptom or disorder—depression or panic attacks, for example—and will not enjoy a full recovery unless their dissociation is recognized and treated. At the opposite end are those with severe symptoms that are more frequent and result in more dysfunction than moderate symptoms, and are present in people with a dissociative disorder.

The most important distinction for you to make is between mild dissociative experiences that are normal and experiences that range from moderate to severe. If your symptoms fall anywhere in the moderate to severe range, you should have the full SCID-D done by a qualified professional who can make an accurate diagnosis. With appropriate treatment, the chances of recovery from a dissociative disorder are very good.

Determining whether your dissociative response is healthy or not depends upon your ability to recognize certain experiences—memory blanks, feelings of unreality, emotional numbness, out-of-body episodes, automatic movements, and the like—as signs of one of five core dissociative symptoms. Once you fully understand how and why these symptoms manifest themselves, you can identify your experiences of them and determine whether they’re normal or rise to a higher level of moderate to severe.

An accurate diagnosis of a disorder should be undertaken only by a specially trained clinician. The purpose of the material in the next chapters on the core symptoms is to tell you enough about them so that you’ll be able to understand and recognize your own experiences of them. After you’ve read all the material about each symptom, you can answer the questionnaire adapted from the SCID-D at the end of the chapter on that symptom. When you’ve completed each questionnaire, you’ll be able to assess whether your symptoms are serious enough to warrant seeing a therapist. If you’re in therapy now, you should draw these symptoms to your therapist’s attention, particularly if they’re at all disturbing, and ask to have the entire SCID-D done. The interview usually takes less than three hours. This little bit of time can save a person twenty years of misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

You’ll find that some of the items in the questionnaires are signs of normal dissociative symptoms. For example, forgetting where you put personal belongings like your keys or glasses is a normal kind of amnesia, and finding it hard to juggle all the different roles in your life is a normal form of identity confusion. Experiences like these shouldn’t be a cause for concern. If you’ve experienced any of the other items several times, particularly if the symptom is associated with dysfunction or distress, a more complete evaluation by a professional is recommended.

The following illustrations, reprinted from my Interviewer’s Guide to the SCID-D, will give you a graphic picture of how the presence of dissociative symptoms determines a disorder. The first four graphs show how the five core symptoms combine to form a particular dissociative disorder. The last one shows the wide divergence in the severity of symptoms between normal people and those with a dissociative disorder. Symptoms in normal individuals are mild or absent, whereas symptoms in people with a dissociative disorder are mostly moderate or severe. In the middle between the two groups are the “moderates”—people who have any one of a number of psychiatric conditions but have a higher degree of dissociative symptoms than normal people do. These symptoms are often unreported or overlooked in therapy to a patient’s detriment.

Your answers to the questionnaires will provide you with a preliminary SCID-D snapshot of your trauma response system. If you score a “mild” on all of the questionnaires, you can assume that your trauma response system is healthy and your dissociative symptoms are normal. If you rate a “moderate” or “severe” for any symptom, you would be well advised to see a therapist for a more complete evaluation. Identifying these symptoms in oneself and determining whether they are more than mild are crucial first steps for anyone in need of therapy and wanting the most effective care.

SCID-D Symptom Profiles of the Dissociative Disorders

Reprinted with permission from M. Steinberg. Interviewer’s Guide to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders-Revised (SCID-D-R). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1994.

SCID-D Symptom Profiles in Psychiatric Patients and Normal Controls.

Data from M. Steinberg, B. Rounsaville, D. Cicchetti. The structured clinical interview of DSM-III-R dissociative disorders: preliminary report on a new diagnostic instrument. American Journal of Pyschiatry (1990) 147, 76–82.

Reprinted with permission from M. Steinberg. Interviewer’s Guide to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders-Revised (SCID-D-R). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1994.