HARRY CONNICK, JR., the popular singer and pianist, can laugh about it now, but at the time it happened it was a monumentally humbling moment. He was performing his act to a sell-out crowd in a large club, singing a song he’d done countless times before, when he spotted one of his most revered idols in the audience and promptly forgot the lines. His mind was a complete blank. Forced to improvise, he gallantly made a joke of it and managed to limp through the piece to the end.

This kind of blank spell associated with “performance anxiety” is a form of mild dissociative amnesia or memory loss that happens to almost all of us when we’re under stress. Dissociative amnesia is different from the permanent loss of stored information, similar to the accidental erasure of a computer disk, that may occur in brain trauma. Amnesia in dissociation doesn’t wipe out the memory; it displaces it from awareness to unawareness. In mild amnesia, the temporarily misplaced material can usually be retrieved after the stress has subsided.

There are many conditions in which amnesia is natural or even necessary. If the mind were constantly required to process all the data accessible to memory on a conscious level, the result would be an inconceivable stimulus overload. As Nietzsche once said, “Without forgetting it is quite impossible to live at all.”

Memory can be considered the most essential part of human consciousness because we need to maintain a continuous memory of events before we can attach meaning to them. We can think of memory as the “language of identity” since our sense of self is typically constructed around a personal history. Our image of ourselves is dependent in large measure on how we remember our history of personal events, relationships, and beliefs, and on how we expect ourselves to respond to situations on the basis of past experience. Loss of memory or gaps in our personal history are often perceived as an assault on our sense of identity and can be worrisome or frightening. Since normal episodes of amnesia are widespread, it’s important to be able to distinguish these from moderate amnesia, which can indicate a problem, and the severe amnesia that occurs with a shattered sense of self.

Occasional, brief forgetfulness is a mild form of dissociative amnesia or absence of memory that happens to almost all of us when we’re under stress. The examples are legion. Who hasn’t run up the stairs to get something and forgotten what it was? How often have we met up with an acquaintance whose name we know but can’t recall, while it teasingly bounces around on the “tip of the tongue”? Someone asks us to recite the Pledge of Allegiance, and we forget the words in midstream. We’re so preoccupied that we forget to show up for a doctor’s appointment even though we had confirmed it earlier. Our mind wanders during a boring lecture or a run-on conversation, and we miss part of what is said.

One of the most familiar examples of normal dissociative memory loss is “highway hypnosis.” It can happen in two different ways. The road we’re driving on may be so familiar that we keep only part of our mind on it and arrive at our destination without remembering the ride. Or we can become so engrossed in other matters during the ride that we forget to take the right exit and “wake up” several exits past it, saying, “Where was my mind?”

Besides these widespread mild episodes of amnesia, there’s the blank spell that the intense pressure of a test or a job interview can bring on. Julia, a computer specialist, recalls “screwing up” when she was interviewed for a job by a personnel director she found very intimidating. “It was like facing a detective in a police interrogation room,” she says. “The man was like a block of ice. He shot questions at me and sat there stony-faced while I answered them. Then he asked me to solve a programming problem as a test of my skills. He left the room, but I was already so unnerved that I couldn’t remember the most basic steps. Under other circumstances it would’ve been a piece of cake.”

Alex, a twenty-nine-year-old graduate student who waits on tables part-time to help put himself through school, occasionally has the same kind of mild memory lapse. “The restaurant I work at is very trendy,” says Alex, “and there are always a dozen specials you have to remember with different combinations of ingredients and fancy sauces. I can usually rattle them off with no problem. But every once in a while I’ll get thrown off the track by the way someone at the table is staring at me, and my mind goes blank. It’s very disconcerting. I have to stop and look at this little crib sheet I keep, and it kills the whole effect.”

Many people are uncomfortable in the spotlight and are prone to stage fright, a common cause of a mild form of amnesia. For these people, giving a speech in public is as traumatic as a life-threatening event. Standing at the microphone with that sea of faces staring at them fills them with the dread of public humiliation. Instead of focusing on the content of the speech, they dissociate and draw a blank. Fortunately, training and practice in public speaking can help reduce the anxiety it provokes and lessen the likelihood of blanking out.

Time gaps are commonplace occurrences in dreaming. We may be in dream consciousness for hours and yet can usually remember only brief sequences from the dream. Candace, an advertising copywriter in her thirties, describes a typical experience of dream amnesia: “Sometimes I have these vivid dreams with all kinds of surprising twists and turns,” she says, “and when I wake up I don’t remember much of the dream at all. I know what it was about generally—let’s say, being chased from car to car on a train when I’m having an anxiety dream about meeting a deadline—but I can’t remember what led up to the chase or even who was chasing me. I’m left with more of a feeling about the dream than I am with a memory of what took place.”

Normal time gaps also occur when we temporarily lose our recall of what we were doing at some point in the day or the week but are able to remember the events or activities with some intentional effort. The theory is that although we have immediate memory for some things, for others it’s delayed. It can take a reminder of some kind—a ticket stub from a trip or another person’s mentioning something that happened during that period—to “jog” a delayed memory out of hiding.

Ben, a forty-six-year-old accountant from Boston who enjoys traveling, experienced a delayed memory of a site he’d visited on a trip—an episode that happens to many of us on occasion. “My wife and I were having dinner with some friends who’d recently returned from a vacation in Santa Fe,” he says, “and they were raving about a sculpture garden they’d seen on the way back from Taos. My wife said we’d seen it, too, when we were there, but I had no recollection of it. Then all of a sudden it came back to me when they started talking about the huge bronze animals that were there. It’s the Shidoni Sculpture Gardens in Tesuque, and it was one of the places on our tour. I was impressed by it at the time, but it just slipped my mind.”

These minor time gaps and brief memory blanks are widespread, generally benign, and no cause for concern. They can be annoying, but most of us accept the frustrations of this kind of everyday forgetfulness with good grace.

As a general rule, not remembering some of your childhood prior to age three is normal. Researchers tracing the development of ordinary amnesia have discovered that verbal memory for the first three years of life is fragmented. Infantile experiences are encoded in primitive prelinguistic form and can’t be retrieved normally by an adult whose encoding state is mostly a more highly developed linguistic one. Hypnosis can return an adult to more primitive levels of consciousness and may be related to reported memories of experiences in infancy. But infants don’t have the capacity to remember in the same way adults do. Amnesia, like all the dissociative symptoms, has its origins as a healthy defense against being psychologically overwhelmed.

When amnesia is moderate rather than mild, it can be disturbing to a significant section of the population. Moderate amnesia involves recurrent brief episodes of memory blanks not precipitated by stress, a few prolonged episodes of thirty minutes or more, or the occurrence of one or two brief blank spells in the course of a few hours. If the memory blanks occur often enough to make time seem discontinuous, they can cause distress. Moderate amnesia can be particularly disturbing to people whose occupational functioning is affected by it. A schoolteacher with a tendency to blank out briefly while she’s teaching class has to worry about what her students were doing during that lost time.

Robert, now a practicing engineer, almost flunked out of graduate school because of moderate dissociative amnesia and difficulty in concentrating during exams. When I first saw Robert, he told me, “I have an excellent memory, but my mind sometimes goes blank when I’m taking an exam and I can’t recall information I know by heart. I feel keyed up and tense and lightheaded, and the answers escape me.”

Robert’s SCID-D results showed that other than his moderate dissociative amnesia, his ratings for the other four symptoms were all mild and did not indicate the presence of a dissociative disorder. Though his moderate memory blanks caused distress and some dysfunction, they were related to his anxiety rather than to any history of trauma or abuse. Medication coupled with cognitive therapy and training in relaxation exercises proved to be the answer. Once Robert had tools for handling his anxiety, his amnesia during exams all but disappeared. Robert’s case illustrates how the SCID-D rules out—or in other instances, rules in—a dissociative disorder.

In severe amnesia induced by trauma or abuse, forgetting takes a more alarming turn. Vince, a former professional wrestler who went into business with his wife’s cousin after he retired, is a case in point. When the cousin got in trouble with the law for his shady business dealings and tried to blame them on Vince, the duplicity stirred up homicidal feelings of rage that Vince found unbearable. He collapsed, regressed into a childlike state at the age of forty-two, and woke up with Ho memory of his past at all except his three children and the family dog.

Vince had daily episodes of lost time—“trances,” he called them—during which “dark people,” shadowy figures of all sizes and shapes, accosted him. They held him down, stuck needles in him or tried to strangle him, and threatened to steal his soul. Their assaults impelled him to perform astonishing feats of athleticism that caused him pain, like doing five hundred sit-ups at a time or arching his back while he was standing on his head until he was standing on his neck.

Vince’s psychiatrist referred him to me for an evaluation, and I diagnosed him with DID. In treatment with his therapist, Vince began to recall the trauma that originally brought on his amnesia. During his childhood he was sexually abused by priests in a Catholic school—the “dark people” in his trances. The homicidal rage he felt toward his wife’s cousin set off a return of his dissociated rage during the abuse and accounted for his forgetting everyone in his past, including his wife. After five years in therapy, Vince is still working to recover his history.

Amnesia for traumatic memories is a case of memory interrupted. Traumatic memories are most likely “forgotten” because of faulty encoding or retrieving. A major mental process contributing to amnesia in dissociative disorders is known as state-dependent learning. According to this theory, information encoded in one mental state is most easily retrieved at a later time under that same state. If a person experiencing trauma dissociates into separate states of mind, different memories will become available to that person at different times. Data encoded in one state will not be available to a person who is in a different psychological state; it will only be available when the person returns to the same state he or she was in at the time when it was encoded. For example, Harris, a thirty-seven-year-old pharmacist who was sexually abused repeatedly throughout his childhood by an older cousin, developed a six-year-old alternate personality named Barney. Harris could not remember the abuse until an assault by an armed robber at the drugstore where he worked triggered Barney’s return.

State-dependent learning theory explains the severe amnesia that occurs in DID. Experiences encoded in a psychological state of abuse can chain together into a complex and consistent personality if the abuse is sufficiently traumatic and persistent. These particular alter personalities may not remember facts that other alters remember. While the memories of overwhelming pain and fear are outside the person’s conscious cognitive awareness, they live on in an alter personality and are still psychologically active and influential.

The “lost time” or memory “gaps” of someone with DID have preserved the person’s sanity but have swallowed up a large chunk of his personal identity and past. Vince’s history, for example, is like a badly edited film with too much of the story lost in the gaps. The future of someone with severe amnesia is compromised, too. The inability to integrate traumatic memories causes the person to fixate at the time of the trauma and impairs the integration of new experiences. When Barney resurfaced, Harris was unable to concentrate on his job as a pharmacist and fill prescriptions that were beyond the comprehension of a six-year-old child. For many people, traces of the painful memory tend to linger and intrude as flashbacks, obsessions, or reenactments of the trauma in self-mutilation or other self-destructive behavior, as in Vince’s arching his back to the point of physical injury.

Self-injury in all its forms, including accident-proneness or a tendency to be victimized again in abusive relationships, may actually constitute screen memories of abuse or symbolic memories that a person is using to keep explicit abuse memories out of consciousness. Repeatedly hurting oneself is a way of not having to remember the original hurt. Self-wounding may also be an unconscious repetition of past abuse in an attempt to make sense of a dim but haunting memory. The person is trying to knit the implicit remnant of the trauma memory into the fabric of a continuous mental narrative.

Some researchers have described cutting or burning one’s own flesh as a short-term device for relieving the self-hate, guilt, and anxiety associated with childhood abuse and trauma. They note that the behavior is cyclical in many people, consisting of a repetitive pattern of self-injury, calm, and gradual escalation of psychic tension leading to another episode of violence directed against the self.

The amnesia that many self-injurers have for their destructive behavior may be related to the return of memories from which they have disconnected. Since the emotional pain of the returning memories is overwhelming, the person enters a trancelike state in an effort to keep them blocked. Self-injurers often say that they “find themselves” with cuts, scratches, or burns on their bodies in the same way that they find themselves in strange places without knowing how they got there. Self-wounding is a reality testing for abuse that the person, on some level, knows happened but has split off from consciousness. Injuring oneself can bring “forgotten” memories of abuse into awareness in several ways. The wounds themselves can reinforce the reality of past abuse, long disavowed by dissociation and the persistent denials of family members who maintain that the abuse never happened or was an expression of love. The pain of self-injury can test reality by restoring the feeling of being alive. Self-wounding can also reenact past abusive events symbolically, recalling them behaviorally, and reinforce the person’s conviction that he or she was abused as a child. The fear of remembering what one was forbidden to remember may make amnesia a survival tactic once again.

Some examples of severe amnesia include:

at least one prolonged gap in memory that results in serious dysfunction

finding oneself in a strange place without knowing how one got there

inability to recall important personal information (address, telephone number, etc.)

inability to remember months or years of one’s adult life

forgetting of a learned talent or skill

experiencing of significant distress caused by memory problems

Precisely because amnesia is the negation of memory, people with severe amnesia may be unaware that something is missing from their recall; they may have amnesia for their amnesia. One woman with DID, who compares her amnesia to a broken TV, puts it this way: “There’s just a blank there. Nothing. You have no recollection of existing at all. It’s like turning on a TV, only the TV doesn’t work, and there’s just a blank screen.” She goes on, “What makes it more confusing is my sense that even what I remember doesn’t seem like I remember it. I’m not too connected to it. The memory is what I’ve been told is the memory. It’s like people saying, ‘Here, let’s look at a movie of your life, and we’ll help you fill in the blanks.’ You watch the movie and that’s your history there. You think it sort of looks like it, but you don’t really remember.”

Inventing information as a “cover” for a memory gap—known as confabulation—is a strategy that many people with chronic amnesia depend upon to maintain relationships, hold jobs, or stay in school. They often resort to confabulation when they sense that honest admissions of their amnesia will undermine important relationships. Some find that self-employment is the only answer to the disastrous impact of chronic memory gaps on a job, but the gaps still get in the way. “I decided to become my own boss after my excuses weren’t covering it anymore,” says Jackie, a forty-three-year-old free-lance artist, of her severe amnesia related to DID. “The only problem with that is, you do have clients who want so much done by such and such a time, and lost time can slow me down. I don’t show up for appointments or they can’t reach me, that kind of thing. I’ve lost a few dozen accounts because of it. But I can’t be fired, so I’m lucky.”

People often compensate for having a frighteningly unreliable memory by taking notes, keeping diaries, or enlisting friends and relatives to help them retrieve forgotten events or details. Openly admitting to memory problems in our “information age” can put a person on the wrong end of an uneven playing field professionally and otherwise. To get assistance from others and still conceal their plight, some people with serious amnesia demonstrate considerable ingenuity. Says one: “I’m pretty good at faking it. If I don’t recognize somebody I think I should know or can’t relate to what they’re talking about, I just sort of keep my mouth shut and hope they’ll say enough about themselves or the topic that something will click in.”

Amnesia frequently involves a misperception of elapsed time. Time passes rapidly as a person goes “in and out” of time or is “transported” from the last moment of fully remembered consciousness to the present. Victoria, a forty-eight-year-old salesperson, recounts an episode of amnesia and fleeting time that is mild for most of us when we’re daydreaming or engrossed in work but is severe for her, because it happens to her several times a week: “All of a sudden I’ll find myself standing some place, maybe at the kitchen sink, and I think, ‘What time is it?’ I look at the clock, and then I go through a process of figuring out what time it was before I blanked out, what day it was. And then I start thinking, ‘What happened? Where did the time go?’”

This distorted sense of the passage of time can extend to seasons of the year. “I get the months mixed up,” says a thirty-year-old woman with severe amnesia. “I’m wearing a sleeveless outfit—it’s eighty degrees out!—and I think it’s January. I go into the mall to go shopping, walk by a sign that says, ‘Summer Sizzling Sale,’ and my reaction is, ‘They should take that sign down, they’ve made a mistake, they shouldn’t be advertising summer clothes in January. And then the message comes in, ‘No, it’s not January, dummy. It’s July.’”

Paradoxically, people with dissociative disorders have amnesia for much of their childhood but can have an enhanced memory (hypermnesia) for the abuse under certain circumstances. Flashbacks, causing the traumatic memories to resurface with a searing realism, can be excruciatingly detailed and usually occur during stressful periods in later life—military service, academic exams, job loss—or when a sensory “trigger” abruptly activates them. A trace element of a past traumatic experience can cause a person to react dramatically to a seemingly innocuous object without any conscious awareness of the symbolic connection between the two.

Donna, a twenty-five-year-old secretary, described herself during her SCID-D interview as being “paranoid” about handkerchiefs and “scared to death” to touch one. She couldn’t understand why until, in the process of being diagnosed with DID, she traced back over her history and suddenly stumbled upon a horrific hidden memory. “I guess I was four years old,” she said, “and a baby-sitter used to gag me with a handkerchief, shove it down my throat, and rape me. No wonder I’m afraid of them, you know?” She went on to say, “I’m afraid of libraries, places with high bookshelves, because that’s the room I was in. After a while you learn to remember things like that. I don’t want to remember them, but in order to help myself I know I have to.”

The time gaps that occur for people with a dissociative disorder are usually not really empty. In the most severe cases, as in DID, alter personalities typically emerge during these episodes, and the amnesia serves to separate one personality from the others. Some trauma survivors may reenact the abuse during lost time and awaken with self-inflicted wounds, having no awareness of their cause. Others may travel, sometimes arriving at a city in a different state with no recollection of how or why they are there, or commit violent crimes in a trance and not remember them afterward.

Self-destructive alter personalities may attempt to kill a person during a rime gap, and the dominant personality may regain consciousness in the hospital without any memory of taking an overdose of pills or jumping off a bridge. In the distorted logic of a DID trance, one alters wish to destroy the body that passively endured the original abuse is not always recognized by the person’s healthier personalities as wanting the irreversible destruction of all of them. The amnesia that once banished overwhelmingly painful experiences from consciousness and helped the person survive has turned into a deadly threat.

The following questionnaire will help you identify what symptoms of amnesia you are experiencing and whether they are mild (normal), moderate, or severe.

Steinberg Amnesia Questionnaire

Instructions: Please check one box for each item to indicate the greatest frequency with which each experience occurs. If the experience occurs only with the use of drugs or alcohol, check the last box on the right.

If you have had any of the above experiences, answer the following:

To Score Your Amnesia Questionnaire:

Assign a score of zero to the following items: Normal items: #1, 4, 7, 10, 13.

For all other items, assign a score ranging from 1 to 5 corresponding to the number on the top line above the box that you checked.

Now add up your score. Use the general guidelines below for undertanding your score.

OVERALL AMNESIA SCORE

| No Amnesia: | 10 |

| Mild Amnesia: | 11–20 |

| Moderate Amnesia: | 21–30 |

| Severe Amnesia: | 31–50 |

If your total score falls in the range of No to Mild Amnesia (10–20), this is within the normal range, unless you have experienced Items #6 or 15 recurrently. If you have experienced these items several times, we recommend that you be evaluated by a professional who is trained in the administration of the full SCID-D interview.

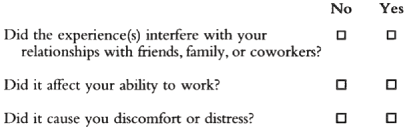

If your total score falls in the range of Moderate to Severe Amnesia (21–50), we recommend that you be evaluated by a professional who is trained in the administration of the full SCID-D interview. If your amnesia has interfered with your relationships with friends, family, or coworkers or has affected your ability to work or has caused you distress, it is particularly important that you obtain a professional consultation.

Should an experienced clinician find that you have a dissociative disorder, you have a treatable illness with a very good prognosis for recovery. Your illness is widely shared by others who coped with trauma by using the self-protective defense of dissociation. With proper treatment, in time you will begin to access memories and feelings that you have mentally disconnected from because they have been overwhelming. Eventually, as you grow strong enough to reconnect with your hidden memories and feelings and accept them as your own, your amnesia will be reduced and you will become a more integrated and psychologically healthy person.